OF MAHARAJ-JI’S LIFE much is unknown and much is conjecture. Dada said:

We do not know about Maharaj-ji’s education, or the forms of sadhana he had undergone, or what guru he had. We only know that before the ashrams at Kainchi and Vrindavan were built he was moving all the time. For how many years he had been moving like that, how many places he had visited, how many persons he had initiated or delivered from their miseries, nobody can say. We have knowledge only about particular places or times, a small fraction of his life. I have met most of his very closest and oldest devotees and all agree that we have known only a part of his life. Although the life of Babaji was quite a long one, it was only since the sixties that he stayed at the ashrams in Kainchi and Vrindavan or places like Nainital. Even at the ashrams Baba would be running away at the first opportunity. Also, he might be sitting with us, he might be talking with us, but he could also be roaming, moving about in another place or another world at the same time. There are so many cases of Babaji being seen in two or three different places at the same time. His body might be in meditation, but he might not be in it.1

He began to appear regularly around Nainital about 1947. Older people have recognized him as the guru of their grandfather, which would suggest that he had had another body.

It was not until almost a decade after Maharaj-ji had died or left his body that we Westerners who had been with him in India began to hear credible stories about his having a family. There had been an arranged marriage when Maharaj-ji was about twelve. He left home soon thereafter and did not return for nine or ten years. What was it like for his family, having a husband or father who was a saint and a guru to so many people?

Thinking back, it made sense that almost all his devotees were householders. Though deeply respected by the sadhus, yogis, and other saints, he was primarily a householder guru. In India holiness is not confined to celibate sadhus or renunciates.

His family has enriched our multifaceted picture of Maharaj-ji, especially for those of us who were with him. Now that we have children of our own and have become householders ourselves, we are in awe that he was able to keep both the spiritual and the family worlds going simultaneously.

Maharaj-ji was a master of what in India they call maya, the projection of illusion. Occasionally he let slip hints of this power when he said things like, “I hold the keys to the mind.” The separation of his family and spiritual lives was subtle. There was overlap between the two scenes, people seeing but not understanding. As the story has unfolded it became clear that these two strands of his life were indeed interwoven. A few devotees were aware of the family. And the family, although they were aware of Maharaj-ji’s spiritual life, didn’t make much of the guru business or comprehend the extent of his following.

Once Maharaj-ji returned home to his wife after being away. He put a handful of mustard seeds on his tongue. When he spit them out in his hand, they had all sprouted leaves. “See,” he said, “the spiritual business is coming along.”

Dharam Narayan, his second son, says he didn’t really come to know Maharaj-ji as a saint until after his death. Dharam Narayan just knew him as a loving father who was there when he needed him. Maharaj-ji always behaved with him like another member of the family. When Maharaj-ji occasionally took relatives from his home village traveling with him and they met the devotees, he would make sure they had plenty of the delicious food and special sweets that were always around. They were quite satisfied with the treats and didn’t pay much attention to the rest of what was going on, perhaps because Maharaj-ji was so casual about it.

Maharaj-ji was born Lakshmi Narayan Sharma on the eighth day after the new moon of the month of Margshirsh in about 1902 in his family’s mud home in the rural village of Akbarpur, some distance from Agra. His family were landowners of the Brahmin caste. At his birth the astrologers predicted he would have the blessings of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth.

His sons said that he was exceptional from birth: “He had no attachments. He was very generous and tried to help one and all, especially the underprivileged. He was very loving and affectionate.” They said love and affection overflowed in his presence, and that they have not been able to provide as much love and affection to their children as their father did to them.

Maharaj-ji’s father, Pandit Durga Prasad Sharma, was a learned man who was a great devotee of Hanuman, the monkey god, whom Maharaj-ji also worshiped. His father took him to Benares to learn Sanskrit when he was about six, and he spent a couple of years there before his mother, Kaushalya Devi, missed him so much that he was brought back home. She died of a sudden illness, possibly cholera, soon after, when he was about eight. His father remarried within a year to a young woman of eighteen or twenty. She and Maharaj-ji were in conflict from the start, probably because his own mother had so recently passed away and the new stepmother was trying to take the traditional reins of power as “mother” of the household.

When Maharaj-ji was around nine years old, one day he told his father that there would be robbers that night at their house. His father paid no heed and, sure enough, the robbers looted their house at gunpoint the same night.

When Maharaj-ji was twelve, his marriage was arranged. His bride, Ram Beti, was ten and, as was the custom, remained at her parents’ home until three or four months after the marriage, and then she came to live at her in-laws’ place in Akbarpur.

The friction between Maharaj-ji and the young stepmother continued, eventually culminating in an argument, after which Maharaj-ji was beaten by his father and locked in his room. Maharaj-ji escaped and left home. He was twelve or twelve and a half. He was not to return until 1924–25, nine or ten years later. Little is definitively known about those intervening years. The following sketch comes from Guru Datt Sharma, one of Maharaj-ji’s old devotees.

Maharaj-ji first went to Udaipur in Rajasthan and got a job as a guard in a temple. Soon he moved on toward Gujarat and reached Rajkot. He started staying with a mahant (head of a large monastic order of sadhus). He was known as Lakshman Das during this time. The mahant was very impressed by Maharaj-ji and declared him to be his successor, but his decision did not sit well with his other disciples. When the mahant passed away, Maharaj-ji left to avoid a controversy.

He reached the village of Babania near Morbi in Gujarat, where he stayed at the ashram of a woman saint, Rama Bai. Maharaj-ji used to sit in a lake (tal) near the ashram, meditating under the water for hours at a time. He became known as Talaya Baba (“Lake Baba”). After spending considerable time at Babania, he started roaming around India on foot, which he did for the next eight years or so. Dada collected some additional stories about the Talaya Baba period of Maharaj-ji’s sadhana:

Another clue came from Sri S. N. Sang, the principal of Birla College at Nainital and a great devotee of Babaji. . . . He narrated his first experience as a little school boy reading in a public school in the Punjab:

“The students used to have a camp for a few weeks in the mountains every year. We were in our camp in the Simla hills, collecting some flowers or running after butterflies, when we saw a man in a blanket passing by. We took no notice of him as there were so many persons coming and going. After a few minutes, a cowherd from a village in that area came running down shouting, ‘Such a great saint has passed by and you did not run after him!’

“The question that we hurled at him was why he himself had not followed the saint. He said he had gone to call Santia (his wife) and other people in the village. When the people started going up the hill, we joined them. After quite some distance, we all came back as there was no sign of the man in the blanket.

“The cowherd began to talk of his boyhood days, when he had known that man in the blanket as Talaya Baba, the baba who lives in a lake. The cowherd said that he and the other village boys used to bring their cows and goats for grazing. They used to carry their food with them for the noon meal, as they would not return before the evening. After reaching a nearby lake, they would tie their food in a cloth and hang it on the branches of a tree.

“A baba used to live in that lake (talao) and was known by the name of Talaya Baba. Whenever they came there, they would see him in the water. He was very kind, and everyone used to talk highly of him as a sadhu, but he used to tease them a great deal. When they came for their meal at noon, they would see that he had taken away their bag from the tree and had distributed the whole of it to the people coming to him, or to the animals. Then he would feed them in plenty with all kinds of delicious food—pure halwa, laddoo, kheer—they would never have imagined tasting so many sweets together. He would get the food by putting his hand on his head or from the lake in which he was sitting. He loved them much and used to talk to them when they were near him.

“This was long ago. They were just small boys then, but he remembered everything about Talaya Baba.”2

According to a baba who claimed to have accompanied him, sometime in the 1920s Maharaj-ji went on a yatra, or pilgrimage, following the banks of the sacred Narmada River to the ocean, then returning up the other bank to the starting point, Amarkantak. A sixteen-hundred-year-old baba was the organizer of the yatra, and at the end of it he was said to have bestowed his siddhis on Maharaj-ji.

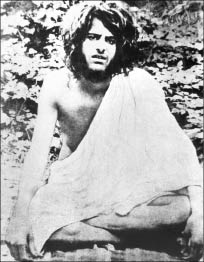

Maharaj-ji as young sadhu, Lakshman Das.

He is next heard of in the village of Neeb Karori. Maharaj-ji had an underground room or cave constructed where he did a lot of puja, yogic kriyas (or purifications), and havan (fire ceremony) and meditated. Someone used to leave a cup of milk at the mouth of the cave for Maharaj-ji every day. At one point the milk was not left for some days, and Maharaj-ji began to berate the murti of Hanuman that he worshiped for not providing him with sustenance.

Also from this time is the story of how Maharaj-ji became known as Baba Neeb Karori (or Neem Karoli Baba, as it later evolved). Since no one had given him any food for several days, hunger drove him to board a train for the nearest city. When the conductor discovered Maharaj-ji seated in the first-class coach without a ticket, he pulled the emergency brake and the train ground to a halt. Maharaj-ji was unceremoniously put off the train. The train had stopped near the village of Neeb Karori. Maharaj-ji sat down under the shade of a tree while the conductor blew his whistle to start the train.

The train didn’t move. It sat there for hours. Another engine was called in to push, to no avail. Finally some passengers suggested to the railroad officials that they coax the sadhu back on board. The officials were initially appalled by such superstition, but after many frustrating attempts to move the train, they decided to give it a try.

Passengers and railway officials approached Maharaj-ji, offering him food and sweets. They requested that he board the train and resume his journey. Before giving an answer, Maharaj-ji ate his fill. He said he would board the train on condition that the railway officials promised to have a station built for the village of Neeb Karori. At that time the villagers had to walk many miles to the nearest station. The officials promised to do whatever was in their power, and Maharaj-ji finally reboarded the train. As soon as he was back in his first-class seat, the train began to roll.

Maharaj-ji said that the officials kept their word. Soon afterward a train station was built. Maharaj-ji said he didn’t know why the train wouldn’t move. He certainly had done nothing to it, but it was on that day that his “business” really got started.

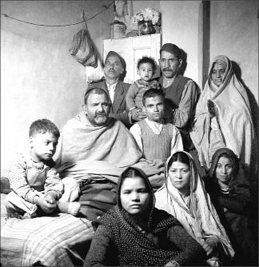

Maharaj-ji’s early days in Nainital.

During the years of Maharaj-ji’s absence, his young wife led an austere and difficult life. As word of her husband’s leaving home spread, the locals started teasing her. Some said that he had run away and would never come back or that he was dead. She had to listen to a lot of hurtful village gossip but could do nothing about it.

Ram Beti spent much of her time in worship. She would grind 250 grams (half a pound) of barley every day with the hand grinding stones of the time. With this flour she would make three chapatis. One she would offer to Shiva in the village temple, one she would give to a cow, and one she would eat herself. This is what she ate all those years Maharaj-ji was away. And she prayed to God continuously.

Someone from Maharaj-ji’s grandmother’s village saw a young man resembling Durga Prasad, Maharaj-ji’ father, on the banks of the Ganges in Farrukhabad. Because the man knew Durga Prasad’s son had run away from home, he informed the father, who went to Farrukhabad and discovered Maharaj-ji as he was going for his daily bath in the Ganges. He persuaded him to return home and take up his family responsibilities. Maharaj-ji had long hair like a sadhu, so he was taken for a haircut before he came home. This was in 1924–25.

When he first returned, Maharaj-ji stayed indoors most of the time. His powers were mostly hidden except for minor events, such as when his wife was unable to find something. Then he would tell someone to go behind the house, and the item would be found there.

Many babas and sadhus visited him at home, and guests were always welcomed and fed. His wife, though, who must have been more aware of his dual life than others, did not like hearing him addressed as “Baba” (an honorific for a holy man) and would get irritated with people who referred to him that way even after he left the body.

In general the saints and sadhus who visited were all respected and treated well. One named Keshavanand was given a warm welcome and treated in a manner befitting a saint. When another, known as Yogwale Baba, came to visit, chapatis were made and offered to him with vegetables. As he did not eat chapatis, he asked for paranthas (fried flatbreads), which were prepared. The baba sat eating them in front of the fire as it was very cold. A passing farmer who saw him eating the paranthas commented that he and others worked for the whole day and got dry chapatis—why was this baba, who did no work and refused to eat chapatis coated with ghee (butter), now enjoying paranthas?

The baba heard this and felt so bad he threw the paranthas in the fire and got up to leave. Maharaj-ji asked the baba to please stay. He immediately asked for preparation of puris (another variety of fried flatbread). These were offered to him by Maharaj-ji with great respect. He ate these and was so impressed by Maharaj-ji’s behavior that he fell at his feet. Later Maharaj-ji cited the maxim, “Bhojan, Bhajan, Khazana Nari / Ye Sub Purdah Adhikari,” meaning food, worship, wealth, and wife should all be kept private. Another saint who came to the village told a villager, one Shri Devi Ram, who was very close to Maharaj-ji, that Maharaj-ji was a mahatma, a great soul.

By all accounts Maharaj-ji was a loving and supportive husband and father who was present for all the important family events. His wife’s sister says, “He loved his wife very much and ensured that whatever she desired was made available to her immediately. He would look after her in a manner that most husbands would not. If she took some decision, he would stand by her if he felt that she was right, even if this meant going against the entire village.”

He did all she wanted except if he did not consider something right. A person came to the house asking Maharaj-ji’s wife for some money for his son’s release from jail. She refused, as this man was in the habit of asking for money on any excuse. Maharaj-ji was sitting upstairs and overheard the conversation and came down. The man said that his son was caught without a ticket on the train, and since he could not pay the fine, he was put in jail. Maharaj-ji gave him the required amount of money with tears in his own eyes. Later he told his wife of the feelings of a person whose son is put behind bars.

Three children were born in the ancestral home in Akbarpur, two sons, Aneg Singh in 1925 and Dharam Narayan in 1937, and a daughter, Girija, in 1945. Maharaj-ji paid particular attention to the education of his children, all of whom attended secondary schools and two of whom went to university. He did not differentiate between his sons and daughter, as did most families during that period, and insisted on the equal education for all the children. At times he personally escorted his daughter to school with an umbrella to protect her from the sun.

Maharaj-ji often taught his children with whatever was happening in the moment. Watching a family of birds in a tree he would say that as the mother bird feeds the baby birds, who fly away leaving their parents behind, we can learn detachment from the birds. He also used to relate stories from the Ramayana, particularly those about Sita and Anasuya.

He told stories and parables like that of a saint standing in the river who saw a scorpion floating by. He thought to save its life and picked it up from the water, but it stung him with its tail, causing immense pain, which he could not bear, so the scorpion fell back in the water as his hand recoiled. Again, the saint picked it up, and the same story repeated itself. Someone asked the saint why he kept doing this, when the creature was causing him so much pain. The saint said, “It is following its nature. When such a creature does not leave its nature, why should I leave mine?” Discomfort should not cause one to leave one’s essential nature.

Although the family had servants, Maharaj-ji treated them with respect. He didn’t consider any work insignificant. He would help the servant operate the chara machine used to chop the cow fodder because he felt it was a heavy job.

Wherever he was and whatever he was doing, his fingers were always moving, doing japa, repeating prayers. If anyone spoke to him he would say R![]() m R

m R![]() m, as if he had been silently chanting R

m, as if he had been silently chanting R![]() m R

m R![]() m all the time. He would lock himself in his room at Agra for days at a time, and no one dared disturb him except his wife.

m all the time. He would lock himself in his room at Agra for days at a time, and no one dared disturb him except his wife.

Maharaj-ji arranged all of his children’s marriages. At his daughter’s wedding, he warned his son to get an alternate source of light. Indeed, the power went out and lanterns were used. After Maharaj-ji performed the ritual giving of the bride to the groom, he left the proceedings early. Siddhi Ma said he was locked in his room at Kainchi most of that day.

Maharaj-ji said one can reach God while fulfilling his or her duties as a householder. He was generally home for all the important festivals, which he would celebrate as the biggest landowner of the village. The villagers would come to the house, and at two of the major festivals, Holi and Diwali, he distributed five-kilogram (ten-pound) bags of wheat (a relative luxury) to the poor. When Maharaj-ji was present, a lot of people would gather around him, including many sadhus. He ensured that all were looked after. The atmosphere around him was full of fun and joy.

People came to him with all sorts of problems. He said that serving people is service to God. When he met with the village elders, he treated those of every caste with respect and love without discrimination. He said one should always think of giving more than one gets. In those days, during the Holi festival when people throw colored water on each other to remember Krishna’s love play, people from the lower castes were not allowed to throw the color on people of higher caste. He was the first person in the village to break this restriction.

In many respects, Maharaj-ji was like any other father or elder of a family. The difference was that he was always very magnanimous in his approach and love flowed and poured from him. He always took special care in looking after his servants and the poor. Maharaj-ji loved to hear the Ramayana recited. Hearing the description of Sita alone in Lanka after she was kidnapped, tears would roll down his cheeks.

He started leaving home from Akbarpur for two or three days a month. As time passed, he would be gone for eight to ten days at a stretch, would come back and stay for a week, and then would be gone again. In 1962 the family moved to Agra, first renting, then purchasing a property. After his daughter’s wedding Maharaj-ji’s visits home to Agra and Akbarpur reduced drastically. When his wife had an attack of paralysis in 1972, however, he visited the family twice in Agra.

Dharam Narayan sometimes traveled with Maharaj-ji and visited him at the Vrindavan and Kainchi ashrams and at his Kumbha Mela camps in Allahabad or Haridwar. He would go basically to get spending money. Maharaj-ji gave him money, and he never bothered about anything else. If a spiritual thought crossed his mind or he heard of some miracle from devotees, Maharaj-ji would tell him that he was fooling everyone and Dharam Narayan didn’t inquire further. Siddhi Ma was very much aware of the family and would look after the family members whenever they visited him.

Maharaj-ji’s nephew was asked by his mother to go to the Vrindavan ashram to get some blankets. At the ashram he was mesmerized by the number of people and stood at a distance not knowing how to reach Maharaj-ji. Maharaj-ji shouted to him, inquiring about his mother and others. He told him to take the blankets his mother had sent him for. The nephew was surprised Maharaj-ji knew about the blankets without his uttering a word. Things like this happened constantly with family members but always seemed to get overlooked.

One year when his wife was not feeling well, Maharaj-ji moved the entire family to a rented house in Nainital for two months while he was in Kainchi. The family visited him from there.

On another occasion Maharaj-ji’s daughter, Girija, came down with typhoid while he was away. The attending doctor said he couldn’t help her, and the family was worried. Her maternal uncle went to Kainchi to tell Maharaj-ji. At first he looked worried, then he went into the Hanuman mandir, lit a lamp, and sat in the temple for some time. When he came out, he told the pujari to keep the lamp filled with ghee to keep it burning. Later, sitting with devotees, he said that this man was worried about his sick niece. He said nothing would happen to her and she would be all right. Girija recovered.

In essence, the family was content that he was a good husband, father, or relative, and no one bothered about anything else. From the first when Maharaj-ji came back home, the family knew there was something more to him. His wife used to question him a lot, but she never spoke and no one really knows what went on between them. Only Maharaj-ji knew how he kept the spiritual side and the family side of his life separate. This arrangement continued throughout his life, but both sides were happy, and nothing about the family surfaced in the large gathering of the devotees.

As the head of the landowning family in Akbarpur, Maharaj-ji was known and respected in the community. After India introduced democratic election of village officials, Maharaj-ji was elected headman of the village unopposed. He would sit under a neem tree on a raised platform, villagers would gather around, and he would resolve their problems. No siddhis were in evidence, though now some people say impossible things occurred and they did not realize it at the time.

Village life was not totally harmonious. Maharaj-ji wanted to get rid of the caste system, which was opposed by the higher caste people, including some of his own relatives. This created friction in the village. Later the headman post was reserved for a person from the lower castes. He ensured that a person named Bhoj Raj, or Bhoja, from a lower caste became headman despite the opposition.

He once asked his son Aneg Singh, “If I cut your finger, what color will your blood be?”

“Red,” Aneg Singh replied.

He then asked, “If the finger of the sweeper’s son is cut, what would the color be?”

“There would be no difference,” his son replied.

Maharaj-ji said, “If there is no difference, then why differentiate? Go and play with the sweeper’s son.”

This was at a time when the caste system was firmly in place, and he was telling his children to break away from it and ensure equality for all.

In the Body

When you go to see a guru or a saint in India, it’s traditional to offer fruit, flowers, or money. We often just brought Maharaj-ji apples or bananas. There was really nothing else you could give him. Maharaj-ji would take the fruits and throw them at people with astonishing accuracy. He really was a lot like a monkey. He had incredibly long arms.

Maharaj-ji’s body was extraordinary. Its form kept changing, depending on who was looking at it, when, and what work he had to do with that person. There were times when he seemed tiny and agile, other times when he seemed a mountainous bulk, like the time that Dada’s wife, Didi, tried to massage him and she couldn’t reach over his body, it was so huge. There were other times when he seemed diminutive, and you wanted to protect him. His height changed as well as the immense expanse of his belly. If you’ve seen pictures of Nityananda, you will recognize that same barrel-like quality, which is perhaps an effect of the shakti. The luminous buttery quality of his skin was extraordinary. It was so soft and creamy, and it smelled like a baby’s at times.

His eyes had long lashes, and they were usually half-closed. When you could see his eyes, they sometimes looked slightly crossed, as though one eye was seeing the world and the other was turned within. Only once when I was with him did he open his eyes fully and look directly into mine. The power of those eyes could take you into full samadhi. But to do that prematurely wouldn’t liberate anyone; it would just create another high, so he masked that power. People couldn’t bear that force, so he mostly kept his eyes half-closed behind those long lashes. The nail of his big toe was red as if painted with Mercurochrome. For the devotees it was like a lightbulb. But maybe he had an ingrown toenail.

He had incredibly flexible joints. He could join his hands behind his back and bring them up over his head to the front without ever disengaging his hands. He used to go to the children’s ward of the hospital in Nainital and entertain the children with yogic tricks. He would put his arms flat on the floor, turn a somersault without lifting his arms, and then go back the other way. He demonstrated this facility to a group of about ten devotees, clasping his hands behind his back and bringing them to the front without letting go.

A doctor from Bombay who had been the bone specialist for Kennedy and Nehru came, and Maharaj-ji showed him his right arm, which bent the wrong way and could do all kinds of weird things. Maharaj-ji looked terribly concerned and asked the doctor about it.

The surgeon said, “Well, clearly you broke it when you were a child, and it never healed. It stayed loose in this way.”

Maharaj-ji said, “Oh, isn’t that interesting. What about this one?” And he did the same thing with the other arm, which made the doctor seem like a total fool. Maharaj-ji had a way with doctors, chiding them about what they thought they knew.

When Maharaj-ji first came to Nainital, he would walk over the roofs and up and down little ladders into the homes that are stacked on top of one another in the Nainital bazaar, the center of town. K.K. took me up on the top floor of his home and showed me how Maharaj-ji had climbed across the roofs to where a young Siddhi Ma was making “burries” (lentil paste dried on the rooftops for later use in the winter), how she had pranamed (humbly greeted him) and the loving quality of his smile. Maharaj-ji went to the house of an old devotee, Sri Ram Sah. Siddhi Ma came and sang a bhajan so sweet that Maharaj-ji was in tears, and she was lost in the singing. It went, “Sumiran karley mere mana . . .” (“O my mind, remember . . .”). For a while after that Maharaj-ji would affectionately call Siddhi Ma “mere mana,” or “my mind,” recalling the bhajan.

In each home the women would prepare a meal, as it was a blessing for them to cook for a saint. Once Maharaj-ji started at 6 A.M. and kept going until 11 P.M. He ate some twenty full meals, huge meals, with puris and rice and all that. He just kept eating and eating and eating. At each home he’d get up and leave after ten or fifteen minutes. He was serving all those people incredibly by doing that. On the other hand, during his last few years in the body he ate very little, hardly anything.

Maharaj-ji would develop illnesses that came and went with astonishing rapidity. He might come down with a high fever and be wrapped in blankets, and then an hour later it would be completely gone. He might take on something that would cause somebody else to die, like a massive heart attack, and it would go right through him. He took on a lot of stuff for other people. Mostly this was hidden. Few people ever knew that he was taking on their karma.

K.K. once went to see Maharaj-ji at Kainchi and found him huddled by a charcoal brazier, wearing a wool cap, sweater, and socks (which he never wore), sniffling miserably. He said, “Oh, K.K., I am very sick!” Instead of being sympathetic, K.K., who has a certain bad-boy quality at times, said, “Maharaj-ji, why do you bother trying to fool fools like us?” His cousin M.L., who was with him, was a bit offended by his presumptuousness, but Maharaj-ji took off the socks and cap and stopped acting like he had a cold.

I suspect that much of what Maharaj-ji did was not for us to see. There were times, many times in the last few years, when he would seem to go away even though sitting there. I think he spent a great deal of time in formless samadhi in his last years, in the back room where we generally weren’t allowed to be with him. Once at Dada’s home, when the Ramayana was being read, they stopped the reading and moved him out, because he was going into samadhi.

The great tree of Sahaja is shining in the three worlds; everything being of the nature of sunya (emptiness), what will bind what? As water mixing with water makes no difference, so also, the jewel of the mind enters the sky in the oneness of emotion. Where there is no self, how can there be any nonself? What is uncreated from the beginning can have neither birth, nor death, nor any kind of existence. This is the nature of all—nothing goes or comes, there is neither existence nor nonexistence in sahaja.

—Bhusukupada3

The first few years I was with Maharaj-ji, he was always doing japa, saying R![]() m R

m R![]() m R

m R![]() m, on his fingers. By 1970 he wasn’t doing that so much. Sahaja samadhi, Maharaj-ji’s state, is sometimes described as the samadhi that comes automatically, spontaneously, when one is in form and not in form at the same time, one foot in the world and one in the void. I think of sahaja samadhi as a state where you go in and out with each breath, where the universe is re-created with each breath, as the Buddha described. Imagine that inside Maharaj-ji is not time as we know it, but it’s as if the mind moments have been spread out. It’s both huge and tiny, so that each mind moment, of which there are trillions in each blink of an eye, is a full universe that is created, then ceases to exist, and then comes back in. In the same way that Buddha could label each one, Maharaj-ji could live within each one. In those cessations of existence is God, beyond any concept of God. Even the concept of God is still a mind moment—but in between those mind moments is where God IS.

m, on his fingers. By 1970 he wasn’t doing that so much. Sahaja samadhi, Maharaj-ji’s state, is sometimes described as the samadhi that comes automatically, spontaneously, when one is in form and not in form at the same time, one foot in the world and one in the void. I think of sahaja samadhi as a state where you go in and out with each breath, where the universe is re-created with each breath, as the Buddha described. Imagine that inside Maharaj-ji is not time as we know it, but it’s as if the mind moments have been spread out. It’s both huge and tiny, so that each mind moment, of which there are trillions in each blink of an eye, is a full universe that is created, then ceases to exist, and then comes back in. In the same way that Buddha could label each one, Maharaj-ji could live within each one. In those cessations of existence is God, beyond any concept of God. Even the concept of God is still a mind moment—but in between those mind moments is where God IS.

At first when a person is going in and out of samadhi, those periods are very long. You enter into samadhi for periods of time on the physical plane, like for three days, and then you come out. Then maybe it’s in every night and out in the day. Finally it gets so that each moment is a full universe being created and destroyed. That ability to transcend time on this plane allows one to be both in God and in the world. It would seem to be at the same moment, although it’s actually sequential, but the unit of time is so tiny that for all intents and purposes it’s simultaneous. Maharaj-ji seemed totally relaxed, and yet there was always the tension of incredible energies and changes of levels. We saw so little of what he really was.

I think the greatest moment I ever had with Maharaj-ji was at sunset one day at Kainchi, when K.K., his cousin M.L., and I went out there. Ostensibly we were delivering some fragile things from Haldwani for Durga Puja at Kainchi. In the twilight sunset we just sat, and he was like Shiva. He lay down and started to snore, or what sounded like that, and he took me into states of ecstasy and bliss. I started to shake very violently and to go out and out, and he brought me down. He said, “He isn’t ready.” When we left, I turned back and watched him sitting there on his bench, just that living-murti quality of him.

Disappearing Act

In September of 1973 Maharaj-ji left the Kainchi ashram for the last time to go to Agra. As he got to the car leaving the ashram, his blanket slipped to the ground. A devotee picked it up for him, but he said, “Leave it. One shouldn’t be attached to anything.” It was folded and placed in the car. He traveled by the night train with only Ravi Khanna, a young devotee, attending to him. They picked up his second son, Dharam Narayan, in Agra, and stayed at the house of a devotee. Maharaj-ji complained of chest pain, and they saw a heart specialist, who examined him and said he was fine and just needed rest. They boarded the evening train returning to the hills, but got off soon in Mathura.

At the Mathura station Maharaj-ji went into convulsions, and they took him to the hospital in Vrindavan by taxi. The doctors there didn’t recognize him, but diagnosed his condition as a diabetic coma, gave him injections, and put an oxygen mask over his face. After a short time he took off the mask, said it was useless, and said, “Jaya Jagdish Hare (Hail to the Lord of the Universe)!” several times. His expression became very peaceful, and he breathed his last. He had died. As he said when he left Kainchi the day before, “Today I am released from Central Jail forever.” He was gone from that precious body we had all worshiped and loved, in which we had taken such delight.

Dada comments:

He wanted us to cut our attachment to his body. . . . The container, however precious or attractive, is not the substance we aim to acquire. We are told to set aside the container by taking hold of the contents. When we could not separate them, or failed to let go of the shell, he snatched it away himself and threw it off. The real Babaji is always with us and cannot be lost. Only the imitation one which stood before us creating illusions is gone.4

Though at the time it seemed like his lila ended, it has continued, in and out of many forms. His grace remains a constant invisible flow, like the solar wind, and the fragrance of his presence at the places of his lila can still be felt. Thinking of him is a channel for his love.