Well here we are, at the start of a new year already. It’s been a bumper crop of reviews this last year across the board so I would like to take this time to say a MASSIVE thank you to our plucky team of reviewers. It’s an honour to work with you all and your insights have steered us all well through 2019.

Well here we are, at the start of a new year already. It’s been a bumper crop of reviews this last year across the board so I would like to take this time to say a MASSIVE thank you to our plucky team of reviewers. It’s an honour to work with you all and your insights have steered us all well through 2019.

Here’s the first crop of 2020, and I look forward to sharing more with you.

—Sam Dolan, Reviews Editor

More reviews online at www.shorelineofinfinity.com/reviews

Beneath the World, A Sea

Beneath the World, A Sea

Chris Beckett

Corvus, 288 pages

Review by Joanna McLaughlin

Chris Beckett’s Beneath the World, A Sea follows the journey of a British police officer as he tries to uncover the truth behind the murders of a group of psychic human-like creatures. However, disembarking in the other-worldly Submundo Delta after a four-week river journey, Ben Ronson is confronted with an even greater mystery: what did he do during the days preceding his arrival in the Delta which he has lost all memory of? And does he truly want to find out?

While the premise of the novel suggests a move by the Arthur C. Clarke Award-winning author into the world of sci-fi crime fiction, the story can be better described as an exploration of the subconscious and the darkness that lurks within humanity. Indeed, Beneath the World, A Sea, has parallels to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness as Ben becomes increasingly unhinged during his time in the Delta and starts to question everything he thought he knew about himself.

As in his highly acclaimed Eden trilogy, with his new novel Beckett again proves himself to be particularly skilled at creating rich and evocative worlds and complex characters. Indeed, as a reader it was easy to share Ben’s feeling of being somewhat hypnotised by the beautiful but unsettling forests that lie within the Submundo Delta, and the enigmatic creatures that live within them.

For readers drawn to fast-paced, sci-fi thrillers this may not be the novel for you. However, for those looking for a thought-provoking novel that isn’t afraid to explore some uncomfortable questions about human nature Beneath the World, A Sea is well worth a read.

Rosewater: Redemption

Rosewater: Redemption

Tade Thompson

Orbit Books

Paperback, 374 pages

Review by Joe Gordon

The third and final part of Arthur C Clarke Award-winning Tade Thompson’s rather excellent Rosewater series arrives from Orbit, and it proves as engrossing as its predecessors. The first novel introduced us to the world of Rosewater, this unusual near-future Nigerian shanty-town that had grown into a city state, based around a vast alien dome, the power politics going on between locals, such as the city’s major, the Nigerian government, the secret police, the aliens and other groups, and the “sensitive” Kaaro and his psychic abilities, which are linked to the alien-created xenosphere. Book two, Insurrection, took us away from Kaaro’s point of view and expanded our experience of this world through the eyes of several other characters, less a direct sequel as viewing events from another angle, giving a much rounder picture of both characters and the history that has lead to this point.

Insurrection also expanded on the alien presence, far from the benign if mysterious visitors who do annual “healing” ceremonies (one of the things which has put the once shanty-town of Rosewater on the political map and made it important) and brought us the xenosphere, this is, in effect, a very slow-motion invasion of our world. It is one which has been going on behind the scenes for decades, centuries even, the base, Wormwood, with roots deep below the Earth. And now more of the aliens are coming from their distant world – or at least the digitally archived mental imprints of that now otherwise extinct species, downloaded into dead human bodies and re-animated in a process similar to the “healing” gifts given to human pilgrims and their injuries.

Jack Jacques, the mayor, has a tenuous alliance with the aliens, or at least a section of them (it appears there are cracks in the aliens and their plans and approaches, just as there are divisions between the different human groups), allowing them to take dead bodies for this resurrection project. Understandably many bereaved families are aghast as this use of the body of their deceased loved ones being used as a vehicle for an alien mind. The arrangement does buy Jacques some bargaining power with the belligerent Nigeria though, still smarting from losing Rosewater as an independent city-state – with the power of the alien behind him, they can’t move too openly against Jacques (not that is stops all sorts of backroom plans and schemes).

But this is a delicately balanced situation and not one that can be maintained for long. Nigeria and other powers are interested in what is going on and want to move more openly, laying plans to disrupt the city’s routine and destabilise it, Jacques knows also that he cannot rely on the protection of the alien, and even if he could, he understands that each new one that is brought here and downloaded into a former human body is another nail in the eventual coffin not just of Rosewater but for the human race on Earth. He’s buying time, but that’s all, and he may have less than he thinks – bad enough people are forced to surrender the freshly dead bodies of their loved ones, but what if the belief that the resurrected bodies are entirely blank slate until the alien mind is downloaded are false? What if there is even a partial imprint of the original human soul still trapped in that revived body, now shunted to the back of the mind as the alien takes control?

A lot of hard decisions are going to have to be made by different powers, all squabbling for their own angle and unwilling to face the fact that perhaps their angle is, in the long-run, meaningless if they don’t unite to try and prevent the eventual extinction of their own species and the take-over of our planet by another. Assuming, of course, it is even possible to stop something like this, which has been happening for so many years already, a slow-motion invasion that had established a beach-head long before humans even realise they were at war...

Thompson takes the multi-character angles from the second book and deploys them again here to great effect, giving us insights into the competing human and alien interests, from the ones who are tying to co-operate at some level to the ones who will stop at nothing to impose their own will, consequences be damned (not hard to see echoes of this in, for example, the current climate crisis in the real world and the groups that fight around that despite the dire consequences awaiting all groups regardless of their prestige or power or angle). The notion that the newly resurrected formerly human cadavers, now home to alien intelligences, could also still retain vestigial elements of the original person’s mind, their essence, trapped in there, is horrifying, and brings the idea of global invasion to a very personal, individual level, upping the horror element (it is also not hard to compare this to the often brutal colonial/imperial era of history in Africa).

With so much at stake none of the original characters are safe, and there is a feeling throughout of how precarious the lives of even characters we have come to love are, how easily they could die by the hand of the slow alien infestation or by the quicker hand of their own fellow humans still trying to score points for their own agendas. There will be a blood-toll here, and there is a sense of increasing desperation as some of the players start to fully realise the stakes they are playing for, even as they try to form new plans that they have no idea they can pull off. It really is all to play for here, and Thompson immerses us in the situation and in the character’s fates – it is a real gut-punch to see something bad happen to some – and keeps us guessing right to the end, how this will play out for both our individual characters and for the fate of humanity and the world.

The Girl in Red

The Girl in Red

Christina Henry

Titan books 368 pages

Review by: Lucy Powell

A fairytale, but not as you know it. An intriguing take on the classic Grimm fairytale “Little Red Riding Hood”, this new novel by Christina Henry is bloody and gripping in equal measure. Whilst the original fairytale is one strewn with darkness, with various tellings of it emphasising or muting the gore, Henry’s narrative delves even deeper, drawing out the potential for abject horror like poison from a grizzly wound, and shapes it into a post-apocalyptic disaster narrative.

We follow Red, the protagonist of the novel. Named “Cordelia” after her mother’s love of Shakespeare, she has a bright red hoodie and is on the way to her grandmother’s house. That much, as people at all familiar with the Red Riding Hood story, we already know. But what makes her portrayal refreshing is that Henry depicts her as a disabled person-of-colour, exploring the prejudice that both bring, even in a society in total collapse. Indeed, as Red walks, treading a fraught and frightening path through the woods and beyond, we are exposed to more of what has happened to bring her there through flashbacks. These nudge the narrative ever closer to the precipice between “real life” apocalypse horror, and sci-fi reminiscent of Alien or Stranger Things. A nasty scene early on in the novel where she guts a man with an axe promptly makes you aware of what kind of novel you are reading.

Middle America, indeed most of the USA as far as one can tell, is a bleak apocalyptic landscape, with its inhabitants ravaged by an illness for which there is no cure. But the shadow cast by this illness is a darker one, and not - as one would imagine - everything that it seems. Red, and those she travels with, find out more in a painstaking accumulation of tension that is only relieved in the last quarter or so of the novel. Even so, despite the relief, you are gripped with a curiosity about the wider world that, for all its world-building, Henry doesn’t quite manage to answer.

The “twist” of the novel is perhaps too jarring for a story that builds itself up to be a more realistic disaster apocalypse novel. Red is a character who constantly reminds herself of the realities of the danger, comparing her actions as separate to those of apocalyptic video games or novels, and so the direction Henry chooses to take with the twist proves to be not as satisfying. Whilst well-written, with an engaging protagonist, the novel seems to straddle two different genres that don’t mesh as perfectly as one might like.

Indeed, whilst the apocalyptic plot is familiar, as is the fairytale, I found myself looking for direct comparisons to draw between this narrative retelling and the original tale. The wolf-character, the stalking, vicious, and sometimes charismatic figure to Little Red Riding Hood, is hard to place. Is it the roving bands of militia? The bloodied footprints and dead bodies? The idea that other people in this story are “the wolf”, or the fact that this well-known threat is not immediately clear, is one which places a seed of doubt into an otherwise clean ending, reminding the reader that danger is never really far away. A clever, if albeit, weaker ending to a strong, vibrant plot, this novel is still worth reading for fans of “dark” fairy tales and apocalyptic works alike.

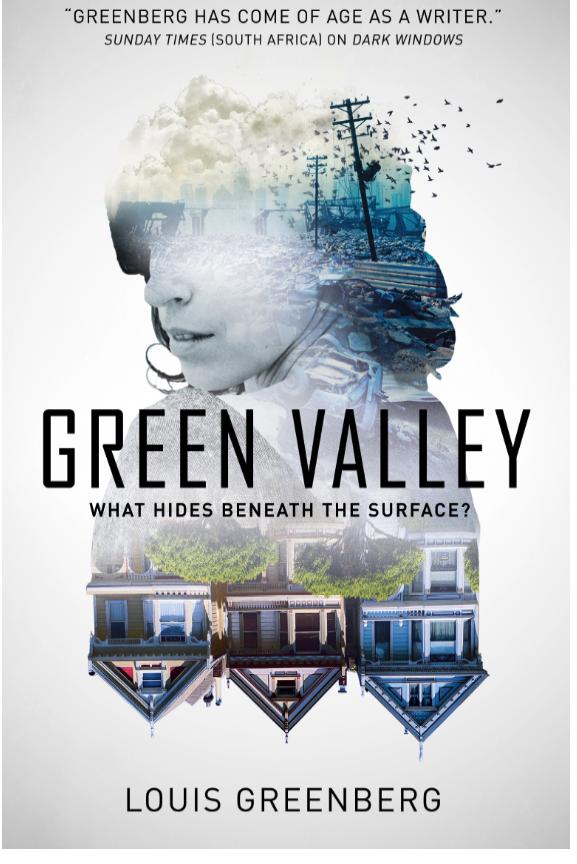

Green Valley

Green Valley

Louis Greenberg

Titan books 319 pages

Review by Samantha Dolan

If you came to the Cymera Festival in Edinburgh over the summer after purchasing your Shoreline merchandise, you might have noticed the VR rig in the corner. When I gave it a whirl, it was amazingly disorientating. And climbing up a mountain side and yet not climbing up at all left me feeling slightly nauseous. But I was so buzzed, I couldn’t stop thinking about that immersive world and when I could go back in for another try. When I heard about Green Valley, ‘a place where inhabitants had retreated into the virtual world full time’, I was intrigued.

The story centres around Lucie Sterling. Hers is a ‘post Green Valley’ world. Much like when the Berlin wall went up, a massive court case that exposed vast corporate corruption sealed the residents of Green Valley inside their virtual reality bunker and banned all technology for those living outside immediately. Lucie has a landline and uses keys and padlocks to secure her home. No smart phones or CCTV at all. Lucie has a sister, brother in law (David) and niece inside Green Valley but when her sister died, Lucie didn’t try and contact her niece, believing that Kira would be safe inside the only reality she’d ever known. But Lucie is a consultant for the police and when she finds out that three dead children could only have come from Green Valley, she realises that she could have been wrong all this time. In the memory of her sister, Lucie embarks on a journey to find out what, if anything, has happened to Kira.

There are several beautifully crafted scenes in which Greenberg explains how the virtual reality works. The reader is never allowed to forget that what Lucie is experiencing isn’t real, but we’re allowed just long enough for the juxtaposition between Green Valley and the bunker in which it ‘exists’ to be jarring. Technology-free Stanton isn’t a Utopia either. There is plenty of political intrigue and scheming within Lucie’s police department, that hamper her own investigation. It often feels like Lucie is the only one without an overt ulterior motive as all the antagonists are a heady mix of delusional and self-serving. Through the supporting cast of her partners, both work and romantic, we learn how the world collapsed and how people are creating new lives for themselves. But Fabian, her boyfriend, does sometimes feel like an exposition genie and is little heavy handed. Jordan is also, at times, a little cliched but they really are just there in supporting roles and the nuance of Lucie’s characterisation more than makes up for them.

The world building is detailed and delicate and feels very present day which heightens a lot of the tension but it would be overstating things to say that there are too many surprises in this novel. There is a moment where Lucie is forced by David’s new wife, to confront just how far from reality David has slipped and it’s gruesomely detailed but not ground-breaking. And I think that’s my only disappointment with Green Valley. It feels as though it’s just on the cusp of showing us a world we’ve never seen before but just stops short. Being a near future story has perhaps hamstrung the creativity here. But this is a well written, fast paced narrative that doesn’t shy away from the best and worst aspects of humanity. It’s definitely worth a read.