The Greater Sand Eel

What do they know of fishing who know only one fish and one way to fish for him?

Jack Hargreaves, Fishing for a Year (1951)

I depress the playback button on my phone for the fifth time in five minutes. It’s killing me to keep watching, but I’m desperate to find something, anything, positive amid this total horror show of a film.

‘That is one of the biggest sand eels I’ve ever seen in my life!’ it begins.

I’m shouting, partly out of excitement, and partly because the wind is whipping up so hard around the Dorset coast that it’s distorting the sound on the video.

In one hand I’m trying shakily to film with my mobile phone, while, in the other, I’m struggling to hold a British record fish. I don’t know what else to say. ‘It’s a whopper!’ I eventually stammer, sniffing back a runny nose and punching the ‘stop’ button.

I gently place my phone on my table and smash a cushion directly into my face. I’ve just made the biggest mistake of my entire fishing career, and, worse still, I know I’ve only got myself to blame.

There are few sensations in life that can match the angler’s almost immeasurable sense of loss when a big fish slips from their grasp. It is a poker-hot pain that continues to burn as bright in the memory as it did in the moment itself. Losing the sand eel record set me on a redemptive pathway that spanned the length and breadth of Britain. For over a year of my life I allowed the eel to completely take over, and, in the end, my angling would never be quite the same again. But that was all still to come. For now I was stuck in an angling purgatory, with bent hooks, broken dreams and that video for company. I pressed the playback button once more.

When I was a boy I used to revel in going around my grandparents’ home, a small bungalow that for me meant warm milky tea, chocolate sauce on ice cream, well-worn furniture and John Wilson’s Fishing Encyclopedia. My grandad would take the heavy hardback book in his thick fingers and, when I asked him, rest it on his enormous belly and thumb through the various sections. As far as I was concerned John Wilson was a god. He had a long-running series called Go Fishing that used to crop up for a few weeks a year on Anglia Television. It was on pretty late at night so I’d either try and stay up to watch it or get Mum to record it on VHS by laboriously punching the long code printed in the Radio Times into our tape player. Go Fishing spanned the period of time as a child when I was only ever allowed to catch tiny red-finned roach from the creek directly outside our house, roughly the ages of four to twelve, or ‘Argos Introduction to Fishing Kit’ through to ‘Kingfisher Coarse Supreme Kit’, if you prefer. The titles always began with John Wilson’s silhouette walking on an animated, but minuscule, planet Earth. He lumbered over the surface of our world as a giant, striding with remarkable ease from continent to continent, passing signs that simply read ‘fish’ and ‘more fish’. Pretty remarkable in itself for an adoring young super-fan from an insular village in the Cambridgeshire Fens, but the best bit about Go Fishing is that, despite what you might infer from the titles, Wilson rarely left Britain. His world was the chalk-fed River Wensum in Norfolk, the Royalty stretch of the River Avon, expansive gravel pits, beautiful Irish lochs and picture-postcard-perfect fish. Go Fishing’s gift was that it made catching fish, often of a specimen size, seem attainable. By catching well from his own backyard, Wilson made me, a novice angler, believe I too could catch well from mine.

Wilson placed equal value on all species of fish, a sort of ‘Martin Luther King’ of the fishing world, so it was to be expected that in John Wilson’s Fishing Encyclopedia no one species, method, bait or habitat was over-represented. From A to Z as much page space was dedicated to boilie baits as bread, carp as catapults, wire traces as wobbling dead baits. This was important because, to juvenile eyes, it presented the world of fishing not as a game to be completed, but as a near infinite set of variables where it was possible to utterly lose yourself in the discovery and mystery of the sport. Anything was plausible, because nothing was predictable.

In the Go Fishing era, any catch I deemed to be ‘highly unusual’ was hastily reported to Grandad with perhaps the same level of enthusiasm as an ecologist might have on discovering a new species after decades of fruitless toil. It mattered not that the fish species were, in reality, just slightly less than common, the days I caught my first zander, ruffe and bleak were moments to be celebrated from the highest platforms possible (from the narrow selection available to me from within my grandparents’ bungalow), climaxing with the highly ritualized inspection of the John Wilson Encyclopedia. The reason for this was three-fold: first of all, the book allowed me to glean the definitive facts on the ‘new’ species from the highest authority in the land (John Wilson), secondly it made me feel one step closer to my idol (also John Wilson), and, finally, it was a cast-iron guarantee that I could get the full and unadulterated attention of my grandad, a living breathing angling (demi-)god, of sorts.

I inherited the Wilson Encyclopedia when my grandad passed away two years ago. For a few weeks I couldn’t even bring myself to open it. It smelt of him and his bungalow; a precious bridge back into those memories before the body and mind of this once strong man gave way to life and death in a nursing home. It just didn’t feel right to read it without his permission and his bookstand stomach to open it from. It sat on my shelf untouched, the magic spilling from its pages.

Then the sand eel slithered into my life and changed everything.

I had never caught a sand eel before; let alone one within the ‘greater’ species definition. I strongly suspected it would be featured in the Encyclopedia – pretty much all the common species in the British Isles had made some sort of billing – so, with curiosity eventually getting the better of me, I decided this would be the appropriate time to finally peel open the pages of the formerly forbidden tome.

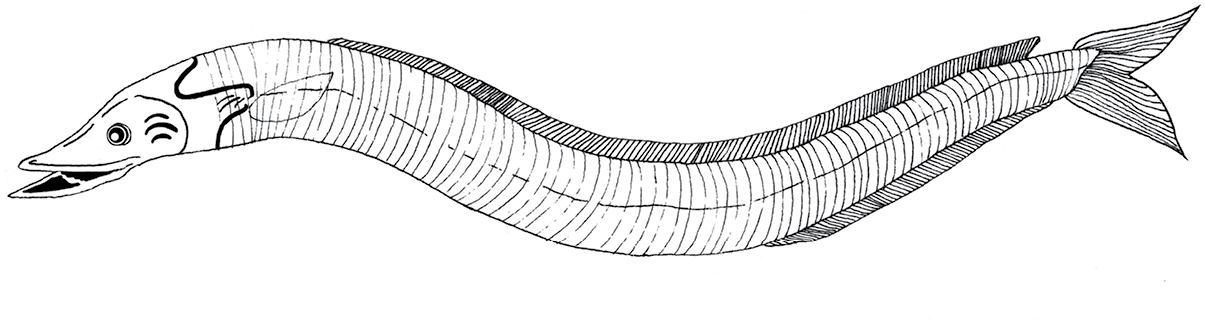

I found my fish wedged between the obscure Corbin’s sand eel and the squid-eating scad. With a supporting image resembling the scabbard of a dagger, the greater sand eel entry read: ‘the largest of the sand eel … The body is long, thin and smooth with a greeny-blueish back, blending down the sides into lower flanks and a belly of silvery white.’ Wilson goes on to say that you can only catch them on exceptionally small feathers armed with tiny hooks. That’s funny, I thought to myself. I had mine on the vulgarly named ‘Flying Condom’, a long hefty lure only really designed for the gaping mouth of the large sea bass or a sea-sprung salmon. The hooks on that lure are massive, thumbnail-sized and thick. Strange I managed to land that sand eel then. I supposed.

For a moment I just let that thought rest on top of my brain. A few more precious seconds of blissful ignorance after what had, up until that point, been a very enjoyable weekend. Inevitably, though, the thought drifted its way into the centre of my skull, fired up the synapses responsible for reasoned thought, and caused the horrifying implications of the Wilson suggested hook size, versus the ones I had used, versus the size of the fish I had managed to land, to dawn on me with force.

I recoiled from the book. What if the reason I landed that fish was that it was, in the modest world of the sand eel, an absolute monster?

The greater sand eel description had taken me onto a second page. I knew the layout of this book as well as if I’d written it myself. At the start of each species section Wilson always details the British record weight, which meant, just one page previously, the auspicious number was lying in wait for me. I felt a tremble somewhere deep within my bowels.

Just close the book, Will.

Close the book, put it back on the shelf and never open it again.

I turned the page back.

Eight and a half ounces. It was staring me right in the face, in black and white, directly below the drawing of the distinctly smug-looking greater sand eel.

Eight and a half ounces. That’s a pot of Marmite, a tin of beans, a four-pack of Mars bars, surely not a new British fish record?

I didn’t need to review the footage I shot that morning to know with certainty that the fish I had caught was in excess of 8.5oz, but I did it anyway, multiple times, and there it was: as bold as brass, wriggling along the length of almost my entire forearm. A fish clearly over 10oz, possibly even knocking on the door of one pound, a cast-iron miniature record breaker, and I had quite literally thrown it away.

To say I was fuming for the rest of the week would be to put it mildly.

Not only did I not speak for a good few days, but I could hardly even bring myself to look at the offending fishing tackle. I’d had my scales in my bag the whole time, the coastline had been packed with people, including my girlfriend, who had patiently waited for me at the top of the rocks, and I’d even had my camera with me. Getting that sand eel officially registered with the golden trifecta of witness, weight and photo, required by the British Record Fish Committee, would have taken less time than it took me to come up with my stupid little speech on that stupid bloody video. A video, I might add, which now only exists as little more than an everlasting record of my own unbelievable ignorance.

Let’s be honest, no one is going to be particularly rushing to break the doors down at the British Record Fish Committee to register a new shore-caught sand eel record; nor are the editors of the national angling press waiting, poised over their typewriters, for the sensational scoop of my ‘against the odds’ battle with sand eel destiny, but that is precisely the point: no one actually wants the greater sand eel rod-caught record, which means it was the perfect record for me to break.

In truth I am still something of an amateur fisherman. Sure, I know my way around several different styles and techniques, and have had more than my fair share of luck, but realistically that sand eel was absolutely my best chance of making it onto the list of official record breakers, and I had completely blown it.

During the golden years of the John Wilson Fishing Encyclopedia, back when I was twelve years old, I would fish only two waters: the Well Creek, outside my childhood home, and Popham’s Eau, a vast drain which I would venture to once a week with my grandad. I may have gone to the local school but this was where I truly received my education. More than just the places I caught my first fish, these twin rivers were where I learnt my watercraft and discovered the workings of the natural world, where I made my first real friends, and endured the rain and cold without running home to Mum. Very occasionally they were also the settings of the purest personal triumphs I will ever experience in my life. I would go on to catch much bigger fish from hundreds of different venues with far greater names than Popham’s or the Creek, and yet the memories of my time on those banks remains undiminished. I ask myself now, looking back, am I truly more knowledgeable as an angler now than I was then? In my childhood, thanks to the Encyclopedia, I knew every single British fish species, and its record weight, by heart.

How could I not have realized I had caught a new record then? The answer was obvious and it was staring me right in the face. On the wall of my study I had pinned two sheets of A4 paper. One is the optimistically titled ‘fishing targets’, and the other is a list of potential venues and tactics. The list includes king carp, crucian carp, eel, perch, pike, salmon and roach, with ample space for notes.

Many years ago the plan was to work my way through the entire list, breaking my lowly personal bests, and introducing myself to as many new species and varied environments as I possibly could. Just as John Wilson did, and, it pains me to say it, just as my grandad would have liked.

I look up at that list now and know I’ve badly let him down. The pages next to all the native species are barren, whereas the sections dealing with the introduced and very foreign king carp are absolutely crammed with information: Monument, Linear, Redmire, popped-up plastic corn; 4G squid; the Source, crab-mist, chod, braid and spod. The list goes on and on, years of accumulated information on a single species, from a single type of venue, that has completely suffocated my childhood knowledge of the wider piscatorial world; pushing king carp facts in one ear and everything else I’ve ever learnt about fish and fishing right out of the other.

That lost greater sand eel was a sign from above. I’d stopped caring about where I fished, as long as there were fish. For two decades straight, the places I fished were near identical commercial ponds and lakes filled to bursting point with artificially reared carp and brought to my net using much the same methods and baits. As a result, I failed to identify the record breaker in my hands and rightfully lost my chance. Now, with the rediscovery of the Encyclopedia, I have all the ancient wisdom I could possibly require on virtually every single species and fishing technique within the British Isles, and that sand eel which slipped between my fingers is the kick up the arse I fully deserved and desperately needed.

I prise the list off the wall – it’s been up there for a while, the Blu-tack has gone hard and takes a small flake of paint with it – and select the biggest, thickest black marker on my desk. Striking a meaningful cross through the entire king carp section instantly makes me feel better. ‘It’s catching, not fishing,’ Grandad always used to say every time I talked up my latest carp conquest at the local commercial fishery; I’d give him the withering teenage eye roll reserved for uncompromising adults, but it’s only now I realize he was bloody right all along. I scribble all over the freshly drawn cross for good measure and focus in on all the other names left on the list, taking delight in rolling my tongue over the names like I’m reading a fairy tale to a child. These are legendary fish, steeped in history, yet bullied to the periphery of most anglers’ imaginations by this nationwide king carp obsession. To find the native, truly wild populations of these fish I’m going to have to travel to the sorts of places that exist well beyond the public gaze. Spots where most wouldn’t think to cast a line: tangled underworlds, crumbling docks and urban rivers, the dwellings of the truly abandoned, where a unique kind of freedom survives distinct from the regentrified, reimagined and sanitized versions of wilderness that I’ve just wasted the last twenty years fishing in.

I spread a map of Britain out on the table and am immediately struck by just how well watered this nation really is. The rivers and lakes stretch right across this island like a giant central nervous system, easily dwarfing our roads and motorways through their sheer scale and abundance. Obviously not all these waterways will hold record breakers, and I wouldn’t get very far attempting to wet a line in every body of water in Britain, but I know there are definitely ways of shortening the odds in my favour before I set off.

A quick search on the internet finds me the British Record Fish Committee’s record-coarse-fish register, which helpfully includes all the places the fish were caught and by whom. That feels as good a place as any to start out, but I know I must avoid becoming completely hamstrung by someone else’s list. A lot of these venues will have seen serious angling pressure since they produced their record, and doubtless some of them will also be part of expensive and exclusive clubs that I just won’t be able to access. But records are there to be broken and fish die or move on elsewhere. If I’m going to give this a proper crack I need to look to offshoots of pre-established record-breaking waters, speak to local people and be prepared to take seriously the near-mythic stories of park lake monsters and river beasts. After all, just sticking to the beaten track was pretty much what got me into this mess in the first place.

I take a deep breath. It feels like I’m learning how to fish all over again. I know this is going to take patience and extraordinary amounts of luck, but the night before I attempt the first fish is utterly sleepless. I feel like I can actually sense the monsters of my imagination queuing up to be caught, pressing against the inside of my eyelids, willing me on to success.