The Striped Assassin

I am haunted by waters.

Norman Maclean, A River Runs Through It (1976)

Proper fishermen would never set up their rods before seeing the water they intend to fish, but I’m not a proper fisherman and have learnt the hard way that I make a much more proficient job of putting together my tackle in the dry confines of my kitchen than on the bankside. By the time I’ve made it out of the door and down to the river, lake or pond, I’m usually far too excited about the prospect of the first cast to concentrate on tying my knots properly, and thus set myself inexorably on the path to experiencing the devastating parting of fish from angler, right at the point of least resistance: my crap knots.

The line peels from the reel’s silver barrel with a series of soft clicks and glides over the wooden top of my chair. I plan to keep this set-up extremely straightforward as big perch hate complication.

I squeeze an extra-large shot of weight, the shape and dimension of a rabbit dropping but heavy and hard, on one end of a short, six-inch length of line. That’ll keep my bait pinned hard to the lake bottom. To the other end I attach a swivel, a tiny barrel of metal with two small rings at either end, which I then thread onto my main line. The swivel allows the weight to slide sweetly along the length of line without registering any resistance should a big perch pick up my bait. It slides down sweetly; free and smooth, right along the length of the line till it hits the rod’s tip with a satisfying ‘plink’.

Perfect. Zero resistance. The perch won’t even know it’s hooked.

My whole life has been one spent surrounded by water and my happiness can be accurately measured by my proximity to it.

I was born in the Cambridgeshire Fens; one of two, five minutes before my twin sister, Anna, with a little brother, Tom, coming along some seven years later. Ours was a house filled with nature, thanks, in no small part, to the unbridled enthusiasm of our dad.

He was a magical figure to me as a scabby-kneed under-five. I didn’t really understand why he was so often not around, the demands of his job as the local village doctor frequently taking him away from us for longer than we all would have liked, but when he was there he poured his love of wildlife deep into the souls of his children.

Through him I learnt to seek pleasure in bird-watching walks in fenland waterscapes, or to train my eye onto the very tiniest of life forms, dissecting the underside of a carefully lifted log with forensic precision, in the hope of snaring one of the worms or pungent ground beetles that lived there.

He seemingly hadn’t inherited his father’s passion for angling, but in those early days he armed me with the essential patience and respect I would require to winkle out fish later in life.

My earliest memories are really just a haphazard collection of senses and emotions, but they all revolve around the natural world brought to my palms by Dad. First there was Norman, the Airedale terrier. Unwisely purchased just before Mum gave birth to us twins, he was a mix of hyperactive, ginger, hard wire wool and smelly wet tongue. Next was the mustiness of Dad’s vast butterfly collection, which had a sort of pungent, slightly oppressive, perfume-like smell that you might also find around the embalmed corpses in the British Museum. I have always associated that scent with the dark wood and glass that contained his treasures and, if allowed, I would open the drawers with real care and reverence. The residents of these cases were frozen in time. Ossified and rigid, captured and sacrificed, all in the name of science. Even if I removed the glass they were trapped behind they could never grow or float through the sky again. I knew that this was not a time to smile or make jokes as the creatures that lived in there were actually just dead.

Living animals in the house, apart from Norman and the occasional woodlouse that made it (very) briefly into the room I shared with Anna, were accommodated in the circular conservatory at the back of our home. This pleasure dome for captive wildlife all but guaranteed victory for the Millard twins on the Upwell County Primary School ‘show and tell’ table, something that was of extreme importance to me at that time; plus, it was perfectly placed at the foot of the garden, providing a thrilling portal between the familial and the feral.

Dad would often hatch foreign moths and butterflies in the warmth of the glass house, the death’s-head hawkmoths were easily my favourites. With their human skull patterns emblazoned on their thoraxes like bikers’ tattoos, I thought they had to be just about the coolest insect that ever lived, but it was in the careful handling of the giant Atlas moths that I learnt the value of being gentle with any living creatures. Even the smallest brush of a wingtip could leave a guilty trace of their dust on my fingers. It was the Atlas depositing tiny scales from their bodies and would dull their colour instantly. Even today, despite having pulled a fish through the water with a hook in its mouth, I chastise myself at the loss of a single scale as a result of any rough handling on the bank.

Dad taught me that it was sometimes okay to catch animals to study and admire, but, as he aged, his focus became less on capture and more on the observation. Photos replaced traps, his butterfly collection waned, and the insect population of the conservatory began to dwindle.

I guess that was where Dad and I differed in our approach to nature. For him it was enough to simply observe and understand from afar; for me, it was necessary to get as close as possible, and, ideally, hold the creature in my hands. It wasn’t a case of wanting mastery over the natural world – I wasn’t one of those cruel kids who would pick the legs off a daddy-long-legs for a laugh. I just seemed to get infinitely more from something I could actually hold, touch and, years later, catch then release.

One day, a new resident was installed in the conservatory fish tank. It was to be my first close encounter with a fish, and, my goodness, what a fish it was.

In researching for this book I have since learnt from Dad that the brook lamprey was actually with us for only a single night, caught in a willow wicker-work trap by an eel-catcher from our local creek and given to Dad because he was ‘into that sort of thing’. Yet I remember it like it was there for the entirety of my early childhood. For the under-fives, time lengthens and memories compress in unusual ways; that one-night stand with the lamprey made a massive impression.

According to the Wilson Encyclopedia the brook lamprey ‘rarely exceeds an adult length of 10 inches’, which is quite extraordinary as I was fairly convinced our specimen was the size and girth of a Burmese python. Wilson goes on to note that its ‘sucker-like mouth is used only for adhering to the undersides of stones’. Now, not that I wish to accuse a fisherman, of all people, of understating the facts somewhat, but at no point does Wilson highlight that this fish has to be one of the most bizarre-looking creatures in Britain, if not the planet Earth. Not only does it have no fewer than seven separate gills, running in a hole-punch-like line right down its body, but he also neglects to mention that its ‘sucker-like mouth’ is, in fact, a horrific circular suction pad filled with a truly nightmarish series of studded teeth.

For hours my sister and I stared at the curious fish in the tank; utterly transfixed. It didn’t seem to move much, preferring instead to spend its time stuck hard to the glass side of the fish tank. Perfect for me, though, as it afforded a close-up view of those extraordinary mouthparts for the brief period it was in our custody.

It was a highly unusual capture anyway. The brook lamprey is most often found in fast-running streams where it can happily breed on gravel deposits; in the turgid murky waters of the river outside my home it seemed an absolute imposter. That thought delighted me. Out there, beneath a brown theatre curtain of surface water, was a subaquan wonderland just waiting to be discovered: a place where real monsters lived and died, well away from the gaze of us land-dwelling, air-breathing mortals, yet it could be accessed briefly; if, and only if, you learnt how.

Dad took its picture, and the next day the lamprey was gone, returned to live out its unlikely, and doubtless quite lonely, life in the water running around our tiny village, and I was left to advance an obsession with what else might be caught from water.

In the ironed-out landscape of the Fens, water is absolutely everywhere and, as a result, I grew up an extremely happy little boy.

I needed guidance to access water for the first time of course, but Mum and Dad were never afraid to let me go near the water’s edge, with supervision initially, and later on my own.

I was lucky; lucky to have so much space to play in safely, but also lucky to have parents that understood the importance of allowing me to discover the outdoors and water for myself, by myself.

I’m at that stage of life now where all my friends are starting to have children of their own. It only takes moments in the company of a young person to realize that a fear of water is inherited and not innate. Last week, my two-year-old niece Edie was utterly mesmerized by my fish tank, desperate to dip a net in and learn the names of the fish; her wild eyes reflected in the glass sides as her mind hungrily consumed every new scale pattern and plastic leaf. Eventually she reached out her tiny hand and ran it along the tank corner and on into the wet within, learning, in that moment, the curious interplay between glass and water.

It’s fascinating to see, and I believe a vitally important part of development, yet most children these days are absolutely forbidden from taking any interest in water outside of the bathtub. How many times have you seen anxious parents grasping the hands of their children in horror as they approach the six inches of ‘deep’ water at the edge of the municipal park pond? Or adolescents getting terribly scolded for daring to place their fingers in a perfectly clean town centre stream? Eventually these irrationalities rub off and those children grow up with their own unnatural fear of wild water, and, somewhat inevitably, so do their offspring in turn.

Not all of those fears are completely without foundation. Tragically, the last decade has seen an average of 390 people per year drown in accidents in British inland waters; but look a little closer into the figures and you will see that doesn’t automatically mean that the water outside our home is inherently dangerous for young children.

Of those 390 the single largest category is males aged between their mid-teens and mid-twenties. Many instances are alcohol-related, most are avoidable: young people looking to prove themselves by swimming distances beyond their ability or fatal injuries caused by diving head first into surprisingly shallow water, or water that is dangerously fast, or too deep, or just shockingly cold. Instead of teaching young people to be aware of the risks and guiding them towards safer areas to play and wild-swim from an early age, the prevailing attitude seems to favour putting up warning signs, locking gates, building barriers and telling our children that natural water should not be entered under any circumstances, and especially not for your entertainment. Let’s face it: since when have any of those sorts of measures stopped your average young person hell-bent on besting his or her peers?

Year on year more obstacles to accessing our waters appear, and year on year the number of deaths stays more or less the same. Surely it is better to invest in teaching our children how to manage risk in water, and thereby avoid tragedy, than to let them stay indoors, where they live their lives vicariously through the internet and television?

There are reams and reams of studies proving the physical and mental health benefits of just being near water. More than that though – perhaps most importantly in fact – our fresh water desperately needs our attention.

Thanks to myopic human development, rampant pollution and climate change, freshwater habitats are now easily the most endangered environments on earth. In the last half-century the doubling of freshwater withdrawals for our own ends has caused 50 per cent of wetlands to vanish altogether, and fewer than seventy of the planet’s 177 longest rivers remain free of manmade commercial obstructions.

For freshwater fish, the news is even worse: one third of all species are threatened with extinction today, compared to 21 per cent of mammals and 12 per cent of birds. Yet if you cast a speculative eye on the adverts for all the major wildlife charities, you’d be forgiven for thinking our fishy friends are doing just fine; but if you are beginning to think it’s bad for them, you should check how awfully the amphibians and freshwater invertebrates are faring.

You may well like to believe it is in the developing world, in the sorts of places where populations are dependent on harvesting freshwater fish just to survive, that the results would be at their worst, but looking at Europe in isolation we see that the number of fish species facing extinction is nudging up to a shameful 40 per cent, and, according to the European Environment Agency, half of our rivers and lakes are polluted. Things aren’t much better in the United States either. Over the pond, the rate of fish extinction is now over 800 times faster than in the fossil record.

We are marching to the brink of a worldwide environmental disaster, and yet there is little more than a whimper of protest.

Of course we should all be up in arms, but how can you reasonably expect people to care about saving an environment that they are preconditioned to believe is irrelevant and dirty at best, or a dangerous menace at worst?

Every garden should have a pond. Ours was oval-shaped and about ten feet wide. At one end there was a neat little shallow area that allowed amphibians to come and go as they pleased and provided a safe nursery area for frogs and toads to spawn. It dropped to a depth of no more than a couple of feet from that shallow point and was stepped in at the edges so Mum and Dad could submerge baskets filled with aquatic plants and water lilies. In the summer the centre was near solid with Canadian pondweed, an invasive species that shrouded the pond’s surface with its green pipe-cleaner-like tendrils while providing oxygen as well as shelter to the host of invertebrates that lived within its bulk.

It was here I learnt how to hunt frogs, the first living thing I ever knowingly caught from water (the first living thing I caught unknowingly from water was a ‘miller’s thumb’, a three-inch-long micro-fish with a fat head and rounded tail that slipped inside my wellies when I fell into a stream in Yorkshire).

I was appalling at first. My ham-pink hands slapped the water’s surface like a drummer’s cymbal each time a frog dared to lift its head above the weed. The first rule I learnt then was to be patient and observe.

Soon enough I realized the frogs in the centre of the pond were never to be caught: they always had a couple of feet of water below them to sink down into, whereas I was aiming at only about half an inch of a frog’s head. To go for them in the middle was to disturb the whole pond for hours; the best bet was to wait for them to approach the edge, as the shallower water would significantly narrow the frog’s options for escape.

At first I would leap up and try to grab them the moment they came within reach, thus breaking the second rule: keep your profile off the horizon.

Down the frogs would plop en masse. It took me some time to realize that if I stood up, particularly with the sun behind me, the frogs would see my silhouette ten times out of ten and scarper before I could get anything like close enough to catch one. So I took to lying on the grass, obscuring myself with the pond’s bordering plants and watching like a tiny blond otter.

It was to be the beginning of a lifelong fixation with peering into water. As a child I couldn’t really make out the difference between a natural or a man-made habitat, but that hardly mattered as nor could the wildlife. I remember being amazed to discover that if you left rainwater to puddle in a bucket it would quickly become inhabited all by itself. Usually this just meant a colony of tiny waterbeetles or millions of species of swirling zooplankton, but sometimes I would find mosquito larvae jerking in the water like a tiny hairy finger trapped in a door, and, in bigger, older, water traps, like the defunct water butts or abandoned cattle troughs that got left around farms, it was possible to find small fish, thick black leeches, and, very occasionally, even an eel.

Not all ponds are the same but the best times to observe, and afterwards to fish, were early mornings and later in the afternoon. In most ponds at such times, a background hum of life builds in a crescendo like an orchestra tuning up before the performance begins. This was when our pond was at its most magical. Bright damsels and acrobatic dragonflies, the assassins of the sky, hunted on the wing above my head as fearsome diving beetles plundered the unfortunate larvae living below. I had a soft spot for the alien-faced waterboatmen: they seemed like gentle souls who didn’t need to attack anything in the pond, but the pond skaters were always the most impressive. With their fine displays of nimble skills on implausibly long legs, these thumbnail-sized insects comfortably outmanoeuvred the birds and beasts that wanted to eat them by propelling themselves along the pond’s meniscus at incredible speed. Dad taught me that everything which lived in the pond relied on the health of its tiniest living organisms, and if I scooped the pond water into my hands and viewed it with my pale palms as a backdrop I could just make out what he was talking about. Hundreds of tiny haphazard dots made up a dense concentration of zooplankton: water fleas, daphnia and the water worms that held this whole environment together. Their presence was why he didn’t want to stock our pond with ornamental goldfish or koi carp. Pet fish would soon eat all these miniature friends, as well as the beetle larvae and the frog’s tadpoles, until, eventually, the entire system in the pond would stop being able to support itself. Then we would have to buy food to feed the pet fish, food which, I later learnt, was largely made from wild-caught baby sea fish, fish oils and even the krill that provided the foundation of the ocean ecosystem. It all seemed a bit crazy really: damaging one ecosystem to artificially prop up another, so we stuck with the wildlife pond.

If I was really quiet I might be able to see the garden birds – the song thrushes, blackbirds and sparrows – bathing in the shallow end of the pond. They would do this all year round, even in the middle of winter when the pond had a skin of ice and I could scarcely stand to put my hands in the water, but it seemed to happen most often towards the end of a long hot day. They would shake themselves vigorously afterwards, puffing out their feathers and finery as if they had been placed in front of my mum’s hair drier and towelled down. As darkness fell, the pipistrelle bats with their coats coloured like old bricks, their dark ears, faces and wings, would funnel down flying insects by the thousand. I knew I would soon have to go back into the house for tea when that performance began, but not before I checked my surroundings for a repeat appearance from my most exciting discovery of all time: a small shrew that once crawled along the pond’s bank and right along my side as I lay there. It sniffed the air with its comically conical nose and screwed up its tiny eyes in disgust. It knew something was up, but I don’t believe it ever realized I was there or what I was, before it shuffled its way back into the undergrowth.

The frogs had a curious habit. They would actively hunt and, to my juvenile mind, play in the deeper water, but they tended to come to a standstill when they were submerged in the shallows right in the gaps between the planting baskets. They felt safe there, I guessed, and with that I had cracked my third rule: find the sanctuaries and exploit the routine.

Soon I had my first definite touch of slimy flesh; next I briefly clasped a leg and then, finally, after a summer of study, I proudly held my first frog. I only had it in my hands long enough to splurt out the ‘M’ of ‘Mum’, before it released its stripy legs from my clutches and powered its way back into the pond, but it was, in my mind, a massive accomplishment.

I would tell everyone in the family several times of my heroism, establishing a lifelong fourth and final rule: always amplify any special capture, especially if there was no witness.

Finally, with no one else in the house left to tell, and my sister getting visibly irritated by my boorish antics, I made my concluding performance to my grandparents.

‘Impressive, son,’ Grandad remarked at the curtain call. Lifting an enquiring white eyebrow from behind his large, wire-framed glasses, he casually dropped an absolute thunderbolt into my life:

‘So what would you say to trying to catch a fish?’

A spark flickered into life; somewhere well behind my out-and-proud bellybutton and the small of my back: a truly great journey was about to begin.

I was almost five years old when I caught my first fish but I can’t tell you what it looked like. I was so excited by the prospect of catching and holding a real live fish that when my float eventually slid under the water, I struck so hard that I projected my catch directly out of the river, over my head, and deep into a field filled with sugar beet.

‘A little too hard perhaps, Will,’ said Grandad after a short spell of mutual silence.

He took the rod, freshly baited the hook with a couple of maggots, and re-cast into the middle of the Creek.

Technique wasn’t all that important in those seminal days. With Grandad it was all about experiencing the first fish on the bank, by whatever means possible, and enjoying time spent in each other’s company. That meant size was an irrelevance also. Our best bet, clearly, was with the vast shoals of roach that teemed within the Well Creek right opposite the house. They never seemed to grow beyond a few inches in length, but that didn’t mean they were foolish – far from it in fact.

With the float now bobbing happily in the centre of the Creek once more, I was passed back the rod. It was my first, a bright-red two-piece number with a smooth plastic handle and reel loaded with light monofilament line and I loved it more than anything else I have ever owned.

‘I’m just going to feed a few maggots to get them interested,’ said Grandad, selecting a pinch of the wriggliest bait tin residents and flicking them around the float with extraordinary accuracy. The float bobbed. ‘It’s another bite!’ I screamed, standing up, blowing our cover, and forgetting to strike. Grandad pulled me back into the seated position via the elasticated waistband of my bright-red shorts.

‘You’ve got to stay calm, Will,’ he implored in hushed tones, his eyes sparkling with suppressed laughter tears.

I refocused, pleading with the float and river to give me just one more chance. A couple more maggots flew out and then, finally, mercifully, it happened.

In the photo of that first fish, I am sat next to Grandad with a look of utter disbelief plastered across my face; my eyes are as wide as they could possibly be, gripping a length of line with what can only be described as ‘a miracle’ on the end of my hook.

Incredibly, given how many roach were in the Creek, my trap had worked its way into the mouth of a small skimmer bream. Like the roach, the skimmer appears to be a silverfish but it is, in fact, the juvenile form of the darker and much larger common bream. It differs from the roach in its elongated, slate-grey anal fin on the underside and its generally much flatter, wider appearance; hence its ‘skimmer’ name, in homage to a skimming stone.

To be honest, it could have been any fish of any species ever; my reaction would have been just the same. In that moment I was the king; the master and commander of the river; the man who had unlocked the secrets of the deep and tamed the great beasts that lay within. It mattered not that this was, in reality, an extremely small specimen either; in that brief moment I had been handed the keys to a lifetime of pleasure and study, and in Grandad I had a more than willing teacher.

The five years I then took to reach the age of adolescence revolved around fishing and an endless supply of fishy stories and patient tuition from Grandad. The pond, the conservatory of animals, my family and, later, school all dissolved into the background. I had a new magic man now, capable of conjuring the most almighty tricks with a dainty flick of his thick wrist.

We float-fished for the Creek’s roach at any opportunity. He couldn’t say no: I was irrepressible. He would rock up to ours usually on a good sunny day as Grandad really hated being cold, even though he did always like to claim: ‘There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothes choices.’ He would be wearing a floppy sunhat, and a T-shirt usually several times too small for his enormous stomach, and would often have a large pork pie secreted somewhere on his person, wrapped within a capacious handkerchief and brought out well away from the interfering eyes of my grandma.

I had the rod and reel of course, a couple of cheap floats, and a handful of hooks and weights he had given to me himself, but he would always ask: ‘Got all your stuff then, Will?’ as if my collection of tackle were vastly larger, and not, in fact, comfortably able to fit in his top pocket.

Grandad was both a thrifty man and extremely industrious. His fishing gear was as ancient as it was immaculate and his favourite floats were all handmade from drinking straws. ‘McDonald’s ones are the best,’ he often claimed, usually before adding: ‘it’s the only time you’ll see me in that bloody place.’ Repetition and consistency are a key component of any good angler, as well as any good grandparent.

The session would begin with my taking ten times longer than him to prepare my rudimentary tackle. I would first thread a small orange-tipped float onto the line by a tiny hole at one of its ends, and then secure its tip with a small rubber float sleeve, a finely cut piece of tubing that fixed the float to the line. Next I would carefully tie on a hook from Grandad and pinch a small line of lead shots intended to cock the float till just its top half-inch would show above the water. Finally, I was ready for bait. I would take an age to decide which two of the tens of thousands of maggots would be skewered onto my hook, usually drop a couple of hundred on the floor by accident, and then spear the grubs through the wrong end and have to start all over again.

When I was eventually ready to make a cast I would either overdo it and chuck the whole lot straight into a tree, or I would forget to release the line on the reel and tangle my float approximately one million times around the rod tip. Both eventualities took time to fix, and would nearly always result in me having to start the whole process again from scratch.

Grandad would never fish on through my dramas, but he wouldn’t just sort it out for me either. I had to learn to do things properly, and, as tackle cost money, it paid to learn quickly.

Time passed and gradually I improved. In the early days any fish was a real bonus, but several seasons in I was beginning to catch nearly every time we went out. Expectancy is a terrible thing in fishing: it murders the heady rawness of feeling you get from the first few fish you ever caught by suffocating it under a fixation with catching as many fish, or as big a fish, as you possibly can. Sadly, a bit like the first time you ever fell properly in love, or saw a magic trick, or rode on a rollercoaster, that exhilarating feeling of holding one of your earliest fish can never be matched by simply catching more of the same.

With the sheen fading from the silver scales of the roach I began to wonder what other challenges might be living within the depths of the Creek. One day, while quickly retrieving a red-fin roach along the Creek’s surface, a massive impact tore my fish clean off the end of the hook. My line fell limp at the rod tip and I turned to Grandad, near rigid with shock.

‘Pike, son,’ he said, with a solemn and knowing glance at the pathetic remains of my roach, which was now little more than a smattering of tiny silver scales descending to a murky oblivion.

I had just been humbled. That was a man’s fish and I knew I wasn’t ready to take it on, but luckily there was another, more pocket-sized, predator lingering close to my diminutive grasp.

The temperature gauge on my van tells me it’s a dispiriting 4°C outside. I flick the indicator to take a long right-hand turn at the roundabout by the football club, and steam happily away from the commuter traffic trailing into Cardiff for work.

It feels like the wrong day to begin this challenge – the Vale of Glamorgan strikes me as particularly numb and lifeless this morning: lumpen, cold and grey, like the contents of a mortician’s drawer. I turn up the fan heater and squeeze the accelerator.

It’s overcast too but that doesn’t bother me nearly as much. Big perch hate bright conditions. To be fair, even 4°C isn’t truly the end of the world – there’s plenty of fish willing to feed in those conditions; but this is the first major temperature drop after a sustained period of double digits, which is very bad news indeed as fish really dislike sudden changes in temperature, and, worse still, the opening frost of winter is forecast to arrive tonight. That’s an event guaranteed to put every fish in Britain off its food.

After a frost some fish species will remain on the bottom; hidden, in a trance-like torpor, just subsisting off their reserves until the warmer months stir them back to life. Others, like the perch, will adjust to the colder climes after just a few days and will gradually come back on the feed.

The worst possible time you can try and angle for them is just after a frost; the second-worst time is right now: just as it’s starting. By rights, I should have stayed under the duvet this morning, but I felt I had one very good reason for wanting it today more than most.

Fishermen are among the worst offenders when it comes to believing in ‘signs’. I’ve seen the most hardened atheist turn clairvoyant when it comes to the desperate search for a fish-filled future; scientific anglers who, no matter what the conditions, will only fish their lures and flies in a certain order; and those who sincerely believe that a specific choice of socks or the sudden appearance of an auspicious bird or favourite mammal can conjure a fish for the fishless. Even my grandad, a no-nonsense engineer throughout his working days, would never fish the river if there was even a hint of a westerly wind.

What was sticking in my craw that morning was that it was precisely a year ago to the day that I lost the biggest perch of my life: I simply had to go fishing.

A little perch is almost always every little fisher’s first ever fish. It wasn’t quite mine of course, but they were an ever-present pleasure in the Creek, ready to step in and save my blushes when a blank day seemed otherwise inevitable.

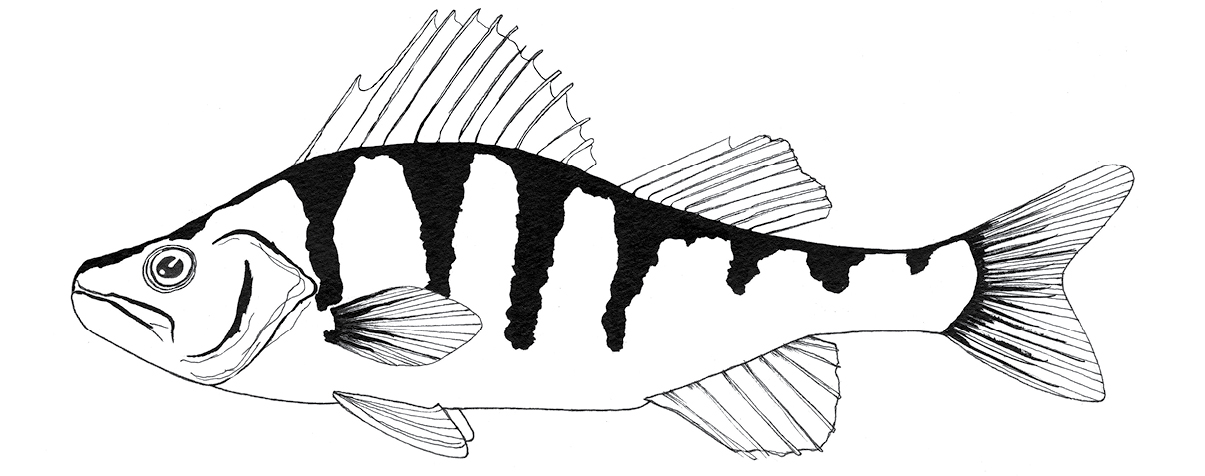

‘Like a Japanese Warrior in his medieval armour,’ intoned Jack Hargreaves in his 1951 classic book, Fishing for a Year; and what a perfect simile that is for this classy little predator. With its hard, sharpened gill plates, black eyes, and spine-tipped and sail-like dorsal fin, the perch is absolutely built for a fight; but it’s a strikingly handsome fish too: its flanks are marked by a series of immaculate black stripes blended perfectly over a dark olive backdrop. With striking blood-red fins and a whitened-cream belly that is wonderfully plump in the bigger specimens, it really is one of the best-looking of all the freshwater fish.

Unsurprisingly, it was one of the most in-demand fish to pass under the taxidermist’s scalpel in the Victorian era; but it’s the perch’s mouth that truly must strike the fear of God into any fish or bait unlucky enough to fit inside, for the perch must be the greediest fish ever to have lived.

Its jutting jaw is specially hinged, allowing its oversized mouth to engulf surprisingly large prey. As a boy I would often catch them fishing on lures intended for pike ten times larger, such is the perch’s capacity to sense weakness and an opportunity. When they are in the mood, they will bully their patch of water and intimidate others with a yobbish enthusiasm.

On the Creek we would catch them near boat moorings, reed-lined banksides or, more often than not, directly beneath wooden jetties: right in among the pilings, where they can leap back and forth from their ambush point. Clearly, they are comfortable in large shoals. I remember one astonishing day with my little brother when we simply could not stop catching them. Like shelling peas, we flicked them out one after the other from an area under a landing stage no bigger than a ping-pong table. Eventually, it got so embarrassing we had to stop and upended a keepnet filled with at least a hundred little stripy fish.

On a clear day I would observe the Creek’s vast perch shoals, tucked tight into the holes and structures they preferred, allowing their zebra stripes and dorsals to fuse with the reeds, wood or each other, till the individuals were near indistinguishable from the shoal. From here they would conduct their remorseless assaults: plundering the roach-fry like a marlin destroys a bait ball, sending their panicked prey scattering on the surface in great shimmering plumes of silver.

On occasion I would spot one or two that were clearly a lot larger than the rest: hump-backed and aloof, these were the adults. These wise old fish were given respectable space by the smaller fish in the shoal, most likely not out of deference, but because big perch have a cannibal’s reputation.

They would observe me with an infuriating indifference as I made cast after cast in their direction, never once looking even remotely likely to come to my hook. Eventually they would tire of my intrusion, and would simply disappear with a flick of the tail; leaving a boy with a face redder than his rod, kicking up clods of turf in wretched frustration.

The Wilson Encyclopedia describes a ‘mega-specimen’ as any perch over 3lb, and lists the British record at 5lb 9oz, but, as I write, the current record is now headed by two separate fish caught just a year apart, and which tipped the scales at a whopping 6lb 3oz.

What I wouldn’t give to catch such a perch. I can’t think of any other species where the gulf in skill between catching the smallest member and the largest is so vast. It has to be one of the biggest challenges available to the British angler. Once hooked the perch is unmistakable. The pugnacious jag-jag-jagging fight, as they repeatedly dive back for their cover, is like having your line attached to the sword of an Olympic fencer. It singles out the striped assassin every single time. In the bigger ones this pulsing motion is only magnified, till the shudders on your rod register with the force of a piledriver.

As a child, having blown my opportunity to snare a big one for just about the millionth time, I consulted Grandad on the appropriate method for snaring the larger of these princely predators. ‘The tail of a lobworm, nicked through the bloody stump,’ he opined simply, in much the same manner as a witch might recommend a wicked potion for curing warts.

‘Is that really all there is to it, Grandad?’ I enquired, my heart full of hope.

Grandad was a keen devotee at the church of lobworm; they were the only alternative bait he would consider when his maggots failed to work. He dug his mud snakes, the largest of the British earthworm species, out of the sweet-smelling compost heap he managed out the back of the bungalow. From there, he would roll them tight within long leaves of newspaper and stick them in his large white chest freezer.

I recall the first time he showed me his supply. ‘Don’t be shy about using a big hook; it’ll work, but, look, Will …’ He stopped and fixed me with his big brown eyes. ‘… big perch need patience. You can’t be jumping about and re-casting all the time. You have to learn to time it right: early mornings or the last hour of light.’

He placed his giant forearms on the chest freezer’s top and leant forward. ‘You must be prepared to wait for him to make the first mistake. Otherwise,’ he added, ‘there’s not much point in you even trying.’

In much the same way that I discovered collecting conkers was actually more fun than playing with them, I took to collecting worms with more enthusiasm and early success than catching big perch. Of course, Grandad had me pegged. Totally.

I had heard the best time to look for the biggest worms was in the dead of night, just after a summer storm, preferably on the outfield of a cricket pitch. That seemed like a ludicrous number of variables to me, and with night-time cricket matches in the rain particularly thin on the ground in my patch of Cambridgeshire, I took to re-creating a rain storm with a washing-up bowl filled with Fairy Liquid suds, and the tactical deployment of a gently wiggled garden fork. Once I got it right it was like raising Medusa’s hair from the turf. Up the worms would pop en masse, no doubt poisoned from their homes by the sudden influx of soap, and I would scoop them up and into my bait tin with unbridled glee.

One week later the largest and juiciest of all my incarcerated lobworms landed within an inch of a big creek perch’s mouth with a resounding thump.

It was the stealth equivalent of hiding behind a door for an hour to quietly surprise your mate, and then slapping him round the face with a draught excluder the second he walked into the room. Naturally the big perch flushed immediately from its hole in fright, leaving me sat impotently watching my giant worm squirm its way along the bottom without a single fish anywhere else in sight.

What was it about these cursed bloody worms? Perch holes and playgrounds: lobworms seemed to clear them both with ruthless efficiency.

For thirty seconds I waited, roasting from the inside out with a furious impatience. How did Grandad do it? When I did give up, I made sure I gave the turf the most solid kick I had in me before heading straight home to catch more worms, swearing blind that day I would never bother trying to catch big perch ever again.

After the sand eel was lost and the Wilson Encyclopedia found, it made sense to me to start my quest with big perch. Not just because they had such a presence in my childhood, but also because it was the perch that had slowly begun to ease me off my carp addiction in the months before the sand eel hammer blow.

It started with a few speculative casts with a worm a couple of years ago; purely to fill in time when the carp weren’t biting. I wasn’t expecting anything to happen, but, to my sheer delight, my float zipped away with a familiar jagging riposte and I found the swarms of little perch had been dutifully waiting for me, almost as if they had been following me around since I was a little boy.

With a bit more managed neglect of my carp rod, a slightly bigger hook and the careful chumming of the water with broken lobworm, I soon found I could even winkle out the odd larger perch in the shoal. Okay, they weren’t that big, perhaps only a pound or so, but I was at least aware that these were indeed the striped ‘monsters’ of my childhood memories and so venerated them sufficiently.

The following year I made my first concerted effort to target even bigger perch. I did some research, modified my tackle, and shipped in 200 live lobworms that I established in a garden shed bucket and fattened up on vegetable scraps. Within the year I had my first 2lb fish: a stunning, bristling specimen that scrapped all the way to my net in a heart-stopping account of itself. As I held it in my hands I felt a sort of electrical pulse of excitement that I hadn’t experienced since I was a boy. Just why had I wasted the last twenty years fishing almost exclusively for one species of fish? I slipped her back, the dorsal slicing the water like a serrated knife through an apple, and would meet the sand eel on my very next trip out.

In the past twenty years of fishing almost exclusively in stocked carp lakes I had inadvertently stumbled across a very modern phenomenon. With commercial carp waters sprouting up all over Britain, big perch have found a habitat where they can absolutely thrive. In these lakes there are generally no pike present to cull their numbers or compete for the baitfish, and barely any angling pressure from the hordes of Cyclopean fishermen targeting only carp. As a result the perch in these ponds have been allowed to grow to prodigious proportions. Out of the biggest fifty perch caught in Britain nearly half have come from commercially stocked lakes in the last decade; a staggering result that is hardly matched in any other fish species mentioned in this book.

Year on year the established perch records are being pressed and even the 3lb Wilson mega-specimen has seemingly become a happy resident in almost every carp pond you care to mention. You shouldn’t be foolish enough to think that means they are easy to catch; big perch will always continue to play their cards very close to their chest, and only the best of anglers will regularly snare the largest specimens. It took me two winters’ worth of outings before I had my first decent one, and another year before I had a brush with my very own perch-of-a-lifetime, right here, at the very venue whose gates I was swinging into.

White Springs is pretty much your blueprint for any commercial pond complex you care to pick in the country. It’s got a variety of manmade lakes offering everything from pleasure fishing for carp over double figures, right up to a specimen lake with carp over 45lb stirring up the waters. So far, so similar; however, what really set my pulse racing were the reports of the resident perch in one of the ponds: they sounded mega, even by the high standards of this golden age of perch fishing.

I read an article where the author details snaring not one, but three, perch over 3lb in a single session here, which he then topped off with a truly ridiculous fish of over 4lb. Surely, I thought, this had to be one of the greatest big-perch hauls in history, but a few clicks of the mouse proved these ponds had even more to give. A fish of over 5lb is resident here. I’ve seen its picture. It’s a brooding, menacing predator with huge flanks and an appetite to match.

Three-pounders, four-pounders, and even a five: if you were to place that against carp, it would be the equivalent of having a lake holding a fish over 55lb with a head of fish over 40lb as a back-up. It would be among the most celebrated fishing lakes in the country, yet as I roll down the tarmac road and into the complex it becomes apparent that I am going to be fishing the perch ponds almost completely on my own.

I settle right back into the swim where I lost the big one the previous season. It’s on a lake known as the Big Pit, an area of water where the White Springs management have fused two lakes together, removing the earthen bank between one lake, which resembled a small canal and held some of the big perch, and another, larger, rounder pond that housed some of the bigger carp.

I have to avoid those carp at all costs now. My perch tackle is light, so a hook-up with one of the lake’s golden mud pigs will necessitate a long and laborious fight which I’m most likely to lose, plus it will certainly scare off any of the big perch that I’m hoping to persuade to my hook.

This cold front will do me a real favour in that respect – carp really don’t like the colder months; but there’s still a chance I might snare one that’s ignoring the forecast, so to boost my chances further I’m avoiding all the baits I would commonly use to target carp (pellets, corn and boilies), and I’m also steering well clear of any parts of the pond where the carp might still be active: the warmer, shallower areas which get more of the limited sunlight, and those fishing platforms which have seen a lot of regular angling activity and feeding. This still might not be enough, though, so I’ll also be ready to cut right back on my loose feed of red maggots and broken worms if it looks like I’m attracting the unwanted attention of the Cyprinus carpio. Make no mistake, this is a seriously challenging prospect given the intensity of my addiction to that species – a bit like offering a free cigarette to a recently reformed chain smoker – but if I’m going to take this challenge seriously I have to focus my mind solely on the perch.

This corner of the pond absolutely screams ‘perch’. It’s the area with the thickest banks of marginal reeds, the largest overhanging bushes and, if my depth plummet isn’t lying to me, the deepest, darkest holes around.

I can almost feel that big perch’s presence; pressed up, somewhere in the darkness, tight against the sunken tree roots and reeds, perfectly camouflaged, waiting to strike me down with those wild black eyes.

I begin by scooping a dozen red maggots into my catapult. I’m aiming to keep these going in every minute or so. Hopefully the ‘little but often’ feeding routine will bring into the swim the shoals of little baitfish that the bigger perch like to feed on. If that fails, I’ve got the crutch of these broken lobworms to rest back on. Chopping them up into pieces will release a slick of worm’s blood into the swim: catnip for the big perch. The scent will draw them in, then they’ll find all the baitfish, then ‘bang’: they’ll inhale my irresistible bait.

I hook a juicy lobworm through the tail and give it an underhand flick right into the dark shadows at the foot of the reeds. I’ll have to be vigilant: any signs of scattering baitfish or big swirls could well be the perch’s dinner bell sounding. I may only get one chance to snare a really large one.

Gently, I tighten the line between my hook, the weight and my rod tip, till I can register a bite simply by watching for any minute movement at the end of my rod. Satisfied, I settle back into my chair; and immediately hook into a massive carp.

‘For fuck’s sake!’

The rod arches down to breaking point and the reel screams in deference as the fish ploughs directly between two small islands. I tighten everything down as much as I dare, and apply side pressure. My rod forms an almost perfect parabola.

Hold it, Will; just hold it. If it gets behind the islands it’s game over.

The line whines in the wind, I’m dancing on the very edge of catastrophe here, but finally I feel the great fish start to turn. Weakness: it’s hammer time. I reel down hard and gradually gain ground, steering the carp successfully back through the island maze towards me.

This is a nightmare. The worst possible start. I daren’t even begin to think about the damage this carp has already done to my chances with the perch. I prepare my net but the fish is still nowhere near ready; with one giant thump of the tail it cuts its passage straight up the pond, ploughing away from the islands, and my corner, and out into the open water.

That I don’t mind at all; it’s well away from my traps and there are no obstacles out there. Keep sustaining the pressure and let the rod do all the work. It’ll soon start to tire. I’m back in control now. It’s just a matter of time.

Actually, this might not be that bad after all. If the grand culture of fishing superstition is to be believed then all that is happening here is that history is repeating itself. This happened last year too. First cast: giant carp. Second cast: giant perch.

The fish reveals itself: it is a stunning ghost carp with golden-white scales and a dark-grey skull pattern framing its head. It’s a bit smaller than last year’s carp, but for some reason the ghost carp always seem to punch above their weight. I slip it into my landing net first time and walk the fish safely down the pond; as far as possible from my perch spot, and to a place where hopefully it can warn all its carpy mates not to come bothering me up in my corner.

Resettling after such chaos takes time. Lines and bait boxes are strewn everywhere. It’s important after any big fish that you don’t just cast straight back in. Heart rates and water need time to settle back into a rhythm and hurried casts can result in lost fish and tackle.

After that carp I feel like I’m chasing my shadow, ghosting right back into my mis-steps and mistakes from last year. I remember clearly my next act a year ago: I flung the worm straight back out before I was properly ready and not thirty seconds later the rod tip thumped down hard. I lifted, but I didn’t initially feel that familiar perchy fight: I felt a sustained pressure without quite the reel-stripping runs of a truly large carp.

‘A small carp,’ I supposed then, and bullied it back towards me.

It wasn’t till it was almost under the rod that I had the first obvious clue that this was in fact a truly massive perch. The rod suddenly buckled down as the fish dived hard for the wooden posts by my feet. I remember leaving my seat at that point, falling dramatically to one knee and leaning right across the water with my rod outstretched in my hand. The line grated up hard and horrible against the posts and I was convinced I was about to lose it, but, much to my surprise, the perch erupted on the surface right before me.

Time stood still; and, unfortunately, so did I.

I came to my senses at precisely the same time as the giant perch and made a hurried grab for my net just as the perch turned its giant head. It was so large you could have fitted a tangerine in its mouth, and with a single pump of its tail it brought my rod tip back down with tremendous force.

The next scenes unfolded in a bit of a blur. I realized, with sheer horror, that the line had somehow tangled intractably around the arm of the reel. I tried desperately to free it but big fish rarely give second chances and, in that split-second window of weakness, the giant perch freed itself from the hook and was gone. For ever.

It sounds ridiculous, but I bet if I had never seen that perch reveal itself on the surface I would have landed it. The realization that I had my dream fish within touching distance caused me to lose all reason and form. I changed from the confident bully into the horrified victim in an instant. It still makes me shudder at the thought.

‘Anyway. You can’t let that happen again now, Will,’ I tell myself for what feels the millionth time.

I catapult out another pouch of maggots and flick the worm back into the danger zone. Ice cool. I refocus.

Very sadly, history shows no interest in repeating itself. Several hours later, by the time I finally decide to give up and go home, the mercury has plummeted to such an extreme extent that my landing net has frozen solid to the grass. On the drive back, as my fingers come screaming back to life in front of the van’s heaters, I swear blind that this will be my last trip to White Springs this winter.

After last year’s disaster I have spent a week of my life traipsing up and down the M4 on a hundred-mile round trip, desperately hoping to snare that giant perch again. It has been as torturous as it was futile. I haven’t caught a single decent fish.

That all has to stop now. If I am to catch a record, I want it at least to have been fun. Not just me sat static at the most boring end of fishing, freezing cold and achieving absolutely nothing.

It would be all too easy now to simply blame my venue choice for my own shortcomings as an angler. There is nothing actually wrong with White Springs, and those spectacular perch certainly haven’t gone anywhere, but it is every inch the commercial fishery. From its sculpted islands to its trimmed shrubs and manicured fishing platforms, it is precisely the sort of place I was supposed to be weaning myself off during this challenge. If I’m going to keep coming to places like this, then I may as well just chuck the Wilson Encyclopedia in the lake and carry on catching carp.

I can hear what you are thinking: I bet if you had landed that big perch you wouldn’t feel that way. Of course I wouldn’t. But I didn’t, did I?

As the frost settled into something of a rhythm and temperatures stabilized once more, the memory of the various White Springs debacles began to fade. I took up a permit with my local angling club and filled my boots on big perch from a remote farmland pond, finally cracking the 2lb barrier, and snaring more than a dozen fish over 1lb 8oz in one quite remarkable evening. My confidence was restored. I hardly lost a fish that month, and felt far more comfortable with the haphazard rhythm of the big perch’s fight. In fact, I can quite honestly say I only broke sweat on a couple of occasions: once, when I accidentally locked the van behind the lake gates, and then lost the key, and then experienced my first serious breakdown; and next, while leaving the lake on another occasion, when I blundered directly into the path of a massive boar badger and almost shit my socks.

I wasn’t closing in on that Wilson mega-specimen, though, and knew in my heart of hearts it was probably time to take a long hard look at Grandad’s traditional techniques.

Really, as undoubtedly effective as worms clearly still were, I hadn’t done anything to update my approach in over twenty-five years; I’d just picked up from where Grandad had left me, rolling his worms into the giant chest freezer.

I began a trawl for new methods and was very surprised to discover that perch fishing was practically everywhere: multiple blogs, on the covers of magazines, all over the internet forums, and in many, many, viral videos. Catching perch seemed suddenly very ‘in’, and, dare I say, actually, a little bit ‘cool’.

Without a doubt, the single greatest piece of public relations to come out of the sport has been the impact of light-rock fishing (LRF) from Japan. In the past, lure-fishing meant shapely chunks of metal, spinners or spoons, and wooden ‘plugs’, moulded to resemble the features of a wounded baitfish and pulled through the water in a manner designed to fool predatory fish into a take. The trick of LRF is to take these basics and radically lighten the approach. In this way new, infinitesimally small spinners appeared on the market alongside thousands of micro-lures, -jigs and -jerkbaits made of ultra-lightweight rubber and malleable plastics in a bewildering array of colours, shapes and designs.

The masterstroke of LRF is that it has even made fishing for smaller predatory fish really exciting. For fishermen armed with short rods, matched with lightweight reels and hypersensitive braided lines, even the little wasp-like perch are a tantalizing target once again, their attacks registering on the subtle line with an extraordinary jarring force, every run, lunge and headshake transmitted down the rod with surgical precision.

LRF isn’t just for small fish though; most of our recent record-breaking perch have been caught using these tactics and, believe me, when you actually do hook into something substantial the feeling of that first heart-stopping run never leaves you.

Thanks to LRF, urban fishing is back with a bang, and it was on those previously overlooked waterways that I decided to focus my gaze now.

Armed with a packet of inch-long, rubber, snow-white lures known as ‘grass minnows’, I scanned through a long list of options for a big-city stripy. The obvious choice would be somewhere on the Thames. The perch-fishing pedigree of this river placed it somewhere among the very best perch rivers in the country, and, according to the perch record list, a 6lb 4oz unclaimed record was landed there just a couple of years ago by a man listed only as ‘Bill’. How cool is that? According to reports he had to be forced into declaring any element of his catch at all. I desperately wanted to meet this ‘Bill’; a perch-fishing Jedi master to my young Skywalker; but most of all I wanted to meet his perch.

Of course, only a fool would target a river as long as the Thames for just one fish, but Bill’s perch was far from the only big one. There’s barely a week that passes without a Wilson mega-specimen popping up somewhere on that river, either in the press or online, and the overwhelming majority of them are falling to the new LRF techniques.

I had only fished the Thames once before, from a town park in the leafy Berkshire town of Pangbourne, but even then I conspired to lose a very big perch that had engulfed a small roach just as I was about to get it into the net.

That was a ‘free-to-fish’ spot, and with a little research I soon found there were actually many more miles of free fishing along other parts of this iconic river. Perfect. It felt too good to be true. I bought a new, ridiculously small rod, coupled with an even smaller reel, and spooled up with braided line. Then I got very over-excited, very prematurely.

Within twenty-four hours Storm Barney had ripped through the nation, bringing gale-force winds and heavy rains in its wake. That rain didn’t let up for a week and soon nearly every river in Britain had swelled to bursting point.

I didn’t even need to leave the house to know for sure that the Thames would have gone into a serious state of spate; a sort of turbulent chocolate milkshake condition that would need at least another week to settle back down.

The free fishing was irrelevant and my lightweight gear was useless. I chewed my fingers down to stubs.

That’s not to say you can’t fish flooded rivers – some of the best catches I have ever made have been in the calm areas and eddies where fish are forced to take refuge from the chaos of the main flow during a spate; but LRF fishing in heavy water isn’t much fun at all. Even if you do manage to find clean runs away from all the storm detritus, getting the fish to see the lure in heavily coloured water is extremely hard, and getting your light gear to behave in a natural way is nigh on impossible.

I had an interview in London coming up that was within a stone’s throw of the Grand Union Canal. It wasn’t a patch of water I knew very well at all; in fact, I could comfortably count on one hand the amount of times I’d even seen it, but I did know that canals are always a sound bet when the weather is rough.

Canals had to be constructed to allow for the year-round passage of cargo during Britain’s industrial heyday. The canal engineers certainly couldn’t afford to let a few drops of rain stop traffic, so, with a deliberately even depth and flow provided by numerous manmade gates, locks and drains, you can get far more fishable water in rough conditions; plus, these days, with all the canal boats, low-slung bridges and concrete pilings, there are plenty of features for big perch to hide around and under as well. But the Grand Union Canal? In central London? Really?

The catch reports I read were very mixed, and in some cases downright dangerous. News articles detailed fishermen who were robbed of all of their gear at knifepoint, and others who had actually been pushed in by thugs looking for a laugh. The perch stories ranged from the ludicrous – one man claiming to have landed a seven-pounder from the Paddington area – to the plausible: a head of three-pounders dwelling somewhere within the deeper locks of Camden. But to get anything more specific than that required a more effective knowledge of code-breaking than the employees of Bletchley Park had.

I guess I could understand the need for some secrecy. Having put in so much work to locate a fish you wouldn’t then want every jolly perch fisher or poacher from W7 to E6 to descend on your mark and clean up; but some of the anglers had gone to truly ludicrous lengths to hide their knowledge: pictures of giant perch clutched by men who had blurred or blackened the entire background of their image, and others who had even gone so far as to obscure their own faces, as if they were part of a perch-based witness protection programme.

I didn’t really get it. If you didn’t want people to know where you were fishing then why bother putting up pictures of you with fish on the internet in the first place? Unless, of course, you are just showing off and hyper-inflating your own sense of self-importance by blurring your face and background, in which case, why not go the whole hog and come up with an entirely new social-media profile to complete your disguise, instead of posting with your actual name, actual address and actual school leaver’s details just one mouse click away?

What really irritated me on all of these blogs, pages and sites was the sheer amount of vitriol reserved for people who did not conform to the rules of the perch-fishing clique. Anglers who posted pictures with specific details of where their fish were caught were slammed for not caring about the welfare of the fish, and those who held their perch with arms outstretched in pride were ridiculed for making their catch appear bigger than it actually was, as if that matters at all at the end of the day. The worst of the wrath, however, was aimed at those who dared post a picture of their catch with a weight that was not deemed plausible by this, extraordinarily sad, minority of armchair anglers.

I remember one young lad in particular who caught the absolute perch of a lifetime from a town centre pond. It was a fish that looked every inch a record breaker: a glorious, solid-looking perch, which I would happily give away every rod in my household to catch. Doubtless, he was extremely proud of his catch, and, quite reasonably, thought it might be a good idea to post it on the ‘Perch Fishing’ Facebook group. However, for daring to post the location, weight and method of his catch, he was thrown to the virtual lions and torn to absolute shreds.

Within the hour the picture was gone, as was this boy’s Facebook profile, and no doubt any intentions he may have had to learn more about perch fishing from the adults.

If it had happened at that boy’s school they would have all been suspended for bullying, but on this platform I’m in no doubt it was pats on the back all round for another job well done. That’s what the internet is all about these days though, isn’t it?

And so it was as I watched legions of newcomers to the sport turned off for good, derided simply for wanting to publicly celebrate their perch, and feel part of this bizarre little club.

It had been a while since I had been in London but I felt I knew the city fairly well, having lived here for a year in my mid-twenties, a piece of my own history I shared with Grandad.

He had actually been part of the engineering team that had helped design the Thames Barrier in the 1970s, a pioneering construction built near Greenwich to stop the city from being flooded in the event of a storm surge or exceptionally high tide; but it’s fair to say Grandad revelled in telling anyone and everyone he met about what a truly miserable place he thought our capital city to be.

I remember the first time I visited as a teenager, and, on returning to the village, made the huge mistake of relating to him the following comment by a bus driver: ‘In London you are either looking at a shithole or living in one.’ Grandad, I recall, nodded along sagely, as if Buddha himself had crafted this singular piece of crude wisdom. ‘Well,’ he eventually said, ‘he’s right. Lonely too.’

I swore there and then that I would never go to London through choice, but somewhat inevitably, given the lack of entry-level employment opportunities for a budding Factual Documentarian in the Fens, I ended up in London anyway, and, to my great surprise, absolutely fell in love with the place.

London, despite its faults, is one of the greatest cities on Earth, and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. For me, by day, it may have been: ‘I simply can’t understand why you’re still stood in shot and not bringing our sandwiches’, but by night I was free to enjoy deliberately long strolls home in the darkness, through the buzzing Caribbean markets of Shepherds Bush, along the Royal Parklands, and down past the glitzy West London casinos where I watched Manny Pacquiao knock out Ricky Hatton live from the MGM Grand, and once lost a month’s wages in just twenty minutes.

For a young man from a small village simply living in London was like getting my own star on the Hollywood Boulevard. I could not believe I was living in the capital and seeing instantly familiar sights like Tower Bridge, Big Ben and Piccadilly Circus with my own eyes and not just on TV. It was the sheer scope and cultural diversity of the place that truly blew my socks off though.

‘London isn’t a place at all. It’s a million little places,’ commented Bill Bryson, and I have to say I wholeheartedly agree. I feasted on all the pleasures to be had by throwing myself fully into this city’s life and began to wonder if Grandad had simply been overwhelmed by it all.

Of course, it isn’t fair to write anywhere off with a sweeping statement, but having now lived in several big cities I have to say they can dish up a very special brand of isolation if you let them.

When faced with such diversity, opportunity and choice, to be incapable of seizing any of it for yourself, through no fault of your own, is to feel like the loneliest leper in the colony. The city then becomes the problem, and will provide evidence for your chosen prejudice wherever you wish to seek it out.

As much as I loved and appreciated all the parklands in London it never once occurred to me that I might be able to fish the canals. In my mind they were irredeemably dirty, the haunts of pimps and muggers and certainly not places to be spending any of my free time in. Whenever I peered into them I saw not near limitless opportunity to fish, but waste and weed, beer bottles and piss; an environment devoid of any life worth looking for.

It’s extraordinary looking back to think how easily I turned my back on fishing that year, and so it was that the delights of the Grand Union Canal remained hidden from me, until today.

My alarm sounded at a little past 6 a.m. I was staying with friends right out in East London. Ordinarily this would pose a real barrier to a day’s fishing in the city centre, as just the thought of piling on the Underground during rush hour with all my fishing tackle is enough to give me heart palpitations, but that is the beauty of LRF: no one would even have to know.

Just what do you wear for an interview when you know you’re going to spend the rest of the day fishing? I suppose the obvious answer would be to favour whichever of the two activities is more important to you and dress accordingly; but that’s a dangerous path for me to be walking down and one I suspected wouldn’t ever lead to an economically sustainable future, so I had opted for a halfway house: fishing trousers paired with a smart shirt and my fishing jacket to go on top, but within moments of boarding the Tube it becomes apparent that I have got it very wrong indeed.

In the bright light I realize I had been happily spraying Lynx Africa deodorant over what is quite obviously a large circular patch of fish slime on the breast of my jacket: I smell like a teenage boy who has just rolled along the floor in a fishmonger’s and then stuck a shirt on.

We pause at Stratford and my aroma wafts in and out of the doors as commuters stream on. A few people scrunch up their noses in disgust, so I do the same, with a shifty sideways glance in an attempt to palm the smell off onto some other unfortunate on the Tube.

Thankfully I’m ignored. Smells on the Tube are simply another inconvenience to add to the thousands of others these Londoners will have to face down today.

I wonder who else here might want to go fishing for a half-hour and what a difference it could make to their day. We pull into Liverpool Street station and dozens of smartphones flicker into life. Emails are coming in. Even down in this hole you can’t escape work. These people don’t actually have half an hour: they are 24/7 slaves to their emails and work.

I’ve been in those offices. You procrastinate through half the day but wouldn’t dare admit you could get your work done in half the time; you eat your lunch at your desk and then wait to be the last person to leave at the end of the day; you send emails in the middle of the night to give the impression of diligence, when in fact all you’re doing is confirming your total servitude to a group of overlords who’ll never even notice the extra hours you put in.

We’re losing out on our leisure time right across British cities and largely it’s a problem of our own making. I moved from this city, worked fewer hours, got out more, and surprisingly got a lot more work done as a result.

Capping the mind-bending and inefficient seventy- to eighty-hour weeks made me much more focused when I was in work, and much happier when I wasn’t. I was largely getting to do what I wanted to do outside of work (which was fish) and I slept much better due to the increase in physical activity and fresh air.

I’m determined to prove that it is still possible to go into work, even in our capital city, and find some time to fish somewhere nearby; but it doesn’t even need to be fishing – you can do whatever you want to do with your time as long as it’s not illegal and you’re back in work on time. The only thing I ask is that if you are a boss employer that you don’t read this to mean that I’m promoting the idea of fishing in the lunch break purely to increase productivity for your company: this is about my readers escaping your clutches during the break they richly deserve; it’s for them, about them, and your work doesn’t come into it – in fact I recommend you try it out for yourself as long as it doesn’t become an official ‘work outing’, ‘a team-bonding exercise’ or something else as excruciatingly lame.

A man spots my rod so I give him a little smile. He looks at me with large, doleful, baggy eyes: ‘Get me out of here,’ they plead.

My interview finishes at a very agreeable time. I think it went well: they didn’t once mention the smell from my jacket and I reckon they thought the fishing gear was actually pretty charming.

Stepping out of the shiny glass building and onto the Euston Road it’s clear I’m not going to get everything my way today. The heavens open and it starts pitching it down hard. Clearly, Storm Barney hasn’t let us go yet. I pull my cap over my eyes and head towards King’s Cross station.

In keeping with most areas around major train stations the world over, the immediate vicinity of King’s Cross is truly one of London’s grimmest areas. It really shouldn’t be – the station itself is full of Victorian splendour with its neat bricks, grand arches and glass façade, and just down the road is the equally stunning St Pancras Renaissance Hotel and British Library, but the fast-food restaurants, ugly coffee shops, horns, sirens and shouting give it a feel of a place where people would only ever wish to arrive or leave.

Moments later I felt like I was in an entirely new city. The black atmosphere diminished with every squelching step I took down York Way; there was water around here for sure, and it had already cast its comforting net wide down this street.

I pop my head over a low wall, hoping to spot it, but only find rows of parked trains. A little further on I spy the unmistakable shape of a bridge, but it’s got traffic piling over it and doesn’t look like a particularly inviting spot for my first look at the canal. You can’t mess up your first approach to water. It has to feel right; you’ve got to give your patch space to display itself in its best finery – otherwise you might find yourself writing the water off prematurely and miss out on something truly special.

I take the next right down a narrow alley. I’ll catch her out further downstream. Soon I’m passing behind a posh business building, and there, at the alley’s end, the world opens out splendidly into wonderful calm water. This is Battlebridge Basin. Victory.

It is hemmed in on all sides by up-market housing developments and the noise from King’s Cross is totally suppressed here, leaving this blissful oasis jutting fully 150 metres inwards from the main flow of the canal.

It’s wide too, fifty metres across I later learn, and, better yet, it has relatively little weed and no obvious ‘no fishing’ signs: the perfect place to have my first speculative cast.

I extend my telescopic travel rod and check the sharpness of the hook point by gently pressing it against the cuticle of my thumbnail. There are not many places to actually cast a clean line. The rows of brightly coloured canal boats on the far side look well worth a chuck, but on this bank I’ve got about fifteen metres of the alley end and a covered walkway leading across a marbled floor at the back of an architectural firm. Still, fifteen metres is better than nothing, and there is at least enough room to put a couple of long casts into the centre of Battlebridge Basin, and probably a couple more along the weeping brickwork running along the water’s edge.

I’d better get on with it, at any rate; I’m being eyeballed suspiciously by a security guard with biceps like coiled ropes.

The grass minnow plops into the drink and the time it takes to settle on the bottom tells me that this place is a hell of a lot deeper than it looks. From this point on, I’m fishing on faith and feel.

The braided line and soft rod are incredible; I twitch the minnow through the water and can feel every single bump, nook and cranny, as I make my first retrieve. The rain pours on the surface, flattening it and obscuring any potential signs of schooling baitfish, but I don’t mind that at all as the water is painfully clear so a bit of natural cover plays into my hand and obscures my outline.

I’m going to have to box clever today. There’s no point taking all my time to cover every single inch of water: the fish are either there or they’re not. I need to target specific features: something that casts a shadow and makes its residents feel safe. A couple of tries in each spot and then move on; accuracy, a methodical retrieve and determination are the keys to success here.

I can’t be a river snob either; the perch in this canal are just as likely to be living inside a car tyre as in a bank of reeds; it’s only us humans who get really fussy about the look of our real estate.

I fish between the canal boats, right along a thick ribbon of duck weed, under my first bridge, round a submerged traffic cone and along the length of a flat-bed trolley. No luck, but I’ve got to stay confident. Crossing a road out of the Basin I pass a sign giving fishing the thumbs-up and immediately feel buoyed. This place just feels right for a fish.

The next likely feature is another bridge right opposite the King’s Cross Theatre. I’m going to be leaping from bridge to bridge like a troll today. The rain clearly isn’t going to stop so they’ll be my only possible shelter, but the artificial darkness will also appeal greatly to the perch.

A couple of speculative casts into the murk bring my first proper take, but it’s short-lived: a single spirited headshake sees the hook easily disgorged. A pity, but a positive sign for sure. I must be doing something right.

I try again, taking care to slow my retrieve right down, and this time the hook finds something far more solid: but this is no fish.

I heave hard and get nothing back bar unyielding resistance. Obviously I’ve hooked into a heavy piece of solid waste: a trolley, a washing machine or perhaps something more sinister? I try and change my angle but there is still no give. This will have to be my first donation to the canal then. I snap the braided line under the strain.

The very best of fish live in the hardest places to catch them. Of course they do; they’ve grown in age and weight by being canny feeders, avoiding bigger predators, and picking the best spots to ambush food, but here that doesn’t mean supple tree roots or the soft tendrils from an overhanging bush – this is solid city centre litter dumped off the bridges by the lazy and feckless, in short: a tackle graveyard.

Another cast yields another aborted take, but this extra scrap of evidence allows me to narrow down the size and location of the fish.

It’s a small perch for sure, hidden somewhere tight against the heavily graffitied far wall. There’s no walkway over there so it is clear of human debris, but right in the middle of the canal is a ceiling fan and a billowing white sack. It’s a tough cast. I steady myself. I reckon I’ve got one more crack at this before the little fish spooks for good.

‘Any luck, mate?’ comes a thick West African accent from over my shoulder. I turn to meet a large man in full train guard uniform, his head topped with an immaculate black cap.

‘Not yet, mate, just had a take down here but I missed it, I think.’ We both look into the water. ‘Ja. There’s fish here all right.’ He leans over the railing, hoping to spot one on demand, and then gobs into the canal: ‘It all depends on the weather.’

I ask about his job and it turns out he isn’t a train guard at all.

‘It’s just a good thick coat and a snappy hat, don’t you think?’ I nod in approval and smile. I haven’t heard the word ‘snappy’ for over twenty years.

‘Plus you get plenty respect on the train.’ He laughs heartily.

My new friend and I both agree that there is a little perch under the bridge but, after a couple more casts, we surmise he’s probably not going to get caught today.

He shuffles off and so do I, downstream, passing Camley Street Natural Park, which had a couple of volunteers gamely tending to the shrubbery in the torrential rain, and on into my first lock.

St Pancras Lock is really very striking. A cute little whitewashed cottage guards the thick oaken lock gates and a string of canal boats line up along my side of the bank.