CHAPTER ONE

PROCESS IS PURE

Most people, when they see an ad, never think about how it came to be. In fact, people don't consciously engage with most advertising, period. It's noise. It's part of the landscape. It blends in. And for the same reason you're unlikely to notice any particular tree during a walk through a neighborhood park, you probably won't pay any attention to a television commercial, billboard, radio spot, web banner or any other branded message unless it's different in some significant way. We've convinced ourselves that we've seen everything before. That makes advertising a very tough business.

Those great ads that do break through — the very best of the lot — are those that do the job for the client (they communicate about the product and satisfy strategic objectives) and also leave consumers happier, wiser… somehow better for having engaged with the ad (they deliver a “gift” in exchange for their attention). When an ad sells and does so with great style, it's a thing of beauty. But when ads simply do one or the other, they fall short of fulfilling their potential. The creative folks that make ads every day strive to find the right balance of the two.

Advertising is a thoroughly collaborative business. Inside ad agencies, teams of professionals who specialize in marketing, research, media, technology, production and creativity (the list can go on, depending on the project) work together to serve the client's needs. It makes sense, then, that just about every ad you see that's selling a big brand is the end product of mammoth interaction — the sum of many edits, revisions, restarts and critiques by many different people. Everyone's got fingerprints on the work.

Within that collaborative machine, creative directors supervise the art directors (the visual people) and writers (the word people) working on a specific account. Typically, one art director and one writer are paired to work together to generate ideas, but creative teams can vary in size (and sometimes specialty) if need be. The creative directors are the more senior and experienced pros who started out in art direction or writing. These days, they guide the work of their own teams, assuring that it meets the agency's standards and (with any luck) the client's, too. The creative ideas they generate get circulated throughout the agency; those determined to be the strongest are shared with the client. The client's evaluation of the work can send it back for revision, push it through to see the light of day as a finished ad or kill it in favor of another approach. (That's a woefully simple summary of how things can happen, but you get the idea.) A great idea can run that gauntlet, but it can seem miraculous whenever it happens.

At the center of all this (and, regrettably, too often overlooked) are the individuals who've invested their big brains in this enterprise. They might have been geneticists or screenwriters or architects or economists or poet laureates, but they chose to make advertising. They'll tell you they do it because they love it, and because they couldn't imagine being happier doing something else. They're creative people, yes… but of a rare breed. They don't create as a means of pure self-expression. Instead, they enjoy the challenge of doing something imaginative/surprising/amazing/smart/beautiful that will meet someone else's specifications and solve their problems. They don't sign their works of art. They labor in anonymity. Think about it: In this business, a writer can pen a phrase on every American's lips (“Can you hear me now?”) but only his mom gives him credit. An art director's colorful vision of dancing silhouettes enjoying the iPod is more ubiquitous than Warhol, but museum curators don't know her name.

We're fascinated by the creative minds that answer the call to be professional creatives. These individuals are at the core of everything that makes advertising interesting. They are true artists in the sense that their work is constantly broadening, enriching and challenging our concept of that term. Each of them brings a unique intellectual perspective to the work they do, and their talent is a hot commodity. Agencies (the good ones, anyway) understand that they have to recruit the best brains available. After all, their piece of a 500 billion dollar industry is at stake.

For that reason, these creatives understand more about their own brains than most of us do. Working in this business, they've honed their own creative process for developing ideas. That personal process, we believe, is representative of advertising creativity in its purest form.

Creative directors, art directors and writers see the mind as an instrument. It's the most important tool they use at work.

Creativity is advertising's most valuable resource. Studying, understanding and appreciating the nature of the creative process, we believe, should be a priority in the scholarly realm; this area of inquiry holds the potential to accentuate advertising's significant contributions to culture and quality of life.

Remarkably, the study of creativity and the creative process is still rather new. This chapter will offer you an overview of research, definitions for some important terms, theoretical insights and a sense of how advertising connects to it all.

WHAT IS CREATIVITY?

In order to study something, it's essential to start with a definition that precisely describes the topic of interest and distinguishes it from others. Historically, that's been one of the major obstacles to the study of creativity. The term “creative” feels very big, and it's often used to describe anything that's new, different, odd or unexpected. Even though it's easy to carelessly throw the term around, “creative” also carries connotations of something special, rare or valuable. It seems intuitive, therefore, that the true definition of the word must be somewhere in the middle.

To complicate matters further, for centuries now, creativity has also been attached to the magical or supernatural. It's been the topic of much romance and fantasy. The classical Greek philosopher Plato (c. 427–c. 347 B.C.) explained that goddesses known as the Muses inspired mankind's artistic creations, attributing no innate creative agency/ability to human beings. Hundreds of years later, the poet Alexander Pope (1688–1744) was celebrating his own Muse and Rudyard Kipling (1865– 1936), author of The Jungle Book, cited a “daemon” that lived in his pen, perpetuating the link between creative works and otherworldly forces.

Over the past century, scholarly research on creativity was confounded by a number of issues. First, and perhaps most significantly, creative thinking isn't a readily observable phenomenon. While we might be able to see ideas or other creative products realized, trying to figure out how or where they originated in the human mind is a different story. So far, science hasn't developed a viable method for watching us think in real time and certainly not at a level of sophistication that can differentiate creative thinking from any other type.

Second, creativity was long considered a peripheral psychological phenomenon, meaning that most experts viewed creative thinking as either a secondary (less significant) cognitive function or one that wasn't commonly experienced by most people. And, as we've already noted, the lack of a clear and concise definition of creativity was a great obstacle in getting studies off the ground.

Creativity as Problem Solving

Despite the fact that the study of creativity remains relatively new, a more rational, focused and practical view of it has begun to emerge. The most widely accepted scholarly definition of the term now frames it as a problem-solving activity. However, not every solution to a problem is necessarily a creative solution.

Harvard University professor Teresa Amabile, in her book The Social Psychology of Creativity, identifies two types of solutions: (a) algorithmic solutions (preexisting, linear series of steps to be followed); and (b) heuristic solutions (new methods developed in the absence of algorithms). Clearly, a “creative” solution would be considered heuristic in nature rather than algorithmic, because it represents a new approach for solving a problem.

In advertising, the challenge to solve a client's problems is ever present. How can people be convinced to drink more milk? What can be said about tires that hasn't already been said? Is there a way to position this personal computer as the hip, youthful alternative to the market leader? Algorithms abound. Formulaic approaches (those tried-and-true templates that clients love) are everywhere. The best art directors and writers will look for a new (heuristic) approach for crafting brand messages in a crowded, copycat category.

Novelty

Novelty, in fact, is another essential element in defining creativity. Case in point: Scholars in the field of aesthetics argue that novelty is a key characteristic for evaluating works of art. Experimental research evidence suggests that creatively productive people prefer novelty, attributable to a characteristic open-mindedness and distaste for the traditional or commonplace in everyday life. It is important to note, however, that the “new” or “novel” can be derived from the old; the creative mind can combine or synthesize existing material to yield new products. Some may suggest that “there's nothing new under the sun,” but creativity defies this perspective by discovering new combinations, connections and relationships.

Agency creatives live in constant fear of becoming hacks. There's great pressure to avoid ripping off (whether by accident or on purpose) someone else's work or producing something that is boring and flat. Of course, it can be hard to discern whether or not an idea for an ad is original when you're so immersed in the business. Luke Sullivan, group creative director at the agency GSD&M and the author of Hey Whipple, Squeeze This: A Guide to Creating Great Ads, suggests that art directors and writers should admire good work that others do but then promptly forget it. Perhaps easier said than done, but wise words nonetheless.

Usefulness

If we think of creativity as a method of problem solving, it's easy to understand how the creativity of an idea could be measured by how useful it is. If we solve a problem, the method used for solving it was beneficial to us. This also introduces the idea that creativity makes a valuable contribution (at some level) in people's lives and isn't purely self-serving. There's a sense that creativity has an inherent social value. Arthur J. Cropley, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of Hamburg, insists that creative ideas must be shared and “accepted or at least tolerated” by society, which he calls “socio-cultural validation.”

No matter how “creative” we might consider an ad or a campaign to be from a variety of other perspectives, its ability to fulfill the client's objectives is key. Many industry award shows reward agencies for producing work that's funny or beautiful or represents a unique approach. However, if the advertising isn't doing the job for the client, it's unlikely to remain visible long enough to have a lasting cultural impact.

Everyone is creative.

And by that, we mean everyone has the potential to be.

Creativity Defined

The definition of creativity that we like to use encompasses all of the important criteria that we've outlined below.

Creativity:The generation, development and transformation of ideas that are both novel and useful for solving problems.

Notice that we frame ideas as the product of creativity. We find that this resonates with our advertising students, whose credentials as “idea people” will be crucial to their success in the classroom and beyond.

For ad professionals, this definition probably reads a bit like a job description. As you'll hear many of them say, “You're only as good as your last idea.”

But hey, no pressure.

WHO IS CREATIVE?

Ask a simple question, get a simple answer. Everyone is creative. And by that, we mean everyone has the potential to be. Potential is a key word.

In the Handbook of Creativity, cognitive psychologists Thomas B. Ward, Steven M. Smith and Ronald A. Finke insist “the capacity for creative thought is the rule rather than the exception in human cognitive functioning.”

That's a pretty powerful statement. Read it again. It means that every normal, healthy human being on the planet is born ready to be creative. But note the word “capacity” there. That's where potential figures in. Creativity is, we believe, an act of will. If you want to think creatively, you can. If you want to be more creative than you are now, you can be that, too. But if you don't believe that you're creative or (worse yet) don't want to try it, don't expect anything much to change.

We try to help students believe in their own creative ability by framing it as good old-fashioned hard work. It's not magic (even though some of advertising's rock stars make it seem so). Hours of thinking, sketching, writing and rewriting will pay dividends. Quality ideas come from great quantities of ideas. Amazing creative work doesn't come easy, but that wonderful sense of accomplishment in finding the answer makes it all worthwhile. These are our mantras.

We encourage students to figure out how they are most creatively productive on a personal level. We don't make anyone creative; we help facilitate their journey. Finding your own process comes from a lot of trial and error (and let's be real here, there's lots and lots of error involved). Each student will experiment with different thinking techniques, a variety of work environments and all sorts of idiosyncratic philosophies and motivations. But eventually, things will start to click. As they taste success, they'll begin to trust the protocols they've developed. They'll settle into patterns that feel comfortable and yield the best results. Watching this happen is one of the best parts of our job.

Although no two people find ideas in exactly the same way, it's pretty clear that some aspects of the process are universal. In the next section, we'll offer an overview of research on the creative process and some related concepts.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

It seems oddly appropriate that the most significant theory about how the creative process works came from an unlikely source. Graham Wallas (1858–1932), a British political scientist and sociologist, proposed one of the first significant models of the creative process in his book, The Art of Thought (1926). Although he spent most of his life teaching and writing about politics, he was fascinated by human nature and how it influenced the development of society.

Graham Wallas (1858–1932)

It seems oddly appropriate that the most significant theory about how the creative process works came from an unlikely source.

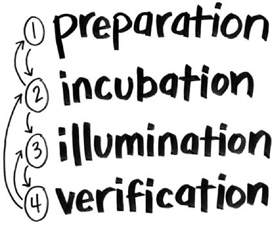

The Four-Stage Process Model

Wallas believed the creative process could be described as a series of four stages:

Preparation: The problem to be solved is carefully considered and resources are gathered in order to confront the task. The conscious mind is focused on the problem.

Incubation: Drawing upon these resources, consideration of the problem is internalized and becomes a largely subconscious activity. The mind makes connections more freely and abundantly.

Illumination: Possible solutions to the problem transition from subconscious to conscious thought. This is a moment of insight and optimism.

Verification: Solutions are tested and may be applied if shown to be viable.

Inherent to Wallas's model are several important assumptions. First, his conceptualization of the process makes it seem relatively simple. This was counterintuitive for many people back in 1926 and remains controversial in some circles today. In response, we'd argue that Wallas's four stages represent the more universally experienced facets of process but don't prohibit examination of the phenomenon in greater depth. Preparation, incubation, illumination and verification are also described as sequential, discrete stages. Wallas believed that they are experienced in the order presented and don't overlap. However, he did propose that the creative process is recursive in nature, meaning that any of its stages can be revisited, if necessary, once they've been completed in their original sequence. For example, if solutions tested at the verification stage are not shown to be viable for solving the problem, an individual might decide to continue thinking (return to incubation) or start all over again from scratch (restart at preparation).

Not only does the Four-Stage Process Model resonate with advertising students, it also parallels the day-to-day work of ad professionals as well. In the agency setting, creative teams typically receive documents called creative briefs at the start of work on a new project. The creative brief (if well written) offers a summary of important research that then kick-starts that creative process. It also articulates the big problem(s) that advertising needs to solve for the client. Art directors and writers spend a lot of their time “incubating” about problems before discussing ideas with their partners and identifying the best possible solutions. Creative directors then consider this work and offer their advice and input. A few sound concepts are eventually presented to the client, where the ultimate verification moment happens. Based on that verdict, the creative team will know whether it's time to move ahead with production of the work or to go back to the drawing board. Thank goodness it's a recursive process, right?

More than eighty years later, Wallas's model is still the most famous and influential proposal for understanding how creative thinking unfolds as a process. The vast majority of models offered by other scholars bear a strong resemblance to Wallas's work. Hungarian mathematician George Pólya (1887– 1985) proposed a model of the creative process that included a period of post-verification analysis (he called it “looking back”). Philosopher John Dewey's (1859–1952) book, How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process (1933), described a problem-solving process of “reflective thinking,” including a “pre-reflective” phase that closely parallels Wallas's preparation and incubation stages. The powerful influence of the Four-Stage Process Model is well documented and persistent. The terms preparation, incubation, illumination and verification have become well known and widely accepted in both scholarly and professional contexts.

In 1944, advertising executive James Webb Young (1886– 1973) acknowledged Graham Wallas in the introduction to his book A Technique for Producing Ideas, noting that “[Wallas] arrives at somewhat the same conclusions” about the creative process but that “what follows has seemed to have a particular usefulness for workers in advertising.” Webb's explanation for how advertising ideas are generated was indeed reminiscent of Wallas's model, but Webb insisted that he “discovered” Wallas after developing his own theories.

The Structure of Intellect Model

Another important contribution to our understanding of how the mind works (and thinks creatively) is the Structure of Intellect (SI) model created by J.P. Guilford in 1967. Guilford, a psychologist, appreciated the interdependent relationship between human intelligence (the sum of a person's knowledge) and intellect (a person's ability to use knowledge and generate new ideas). The Structure of Intellect proposes that there are three dimensions of intellectual abilities:

Contents: The sum of our knowledge (our intelligence) — everything that we know and the various types of information represented there.

Operations: How we use knowledge — the various types of manipulations that we bring to bear upon our intelligence.

Products: New knowledge or ideas that are the results of thinking.

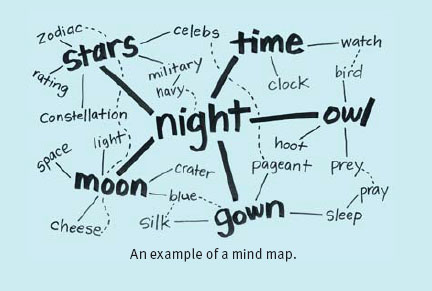

The “operations” referenced in SI include “thinking strategies” which can be learned and practiced, providing more evidence that people can develop their creative ability if they are motivated to do so. Most of the advertising creatives we know have their own favorite techniques for finding ideas. For example, some are list makers (e.g., lists of product characteristics, lists of alternative uses for a product, lists of places where the product could be used), and others enjoy sketching mind maps (a terrific divergent thinking tool developed in the 1960s). We share these techniques (and many others) with our students. With experience, each person decides which of these thinking tools work best or might be most useful in certain situations. They lend a bit of structure to process and help reduce some of the anxiety presented by a blank page.

Essentially, SI helps us to understand intellect as a broader, richer concept encompassing how we think and how we leverage our intelligence in doing so. Guilford's work serves to augment our understanding of the processes associated with creative thought and complements the broader framework represented by Wallas's model.

Domains of Creativity

Creativity isn't limited to the fine and performing arts, of course. It manifests itself in just about everything human beings make or do. It's part of groundbreaking mathematical formulas, site plans for urban gardening and every seasonal vaccine against the flu. Although the theories and models we've discussed so far describe how the creative process works in general, a growing number of scholars believe that creative thinking may happen in different ways across the variety of contexts in which it is applied. This idea is called domain specificity. The term “domain” can refer to a body of knowledge or, better suited to our discussion, a particular profession or line of work. In his book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, psychology professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls domains “primarily ways to make a living,” adding that they are possibly “the best evidence of human creativity” because we built them ourselves.

If you think about it, it does seem intuitive that the creative process a choreographer uses to develop a new routine might follow different protocols than those an art director/writer team might use to develop an ad campaign. However, it's also a safe bet that both choreographers and advertising pros engage in preparation, incubation, illumination and verification as part of the work that they do. So, accepting the idea that the creative process might be adaptable to a particular domain shouldn't invalidate the more general models of the creative process. Instead, this capacity speaks to the great problem-solving nature of creativity itself.

We don't know much at all about how the ideas behind great campaigns are developed or how the minds of art directors and writers find them.

Advertising is a domain, as are dance, architecture, chemistry and engineering. Domain specificity suggests there's a creative process signature to every business. Certainly, we see it in ad agencies (on a macro level) as clients, account planners, creative teams and other parties interact and follow established protocols to get the work done. More specifically, we can also observe processes for writing creative briefs and preparing pitches. We don't know much at all, however, about how the ideas behind great campaigns are developed or how the minds of art directors and writers find them. It appears we have more work to do.

Putting the Creative Process to Work

If you're a creative thinker, you use your mind in ways that everyone can, but too few actually do. You like solving problems. You embrace challenges. You use your creative ability in every aspect of your life, at work and at home.

We've discussed the idea that the creative process is universal in the sense that there are stages we all experience. We all draw upon our intelligence as the raw material for developing new ideas via the intellect.

However, we apply the creative process in a variety of different settings to accomplish a variety of different tasks. Consider the daily life of an executive chef. She spends her days running a kitchen, hiring staff, monitoring costs, rewriting menus and overseeing the operations of the restaurant. She might even prepare some food now and then. Each of these responsibilities requires special expertise and each presents its share of problems to be solved. Broadly speaking, cooking is the executive chef's domain and she uses her creative ability to perform in that context. But she's not always at work, of course. At home, she enjoys gardening and is looking for a space to plant fresh herbs. She's trying to figure out the best way to tutor her daughter in algebra. And her husband wants her help arranging the furniture in his new office. Hmmm. Our executive chef finds all sorts of applications for her creative problem-solving skills.

Creativity-Relevant Processes and Domain-Relevant Skills

Creative thinkers adapt their skills to address whatever problem is at hand. According to Harvard professor Teresa Amabile, these can be broadly categorized as creativity-relevant processes and domain-relevant skills.

Creativity-relevant processes incorporate more intuitive and generally applicable ways of thinking that help us generate exceptional (read: more creative) solutions.

Here are some examples of creativity-relevant processes:

looking for solutions that aren't as obvious to others

looking for solutions that aren't as obvious to others

throwing out old strategies and pursuing new directions

throwing out old strategies and pursuing new directions

appreciating and being comfortable with complexity

appreciating and being comfortable with complexity

appreciating and being comfortable with ambiguity

appreciating and being comfortable with ambiguity

refusing to prematurely pass judgment on ideas

refusing to prematurely pass judgment on ideas

Amabile proposes that those who possess these abilities will find use for them regardless of the domain in which they are applied.

Alternatively, domain-relevant skills are also essential for creative thinking but are not used in every context. Instead, they are applied when we are solving problems in our particular line of work. For example, knowing how to simplify an equation is an essential skill for anyone tutoring students in algebra. It's valuable in that particular domain. However, that skill likely wouldn't be as valuable when writing poetry. Domain-relevant skills can be acquired via education and include a person's innate abilities or talents in a particular area.

What are domain-relevant skills for art directors and writers? You could fill another book with all of them! Art directors, for starters, need to understand the principles of design and layout, appreciate the nuances of typography and know how to use the latest software. Writers must love words, know how to use (and not abuse) a thesaurus and read more than they write. And both of them should bring all the creativity-relevant processes they've got.

Motivation

In life, there are many things we don't enjoy doing. Everyone knows that. What isn't always clear, however, is that we usually don't do things particularly well (or at all!) unless we derive a benefit. Whatever that benefit is, it constitutes our motivation for performing the task.

Creative problem solving requires motivation, too, because it's not easy. It will always take less of your time and energy to apply someone else's solution, to employ the algorithm. That's one of the reasons why you often hear creative thinkers talking about how much they love their work. That passion for whatever they do is a powerful catalyst. It sustains them through periods of difficulty and frustration. It makes success all the more rewarding.

There are two types of motivation. If you are engaged in a task because you find it personally enjoyable and beneficial, that's called intrinsic motivation. It comes from within. This form of motivation is clearly linked with your own identity, personality and interests. If you are purely intrinsically motivated, you don't care what anyone else says or thinks. You're doing something because you want to, and that's reason enough.

Sometimes, of course, we do things for other reasons. If you are engaged in a task because you will derive an external benefit, you are (at least to some degree) responding to extrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivations can take many forms, including those that are financial (a paycheck), competitive (a blue ribbon) or social (someone else's approval or favor) in nature. Extrinsic motivation is less connected to who we are as people. Clearly, it has the power to compel us to do things we don't particularly enjoy or want to do. But it isn't always a bad thing. Sometimes, extrinsic forms of motivation can supply us with the extra energy we need to make great achievements.

Passion sustains creative thinkers through periods of difficulty and frustration.

The fact is that we are typically motivated by both intrinsic and extrinsic forces to think creatively. To ensure the best outcomes, the trick is to know how to keep your motivations properly balanced.

What difference can the right motivation make? Consider a Major League Baseball star that plays for fifteen seasons and makes millions of dollars a year, not counting all of his endorsement deals. He started playing the game when he was five years old and baseball was always his first love. Then one day, unexpectedly, he steps up to the microphone in a crowded press room and announces his retirement. “I'm just not having fun anymore,” he tells reporters. Just like that, his career ends. What happened? He loved baseball. But his love of the game (intrinsic motivation) was gradually overtaken by something else, perhaps money or fame (extrinsic motivation). Creative performance, like athletic performance, can also suffer the same fate.

Extrinsic motivation isn't inherently bad, as long as intrinsic motivation is primary.

Years ago, it was believed that any extrinsic motivation undermined creativity. Today, most scholars agree that extrinsic motivation isn't inherently bad, but it cannot outweigh a person's intrinsic motivation to engage in a creative task. Intrinsic motivation must be primary. But if a product of your own creative thinking (a short story, a new gadget, an ad) wins an award or someone pays you for it, it's okay as long as you don't become preoccupied with those rewards.

That's a liberating idea, given the fact that so many people think creatively as part of their job descriptions. It also reminds us that creative thinking — engaging one's creative process — isn't just a solitary activity. Remember, the usefulness of an idea is part of what makes it creative, and the people around us help make that evaluation. Even though the creative process is richly experienced on a personal level, creativity is also a decidedly social phenomenon.

The Componential Model of Creativity

Teresa Amabile, whom we've already cited in this chapter, is a pioneer in the development of what she calls a “social psychology of creativity.” While she acknowledges the value of studying creative thinking on an individual level, she points out the lack of research examining social influences on creative performance. Workplace and school environments where creativity is valued, she argues, can make changes that will help people be more creatively productive.

If a product of your own creative thinking wins an award or someone pays you for it, it's okay as long as you don't become preoccupied with those rewards.

Amabile's work, however, effectively bridges the gap between the scholarship on personal creativity and how it operates in social contexts. Her own Componential Model of Creativity proposes that three factors are necessary for creativity to occur in any domain (a social environment):

-

domain-relevant skills

-

creativity-relevant processes

-

intrinsic motivation for the task

We've already described each of these components and the importance of each to creative productivity should be clear. You'll note, however, that extrinsic motivation is not listed here as a necessary factor. The reason, of course, is because it simply can't be the primary motivation for creative performance. Extrinsic motivators may be everywhere in businesses and schools, but creativity can happen without them. Intrinsic motivation is what's essential.

Students sometimes ask how they can know for sure that advertising is the right career for them. Based on our own experience and what our former students tell us, here's the answer: Advertising is right for you if you believe solving problems with words and images and art and culture sounds like fascinating work that will make you happy. What's the message? First, happiness matters. Loving what you do makes your whole life better (intrinsic motivation is primary). Second, this business isn't for everyone. Most ad folks work ridiculously long hours and don't make a lot of money or get a lot of glory (extrinsic motivation is secondary). It's tough to be creative every day, on demand, to make someone else rich. If you're doing this kind of work, you'd better be having fun doing it!

UNDERSTANDING ADVERTISING CREATIVITY

As we've noted, creativity is relatively new as a topic in psychological research. Additionally, the teaching and study of advertising as an academic discipline didn't really begin until the 1970s. Given those circumstances, our understanding of advertising creativity is still developing. Because it's difficult to observe the creative process itself, most advertising scholars interested in this area have conducted research dealing with related topics. Take a look at the subjects of some of the most cited research papers in our field relating to creativity:

defining the creative concept

defining the creative concept

risk and creativity

risk and creativity

external evaluations and self-perceptions of creativity

external evaluations and self-perceptions of creativity

effects of training on idea-generation

effects of training on idea-generation

motivation for creative hobbies

motivation for creative hobbies

managerial control of creativity

managerial control of creativity

creative directors' views on education

creative directors' views on education

teaching creativity in the undergraduate curriculum

teaching creativity in the undergraduate curriculum

The existing research offers some wonderful insights and represents a broad curiosity about advertising creativity, how it operates, how it is facilitated and how it can be taught. However, we need to do more research that will offer a clearer understanding of the cognitive (read: thinking) dimension. How does the creative process look in the domain of advertising? How do our creative professionals develop ideas? These are important questions that remain largely unanswered.

Setting a New Agenda

For years now, we've been inspired by a 1995 study by Arthur J. Kover, emeritus professor of marketing at Fordham University. Kover conducted in-depth interviews with fourteen professional advertising writers and asked them to talk about their creative process. This was groundbreaking work. Many of Kover's colleagues didn't believe that the subjects of his study would be able to express their process in words and others questioned whether or not there was an actual process involved with their work in the first place. In spite of these warnings, the study proceeded and it yielded fascinating results. The writers whom Kover interviewed were quite capable of discussing their creative process and did so with great insight and detail. These professionals were thoughtful and reflective about their work. They seemed to possess a keen understanding of their own minds. They held what Kover called “implicit theories” (personal theories about how they did their work), and many of these were similar across interviews. Insights derived from this exploratory study immediately began to reshape our understanding of and appreciation for a creative process adapted to our industry. Kover's work also taught us that, in fact, one can observe and analyze thinking via the collection of first-person, retrospective accounts. He started the methodological ball rolling.

New Models of the Creative Process in Advertising

Emboldened by the knowledge that creative thinking could be studied in this manner, a new study was launched, this time focusing on advertising students learning to become art directors and writers. Glenn Griffin (co-author of this book) wanted to know more about these students' creative process and whether or not their training influenced any change in that process.

In this study, forty-four students at two different universities were each asked to create an ad and to be interviewed two weeks later with their finished ad in hand. During the one-on-one interview sessions, each student was asked to recount the experience of creating the ad. As Kover had already discovered among the professionals who participated in his study, the students were remarkably insightful, articulate and detailed in their descriptions of the process they engaged in to develop the ad. Griffin also observed broad similarities across the students' narratives, which would prove helpful in characterizing the shared elements of their process.

Half of the students interviewed were classified as “beginners” (they had just started their training), and the other half were considered “advanced” (they were preparing to graduate). Because the interviews were conducted with students at different stages in their training, their descriptions of creative process would be compared and any important differences analyzed.

The findings of Griffin's study, published in the Journal of Advertising, offered strong evidence that the students' creative process was meaningfully changed as a result of their training, supporting the idea that creative ability can be nurtured and developed. Two new models of the creative process, as experienced by advertising students, were also proposed: The Performance Model (the creative process at the “beginner” level) and the Mastery Model (the creative process at the “advanced” level).

The Performance Model of the creative process.

As beginners, aspiring art directors and writers think of themselves as problem solvers. They like to be given a problem and immediately begin working on solutions. They're learning to use thinking tools as a way to be more mentally productive, but they know and use only a few of them. They make notes and may scribble drawings while thinking — an activity we call “mindscribing.” However, they're likely to record only those ideas that they consider potentially viable. “Bad” ideas are typically not written down. The beginners' creative perspective is rooted in advertising. They see themselves as “makers of ads” and their solutions (the ads they create) tend to look and sound like advertising we've all seen before.

In contrast to their less experienced counterparts, advanced students are far less likely to accept a problem as it is presented to them. Instead, they prefer to think about a problem for a while and often decide to redefine the existing problem or find a new one that confronts the client. As they approach the end of their training, advanced students have learned many thinking tools and are more experienced and extensive users of them. They've also come to understand which tools are most useful to them as individuals. They make lots of notes in their journals while thinking; their mindscribing is unfiltered. Notes and sketches are made without prejudgment of their viability. The advanced students see themselves as “idea people,” and they are typically more concerned about the creative quality of an idea than how it will translate into an ad. The idea, instead of the ad, is considered the most important product of thinking. However, once the ad is created, it tends to reflect a more original approach than that of a beginner.

The Mastery Model of the creative process.

The Performance and Mastery Models, in addition to identifying key dimensions of the advertising creative process as it is developed, raise the following points:

-

It appears that advertising students, over the course of training, are encouraged to become critical thinkers and to make sure that the problem presented to them is the most important one to solve.

-

The acquisition of thinking tools is an important factor in the development of an advertising student's creative process. Individuals test these tools and decide which are the most productive for them.

-

Advertising students learn to stop prejudging their own ideas during the process and keep better notes over time. They come to understand that a viable idea can live anywhere.

-

With experience, advertising students begin to consider the discovery of a great idea (instead of a finished ad) as their ultimate goal. Translation of that idea into an ad is a secondary goal.

Of course, no theoretical model will offer a complete picture of the phenomenon it's intended to describe. However, understanding more about how art directors and writers develop their process is helpful if we intend to study the creative process of their professional counterparts.

WHERE WE'VE BEEN AND WHERE WE'RE GOING

Creativity can be magical, but it isn't magic. It's a method for finding solutions to problems — solutions that reveal our ability to adapt and advance as human beings. And here's the best part: Everyone has the potential to be creative.

People are still learning about the creative process. There's general agreement about how it works in stages and that it operates at both individual and social levels. The process can look different depending on the domain (or line of work) where it happens. Creativity is an act of will that is fueled by passion. It isn't the easiest topic to study. But creative thinkers among us, true to form, are finding ways to tackle it.

The creative process is so crucial to everything we do in advertising (as educators and professionals), but we spend far more time looking at ads than we do thinking about how they were born. We know a little bit about how our students access and develop their creativity because that's where we live. Our next step is to tap the brains of creative pros who do this work and to learn from them. They have so much to share with us.

We're glad you're interested in joining us on this journey. Let's get started.