THE PITHEKOUSSAI WINE CUP marks the limits of the written Homer. It is the edge of a time-cliff: step beyond it, further back in time, and the ground falls away. In that disturbingly airy and insubstantial world out beyond the cliff face, before the eighth century BC, Homer is unwritten, existing only in the minds of those who knew him.

It is a disorientating condition for our modern culture: how can something of such importance and richness have had no material form? How can the Greeks have trusted so completely to their minds? At home in Scotland, I sometimes go up to the edge of the sea-cliff above the house, looking down to the fulmars circling in the four hundred feet of air below me. Again and again, the birds cut their effortless discs in that space, turning in perfect, repetitive circles, in and out of the sunlight, scarcely adjusting a feather to the eddies, but calm and self-possessed in all the mutability around them; and I have thought that in that fulmar-flight there may be a model of the Homeric frame of mind. You don’t need to fix something to know it. You know it by doing it again and again, never quite the same, never quite differently. You may even find, in that tiller-tweaking mobility – a slight adjustment here, another there – that you know things which the rigid and the fixed could never hope to know. The flight is alive in the flying, not in any record of it. And perhaps we, not Homer, are the aberration. Of about three thousand languages spoken today, seventy-eight have a written literature. The rest exist in the mind and the mouth. Language – man – is essentially oral.

Until the twentieth century, no one had any idea that Homer might have existed in this strange and immaterial form. It was the assumption that Homer, like other poets, wrote his poetry. Virgil, Dante and Milton were merely following in his footsteps. The only debate was over why these written poems were in places written so badly. Why had he not written them better? Both the Iliad and the Odyssey are riddled with internal contradictions. No self-respecting poet would allow such clumsiness.

The great eighteenth-century Cambridge scholar Richard Bentley – the dullest man alive, according to Alexander Pope, ‘that microscope of Wit,/Sees hairs and pores, examines bit by bit’ – thought that Homer wrote

a sequel of songs and Rhapsodies, to be sung by himself for small earnings and good cheer, at festivals and other days of Merriment; the Ilias he made for the men and the Odysseis for the other Sex. These loose songs were not connected together in the form of an epic poem till … about 500 years after.

Homer was no longer a genius; he was the work of an editor-collector, perhaps not entirely unlike Professor Bentley himself. Later microscopes of wit thought there was not even one author, but a string of minor folk poets whose efforts had been brought together by the great Athenian or even Alexandrian editor-scholars. The Prince of Poets had been dethroned. The scholars had won. And so the nineteenth century was animated by the debates between Analysts and Unitarians, those who thought Homer had been many and those who continued to maintain that he was one great genius.

The argument lasted for over a century, largely because of the sense of vertigo a multiple Homer induced. If Homer was dissolved into a sequence of folk-poets, one of the greatest monuments of Western civilisation no longer existed. Nevertheless, these were the preconditions for the great discoveries about Homer made in the early twentieth century by the most brilliant man ever to have loved him.

Milman Parry is a god of Homer studies. No one else has made Homeric realities quite so disturbingly clear. Photographs show what his contemporaries described, a taut, focused head, a man ‘quiet in manner, incisive in speech, intense in everything he did’. There was nothing precious or elitist about him, and his life and mind ranged widely. For a year he was a poultry farmer. Along with the technicians at the Sound Specialties Company of Waterbury, Connecticut, he was the first to develop recording apparatus which didn’t have to be interrupted every four minutes to change the disc. He took his wife and children with him on his great recording adventures in the Balkans, and at night sang songs to them which mimicked and drew on the epic poems he had heard in the day. At Harvard, where he became an assistant professor, he took to washing his huge white dogs in the main drinking-water reservoir for the city, stalking about the campus in a large black hat with ‘an aura of the Latin quarter’ about him, regaling his students with the poetry of Laforgue, Apollinaire, Eliot and e.e. cummings. Supremely multilingual, at home in Serbo-Croat, writing his first articles and papers on Homer in French, this was the man who pulled Homer back from its academic desert into life.

Milman Parry, 1902-35

Parry was born in June 1902, and brought up a Quaker in the sunny sterilities of Oakland, California. From that clean, germ-free youth he plunged off into ancient Greek at Berkeley, and when still there, writing the thesis for his Master’s degree, jumped to the idea that Homer was neither a great poet making these poems from nothing, nor a collection of minor folk-tales somehow strung together, but the combination and fusion of those two ideas: a poet working within a great tradition which had deep roots and multiple sources. The poems were composed by a man standing at the top of a human pyramid. He could not have stood there without the pyramid beneath him, and the pyramid consisted not only of the earlier poets in the tradition, but their audiences too, the whole set of assumptions and expectations in which the poems swam. Homer, a plural noun, were the frozen and preserved words of an entire culture. At different moments in their evolution, the songs would have sounded different, but there is no need to assume that they would have been cruder or worse. At any one moment the singer is standing on the human pyramid beneath him. Hear them as they should be heard and you will have the sound and meanings of the distant past in your mind and ear.

Parry was a romantic, who loved the ancientness of the past for itself and for its stark difference from twentieth-century America. The motivations apparent in Keats are in Parry too. For the classical scholars of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, brought up in an elite and aristocratic culture, Homer may have seemed like a contemporary, his words on honour and self-sacrifice to be taken as relevant instructions for the noble life. The only task was to clean Homer up, to make Homer more like them, to classicise him, to rid him of his repetitiveness and his awkward lack of savoir faire, to translate him, as Pope had done, with many delightful felicities overlying the raw Greek.

For the brilliant young American from Oakland, that could never have been the starting point. Homer for Parry is almost unapproachably strange and distant. Only by recognising that distance could he be understood. Parry’s guiding light was Ernest Renan, the star of the dinners at the Repas Magny. Renan had insisted on understanding the past on its own terms. ‘How can we grasp the physiognomy and the originality of an early literature,’ he had written,

if we do not enter the personal and moral life of the people who made it, unless we place ourselves at the very point in humanity which was theirs, so that we see and feel as they saw and felt; unless we watch them live, or better, unless for a moment we live with them?

This liberal, anthropological understanding of what Homer might be – quoted and requoted by Parry in his papers – was far ahead of anything other Anglo-Saxons were thinking, and the key to that penetration of the past was in the nature of the verses themselves. Parry’s central question was this: what does the nature of the poetry say about the world in which it was composed? He focused on two qualities: the way in which heroes and objects are accompanied by almost unvarying and sometimes inappropriate adjectives and epithets, the building blocks of unvarying ‘formulae’; and the role of words in Homer which ‘Homer’ – the eighth-century BC scribe who wrote the poems down – almost certainly did not understand.

Parry was told by the Classics faculty at Berkeley in 1922 that there was no chance he would get a doctorate by following up on his Master’s thesis on the formulae in Homer. It was not what an American classicist did. For a year Parry worked with his chickens, but he recognised that his future studies would find most encouragement with the anthropologists in Paris, and when he was twenty-two he went there to do his doctorate at the Sorbonne. What he set out to analyse may seem arcane, but it is in fact a route into the mind of the Bronze Age, an archaeology of the word. First, abandon any idea of the classic poet. The poems are not objects conceived by a single, gifted person, but profoundly inherited, shaped and reshaped by a preceding culture, stretching far back in time, something as much formed by tradition as the making of pots or the decoration of their surfaces. Homer is the world of tradition-shaped poetry, not of realism, as unlike reality as opera and profoundly guided by its own conventions. And the governing fact in that epic world is the music of the poetry.

The Homeric epics are essentially the music of hexameters, a Greek word that means ‘six measures’, because in each line there are six ‘feet’ for which the words must be chosen to fit the pre-existing pattern. This verse is measured language. Within each of the six feet, the language can fall in different ways. Feet made up of a long and two shorts (a phrase like ‘This is the’) are called dactyls, after the Greek word for a finger, daktylos, a word which both mimics the shape of the human finger – a long bone followed by two short ones – and is a dactyl itself. A foot of two longs (‘hemlocks’) is a spondee, the Greek word for a libation, an offering poured out with certainty and directness for a god, and which is a spondee itself. Most feet can be either dactyls or spondees, but the rules of epic insist that the fifth foot is usually a dactyl (‘pines and the’) and the final foot always a spondee. Here, with those rules in mind, is an English hexameter, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

Variation is always to hand: the dactylic ‘murmuring’ could be the spondaic ‘moss-girt’. The pines have to be surrounded by hemlocks because dactylic ‘rivulets’ would not be allowed at the end of the line, but Longfellow could have chosen the spondaic ‘wood prim-eval’, to make an even weightier line,

But he may have felt that the breeze was not blowing through that American landscape quite as he wanted. Flexibility within the pattern is at the core of the system. This is not an iron prison but a means of making memorable music, of allowing music to carry a tale.

Each of the lines has a natural break (marked here by ^ after ‘primeval’) called a caesura, and the line naturally falls into two halves on either side of it. In reality there are many variations in Homeric verse, but this is the underlying structure, a combination of variety and rhythmic certainty, governing the way each line develops. It is the sound of epic, entirely unlike the way anyone would ever have spoken, but embodying for the Greeks the heroic world.

Parry established that an astonishingly high proportion of the poems composed in this rhythmically repetitive form was made up of pre-fabricated elements which had been evolved to fit the metrical pattern of the hexameter. Anyone telling the story of the Odyssey or the Iliad in verse would have had, ready to hand, words and expressions which could easily be put into this form. Just under a third of all the lines in Homer are like this, either repeated entirely or containing phrases repeated elsewhere.fn1 Saying the same thing, or a version of the same thing, over and over again, lay at the foundations of the Homeric world.

If Alexander Pope in eighteenth-century England thought the excellence of poetry lay in ‘What oft was thought/But ne’er so well express’d’, Homer’s ideal is precisely the opposite: saying the true things in ways that are deeply familiar: what oft was thought and almost always expressed in exactly the same way. Homer, in its genes, was set against newness, turning to the fixed music of the hexameters and the phrases inherited from the past for the validation of its truths. This is poetry which can be thought of in the same light as weaving patterned cloth or building wooden ships. The past, through endless tests, successes and failures, has come up with ways of using and joining materials that work, that are robust, reliable and true, that can cope with seas or storms at night, that have a grace and commodity about them, whose threads can glitter in the candlelight and which are, of their essence, inherited.

Nowhere is the formulaic method of the verse clearer than in the way Homer uses the name of a hero or god, attached to a descriptive adjective or phrase, to fill in the second half of a hexameter, the space between the mid-line break, the caesura, and the end of the line. You can represent the gap Homer needed to fill again and again by the phrase ‘old man chewing a beanstalk’. Each of the thirty-seven most important heroes and gods of the Iliad and the Odyssey has a formula attached to his or her name which exactly fills that gap. One after another they queue up to occupy it: polytlas dios Odysseus – much-suffering godlike Odysseus is there thirty-eight times; followed closely by podarkēs dios Achilleus, swift-footed godlike Achilles; boöpis potnia Hera, cow-eyed goddess Hera; thea glaukopis Athene, goddess owl-eyed Athene; anax andron Agamemnon, lord of men Agamemnon – and so on through the whole cast. Equally formulaic phrases often fill the other part of the line – ‘and so in reply he spoke’, ‘and so she said when smiling’ – so that entire lines, and entire sequences of lines, are filled up not with words chosen for their individual strength, poignancy or relevance, but as a means of keeping the music constant, keeping the characters present and alive in the surface of the poem.

Once you grasp this core repetitive mechanism – often obscured in translations of Homer – these poems become profoundly strange, sinking back away from us in time and mentality, to a point where story and character are visible only though the mask of the formulaic, as unreal as a Noh-play, as mysterious as an unheard liturgy. The stories of the warriors at Troy and the wanderings of Odysseus become as alien as a tale told in hieroglyphs or cuneiform. This is the Renan effect, seeing the past for its strangeness, not imposing our own clarity or suppositions on something from the other end of human consciousness.

was not one in which a poet must use his own words and try [as] best he might to utilize the possibilities of the metre. It was a poetry which for centuries had accumulated all such possibilities – all the turns of language, all the words, phrases, and effects of position, which had pleased the race.

So powerful was the need to keep the music whole, that these metrically convenient phrases are often used even when they make no sense. The heavens are ‘starry’ in the middle of the day; linen is ‘gleaming’ when it is about to be washed; Odysseus is called ‘much-suffering godlike Odysseus’ by the shade of a man he has recently killed, now in Hades; Aegisthus, the adulterous lover of Clytemnestra and murderer of Agamemnon, is ‘blameless’; ships are ‘swift’ when they have been turned to stone. But the hexameters roll on, sustained by these formulaic expressions, a music whose sense of its own overarching greatness matters more than any local meaning. By the time of ‘Homer’ – often put in quotes by Parry – the heroic epithets had become virtually meaningless. Achilles was not really ‘swift-footed’ when lurking in his tent for book after book of the Iliad, refusing to fight for the Greeks; Odysseus was not really ‘suffering much’ when performing as only one among many of the Greek commanders at Troy. These words, in Parry’s analysis, had become useful line-fillers because that is what the music of the hexameters, the tradition itself, required. They had nothing to do with what the poem meant.

This was a radical dismantling of the inherited Homer. Ever since the Alexandrians, Europe had tried to rescue Homer from his own errors. Parry, alive with all the early twentieth century’s fascination with the strange truths to be found in non-Enlightenment cultures, now plunged him back into a deeply pre-classic world, taking him apart in the process. Parry was accused of being the ‘Darwin of Homeric scholarship’, the man who had turned a god into an ape. But he is more like Homer’s Gauguin or Stravinsky, creating a poet for a Jungian world, allowing for the validity of his pre-rational methods, finding there beauty which the classic tradition was blind to and wished to excise. Parry thought Homer beautiful in the way an African totem or a Polynesian mask might be beautiful. Europeans since the Renaissance might have looked on Homer as one of the furnishings of the gentlemanly life. Parry saw himself as no part of that tradition, and for him distance and inaccessibility stood at the root of Homer’s meaning.

Parry had summoned a strange and troubling Homer from the depths, a poet entranced by his inheritance, almost blind in front of it, spooling out what the past had given him, ‘a machine of memory with limited aesthetic scope’, as the Californian critic James L. Porter has described him, ‘his materials emerging from the deepest lava flows of epic time’. This is Homer as Hawaiian volcano, oozing the past like the juice from the earth’s mantle. Parry even suggested that the poems were full of words, often in old forms of Greek, that may have fitted the music of the hexameters but which ‘Homer’, the Ionic poet from Chios in the eighth century BC, did not himself understand. There are 201 words in the Iliad and the Odyssey which occur only once in Homer and never again in the whole of Greek literature. That number goes up to 494 if you include proper names, their roots deep in ancient forms of Greek, many of them spoken in Thessaly in northern Greece, but which in Chios and through the Ionic fringe of Anatolia were no longer used. Many have never been translated – unintelligible to the Greeks of fifth-century Athens or third-century Alexandria, their meaning still now only to be guessed at.

But for Parry, this was all evidence of the tradition at work, of Homer being more interested in epic music than its meaning. The past must be given its due, and one aspect of that past was the unintelligibility of its language. Only then would you understand the relationship of the singer and his tradition: ‘The tradition is of course only the sum of such singers. One might symbolize it by the idea of a singer who is at once all singers.’ He quoted Aristotle’s Rhetoric on the ideal for an epic poet: ‘One’s style should be unlike that of ordinary language, for if it has the quality of remoteness, it will cause wonder and wonder is pleasant.’ Mystery is power, and the not-entirely-understood seems greater than what is clear. Parry’s vision of Homer is very nearly like the unintelligible ritual of the Latin mass sung to uncomprehending peasants across medieval Europe: words which were meaningful because they could not be understood. Eliot’s passing thought in his 1929 essay on Dante that ‘genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood’ is less radical than this. Parry sees Homer as a culture riding into the future on poetry whose deepest parts are entirely inaccessible.

His professors at the Sorbonne told him something which he hadn’t quite grasped: everything he had been pursuing was a sign that Homer was not originally a written but an oral text. This formulaic composition was the mark of a sung poem, so dependent on pre-shaped elements that a singer could compose it as he performed it. Such songs were neither monstrous feats of memory nor improvisations, invented from one moment to the next, but tales told with the help of ancient formulae, devised long before, which the singer could rely on as steady metrical elements in his lines. He did not have to learn any poems, but he had to learn what the tradition could teach him, the ability to make poems on the hoof.

This may seem a presumptuous comparison, but it is clear to me that anyone who has ever stood up in front of an audience, of any kind, and made a speech, knows what is meant by composition-in-performance, particularly if you have made the speech before, or over the course of a few months have the chance of making it a few times to different audiences, in different atmospheres and for different purposes. You know, in essence, the stories you have to tell, the morals you would like to draw. You know the moments where pathos is available and those where people will laugh. You know what has worked before and what has died as it left your lips. You know, above all, but just how you know is difficult to know, how to establish a kind of gut-dialogue between you and the audience, to feel them feeling what you are saying, to understand point by point what might be the right development of the tale.

It is not improvisation, because you know at least where you might be going. You have your formulae, conscious, semi-conscious, unconscious, the tics that make you who you are, that are your inheritance. You have passages that run in familiar ways, that allow the intuition to consider the shape of what you are making, the way you might go next, the goal it must aim for. And you have your ingredients, your set terms, the passages where you need not invent, where you can say what has been said before, and those passages where invention seems to come easily to the mind, not in the sense of making up a new substance for the story, but in finding words that will work for it. All this is easier when there is some darkness in the room.

This is not to say that I speak in hexameters, or devise complex reflective schemes and ironies, that I keep in train a thousand characters over 14,000 lines. But at a very basic level I understand that between memory, the present moment and the spoken word, is a kind of three-part dance. When my children were small, we used to play this Homeric game. Last thing at night, I would tell them long rhythmic poems about our lives and our holidays, the little adventures we had in boats or trains, all designed to send them to sleep. Nothing was repeated more often than the story of taking the night train to Scotland, feeding off the atmosphere of excitement and anticipation we got from it every summer and Christmas. The poem was never quite the same from one telling to the next, but it used all the easy techniques of repetitive phrasing and a thumping rhythm which, as Milman Parry said of his own story-telling to his children when they came with him to Bosnia, are the overused recourse of the bad epic poet and almost untouched by the good.

But this is epic verse as it is made today in England, in the evening, upstairs in the bedroom, traditional, formulaic, with lumps of the culture embedded in it, full of memories, lullingly soporific. I never wrote anything down at the time, and I have written this now straight on to the keyboard as it came to mind, nothing predetermined, except the formulae and the memory of having done something like it often before:

That was the night and it was very very dark

That the children found their way to the station

and there at the station waiting in the dark

was the long long train that they knew from before.

Dark was the train and wonderfully shiny

the lights from the station shining on its flanks

and the lights in the cabins glowing inside

and there as the children stood in the station

watching the train that was dark in the night

they said to each other Can we climb aboard?

Can we find our way to our beds in the train?

And their father said No to them, No not yet.

Wait till the guard opens the doors.

So they stood in the cold and longed for the warmth

Of the long night train as it made its way north.

Together they stood and huddled in the dark

Waiting for the moment when the doors might open

and then at last they heard far away

The banging of doors and the shouting of men

as each of the guards got out his big key

and opened the doors for the night to begin.

I usually fell asleep before they did, lulled by my own pump-engine rhythm, but this is Homeric in its parataxis, its telling of the story with no subordinate clauses, accumulating one detail after another, its rapidity, its formulaic phrases taking up reliable positions in the pattern of the lines, its cherishing of memories and heroising of the ordinary, its love of the shared experience between speaker and listener, its cavalier way with facts.

What can you say? Only that this sort of rhythmic, inherited story-telling is part of the human organism, and that the world in which the Iliad and the Odyssey began was an outgrowth and fulfilment of this basic capacity, one in which the telling of your own great tales was not something done by a father at bedtime but in the gathering of people for whom these stories were the foundation of their lives, the thing that might last when everything else might not.

Between 1933 and 1935, prompted by his Parisian professors, Parry made his journeys through the remote mountain villages of Yugoslavia. It was quite a caravan: his assistant, a Harvard student, Albert Lord, several typists and interpreters, and Nikola Vujnović, a singer himself from Herzegovina, who would ease the way with the people they met. They met and listened to over seven hundred singers, each with their gusle, the single-stringed violin that accompanied the words. Almost 13,000 separate songs were written into eight hundred notebooks, and hundreds more recorded on 3,500 twelve-inch aluminium discs. When he returned to Harvard, Parry delivered to the library almost exactly a ton of archive material.

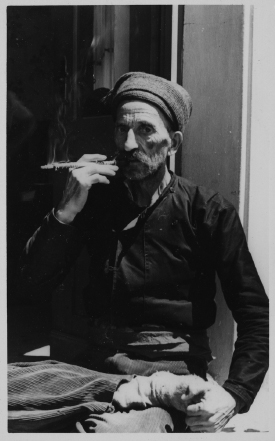

Bégan Lyútsa Nikshitch, a Turkish bard from Montenegro, ‘a tall, lean and impressive person’.

The excitement was real. Here was the past made flesh and blood, stubble and cigarettes, sawing out its epics in front of them. On market day they would drop in at a coffee house and make enquiries. Were there any guslari nearby? Were they good? Could they come? One morning at Bijelo Polje, a small town in the hills of northern Montenegro, they found, lying on a bench in a coffee house, a Turk smoking a cigarette with an antique silver cigarette holder. He was Bégan Lyútsa Nikshitch, ‘a tall, lean and impressive person’ who spoke to them like a warrior from the depths of the past.

Bégan knew a certain Avdo Medjédović, a peasant farmer who lived an hour away, and he was insistent that the Americans had to hear him.

Finally Avdo came, and he sang for us … We listened with increasing interest to this short homely farmer, whose throat was disfigured by a large goiter. He sat cross-legged on the bench, sawing the gusle, swaying in rhythm with the music. He sang very fast, sometimes deserting the melody, and while the bow went lightly back and forth over the string, he recited the verses at top speed. A crowd gathered. A card game, played by some of the modern young men of the town, noisily kept on, but was finally broken up.

The next few days were a revelation. Avdo’s songs were longer and finer than any we had heard before. He could prolong one for days, and some of them reached fifteen or sixteen thousand lines. Other singers came, but none could equal Avdo, our Yugoslav Homer.

The guslari always sang their long epic songs of battle and disaster with a kind of hard energy, loud, at a high pitch, the singer’s whole frame gripped with the effort. This was no smooth crooning but a passionate engagement of mind and body.

It takes the full strength of the man to sing in this way. The movement of the body in playing the instrument, the laboring of the lungs needed for the breath needed for the volume of song, the strain on the muscles of the throat and mouth that go to forming the words, make the singing a toil, and a good singer after a half hour of his song is drenched in sweat.

Nothing about the sound of the gusle is charming, and the way in which the poems are sung has little apparent melody. The string of the instrument screeches from one line to the next, the guslar chants his lines without any attempt at a flourish or grace notes. This is not an exhibitionist performance. It is more serious than that, the voice of concentration, as he composes with his formulaic phrases and passages, the metre heavily emphasised in every phrase he uses. It is the words that matter, their recounting of tragedy and suffering. But the unbroken presence of the instrument is there not for its tune but for its strangeness, the signal it makes that this is another world.

Each singer sang usually for between twenty and forty minutes, sawing away at the gusle on his lap, singing up to twenty lines of his song every minute, more slowly at first, speeding up as he reached the crisis of the tale, and then stopping for a cup of coffee, a cigarette, a glass of burningly fierce plum raki and a visit to the loo. They didn’t always get to the end of their song before the session tailed off into the night. Some singers did not even know the endings of their songs, and when they did come to the last part, they were always more various than the beginnings.

In June 1935 Halil Bajgorić, a thirty-nine-year-old stockman from a remote mountain village in Bosnia, sang them a long song about a young and resourceful hero, called ‘The Wedding of Mustajbey’s Son Bećirbey’. Even as he began, after a thirty-second introduction on the gusle alone, setting the rhythm, establishing the metre in his mind, it was clear that Bajgorić’s tale was driven along by the formulaic pattern, not only at the level of individual phrases, but in the shape of scene after scene.

Bajgorić’s epic is simple, but it shares many things with Homer. First, as in Homer, the adventure begins with the break of day and the waking of the hero:

Oj! Djerdelez Alija arose early,

Ej! Alija, the tsar’s hero,

Near Visoko above Sarajevo,

Before dawn and the white day

Even two full hours before dawn,

When day breaks and the sun rises

And the morning star shows its face.

In epic, it is not enough to say ‘One morning …’. It needs expansion, space opening out around the story, the luxury of time expanding around the singer. And it can joke about that need for a little more time:

When the young man got himself up,

He kindled a fire in the hearth

And on the fire he put his coffee pot;

After Alija brewed the coffee,

One, then two cups he poured himself –

One, then two, he felt no spark,

Three, then four, the spark then seized him,

Seven, then eight, until he had enough.

Finally, the hero sufficiently stoked with caffeine, the formulaic sequence can begin: the preparation of ‘a long-maned bay horse’ for the journey, the horse made beautiful with all her trappings, ‘Like a careless young shepherdess up on a mountain/Clothed in her hood and motley jacket’, the fitting of the hero with his beautiful equipment, his swords and daggers, his elegant pistols, one from Venice, one from England, to the point where he can set out on his journey, swim a great river while still mounted on his precious mare – she knows what he wants without him saying so – until at last he arrives at the city where

He quenched his thirst with dark red wine

And he smoked two pipefuls of tobacco.

Translate the Homeric situation to the valleys of early-twentieth-century mountain Europe and the poem translates itself. That is Parry’s point: this poetry was the product not of unique glowing genius, but of a world in which the spoken epic is the vehicle which carries the meanings of the past into the present, and in which the need to tell the poem again and again is itself the most powerful force in its shaping. Formulaic verse is a response to social need.

Parry was entranced by the world he had stumbled on. ‘The moment he cherished most,’ his student Albert Lord wrote later,

occurred toward the end of one of his earliest days in the Serbian hills, during the summer of 1933. They had settled at an inland village and at length come across a gouslar, the first epic poet Parry had ever known, an old man who claimed to have been a warrior in youth and to have cut off six heads. All afternoon he sang to them about his battles. At sunset he put down his gousle and they made him repeat a number of his verses. Parry, very tired, sat munching an apple and watching the singer’s grizzled head and dirty neck bob up and down over the shoulder of Nikola, the Herzegovinan scribe, in a last ray of sunlight. ‘I suppose,’ he would say, in recalling the incident, with crisp voice and half-closed eyes, ‘that was the closest I ever got to Homer.’

It is as powerful a moment in the history of Homeric understanding as the evening when Keats and Cowden Clarke peered into Chapman’s Homer, or when Carl Blegen in the summer of 1939 found the smashed fresco of the singer, destroyed in the fire three thousand years before. Parry, listening to these men and their grating instruments, their sawing voices, heard in them the transmission of epic across the generations, the thousands of years. It was the moment in which the vacuum of life before the written word had suddenly acquired a substance.

Through Nikola Vujnović, the Herzegovinian singer, Parry asked Halil Bajgorić where he had learned his songs. All came from his father, he said. But how had he actually learned to sing and play when he was a young boy? Halil described how he would sneak the gusle away from his father, and in another room, when his father was sleeping, he would sing a little.

Nikola: But why did you feel the need to sneak the gusle away from him?

Halil: Because I wanted to know how [to play], I saw there was a place for him among the people because he knew how to sing. He’d come there, when there were gatherings among us, when there were weddings, some celebrations, and I’d go with him. And he’d come there, and there would be a lot of people, and the people all made room and said, ‘Singer, come on up to the front and sit by the man brewing coffee.’

Nikola: Aha.

Halil: Then, by God, I too wanted to learn to play the gusle.

This is how it must always have been: the father at the centre of the listening circle, the boy on the edge of it seeing his father in a different light from the usual man at home with his breakfast, the current of the heroic recognised by the boy, the stirring of ambition to have that scale of existence in his own life, the tentative beginnings in secret, his imagining of the audience, his first attempts in public, the increasing confidence with which the formulae might become his own, that miraculous sensation when he felt he could divert the stream through his own life and mind.

‘The verses and the themes of the traditional song form a web in which the thought of the singer is completely enmeshed,’ Parry wrote later, establishing the primacy of the tradition over the individual poet. ‘The poetry stands beyond the single singer. He possesses it only at the instant of his song which is his to make or mar.’ ‘His to make or mar’ is the idea in the mind of the young Halil, practising with his father’s gusle in the hidden room.

They asked one singer called Ibrahim Bašić, known as Ibro, a seventy-year-old woodcutter from central Herzegovina, where he got the words for the songs. If he told a tale a second time, did he repeat it word for word? Yes, Ibro said, word for word.

Nikola: What is, let’s say, a word in a song? Give me a word from a song.

Ibro: Here’s one, let’s say, this is a word: ‘Mujo of Kladusha arose early,/At the top of the slender, well-made tower.’

Nikola: But these are lines.

Ibro: Well yes, but that’s how it is with us; it’s otherwise with you, but with us that’s how it’s said … But here’s one, let’s say this is a word: ‘Mujo of Kladusha arose early’ – that is a word for ‘arose early’; ‘Before dawn and the sun is arising’ – that’s also a word for ‘arose early’.

Words are not individual, separated lexical objects, but poetic lines, half-lines, formulae, metrical units and story units that can slot into the song. This is building a wall not brick by brick but panel by panel. Getting up with the dawn, preparing the chariot, arming the warrior, equipping the ship, rowing for the wind, swift-footed Achilles, much-suffering Odysseus: these are the words in which Homer speaks. To repeat a song ‘word for word’ is to choose any one of these formulae as they come to mind. The tradition is not a fixed object like the written text of Paradise Lost or the Aeneid; it is a braided stream of possibilities pouring into the present out of the past, essentially multiple, recomposed from its given elements every time it is sung, and in that retelling conceived of as remaining the same. It is a curiously Platonic conception of a story, as if the epic’s essence were in a pure, immaterial, pre-existent form, of which the actual words that are sung are an almost incidental bodying forth into our mundane reality. ‘Plato thought nature but a spume that plays/Upon a ghostly paradigm of things,’ Yeats said, and you could say the same of Parry’s Homer: Homer thought his poem but a spume that played upon the ghostly truths that came from long ago.

Parry was convinced that he had pushed the modern understanding of Homer back beyond the eighth-century BC horizon at which writing arrived in the Greek world. He thought he knew that in the formulaic composition-in-performance of the Yugoslav guslars he had heard the way in which the Iliad and the Odyssey had been composed. Homer was clearly the most extraordinary practitioner – the songs from the Balkan mountains were thin and empty compared to the Iliad and the Odyssey – but this was the practice of which Homer was the master. ‘The more I understand the South Slavic poetry and the nature of the unity of the oral poem,’ Parry wrote late in his life,

the clearer it seems to me that the Iliad and the Odyssey are very exactly, as we have them, each one of them the rounded and finished work of a single singer … I even figure to myself, just now, the moment when the author of the Odyssey sat and dictated his song, while another, with writing materials, wrote it down verse by verse, even in the way that our singers sit in the immobility of their thought, watching the motion of Nikola’s hand across the empty page, when it will tell them it is the instant for them to speak the next verse.

Parry had crossed the boundary into the mental world occupied by Homer. He was thirty-three when he returned in triumph to Harvard with his ton of notebooks and aluminium discs. A life’s work stretched ahead of him, but that December, on a visit to his mother-in-law in Los Angeles, he died in a stupid accident when a revolver mixed in with his clothes in a suitcase went off and killed him. Something resembling the book he was planning to write about Homer and the guslari was written much later by his assistant and student Albert Lord, after a long and fruitful career spent fulfilling the promise of the visionary man who had once led him to the Balkans.

A rainy early-autumn day in the Hebrides, the cloud down low over the islands, a sheen of wet on the grass. We have been gathering sheep for the September markets. The sea around us is bruised by the wind. Hardly a word has been spoken all morning, as the four of us have been strung out in a line across the hillside half a mile long, two or three hundred yards between each of us, our arms flailing at the gloomy and reluctant sheep. The sky is torn into shreds and patches. The only words have been the violent insults thrown at the dogs.

Now the lambs are down at last in the fank on the beach, ready to be taken off by dory and fishing boat tomorrow morning. The sheepdogs nip at them through the bars. The shepherds, Kennie, Nona and Toby, are all leaning on the hurdles of the fank and discussing the animals in front of us, their fleeces shrivelled and lank in the rain. They are not as good as anyone had hoped:

Nona: It was the wet spring that did it.

Toby: That was what kept them back.

Nona: Aye, and the dry summer.

Toby: Aye, that would have kept them back too.

Nona: And it’s been cold these last few weeks.

Toby: That wouldn’t have helped.

Nona: No, they are not as good as they might have been.

Toby: But there are some big ones in here.

Nona: Monsters some of them.

Toby: There’s some good lambs in there.

Nona: Look at that horned ewe with her twins.

Toby: There’s some very heavy lambs here.

Kennie: It’ll be heavy work getting them into the dory.

Toby: [To his dog] Come into heel, will you.

Nona: You are not going to get that quality every time.

Toby: No, not every time, that’s right.

Kennie: No, not every time. You can’t hope for it every time.

This was a chat, a break from work, with a roll-up and a cup of tea and caps on the backs of heads, but it is the talk that has been had since the Neolithic. Its buried musicality, the repetition of its phrases, the antiphonal give and take of each repeating gesture – all of that presses up under the surface of the words. Perhaps this is the natural way we have of speaking, just hesitating on the lip of the musical, but it is a quality of language which is usually shut down and denied in a written culture.

Parry’s new understanding of the Homeric poems undoubtedly pushed them into the pre-literate centuries before 800 BC. Homer comes from an oral and aural world, a world of public speech and shared listening. But how far back? And how much of that ancient world could survive in the telling and retelling? Can one really reach back through the words of Homer to that moment in about 1800 BC when the Greek-speaking people, whatever they were called, came south to the Mediterranean world of sailing ships and stone-walled cities?

There is a real difficulty: the reliability of these story-tellers. They inherited the past, they were conscious of that inheritance, but how much did they transform what they had been given? Milman Parry and his team asked the Serbian singers if their stories had any truth in them, a question, it soon became clear, which did not entirely make sense to them.

Ibrahim Bašić, the guslar known as Ibro, answered casually enough: everything in his songs was true, except for details he added to make them more fitting. His stories might have required heroic furniture – swords, horses – to sound right, but that didn’t make them any less ‘true’. It might even have made a story ‘truer’, more like the heroic past Ibro had in mind. These songs were epics, extensions of memory over deep reaches of time. They weren’t history. They celebrated a heroic ethos and their purpose was not to preserve events. They existed in the ‘now’, standing as a bridge between the present moment and the distant past.

There is one extraordinary discovery from Crete, made by the American-Greek scholar James Notopoulos, a follower of Parry and Lord, that relegated the question of historical truth in ancient epics to a category that was at least moot. Notopoulos was a professor in Hartford, Connecticut. His father had been a poor Greek immigrant from the Peloponnese who became rich by building and operating theatres in small-town Pennsylvania. At Oxford, James had become entranced by Homer and by Parry’s discoveries. An intense romantic, he was remembered by students gazing dreamily at the ceiling through clouds of pipe-smoke during Greek classes in Hartford. But he was also a precisionist, capable of ‘making the wince into an art-form’ when a pupil failed to pronounce the Greek properly or get the metre right.

In 1953, with a Guggenheim scholarship, Notopoulos travelled to the far west of Crete, one of the most heroic landscapes in Europe. In the wild and stony mountain province of Sfakia, gorges are sawn thousands of feet down into the barren, dry White Mountains. I have seen fences around sheepfolds there held up with the rusted barrels of old machine guns, and have sat eating my lunch in a café while at the table next to me a man first cleaned his automatic pistol and then fired it out of the door to see that it worked.

Notopoulos arrived only eight years after the end of a war in which the Cretans had maintained bitter and heroic resistance against the German occupiers. He found Sfakia in a ‘ferment’ of song. Everywhere the American ethnographer went, men were singing about the 1941 airborne invasion, the cruelty of the Germans, their burning of villages, their shooting of the innocent, the heroism of the Sfakiots themselves, the sons no less heroic than their fathers and grandfathers, and the bitter reprisals carried out by them against their own traitors and fifth columnists. The long island tradition of daring manliness, the kidnapping of brides, the maintenance of unforgivingly violent blood feuds and of loathing for the outsider – Roman, Arab, Venetian and Turk – was pouring out in this new generation of song. It is a suggestive connection: are the years after a war the great moment for epic? With the dreadful realities of the crisis over, can the miasma of epic descend?

The mountain bards in their black tasseled kerchiefs, knee-high boots and baggy trousers sang as Parry had led Notopoulos to expect, formulaically and repetitively, composing in performance, versions of songs sung in the morning different from how they were sung at night. Notopoulos recorded them all. One of his bards was a young man, Andreas Kafkalas, only thirty-nine, particularly gifted in what Notopoulos called ‘spontaneous improvisation’, the ability to sing a story for the first time without rehearsal.

After one of his epics about the German invasion and occupation, Notopoulos said he was surprised Kafkalas had not mentioned anything to do with General Kreipe, the commander of the German garrison on Crete. No, Kafkalas said, but in response to the American’s prompting, he thought he could sing a poem about him now. Notopoulos turned on the recording equipment and Kafkalas began. His tale was about as long as one of the shorter books of the Odyssey. His formulae filled whole passages of the song, all in the traditional fifteen-syllable Cretan line. How did he know, Notopoulos asked him later, to put fifteen syllables in a line? ‘I didn’t know the line had fifteen syllables,’ he said. ‘I don’t count the syllables, I feel them – it’s the melody that shapes the lines.’ The tradition was singing through him.

The kidnapping of General Kreipe was the most famous act of bravura special operations in the whole story of occupied Crete. Two British officers, Patrick Leigh Fermor and Billy Moss, had captured him, their whole enterprise conceived in Cairo but dependent on the networks of andartes, the Cretan resistance fighters. One evening in late April 1944, on the road between the general’s HQ at Archanes and his quarters outside Knossos in central Crete, the two Englishmen and a band of andartes stopped the German car, a new Opel, coshed the driver, dragged him on to the road (he was later killed) and bundled the general into the back of the Opel with a knife at his throat. The two British officers sat in the front, Moss impersonating the German driver, Leigh Fermor Kreipe himself, with the general’s hat on his head.

After a terrifyingly anxious drive through Herakleion, passing slowly through twenty-two German checkpoints, inching along streets filled with the men of the garrison who had just come out of the cinema, they drove out into the wild lands at the foot of Mount Ida, abandoned the car and headed off on foot into that harsh, dry and fissured mountain. For the next twenty days, as the Germans attempted to encircle them, looking for them with spotter planes but never detecting them, the general was led west halfway across mountain Crete, the party hiding in sheepfolds and caves in the daytime, stumbling on difficult mountain paths, often in the rain, at night, until they finally came down to a small bay west of Rodakino on the south coast. There they boarded a British motor launch which had been summoned by radio and, high on excitement and triumph, with their general safely aboard, made off for Alexandria.

I have walked the whole of their route, from where they dumped the car to the little bay where they embarked near Rodakino. It took me two weeks. I slept in chapels and vineyards, I burned in the sun in the daytime, froze at night at six thousand feet on top of a snowy Ida, and was often lost in the dry, echoing gorges coming down to the valleys. Griffon vultures swung across the sky. I ate cherries in the villages and for days at a time brushed through the dry, scented smoke of the Cretan garrigue. My boots after two weeks’ walking were shredded by the limestone shards of the mountains, my body crawling with lice from the places I slept, but my mind was filled with the mountain distances of that epic and beautiful island. A shepherd taught me a phrase – Yiassou pantermi Kriti!: Bless you, desolate Crete! – as the only words to be said when facing the long, dry emptiness of the mountains, stretching as a desert into the haze. It is a brutal world, and later that year the Germans executed ferocious, slaughtering attacks on the people of mountain Crete. In every one of the villages through which the Kreipe group passed, in between the cherry trees and the figs, the little tavernas and the shady plane trees, there is a tall marble memorial on which the names of their dead are listed.

The Leigh Fermor party never got as far west as Sfakia, but Kafkalas told his tale with only a little hesitation. He had heard it from another Cretan when in hospital in Athens. And now, he told Notopoulos, he was singing the song to him ‘to fulfil the obligations of Cretan hospitality’. But the song Kafkalas sang was an intriguing oddity. Almost nothing survived in it from the original story; truth had disappeared under a slew of the heroic. A single [untrue] English general [untrue] arrives in Crete and summons a hero from Sfakia, Lefteris Tambakis, to see him. [Untrue: Tambakis was a real figure, but he had never been anywhere near this operation.] The English general draws himself up to his full height, weeps over the cruelties being done by the Germans to the people of ‘desolate Crete’, and reads out the order to the Sfakiot hero that Kreipe is to be captured dead or alive [all untrue – no such order existed].

For the honour of Cretan arms, Tambakis knows what to do. In disguise he goes to Herakleion and finds a beautiful girl there [he didn’t]. She is the secretary to the German general [he didn’t have one]. He tells her that if she helps him, her name will be immortal in Cretan memory. She will join the catalogue of heroes. She agrees and ‘sacrifices her woman’s honour’ with the German general. Kreipe – called Kaiseri in this song – whispering across the pillow, tells her his plans. [Of course he didn’t.] She passes them on to Tambakis, and Tambakis goes to meet the English general at Knossos [there was no meeting there]. The ambush is laid. The andartes get ‘a long car’ with which to block the road [they didn’t], but Tambakis himself waits there on a beautiful horse [no horses were involved, but they always are in old Cretan songs]. The English general is by now pretty marginal to the story. The Cretans stop Kaiseri’s car, strip him naked [they didn’t], he begs for mercy for the sake of his children [he didn’t, but this is a motif that usually appears at these moments in Cretan poetry], and they start on the long trek over Mount Ida. Dogs [not used] and aeroplanes, called ‘birds of war’, hunt for the kidnappers, but to no avail. They arrive in Sfakia [they didn’t], where the people try to kill Kaiseri [they didn’t] before a submarine [it was a launch] sweeps him off to Egypt. Hitler is in despair [he probably was in June 1944, if for other reasons]. ‘Never before in the history of the world has such a deed been done.’

Nine years had passed between these events and this telling of them. Nothing in the Kreipiad is true beyond the kidnapping of a general and his leaving in a submarine. Whole characters and a different Sfakiot geography, plus the luscious fantasies of a Mata Hari seductress-spy, are laid over the top of any historical truth. If this is what could happen to a modern story in nine years, how could anyone hope that anything true might survive in the Iliad or the Odyssey?

At almost exactly the moment James Notopoulos was hearing the Kreipiad sung to him in Crete, and the idea was collapsing of an inheritance transmitted through song from the deepest past, precisely the opposite conclusion was being reached at the other end of Europe. In September 1953, a group of forty Celtologists gathered at a conference in Stornoway on the Outer Hebridean island of Lewis, flown in from all over Europe by the British Council. The key session in Stornoway was boringly advertised as ‘Paper on Folktales with Live Illustration’. No one guessed that they were about to hear something that would turn the Parryite orthodoxy on its head.

Also asked to the meeting, as its star turn, was a seventy-year-old stonemason from a village on South Uist, two ferries and a long drive away down the Hebridean chain.

Duncan Macdonald was a small man with an air of untroubled self-possession. He was not Duncan Macdonald but Donnchadh mac Dhòmhnaill ’ic Dhonnchaidh ’ic Iain ’ic Dhòmhnaill ’ic Tharmaid – Duncan the son of Donald the son of Duncan the son of Iain the son of Donald the son of Norman. They were descendants of the MacRury family of hereditary bards who had sung for the chiefs of the Macdonalds at the now ruined and abandoned castle at Duntulm, on the shores of the Minch, within touching distance of the northern tip of Skye. His father and brother were story-tellers, his mother a famous singer, her brother a much-loved piper and poet. He was one of the most gifted story-tellers in twentieth-century Europe, heir to the great traditions of Celtic story-telling which stretched far back into the Gaelic past.

Anything the singers Milman Parry had found in the Balkans could be matched by this inheritance, and Duncan did not disappoint. It was not the first time he had been the focus of attention for the folklorists, and on this afternoon in Stornoway he told a tale – it was ‘The Man of the Habit’, lasting about an hour – which he had told to transcribers four times before, in 1936, 1944, 1947 and 1950. This afternoon the delegates were given a booklet containing a transcription and an English translation of the way he had told it in 1950.

He began, as one of his hearers said, in Gaelic that was ‘polished, shapely and elegant … Everything he recited was given both weight and due consideration.’ But, as slowly emerged, this mild-mannered stonemason’s confidence in the tradition was matched by the extraordinary precision with which he told his tale. Scarcely a word was different from the printed version they held in their hands – a few tiny mistakes, substituting subhachas (‘gladness’) for dubhachas (‘sadness’), one or two interjections that were different and some synonyms changed, but on the whole the seven-thousand-odd words of the story were exactly as he had told them three years earlier. On analysis, all five of his versions were as good as identical. He had learned it like this from his father, and had told it like this ever since first learning it. The family had held it in mind as a kind of remembered heirloom, a hero tale, composed at least two hundred years earlier – there is an account of it from 1817 – which remained alive not just as a plot but in precisely the same words, transmitted unaltered from generation to generation.

In a world overtaken with the Parry hypothesis of composition-in-performance, this was revelatory. Duncan Macdonald had provided another way of seeing Homer, not as the poet who had written the Iliad and the Odyssey as his own works of art; nor as the poet who adapted and transmuted what he had learned to the situation he found himself in; but a poet who worked with a curatorial exactness, resisting the changes imposed by the passing of time, preserving antiquity in detail. For this kind of poet, stories were reliquaries in which precious wisdom and cherished understandings could be kept despite all the mutability of world and time. A poem enshrined memory. Its music denied death.

In Homeric Greek this understanding of the role of poetry focuses on a particular phrase: kleos aphthiton, in which a-phthitos means without death, undying, eternal, everlasting; and kleos, in the most revealing of all Homeric significance-clusters, means story, fame, honour and glory. In the Homeric mind, those four things are one. The tale told is itself a form of honour; honour exists in the telling of a tale; fame is to be found in the heroes of tales; their glory in life is the substance of honour; the tale of honour is the denial of death. Only if the tale resists the erosions of time can it make any claim to be the vehicle for glory. Undying fame is both the substance and the purpose of the Homeric poems.

In the years since then, ethnographers have discovered all over the world traditions of oral poetry which do not rely on the Parry method of composition-in-performance, which are not entirely formulaic, but which trust in the power of human memory to preserve with real precision the names, stories and words of the past. Duncan Macdonald’s son wrote down 150,000 words of stories he had heard from his father before he died. The great eighteenth-century illiterate poet Duncan Ban MacIntyre knew at least six thousand lines of his own poetry. According to the Scottish Homer scholar Douglas Young, there was an octogenarian crofter from the Hebridean island of Benbecula, a man called Angus McMillan, who

had in his head more than seventy tales lasting at least one hour each, and some novels lasting seven to nine hours, one of them running to 58,000 words, which is nearly as long as Homer’s Odyssey … [He] could talk for eight hours at a stretch, almost without a pause. On the nearby island of Barra, Roderick MacNed is reported to have told tales every winter night for fifteen years without ever repeating himself. On the Scottish mainland, in Lochaber, John Macdonald recorded over six hundred tales, each of them a comparatively short story complete in itself. An Irish taleteller recorded over half a million words of tales he knew.

The idea of human memory in monumental form allows one to push Homer beyond the ninth or tenth centuries BC. The epic poem, seen as the deepest of all recording mediums, releases Homer from time constraints, allowing his tales to plunge far back into the centuries before writing. It is a kind of time-release not unlike standing on a peak in Darien, seeing the Pacific widths of the past expanding before you. Parry was only partly right: it now seems clear that his model is one way, but not the only way, that Homer works. Homer unites and combines the formulaically made with the acutely remembered and the sparklingly invented. In the substance of its poetry, Homer is the inherited tradition in its multiple forms: both alive as the poem composed in performance and fixed, as monumental as the stone over a grave mound, the memorial of great things done long ago. Multiple in origin, multiple in manner and multiple in meaning, Homer in this light both knows the deep past and moves beyond it. He is both South Uist and Sfakia. And so the question emerges: what is it that Homer remembers?