IN THE STONE AGE, before man went in search of metal, you could have picked up nodules and nuggets of copper lying on the surface of the earth, or glimmering in the sandbanks of any stream. In some places, like the great copper body at Parys Mountain in Anglesey, copper was so thick in the ground-water that perfect branches, plant stems, leaves and nuts of the metal could be found in the dirt, where the mineral had somehow replaced the organic matter buried there.

All over Eurasia, that native copper was beaten into discs and rosettes, badges and brooches, and occasionally little needle-sharp awls and burins for working leather. In about 8000 BC in Anatolia, in Syria and northern Mesopotamia, people began to smelt it, the first smiths, magicians of heat and strangeness, drawing the metal out of the ores in which it is usually found. The heat of a pottery kiln is enough to release the metal from its oxides and sulphides, but even so the glowing emergence of a material which when cool stayed flame-bright can only have summoned a kind of awe. It may even be that the Arthurian story of the sword in the stone is a folk-memory of this emergent miracle: gleaming strength drawn from a rock.

From about 5000 BC, people all over Europe and Asia started hardening the copper, perhaps first by chance, by mixing arsenic with the metal when it was molten. But copper and these copper-arsenic alloys were rather soft, not the revolutionary material which after 3000 BC would transform Eurasia. Only then did someone, probably in Anatolia, discover that if you added tin to copper, you could produce a metal that would not only take a high shine – a brazen, visual hardness – but was physically hard, and could be sharpened to a fierce and lasting edge. This tin-copper alloy was bronze, and it would change the world. There is some tin in Anatolia, but in most places it is rare or absent, and across the bulk of the bronze-making world it had to be imported from elsewhere. Still nobody is certain where that tin for the Bronze revolution came from: perhaps from Bohemia in the Czech Republic, maybe from Cornwall, but more likely from Afghanistan. Whatever the origins of the tin, travel and connection became central to the culture of Europe. For the first time in the European Bronze Age (2500 to 800 BC), the exotic became desirable, and the distant prestigious. It became a world of interconnectedness, a culture founded on mobility, with ideas, beliefs and ways of life all travelling along the seaways and river routes of Europe and western Asia.

‘The broad picture,’ as the Bristol archaeologist Richard Harrison has written, ‘is of a continent with an imaginative map of itself that knew, through objects from faraway places, that other worlds existed and that they shared values as well as objects.’ A necklace of Baltic amber, found in a grave in Wiltshire in England, was made of beads shaped in Mycenae. The Nebra sky disc, found in central Germany, was made of Austrian copper, Cornish tin and Cornish gold. A Bronze Age wreck off the south coast of Devon carried a Sicilian sword. A piece of amber has been found at Bernstorf in Bavaria, inscribed with a word written in Linear B, the Greek spoken in Mycenae, along with gold diadems that resemble those from Mycenae itself. Afghan lapis lazuli appears in Greek graves. Folding chairs in Danish graves were made on patterns that recur in Greece and in Egypt.

Were these movements of things accompanied by people? Or was it only that objects were passed from hand to hand across Europe? Shipwrights in Bronze Age Scandinavia made craft that bear a striking resemblance to Greek prototypes. Carvings of otter-like animals on some Swedish tombs look very like the creatures engraved on Mycenaean signet rings. How did those ideas get there? Did Bronze Age Greeks actually make their way to Denmark?

The teeth of an early Bronze Age man who was buried not far from Stonehenge in southern England bear trace elements which show that he grew up somewhere in the Swiss Alps. Near him another man was buried, his relative, perhaps his son, with the same slightly faulty bone structure in his feet, whose teeth revealed that he had grown up in southern England. Cross-continental journeys were certainly possible in the Bronze Age, but was the whole of this proto-Europe alive with adventurers and travellers? Or people whose journeys were not of their own volition? Chemical analysis of the teeth enamel from twenty-four people roughly buried in a series of late Bronze Age pits at Cliffsend in Thanet in north-east Kent, from around 1000 BC, show an extraordinary set of international origins. Just over a third were from Kent (strontium and oxygen isotopes in drinking water carry unique chemical signatures), another third from southern Norway or Sweden, a fifth from the western Mediterranean, and the rest undetermined. Many of these people left their birthplaces when they were children between three and twelve years old. One old woman buried in Thanet was born in Scandinavia, moved to Scotland as a child, and at the end of a long life finished up in Kent. Almost certainly these people were slaves.

Certain clusters of human genes (the haplogroup E3bIa2) which have their heartland in the copper-mining districts of Albania, and are found in the people living there now, rarely appear elsewhere in Europe, except in two specific concentrations: one in the modern inhabitants of Galicia in north-west Spain, the other in the people of north-west Wales, both important centres of copper mining in the early Bronze Age. It seems inescapable that these genes are the living memories of Bronze Age people travelling the width of a continent to exploit the magical metal.

Bronze began to transform the Near East, and to have its effect in China, the Indus valley and the Aegean. Troy, on the far northern edge of that urban belt, became a trading city, controlling routes to the north. City-states emerged, along with writing, bureaucracies, specialist traders and central authoritarian government. Woven textiles were traded up into the Caucasus in return for copper from increasingly well-developed mines. In a belt that stretched east across the Asian continent, and of which Troy and the beautiful cities visited by Odysseus are the emblem and embodiment, urban civilisations emerged.

At the same moment, but further north, the new metal had an equally powerful effect on human history. A different, non-urban Bronze-based culture emerged. A cluster of economic, social, military and psychological changes came about in a wide swathe of country which stretched from the steppelands around the Caspian Sea through the Balkans and on into northern Europe. These changes created the civilisation of which Achilles is the symbol: not a city world but a warrior elite, ferociously male in its focus, with male gods and a cultivation of violence, with no great attention paid to dwellings or public buildings, but a fascination with weaponry, speed and violence. The heroes of this warrior world were not the bureaucrats of the cities further south, or the wall-builders, or the defenders of the gates, but men for whom their individuality was commemorated in large single burials, often under prominent mounds, on highly visible places among the grazing grounds cleared for their herds. Meat mattered in this warrior world, largely as a symbol of portable wealth when on the hoof and as the material for feasting when dead and cooked.

This semi-pastoral economic and political system was the breeding ground for a dynamic and mobile warrior culture which would eventually spread throughout Eurasia. There were many local variations and idiosyncrasies, and a complex chronology, full of time-lags, which mean that the same cultural phase occurs at different times in different places; but for all that, a single world of Bronze Age chieftainship stretched across the whole of northern Eurasia from the Atlantic to the Asian steppe. It is a world hinged to the idea of the hero, quite different from the developed, literate cultures of the eastern Mediterranean, and it is the world from which the Shaft-Grave Greeks emerged in about 1700 BC.

In his Greek heroes, Homer gives voice to that northern warrior world. Homer is the only place you can hear the Bronze Age warriors of the northern grasslands speak and dream and weep. The rest of Bronze Age Europe is silent. Echoes of what was said and sung in Ireland or in German forests can be recovered from tales and poems collected by modern ethnographers, but only in Homer is the connection direct. The relationship travels both ways. Homer can illuminate Bronze Age Europe, and Bronze Age Europe can throw its light on the Homeric world.

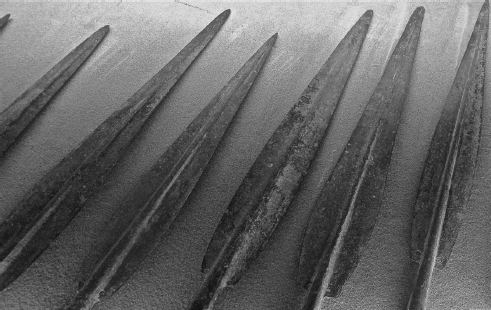

In places where you might least expect to find them, echoes of the world of Achilles come drifting up at you. And the weapons are at the heart of it. I have seen them now in museums in Wiltshire, in Naples and Syracuse, Bodrum, Athens and Nafplion, and in St Petersburg, Paris, Edinburgh, London and Boston, where collectors and excavators have gathered them. Anywhere you seek out Bronze Age weaponry, the same power gestures greet you from across the room: the seductive, limousine length of the blades, the oxidised green of the bronze, often now the colour of a mottled sea, the willow-leaf javelin points, the sheer length of the long swords with their golden hilts, the deep-socketed spear heads, the socket running as far back along the shaft as the spear head protrudes beyond it, the metal occasionally still wrapped in oiled cloth to preserve it.

If you look at one of these blades with Homer in mind, you see it for what it is: the tapering fineness of its double edges, coming to a point more gradually than anything in nature, those everlasting cutting edges going on and on like the leaf of a fine, imagined iris; or a slow-motion diagram of death being delivered; the strengthening midrib, narrowing along the blade but running to the very tip, so that it arrives there as delicate as a syringe; and the reinforcement at the root of the blade, a possible weak point where the shaft first narrows, vulnerable to the body of the victim twisting and kicking with the pain.

These blades are pure ergonomy, designed for a purpose, elegantly coalescing the necessary functions, the cut and the shove, two slicing edges and a penetrative rod for the best possible pushing of metal into flesh, and then the widening of the wound past the point, so that the man will bleed and die.

These are the wonder-weapons of the Iliad:

They clothed their bodies in gleaming bronze and Poseidon the Shaker of the Earth, led them, carrying in his strong hand his terrible long-edge sword, like lightning, which no one can stand up to in dreadful war. Terror holds men aloof from it.

These weapons are horrifying and beautiful, repulsive and attractive in the way the Iliad can be, for their lack of sentiment, the unadorned facts they represent, but also for the perfection with which they are made, their seamless match of purpose and material. The swords that have been found in Mycenaean graves are always exceptionally well-balanced things, the weight in the pommel counteracting the weight in the blade so that they feel functional in the hand, body-extensions, enlarging the human possibilities of dominance and destruction. The lances would have been useful in the hunt, to be thrown or to jab at cornered prey, but these swords mark a particular horizon in human history: they are the first objects to be designed with the sole purpose of killing another person. Their reach is too short for them to be any good with a wild animal thrashing in its death terror. A sword is only any use if someone else agrees to the violence it threatens; it will get to another man who is prepared to stand and fight. Some of the most beautiful decorated swords are found scarcely used, ceremonial objects to be carried in glory. But most of the rest show the marks of battle; the edges hacked and notched where another sword clashed on to them, worn where those edges were resharpened for the next time.

An air of threat and beauty hangs about them, even in their glass cases, labelled and sanitised, consigned to a curated past. They seem sometimes like caged predators, their violence lurking a quarter of an inch beneath the surface. Anyone who has ever walked out with a gun they liked, or even a rod well set up, will know something of this, its beautiful fittedness to your needs, ‘as snug as a gun’, as Seamus Heaney described the pen he chose instead of it, the sense a weapon has of extending your power over the material world, its promise, or at least taunting suggestion, of what it will be like when the fish takes the hook and the rod bends, and you feel in your hand that other creature’s struggle against your dominance; or when the bird you have been tracking crumples and folds with the shot, its head and wings useless, bowling towards earth, where the body lands football-like, a muffled heavy thump.

Our modern sensibility might wrinkle its nose against the pleasure the warrior world took in violence, but Homer cannot be understood unless that pleasure is also understood. Homer has a specific word for that death thump: doupeo, meaning ‘to sound like the heavy thud of a corpse as it falls’. It is always set against its opposite arabeo, to rattle and clash, the sound that armour makes when a man is felled. That pairing is a formula which fills a whole line, recording again and again the death of enemies:

doupēsen de pesōn, arabēse de teuche’ ep’ autōi

With a thud he fell, rattling his armour around him.

The thud and the rattle mark the falling apart of a man’s life, its coherence removed by death, the effect delivered by the gleaming bronze, the triumph of the new metal dominance, its penetrative masculinity and its cultivation of power. The sharpened blade transformed human relations.

Only once in my life have I had a knife held to my throat. It was thirty years ago. I was twenty-five years old and in Palmyra in the Syrian desert. In the early evening I was walking alone in the palm groves on the southern edge of the oasis, down the rutted tracks that curved through the trees beyond the ruins of the temple of Baal. The sun was coming through in rods, lighting up the bunches of fruit high in those trees, and between the shafts of light the air was soft and grey, almost milky. The warmth of the evening was feeling its way between my shirt and skin. A little boy passed me and said ‘Hallo’ in English, brightly and sweetly.

I was thinking how beautiful this place was after all the openness of the desert, coming as we had on a hard, rough track from Damascus, and was paying no attention to where I was wandering, kicking up the dust on the track with the toes of my boots. But the light was going, and after a while I thought I should return to where I was staying, the Hotel Zenobia, a mile or so the far side of the famous ruins, in the grid of streets of the modern town.

And so I turned back up the track, the way I had come. I could see the footprints my boots had made as I came down there. But I reached a crossing, where another track cut over, and could not immediately remember which to take. A young man, a little older than me, but shorter, with rather thick hair combed to one side, was leading his bicycle towards me. ‘Hotel Zenobia?’ I asked him. He looked up at me. ‘Hotel Zenobia?’ I asked again.

A look of understanding came into his face and he smiled, turned his bicycle around and led me along the track he had just come down. We had the usual, fruitless non-conversation between people who cannot speak each other’s language. After a few minutes we came to another crossing, and he seemed a little uncertain. I looked in his face to see if I could guess where he thought we should go, but as I did so he dropped his bicycle, grabbed me by my wrists and started to push me to the ground in front of him. It was always going to be hopeless, him being the shorter, and I held him and his arms away from me. He tried to trip me, as schoolboys do, by putting his foot behind mine, but to no end. It was faintly ludicrous, the two of us there in a kind of tussling non-embrace, on some track in the middle of an oasis in the Syrian desert. But there was anxiety in his eyes, now I looked into them.

I broke free of his hold, running back the way we had come, turned right at the first crossroads and ran on, hoping but not knowing that I was on the track to get out of the palm grove and into the openness around the ruins. I ran on, the path curving here and there between the different blocks of the plantation, until I came to a fork in the road. Which way? I had no idea, and stopped, trying to recognise the route home. But as I stopped he caught up with me. I looked down at him and saw that he had a large stone in his hand; he had been thinking of throwing it at me. But the instant I saw the stone he dropped it and took out a knife, the blade no more than four or five inches long, but coming to a point, the edges honed, scratched where he had sharpened them on a file.

He raised the knife to my throat and held the point just where you would put your fingers for a pulse, where the neck begins to curve round under the jaw. I could feel the metal point on my skin, but it did not cut me. Keeping it there, he led me back down the track we had both just run along. I didn’t feel any conscious fear. My breathing was slowing, my mind going cold, disconnected. He wanted to be somewhere we would not be disturbed. We turned off the track into a little patch of scrubby ground between the palm trees. There were some plastic canisters here, perhaps for oil. Neither of us spoke. He made me undress, holding the knife into the side of my neck as I did so. Surely I should have hit him then? Looking back on it now, I wonder why I didn’t. Why not just hit his face with my fist, knock him down and kick him once he was on the ground? Isn’t that what the warriors in Homer would have done? Break his skull, murder the man who threatened me with his knife? Wasn’t that the only dignified thing to have done?

But I didn’t. I behaved in the way that the ‘foolish children’ of the Iliad behave, submitting to the knife, too frightened at what that blade might do to my face and body to risk fighting him. Women and children in Homer are always called foolish because they do not risk death by confronting the enemy; they submit and suffer like sheep under a worrying dog. I knelt in the dust as he raped me, a pitiable little dog-like action from behind, the point of the knife jiggling in the side of my neck with his frantic movements, my mind observing this from afar and realising that the moment of greatest danger was not yet over: that after he had done with me, all the possibilities of loathing, resentment and shame, not to speak of the chance that I would report and identify him, might mean he would kill me.

I prepared for that moment as I felt him coming over my thighs and buttocks. It all seemed entirely prosaic, neither consciously frightening nor dramatic, not anything that would raise my pulse. This was my experience of the ordinariness of death, that everything that had made me what I was up to that moment – my father and my father’s father, my love of home, of the orchards and wheatfields that the Iliadic warriors always remember, and my wife in England – all of that was now perhaps to come to an end, without strangeness or mystery, but as one of the essential facts of being and non-being, of my life being bound up with the continued existence of the pulse in my body. I felt entirely animal, as if I and my body were co-terminous, everything about me dependent on the blade of that knife not cutting into me and draining my life into the Syrian dust.

In those few minutes, I moved through the full spectrum of Homeric reactions, from the child-like stupidity of acceptance of violence to the man-like recognition that I should risk killing him in order to be myself. This was when the fight for life would happen; this was my introduction to the world with which the Homeric heroes are so familiar; their life dependent on the death of those who are out to destroy them.

We stood up, I dressed, he did up his trousers, holding the knife in his hand, and I walked back alongside him, smiling, talking about Palmyra, just out of arm’s reach. We came to his bike and he picked it up, the knife still in the hand that held the handlebars. I made sure I walked with the bike between me and him. I kept talking to him, looking at him with my eyes smiling, acting ease and acceptance, waiting for the moment when he would stop again, and come for me, preparing for that, not in anything resembling rage or fear, but a stilled, intent cold-mindedness. As we walked along, I looked for the stones on the track which, when the time came, I would pick up and use to crush the skull-bones between his eyes.

It was getting dark. We passed the point where he had first caught up with me. The further we got, the safer I knew I was. We reached the edge of the palms and the blue of the open desert. He pointed me to the road I should have taken and then he turned away to the right, walking with his bike into the shadows of the trees. I went on across the desert towards the town and the hotel, where I stood for longer than I knew in the shower, recognising that I had understood something that evening: the banality of one’s own death, so much less terrible than the death of someone you love; its mysterious combination of everything and nothing; its lack of beauty or poignancy; the extreme calm that threat can summon; the clarity with which, when threatened with death, you must threaten death in return.

I knew nothing of Homer then, but I know now that these are all aspects of Homeric understanding. They emerge from a world in which use and imposition are part of the everyday fabric of life. The poems are not the overheated fantasies of palace-based thrill-seekers. There’s no ooh-ah here. Homer’s groundedness in the plain facts of killing is one of the guarantees of its truth.

A few years later I went in deeper pursuit of this northern, non-urban, metal warrior world, led first by the hint of a footnote in a book by Adolf Schulten, the German archaeologist who devoted his life to the recovery of antiquity in southern Spain. In 1922, in the first volume of Fontes Hispaniae Antiquae, he made the suggestion that he knew where Hades was, the underworld, which in the middle of the Odyssey Odysseus and his men visit in order to learn the way home from the old, blind seer Tiresias. It was, I recognise, a quixotic thing to do, to fly there, hire a car, drive through the concrete scurf of the modern Spanish coastline, to find the place where Odysseus, a fictional character in a phantasmagorical story from the Bronze Age, was said to have encountered some of the deepest truths Homer had to offer. It is the sort of behaviour you might find in a Tom Stoppard play or a High Victorian memoir, but as things turned out, in my few days of walking around the river valleys and dry cork oak pastures on the high borders of Andalusia and Extremadura – that most-marginal-imaginable of Odyssean landscapes – I felt as if I were cutting deep trenches into the Homeric world.

When I first read the Odyssey, no moment was more powerful for me than Odysseus’s visit to the underworld. Inner and outer landscapes were more intimately fused there than in anything I had ever read. The great man’s crew of time- and sea-worn sailors have been on Circe’s island, but are now cold and frightened, at the limits of the world. The coast of Hades is desolate, fringed with tall poplars and with willows whose seed falls from the trees before it is ripe. This place is everything the world of heroes is not: dark, colourless, silent and mournful.

Crowds of the dead surface to confront the crew. The ghosts, the psyches, shuffle towards them; their limbs are ‘strengthless’. All the varieties of death emerge: the old who had suffered much, the girls with tender hearts, the brides and unwed youths, and ‘great armies of battle dead, stabbed by bronze spears, men of war still wrapped in bloody armour’. They cannot speak. They do not have the life juices which would allow them to speak.

For the dead, there is no other choice than Hades. This is not punishment, but simply the place where in the end all people, however good and however holy, must go. Hell is the absence of life, the removal from the world of love and warmth which is the defining glory of life on earth. Hell is the house of loss. Only when Odysseus sprinkles in front of him all the good and fruitful things of the world – milk, honey, wine, water, white barley flour – and adds to them the hot blood of newly slaughtered lambs, and only when he allows the ghosts to sip at that life-blood, does the power of speech, the sense of human communicativeness, return to the spirits.

One by one they approach him, drink and speak: his friend Elpenor; Tiresias; and his mother. Odysseus longs to embrace them all, but as he moves to hold them, they rustle through his hands, slipping away like shadows, ‘dissolving like a dream’. They are nothing in his arms. Psyches are merely people from whom the life-defining qualities of people, their physical presence in the world, have been stripped away. Here are people in the grey, fleshless state to which death has reduced them. It is a vision of the beautiful, the regal and the desirable sunk to nothing but rustling, flittering spirit.

As Odysseus stands there, with the tears running down his cheeks, he sees the ghost of Achilles coming towards him, the greatest of all the warriors, the fastest and fiercest among them, worshipped almost as a god by the other Greeks at Troy, and now the greatest among the dead. His face is mournful, and Odysseus tries to console him. Achilles answers coldly and passionately: ‘Never try to sweeten death for me, glorious Odysseus.’ The word Achilles uses for ‘glorious’, phaidimos, is used throughout Homer to describe the heroes. But here in hell, it has a particular resonance. Its roots are in the word for ‘shining’ or ‘brilliance’. As the dead Achilles speaks, it is the world of lightlessness addressing the world of light and glimmer, the shining world from which Odysseus comes and from which Achilles is forever excluded.

This is one of the pivotal moments of the Homeric epics, the dead hero of the Iliad addressing the living hero of the Odyssey, the man of singular and unequalled heroism, who has already suffered his fate, speaking across the borders of hell with the living, slippery, ‘many-wayed’ man, polytropos Odysseus, whose life and destiny has still some glittering way to run. Death is addressing life and envying it.

Achilles makes the great central statement of the poems. ‘If I had a chance of living on earth again,’ the ghost says through his tears, ‘I would rather do that as a slave of another, some landless man with scarcely enough to live on, than lord it here over all the dead that have ever died.’ This is the Achilles whose pride had defined him in life, whose honour and sense of his own greatness had driven hundreds of men to their death, who had chosen death and a short life as the foundation of his glory. In the Iliad, Achilles had glowed with destructive beauty: he was a flaming star, a fire burning through a wood. His hands were ‘like consuming fire, his might like glittering iron’. His eyes burned like a furnace-core. His protective goddess, the grey-eyed Athene, had lit an unwearying fire that burned over his head. At every turn in his life he was quick and unforgiving. He was elemental in his strength, like a river unsusceptible to argument or compromise. But now, for this ghost, this burned-out, ashy wraith, any taste of life, of any kind, however humble, would be preferable to the half-lit half-existence of senseless wastedness to which he is condemned. The purity of death holds no attraction for the Homeric Greeks. Their world is one in which the felt, sensed and shared reality, the reality of the human heart, is the only one worth having.

As a measure of Homer’s skill as a dramatist and topographer of the emotions, he has Achilles address Odysseus again, the two of them still in tears, with the question that burns in the heart of any ghost in hell: ‘But tell me the story,’ Achilles says – the Greek word is mythos, meaning the ‘word’, the ‘rumour’, what men say, but also the plot, the pattern of the story – ‘of the lordly boy.’ He is referring to his son Neoptolemos, whose name means New War. Had he followed the Greeks to the wars? Had he fought as a son of Achilles might be expected to fight? Was he a boy a man might be proud of? Odysseus, drenched in love and pity for the dead hero, tells him all he knows of the beauty and courage of Neoptolemos: his calm when waiting with Odysseus in the belly of the Trojan Horse, his unwavering courage, and, perhaps more important, how the boy had ended the war unharmed and even unscarred, never stabbed by either spear or sword, but sailing home in his ship with his share of the spoils and ‘a noble prize’. He does not mention that in other stories of the Trojan War, Neoptolemos was the most savage of all killers at the fall of Troy, murdering Priam at the altar of Zeus and killing Astyanax, Hector’s child, by throwing him from the walls. In one version, Neoptolemos kills Priam by battering him with the dead body of his grandson.

Achilles does not hear this, but nevertheless can say nothing in response to what Odysseus does say. It is too much for any father, even the greatest of heroes. He can only walk away across this beautiful, monochrome hell, which is covered, like all stony wasteland in the Mediterranean, with stands of tall, pale asphodels. It is a moment to describe the desolation of death and the unbridgeable gap between the world of light and the world of dark. Achilles both possesses his son in his memory and knows he can never possess him again. Neoptolemos is not here, and Achilles can be nowhere else. Here, defined by death, is the central grief of experience. Odysseus tells his listeners what Achilles did next:

So I spoke, and off he went, the ghost of the great runner,

Loping with long strides across the field of asphodel,

Speechless in triumph at all that I had told him of his boy.

Adolf Schulten suggested that this scene occurred at the far western end of the Bronze Age world, in south-west Spain, because that is where the goddess Circe had told Odysseus to go:

Set up your mast, spread the white sail, and sit yourself down; and the breath of the North Wind will bear your ship onwards.

Bronze Age ships, on a broad reach, with the mainsail braced hard to port, could drive west with a north wind, the fastest of all points of sailing.

But when in your ship you have crossed the stream of Oceanus, where is a level shore and the groves of Persephone – tall poplars and willows that shed their fruit – there beach your ship by the deep swirling Ocean, but go yourself to the dank house of Hades.

These are plain instructions. Odysseus’s ship must sail beyond the gates of the Mediterranean, out through the Straits of Gibraltar, into the Atlantic Ocean, where the tides swirl and circle in a way unknown to Mediterranean sailors, and there find a beach with strange, cold, oceanic trees whose fertility deserts them under the salt winds. These are the trees of Persephone, the queen of death who is also queen of life, a vegetation goddess taken by Hades, king of the underworld, to be his consort, and in whose kingdom she presides over the sufferings of human souls. Odysseus would know he had arrived when he found her trees whose seeds would never be ripe.

But Circe is more explicit still:

There into the ocean flow Pyriphlegethon and Kokytus, which is a branch of the river of Styx; and there is a rock, and the meeting place of the two roaring rivers.

Homer’s geographic imagination understands scale and substance, and these are the giant rivers of hell: Pyriphlegethon means blazing or raging like a fire, used of cities when men torch them; Kokytus means howling or shrieking: it is the sound made by Priam and the women of Troy when they hear of the death of Hector; Styx means hateful and loathsome, the word used again and again for war, death and destiny. In rivers that make their way down to the great surrounding ocean, sorrow and fearsomeness slide out of the huge, dark, hidden continent called Hades.

Schulten thought he knew where this was. West of the Guadalquivir, and west of the straits of Gibraltar, two rivers flow out into the Atlantic at Huelva: the Rio Tinto, which means the red river, and the Rio Odiel. Where they meet in the estuary at Huelva, a great hoard of Bronze Age weaponry, now in Madrid, was dredged up in 1923. The confluence of those rivers is below a conspicuous rock where the monastery of Santa Maria de la Rábida has stood since the Middle Ages, and where in 1492 Christopher Columbus made his final prayers before sailing west for Cathay.

It may not be much, but there were undoubtedly Mycenaean connections in southern Spain; Mycenaean ceramics have been found at Montoro on the Guadalquivir, east of Cordoba. If there were connections to the Cornish tin supply, then the sea routes came past here. It is possible that the estuary at Huelva is Homer’s gates of hell.

I was there alone one autumn, the south wind blowing warm and delicious out of Africa. There are beaches where, as it says in the Odyssey, ‘they stowed their gear and laid the mast in the hollow hulls’, waiting to see what would come to them at the ends of the earth. There is a flat shore, as Circe promised; a rock, or at least a large mound; two rivers, but neither is roaring nor made of fire. The estuary waters are brown and polluted. Slimed stumps of old quays stand up to their shins in the water. Waders teeter on the water’s edge. The trees are no longer the seed-spreading willows but clumps of eucalyptus and palms in rows. Phoenician, Egyptian, Greek and Cornish objects have all been dredged from these shallow waters, but if this is the gate of Hades, the shores of a lightless eternity, you would hardly guess it.

But go inland and the landscape starts to change. Both the Rio Tinto and the Rio Odiel push on to the north of Huelva. These river valleys were one of the most important sources of metals in the Bronze Age, because the hills on either side are filled with veins and big ore-bodies of copper, tin, gold and silver. Both rivers in their upper reaches are deeply changed by the metal country they run through. The Odyssey, with its man-eating monsters and vicious whirlpools, is a gothic poem, full of the nightmarish and the terrifying, the imagined sufferings of its heroes, but these garishly-coloured mineral valleys share that atmosphere: the toxic, the metallic, the otherworldly, the lifeless and the threatening all fused into some kind of recipe for hell.

Stop the car, walk down to one of these riverbeds and you will find the world drenched in strangeness. It is a gaudy and bloody trench, earth transmuting into another planet. The rocks and water are both iron red. Sandbanks in the river look as if they are the hulks of abandoned iron beaches. These are not the neat pleasure-landscapes of an island kingdom, but big, harsh, continental, inherently violent. Flakes of white quartzite shine through the water between ribs of rock that veer from red to tangerine to ochre and rust to flame-coloured, flesh-coloured, sick and livid. In between those red rocks are green snakeskin copper-rich boulders, glinting grey-eyed green minerals from within the orange depths.

The rivers themselves are deeply and naturally poisoned. This is the earth polluting itself. Where it has dried it has left white chemical residues, scurfy scabmarks of receding poison tides. Only one kind of strange, green, longhaired weed can live in it. Apart from that the water is cloudless, mineral red but entirely clear. This is a place in which almost nothing can live, in which fruit would drop before it was ripe. Those swirling fronds of green hair, seven, eight, nine feet long, are swept downstream around the flakes of rock. Underwater, the whole bed of the stream is coated in a thick dust of iron poison, iron solids precipitated from the water, a fungal metal scum. Where, in a back-eddy, the current slows, a crusted porridge of the bloody slurry gathers in the pools, and no fish rise.

An occasional dragonfly hangs its diamond-blue wings over this hell-water, but never with a mate. No songbirds. High above, some distant hawks. Perfectly white flies lie dead, caught in the mineral slicks. If Homer, in Chios, heard of this, of course he would have put Hades and Persephone here. I have never seen a place more suited to them.

At the mining town of Rio Tinto itself, there is a museum where the mysteries of this metal world are on display. If you want to rediscover the Bronze Age entrancement with minerals in the raw, this is the place. In neat, old-fashioned glass cabinets you will find some of the strangest things the natural world can offer: fractured blue-silver flakes of galena; silver-gold cubes of iron pyrites; bulbs of calcite, erupting and diseased like glaucous eyeballs. Cinnabar is a stone blood-pudding, its red shot through with purples and blacks, the background for lilac amethysts. Green malachite is here, with azurite its close cousin, a Prussian blue only to be found in Alpine gentians. Sometimes the pyrites coats the skin of a rock in what they call calco pitita, as if a breath of gold had been blown over the stone. But nothing is more like the jewels of a hell palace, or poetry from the depths, than the rainbow stripes of Goethite, the crust of an indigo, lilac and green-gold planet.

The extraction of mineral ores here can only have been hell. The metals were mined from the overlying rock in difficult, cramped, dangerous and unforgiving conditions. Much of the ore was loosened by setting fires in the underground chambers, the heat splitting the rock, which could then be pulled away by hand or levered off with antler picks. Otherwise, it was simply beaten with hard stone hammers that were waisted to take a rope binding, which have been found in the ancient mines, their ends battered with the work they had done before they were cast aside. Human limb bones are occasionally found beside them deep in the ancient workings.

Twenty miles from Rio Tinto, in the dry hills near the village of El Pozuelo, at a place called Chinflón, a Bronze Age copper mine remains much as it was left when the seams were abandoned about three thousand years ago. It is not easy to find, about an hour’s walk from the nearest road through poor, scratchy cork oak and eucalyptus hills. This is high and silent country, nearly sterile with its metals, scarcely visited now, a universe away from the industrialised agriculture of the coast. There are deer slots in the dust of the track and the views are enormous, twenty miles in all directions over the burnt forested ridges, taking in at their limit the vast bloody gash of the modern quarries at Rio Tinto. There are pale-winged buzzards in the sky, dust seems to be everywhere and salt sweat runs into your eyes and on to your lips.

The top of the hill at Chinflón is still smothered in the grey-greenish toxic spoil from that ancient mine. Red and orange rock flakes prod up through it. Coppery grey-green lichen spreads over the stones. Because of the way the rock strata are aligned, the flakes run along the crest of the hill in a series of narrow parallel ridges, so the summit is spiked skywards, like the vertical plates on the back of a Stegosaurus. Between those flakes is where the metal-bearing veins of malachite and azurite came to the surface, and where the Bronze Age men dug away for it, mining into a series of slits, pursuing the vein as it sank away from the air and the light, scrabbling with their heavy hammers, diving after the metal like dogs down burrows.

There is a modern chainlink fence surrounding the workings, to prevent you getting at them, but you can fumble and scrape your way under it easily enough. Within the rough enclosure are the deep but narrow rock trenches cut into the earth, twenty or thirty feet long, six feet wide at their widest; others just wide enough for a ladder to lead down into their dark. They push seventy or eighty feet below the surface. Coppery, blue-leaved plants grow on the mine lip, as if the metal had entered their veins. Clots of quartzite sit there like fat in pâté. Steps are cut into the walls of these red, dark mineral hollows, the rim of each step slightly higher than its cupped floor so that the hold feels safe enough as you go down. But you descend gingerly. In one of them, nineteenth-century iron chain-ladders are set into the little cut cliff-faces, where later miners hoped to find what their predecessors had abandoned. The air feels cool as you drop into the shadow, lowering yourself into the rock-bath, the sweat cooling on your back, the mine wrapping its walls around you. At the bottom, in the half-dark the slits are wet and mossy, comforting, mysteriously juicy, liquid, the walls of Hades seeping with grief. Any noise you make is echoey. But the sides of the walls are vulnerable. There is not much a pick would be needed to dig out. Touch them and rock pebbles clatter down below you into the dark, ricocheting off the lower walls. I collected flakes of greenish, snakeskin rock, the minerals in them glimmering as they turned through the light from above.

All mines are full of spirits. In the lead mines in County Durham, the men always spoke of the rock as an animal, ready to push at you as you made your way along an adit or down a shaft. In Cornwall the tin miners called the mine spirits the Knockers, as they knocked back at any man cutting away at the metal-bearing veins. They were the mine itself speaking. In sixteenth-century Germany, according to the great Renaissance theorist Georgius Agricola, these spirits were ‘called the little miners, because of their dwarfish stature, which is about two feet. They are venerable looking and clothed like miners with a leather apron about their loins.’

Most of the time the Knockers were gentle and friendly, hanging about in the shafts and tunnels, only turning vicious if the miners ridiculed or cursed them. You needed to treat them with respect. Whistling could offend them, as could intentionally spying on what they were doing. They liked to be left in the shadows or the depths of the mines, or even behind the rock, knocking from inside it. Many miners placed small offerings of food or candle grease in the mine to feed and satisfy them. If you were good to them, they would show you where to find the metal.

As Ronald Finucane, the historian of the medieval subconscious, has said, ghosts ‘represent man’s inner universe just as his art and poetry do’. Ghosts are what you fear or hope for. The mine, if the gods favoured you, could provide a sort of magically immediate richness not to be found in the surface world. But all was hidden until you found it. And that reward-from-nothing was reflected in the miners’ attitudes to metals. In Cornwall, they thought that iron pyrites when applied to a wound would cure it. Even water that had run over iron pyrites was said to be medicinal. Cuts washed in it would heal without any other intervention. But also in Cornwall, and in the parts of the USA where Cornish tinners emigrated and took their ancient beliefs with them, Knockers were thought to be ugly and vindictive. Miners who were lamed were known to be victims of the Knockers’ rage. Insult them and they could damage you for life.

It is a commanding cluster of images: lightlessness, the spirits of the underworld, the hope for treasure and happiness, wounding, cures, the half-glimpsed, the dreaded, a realm of pain and power. This is the dark basement of the Achilles world, the place that metal came from, emerging through processes that were unknown and unintelligible to most of the population, but somehow providing the power-soaked tools with which the killer-chiefs dominated the landscape.

It is at least a possibility that Homer’s Hades is a nightmare fantasy fuelled by the Bronze Age experience of the mine: a place in which spirits are clearly present but not to be grasped; where life has sunk away from the sunlight to the mute and the insubstantial; to beings that are only half there, regretting the absence of the vivid sunlight above; where a mysterious sense of power lurks in the dark. ‘When it comes to excavated ground, dreams have no limit,’ Gaston Bachelard wrote in The Poetics of Space. When you are underground, ‘darkness prevails both day and night, and even when we are carrying a lighted candle, we see shadows standing on the dark walls … The cellar is buried madness.’

There is a sense of transgression at Chinflón, a feeling that this place was once alive and that the miners hacked at its life, as if they were hunting it, digging out its goodness, a form of rough and intemperate grasping, the masculine dragging of value from a subterranean womb. No one could be in the high, lonely mine at Chinflón, with its rock walls pressing in around them, and an almost oppressive silence filling the gaps between the stones, and not sense the reality of Hades as the house of sorrows, a toxic pit where the price of glory is buried suffering.

To the north, beyond the Sierra de Aracena, a ridge of dry, flaky schists on the frontier of Andalusia and Extremadura, another dimension of the Homeric world makes itself known. Distributed across a wide province stretching over southern Portugal and south-western Spain are some of the most vivid memorials of the warrior world Homer’s poems describe. They are stone stelae or slabs, cut in the Late Bronze Age, from about 1250 to 750 BC, designed to show the nature of a hero’s life. Other stone stelae, many shaped to look like people, can be found all over the Bronze Age world, but these are among the most articulate. None of them remains where it was found, and Richard Harrison, the Bristol archaeologist, has written a catalogue of the hundred or so that survive, listing their modern locations: one is in a bar in the Plaza de España in the village of San Martín de Trevejo on the Portuguese border north of Badajoz; others are in Madrid, Porto, in many local museums, in a school, in a town hall, in people’s gardens and houses, one used as a seat at the entrance to an estate, another as a lintel over a window. A couple were reused as gravestones in Roman antiquity, with the name of the buried men cut across the Bronze Age designs. Many are beautifully exhibited in the museum in Badajoz. No doubt there are more still lurking unseen in walls or foundations.

The beautiful, hard landscape of Extremadura is natural horse and cattle country. Long, brown distances extend in all directions. Stone corrals are topped and mended with thorns – as they are in the Odyssey – and little mustard-yellow damselflies dance through the grasses. The pale roads wind over the hills, tracing the contours between the olives and the cork oaks, with the tung tung tunk tunk of the sheep bells a constant metal music beside them. Oaks that have been stripped of their cork are now date-black, as crusty as the blood on a cut. Grasshoppers flash their amber-ochre underwings. Cattle gather in the shade. Lizards seem to be the only liquid. It is above all a stony place: whitewashed upright flakes of schist marking the boundary between estates; bushily pruned olives peering out above stone walls; stones gathered in the dry scratched fields into big cairns, little round fortresses of solid cobble.

None of this is different from the state it was in three or four thousand years ago. Stock were raised then on the wooded savannahs, as they are now. Cattle-herding was the basis for all wealth. A low understorey of grass sustained the herds under the evergreen oaks. Nothing would have been more nutritious for the autumn-fattening pigs than the fall of acorns. Wheat, barley and beans were grown then in small patches of dry farming as they are now.

In this big, open, manly environment, the stelae were often placed at significant points, where drove roads met or forked on a hillside, where they crested a pass or came down to a river crossing. Some commanded wide panoramas. They were meant to be seen. You were meant to encounter them as you crossed the country. They were created for public display. Some were attached to graves, but not a majority. These were miniature, highly individual monuments intended to mark the presence – and dominance – of great men in their place.

The stelae are, in another medium, the Iliad of Iberia: heroic, human, repetitive but individualised. They mark the shift away from the communal values of the Stone Age, when joint graves gathered the ancestors in a community of the dead, to a time which valued more than anything else the display of the glorious man. None is more than six or seven feet high – these aren’t great communal menhirs; they are on the scale of gravestones – but they are not recumbent. There is no knightly sinking into death here. Each is a standing monument to the vigour of a person. Gods do not appear: men dominate. The man himself is often shown as a kind of stick-figure, pecked into the surface of the slab, probably with a bronze chisel, and around him are his accoutrements, the things that made him the warrior hero he knew himself to be. And the catalogue of those heroic objects is a pointer to the values of the warrior world he wanted to record. To see these images is the strangest of sensations: it is, suddenly, Homer, 1,800 miles from Ithaca, more than two thousand from Troy, drawn in pictures on Spanish stone.

First there are the astonishing shields, dominating one stele after another. In the very early examples, the shield even takes the place of the man himself, and stands there for him and his world. The shields are huge, as big as a man, round but notched at the top, made of many concentric rings, the symbol of resistance and resilience, usually shown with the handle visible in the centre. In other words, they are seen from within the world that is protected by them. These are our shields, including us. They are the shelter for the life this man dominates, and in their massive, cosmic, many-ringed roundness they symbolise the universe of wholeness which the warrior protects. They are, in other words, the simple graphical equivalent of the great shield of Achilles which Hephaestus the smith god creates for the grieving warrior chief in Book 18 of the Iliad.

Only because Homer survives can you understand entirely what the Iberian symbols hint at. Like the many-ringed shields of Extremadura, Achilles’s shield has a threefold rim, and there are five layers to the shield, all constructed within its governing circularity: the earth and heaven, sea, sun and moon at the full, all the famous stars, marriages and feasts, dancing men, with flutes and lyres playing, an argument over the blood-price payable for the victim of a murder, with wives and little children standing on the walls of a besieged city. Fate herself appears here in a robe that is ‘red with the blood of men’, but this is neither a sentimental nor a tragic vision of the world: everything is here, ploughlands and cornlands, harvest and sacrifice, ‘fruit in wicker baskets’ and a dancing floor, like the one at Knossos in Crete, with young men and women together. In bronze, tin, silver and gold Hephaestus made a depiction of the whole world of sorrow and happiness, of justice and injustice, fertility and pain, war and peace. Many shields in Homer are described as ‘the perfect circle’ – a visual signal which confronts the sharp, narrow insertion of the blade. Even the Greek word for a shield, aspis, means the smooth thing, the thing from which roughness has been smoothed away. Achilles’s shield is only the most perfect. In Homer as in Extremadura, the shield is the encompassing symbol of the warrior king.

Then come the weapons: sword, spear, dagger, bow and arrow, very occasionally a quiver, and almost invariably a chariot, with the horses attached, their bodies shown in profile, the chariot in plan, drawn like this in Portugal and Spain, but also, extraordinarily, appearing in the same way on the Bronze Age rock carvings of southern Sweden.

The weapons are the necessary instruments of the martial life, the tools for establishing central aspects of the hero complex: maleness, heroic individuality and dominance. It is what comes next that re-orientates any flat-footed view of Bronze Age warrior heroism. These killer chieftains were obsessed with male beauty. The great Greek heroes all have blond hair (unlike the Trojans, who are dark-haired), and they have lots of it, lustrous, thick hair being an essential quality of the hero. Achilles had hair long enough for Athene to grab him by it when she wanted him to stop attacking Agamemnon. Hector’s hair, after his death, lay spread around him in the dust. Paris, the most beautiful of all warriors in the Iliad – too beautiful – so rich and thick was his hair that he looked like a horse, ‘who held his head high and his mane streamed round his shoulders’. The male gods are just as thickly maned. And the beauty of the warrior chiefs is inseparable from their power as men.

All of this appears on the stelae of the Iberian chiefs. Beyond their weaponry, carefully picked out on their memorial slabs, appears all the necessary grooming and beauty equipment: mirrors, combs, razors, tweezers, brooches, earrings, finger rings and bracelets. These accessories of male beauty are not consigned to some private preparatory ritual. Making the Bronze Age warrior beautiful is central to the idea he had of himself. Here is the handsome gang-leader, made more handsome by what he wears and how his body is prepared for its appearance among men. None of this culture would be possible without the bronze blades, but those blades are not its destination; they are the means to reach what these other precious objects describe: the mirror for a powerfully present idea of the self; the comb for grooming the beautiful hair; tweezers more likely to pluck an eyebrow than to take a splinter from flesh; brooches, earrings, rings and bracelets to adorn the beautiful man. When the river gods of the Trojan plain wish to attack and destroy Achilles as he is on his rampage, clogging their streams with the slaughtered dead, one says to the other in encouragement:

His strength can do nothing for him, nor his beauty, nor his wonderful armour.

Beauty is one of the elements that make him the most terrifying of men. The mirror, the comb and the tweezers are also instruments of Bronze Age war.

There is another detail that recurs on many stones, almost the only exception to the otherwise crude depiction of the heroes’ bodies. Time and again, the fingers of the warrior-hero’s hands are shown outstretched, explicit and over-life-sized. His hands seem to matter more than any other part of his body, perhaps because they were the part of him with which he imposed his power on the world around him. The hand is the agent of the burning warrior self, the essential instrument of the weapon-wielding man. That is also the role played by hands in the Homeric epics. Both Hector and Achilles have ‘manslaughtering hands’, and it is Odysseus’s hands that are steeped in blood as he exacts his final revenge on the suitors. It is as if the hands had concentrated in them all the destructive power of the warrior hero. And when, in the Iliad’s culminating scene of mutual accommodation, Priam the king of Troy comes to Achilles in the Greek camp, it is through the hands that the drama is played out:

Great Priam entered in and, coming close, clasped Achilles’s knees in his hands and kissed his hands, the terrible man-slaughtering hands that had slaughtered his many sons.

Homer rings those repetitions like clanging bells at moments of intensity and high purpose. And here, the word continues to boom on through the meeting. Achilles hears Priam’s plea for the body of his precious son Hector to be returned to him for burial. That pleading love of the father makes him think of his own distant father in Phthia. Priam’s words

roused in Achilles a desire to weep for his father; and he took the old man by the hand, and pushed him gently away. So the two of them thought of their dead and wept.

And again, when they had finished weeping, Achilles ‘took Priam by the hand’ and spoke to him words of pity and shared understanding of the pain men suffer in a careless world. The outstretched fingers of the Iberian warriors also carry all that love and violence within them.

There is one further object which binds together Homer and the Extremaduran stelae. On one stone after another, alongside the killing equipment and the beauty equipment, is something at the heart of the Bronze Age warrior world: the lyre. Sometimes they are drawn many-stringed; on a few they are as large as the giant universe-shields; on many, the lyre is shown as no more than a simple frame with two or three strings across it. But all of them signify the same thing: here is the instrument with which this warrior can sing heroic songs of deathless glory. The weapon, the beauty equipment and the lyre are all integral to his world. He exists in memory; in some ways he exists for memory. Just as Odysseus sings the tale of his own adventures when he finds himself at dinner with the king of the Phaeacians, Achilles is a man who sings heroic songs of deathless glory. That is how the other heroes find him when in Book 9 of the Iliad they come to his shelter, hoping to persuade him to rejoin the battle:

And they came to the huts and the ships of the Myrmidons [Achilles’s men] and they found Achilles delighting his mind with a clear-toned lyre, fair and elaborate, and on it was a bridge of silver; this he had taken from the spoil when he destroyed the city of Eëtion. With it he was delighting his heart, and he sang of the glorious deeds of warriors; and Patroclus alone sat opposite him in silence, waiting until Aeacus’s grandson should cease from singing.

It is a moment, like Glaucus’s account of the leaf-generations of men, when the passage of Homeric time stops for a moment and when, in its privacy and lovingness, the world of brutality withdraws with the help of a lyre. That is what the presence of the lyres on the Spanish stelae says: Homer is not only about the heroic world; Homer is the heroic world. It is the realm of gang violence, in which pity and poetry have a central place.

If there were any doubt that song was a central part of the warrior complex, a discovery in one of the remotest parts of north-west Europe in the summer of 2012 changed all that. Archaeologists working in the High Pasture Cave on Skye found the burnt and broken remains of the bridge from a late Bronze Age lyre. Homer – or at least the forms of warrior song on which the deepest elements of Homer draw – was a universal presence across the whole of Bronze Age Europe.

The Iberian stones might be seen as a kind of heraldry, the symbol-cluster for an armed knight. But they are also the first European biographies: he drove a chariot, strung a bow and killed with it, wielded spear and sword, held the shield, was beautiful and generous, lived here, sang his song. It seems from the distribution of the stelae that each warrior territory was no more than about twenty-five miles across. Seen as a kingdom, that is exceptionally small. But seen as an assertion over the landscape by a single powerful individual controlling about 270,000 acres, it is impressive. These are not petty empires but great estates. They are gang territories, equivalent to the ‘kingdoms’ described in the Homeric catalogue of ships. Nowhere are there any great buildings or constructions. All focus is on the power-body of the chieftain. His men cluster around him. His individual destiny is bound up with theirs and with the fate of the kingdom. It seems unlikely that many of these ‘kingdoms’ outlasted the life of the man who made them. It is a place of endless, repetitive violence and competition, in which ‘who your father was’ is important, but not enough. Honour must be revalidated in each generation. An unused sword rusts in the scabbard, and each life follows the one before, as Glaucus said, as the leaves of each spring follow the fallen leaves of the previous autumn.

Some of the stelae show that story. One of the richest is now in the Museo Arqueológico Provincial in Cordoba. It was found in April 1968 by some farm workers at the foot of an ancient wall, a good block nearly six feet high and about thirty inches wide. They hauled it on to their tractor, carelessly smashing the sides and scratching the face of the stele, and took it to the nearby estate of Gamarrillas, thinking it might be good for building stone. But they noticed the engravings on one of its faces. By chance some archaeologists working nearby saw it for what it was and saved it.

A huge warrior figure dominates the scene, with outstretched hands and his penis hanging beneath him. He has a bracelet on one arm, and his whole torso is decorated with what might be a patterned cloth, his armour or maybe a whole-body tattoo. Even like this, scratched into limestone, he radiates significance. Of his chieftainliness there is no doubt. There is a little brooch next to his head, and his fighting equipment is gathered in the spaces around him: a spear, a shield, and a sword in his right hand, still in its scabbard. Beneath him is a comb, a shield and what may be a woven carpet. This is how he was in the glory of his life. But this stone also records his death. He is accompanied by his hunting dogs, both visibly male, and by his chariot. Around them groups of mourners hold hands, maybe dancing. There are no faces. All is in the body. This is a life that has been lived and is now over. But for all that, an atmosphere of Homeric transience is soaked deeply into these little figures. Like the epic poems, this stone is a regretful glance back to a wonderful past, which, like the man, has gone.

Most of the stelae were thrown down, taken away and dumped after they were set up. Others were deliberately effaced. But that should come as no surprise in a world of constantly shifting chiefdoms, a power-churn where no glory lasted more than a generation or two. The same circumstances that gave rise to the stelae, to the warrior-complex of which they are such vivid testimony, would also guarantee their destruction. Like the weaponry, the killing, the grooming, the insistent body-focus and the presence of the lyres, this delight in the destruction of the enemy is everywhere in Homer too, above all in the exulting over the corpse of a defeated enemy.

When one hero kills another in Homer, there is no grief or sympathy across the divide. It is a moment of triumph, when maleness achieves its undiluted self-expression. In Book 11 of the Iliad, as one example, Odysseus is on his destruction-drive and fixes his spear into the back of a Trojan called Sokos, thrusting it straight in between the shoulderblades, so that the point comes out of Sokos’s chest. The Trojan then thumps to the ground – doupeo – and Odysseus stands over the dead body:

Ah Sokos, son of battle-minded Hippasos, breaker of horses, death has been too quick for you and ran you down; you couldn’t avoid it, could you, poor wretch? Your father and oh-so elegant mother will not close your eyes in death now, but the birds that eat raw flesh will tear you in strips, beating their wings thick and fast about you; but to me, if I die, the brilliant Achaeans will bury me in honour.

There is no pity in this. The destruction Odysseus celebrates is wonderful to him. Nothing is more beautiful than the sight of Sokos’s dead eyes staring at the sky. Odysseus is happy at the dreadfulness he has done to that man and his now-grieving family. He has destroyed the power of that dynasty and enhanced his own. There is no sense of tragedy. He has merely defaced their memory. Their stone is down and gone; his remains upright, triumphant, crowing.

Richard Harrison has emphasised the loneliness which this ideology imposed on the warrior hero. ‘He is a unique and isolated figure,’ Harrison has written,

whose arm is strong and deadly; he is devoted to combat, which he actively seeks out; he is detached from ordinary social space and so is shown to be tremendously swift, able to cross time or distance between worlds; and he is a very dangerous person in society and is therefore much better detached from it and sent away on a quest where he cannot harm ordinary mortals.

That loneliness clearly attached to Hector; to Agamemnon in his pomposity, his distance from love; to Odysseus on his journeying; even to Paris, the loathed creator of the war. Heroism disconnects. And the loneliness applies to no one more than to Achilles, as profoundly isolated as any figure in world literature. In his great and terrible confrontation with Hector in Book 22 of the Iliad, after Hector has killed Achilles’s great friend Patroclus, Achilles makes the ultimate statement of heroic loneliness, the isolation of the warrior which is also the dominant image on the Iberian stelae: a big man surrounded by his things, very occasionally by some mourners or even co-warriors, but essentially alone, trapped in the glory of his violence. ‘Hector, you, the unforgivable, talk not to me of agreements,’ he says, using the word agoreue for ‘talk’, the word used in the agora, the meeting place where citizens come to mutual accommodation. Achilles does not belong there; he belongs in the wild:

There are no oaths sworn between lions and men, nor do wolves and lambs come to some arrangement in their hearts. They are filled with endless, repetitive hate for each other. Just so, it is impossible for you and me to be friends, nor will there be any oaths between us till one or other is dead, and has glutted Ares, the god of war, who carries his tough leather shield, with his blood.

In Celtic Ireland, on the far western edge of this hero world, where round, ridged leather shields have been dug from Bronze Age bogs, stories from the heroic age have been recorded in which

the heroes gave orders that they should be buried standing upright, fully armed on a prominent hill, where they could face their enemy, awaiting the moment of resurrection when they would fight again and by this means continue to protect their people.

Those same upright warriors, continuing to haunt the living world, as enraged and violent as they were in life, also appear in the Icelandic sagas. Perhaps these are stories of the ultimate, cosmic loneliness, a measure of the inadequacy of the heroic idea, which only that weaponless, hand-connecting moment between Priam and Achilles could hope to assuage.