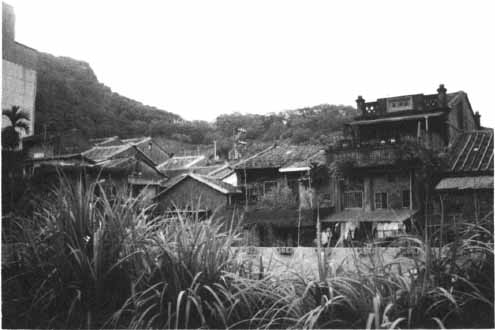

Rooftops in the town of Sanhsia.

The Transformation of Local Elites in Mid-Ch’ing Taiwan, 1780–1862

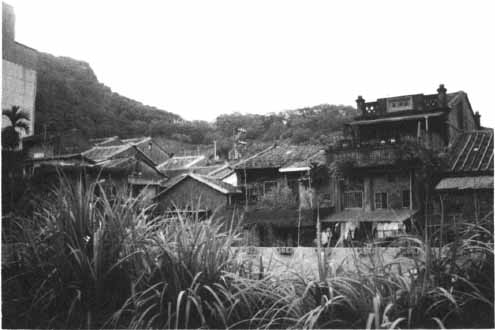

Rooftops in the town of Sanhsia.

The early development of Taiwan during the Ch’ing dynasty took place approximately from 1680 to 1770 and is generally referred to as the “pioneering stage” in the island’s history. During that period, the Ch’ing government headquartered its administrative organs in the prefecture city (fu-ch’eng) of Tainan and gradually established a bureaucratic system of both civilian and military control. The Ch’ing also adopted policies for organizing and colonizing the P’ing-p’u aborigine tribes in the western region of the island. At the same time, the Ch’ing gradually converted to private property the royal lands and agricultural properties that had been established under the control of Cheng Ch’eng-kung (Koxinga) after his conquest of the island from 1662 to 1683. Under the new system, landowners had full property rights over their land with effective control over management and production decisions and with full tax obligations. As a result, many wealthy merchants from the coastal areas of the mainland in Fukien and Kuangtung provinces rushed to the island to explore and develop the vast open grasslands on the island to seek new opportunities for becoming wealthy. Some applied to local officials to acquire the requisite documents granting them the right to develop and acquire ownership over large tracts of land. Others leased land from the aborigines, which granted them cultivation rights, or they simply laid claim to underdeveloped, barren land. After securing their new properties, many of these homesteading property owners returned to their home villages and towns on the mainland to hire neighbors, relatives, and friends to return with them to Taiwan and assist in the opening up and development of their land.

According to local regulations on Taiwan, homesteaders were required to supervise their tenant farmers and to pay tax to the government based on the amount of land opened up and put under cultivation. Tenant farmers were also required to develop a certain amount of the land within a specified period of time and were under obligation to pay rent to the owner on a seasonal basis. Homesteaders were granted permanent ownership rights over the land while tenants were given permanent cultivation rights, that is, permanent leasing rights.

In addition, the Ch’ing government determined that aboriginal landlords enjoyed the same rights as their Han counterparts. Han settlers were also prohibited from intruding on the lands and territories of the island’s non-Han population. To get around this restriction, however, many Han immigrants negotiated tenancy agreements with the aborigine landowners that produced a system of aboriginal-Han landlord-tenant relations. Basically, as private ownership was legally established for these lands, landlords—both Han and aborigine—were encouraged to monitor the agricultural production and rent payments of their tenants, a system that, to a considerable extent, helped to strengthen the social order in rural Taiwan.

Until the 1720s, as a result of increased great demand on the mainland for the rice and caned sugar produced on Taiwan, many wealthy merchants and landlords formed partnerships as a way to pool capital for construction of large-scale irrigation and water control systems. This, in effect, brought about an agricultural revolution on the island that, by the mid-eighteenth century, led to the opening up of vast tracts of irrigated land for rice and sugarcane production by tenant farmers. This system led to a situation in which, before 1800, Taiwan supplied the mainland with 500,000 tan [1 tan = 50 kilograms] of rice annually, thereby dramatically increasing rice supplies in China’s southeast coastal regions, which reduced inflationary pressure on food staples on the mainland. In addition, Taiwan also exported approximately 600,000 tan of sugarcane to northern China, Japan, and Southeast Asia, earning large sums of Mexican silver dollars. These huge sales of caned sugar and rice meant that, by the mid-eighteenth century, Taiwan had developed from a remote frontier island into a vibrant new grain market in Southeast Asia.1

Many historians have characterized the period from the 1780s to the 1860s as the “intermediate stage” in the development of Taiwan that occurred before the opening of its ports to foreign trade.2 Overall during this period, Taiwan was distinguished by several characteristics, beginning with the formation of its landlord class. Even though the homesteaders and aboriginal proprietors retained cultivation rights, these groups did not themselves directly engage in agricultural production. Instead, the general practice was to lease these rights to tenant farmers and others in return for rents in kind. In subsequent years, many of the tenant farmers who had secured permanent rights subleased surplus lands to other tenants, from which they, in turn, collected rent in kind, usually in the form of grain. These tenant farmers were referred to as “estate masters,” or “farm managers” who enjoyed management rights over agricultural lands, which they often subleased to secondary tenants. Under such an arrangement, land rights were divided between two parties: the proprietor who retained ownership rights over the land and the “farm manager” who exercised management rights, which entitled him to collect rents in cash or kind and to buy and sell these rights. And, of course, the farm manager had to pay rent to the landowners. In general, proprietors were referred to as the “primary lease holder” and the farm manager as the “secondary lease holder.” Under this system of “dual ownership of land,” proprietors and farm managers dominated Taiwan’s agricultural production and distribution. In addition, since most proprietors did not reside on their lands, they became absentee landlords who did not directly supervise their tenant farmers. In contrast, most farm managers lived on the land for extended periods and thereby became intimately familiar with the agricultural economy of their lands, including the production decisions of the tenant farmers. In addition, they also participated in local activities involving religious temples and village security measures. This was why the influence of the farm manager in the rural areas was much greater than that of the proprietors. After the end of the eighteenth century, therefore, most people referred to the farm managers, rather than the proprietors, as the “landlord class.”

A second major characteristic of the island during the “intermediate stage” was the surge of immigration from the mainland. According to census data, immigrants into Taiwan numbered 600,147 in 1756, 839,800 in 1777,912,000 in 1782, and 1,786,883 in 1824.3 During these earliest stages of settlement, newcomers constituted fully half the total population, and from 1782 to 1811 they made up two-thirds of the island’s population. Most immigrants to Taiwan left the mainland because of increasing population pressure and the growing shortage of land, which had severely taxed people’s capacity to make a living. This was particularly the case following the uprising on Taiwan led by Lin Shuang-wen in 1786, which led the Ch’ing government to lift its restrictions on immigration to the island by individuals whose relatives had already emigrated there.4 The impact of these immigrants on the island was quite profound. On the one hand, most were young single males whose devotion to hard labor contributed substantially to the development of the agricultural base on the island. It was their diligent work that led to the extension of wet-rice paddy agriculture to relatively remote areas of Taiwan and substantially enhanced the sustainable development of island agriculture. On the other hand, since the opening up of new lands on the island could not keep up with the increasing numbers of immigrants, more and more people went landless and without work and as a result became part of a growing army of wanderers. Some in this group joined secret societies, which often became embroiled in riots and uprisings that increasingly threatened the stability of rural areas on the island.

Scholars who have examined official documents and materials have come up with a rough calculation of the number of uprisings and civil disturbances in Taiwan during this period. From 1684 to 1895, 159 major incidents of civil disturbances rocked Taiwan, including 74 armed clashes and 65 uprisings led by wanderers.5 During the 120 years from 1768 to 1887, approximately 57 armed clashes occurred, 47 of which broke out from 1768 to 1860. In other words, most disturbances and uprisings occurred during the mid-Ch’ing era, when Taiwan was undergoing very rapid social and economic transformation.6 The reasons for these various outbreaks were quite complex. One was the pervasive corruption of local Ch’ing bureaucrats and the general backwardness of Ch’ing soldiers stationed on the island, which often led to incidents that engendered popular outrage. Another reason was that most of the immigrants to the island came from different regions on the mainland and were unable to agree on a workable distribution of water rights and other resources, over which they frequently fought. Before 1780, most of these conflicts broke out in areas inhabited by immigrants from Fukien and Kuangtung. After 1800, such conflicts were concentrated in territories inhabited by immigrants from the Chang-chou and Ch’uan-chou regions in Fukien province and in areas where immigrants from Fukien and Kuangtung resided in close proximity. Usually, the secret societies set up by wanderers often benefited from these clashes as they were able to expand their network of social influence through all sorts of means. Until around 1840, most of the clashes and uprisings occurred primarily among residents from Chang-chou and Ch’uan-chou, led by individuals from wealthy landlord families who had resided on the island for two to three generations. Not only did these individuals own huge tracts of land, but they also were backed by local powerful religious organizations and could mobilize large numbers of tenant farmers as militia. Generally speaking, the major goal of such clashes was to gain control over land resources and water rights. But by far the most important reason was to use these forces to maintain and enlarge the power of the landlords at the local level in a situation in which Ch’ing officials could not effectively protect the property rights of landlords.7

In light of these facts, the purpose of this chapter is to discuss the transformation of the rural landlord families and the local elites during the period when Taiwan society was converted from a frontier region to a settled society. First, the formation of the landlord class will be discussed and, then, the social and political background of the emergent local elites. Here it is argued that the Ch’ing civil and military bureaucratic system on the island failed to adjust to the increased demands on administrative management created by the rapid transformation and development of Taiwanese rural society. This failure, in effect, fostered an increasing reliance on social connections among people from the same clan, while armed clashes broke out as these same groups’ sought to defend themselves and also tried to expand their areas of influence and control. Until 1860, most landlord families settled down in the countryside where they devoted considerable energy to building up local armed militia and to setting up clan organizations in the traditional fashion. By 1860, most landlords had assumed the characteristics associated with a local strongman in response to the general failure of the Ch’ing bureaucracy to provide for local security and protection. Several prominent landlord families even managed to rely on their extensive local connections to be appointed to semiofficial posts in exchange for assisting the Ch’ing in suppressing local uprisings.

The origins of the landlord class in Taiwan during the Ch’ing dynasty are very complex. In the early stages of class formation, landlords were composed of three groups: civil and military officials; homesteaders from the mainland; and the aboriginal tribes. Subsequently, in order to prevent civil and military officials from gaining a monopoly over the land, the Ch’ing dynasty decreed that all land be under private ownership. Hence, from the mid-eighteenth century onward, a system of private ownership emerged in which homesteaders from the mainland and aborigines comprised the majority of the landlord class. However, since, as was pointed out above, there was great reliance on tenants to farm the land, this rather simple ownership system was quickly transformed. During the initial period of settlement, homesteaders and aboriginal landowners did not engage directly in actual farm work but, instead, leased out the land and then collected rents, part of which they paid out as tax. The tenant farmers, in contrast, devoted themselves wholeheartedly to pooling the capital and applying the labor necessary to convert large swaths of barren territory into arable land. In return, they were ultimately granted permanent tenancy rights, which meant that proprietors could not increase rents or terminate their leases. In areas where tenants lived and worked the land, they often subleased surplus lands to other farmers and collected their own rents. In addition, tenant farmers also had the right to sell their leasing rights or even to pawn the land. These rights meant that permanent tenant farmers, in effect, enjoyed landlord status while the proprietors were prevented from interfering in their management decisions. This turned the ownership rights of the proprietors into a “lease deed” in which their rights were restricted to collecting rent on an annual basis. The farm managers, in effect, exercised full management rights including the sale or transfer of land on their own. In general, the practice on Taiwan was to consider rents paid to the landlord as the “primary rent” (ta-tzu), which amounted to about 10 to 15 percent of the farmer’s annual harvest. Rent paid to the farm manager was known as the “secondary rent” (hsiao-tzu) and constituted about 50 percent of the cultivator’s output.

Before the late eighteenth century, the asking price for land underwent constant increases as the number of immigrants to the island generally outstripped the available land. This effectively created a system of “dual or multiple ownership of land.” Not only were ownership rights over a single piece of property divided between the proprietor and the farm manager, but in some cases the farm manager also pawned his rights.8 This was because many investors believed that the profits earned by the farm manager were greater than that of the proprietor, and for that reason they invested considerable capital to buy the cultivation rights from the farm manager or the proprietor.

Some of these investors directly engaged in agricultural production, but most simply took the cultivation rights as a kind of commercial investment that yielded yearly rents. Their estimate of the value of cultivation rights derived not from the actual size of the plots but, rather, from the amount of annual rent guaranteed by the lease. In this sense, land rights no longer referred so much to actual ownership of property as to what became known as a “commercial lease.” Moreover, since the secondary lease offered a much greater return than the primary lease, and, considering that the farm manager often resided on the land where he could directly monitor the work of the tenants, the farm manager (the secondary leasing agent) had more effective control of the farmland in terms of production and distribution than did the proprietor (the primary leasing agent). As a result, the former was able to gain greater social and economic benefits.

From the 1780s onward, many resident secondary leasing agents replaced the absentee primary leasing agents as the managerial class and major source of rural capital and loans, effectively making them the dominant social class in the countryside. Whenever primary leasing agents were in need of cash they would pawn their ownership rights to rich peasants (that is, the farm managers). Thus, the relationship between the proprietor and their tenant farm managers emerged into one of leaser and banker. As a result, the ownership rights of proprietors, particularly among the aborigines, gradually slipped into the hands of the farm managers.

Following the uprising on Taiwan led by Lin Shuang-wen in the fifty-third year of the Ch’ien-lung era, the Ch’ing government sent a scholar official by the name of A-kui to the island to investigate the social and economic conditions that had fostered the uprising. Properties owned by people who had joined the uprising were confiscated by the government. In his report prepared for the emperor, A-kui described the situation on the island in which primary leasing agents were the de jure landlords and secondary leasing agents the de facto landlords. He also noted that the annual rents collected by proprietors ranged from six to eight tan for every chia [approximately eleven mu] of rice paddy while the secondary leasing agents collected up to 10 tan per chia in rent. Thus, the total value of primary and secondary leasing agents and the respective social and economic status of the two groups were, in effect, contrary to expectations. This phenomenon, it should be pointed out, became even more prevalent in the early nineteenth century. In the thirteenth year of the Tao-kuang emperor (1833), a Ch’ing official named Ch’en Sheng-shao provided the following explanation as to why the leasing rights of the primary leasing agent had become relatively less valuable in comparison to those of the secondary leasing agent.

Farm managers collect the largest rents because they control the flesh and bone of the land while the homesteaders collect relatively small rents because they merely control the skin of the land. Why is it that rents paid to the primary leasing agent are relatively small and those paid to the secondary leasing agent are relatively large? With a rent of around 8 tan on an [average] piece of land and 4 tan on the dwelling, very little profit is earned by the primary leasing agent. This small return reflects several conditions: the lack of a formal or written agreement between the parties; the view on the part of tenants that the secondary leasing agent is the real landlord; and the fact that the proprietor cannot arbitrarily change tenants. As for the secondary leasing agent, he collects upwards of 20 to 30 tan on the land. No agreement is signed with tenants who simply receive a receipt based on rent paid in kind in an amount determined by the farm manager. While farm managers often resist paying the primary leasing agent, this does not occur with the secondary leasing agent. This is why the value of the latter’s stake is considered greater.

These observations by Ch’en Sheng-shao reflect the fact that farm managers had two weapons at their disposal: First, they held one-year leases with their tenants, and once the lease had expired, they were completely free to take on new tenants; second, farm managers were also in a position to directly monitor the work of their tenants and to collect up to 50 percent of their harvest as rent. This in effect meant that the farm manager could direct the work of their tenants and also usually collect more sizable rents. By comparison, the proprietor was only able to collect the fixed rate of 8 tan while they were also obligated to pay a relatively fixed amount of taxes on their property, which significantly reduced their return on the land, especially in comparison to the return enjoyed by farm managers. In addition, most proprietors chose to live in towns and urban areas, where they could enjoy a better life-style but where they also were more subject to meeting their tax obligations. This effectively isolated them from rural life and agricultural work, which caused most landowners to be generally ignorant of both the location and size of their holdings. This led to increasing reliance by proprietors on agents who were sent into the countryside to collect rent where they often encountered resistance from both the farm manager and the tenant farmers. Once conflict broke out, the primary leasing agent and the farm manager became mortal enemies locked in constant conflict. In a recent study by Wang Shi-ch’ing and Stevan Harrell of local elites in the Shu-lin area of the Taipei basin, the authors noted that farm managers effectively replaced the proprietors as the dominant class in the countryside. During the period when the Shu-lin area was attacked by the Japanese in 1895, these authors also noted that proprietors generally sided with Lin Pen-yuan and the Japanese in repelling attacks by the locals, who had organized a so-called righteous army composed of farm managers and tenant farmers who led the opposition against the Japanese.9 Overall, this historical evidence indicates that the secondary leasing agents enjoyed a rather intimate relationship with their tenant farmers and that they, rather than the primary leasing agents or proprietors, constituted the real local elite.

During the early era of Ch’ing rule in Taiwan, the basic policy of the government was to maintain the stability of the existing social order. In general, this entire policy relied heavily on military rule. Security for the island was the responsibility of a brigade-general who headed a number of different military units, including coastal security units and naval forces stationed in Fukien. In the 1730s, 12,670 regular soldiers (and at times upward to 14,000) were sent to the island for duty from their regular base in Fukien. These troops were rotated every three years and were stationed in several areas, including the seat of Ch’ing administration in Tainan prefecture city and other local government sites, plus at river mouths and critical seaports. Overall, the number of soldiers stationed in these areas was greater than generally found in comparable areas on the mainland. Since the population and income on Taiwan were insufficient to support this large force, the Ch’ing government was forced to transfer resources from Fukien and Chekiang in order to make up the difference. And given that Taiwan was a primary supplier of rice to mainland markets and an important strategic island, the Ch’ing was willing to maintain a significant military presence despite its high costs.10 From this distribution of troops, it is evident that their primary purpose was to protect the offices of the various prefecture and county governments and to prevent illegal immigration into the island. Most troops stationed at river mouths amounted, however, to only a few squads and were thus generally unable to provide adequate security for the life and property of the many tenant farmers.

As for the civil administration, the highest-ranking official was the inspector, who exercised jurisdiction over both Taiwan and Amoy prefectures. In 1727, the official title of this position was changed (a common practice during the Ch’ing) along with its jurisdiction, which from that point onward covered Taiwan and the P’eng-hu archipelago. Because of the relatively remote location of Taiwan and the complex and diverse origins of its population, along with the constant threat of local uprisings, the Ch’ing government exercised great caution in selecting its highest-ranking official posted on the island, who was an intendant of a circuit. In principle, qualifications for this post included substantial administrative experience and exemplary moral conduct. The intendant of a circuit was under the direct jurisdiction of both the Fukien governor and the governor-general of Fukien and Che-kiang. During the initial period of Ch’ing rule, the intendant was in charge of the administrative work on the island including local tax collection, though he lacked the authority to report to the emperor directly. After the suppression of the Lin Shuang-wen uprising in 1788, however, the Ch’ing government felt it necessary to learn more about conditions on Taiwan and so allowed officials at the rank of intendant and brigade-general to report directly to the emperor so as to avoid any delay in deploying local military forces in the event of another uprising. At the same time, the Ch’ing government also altered the structure of the civil and military administration. On the one hand, it granted more power to the intendant, giving him the authority to supervise and monitor military and political affairs; on the other, the emperor also gave the brigade-general more authority over judicial and administrative matters. In addition, in order to effectively monitor Taiwan’s affairs, the Ch’ing government also ordered the commanding general and governor-general of Fukien and Chekiang to make annual inspection tours of Taiwan to ensure the most effective allocation and deployment of military forces.11

Under the jurisdiction of the intendant, there were two important administrative positions: the civil prefect and the coastal defense subprefect. The civil prefect was in charge of collecting land and property taxes and adjudicating criminal cases among residents. The coastal defense subprefect was primarily responsible for the supervision of ports and docks and coastal shipping and also for preventing mainland residents from slipping into the island as illegal immigrants. The civil prefect, in turn, was in charge of three counties, T’ai-wan, Feng-shan, and Chu-lo, which included offices set up to assist the county in gathering social and economic information and to assist in apprehending thieves. Since the term of office for Ch’ing officials was limited to three years, they were forbidden to bring along their wives or other family members. The most important matters, therefore, ended up being taken care of by local officials. Unfortunately, the level of education and training among these local officials was often lacking, leading them to misuse their power and exploit both the immigrant settlers from the mainland and the aborigines. The result was widespread antigovernment riots and uprisings such as in 1723, when Chu Yi-kuei reacted to unbearable exploitation by local officials by leading an uprising. After this incident, the Ch’ing government responded by punishing corrupt officials while it also realized that some local government offices had become so bureaucratic that they were unable to manage the vast rural areas in the central and northern part of the island effectively. It was for this reason that an administrative change was effected in which Chu-lo county was broken up into Chang-hua county and Tan-shui sub-prefecture, which assumed jurisdiction over the entire region north of Ta-chia-hsi. In 1776, despite the fact that the majority of the P’ing-p’u aborigines had become very “Hanified,” they still became deeply involved in disputes with the Han over land rights and other such conflicts. To deal with this situation two subprefecture offices were established in Tainan and Lu-kang with the authority to oversee public security work, to manage the buying and selling of land, and to deal with the various problems created by the loss of aboriginal land rights to the Han.12 The establishment of these subprefectures meant, in effect, that the P’ing-p’u aborigines had been effectively integrated into the social and political system of the Han and had been brought under the umbrella of the rural security system. In 1787 following the Lin Shuang-wen incident, the Ch’ing government changed the name of Chu-lo county to Chia-yi county. And in 1812, following the takeover of northeast Taiwan by armed Han people and after a number of villages had been built, the Ch’ing government set up the Hamalan subprefecture to manage agricultural affairs for both the P’ing-p’u aborigines and the Han. From then until the 1870s, after the Taipei basin became the center of tea, camphor, and sugarcane production for international trade, the Ch’ing government set up Taipei prefecture along with three additional counties, Hsin-chu, Tan-shui, and Ii-lan. These various administrative changes reflected a major shift in the political and economic center of power on the island from Tainan to Taipei.

This expansion of the civil and military offices indicated that the Ch’ing government had generally resisted any local administrative reorganization until after population growth had become so great that it brought about serious social conflicts. The same pattern was also evident on the mainland where the Ch’ing resorted to administrative reorganizations as a way to restrict the growth of the bureaucratic system.13 However, since Taiwan was a more mobile and unsettled society and generally lacked the system of village elders and clan organization prevalent on the mainland, whenever conflicts arose on Taiwan, it was up to the local landlords, farm managers, and aboriginal leaders to solve these problems and resolve local disputes. This, in fact, is the reason that the local elite emphasized building up their own private militia. Further, since many of the bureaucratic officials and soldiers sent over from the mainland often abused their power by collecting illegal taxes and skimming off profits, the local population had no alternative but to gather in secret and form organizations along ethnic or geographic lines to protect their property rights and living standards from bureaucratic parasiticism. These self-defense groups and organizations followed the practices of more traditional clan organizations by becoming involved in social conflicts that often posed a major threat to the rural social order.

In 1721, a Taiwan resident of Fukienese ancestry named Chu Yi-kuei mobilized the people of southern Taiwan and started a major uprising in which local officials were killed and many villages plundered. In the beginning of the uprising, Chu basically succeeded in uniting the population of Fukienese and Kuangtungnese to oppose the Ch’ing. Later, however, internecine disputes split Chu’s forces into two groups that did their own killing and looting. Such divisions among Fukienese and Kuangtungnese in this uprising effectively sowed the seeds of disputes between these two groups that would fester for many years to come.14

In 1782, Chia-yi and Chang-hua prefectures experienced large-scale social disorders between people of Chang-chou and Ch’uan-chou backgrounds. The roots of this disorder lay in a dispute over gambling debts that had broken out between two villages composed of people from Chang-chou and Ch’uan-chou. The conflict spread when both villages sought allies from their kin in nearby areas. Local headmen in some areas used the conflict as an opportunity to expand their economic interests and to carry out acts of revenge over old vendettas. The conflict was further intensified by the mobilization of unemployed wanderers from nearby areas. Local officials meanwhile were basically helpless in their attempts to mediate the conflict, which eventually expanded to a few dozen villages. During the period of the greatest strife, several thousand villagers from numerous clans were brought into the fray by local leaders who organized their followers into militia units along the lines of common language or surname. More than four hundred villages were burned to the ground and several thousand people killed while many residents of nearby areas were forced to flee.15 Some turned to their clan groups and leaders for help, while other tenant farmers picked up and moved to areas composed of people from the same ancestral background where they hoped to create some sort of collective defensive network.

In 1786, a member of the Lin family of Wu-feng named Lin Shuang-wen set up an organization called the Heaven and Earth Society (T’ien-ti hui) under the slogan of killing officials and fanning disorder. This turned into an uprising that eventually involved several tens of thousands of participants and lasted for over a year, making it the largest such conflict in the history of the island. Following suppression of the uprising, local officials collected information indicating that as many as 70 percent of the participants were unemployed wanderers. Further examination, however, revealed that many of the “rioters” actually owned considerable amounts of land, “as much as 3,500 chia, or more than 33,000 mu.”16 Such evidence indicated that, although a substantial portion of the “rioters” were unemployed wanderers, landowners and farm managers were also involved, usually as leaders. Furthermore, it was generally believed by the Ch’ing government that the uprising had resulted from the commingling of residents from Chang-chou and Ch’uan-chou in Fukien with people from Kuangtung between whom there were constant conflicts over land and water rights. In response, the Ch’ing ordered the local commander, Fu K’ang-an, to resettle people out of the island’s central regions so that locals from these separate areas would now live apart and conflicts could be reduced.17 This decision led to substantial changes in the village system at the hands of officials. At the same time, several local strongmen were afforded the opportunity to rebuild villages destroyed in the conflict, while residents from the same ancestral homelands or of the same surname were able to create their own local militia forces. After the outbreak of the uprising led by Tai Ch’ao-ch’un from 1862 to 1865 (discussed below), the government finally realized that most local leaders in this and other such conflicts were local strongmen who had organized secret societies and other such organizations. Tai Ch’ao-ch’un and Lin Jih-ch’eng, leaders of the uprising, were, in fact, from wealthy landlord families dating back several generations who had also served as leaders of local militia. Yet another participant was a man named Ch’en Nung, who was also from a family of considerable wealth and who had provided food and other such supplies to the thousands of participants in the uprising.

Leaders of various organizations involved in the conflict were also from influential landlord families. Before the outbreak of the conflict they had organized various secret societies devoted to venerating the local goddess Ma-tsu, which they used as an opportunity to expand their power for eventual conflicts with others over land and water rights. Once an uprising was threatened, this led to the assimilation and militarization of local organizations as various villages joined together, usually in groups composed of people with the same surname or language group. This was done to protect themselves from outside attack or to launch their own attacks against any and all opponents. Local strongmen with considerable landholdings also formed their own more powerful groups composed of relatives, friends, and tenants.

Although local officials of the Ch’ing could not halt the formation of these local organizations and groups and were helpless in stopping the outbreak of conflicts over land and water rights, they did adopt policies aimed at ensuring a kind of balance of power among these local forces and at eradicating the social conditions that fostered major uprisings. For instance, after the 1830s, some local officials, such as Yao Ying, demanded that local commercial organizations and rich farmers donate money to assist the many homeless wanderers with food and shelter and to provide them with some work to reduce their inclination to become involved in uprisings. In 1831, an official in Tan-shui by the name of Lo Yun realized that the local military forces at his disposal were woefully inadequate and so decreed the “Four Rules of Decorum” and the “Eight Forbiddens,” which effectively committed local leaders and clan heads to maintaining local social order. He also decreed as a guiding principle of punishment for any offender that “involvement by any family member means punishment for all.” From 1847 to 1854, Hsu Tsung-kan was the intendant of the circuit in Taiwan who attempted to persuade the local governor to set up organizations to apprehend thieves and to provide for local self-defense. According to a study of local security organizations in northern Taiwan during the nineteenth century by Mark Allee, local officials were often so short of staff that they were unable to manage the affairs of the villages and instead recruited local leaders to serve as managers or trustees to help mediate local problems. Many of these local leaders were not, in fact, local strongmen but, rather, elderly people or prestigious local leaders. In ordinary times, they assembled residents at local temples to announce government decrees or to assist in mediating local conflicts. This made it possible for government orders to be promulgated despite the shortage of local officials. In this way, various local groups were recruited to become part of the bureaucracy.18 As it was the powerful landlord families whom local officials tried to entice into service, we must therefore analyze the process by which this class of local elites was formed.

During the early period of the Ch’ing dynasty, the majority of immigrants to Taiwan settled in rural communities among people of the same ancestral or geographical background. As time passed, many of the landowning farmers organized themselves into clan groups to protect their property rights and to pool their capital. These groups were generally set up in the name of a common ancestor and were known as clan “cooperatives.” Members of these organizations who were generally from the same ancestral area, signed an agreement delineating their various rights and obligations governing entry and withdrawal from the cooperative.19 On the one hand, such organizations united villagers in collective self-defense in the unstable environment of rural Taiwan. On the other, these groups pooled clan capital and labor for investment in large-scale irrigation and water control systems that benefited agricultural development and production. In the early nineteenth century, when the landlord class had become firmly established and had already accumulated substantial amounts of property, they began to set up consanguineous organizations, based on common geographical background, as well as intervillage ancestral and spiritual worship groups. Many landlord families, after having engaged in agriculture for two or three generations, also set up family clan organs commonly known as “share groups.” The primary function of these groups was to honor the “pioneering generation” of ancestors who had come to Taiwan in the early years. Before the family patriarch divided up clan property, a parcel of land was set aside to support ancestral worship. Rent collected from these lands was to be used primarily by later generations to carry on ancestor worship, and thus the property could not be sold. Chuang Ying-chang and Ch’en Lien-rung have studied the history and development of the various clans in the Miao-li area of northern Taiwan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They found that, after 1790, residents there established clan organizations based on consanguineous ties. In the 1850s, many landlord families also adopted the practice of maintaining clan lineage records.20 Properties devoted to ancestor worship and to the various clan organizations both symbolized the localization (pen-t’u-hua) of landlord families. They were also important landmarks in the social transformation of Taiwan from an unstable, immigrant society to a more stable, settled one.21

Moreover, as a response to the threat of conflicts between people of different ancestral backgrounds, new villages and residential areas were built, consisting of people from the same clan or language group, or of the same religion. They too engaged in common defense and protection against outside enemies, at times including the Ch’ing government. For instance, in 1832, Chang Ping, a resident originally from Chang-chou, Fukien province, led a resistance to Ch’ing officials by farmers and residents around the town of Chia-yi who opposed the shipment of rice out of the area. This incident stemmed from a particularly devastating drought that had afflicted the rural areas of central and southern Taiwan, which by substantially cutting into the rice harvest convinced villagers that they had to hold on to their product. Yet, once corrupt local officials were bribed by shady merchants and traders to ship out rice surreptitiously, a full-scale rice riot quickly ensued. In the beginning, Chang Ping only wanted to lead the villagers to resist corrupt local officials. Later, however, with growing tensions between the Fukienese and Kuangtungnese, the conflict expanded from an anti-Ch’ing action into a general anti-Kuangtungese movement. In the end, as more and more migrants and drifters joined the fray, the movement turned into an old-fashioned fight between Fukienese and Kuangtungese that engulfed the entire island. But once the conflict died down, significant changes were effected in residential areas and general living patterns that gradually brought about greater commingling and mutual assimilation among more and more people. On the one hand, powerful families emerged as local armed strongmen; on the other, temples and places of worship that were formerly restricted to people of the same ancestral and geographical background were expanded incorporating entire villages and instilling a set of common beliefs and identities among immigrants from different backgrounds. For example, the Three Mountain King Sect (Sanshan Kuowang) had been traditionally confined to Kuangtung immigrants. But with the growing assimilation among the local population, people of both Fukienese and Kuangtungnese ancestry joined in revering this spirit despite their previous conflicts and tensions.22 Common places of religious worship, in effect, emerged as local civic bodies that brought together residents from a single village or several neighboring villages who were already involved in agricultural production or used the same irrigation and water control system. In towns with agricultural business and commerce, public temples and shrines were also established devoted to worshiping a common god or spirit according to the tradition of “separating the incense.”23 In ordinary times, these places of worship served to develop closer emotional bonds among the villagers as they gathered together to revere the local spirits and engage in other religious activities. But when incidents or other occurrences demanded their attention, the temple then was a public forum where residents could hold meetings and discuss the situation.

Based on available research, by the early nineteenth century many influential landlord families on Taiwan began to accumulate substantial wealth. They built shrines and temples and purchased land to support ancestral worship. They also frequently purchased official ranks (the lowest being the imperial rank of chien-sheng) as a quick way to bolster their family’s social status. Ts’ai Yuan-chie’s study of two of the most influential landlord families in the central and northern regions of rural Taiwan—the Ch’ens of T’ou-fen and the Lins of T’ao-yuan—revealed many similarities in their paths to local leadership. The first member of the Ch’en family, a man by the name of Ch’en Feng-ch’iu (1761–?), came to Taiwan in 1774 and engaged in agricultural work for many years. Not until the age of forty was he able to save enough money to get married. His eldest son received some education but also did not get married until the age of thirty-nine because of the generally impoverished conditions of the family. Thus it was not until the third generation that Ch’un-lung (1834–1903) was able to purchase a lease on agricultural land and collect rent. It was also at this time that the family became involved in the sugarcane processing and wholesale grain businesses from which they made a sizable fortune and gradually became a influential local landlord family. By 1871, the third-generation Ch’en had purchased a chien-sheng imperial title and in 1892 he became the temple headman and local leader.

Another example of an influential landlord family were the Lins from Lan-chu town in T’ao-yuan county. Originally tenant farmers, they gradually moved up the socioeconomic ladder and became the wealthiest family in the area. Their ancestor, Lin Wen-chin, had come to Taiwan in 1745 and worked for thirty years as a tenant farmer. By 1775, he had saved enough money to buy 19 chia of land, which he divided up and leased to other tenants in return for rent. Lin T’ien-ts’ih (1806–1878) of the third generation expanded the family’s operations from agriculture into the cloth dyeing business and the rice trade. The family reportedly collected one thousand tan of rent per year, which propelled them into the position of local leadership. In addition to donating money in exchange for an imperial title, the Lin family also built a mansion in 1873 to symbolize their growing social status.24 In short, both the Chens and the Lins spent two or three generations at hard work in agriculture, in addition to becoming involved in the rice retail and cloth dyeing business, before they could achieve their wealth and high social status. In so doing, they were able to accumulate the funds necessary to set up their own clan organization. In a similar manner, in the nineteenth century two influential families in Hsin-chu town—the Chengs and Lins—also worked for two or three generations to accumulate the wealth necessary to purchase imperial titles and to expand their social influence through marriage arrangements. In this way, they were gradually able to assume the status of country gentry.25 In all, these examples demonstrate that, for local influential families to climb up the social ladder and achieve leadership positions in local society, they not only had to accumulate wealth but also had to expand their social status and reputation, especially through calculated marriage arrangements. This helped them establish extensive political and social influence and acquire long-term reputation and respect.

Many of the influential families also used the opportunity afforded by the government’s suppression of local uprisings and riots to win military awards and merit. For instance, following the quelling of the 1786 Lin Shuang-wen uprising on Taiwan, sixty-seven influential family leaders won official recognition and received military citations. Among the sixty-seven, forty were representatives from low-level gentry families at the wu-sheng or provincial (chu-jeri) rank and the other twenty-seven were common citizens. In 1790, fifty-six people received awards after the Ch’en Chou-ch’uan uprising was suppressed, thirty-nine of whom were local leaders who had never before received official honor or rank. In 1862, following the Tai Ch’ao-ch’un incident, although only ten representatives from influential families received awards, even fewer commoners received such recognition, numbering only six.26 All this demonstrates that, by becoming involved with government efforts to suppress local uprisings, many influential families were able to use their clan power to set up local militia for self-defense and to protect their families.

However, not all landlord families were able to become local strongmen by building up their own militia. In fact, the majority of local leaders were merely representatives of landlord families with no such power at their disposal. In most cases, they simply donated money in return for low-ranking imperial titles while they generally avoided establishing their own armed militia. The experience of the Lins of Wu-feng with their personal militia was instructive in this regard since they had been punished by the government for misusing their forces despite their considerable social and political influence. In order to analyze the multifaceted situation of the local elite structure on Taiwan, we therefore examine three separate examples of prominent families on the island. They are the Chang family of the Taipei basin area, the P’an family of the P’ing-p’u aborigine tribe in central Taiwan, and the Lins of Wu-feng. These three families lived in separate areas of central and northern Taiwan and made a fortune from agricultural work. The Chang family came to Taiwan relatively early and were a typical example of a family with considerable entrepreneurial spirit. The P’ans were a leading family in the Pazeh tribe. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they established a cooperative relationship with the government on the strength of their personal military power and strategic calculations, from which they gained considerable landholdings that were then leased out. As for the Lins of Wu-feng, they were a prime example of a landlord family that in the nineteenth century had emerged as local strongmen. By leasing out their extensive landholdings, the Lins made a fortune, which they used to set up and lead a local militia made up of people from several villages. In subsequent years, the Lin family was awarded by the government for their effort in helping to suppress local uprisings. In this way they managed to enter the bureaucratic system and also became the most powerful family in central Taiwan.

The Chang family was originally from Chin-chiang county, Ch’uan-chou, Fukien province. In 1702, Chang Shih-hsiang (1673–1732) cheated on his application for the civil service exam by claiming to be from Hui’an county. After he was reported to the authorities, Chang decided to cross the strait and seek out new opportunities on Taiwan. Initially, Chang Shih-hsiang continued to seek personal fame while at the same time he invested in the land reclamation business and helped to open new lands in the Yun-lin area of southern Taiwan. Around 1720, through an introduction from an acquaintance, Chang leased a substantial amount of uncultivated grasslands from the Mao-erh-kan tribe of the P’ing-p’u aborigines and as “farm manager” hired tenant farmers to develop the land. Relying on the practice of “Han management of aboriginal property,” Chang established his management rights over the land, from which he earned considerable wealth and capital. Later, Chang’s sons and grandsons used these gains to invest in various irrigation and water control projects. In 1735, Chang’s eldest son, Chang Fang-kao (1698–1764), constructed the “Ta-yu-chen” water control system, which opened up hundreds of chia of farmland to irrigation. On average, one chia of land generally yielded two tan of rice. The success of these land development measures and water control projects enabled the Chang family to accumulate large amounts of wealth in a rather short period of time and to become local strongmen.

In 1751, the fourth son of Chang Shih-hsiang, Chang Fang-ta (1715–1764), used the gains from the family business in central Taiwan to invest in the Hsin-chuang plain near the upper reaches of the Tan-shui river in the Taipei area. He also established a reclamation company called Chang-wu-wen along with two other men named Wu Lo and Mao Shao-wen. Through this partnership, the three jointly invested and managed their landholdings. In 1755, the Mao family asked to withdraw from the partnership because of the lack of funds, leaving Chang and Wu to continue to manage the remaining lands on a share basis. Ultimately, Chang formed his own Chang-pi-jung company while Wu set up the Wu-chi-sheng company. From that point onward, the two families managed their land-holdings and tenants separately.27

On the basis of the experience of these three families in setting up and then abolishing a management partnership, one can learn a great deal about the entrepreneurial spirit of the landlord class in its early formation. In order to establish control over large tracts of land, they each invested considerable funds through a partnership-type organization. The primary purpose of such a company was to earn profits and collect rents through the leasing of land. In other words, they invested primarily for the purpose of collecting rent but without bringing about major improvements in agricultural technology and production methods. For that reason, they generally allowed the original tenants to continue to cultivate the land and to maintain a steady level of rent payment. On the one hand, such a leasing system encouraged their tenants to invest to improve the productivity of the land over the long term. On the other, the landlords avoided spending great amounts of their own money in search of new tenants. Such a tenant-leasing system that commingled the management of capital investment and protection of tenant rights guaranteed the security of rural land rights while also promoting land and agricultural development. In fact, one can argue that this was one of the primary reasons for the rapid development of agriculture on Taiwan.

At the same time that Chang Fang-ta expanded his agricultural business, Chang Fang-kao started his land business in a nearby village known as Hsing-chih (later renamed Hsin village). In 1753, he established his own Chang-kuan-fu agricultural settlement and purchased cultivation rights on a large piece of grassland from the P’ing-p’u aborigines. Both parties agreed that the Chang family would pay rent to the aborigines on a regular basis in return for the right to hire tenants or transfer cultivation rights. In accord with common practice, these rights granted to Chang conferred on him the status of “landlord.” The rights of the aborigines were limited to collecting rent as they were prevented from interfering in the management of the farm, even though the tribe retained the superficial status of landlord. Once he gained cultivation rights, Chang hired more than fifty tenant farmers and opened up more than 130 chia of land. With one chia yielding on average 8 tan of crops, the family collected 1,000 tan of rent a year, which back then constituted a huge fortune.28

Besides developing land and collecting rent, Chang also invested huge sums in developing irrigation networks and water control projects. In 1757, the Changs established a partnership with the Wu family to build a water control project in Fu-an-chen about eight li in length. However, during the summer two years after its construction, a huge rain storm virtually destroyed the entire project turning more than 200 chia of land into a swamp almost overnight. Even more unfortunate was that before this project was even completed, a homesteading family named Liu living in a nearby area received the rights from the local government authority to build their own water control-irrigation system on Chang family property. Two years later, the Lius successfully constructed their own Wan-an-p’o hydro dam with a capacity to irrigate up to 300 chia of farmland. The Chang family sued on several occasions over the Liu family’s intrusion onto their land, but were ignored. It was not until 1764 when the eldest son of Chang Fang-kao, Chang Yuen-jen, successfully passed the provincial scholar (chu-jen) exam that the Chang family was able to force the local government to deal with the case. The result was that in 1765 the Chang and Liu families signed an agreement in which the Liu family would pay the Changs 600 tan a year in water rent (shui-tzu) as compensation for using Chang family land. The Chang family, in turn, allowed the Liu’s dam to remain in place. At the same time, the two families agreed to share the available water resources to irrigate their lands.

From this experience, one can tell that, by the eighteenth century, partnerships were widely employed by the landlord class as a way of investing in the development of agricultural land. On the one hand, they leased land from the aborigines thereby gaining management rights over the land. This, in fact, was the method the Chang family used to acquire the right to the manage lands, which yielded them considerable wealth. On the other, landlords such as the Chang family subleased their cultivation rights to other tenant farmers. Landlord families also invested heavily in irrigation and water control systems evidently in the belief that relying on rich water resources ensured continuous growth in the productivity of the land. Since control over water resources effectively guaranteed continued control over rent collection, many wealthy landlord families invested huge sums in water projects. However, the disastrous experience of the Chang family described above also made it apparent that construction of such projects was very risky.

Another important factor in the rise of the Chang family was their reliance on a relative who had achieved the official provincial rank of chu-jen in the Ch’ing bureaucracy. Although at the lower rung of the official hierarchy—since he was far from the center of political power—his position still carried great weight in the local rural power structure. This, in fact, is why many wealthy landlord families encouraged their family members to pass the scholar-official exams or to donate money in exchange for an imperial title.

The P’ing-p’u are an aboriginal tribe living in the plains area along the coast of Taiwan. After the island was taken over by the Ch’ing, the government divided the aboriginal tribes into two groups: those in category one were known as “civilized aborigines” (shu-fan), that is, aborigines who accepted the authority of the Ch’ing and who willingly paid taxes based on the number of people per household; those in the other category were referred to as “uncivilized aborigines” (sheng-fan), tribes that refused to accept the authority of the Ch’ing. According to Ch’ing practice, before their naturalization, the shu-fan donated land to the Ch’ing court and in return received land on which they could hunt and make a living. Since this group was willing to pay taxes to the Ch’ing government and exhibited considerable bravery in traveling over long distances, the Ch’ing recruited them to deliver government documents across great distances and to assist its military forces in suppressing local uprisings. In return, the Ch’ing adopted policies to protect aborigine rights including prohibitions against any Han from occupying aboriginal land. However, from the beginning of the eighteenth century onward, many shu-fan enticed Han settlers into their homelands to help in reclaiming and converting barren land into cropland. This practice of “Han management of aboriginal property” was a way to circumvent official regulations, which had prohibited the Han from occupying aboriginal farmland. In pursuing this surreptitious course, the aborigines were able to retain control over their land rights while also collecting rent or lease fees. This approach was beneficial to both the Han and the aborigines and was especially popular in the western aboriginal regions of the island. Throughout the Ch’ing dynasty, quite a few tribes used this method to develop large amounts of land, which ultimately resulted in the formation of an aboriginal landlord class.29 The P’an landlord family discussed below was, in fact, the most outstanding example of such an aboriginal landlord class.

The Anli tribe belonged to the Pazeh branch and was referred to as the Pazeh people. The P’ing-p’u consisted of four large tribes: the Anli, P’u-tz’u-li, Alishi, and Wuniulan. Since the Anli tribe had for many years led the other tribes, it was generally considered the representative of them all. During the mid-eighteenth century, when the Anli tribe was at the height of its influence and power, it controlled considerable land rights in the northeast region of the central Taiwan basin and the hilly region between Ta-chia-hsi and Tien-hsi. The Anli were also the largest tribe among the P’ing-p’u aborigines.30

As early as 1699, the Anli people accepted the authority of the Ch’ing by helping government forces to suppress the anti-Ch’ing uprising among the T’un-hsiao tribe in the north-central region of Taiwan. Later, in Chu-lo county (subsequently renamed Chia-yi county), the district magistrate (chih-hsieri), Chou Chung-hsuen, realized that many Han had moved into and taken control of the grasslands north of Ta-tu-hsi and Ta-chia-hsi, creating a situation in which the Han “lived among the fan, married fan women, and adopted fan children.” In order to stave off conflict and any acts of revenge between the aborigines and the Han, Chou put the local leader of the Anli tribe by the name of A-mo in charge of all P’ing-p’u affairs in the central region of the island. Then in 1716, the former provincial governor of Fukien province, Sha Mu-ha, conducted an inspection tour of Taiwan after which he suggested to the governor-general of Fukien and Kuangtung, Chue Lo-man-pao (a Manchu), that the Anli people be naturalized. The Anli were therefore recognized as shu-fan and submitted as tax 50 hides of deer (equivalent to 12 Hang of silver). At the same time, A-mo recommended that a Han man by the name of Chang Ta-ching (1690–1773), who was of Kuangtungnese origin and spoke the aboriginal language, be put in charge of the general affairs of the aborigines.

Around 1710, the Anli tribe consisted of 422 households, totaling 3,300 people. (Based on the Han household registration system, the average number per household was eight people.) Their life-style involved slash-and-burn agriculture along with fishing, and they were generally unaware of the Han method of wet-rice production. However, after being naturalized, they applied for permission from the government to engage in the long-term cultivation of the land. In 1732, the Anli tribe obeyed official demands to send their forces to assist the Ch’ing in suppressing an uprising among the Ta-chia-hsi tribe. Following this action, once the government had declared as “traitorous property” all the holdings on the grasslands of those tribes that had been involved in the uprising, ownership of these territories in the northeast area of the central Taiwan basin was transferred to the Anli. Later, with the assistance of Chang Ta-ching, the Anli began large-scale wet-rice production.

Chang Ta-ching was originally from Ta-p’u county, Kuangtung province, and in 1711 crossed the strait to Taiwan, where he became involved in agriculture. In 1716, he gained the trust of the Anli by providing them with medicine. Later, as noted above, he was chosen to take charge of Anli affairs because of his fluency in the tribal language. He was put in charge of their financial dealings and also handled official Ch’ing documents and decrees directed to the Anli. In 1732, after the Anli had acquired land from the Ch’ing government, Chang helped the newly appointed native headman by the name of Tun-tzu (a grandson of the general headman A-mo) in opening up and developing the grasslands. On the one hand, Chang encouraged a great number of friends from his hometown on the mainland to invest in and develop barren land along the lines of “Han management of aboriginal property.” On the other, in order to speed up the process of turning dry land into wet-rice paddies to increase production, Chang recommended that the six wealthy families of Lu-kang (generally known as the “six-family enterprise") sign an agreement with the Anli tribe that “divided up land in exchange for water” and committed both sides to joint investment in water irrigation projects. In line with this agreement, the Anli turned over large tracts of land to these wealthy families in exchange for capital and the necessary technology to build an irrigation system. Relying on the strategy of “Han management of aboriginal property” and “dividing up land in exchange for water,” the Anli grasslands were successfully converted into rice paddy and sugarcane fields from which the Anli collected a fixed amount of rent every year. It was these benefits from land rights that enabled the Anli people in the eighteenth century to accumulate substantial wealth, making them the most power aboriginal landlords in central Taiwan.31

Based on the traditions of the Anli tribe, all the lands of the various tribes were subject to the authority of the “tribal headman.” In 1747, since the tribal headman at that time had become old and infirm, Tun-tzu was invited to take charge of the tribe’s landed properties, which he divided into two categories— “common” and “private commercial” land—as a way to facilitate land management. Common lands were put under the control of the native family patriarch, who oversaw development of these lands and collected rents that were used to support the affairs of the entire tribe. The private commercial land was made the responsibility of individual households. But if any member wanted to transfer or sell their land rights, this required the approval of the native family patriarch of the tribe for the transfer or sale to be effected.

Tun-tzu used the method of “Han management of aboriginal property” to manage the common lands. Based on Ch’ing records from the year 1770, there were 290 chia of common lands, from which 4,600 tan of rent was collected annually. The private commercial lands belonging to Tun-tzu also yielded about 4,000 tan of annual rent, on which he relied to accumulate the wealth necessary to follow the traditional gentry landlord’s life-style of cultivating a broad social network. In ordinary times, he used part of the profit from the rent collected on the common lands to buy gifts for civil officials and to provide donations to the government to assist it in suppressing uprisings. In addition, Tun-tzu often supported the construction of local temples in villages and various communities and participated in religious activities. He also developed the hobby of growing orchids and even went so far as to hire a gardener from the mainland to cultivate them. In 1758, at the suggestion of Ch’ing officials, he adopted “P’an” as his surname. As was apparent from his approach to agricultural management and his social-cultural activities, Tun-tzu had become very sinified and had also established himself as an influential landlord family.

Before Tun-tzu passed away, he made out a will that divided his property into two parts. The P’an family common lands, which yielded about 1,700 tan per year, were devoted to venerating the family’s ancestors and paying for family-related expenses. The other parcels of land were bequeathed to the children and grandchildren of his two wives. Each family received rental property worth 4,500 tan. Also, Tun-tzu’s titles as headman, director, and others were also inherited by his two sons. His eldest son, P’an Shih-wan, was not only put in charge of the Anli common lands but was also temporarily appointed as director. In 1786, during the Lin Shuang-wen uprising, P’an Shih-wan led his militia to assist the Ch’ing suppression of the rebels and was awarded a class six decoration. The second son, P’an Shih-hsing (1761–1818), also purchased an imperial title for himself in 1786 and titles for his two sons in 1811 and 1814. The practice of donating money in exchange for an imperial title indicates that, before the early nineteenth century, the P’an family maintained its ownership of substantial amounts of property while also taking full advantage of the purchase of imperial titles to maintain the social status of the family.

During the third generation of the P’an family, however, its social situation rapidly deteriorated along with the rest of the P’ing-p’u aborigines. The eldest son of P’an Shih-wan, P’an Chin-wen (1766–?), was, in fact, the real son of a Han family who had been adopted by the P’ans and was in a position to inherit P’an family property. From 1796 to 1803, he was appointed the headman of the Anli tribe. Unfortunately, P’an Chin-wen began to spend money wildly and was perpetually in debt and could make a living only by pawning family property. An extravagant life-style was also the culprit in driving P’an Ch’un-wen (1781–?), a son from P’an Shih-hsing’s second wife who was of pure Anli lineage, deep into debt. By the 1820s, the heirs of the P’an family had thus lost much of their land to Han bankers, something that also occurred with the majority of P’ing-p’u aboriginal landlords. The result was that, by pawning off their land rights, the people were gradually reduced to poverty.

Since Johanna Meskill published her 1979 work on the Lin family, academics have generally considered the Lins as the typical example of how a border area landlord had become a member of the urban gentry during the Ch’ing dynasty.32 Indeed, the Lin family was not only an important family from Fukien that had come to Taiwan and opened up lands and earned enormous wealth, it also controlled a very large militia comprising the family’s tenant farmers. In the 1850s, the Lin family donated money to the Ch’ing while the family militia assisted Ch’ing troops in suppressing the forces of the T’ai-p’ing Heavenly Kingdom on the mainland. As a result, the Lin family was promoted to the position of provincial commander-in-chief in charge of land forces. Indeed, the primary reason the Lin family was able to develop from a wealthy farming family into urban gentry was that Taiwan was far from the center of Ch’ing control, which made it possible for powerful families like the Lins to establish their militia forces.

In recent years, Huang Fusan has examined more original data and materials on Lin family history, providing us with a somewhat better understanding of the twists and turns in the rise and fall of the Lin family. The success story of the Lin family began with the founding father, Lin Shih (1729–1788), who came to Taiwan in 1746 and opened up agricultural lands near the central mountain region. As with most early homesteaders, Lin Shih acquired grasslands from the aborigines and then returned to his hometown on the mainland to hire friends and relatives to assist in developing and establishing a community in which the Lins were the primary members. Once they became wealthy enough, the Lins got involved in the rice trade and rural loans. Together, their various investments yielded as much as 10,000 tan in profits every year.33

Unfortunately, as a result of the uprising led by Lin Shuang-wen, a member of the Lin clan, the Lins were almost completely destroyed. Living in the same community near Ta-li-fa, Lin Shuang-wen had called on Lin Shih for assistance. In 1786, as the leader of the Heaven and Earth Alliance, Lin Shuang-wen joined with other secret societies such as the T’ien-ti [untranslatable, characters different from Heaven and Earth Society—Eds.] and the Thunder Alliance (Lei kung hui), and became involved in armed conflicts. Later, to avoid being arrested by local officials, Lin sparked an uprising and took over the county seat of Chang-hua. In 1788, however, Lin was captured and killed and had all his properties, many linked to the Lin family, confiscated by officials. Since Lin Shih was considered a relative of a traitor, he was imprisoned and more than 400 chia of his farmland was confiscated, causing great suffering for the entire Lin family. Eventually, he decided to move to Wu-feng and start all over again in making his fortune.

The second-generation Lin, Lin Chia-yin (1782–1839), after considerable effort, was very successful in reestablishing the family. Making good use of the mountainous environment around Wu-feng, he purchased cultivation rights from the aborigines and hired tenant farmers to cultivate the fields. Also, seeing the increasing number of Han in the area who were in need of timber to build houses and of charcoal for cooking and heating, Lin started a thriving timber and charcoal business, which made him a huge fortune. According to Huang Fusan’s research, Lin Chia-yin’s investment in farmland and his timber/charcoal business yielded 4,000 tan of profit every year, which enabled the Lin family once again to assume the status of influential landlord.

The first two generations of the Lin family not only accumulated large sums of wealth and established an influential family-clan network, but also recruited their tenant farmers into their personal militia. As the leader of the Lin family during the third generation, Lin Ting-pang had learned martial arts as a youth and was frequently involved in fights in town. Later, he took charge of training the family militia and handling the mediation of family and clan conflicts over such matters as money and marriage. At that point, Lin Ting-pang’s living situation had become quite different from that of his ancestors. The Lin family lived in a densely populated area with quite a few influential family clans among whom there were all kinds of conflicts over property rights and water resources. For instance, Lin Ma-sheng of Ts’ao-hu village was very powerful and he himself was the head of a local militia and a VIP in the local community. Lin Chia-yin’s family was not as powerful and influential as Lin Ma-sheng’s. Moreover, since Lin Chia-yin lived close to the mountains, some of his tenants traveled into the mountain region surreptitiously to cut timber, which the aborigines deeply resented since it disrupted their hunting. Given their situation, the Lin family, like other farmers, learned martial arts and carried farm tools, knives, and guns as weapons. Once an incident occurred, they would gather together and rush to confront the enemy. In 1850, a member of Lin Ting-pang’s clan was suspected of raping a housemaid of Lin Ma-sheng’s, which provoked a huge fight between the two families in which Lin Ting-pang was killed by one of Lin Ma-sheng’s bodyguards. Since the murder involved two influential clans, local officials took considerable time to solve the case. Ultimately, the Lins spent large sums of money to bring the suit all the way to the central yamen in Peking, a process that took seven years.

The fortunes of the Lin family improved during the fourth generation of Lin Wen-ch’a (1828–1864). At the time of Lin Ting-pang’s death, Lin Wen-ch’a was already twenty-three years old. During his youth, Lin Wen-ch’a had enjoyed playing with guns and knives and admired the historical heroes Kuan Yu and Yueh Fei. Lin himself was famous for being a born fighter and so after his father was killed, Lin Wen-ch’a planned to lead the whole family in an act of revenge. Prevented from taking action by his mother, Lin planned his revenge in secret. In 1851, he led two hundred family militia and killed the guard who had murdered his father. Just to ensure that Lin Wen-ch’a’s family would not carry out more revenge, Lin Ma-sheng reported the incident to the Taiwan prefect and even to the Fukien inspector and the Fukien-Chekiang governor-general, which ultimately led to Lin Wen-ch’a’s becoming wanted by the police.

During the period of conflict between Lin Ma-sheng and Lin Wen-ch’a, many uprisings broke out in Taiwan while at the same time the coastal areas of Fukien were threatened by T’ai-p’ing forces. In 1853, when Lin Mu of Feng-shan county learned that T’ai-p’ing troops had captured the city of Nanking, he called together the local heads in Chang-hua and Chia-yi and organized an uprising. It was said that from Tainan prefecture to Feng-shan county, tens of thousands of households joined in the uprising while the number of Ch’ing soldiers stationed in the prefect city was no more than three thousand. Although the uprising lasted for only four months or so, it revealed the weakness and corruption of security in Taiwan. Earlier, Hsu Tsung-kan, who was the Taiwan intendant of the circuit from 1847 to 1854, pointed out that there were too many uprisings and conflicts occurring on the island. Since the government could not rely on its troops to effectively maintain order, Hsu was left with no choice but to encourage local influential family clans to train village residents to assist official troops in suppressing local uprisings and conflicts. In 1853, a large number of property owners in Fukien had formed the “Small Sword Society” (Hsiao tao hui) to oppose attempts by tenant farmers to avoid paying rent. Once the two sides began killing each other, the Small Sword Society launched an attack on the yamen and killed local government officials and for a while occupied Amoy as its base. Later, after being encircled by government troops and broken up, some members of this secret society escaped to Taiwan, where they attempted to occupy port cities and towns. Ch’ing troops stationed in Taiwan were obviously unable to put down their rebellion, and so someone recommended that Lin Wen-ch’a take control of the situation. In this way, he could finally make up for his earlier crimes against the Ch’ing. Lin Wen-ch’a did a good job, launching a successful counterattack against the Small Sword Society. In return, Lin and his militia were awarded a class six decoration, which opened the door for his family to enter the formal bureaucracy. Later, Lin Wen-ch’a donated a considerable sum of money to support government forces and was appointed by officials to head the Ch’ing’s mobile forces.

As a result of Lin Wen-ch’a’s outstanding performance, the officials gained trust in him, and, given that the situation in Taiwan had not yet stabilized, he was ordered to go to Fukien and Chekiang provinces to assist the Ch’ing government in its effort to suppress the T’ai-p’ings. From 1859 to 1863, Lin Wen-ch’a led three thousand soldiers known as the “brave heroes of Taiwan” in winning a number of victories, which resulted in his eventually being promoted to several positions including commander-in-chief of Fukien troops, the highest position ever attained by a Taiwanese during the Ch’ing dynasty. This position also ensured that he became an influential landlord and country gentry.

During the period when Lin Wen-ch’a fought battles on the mainland, a large-scale uprising led by Tai Ch’ao-ch’un broke out in Lin’s hometown in Taiwan (1862–1865). The Tai Ch’ao-ch’un family was a prominent clan in central Taiwan with three generations as renowned and wealthy landowners and with prominent positions in the military defense system for northern Taiwan. Before the uprising, his elder brother, Tai Wan-sheng, had joined with other wealthy landlords in forming secret societies similar to the Land God Society (T’u ti kung hui) and the Eight Diagrams Society (Pa kua hui). The purpose of these societies was to protect property and water rights and to resist rival clans. Tai Wan-sheng himself organized the Heaven and Earth Society to train militia. Many landlords and wealthy households thought that since the government troops were unable to provide armed protection of their cultivation rights and personal safety they had no choice but to join Tai’s organization. It was said that, at the height of its influence, ten thousand or so people were members of the organization while Tai Wan-sheng became the leader of all the local strongmen.34