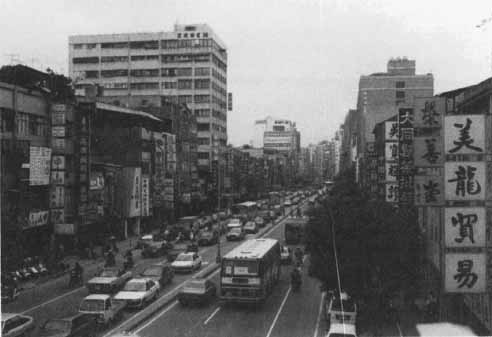

Chengde Road in Taipei.

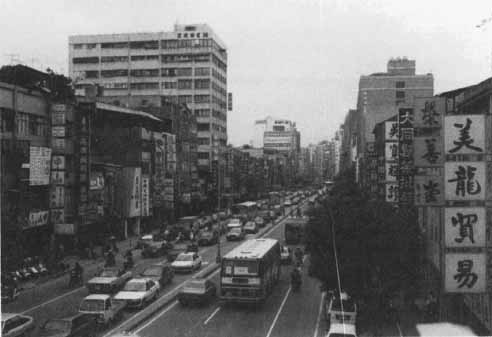

Chengde Road in Taipei.

This chapter examines the large-scale economic and societal changes that have occurred in Taiwan since 1971, such as the development of a new, more activist middle class, and a new urban environment. These new forces and conditions generated sociopolitical pressures that forced the regime to reform itself and that changed the pace and nature of political change and democratization. The chapter begins with an examination of the development of the export-oriented industrial economy that transformed the face of the island, made it a major player in the world economy, and forced the pace of both social change and political evolution.1 The discussion then turns to the multileveled and multifaceted societal evolution that gave birth to an educated, articulate, and politically conscious middle class that would use its new-found power to push for changes in Taiwan’s political structure (examined in Chapter 15).2 The conclusion explores the process of urbanization that changed the face of the Taiwanese landscape.

The first stage of Taiwan’s dramatic economic transformation took place from the early 1950s to the early 1960s. Formal planning structures were put in place, and Chinese economic specialists, with input and advice from American advisers, developed an import-substitution industrialization strategy to prevent the outflow of capital and to lay the foundation for further development. During the first phase of import substitution, certain products with potential value as exports were produced. Processed agricultural goods, for example, led the way here. Sugar and rice became the island’s major exports. However, another key product that was not a foodstuff had potential in the world market—textiles. By 1959 textile production had increased 50 percent over earlier levels and exports of textiles increased 500 percent. In 1960 textile production increased yet another 19 percent and exports of textiles increased 74 percent over the previous year. Over the course of the 1960s, textiles would become Taiwan’s single-largest export product.3

Before going further, we must examine the changes in another important sector of the economy from the 1950s to the 1990s—the rural sector. While many people left the countryside, agriculture remained important. The land reform measures gave many farmers greater opportunity, and they took full advantage of it. Rice continued to be the major crop, but after the 1970s there was also considerable diversification as new methods and new crops were introduced.4 American and Chinese agricultural specialists worked hard to bring these developments about, teaching the farming population the new methodologies and promoting the introduction of new strains and new crops. Increasingly, farming became more commercialized.5 Furthermore, better methods of flood control opened new lands or those that were formerly dangerous to use—primarily the river beds of the major central and southern westward-flowing rivers—for cultivation. In real terms, over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, agricultural output increased. However, by the early 1970s the rate of increase had slowed down, and in 1975 one could see a decrease in the growth of farm crops and related products. The general decline continued into the 1980s.6

This decline forced some to move into new forms of agricultural production. One important new crop was flowers. While floriculture has been practiced on the island since the 1600s, only since the 1970s have Taiwanese steadily developed this industry. By 1990, 6,300 hectares were devoted to growing flowers. One good reason for this shift to flowers was that in 1990 a hectare of rice produced U.S.$3,000, a hectare of flowers produced U.S.$24,000. As a result the island has become a major exporter of a wide variety of flowers and other decorative plants, finding major markets in nearby Japan, the United States, Singapore, Hong Kong, and that most famous of flower-producing nations, the Netherlands (which controlled Taiwan during the early seventeenth century). Japan was the largest market for live flowers, while the United States bought dried flowers and potted plants. The Netherlands bought potted plants as well as young sprouts that could easily be raised in Dutch greenhouses. The Taiwanese flower industry competed with those in Southeast Asia, but those who observed the industry believed that it would continue to meet the challenges with new varieties and with products of high quality.7 Certainly for the farmers, this new crop proved a boon and kept people on the farm with the hope of good salaries and continued expansion of production.

These changes, while important, could not stop the inevitable decline of the agricultural sector. While 13 percent of the work force was involved in agriculture in the early 1990s, agriculture accounted for only 4 percent of the gross national product. Furthermore that work force was aging. Adding to the pressure on those farmers who remained was the fact that agricultural land near major suburbs was needed for new highways, rapid transit systems, or new housing complexes. Given the straits in which farming families found themselves, the money offered by the government was too high to turn down. It was also increasingly clear to farmers that agriculture was no longer the fundamental sector in the national economy. They experienced a liberation of sorts and felt emancipated from their static way of life. Because of this, the very value system of the farmer was changing. And this is clearly reflected in the attitudes toward the land itself. Huang Chun-chieh, a historian of modern Taiwanese agriculture and the age of the Chou philosophers, puts it this way: “Land was no longer considered ‘sacred’ family property; rather, it became a ‘secular’ transferable commodity.”8

The development of aquaculture provided rural areas with a much-needed boost. Those holding property in low-lying areas along the coast now found new opportunities. Fish ponds and the raising of carp and other seafood had long been a part of the rural economy, but, on Taiwan, the new technologies were brought to bear on this sector as well as on agriculture. In the fish ponds that dot the landscape near the sea are grown many different fish and shellfish. Milkfish, a staple in soups and congee (rice porridge) for centuries, are grown in brackish or freshwater ponds in the southern part of the island near Tainan. Eel (man), brought by the Japanese in the early 1950s, are raised in freshwater ponds and prepared roasted or smoked. Tilapia is another popular fish grown in brackish or freshwater ponds. Carp, the classic pond fish, continues to be popular, especially during the lunar new year, and is usually served braised or steamed. Mullet are raised only for their roe, which are dried and roasted. Grass shrimp are raised in brackish ponds in southern Taiwan and are prized as a delicacy, as are oysters. Finally, sea cucumber, a basic ingredient in many Chinese seafood dishes, are now being produced.9 Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, the industry made notable gains, in part because of the government’s willingness to set up research institutes that worked with those involved in the aquaculture industry. However, the shift to the use of fish ponds has created problems as well, including salinization and a sinking of the land due to the drainage of water from the existing water table. Industrial pollution of the water sources is seen as another problem, one with no easy solution. Moreover, the industry reached a point in the 1990s at which it was suffering from its own success, with certain species flooding the market. The solution to this problem is shifting production to higher-quality types of fish, which can bring higher prices from the consumer. In this realm of rural life, Taiwanese are making use of the readily available resources of brackish water and the centuries’ old skills of the fish pond farmer to sustain and increase this industry’s growth.10

The government realized from the beginning that import substitution was not an end in itself but simply a starting point for a more sophisticated and more realistic economic strategy. From the mid-1950s to the end of that decade, certain measures were taken to move the economy to this second, more sophisticated stage of development. In 1958 came the implementation of a monetary exchange formula that created a more unified exchange scheme. A second step was taken in 1960, when a five-year tax holiday was declared for new ventures in certain types of manufacturing. The income tax was exempted for redistributable (reinvested) profit and was also reduced for proceeds gained through export. Interest rates were also raised on savings, which may have led to a dramatic jump in the percentage of funds being saved by households—from between 5 percent and 8 percent from 1952 to 1962 to 13 percent in 1963. Such additional funds provided industry with additional seed money. The final step in the implementation of the new economic strategy came in 1966, when export processing zones were set up. Such zones had streamlined administrations and support from the power utilities and were developed to foster the export manufacturing sector.11

Each of these decisions, as the architects of the new strategy such as K.T. Li and as economic analysts such as Wang Chi-hsien have informed us, were designed to redirect the economy and fit the Republic of China into a worldwide, Western-directed economic system. Taiwan now had increasingly well-educated workers (though these workers were still paid little relative to their Western contemporaries), power and transportation infrastructure, and security guaranteed by both an American military presence and the existence of a now well-trained and well-armed military force. It was considered one of the five best places to locate an export-oriented economy. The island was resource poor but did have both a skilled and unskilled labor force, a stable monetary system, and a regime that was in control of the labor force and had a say in the role of the private sector.

During this preparatory period, government planners working with officials at the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) had decided to exploit the island’s major resource—its people. Those officials who represented the regime to foreign investors—at this point both Westerners and Japanese—could also offer the foreign industrialists a host of incentives—special economic zones and other attractive perks. They could guarantee, for example, that if the goods these manufacturers produced were intended only for markets outside Taiwan, then that concern could be wholly foreign-owned. If, however, these firms involved themselves in Taiwan’s domestic market, then Taiwanese would have to own 50 percent of the company and Taiwanese would have to supply a certain percentage of the components of the product that was being assembled and sold in the Republic of China. This became the situation in the 1970s and 1980s as the effects of economic growth were felt more and more by larger numbers of people on the island and as the demand for readily available, cheaper, and better-quality consumer goods became widespread. The jointly established Taiwanese–American or Taiwanese–Japanese assembly plants that were set up were the most striking examples of this second pattern of foreign industrial investment.12

During the 1960s and for many years thereafter, it was the electronics industry that was most attracted to Taiwan and saw its potential as a processing or assembly center. This industry was important in several ways. First, it was not in any way indigenous to the island—there had been no tradition of producing products at this technical level. Second, it was not developed, at least at first, to meet the needs of local consumers. Finally, it was an industry whose owners supplied everything it needed from outside the country except a hard-working and increasingly skilled work force. The decision of the Republic of China’s technocrats, a decision made with the help of U.S. AID officials, proved correct. As Wang and others have shown, major electronics companies in the United States, the Netherlands, and Japan were attracted to the incentives offered by ROC officials. These companies produced products that were compositions of components or component modules. These could be shipped easily from suppliers in other nations or, later, from other areas on Taiwan because of their light weight. Furthermore, while the design, development, and processing of key components was both technology-intensive and capital-intensive, the actual assembly of components could be done by hand by a low-skilled labor force for low wages. When one combined the nature of the electronics industry as it stood at that point in the 1960s with the willingness of a government to set aside land for industrial development, tax rebates, and the extended tax holiday, one came up with a package deal that the major players found irresistible.13

The newly arrived firms found a low-cost, dedicated, and readily trained work force at their disposal, a work force that—given the totalitarian nature of the Taiwan government and that state’s control of labor unions—was not then able to organize itself and confront potential exploitation at the hands of the foreign owners. From 1965 to 1970 alone, the new industries helped create new growth in the work force and, in turn, made possible a dramatic drop in unemployment rates.14

The rise in employment in the industrial sector meant that within a relatively short time wages were able to rise. This rise in wages was accompanied by a corresponding rise in productivity, for the various educational reforms, including the single most important change in the educational process—the increase in the number of years of free public schoolings—was creating a better-trained and more skilled labor force that was able to cope with the more technical demands made upon it. Furthermore, as the export orientation spread to other industries, new actors, not just the large-scale international firms, began to enter the picture. As a result the industrial structure that had evolved began to change. Decentralization became an accepted pattern. Smaller-scale industrial firms began to produce more specialized goods in an increasingly fragmented system. This alternative structure, one that was open to low-level and small-scale entrepreneurs, took hold and coexisted with the large-scale and largely foreign-owned structure that had evolved in the mid-1960s. Westerners learned to play roles in this new system: members of small and midsized import/export firms from the West soon learned the advantages offered by the new system. One rather basic advantage was the lack of any need by the Westerners to build on-site factories and invest in the machinery needed to manufacture their products. Instead these Western businessmen would help establish or work with an often complex network of suppliers who would in turn be linked to even smaller-scale manufacturers further down the chain. One result of this could be seen by the early 1970s in the appearance of the home factories that many members of the lower middle class and the working class either ran or labored in.15

Perhaps the best example of this facet of the “Taiwan miracle,” the term most used for the process of economic transformation, can be found in the development of the shoe industry, an industry whose heyday paralleled Chiang Ching-kuo’s years in power. Ian Skoggard, an anthropologist, has examined this industry, which he sees as a paradigm of Taiwan’s market-dependent (or market-driven) economy. Under this system Taiwanese-owned factories manufacture shoes (or other commodities), which are then sold under the brand name of a transnational or foreign retailing company. The advantage of this arrangement is that Taiwan’s capital-short entrepreneurs, who are removed from affluent foreign markets, are able to industrialize relatively cheaply. However, this same system places upon the Taiwanese businessman the burden of fixed capital costs without the market share to protect that investment. There were other problems as well, for the Taiwanese economy was vulnerable to world recessions, oil embargoes, trade restrictions, changes in exchange rates, and competition from industrializing nations with lower costs of living and even cheaper labor. To deal with these problems, these entrepreneurs spread the risk of investment broadly and this, in turn, resulted in a landscape of small-scale, decentralized industries. In the end, because they had no leverage to influence the prices of either the raw materials or the finished shoes, and had to be content to exist either as price-takers between the large Taiwanese petrochemical manufacturers who supplied the plastics that were their basic raw materials and the foreign marketing companies, they could only realize a profit and maintain their viability through two measures—the hiring of women and the paying of piece wages.16 Skoggard argues that, in the final analysis, even in this industry where the raw materials or semiprocessed materials are available from local sources, it is still labor—and low-cost labor—that fueled the shoe industry and this important segment of the manufacturing sector.17

If we examine Taiwan’s manufactured exports for the 1980s, we can see that most of them were produced either by the large export processors or by the smaller-scale local entrepreneurs who were part of the multilevel export-oriented manufacturing system. During this period, manufactured exports grew 267 percent in value. The effect that this development had could readily be seen. While the population grew at 2 percent per year, the labor force increased 3.6 percent. This differential was caused by the steady decline in the number of people involved in agriculture. The agricultural sector continued to release more labor, and industry gained 8.1 percent per year. By 1980 agriculture employed 20 percent of the work force, industry 42 percent, manufacturing 33 percent, and services 38 percent. The export-oriented strategy had changed the demographic profile of the Taiwanese work force and the face of the physical landscape as well.

There are other indicators of the effectiveness of this strategy over this period that Wang considers its heyday. From 1971 to 1976, exports contributed 80 percent of manufacturing growth or 68 percent of total product growth. And the value increase of exports from 1971 to 1980 was 789 percent. This growth was more in terms of quantity of units produced than in actual unit value.

But what of the economy as whole? This growth, as impressive as it was, could not mask certain realities, realities that as early as the mid-1970s were, government planners believed, impediments to future expansion. The most basic reality was the “sheer inadequacy of the infrastructure.” Under the pressures created by two decades of growth severe bottlenecks appeared in transportation facilities and in power supply.18 On the surface, the power system was adequate, for it showed an 88 percent increase in the years from 1966 to 1971. However, this growth, which averaged about 13 percent a year over this span, still lagged behind the rising demand of the industrial sector. Their demand for power increased 20 percent per year, creating a shortfall of 7 percent. A second problem that faced the industrial sector was the growing demand for key inputs. Only in the textiles and petrochemical-based plants were these demands met. In other industries shortages of inputs—raw or semiprocessed materials—remained the norm.

What was called for was a set of coherent and multifaceted governmental policies and actions. Chiang Ching-kuo, now in full command of his nation, and his technocratic subordinates rose to the challenge and developed initiatives that paved the way for further socioeconomic growth in the late 1970s and in the 1980s. The “Ten Major Projects” was the regime’s full-scale assault on the problems plaguing infrastructure. Chiang decided to invest U.S.$8 billion in ten critical large-scale projects.

Some of these projects were designed to improve transportation. The first was the construction of a north–south superhighway. The second was the construction of a new full-scale international airport. The third was development of two new port facilities. The fourth and the fifth involved improvements of the island’s rail system.19

Other projects were intended to cater to the growing demand for electric power. The economic planners had concluded some years before that nuclear power was the solution and had constructed a reactor in northern Taiwan to meet the needs of the Taipei basin. The second major plant was constructed on the site overlooking the Half-Moon bay near the Kenting/Olanpi resorts in the southernmost part of the island. Development of expanded industrial capacity was included in the plan as well. Two new factories were begun. One was a modern integrated steel mill, and the other was a large shipbuilding plant.20

Funds for these projects came from changes in the income tax system. As a result of these changes, savings were channeled into public capital formation. The multiplier effect that was generated by the public investment and these changes in fiscal policy provided the funds for infrastructure development and jump-started an economy hurt by the rapid rise in post-1973 oil prices.21

The “Ten Major Projects” was but a first step, however. Because he anticipated further expansion of the economy, Chiang Ching-kuo wanted to have his nation ready. Thus the government allocated U.S.$23 billion for fourteen additional large-scale projects. By the end of the 1970s the government’s investment in the nation’s transportation system, power grid, and large-scale industrial facilities had risen more than five times. The results of this investment were ultimately very impressive, as these two indicators suggest: The length of the highways had more than doubled, and the supply of electricity produced had tripled. Cheng concluded, “The improvement of the infrastructure laid the foundation for the further economic advances of the 1980s.”22

A second facet of Chiang’s plan for economic improvement concerned the industrial sector. The technocrats that worked with Chiang were aware of the industrial sector’s two major vulnerabilities—its reliance upon foreign supply of oil and foreign technology.

The oil crisis that came in the wake of the 1973 Yom Kippur War forced the planners to confront the fact that Taiwan, as a nation without its own supplies of oil, would be held captive by events thousands of miles away in the Middle East. They urged that the industries develop more efficient modes of production. They also decided to promote and support those industries that were characterized by “low energy consumption, high technological intensity, and high value added.”23 The industries were also defined as “strategic industries.” These included the machine tool industry, the transportation equipment industry, the electronics industry, and finally, the computer/information industry.24

Of these strategic industries, it was the information/computer industry that proved the most significant. Some statistics demonstrate this. Between 1984 and 1988, the export value of Taiwan-manufactured hardware products increased more than five times, from U.S.$1 billion to U.S.$5.15 billion, and by early 1990 Taiwan had emerged as one of the world’s largest exporters of personal computers.25 The annual visitor to Taipei could see this transformation taking place over the course of these years by visits to Haglers Alley, near the Taipei post office, and the Kuang-hua Market, on Pa-te Road, under the Hsin-sheng Nan Road underpass. In the early 1980s one could see shops on Haglers Alley selling Apple clones and pirated software. However, as the decade went on PC clones became the norm and more sophisticated hardware and software became available.

The transformation of the Kuan-hua market also demonstrates the change. In the late 1970s the site was a two-story bazaar where one could buy cheap antiques, old books and magazines, and student paintings. It was a delightful and always busy site that one could enjoy walking through, searching the stalls at one’s leisure. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, it had changed. While the bookshops were still there, hi-fi stores occupied each story, as did antique stores carrying very high-quality merchandise (from China), and stores that specialized in PCs, printers, peripherals, and software took up much of the floor space. This classic, old, enclosed urban market had become a computer supermarket.26

A third major facet of the new economic initiative concerned the promotion of research and development. In 1979 the regime enacted a statute governing the establishment and administration of science-based industrial parks. The first such industrial park set up was designed to house residential and commercial centers, research institutes and institutes of higher learning, and industrial laboratories. The idea was to provide the enterprises operating in the park with easy access to “a large pool of highly trained scientists and technicians as well as technical data and R-and-D facilities.”27

The Hsin-chu Science-Based Industrial Park (SBIP) was developed over the course of the 1980s, and by 1990 had become recognized as one of the most advanced R and D centers in East Asia. One hundred thirteen high-tech firms had located there, with total revenues of NT$60 billion. The major firms were producers of computers and computer peripherals. There are also producers of integrated circuits, manufacturers of telecommunications equipment, automakers, producers of environmental biotechnology equipment and energy-related equipment. Tsinghua University, Taiwan’s most prestigious technical university, is also located in the area. This center of research and high-tech industry located 45 miles down the freeway from Taipei is the ROC’s Silicon Valley and is, in Cheng’s view, “a model for many developing countries.”28

The high-profile projects that President Chiang promoted over the course of the 1980s were followed by less-spectacular but equally important changes in the way the people of Taiwan did business. There were five facets of this process of fiscal/financial liberalization that were introduced as a way of aligning the island’s economy to the changing world and domestic situation.

One change was spurred by the problem of Taiwan’s trade surplus, a problem recognized by both the Nationalist government and nations like the United States that were Taiwan’s largest trading partners. These nations believed that Taiwan’s domestic markets had to be opened. Before the government officials began reviewing the system there were 8,848 items subject to such restrictions. When the review was concluded, the number had been reduced dramatically to 86. Many more commodities were now allowed in the Taiwanese market. Furthermore the duties on imported goods were reduced to 5.7 percent, a figure similar to that found in the major industrialized nations. Over the course of the 1990s, rates were cut further to 3.5 percent.

Government action of this sort was only one step that was taken. The regime went even further. It voluntarily assisted U.S. firms, helping them secure a larger share of the domestic market as a means of stimulating the sale of foreign exports in Taiwan. And the government conducted extensive market promotions on the island. These policies were aimed at shrinking the trade surplus as a means of reducing tensions between Taipei and Washington.29

A second major fiscal/economic reform involved exchange controls. Before 1987 the government had exercised very tight control on the amounts of foreign currency individuals could hold and on the amount of New Taiwan dollars they could exchange. After 1987 and the new policy on Taiwanese interaction with the mainland, the government had drastically loosened such restrictions. Taiwanese citizens were now permitted to make outward remittances of U.S.$5 million per person per year. There is a ceiling on inward remittances in order to “prevent hot money flocking into Taiwan for speculation.” The new currency regulation had the desired effects: There was an increasing outflow of capital—more than U.S.$25 billion from 1988 to 1992.30

A third step involved export markets for Taiwanese goods. Cheng, Wang, and other economists thought that the Republic of China was vulnerable because of its trade relationship with the United States. In the year 1985, for example, 48 percent of Taiwan’s exports went to the United States. The, U.S. government took initiatives to stem the outflow of capital to Taiwan. One step was to force the appreciation of the New Taiwan Dollar, which, over time, “substantially reduced Taiwan’s competitive power in the international market place.”31 The United States also decided to end Taiwan’s most favored nation trade status. These steps forced the government of the ROC to act. It began a program to diversify Taiwan’s export markets. Trade was expanded with Western Europe and with Southeast Asia—and investment in Southeast Asia also became significant. It also tried to promote its goods with sophisticated marketing campaigns.32 This new policy has succeeded: by the 1990s the percentage of Taiwanese exports to the United States dropped below 30 percent while exports to Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and Western Europe sharply increased.33

A fourth and related economic reform was designed to transform the financial system. Economists on the island had long considered the system outdated and inefficient because of the Bank of China’s monopolistic position and because of laws these experts and those working within the system considered obsolete. The regime took dramatic steps to deal with these problems. Government banks were privatized, private banks were established, and foreign banks were allowed to open up offices.34 The result of these reforms was enhanced efficiency, greater cooperation, liberalization of the whole banking structure, and globalization of what had been a national and rather isolated system.35

A final step taken was the opening to the People’s Republic of China. This step had political, economic, social, and cultural consequences. It is examined in more detail in Chapter 16 within the context of Taiwan’s political evolution and its diplomatic initiatives of the 1980s and 1990s.

The multitude of changes examined here helped pave the way for the island’s development in the 1990s, but more was needed. As Wang Chi-hsien has suggested, the very strategy of export-oriented development had to be reconsidered, a view echoed by Philip Liu.36 The government of the ROC had to take a hard look at basic infrastructure needs. An expanded and modernized infrastructure would be needed in order to help stave off or lessen the impact of the doldrums and the downshifts that developing nations sometimes experienced.37

The regime, now led by Lee Teng-hui, a Taiwanese Presbyterian, did not stand still. Recognizing looming crisis in urban development and transportation and a rising tide of middle-class dissatisfaction with the very visible negative side affects of rapid and often unchecked development, it began to take a new series of steps and consider long-range development goals. In 1991 it began yet another major and very costly initiative—the Six-Year National Development Plan. The projects included in this plan were similar to the large-scale governmental projects of the earlier decades and were intended to improve the island’s infrastructure. One major new plan was the Taipei rapid transit system. This system was designed to combine subways with elevated railways in Taipei and surface system that connected Taipei with nearby suburbs such as Tam-sui.38 Another project was a high-speed rail system designed to connect Taipei with Kao-hsiung.39 These plans and related projects were ambitious, but there were problems, such as land acquisition. The Taipei real estate market was booming, and prices for the land needed raised the cost of the project considerably.40 Design flaws in the system as well as problems with the quality of construction also plagued the effort. Some also criticized the government and conservative firms involved in building the system for creating difficulties in the transfer of needed technologies.41 Financing of so grand a scheme was also a problem.42 Yet the work continued throughout the 1990s.

Infrastructure changes were only one piece of the “redevelopment” puzzle. A second important component were changes in the industrial sector itself. Recognizing this, the Executive Yuan in 1993 began an initiative designed to “boost private investment in manufacturing industries.”43 Another equally ambitious initiative began to take shape in the early 1990s. Recognizing that a PRC-held Hong Kong would no longer serve as the communications and financial/corporate hub of East Asia, Taiwanese officials and business leaders began to make the case for Taipei to play that crucial role.44

This discussion of the implementation of the new multilevel plans developed in the early 1990s suggests that the ROC government saw the need for flexibility and for basic shifts in the nature of the economy. It set in motion what is now an ongoing process of “maturation.”

This section offers insight into the nature of the economic changes that have transformed Taiwanese life, but without exploring the human dimensions of this process of economic development. The next section addresses the question of the impact of this far-reaching economic/fiscal development upon Taiwan’s landscape, Taiwan’s society, and life-style and personal interaction of Taiwan’s citizens.

The economic transformation had direct and very visible effects upon the society of Taiwan between 1971 and 1996. Such changes were many and complex.

One set of changes took place in the educational system. This expansion of the basic system helped make possible changes in career path and occupation. The Nationalists built upon the base that the Presbyterian Church and the Japanese had constructed and upon their decades of experience running an educational system in those parts of China that they controlled.45 After the late 1940s the authorities began to reshape the Taiwanese system so that it would conform to the system they had developed, with some success, on the Chinese mainland.46 The authors of a booklet published by the Ministry of Education show us that the number of students and the number of schools increased steadily from 1950 to 1977. In 1950 there were 1,504 schools serving the needs of 1,054,927 students, figures that rose steadily: By 1961 the figures stood at 3,095 schools and 2,540,665 students. In 1968 the government expanded the system by extending the years of mandatory public education from six to nine. By 1971, six years after the implementation of the export-oriented economic plan, and three years after an increase in the number of years of mandatory education, there were 4,115 schools and 4,130,671 students.47 These figures continued to increase over the next six years, and, in 1977, the final year cited in the booklet, there were 4,698 schools with 4,522,037 students.48 The amount of funding for the school system and the increase in levels of funding from 1961 to 1977—the last year statistics were available to the authors—appears in another chart in the booklet, showing that in 1961 the expenditure for education was about NT$2 billion and that it rose steadily after that date until 1974, when it stood at NT$15 billion and then increased at a higher rate for the next three years to the 1977 level of NT$31 billion. By 1977 the percentage of GNP spent on education stood at about 4.5 percent, an increase of two percentage points over the proportion in the base year, 1961.

The basic educational system, as it existed in 1978, consisted of primary schools that the students throughout the island attended for six years. At that point students had the option of attending junior high schools. After 1968 these junior high schools were constructed all over the country. All students were able to attend these schools, even though they were not compulsory. There was also a system of special junior high schools—elite schools in Taipei, for example—that could be entered only by recommendation, using inside influence (kuan-hsi), or by finding housing nearby. The competition to get into such schools was fierce, for attending such schools better prepared the student for the high school exams and for survival in the elite high schools and in the universities.49

Members of both sexes attended these schools though males outnumbered females in the junior high schools during the 1960s. During that decade there were 22 percent more boys than girls in the system. After the 1968, with the expansion of the junior high school system, the gap narrowed and by the mid-1970s that gap stood at 10 percent.50

There was also a high school system in place after 1950. Of those students who had attended junior high school, 75 percent entered either the academic or the vocational high schools. Those who did not go to either entered the expanding job market. To be admitted to the high schools, students had to take competitive examinations, which often defined one’s occupation and career path. The vast majority of these high schools were public, but the Presbyterian high school in Tainan continued to operate, educating students as it had for more than a century. The impact of Taiwan’s industrialization could be seen in the development of the high school system in the 1970s. After 1971 the number of vocational high schools increased, and those schools already built were expanded. By mid-decade the number of students in such schools exceeded the number of those in the academic high schools. The new industries demanded more educated workers, and these schools provided them.51

High school students who wanted to attend college had one hurdle remaining—another comprehensive examination. By the mid-1970s about 30 percent of those who took these exams passed them. For those who did not get a sufficiently high grade to attend college or university on a full-time basis there were a number of options: night classes for part-time students and a system of junior colleges and normal colleges. Thus the real figure for those attending institutions of higher learning stood at 60 percent.

About half the students who passed the exam were admitted to one of the public universities that dotted the urban and suburban landscapes of the island. The usual procedure was to apply for entrance to a university and a department and then hope that one scored well enough to attend the school of one’s choice. National Taiwan University (T’ai-ta) was first on the list of many students. Following Tai-ta were other institutions in Taipei or its nearby suburbs such as Taiwan Political Affairs University (Cheng-ta), Taiwan Normal University (Shih-ta), or other national universities located in major centers or in smaller cities in other parts of the island. These schools included National Central University (Chung-ta) at Chung-li on the west coast, Tsinghua University in the industrial city of Hsin-chu, Chung Hsing University in Taichung, Cheng-kung University (named after the great hero Cheng Ch’en-kung) in Tainan. The structure of these universities was uniform, with a president at the top and the different colleges within the university headed by various deans, the key figure being the dean of studies. In addition to the deans of the academic divisions—the colleges—there were also deans or administrators for the Office of General Affairs and the Office of the Dean of Discipline and Guidance. Decisions on personnel were made by administrators such as deans and departmental chairpersons and not by members of the faculty.52 This lack of American-style collegiality was seen by some faculty as a major flaw in the system, a system usually depicted by critics as too totalitarian in nature. To that degree, the typical public university reflected the centralized Leninist state of which it was a part.

A system of private universities also developed during this period. By 1978 the number of students at these private universities nearly equaled the number at the public institutions. Students could apply to these when taking the comprehensive exam. Tung-hai University in Taichung was considered the best of these private institutions of higher learning. It was a university begun with help from the Christian Board of Higher Education in Asia and academics with Western church connections had served as faculty and administration during its early years. A second major private and church-related university is Fujen Catholic University. This is run by a number of Catholic orders from Europe and the United States and is a descendent of (or replacement for) the famous Fukien University that had existed on the mainland. This university, like Tung-hai, has graduate programs in various fields. A third major private university is Tam-kang University. This is a privately owned facility with a large campus in Tam-sui, a suburb of Taipei, and a smaller campus in a commercial/residential district in central Taipei.53

Although most universities provided graduate training, many college graduates wished to continue their studies at Japanese, European, or American centers of higher learning.54 The Foundation for Scholarly Exchange, the Chinese-run agency that worked with the Fulbright Foundation, administered the Test of English as a Foreign Language and other exams that opened the way for these students and also provided services to help those applying for education in the United States find a program that matched their interests and abilities. The most talented of these students were also able to apply for Fulbright scholarships to study in the United States or apply for other similar scholarships. Lu Hsiu-lien was one such student who was given a scholarship donated by a Taiwanese entrepreneur that allowed her to go to the University of Illinois at Champagne/Urbana for a master of law degree.55 This same agency served Western scholars doing research at centers on Taiwan or who were involved in scholarly exchange and were teaching in universities on the island.56

Many of the students who went abroad did not return, preferring to spend their lives teaching or working in the West. Their presence has greatly benefited the many educational institutions or private companies where they found a home. However, their home island did suffer and the problem of brain drain was one that government leaders such as K.T. Li were well aware of.57

Taiwan developed an educational system that met the needs of the first generation of those who lived through the economic miracle. The second generation was less well served by the system. By the 1990s, many educators and lay people, though recognizing that national system of education had served their nation well, began to argue that it needed to be changed.

The major area of concern was the system of entrance examinations to the high schools. William Lew and recent critics such as Huang Wu-hsiung found such exams problematic for several reasons. First, they were only objective (i.e., short answer) and not creative. Second, they were the sole yardstick for admission to the two higher levels of schools. Third, they were given only once a year, forcing students who failed to wait a full year before trying again.58

These critics also argued that teachers all too often arranged their material in such a way as to help students prepare for the examinations. Teaching itself was directed not to developing skills related to critical thinking but, rather, to providing the students with the specific forms of knowledge needed to pass the entrance exams. This methodology had, in turn, helped to create an educational system that was too formal and rigid and that stressed memorization and conformity. Critics argued that this discouraged both creative and critical thinking—and suggested, by implication, that the educational system did not met the needs of individuals growing up in a new and more democratic Taiwan.

The seventh Conference on Education in June 1994 demonstrated that the Ministry of Education had listened to the critics and the parents. The conference was attended by 450 individuals, including scholars, educators, educational administrators, members of the non–public education establishment, and students. Attendees came up with many proposals and suggestions, of which the government decided to accept and implement quite a few. Perhaps the most important was the decision to increase the number of high schools, allowing the junior high schools to offer both junior high school and high school courses. Both the academic and vocational curriculum would be introduced at these expanded facilities. Textbook possibilities were also expanded, and those produced privately could now be considered for classroom use. There were also proposals to legalize the alternative schools if such schools met formal standards determined by the ministry.59 The ministry, for its part, agreed to implement these proposals over the course of the next two years.60

There was also criticism of the system of higher education that had developed on Taiwan. During the late 1980s the Ministry of Education began to revise the University Law, which spelled out both administrative and academic policies for the fifty-nine colleges and universities on the island. The draft of the new law then was submitted to the Legislative Yuan. Here it remained, the subject of lively debate and numerous revisions for the next seven years. The revised University Law was finally passed in January 1994.

The new law spelled out basic guidelines for the institutions of higher education, but did not set out specific regulations, as had the previous version of the law. There were guarantees for greater autonomy, and this, in turn, paved the way for a system that had greater freedom and the possibility of greater diversity.61

It was in the area of curriculum that the colleges first felt the impact of the new law and its support of the concept of self-governance. A department within a university or college could now set its own curriculum, pending approval of its own Curriculum Committee and related university or college councils. The ministry still retained the power to set certain general course requirements, but even these are broadly defined. Instead of being required to take certain courses, students could now take one course in each of four different fields. The content of such courses was liberalized as well. A literature course could now contain more modern Chinese novels, for example. The faculty at the universities only began to revise the curriculum after the passage of the act and thus the process of reform moved slowly as 1995 ended.62

Personnel decisions are a second area that has been changed by the new law. Presidents of the universities were chosen by the ministry, and these presidents then had the power to select the other administrators, deans, and departmental chairmen. Now all appointments, including that of the president, are chosen by school committees or, in the case of departmental chairmen, by the faculty of the departments.63 The fourteen major schools can hire faculty independent of ministry influence. However, the other forty-five institutions can hire faculty but need ministry approval to do so.64

A third key area where the new autonomy was felt was in finance. In the mid-1990s the universities began moving toward financial autonomy.65

By the mid-1990s, reforms were being instituted at various levels of the nationwide educational system designed to allow it to change in order to meet the new challenges a developed Republic of China was beginning to face.

The process of economic modernization and the availability of higher levels of education and job training changed the nature of work on Taiwan as well as the career patterns for its citizens for many reasons. First, Taiwan, even after an effective program of land reform had been implemented, was being transformed from a largely rural and agricultural nation to an urbanized and industrialized one.66 Second, the government had put in place an educational system able to train people for the new industrial and technical and professional work environments.67 The new industries demanded better-educated workers and legions of technically trained specialists and managers. The government also needed qualified people to do the type of tasks a regime controlling a mixed economy needed to have done. Finally, an expanding educational system needed qualified teachers and, at the college/university/research institute level, scholars who could produce provocative works of high quality.

Although many people left the countryside, work on farms remained an occupation for some, thanks to a deep and abiding sense of tradition here. Nevertheless, as Huang pointed out, the general commercialization of society destroyed most romanticism about rural life and work. By the early 1990s, only 9.1 percent of the population were still farmers. The majority of these individuals farmed in traditional ways, growing rice and other staples, but others worked in the flower industry and in the other branches of commercial farming. Still others remaining in the rural areas saw that industry provided a means of supporting their farms. Thus, over the course of the 1970s a network of village-based small-scale industry developed.68

But this was not sufficient to sustain life in the countryside, and many more people left agriculture and the small villages in search of greater opportunity for themselves and their families in the towns and cities. There they found access to higher-quality educational facilities as well as greater access to jobs and careers in the industrial and the service sectors to which a better education would give them entrée.

The educational system opened the way for many individuals on the island, providing them with the skills needed to compete in the new occupational marketplace. There was a clear relationship between the highest level of education attained and the career path that one followed, as seen below.

Those with primary and junior high school training moved into the lower rungs of the structure. Some women who could find little else entered the work force as “hairdressers” in the barber shops that were found in these urban centers. The problem is that such shops double as centers of the sex industry, and thus many rather naive country women were drawn into the degrading flesh trade for which the island became famous. Many other women found work in the network of small factories or did piecework in the apartments set up as subas-sembly plants for the handicraft-related industries, the garment industry, or the shoe industry. Men found various forms of low-skilled industrial or service jobs.

After these men and women had saved enough capital, they too became entrepreneurs and ran their own assembly lines or networks of home-based factories. Others set up the noodle stands or snack stands that line the side streets of busy neighborhoods. Families often pooled their resources to set up enclosed restaurants serving a few simple-to-prepare dishes to the breakfast or lunchtime crowd in the alleys and side streets off Roosevelt Road, Hsin-I Road, or Nan-ching East Road.69

With higher levels of education and greater skills at hand, individuals could find employment in the factories that were developing in the industrial parks and the research parks near such cities as Hsin-chu and Taichung. The electronics industry and the computer industry needed individuals with education and vocational training. The government also served as a major employer for people who had graduated high school and had finished their military service. Public transportation was one such service-related area. Skilled workers were also needed in other facets of government services and were important in a society with a growing public infrastructure.70

Those with college and university degrees found even greater opportunity, depending on their specialization. The educational system needed qualified teachers, and teaching offered many a stable and rewarding career, and benefits that the private sector did not offer. Teaching was considered a prestigious occupation, made even more attractive by the various perks. However, until the new wave of 1990s reforms, teaching was often a frustratingly confined profession dominated by a large and authoritarian bureaucracy that could control one’s life even in the classroom.71 The growth of the high-tech industries made engineers and research scientists increasingly valuable, creating demand for graduates of Tsinghua, the engineering and technical university. The development of the research/industrial parks with their focus on research and manufacture of computers and peripherals, and the general development of the computer industry in urban centers, increased the demand for engineers and provided opportunities for professionals who wished to become their own bosses. The small-scale factory suited the vendors of manufacturing components for the expanding computer industry, and such factories and firms often became the homes to the newly trained engineer or the returned student with American or Japanese graduate degrees in hand.

In the 1990s new opportunities developed for those trained in finance and economics. The government was opening up the financial system and allowing foreign banks to enter the Taiwanese marketplace. Those with business-related degrees and with MBAs in hand from Taiwanese or Western institutions found new positions waiting for them. The U.S. training was of particular value, given the island’s close ties to the United States and the size and power of the overseas Taiwanese communities that can now be found in such financial and commercial centers as Los Angeles and New York.

Academia and research institutes served as magnets for others as well. Many of the new American- and Japanese-trained Ph.D.s who returned to Taiwan were able to build careers in the public or private universities. Others found employment at the research institutes of Academia Sinica, which has centers for studies in the humanities, the social sciences, the pure natural sciences, and the applied sciences. The academy also houses libraries and other facilities that are conducive to scholarly pursuits and scholarly production. However, Academia Sinica is not an isolated, ivory tower environment. Many of the scholars had come out of the ranks of the universities or had served at institutes before they went to the West to do their Ph.D. work. And when they returned, many of these scholars taught at the university level even as they did their research in Nan-kang. Academia Sinica and the universities became important as places where many that Hill Gates has termed the “new middle class” would find their homes.

The opening of the educational system and the existence of a wider range of occupational choices for men and women created shifts in traditional patterns of gender definition and relations between the sexes. Between 1971 and 1995 there arose new opportunities for education, new patterns of employment, new perceptions of what constitutes the good life. The rising cost of living transformed the nature of sexual roles and sexual relations in Taiwan in ways that parallel what has taken place in the West.

Traditional concepts of sexual roles and sexual relations remained very much the norm as the 1970s began, though one could see a transitional set of ideas in place that looked ahead to a more modern and Westernized view of both.72 The legislation related to marriage and rights within marriage reflected, in the opinion of feminist social critics writing during the 1970s and 1980s, the traditional patriarchal nature of these concepts of relationships and of rights within relationships. In the eyes of the law and in the attitude of most males, women were second-class citizens. Perceptions and attitudes toward women and their roles in society had changed since the Republican revolution of 1911, and women could now pursue an education from the elementary to the university level. But as the number of women in universities on Taiwan increased, even this hard-won gain was being threatened.

Yet there were social forces working to force changes in men’s attitudes and, ultimately, in the way the citizens and the government of a male-dominated society treated women. One such change was the economic miracle that had forced people to change where they lived and increased both their living standards and their expectation of improvement in that living standard. Both adult members of a nuclear family often found that they had to work to maintain a life-style to which they had grown accustomed. This, in turn, forced changes in the way that people managed their households and assigned and performed household responsibilities.73 These new tensions between husband and wife sometimes led to divorce, an action frowned upon and often avoided in more traditional times.74

Societal factors led to changes in sexual relationships, but ideology and the development of new modes of social consciousness played a part as well. The architect of this movement was Lu Hsiu-lien. In 1971 she wrote an article criticizing a plan for reducing the number of women allowed at the universities. She saw the plan as a direct attack on women by a patriarchal government. Her newspaper article struck a responsive chord, leading to invitations to become a speaker on college campuses and in other forums. She attracted support from among both women and men and began to initiate various programs, in addition to opening a coffeeshop, which served as a meeting ground for women, and a press that published feminist works. For the first five years of her feminist activity, she remained a government employee. However, after an operation to treat a cancerous thyroid and brief summer trip that took her to the West and to Japan, she gave up her position and worked full-time in the movement, setting up hotlines, writing, editing, and publishing new books related to feminism. This activity continued until 1977, when she received an offer to study at Harvard Law School as a visiting scholar. When she returned to Taiwan the next year she entered politics as a member of the tang-wai and thus entered a new stage in what would be a long and multifaceted career.

While Lu was a central figure during the early stage of the movement, other women did important work and some of them took over command of the movement in the late 1970s and in the years of social protest in the early 1980s. In the 1990s the movement continued to grow. Gender studies became a subject studied in the universities and a gender studies program was established at the College of Social Sciences at Tsinghua University in Hsin-chu, a program headed by the American-trained sociologist Chou Pi-erh. Conferences held at the university united feminist academicians and activists, thus broadening the reach of gender studies and maintaining links between theoreticians and scholars and those who engaged in the day-to-day work of defending women’s rights and expanding women’s consciousness.75

Such redefinition of roles and relationships forced the transformation of the traditional Chinese/Taiwanese family system and the creation of family structures better adapted to meet the needs of an industrialized and urbanized society. What had been in the 1890s a largely agrarian society dwelling in small villages or towns had been transformed, first by the Japanese and then by the Nationalists, into a society that was increasingly urban. In that older Taiwanese society, extended families and stem families were the norm. The new industrial, urbanized society had forced individuals to migrate to the cities and the surrounding urban suburbs and in doing so had changed the shape of the family. Now the nuclear family so common in the industrialized West was becoming the norm. Furthermore, as sexual roles changed, older views of male/female responsibilities in the home gave way to the realities of the two-breadwinner families. As the 1970s and 1980s progressed, there came about a gradual sharing of the roles, at least among the middle-class families of urban Taiwan. One might argue that the sharing of tasks had been a part of the social reality of the rural and urban poor, as Hill Gates suggests in her portraits of working-class people. The difference now was a growing sense that shared responsibility also implied sexual equality.76

Some have argued that feminism has not gained much ground in Taiwan and that women remain second-class citizens. However, Taiwanese who are either involved in the movement or observe and study it suggest that feminism on the island has developed along paths more suitable to the society that existed when the movement began and has made substantial gains in various sectors. Such gains are reflected in the role that women now play in the professions and in politics and in the number of self-help groups and support groups that exist as a women’s network on the island.

But the transformation of the extended and stem families had marked social costs. Latch-key kids have increasingly become kids in trouble. A question many asked was, in the words of journalist Amy Lo, “Who’s Supposed to Take Care of the Kids?”77 The need to provide child care forced husbands and wives to redefine their roles within the family. From 1971 to 1995, juvenile delinquency became an increasingly serious problem, in part because of the lack of supervision and the difficulty working parents sometimes had meeting the needs of their children in a fast-paced urban environment. The grandparents, who, in earlier and less complex times, had taken care of the children while their offspring worked, all too often lived in the towns or the villages, to be visited at the lunar new year. Or they lived in other neighborhoods in cities that were more daunting and difficult to get around in. Social critics have also argued that the materialism now increasingly common in Taiwanese life created demands and expectations of its own, which were frustrated by the realities of a family’s income. Television presented images that produced the Taiwanese version of cognitive dissidence—of expectations unfulfilled—and this led in some measure to social problems that the families and the authorities and the social engineers were forced to learn to cope with.78

The transformation of the family has had effects at the other end of the life cycle as well. Families in the dying traditional society would have cared for elderly parents. However, by the 1980s the parents were not usually living in the same home. The burden of care of the elderly now shifted from family to society. Changes in the lives of individuals and families led, in turn, to a transformation of the structure of the social classes and of interclass relationships. Complicating this process of class realignment was the reshaping of ethnic self-definition and the parallel restructuring of interethnic power relationships.

In her seminal essay on ethnicity and class structure in Taiwan, Hill Gates has suggested that by the late 1970s Taiwan society could be broken into five classes.79 The lowest class in the hierarchy is the underclass or lumpen-proletariat, poverty stricken and living on the edge. This class includes aborigines, but the vast majority are from the Taiwanese- and Hakka-speaking majorities and from the second-generation mainlander families. The chronically unemployed and criminals, who are unproductive and parasitical, also belong to this class.

Above this class is the lower or working class, which comprises the great body of industrial workers, landless agricultural workers, sales people, peddlers, and small-town craftsmen. The lives of members of this class have been shaped by low and uncertain incomes, little access to education, no prestige, and very restricted access to political power.

Gates sees two distinct middle classes. The first she terms the “new middle class,” which resembles the class of salarymen in Japan and the bureaucratic “new class” in some state capitalist societies described by Milovan Djilas. The heads of the new-middle-class households are employees of large bureaucratic organizations such as government institutions, schools, and large industrial corporations. Their principal income is in the form of salaries and fringe benefits that include housing, rice allowances, wholesale buying co-ops, and special insurance plans. Education is the key to obtaining such positions. The factors around which the members of the “new middle class” shape their plans for maintaining or improving their social status are education, long-term career commitment to a single institution, and, finally, individual achievement. “For people in this middle class, the maintenance and or improvement of their position depends in part upon the continued power of the institutions that employ them. Consequently, they develop loyalties to and identifications with these institutions. Thus, their perception of their class status—their class consciousness—helps set them apart from the lower class.”80

The second middle class fits the description of the traditional middle class. Members of this second middle class have their own farms, retail or wholesale businesses, and small factories. A major segment of Taiwan’s production comes from such small-scale enterprises, linked in complex webs to wholesalers and to markets on the island or beyond Taiwan. The vast majority of such nonfarm enterprises employ one to six individuals. Members of these firms make up the lower rungs of this second middle class. While their incomes may parallel those of individuals in the working class, their aspirations and self-perceptions are those of the class members above them who have been able to accumulate capital and expand their small-scale enterprises. Businesses with more than six employees—from seven to ninety-nine—are defined as middle-level enterprises. Such firms made up 13 percent of the Taiwanese businesses in 1974 and were capable of “sustaining a secure traditional middle class position for their owners’ families.”81

The key to success in the “traditional middle class” differs markedly from that for the “new middle class”: It depends on the ability to take a small-scale enterprise and turn it into a medium- or mid-level enterprise or one that is even larger. The factors that make for upward mobility in this class are business experience, frugality, long hours of hard work, good contacts, and a reputation for reliability. Education and specialized skills of the type that are demanded in the new middle class are not important here. In fact, education is often seen as needlessly time-consuming, removing one family member from too small a pool of labor.82

It is in defining the nature of the two middle classes and the differences between them and in defining the road to elite or upper-class status that the question of ethnicity and its effects on Taiwanese life can be seen in clearest relief. As shown by many authors, ethnicity and multileveled ethnic conflict have been and continue to be ever-present realities in Taiwanese life. Gates argues, “The paths that lead through the traditional middle classes to the commercial elite and through the new middle class to the bureaucratic elite are quite distinct.” Individuals Gates interviewed talked in terms of two roads. Commerce is seen by some (one may assume, of wai-sheng jen background) as a crooked road that is less valuable to society than the straight road—public service. The general feeling is that being Taiwanese helps one attain traditional middle-class status and more and that “being Taiwanese” implies that one has roots in family and in community and that this provides a solid reputation in business. Ties to local temples and participation in local rituals add to an individual’s sense of belonging to a larger ethnic community and in turn help that individual in his career. One must demonstrate that one is part of the larger mutually supportive network of the local community before that community will support an individual or family.

To be a mainlander gives one different forms of access that allow one to pursue a career path through the institutions of government. Modern Taiwan has been a society ruled by recently arrived immigrants, immigrants who possessed the “legitimacy” to rule and the military power to back up that claim of legitimacy. The types of local networks that a Taiwanese individual can make use of are not available to a mainlander, nor are there local institutions that can also provide support. Rather, mainlanders had nuclear families. What larger networks a given family once had lay to the west, in the PRC. New networks in the government or in government-related industries were developed, and these provided the access that many needed. Furthermore, the nuclear family worked to the advantage of the upwardly mobile mainlander, for nuclear families were better at providing encouragement and support for that family’s children. Parents were able to help their sons or daughters with their schoolwork in a class environment where education determined the career path and the success of the individual. One must add that the wai-sheng jen preference for the straight road reflects the millenia-old Chinese (read Confucian) bias that government service is the noble path and commerce is the ignoble one.83

One must add that the composition of both classes changed over the years as a result of the Taiwanization of the government, intermarriage, and modernization. In the mid-1990s a paradoxical situation developed in which the lines and fractures that separate the wai-sheng jen (people from outside the province) and the pen-ti jen (local people) are less defined even as the Taiwanese majority try to define themselves in terms of a distinctive regional ethnic culture.84

A few other observations must be made concerning these middle classes. Scholars and observers have seen that, over the course of the past twenty-five years, the new middle class and the traditional middle class have both become engines of social change. Members of each group have begun to express their opinions on the nature of life on Taiwan and on the need for an improvement in the general quality of life. But many—more perhaps from the better-educated “new middle class” than from the business-oriented “traditional middle class”—do more than observe the passing scene or make comments about conditions. These increasingly prosperous and well-trained and articulate individuals have begun to play roles in local and regional organizations that focus on problems and issues that range from cultural preservation to environmental change.85 And some among them have moved in the gray area of the public sphere—that zone between voluntary activity and political action—that scholars have been focusing on in recent years. The nature of this middle-class activism in the public sphere is examined in more detail below.

Above the two middle classes is the upper class. The members of this class through public and private enterprise control the means of large-scale production as well as the legal means under which their own and smaller businesses operate.86 Members of this class have sufficient wealth to obtain the goods and life-styles that they desire. They also have access to the best educational institutions, political power, and prestige. While the upper class was at one point mainly mainlander and Taipei-centered, this too has changed in an increasingly open and more socially, as well as politically, democratic society.

Let us return to the question of race and ethnicity and their impact upon the development of modern Taiwanese life. Taiwan is home to two different races, one of which is Austronesian. The aborigine groups who first inhabited the island are of this racial background. In 1985, the year that Hsieh Shih-chung used for statistics in his important article on the yuan-chu-min (indigenous people), there were 317,936 aborigines (to use the most common English term) divided into ten groups. A second and larger group are Han Chinese, usually categorized by linquistic/ethnic or, perhaps more correctly, subethnic groupings. Two of these distinct ethnic groups are descended from groups that came to Taiwan from areas along the South China coast before 1945. One group, the largest population on the island, consists of descendants of peoples who spoke southern Min dialect from the counties of southern Fukien. They speak what is usually called Taiwanese, a dialect resembling the Hokklo spoken in Ch’uen-chou county, Tun-gan county, An-hsi county, and Hsia-men county. The second of the pre-1945 ethnic groups is the Hakka (or K’o-chia), whose ancestors came from the northern counties of Kuangtung. These two groups taken together comprise the pen-ti jen. The third ethnic group is not, strictly speaking, an ethnic group at all. While usually referred to in the politically loaded parlance of the present day as wai-sheng jen this group is really a combination of various mainlander Han ethnic groups that share only the fact that they came to Taiwan after the retrocession of 1945. What they share is their adherence to Mandarin, or kuoyu (national language), as their common tongue and the fact that many came as part of the army or the KMT beareaucracy and thus came to the island as a ruling immigrant elite. One must also add that this is an “ethnic” elite that, for a variety of political and sociocultural reasons, saw a need to impose its “mainstream” greater tradition upon the Hakka and Hokklo/Taiwanese-speaking peoples who had wrested the island from aborigine control.

To a degree, the issue of ethnic differentiation and the resultant ethnic conflict among the Han groups were products of cultural imperialism. As detailed by Douglas Mendel,87 this process, which one can call Mandarinization, was seen in the direct acts of repression in the late 1940s and can also be seen in the years from 1945 to 1970. During the 1970s and the 1980s, the policy of Mandarinization continued in various facets of Taiwan’s educational/cultural life and in the religious realm as well. One of the major facets of cultural imperialism has been the suppression of the Taiwanese language and the teaching of Mandarin in the schools. The language of instruction was Mandarin, and the use of Taiwanese was suppressed. How far this effort went is described by the linguist Robert L. Cheng.88 Cheng argues that the regime made no attempt to create a bilingual system of education but forced the island to accept one that used Mandarin only. He made a strong case for bilingualism, but no one was willing to listen in the heated political atmosphere the 1970s when the article was written. There were other forms of bias against Taiwanese culture and society as well. Taiwan’s own history was barely mentioned in elementary and secondary textbooks: The China that lay across the Taiwan strait was what students learned about. And there was little concern for the preservation of major historical sites as urbanization swallowed up the countryside. The determined efforts of local groups in such cities as Lu-kang, San-hsia, Pan-ch’iao, and Tainan were needed to press authorities to preserve Taiwan’s rich past as an island frontier.89 Furthermore, a few journals dealt with Taiwanese history and culture, and some historians and anthropologists worked on Taiwan-related issues, the study of Taiwan was not a mainstream subject. Only in the 1980s did Taiwan-related issues become central in certain institutes at Academia Sinica and on university campuses. And only in the 1990s was a Taiwan Institute established at Academia Sinica. Since its founding, other universities on the island have held academic conferences, begun formal study of Taiwan and its development, and begun to publish scholarly journals.90 The new Taiwanese consciousness is also reflected in the pages of the Free China Review, published by the Government Information Office. Since 1989, it has gradually included more articles about Taiwanese culture—literature, film, painting, and the performing arts—as well as about Taiwan studies and Taiwan’s history.91 It has also devoted much space to Taiwanese religion and to the culture of the Han and non-Han ethnic groups; one issue was devoted to the Hakka and another to the indigenous peoples.92

Cultural imperialism was also directed against the Presbyterian Church on Taiwan, a major voice for the cause of Taiwanese self-hood. The church leaders made their own public indictment of the regime and its human rights and ethnic policies in a journal called Self-Determination, which was published over the course of the 1970s and 1980s.93

Mandarinization and the suppression of Taiwanese culture is one aspect of the ethnic conflict. These policies and the mainlanders’ systematic exclusion of the Taiwanese from participation in the running of their own country fueled antagonism and distrust. That sense of distrust still runs very deep. However, to address the tensions that existed, Chiang Ching-kuo and other more pragmatic KMT leaders began the process of Mandarinization of the party and the government even as they attempted to suppress the political expressions of Taiwanese identity during the 1970s and 1980s. They were faced with a simple reality—as each year went by the united China that the ROC hoped to reconstruct or recover was becoming an impractical dream. Furthermore, their sons and daughters, the children of the wai-sheng jen, had been born on Taiwan and considered themselves Taiwanese even if the majority did not accept them as such.