5 • The Preclassic Period: Early Civilizations

The advance in the arts and technology that is implied by the word “civilization” is usually bound up with the idea of urbanism. When we think of cities, we think of densely occupied metropolises such as New York City, Paris, ancient Rome, or Beijing, with orderly street plans, often laid out on a grid pattern. Such cities did exist in the Valley of Mexico – Classic Teotihuacan and Aztec Tenochtitlan come immediately to mind. But elsewhere in pre-Spanish Mesoamerica, especially in the lowlands, urbanism took a very different form: there, substantial populations were spread out in a low-density settlement pattern focused upon one or more temple/administrative complexes, with an absence of streets and avenues. This pattern was already present among the Olmecs, as we shall see, and became typical of the later Classic Maya as well as the Zapotecs. Thus, the great Maya cities that were once relegated to the status of near-empty “ceremonial centers” are now considered to have been truly urban.

V. Gordon Childe, among others, held writing to be a critical touchstone of civilized life, but of course it should be remembered that the large and complex Inca empire had no writing at all, relying as it did on the quipu, or knot record, for administrative purposes. However, most of the peoples of Mesoamerica eventually developed systems of writing; the Maya took this trait to its highest degree of development, with a mixed semantic-phonetic script in which they apparently could write anything they wished. As we shall see, Mesoamerican writing has very early origins, appearing in a few areas by the middle or end of the Preclassic period, and in the case of the Olmecs, in the early Preclassic.

“By their works ye shall know them,” and archaeologists tend to judge cultures as civilizations by the presence of great public works and unified, evolved, monumental art styles. Life became organized under the direction of an elite class, usually strengthened by writing and other techniques of bureaucratic administration. Early civilizations were qualitatively different from the village cultures which preceded them, and with which in some cases they co-existed. The kind of art produced by them reveals the sort of compulsive force which held together these first civilized societies, namely, a state religion in which the political leaders were the intermediaries between gods and humans. The monumental sculpture of these ancient peoples therefore tends to be loaded with religious symbolism, calculated to strike awe in the breast of the beholder.

Unless the written record is extraordinarily explicit, which it seldom is in Mesoamerica except for the Classic Maya and the Late Post-Classic peoples of central Mexico, it is extremely difficult to detect the first appearance of the state from archaeological evidence alone. A state is characterized not only by a centralized bureaucratic apparatus in the hands of an elite class, but also by the element of coercion: a standing army and usually a police force. Mesoamerican archaeology provides plentiful data on the emergence of elite, high-status groups, but not very much on warfare or internal control, although both were surely present for over 2,000 years prior to the arrival of the Spaniards. Thus, in the absence of extensive written records, the argument over whether peoples like the Olmec had true states may never be resolved.

As we have said, there was considerable variation in the extent of urbanism among the later cultures of Mesoamerica, from ones in which an elite center was served by low-density populations, often living in villages scattered through the countryside, to ones with vast cities comparable to those of pre-industrial Europe and China. But all of them had administrative hierarchies, and rulers who could call on the peasantry as corvée labor to build and maintain the temples and palaces, and for food to support the non-farming specialists, whether kings, priests, or artisans. In conjunction with an elaborate ritual and civic calendar, writing sprang up early to ensure the proper operation of this process, and to celebrate great events in the life of the elite. Furthermore, in these centers were held at regular intervals the markets in which all sorts of food and manufactures of hinterland and center changed hands. This is the basic Mesoamerican pattern, established in the Preclassic, and persisting until Conquest times in many areas.

The most ancient Mexican civilization is that called “Olmec.” For many years, archaeologists had known about small jade sculptures and other objects in a distinct and powerful style that emphasized human infants with snarling, jaguar-like features. Most of these could be traced to the sweltering Gulf Coast plain, the region of southern Veracruz and neighboring Tabasco, just west of the Maya area. George Vaillant recognized the fundamental unity of all these works, and assigned them to the “Olmeca,” the mysterious “rubber people” described by Sahagún and his Aztec informants as inhabiting jungle country on the Gulf Coast; thus the name became established.

35 Jade effigy ax, known as the “Kunz” ax. The combination of carving, drilling, and incising seen on this piece is characteristic of the Olmec style. Olmec culture. Middle Preclassic period, provenience unknown. Ht 11 in (28 cm).

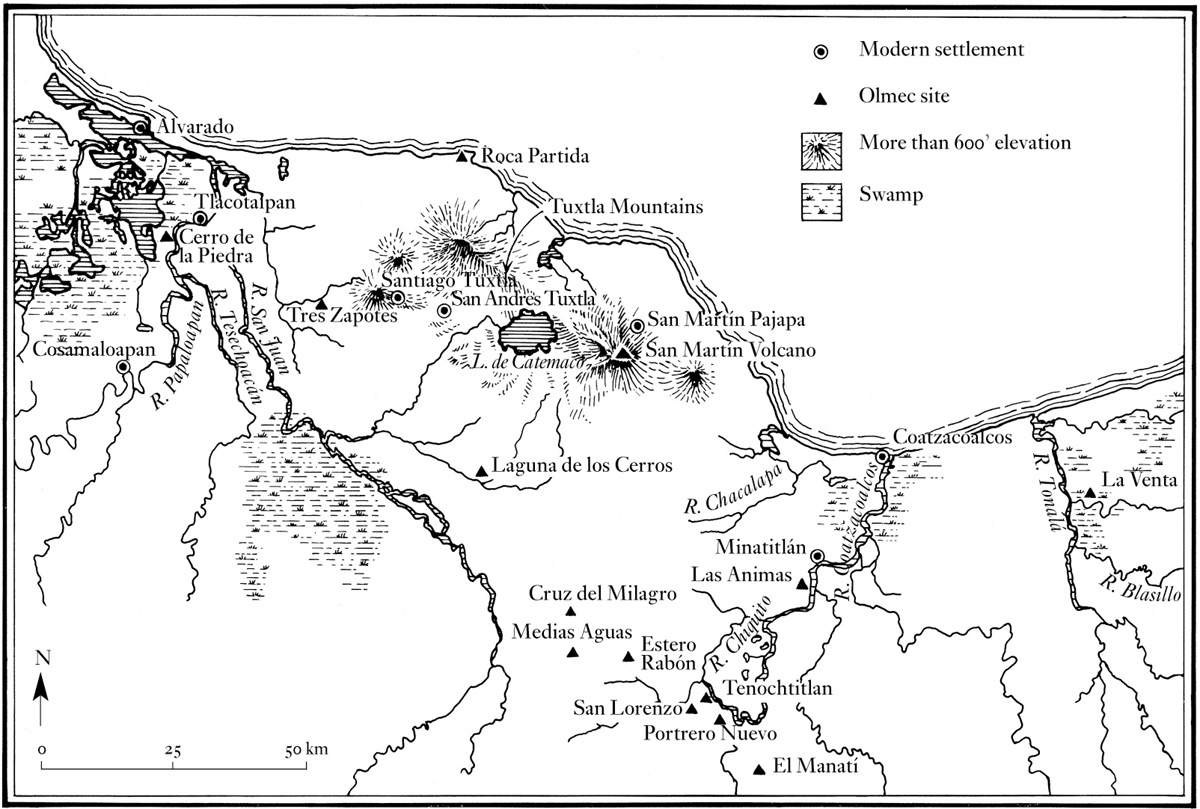

36 Map of the Olmec “heartland.”

Actually, nothing is known of the real people who produced Olmec art, neither the name by which they called themselves nor from where they came. Old poems in Nahuatl, recorded after the Conquest, speak of a legendary land called Tamoanchan, on the eastern sea, settled long before the founding of Teotihuacan

In a certain era

which no one can reckon

which no one can remember,

where there was a government for a long time.1

This tradition is intriguing, for Tamoanchan is not a good Nahuatl name but Mayan, meaning “In the Land of Rain or Mist.” It will be recalled that an isolated Mayan language, Huastec, is still spoken in northern Veracruz. One possibility is that there was an unbroken band of Mayan speech extending along the Gulf Coast all the way from the Maya area proper to the Huasteca, and that the region in which the Olmec civilization was established could have been in those distant times Mayan-speaking. This would suggest that the Olmec homeland was the real Tamoanchan, and that the original “Olmecs” spoke a Mayan tongue.

In contradiction to this hypothesis, some compelling evidence has been advanced by the linguists Lyle Campbell and Terence Kaufman strongly suggesting that the Olmecs spoke an ancestral form of Mixe-Zoquean. There are a large number of Mixe-Zoquean loan words in other Mesoamerican languages, including Mayan. Most of these are words, such as pom (“copal incense”) and kakaw (“chocolate”), associated with high-status activities and ritual typical of early civilization. Although the dominant language of the Olmec area was until recently a form of Nahua, this is generally believed to be a relatively late arrival; on the other hand, Popoloca, a member of the Mixe-Zoquean family, is still spoken along the eastern slopes of the Tuxtla Mountains, in the very region from which the Olmecs obtained the basalt for their monuments. Since the Olmecs were the great, early, culture-bearing force in Mesoamerica, the case for Mixe-Zoquean is very strong.

There has been much controversy about the dating of the Olmec civilization. Its discoverer, Matthew Stirling, consistently held that it predated the Classic Maya civilization, a position which was vehemently opposed by such Mayanists as Sir Eric Thompson. Stirling was backed by the great Mexican scholars Alfonso Caso and Miguel Covarrubias, who held for a placement in the Preclassic period, largely on the grounds that Olmec traits had appeared in sites of that period in the Valley of Mexico and in the state of Morelos. Time has fully borne out Stirling and the Mexican school. A long series of radiocarbon dates from the important Olmec site of La Venta spans the centuries from 1200 to 400 BC, placing the major development of this center entirely within the Middle Preclassic. Another set of dates shows that the site of San Lorenzo is even older, falling within the Early Preclassic (1800–1200 BC), making it contemporary with Tlatilco and other highland sites in which powerful influence from San Lorenzo can be detected. There is now little doubt that all later civilizations in Mesoamerica, whether Mexican or Maya, ultimately rest on an Olmec base.

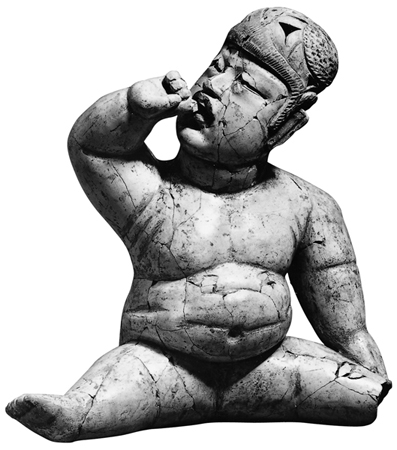

The hallmark of Olmec civilization is the art style. Its most unusual aspect is the iconography on which it is based, through which we glimpse a religion of the strangest sort. The Olmecs may have believed that at some distant time in the past, a woman had cohabited with a jaguar, this union giving rise to a race of were-jaguars, combining the lineaments of felines and men. These monsters are usually shown in Olmec art as somewhat infantile throughout life, with the puffy features of small, fat babies, snarling mouths, toothless gums or long, curved fangs, and even claws. The heads are cleft at the top, perhaps representing some congenital abnormality, but certainly symbolizing the place where corn emerges. Were-jaguars are always quite sexless, with the obesity of eunuchs. In one way or another, the concept of the were-jaguar is at the heart of the Olmec civilization. What were these creatures in function?

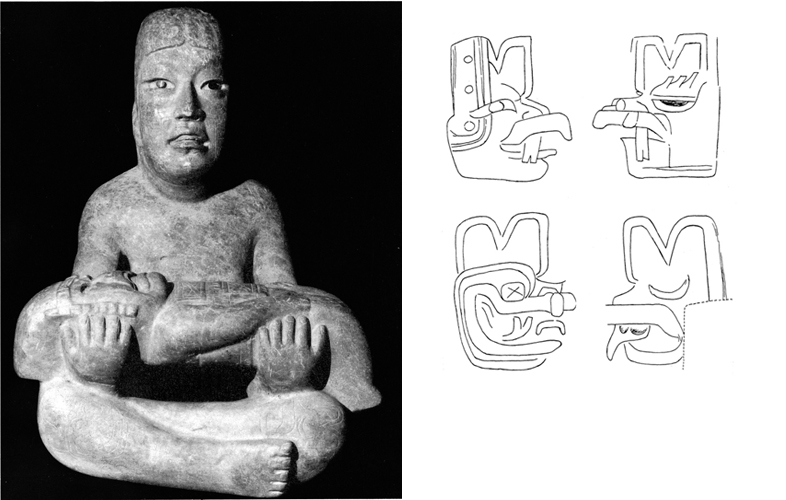

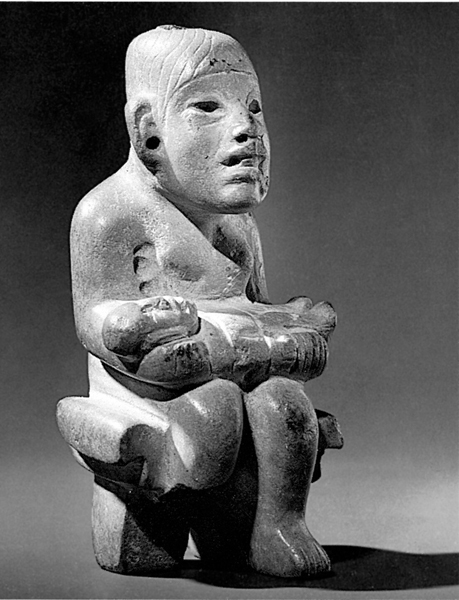

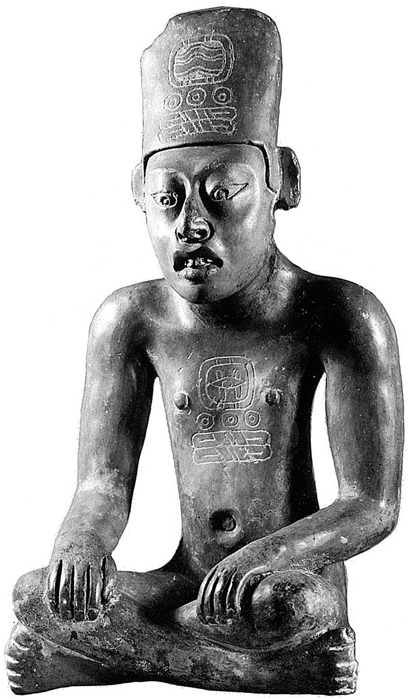

Covarrubias, an artist-archaeologist with a profound feeling for Mesoamerican art styles, developed an ingenious scheme purporting to show that all the various rain gods of the Classic and Post-Classic cultures could be derived from an Olmec were-jaguar prototype. However, the chance find of a large greenstone figure near the village of Las Limas, Veracruz, shows that Olmec iconography was far more complex. This figure represents an adolescent boy or young man, holding in his arms a were-jaguar baby, a theme also to be seen on some Olmec “altars.” Incised on both shoulders and both knees are the profile heads of four Olmec gods; each of them has distinctive iconographic features, although all four -have cleft heads.

37, 38 Greenstone figure from Las Limas, Veracruz (left). A young man or adolescent boy holds the figure of an infant were-jaguar deity in his arms, while his shoulders and knees are incised with the heads of four other deities (see drawings, right). Olmec culture, Middle Preclassic period. Ht 21 ½ in (55 cm).

Following the lead of the Las Limas figure, David Joralemon has been able to show that the Olmecs worshipped a variety of deities, only a few of whom exhibit the features of the jaguar. Just as prominent in their pantheon were such awesome lowland creatures as the cayman and harpy eagle, and fearsome sea creatures like the shark. These were combined in a multitude of forms that bewilder the modern beholder. Thanks to iconographic studies carried out by Karl Taube, the were-jaguar infant held by the Las Limas youth has now been identified as the Maize God, the most important and ubiquitous Olmec deity. Taube has also demonstrated that Covarrubias’s Rain God hypothesis was essentially correct, with the caveat that this was only one in a large Olmec family of supernaturals.

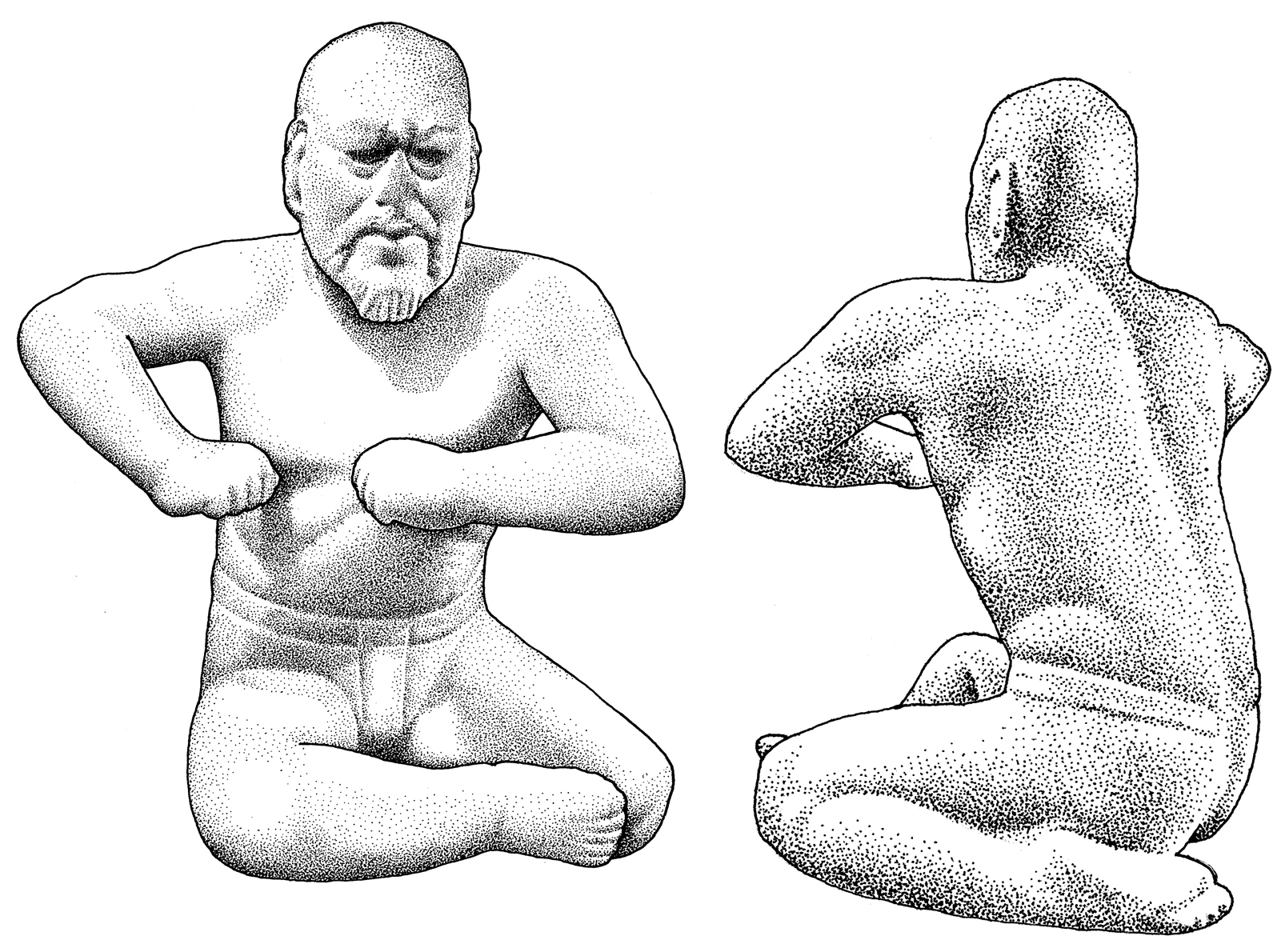

Given its odd content, Olmec art is nevertheless “realistic” and shows a great mastery of form. On the great basalt monuments of the Olmec heartland and in other sculptures, scenes which include what are apparently portraits of real persons are present; many of these are bearded, some with aquiline features. Olmec bas-reliefs are notable in the use of empty space in compositions. The combination of tension in space and the slow rhythm of the lines, which are always curved, produces the overwhelmingly monumental character of the style, no matter how small the object.

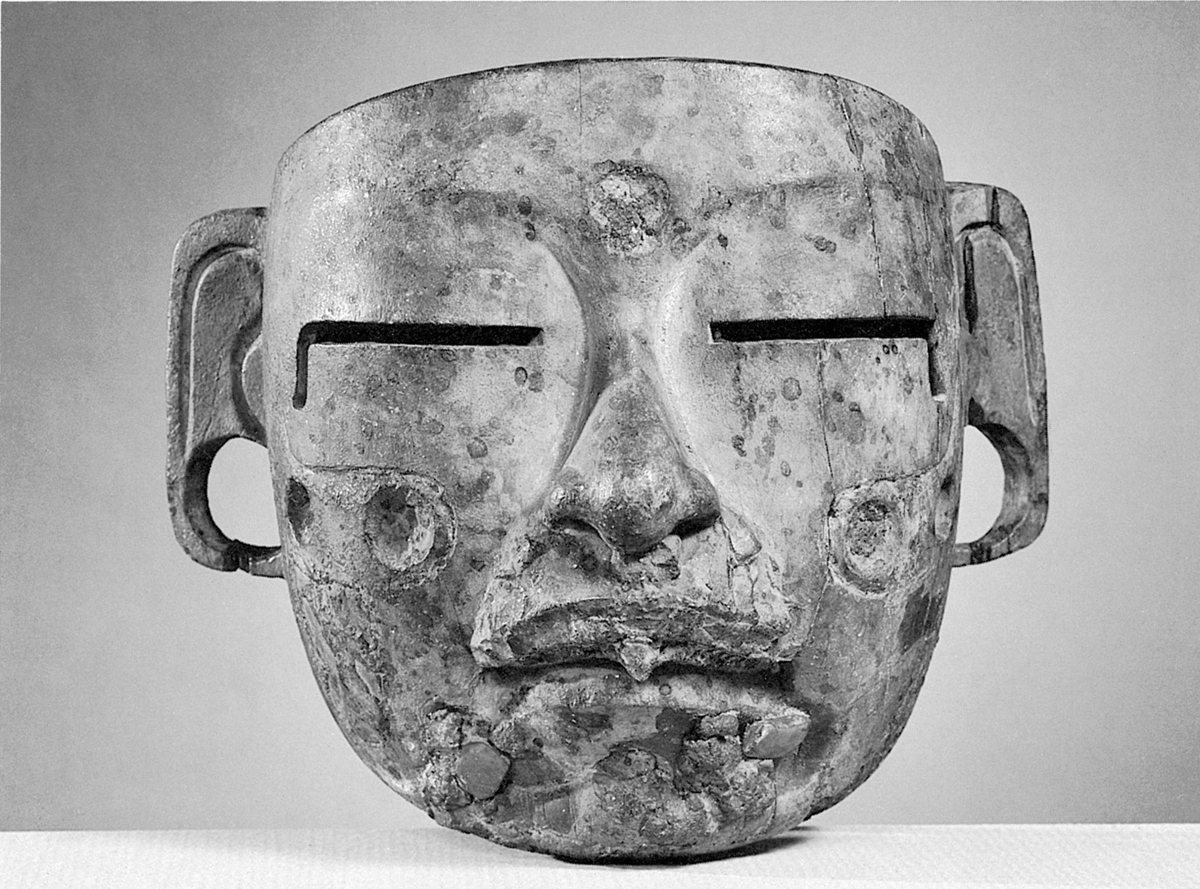

The Olmecs were above all carvers of stone, from the really gigantic Colossal Heads, stelae, and altars of the Veracruz-Tabasco region, to finely carved jade celts, figurines, and pendants. Typical is a combination of carving, drilling (using a reed and wet sand), and delicate incising. Olmec sculptures are usually three-dimensional, to be seen from all sides, not just from the front. Very small sculptures and figurines of a beautiful blue-green jade and of serpentine were, of course, portable, so that we are not always sure of the place of origin of many of these pieces. We now know that the jade was quarried in the Sierra de las Minas in Guatemala, far above the valley of the Motagua River, while the sources of serpentine lay in Oaxaca. Olmec objects of small size have been found all over Mexico, especially in the state of Guerrero in the western part of the Republic, but most of these could have been carried thence by aboriginal trade or even by Olmec missionaries. Among these are magnificent effigy axes of jade, basalt, or other stone, some of which are so thin and completely useless as axes that they must have had a ritual purpose. The gods of rain and maize are on many of these, sometimes inclining towards the feline, sometimes more anthropomorphic, along with other Olmec deities. The Olmec style was also represented in pottery bowls and figurines, and even in wood (in a miraculously preserved mask with jade incrustations from a cave in Guerrero and in the offerings at El Manatí: see below).

39 Basalt figure of a bearded man, the so-called “Wrestler.” Olmec culture, Early or Middle Preclassic period, Antonio Plaza, Veracruz. Ht 26 in (66 cm).

40 Small stone figure of a woman and child, provenience unknown. Olmec culture, Middle Preclassic period. Ht 4 ½ in (11.4 cm).

41 Wooden mask, encrusted with jade, supposedly from a cave near Iguala, Guerrero. Olmec culture, Middle Preclassic period. Ht 7 ½ in (19 cm).

The region of southern Veracruz and neighboring Tabasco has been justifiably called the Olmec “heartland.” Here is where the greatest Olmec sites and the largest number of Olmec monuments are concentrated, and here is where the myth represented in Olmec art appears in its most elaborate form. There is hardly any question that the civilization had its roots and its highest development in that zone, which is little more than 125 miles long by about 50 miles wide (200 × 80 km). The heartland is characterized by a very high annual rainfall (about 120 in or 300 cm) and, before the advent of the white man, by a very high, tropical forest cover, interspersed with savannahs. Much of it is alluvial lowland, formed by the many rivers that meet the Gulf of Mexico nearby. The so-called “dry season” of the heartland is hardly that, for during the winters cold, wet northers sweep down from the north, keeping the soil moist for year-round cultivation. It was in this seemingly inhospitable environment that Mesoamerica’s first civilization was produced.

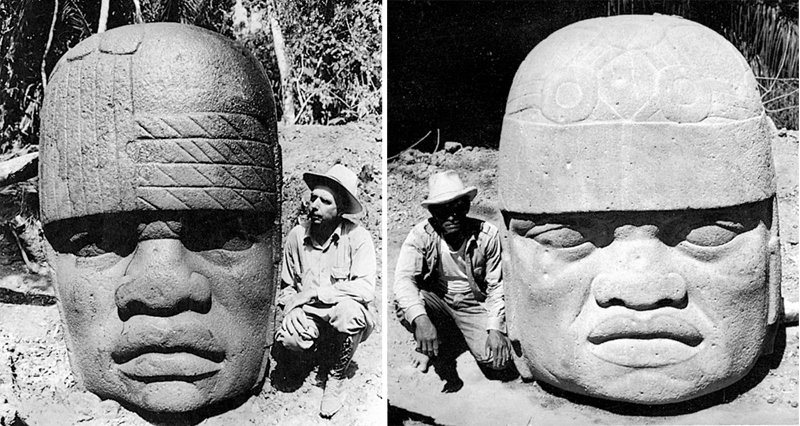

Credit for the discovery of the Olmec civilization goes to Matthew Stirling, who explored and excavated Tres Zapotes, La Venta, and San Lorenzo during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1945, he and his wife Marion were led to the site of San Lorenzo by a report of a stone eye looking up from a trail. They realized that this belonged to one of the Colossal Heads typical of Olmec culture, and excavated the site through two field seasons, during which they discovered a wealth of sculpture, much of it lying in or near the ravines that surround San Lorenzo. However, they were able to date neither the sculpture nor the site itself.

Convinced that San Lorenzo might hold the key to the origin of Olmec civilization, Michael D. Coe directed a Yale archaeological-ecological project there from 1966 to 1968. Since 1991 extensive investigations of San Lorenzo and its hinterland have been undertaken by Ann Cyphers of Mexico’s National University. San Lorenzo is the most important of a cluster of three interconnected sites lying near the flat bottoms of the Coatzacoalcos River, not very far from the center of the heartland. When mapped, it turned out to be a kind of plateau rising about 150 ft (45 m) above the surrounding lowlands; about three-quarters of a mile (1.2 km) long in a north–south direction, excavations proved it to be artificial down to a depth of 23 ft (7 m), with long ridges jutting out on its northwest, west, and south sides. Mirror symmetry is characteristic of San Lorenzo, so that a particular feature on one ridge is mimicked on its counterpart. It is difficult to imagine what the Olmec meant by this gigantic construction of earth, clay, and other materials brought up on the backs of the peasantry, but it is possible that they intended this to be a huge animal effigy, possibly a bird flying east, but never completed because of the destruction of the site.

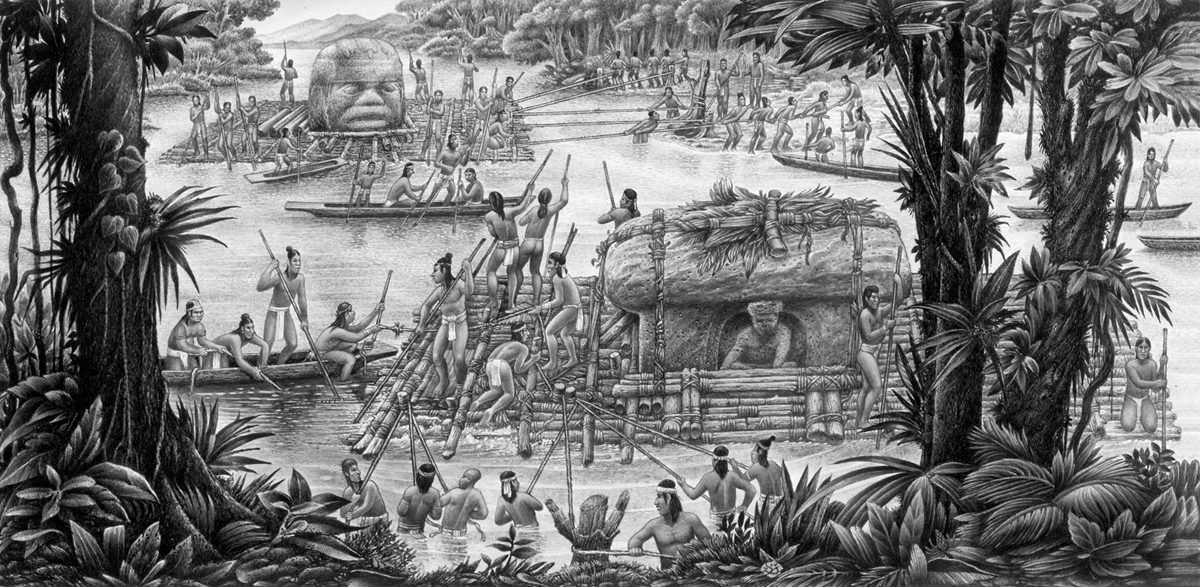

San Lorenzo had first been settled about 1700 BC, perhaps by Mixe-Zoqueans from Soconusco, but by 1500 BC had become thoroughly Olmec. For the next 300 years San Lorenzo was several times larger than any other settlement in Mesoamerica – there was in fact nothing quite like it before or during its apogee. As archaeologists John Clark and Mary Pye have observed, “San Lorenzo had no equals, only peers.” Some of the most magnificent and awe-inspiring sculptures ever discovered in Mexico were fashioned without the benefit of metal tools; petrographic analysis showed them to be basalt which had been quarried from boulders on the volcanic Cerro Cintepec, in the Tuxtla Mountains, a straight-line distance away of 50 miles (80 km). Presumably the stones were dragged down to navigable streams and loaded on great balsa rafts, then floated first down to the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, then up the Coatzacoalcos River, whence they would have had to be dragged, possibly with rollers, up to the San Lorenzo plateau (see ill. 44). The amount of labor that must have been involved staggers the imagination.

The more than 124 Early Preclassic sculptures of San Lorenzo include ten Colossal Heads of great distinction (see ills 42, 43). These are up to 9 ft 4 in (2.85 m) in height and weigh many tons; it is believed that they are all portraits of mighty Olmec rulers, with flat-faced, thick-lipped features. They wear headgear rather like American football helmets that probably served as protection in both war and in the ceremonial game played with a rubber ball throughout Mesomerica. Indeed, we found not only figurines of ball players at San Lorenzo, but also a simple, earthen court constructed for the game. Also typical are the so-called “altars”: large basalt blocks with flat tops that may weigh up to 40 metric tons (see ill. 44). The fronts of these “altars” have niches in which sits the figure of a ruler, either holding a baby Maize God in his arms (probably the theme of royal descent) or holding a rope which binds captives (the theme of the warfare and conquest), depicted in relief on the sides. Rather than actually serving as altars, David Grove has demonstrated that they must have been thrones. One of San Lorenzo’s finest “altars” was found near the satellite site of Potrero Nuevo, and depicts two pot-bellied, atlantean dwarfs supporting the “altar” top with their upraised hands.

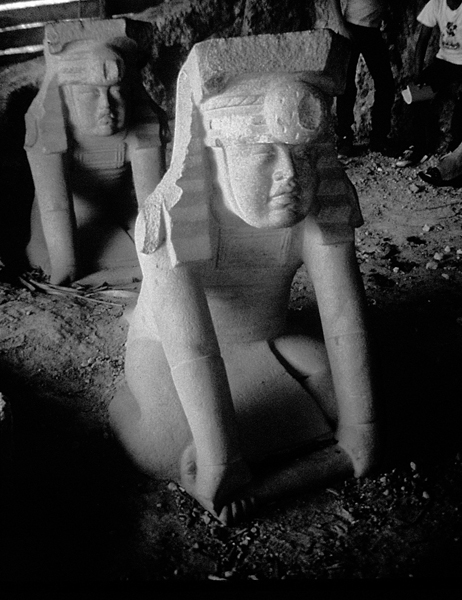

Sculptures could be related in elaborate tableaux, such as the four-piece ensemble uncovered at El Azuzul (see ill. 46). Here two stunningly carved young male figures are shown kneeling before two seated jaguars. While the jaguars are slightly different in size and treatment, the two human figures resemble each other closely. Stories of twins and jaguars abound in the heroic literature of Mesoamerica, suggesting that basic elements of mythology, as well as fundamental rites like the ball game, crystallized earliest at San Lorenzo.

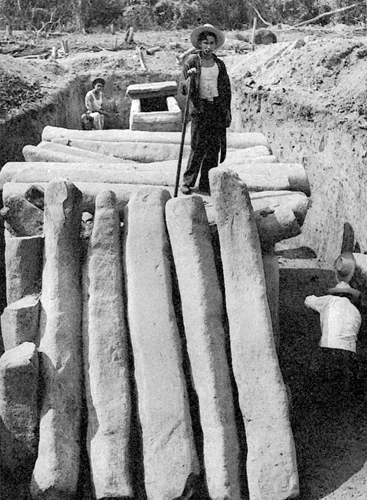

In his work at San Lorenzo, Stirling had encountered trough-shaped basalt stones which he hypothesized were fitted end-to-end to form a kind of aqueduct. In 1967, we actually came across and excavated such a system in situ (see ill. 47). This deeply buried drain line was in the southwestern portion of the site, and consisted of 560 ft (170 m) of laboriously pecked-out stone troughs fitted with basalt covers; three subsidiary lines met it from above at intervals. We have reason to believe that a drain system symmetrical to this exists on the southeastern side of San Lorenzo, and that both served periodically to remove the water from ceremonial pools on the surface of the plateau. Evidence for drains has been found at other Olmec centers, such as La Venta and Laguna de los Cerros, and they must have been a feature of Olmec ritual life.

Large quantities of household debris came from our San Lorenzo phase levels, including pottery bowls and dishes carved with Olmec designs, beautiful Olmec figurines and fragments of white-ware were-jaguar “babies,” and small mirrors, some of them convex, polished from iron-ore nodes, which had perhaps been traded in from distant areas like highland Oaxaca. We recovered thousands of obsidian artifacts, mostly razor-like blades but also dart-points and bone-working tools; there is no natural obsidian in the Gulf Coast heartland, but trace-element analysis showed this material to have been imported from many sources in highland Mexico and Guatemala, testifying to immense trade networks then controlled by the rising Olmec state.

We found no preserved plant remains, but occasional pockets of midden contained mammal, fish, and amphibian remains. The San Lorenzo Olmec were only slightly interested in hunting deer and peccary. The mainstays of their diet were fish such as the snook, and domestic dog. Human bones showing butchering and burn marks were also plentiful, an indication of their cannibalistic propensities. There were also a high number of bones from the marine toad (Bufo marinus), a creature that is inedible because of the poison in its skin, but perhaps utilized for its production of bufotenine, a known hallucinogen.

From our ecological studies, we discovered a great deal about the economic basis of early Olmec civilization along the middle Coatzacoalcos. The bulk of the people were maize farmers, raising two crops a year on the more upland soils where rainy-season inundations do not reach; today, these lands are held communally. In contrast, the Olmec elite must have seized for themselves the rich river levees, where bumper crops are secured after the summer floods have subsided. The rise of the first Mesoamerican state, dominated by a hereditary elite class with judicial, military, and religious power, seems to have been the result of two factors: first, an environment with very high agricultural potential due to year-round rains and wet-season inundations of the river margins, along with abundant fish resources; and second, differential access to the best land by crystallizing social groups. The parallel with ancient Egypt – the “gift of the Nile” – is obvious.

There was nothing egalitarian about San Lorenzo society, as the Colossal Heads testify. While the elite lived in palatial structures at the summit of the site, large numbers of more humble houses were found on the terraced sides of the plateau. The latter were only uncovered when Roberto Lunagómez led a careful survey of the region. One particularly important elite residence on the summit, the “Red Temple,” was fitted with basalt drains and columns, a sign of the highest prestige in this region which lacked stone resources. Attached to the residence were the chief stone sculpture workshops, where the scarce material was turned into public monuments. Ann Cyphers has shown that one of these workshops specialized in recarving stone monuments. Around 1200 BC, this workshop ceased to function, but not before the sculptors or others had deposited the partially finished works in a line near the shop itself. At the same time, the entire site experienced a significant decline in activity and population. Although the specific causes are still unclear, San Lorenzo was never to regain its position as Olmec capital. The shifting rivercourse now bypassed the plateau, possibly causing an upheaval in the distribution systems so important to the San Lorenzo elites. Perhaps there was an uprising from below or outside, although the evidence for this is not as abundant as once thought.

SAN LORENZO and POTRERO NUEVO

42, 43 Monuments 4 (left) and 17 (right), San Lorenzo, Veracruz, shortly after excavation. Monument 17 is one of the smaller Colossal Heads, wearing the typical “football helmet.” The nearest source of the basalt from which this was carved lies more than 50 miles (80 km) to the north. Olmec culture, Early Preclassic period. Hts 5 ft 5¾ in and 5 ft 10 in (1.67 m and 1.78 m) respectively.

44 Artist’s hypothetical reconstruction of transport via balsa rafts of stone monuments from a source in the Tuxtla Mountains to Olmec centers such as San Lorenzo and La Venta.

45 Monument 2, Potrero Nuevo (subsidiary site of San Lorenzo), Veracruz. Two atlantean dwarfs support the top of this basalt “altar,” which probably served as a throne. Olmec culture, Early Preclassic period. Ht 3 ft 1 in (94 cm).

46 Two stone sculptures of young males which face two seated jaguar sculptures in a tableau from El Azuzul. The site functioned as a main entry on to the central plateau of San Lorenzo. Olmec culture, Early Preclassic period.

47 Part of a deeply buried drain line, formed of U-shaped troughs placed end-to-end and fitted with covers. The entire line is made of basalt brought in from the Tuxtla Mountains. Olmec culture, San Lorenzo, Early Preclassic period.

Archaeologists working in the Olmec “heartland” have long lamented the lack of preservation in their sites – the carved wood, the textiles, and almost every other organic material have perished without a trace. There was high excitement, then, when the site of El Manatí, only 10 miles (16 km) southeast of San Lorenzo, came to light. It was discovered in 1988 when locals were digging out a pond for pisciculture, at the foot of the western slope of one of the few hills in the region. The site is thoroughly waterlogged, being bathed by strong springs, with highly complex stratigraphy caused in part by modern disturbances.

The waterlogging has resulted in extraordinary preservation of otherwise perishable Olmec materials, belonging to virtually all phases of San Lorenzo’s development, from 1600 to 1200 BC. An archaeological team directed by Ponciano Ortiz Ceballos of the University of Veracruz has found eighteen wooden figures in situ, all “baby-faced” just like Olmec hollow clay figurines, and each just under 20 in (50 cm) high; all were little more than limbless torsos, and most had been carefully wrapped in mats and tied up, before being placed with heads pointing in the direction of the hill’s summit and covered with a small rock mound. All the wooden busts were discovered in the most recent levels of the site, and one has been radiocarbon-dated to c. 1200 BC. Other objects included polished stone axes, jade and serpentine beads, a wooden staff with a bird’s head on one end and a shark’s tooth (surely a bloodletter) on the other, and an obsidian knife with an asphalt handle. The jade offerings were evident from the earliest levels, thus placing complex Olmec ceremonialism earlier than previously thought. The order and placement of offerings became more complex and prescriptive as time went on, so that earlier rituals that included jade objects thrown into the spring were replaced after 1500 BC with carefully placed bundles of jade axes or other materials, ending finally in the spectacular series of wooden busts. Most surprisingly, the archaeologists turned up seven rubber balls, two of which are from the very earliest activity at the springs; measuring from 3 to 10 in (8 to 25 cm) in diameter, these are the only examples to have survived from pre-Conquest Mesoamerica of what must have been a very common artifact. They confirm that the ball game is at least as old as the Olmec civilization.

48 Wooden busts emerge from the spring at El Manati near San Lorenzo. Jades, rubber balls, and other precious items were also delivered as offerings to the spring. The preservation of wooden sculpture from any period is extremely rare in the tropical lowlands. Olmec culture, Early Preclassic period.

Besides the ball game, one further recreational activity at El Manatí has come to light: chocolate drinking. In a project under the supervision of archaeologist Terry Powis and chemist W. Jeffrey Hurst, residues in the bottom of an Ojochi phase (c. 1600–1500 BC) bowl were found to contain theobromine, the signature alkaloid in chocolate, providing firm proof that the complex process for producing the drink was already known by the Olmecs and their predecessors.

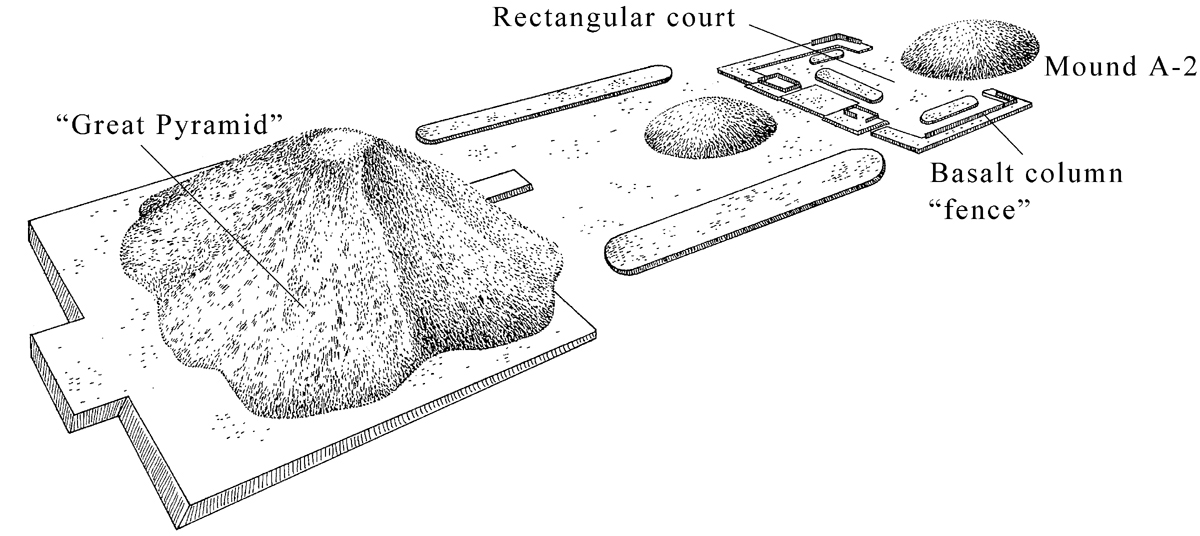

After the downfall of San Lorenzo, its power passed to La Venta, Tabasco, one of the greatest of all Olmec sites, although now largely demolished by oil operations. It is located on an island in a sea-level coastal swamp near the Tonalá River, about 18 miles (29 km) inland from the Gulf. The island has slightly more than 2 sq. miles (5 sq. km) of dry land. The main part of the site itself is in the northern half, and is a linear complex of clay constructions stretched out for 1.2 miles (1.9 km) in a north–south direction; it has been extensively excavated, before its desecration by air strips, bulldozers, and parking lots, first by Matthew Stirling of the Smithsonian Institution and later by the University of California. The major feature at La Venta is a huge pyramid of clay, 110 ft (34 m) high. While the building was once thought to have imitated the form of volcanoes nearby, work on its south side by Rebecca Gonzaléz-Lauck has shown that it was in fact a rectangular pyramid, with stepped sides and inset corners. The idea behind such enormous mounds is of interest here, for this is the largest of its period in Mexico. It is almost as though people were struggling to get closer to the gods, to raise their temples to the sky. This cannot have been their only function, however, for inside many Mesoamerican pyramids have been found elaborate tombs, made during construction of the pyramids themselves, so that it is likely that the temple-pyramid was an outgrowth of the ancient idea of a burial mound or funerary monument. Whether this is so in the case of the La Venta pyramid we do not know, for although still extant it has never been penetrated.

49 Reconstruction of the major ceremonial mound cluster at La Venta. The “pyramid” is now thought to have been rectangular in shape, with stepped sides, rather than imitating the form of nearby volcanoes.

To the north of the Great Pyramid are two long, low mounds on either side of the center-line, and a low mound in the center between these. Then, one comes to a broad, rectangular court or plaza which was once surrounded by a fence of basalt columns, each about 7 ft (over 2 m) tall, set side by side in the top of a low wall made of adobe blocks. Finally, along the center-line, is a large, terraced clay mound. There are some who believe that the layout of the main portion of the site represents a gigantic, abstract jaguar mask.

Robert Heizer calculated that this elite center must have been supported by a hinterland population of at least 18,000 people; the main pyramid alone probably took some 800,000 person-days to construct. Heizer and his colleague Philip Drucker once wrote that the nearest arable land was an area between the Coatzacoalcos and Tonalá Rivers, and that it was on this that the rulers of La Venta depended for food and labor. This land, however, is relatively poor and eroded, making the proposition unlikely. From our own work at San Lorenzo, it would seem far more plausible that the agricultural support area consisted of the rich, natural levees of the tangle of rivers that once flowed in the region of La Venta. This has been borne out by a survey and excavation project directed by William Rust, who has demonstrated that there was a dense occupation of the levee zone beginning at 1750 BC, and other work has shown incipient agriculture in the region may date to as far back as the fifth millennium BC. Concurrently, survey and testing of the La Venta “island” itself makes it clear that this was no empty ceremonial center, but rather a town of some size.

In its heyday, the site must have been vastly impressive, for different colored clays were used for floors, and the sides of platforms were painted in solid colors of red, yellow, and purple. Scattered in the plazas fronting these rainbow-hued structures were a large number of monuments sculptured from basalt. Outstanding among these are the Colossal Heads, of which four were found at La Venta. Large stelae (tall, flat monuments) of the same material were also present. Particularly outstanding is Stela 3, dubbed “Uncle Sam” by archaeologists. On it, two elaborately garbed men face each other, both wearing fantastic headdresses. The figure on the right has a long, aquiline nose and a goatee. Over the two float chubby were-jaguars brandishing war clubs. Also typical are the so-called “altars.” The finest is Altar 5, on which the central figure emerges from the niche holding a jaguar baby in his arms; on the sides, four subsidiary adult figures hold other little were-jaguars, who are squalling and gesticulating in a lively manner. As usual, their heads are cleft, and mouths drawn down in the Olmec snarl.

50 North end of Altar 5 at La Venta. The two adult figures carry baby Maize Gods with cleft heads. Overall height of the monument 3 ft 1 in (94 cm).

A number of buried offerings, perhaps dedicatory, were encountered by the excavators at the site. These usually include quantities of jade or serpentine celts laid carefully in rows; many of these were finely incised with were-jaguar and other figures. A particularly spectacular offering comprised a group of six celts and sixteen standing figurines of serpentine and jade arranged upright in a sort of scene. In some offerings were found finely polished ear flares of jade with attached jade pendants in the outline of jaguar teeth. Certain Olmec sculptures and figurines show persons wearing pectorals of concave shape around the neck, and such have actually come to light in offerings. These turned out to be concave mirrors of magnetite and ilmenite, the reflecting surfaces polished to optical specifications. What were they used for? Experiments have shown that they can not only start fires, but also throw images on flat surfaces like a camera lucida. They were pierced for suspension, and one can imagine the hocus-pocus which some mighty Olmec priest was able to perform with one of these.

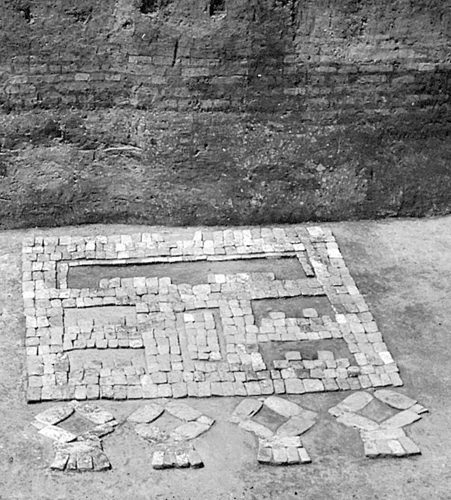

Three rectangular pavements, each c. 15 × 20 ft (4.5 × 6 m), are known at La Venta, each of about 485 blocks of serpentine, laid in the form of a highly abstract jaguar mask. Certain details were left open and emphasized by filling with colored clays. Strange as it may seem, these were offerings, as they were covered up with many feet of clay and adobe layers soon after construction.

In the acid soil of La Venta (as at San Lorenzo), bones disappear quickly, and very few burials have been discovered. Of those found, however, the most outstanding was the tomb in Mound A-2, which was surrounded and roofed with basalt columns. On a floor made of flat limestone slabs were laid the remains of two juveniles, badly rotted when discovered, each wrapped up in a bundle and heavily coated with vermilion paint. With them had been placed an offering of fine jade figurines, beads, a jade pendant in the shape of a clam shell, a sting-ray spine of the same substance, and other objects. Outside the tomb a sandstone “sarcophagus” with a cover had been left, but other than some jade objects on the bottom, nothing was found within but clay fill. It could be that the children or infants in the tomb were monstrosities who to the Olmecs may have resembled were-jaguars and thus merited such treatment.

51 Mosaic pavement of serpentine blocks, representing an abstract jaguar mask, one of three known at La Venta. The pavement was covered over with a layer of mottled pink clay and a platform of adobe bricks.

52 Tomb constructed of basalt pillars at La Venta. The tomb contained several burials accompanied by jade offerings and was covered with an earthen mound.

Like the earlier San Lorenzo, La Venta was deliberately destroyed in ancient times. Its fall was certainly violent, as twenty-four out of forty sculptured monuments were intentionally mutilated. This probably occurred at the end of Middle Preclassic times, around 400–300 BC, for subsequently, following its abandonment as a center, offerings were made with pottery of Late Preclassic cast. As a matter of fact, La Venta may never have lost its significance as a cult center, for among the very latest caches found was a Spanish olive jar of the early Colonial period, and Heizer suspected that offerings may have been made in modern times as well.

Chiapa de Corzo – a La Venta outlier?

Chiapa de Corzo in the Grijalva Depression of Chiapas began as an Early Preclassic village, but by the eighth century BC started to participate in the general orbit of La Venta Olmec civilization. This was marked by the construction of a 20-ft (6-m) high funerary pyramid built of clay and rammed earth. Within this was a major royal tomb, found and excavated in 2010 by Bruce Buchand of the NWAF and Lynneth Lowe of Mexico’s National Autonomous University. Inside a crypt with wooden roof and floor a middle-aged male had been laid to rest, accompanied by two human sacrifices, one of them an infant.

The ruler’s upper teeth had been inlaid in life with small disks of pyrite and mother-of-pearl, a sign of his exalted status. Over the mouth of the corpse had been placed a bivalve shell. He was adorned with a magnificent necklace of over a thousand jade beads identical to those in La Venta burials, interspersed with jade effigy clamshells, and more jade beads and seed pearls adorned his arms and legs. His entire body had been encased in death with a thick layer of bright-red hematite powder. Adjacent to his crypt was that of his royal spouse, equally rich in jade ornaments, and strewn with red powder.

In pits dug into the plaza at the foot of the pyramid were ritual offerings that included La Venta-style pottery, an adult male sacrificial victim, and over 340 stone axes and celts. Along with these was a polished serpentine celt incised with the lineaments of the Olmec Maize God.

In all likelihood this potentate was a satrap of La Venta.

Tres Zapotes and the Long Count calendar

In its day, La Venta was undoubtedly the most powerful and holy place in the Olmec heartland, sacred because of its very inaccessibility; but other great Olmec centers also flourished in the Middle Preclassic. About 100 miles (160 km) northwest of La Venta lies Tres Zapotes, in a setting of low hills above the swampy basin formed by the Papaloapan and San Juan Rivers. It comprises about fifty earthen mounds stretched out along the bank of a stream for 2 miles (3.2 km) with little marked hierarchy among the architectural groups, suggesting to excavator Christopher Pool that the site was controlled by several powerful lineages of equal rank. Pottery and clay figurines recovered from stratigraphic excavations have revealed an early occupation of Tres Zapotes which was apparently contemporaneous with La Venta, but it was during the Late Preclassic that the site reached its zenith. Belonging to this earlier, purely Olmec, horizon are two Colossal Heads like those of La Venta. But the importance of Tres Zapotes lies in its Late Pre-classic stela, discussed below.

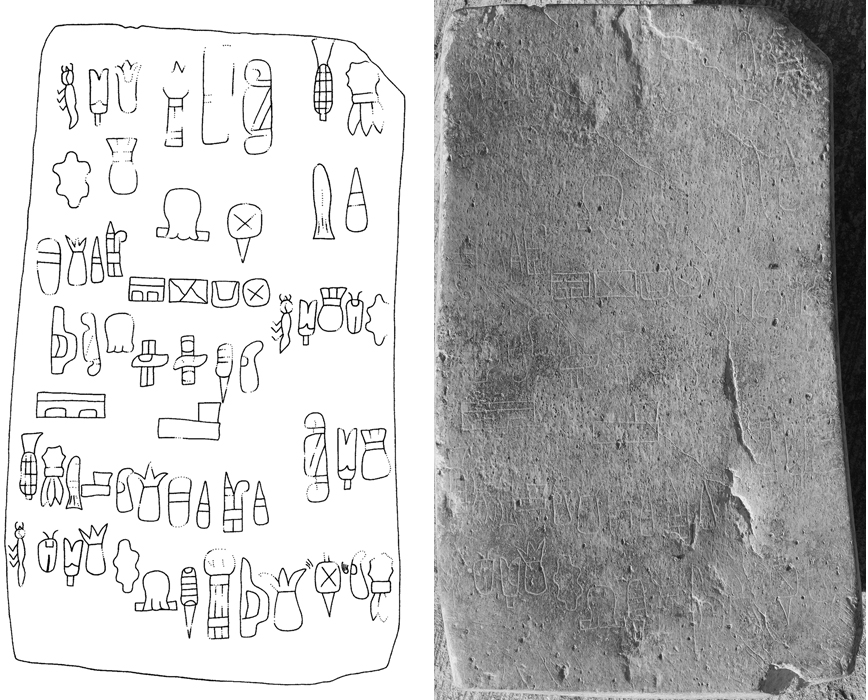

Thus far we have said nothing about writing and the calendar in the Olmec heartland. Actually, no inscriptions or written dates have come to light at La Venta itself. Nonetheless, several fine jade objects in the Olmec style, now in public and private collections but of unknown provenience, are incised with currently unreadable hieroglyphs. More conclusive evidence that the Olmecs had a script appeared in 1999 at a place called El Cascajal, not far north of San Lorenzo: there, archaeologists Ma. Carmen Rodríguez and Ponciano Ortiz found that local villagers had recovered a serpentine block, one face of which was incised with hieroglyphs, from a road cut through an ancient mound. The associated potsherds were almost entirely of the late San Lorenzo phase. The inscription consists of sixty-two signs arranged in more-or-less horizontal lines. Although the signary is derived from Olmec iconography, it bears no resemblance to any later Mesoamerican script and has little likelihood of ever being deciphered.

53 Drawing and close-up detail of Olmec writing incised on a serpentine block from El Cascajal, Veracruz, c. 1000–900 BC. The text is arranged in more-or-less horizontal lines, but cannot yet be read.

It has already been said that Tres Zapotes flourished in the Late Preclassic, after La Venta had been overthrown. Tres Zapotes has produced one of the oldest dated monuments of the New World, Stela C, a fragmentary basalt monument which had been reused in later times. On one side is a very abstract were-jaguar mask in a style which is derivative from Olmec, but not in the true canon. The reverse side bears a date in the Long Count.

The Long Count system of calculating dates needs some explanation. In Chapter 1, it was mentioned that all the Mesoamerican peoples had a calendar that entailed the meshing of the days of a 260-day “Almanac Year” with those of the 365-day solar year. A day in one would not meet a day in the other for 52 years; consequently, any date could be placed within a single 52-year cycle by this means. This is the Calendar Round system, but it obviously is not much help when more than 52 years are involved (just as a Maori would not necessarily know what revolution occurred in ‘76, or a Choctaw what happened to an English king in ‘88), for it would require special knowledge to know in which century the event happened. A more exact way of expressing dates would be a system that counted days elapsed from a definite starting point, such as the founding of Rome or the birth of Christ. This is the role that was fulfilled by the Long Count, confined to the lowland peoples of Mesoamerica and taken to its greatest refinement by the Classic Maya. For reasons unknown to us, the starting date was 13 August 3114 BC (Gregorian), and dates are presented in terms of the numbers of periods of varying length that have elapsed since the mechanism was set in motion. For instance, the largest period was one of 144,000 days, the next of 7,200 days, then 360 days, followed by 20 days and one day. Coefficients were expressed in terms of bar-and-dot numerals, the bars having the value of five and the dots, one. Thus, a bar and two dots stand for “seven.”

In Stela C, the coefficient accompanying the great first period was missing when the stone was discovered by Matthew Stirling, but he reconstructed it as seven. He read the entire date as (7).16.6.16.18, or 3 September 32 BC in terms of our calendar, raising a storm of protests from Mayanists who felt sure that a monument outside Maya territory could not be this old. Stirling was vindicated in 1969 when a Tres Zapotes farmer accidentally turned up the missing top part of the stela, complete with its coefficient of seven. Another date, this time with a fairly long, unread text, is inscribed on a small jade figure in Epi-Olmec style, a duck-billed, winged figure with human features. This is the Tuxtla Statuette (of which more below), discovered many years ago in the Olmec area, with the Long Count date of 8.6.2.4.17 (14 March AD 162). Since both dates fall in the Late Preclassic and were found within the Olmec heartland, it is not unlikely that Olmec literati invented the Long Count and perhaps also developed certain astronomical observations with which the Maya are usually credited.

54 Lower part of Long Count date on Stela C, Tres Zapotes.

55 The Tuxtla Statuette, with Long Count date and other hieroglyphs. Ht 6 in (15 cm).

However, the earliest Long Count date of all turned up on a reused slab at the site of Chiapa de Corzo, in the Grijalva Depression of Chiapas, outside the heartland proper. It bears a date which can be reconstructed as (7.16).3.2.13 or 8 December 36 BC, some four years earlier than Stela C. Quite possibly, we have not yet discovered the answer to where, when, and why the Long Count was invented.

The Olmecs beyond the heartland

Notwithstanding their intellectual and artistic achievements, the Olmecs were by no means a peaceful people. Their monuments show that they fought battles with war clubs, and some individuals carry what seems to be a kind of cestus or knuckle-duster. Whether the indubitable Olmec presence in highland Mexico represents actual invasion from the heartland is still under vigorous debate. The Olmecs of sites like San Lorenzo and La Venta certainly needed substances, often of a prestigious nature, which were unobtainable in their homeland – obsidian, iron-ore for mirrors, serpentine, and (by Middle Preclassic times) jade – and they probably set up trade networks over much of Mexico to get these items. Thus, according to one hypothesis, the frontier Olmec sites could have been trading stations. Kent Flannery has put forth the idea that the Olmec element in places like the Valley of Oaxaca could have been the result of emulation by less advanced peoples who had trade and perhaps even marriage ties with the Olmec elite. And finally, the occurrence of iconography based on the Olmec pantheon over a wide area of Mesoamerica suggests the possibility of missionary efforts on the part of the heartland Olmecs.

Among the sites in central Mexico which have produced Early Preclassic Olmec objects, principally figurines and ceramics, are Tlatilco and Tlapacoya in the Valley of Mexico, and Las Bocas in Puebla; from the latter have come bowls, bottles, and effigy vases, along with fine, white kaolin Olmec babies and human effigies. Many of these items might have been manufactured at San Lorenzo itself.

56 White-ware Olmec baby, said to be from Las Bocas, Puebla. Early Preclassic period, c. 1200-900 BC. Ht 13 ¼ in (34 cm). The function and meaning of such figures are unknown.

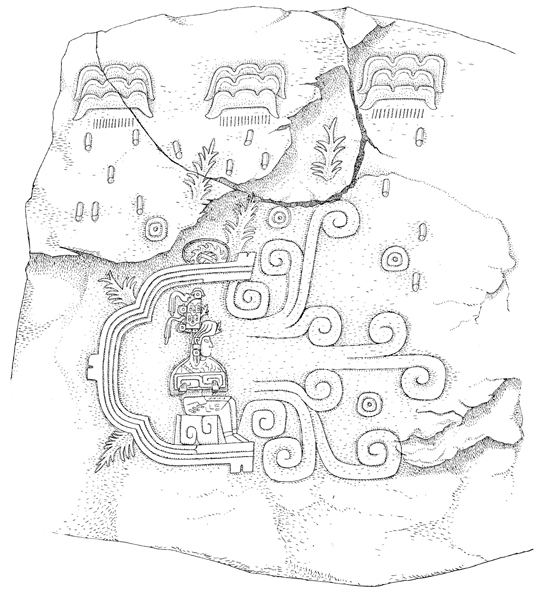

Although it is still in the highlands, the state of Morelos, to the south of the Valley of Mexico, is warm and even subtropical, and might well have proved attractive for the Olmecs. Chalcatzingo is the most important highland Olmec site, and lies in the Amatzinac Valley of eastern Morelos. There, three isolated, igneous intrusions rise over 985 ft (300 m) above the valley floor, and must have been considered sacred in ancient times, as they were by the Aztecs and even the modern villagers. At the juncture of the talus slope and the sheer rock cliff of the central mountain has been found a series of Olmec bas-reliefs carved on boulders. The most elaborate of these bas-reliefs depicts a woman holding a ceremonial bar in her arms, seated upon a throne.

57 Relief 1, Chalcatzingo, Morelos. A woman ruler is seated within a cave or stylized monster mouth which gives off smoke or steam, while raindrops fall from clouds above. Olmec culture, Middle Preclassic period. Ht 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m).

The scene itself takes place within the open, profile mouth of the Olmec earth monster, as though within a cave, which emits smoke or mist. Above this tableau are three stylized rain clouds, from which fall phallic rain drops. The woman must have been a ruler of Chalcatzingo, and the theme is one of power and fertility.

Other sculptures at Chalcatzingo include a relief showing three Olmec warriors brandishing clubs above an ithyphallic captive, and a scene of two rampant felines, each attacking a human. The Feathered Serpent – an important, pan-Mesoamerican deity depicted as a snake adorned with quetzal plumes – makes an appearance on another boulder, with a man disappearing into its open mouth.

In the 1970s, David Grove and Jorge Angulo directed a University of Illinois project at Chalcatzingo which cleared up many of the mysteries posed by the site. The site itself, which consists of platform mounds and terraces below the central mountain, was founded by about 1500 BC, but reached its height during the Middle Preclassic Cantera phase, from 700 to 500 BC, at which time the carvings were apparently made. They are therefore coeval with the apogee of La Venta, which surely was the center from which Olmec influence emanated to Morelos. The Illinois project discovered a table-top “altar” with a relief of the earth monster’s mouth; a child, probably a human sacrifice, had been buried within the “altar.” The Chalcatzingo elite received elaborate crypt burials, one being accompanied by a greenstone figure in the purest La Venta style; jade earspools, pendants, and necklaces were also present.

Although this part of Morelos is somewhat arid, the Cantera-phase farmers did little irrigation, but planted their crops on artificial terraces. Deer and cottontail were hunted, but the most prominent food animal, as in most Preclassic sites, was the dog.

Grove, like Flannery, is skeptical about whether a frontier site like Chalcatzingo actually represents an invasion or takeover by Gulf Coast people, and he too favors the idea of Olmec influence coming in through long-distance trade and marriage alliances. In his view, the monuments, many of which depict the Chalcatzingo rulers, have no local antecedents and may well have been carved by artists imported from the heartland to explain the Olmec belief system to the local people.

Zazacatla, located to the south of Cuernavaca in the municipality of Xochitepec, Morelos, must have been another major Olmec center of the Middle Preclassic. Badly destroyed by modern road building and urban development, it once covered no less than about 1 square mile (about 2.5 sq. km). Rescue operations carried out by INAH archaeologists uncovered several huge platforms built of rammed earth faced with horizontally laid limestone platforms. Four modest-sized stone monuments had been placed in niches, two of which are powerful representations of the Olmec Rain God.

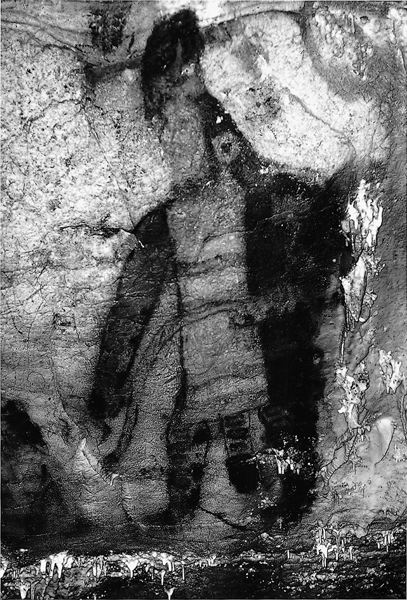

Guerrero is a mountainous, extremely dry state lying south of Morelos, on the way to the Pacific Coast. Many of the most beautiful blue-green Olmec jades have come from this unpromising region, leading Covarrubias to the often-revived but poorly founded claim that this is where the Olmec must have originated. Three extraordinary sites show that the Olmec were here, however. Juxtlahuaca Cave had been known for many years; it lies east of the Guerrero capital, Chilpancingo, near the village of Colotlipa, in one of the most arid parts of the state. The cave, whose importance was first revealed by the Princeton art historian Gillett Griffin and by Carlo Gay, a retired Italian businessman, is a deep cavern. Almost a mile in from the entrance is a series of extraordinary Olmec paintings in polychrome on the cave walls. One of these shows a tall, bearded figure in a red-and-yellow striped tunic, his limbs clad in jaguar pelts and claws; he brandishes a trident-shaped object over a lesser, black-faced figure, probably a captive. Nearby is the undulating form of a red Feathered Serpent, with a panache of green plumes on its head. Deep caves and caverns were traditionally held to be entrances to the Underworld in Mesoamerica, and Juxtlahuaca must have had a connection with secret and chthonic rites celebrated by the frontier Olmec.

58 Polychrome painting on the walls of Juxtlahuaca Cave, Guerrero. A bearded ruler with striped tunic, wearing jaguar arm coverings and jaguar leggings, brandishes a trident-like instrument before a black-faced figure cowering on the lower left. Olmec culture, Early or Middle Preclassic period.

Shortly after the Juxtlahuaca paintings were brought to light, David Grove discovered the cave murals of Oxtotitlan, not very far north of Juxtlahuaca. These paintings are in a shallow rockshelter rather than a cavern, and are dominated by a polychrome representation of an Olmec ruler wearing the mask and feathers of a bird representing an owl, the traditional messenger of the lords of the Underworld. He is seated upon an earth monster throne closely resembling the “altars” of La Venta. It is extremely difficult to date rock art, but it is possible that Juxtlahuaca may be contemporary with San Lorenzo, and Oxtotitlan with La Venta.

The third site was being sacked by looters in the early 1980s before archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History moved in to excavate it properly. Given the name Teopantecuanitlan (“The Place of the Temple of Jaguars”) by the director of the team, Guadalupe Martínez Donjuan, it lies near the confluence of the Amacuzac and Balsas Rivers in the extreme northeast of Guerrero, in a region of dry hills with sparse vegetation. The site consists of three groups of ceremonial constructions spread out over 395 acres (160 hectares). Group A is the most important of these; construction began here with a sunken court of yellow clay, reached by two pairs of stairways on its south side. Each pair of stairs shares a stone tablet decorated with a stylized jaguar face. According to preliminary accounts, this phase has been dated to 1400 BC, leading some Guerrero enthusiasts to revive the Covarrubias hypothesis of Olmec origins.

Phase 2 of Group A at Teopantecuanitlan, dated to 900 BC, sees the substitution of construction in yellow clay by travertine blocks; overlooking the sunken court at this time were four stone monoliths with indubitable Olmec bas-reliefs in straightforward Olmec style. Associated with this phase is the building of a reservoir and canal system, but whether this was for mundane irrigation purposes or more religious and ceremonial – along the lines of the San Lorenzo and La Venta stone drains – is yet unclear.

Sites with Olmec carvings and stelae have been found along the Pacific coastal plain of southeastern Mesoamerica – in Chiapas; the Guatemalan south coast; and as far southeast as Chalchuapa, El Salvador, around 500 miles (800 km) from the Olmec heartland, where a boulder is carved with warlike figures in their characteristic style. So few Olmec sites have been excavated – and even fewer fully published – that it often remains difficult to be very precise about the nature of the Olmec presence beyond the Gulf Coast. Was this Olmec colonization or not? Perhaps some of these sites were founded by small groups of warrior-traders – like the Vikings of the Old World. But decisive evidence for an Olmec colony has been found by David Cheetham at Cantón Corralito, located in the Soconusco plain about 240 miles (400 km) southeast of San Lorenzo. Just about all of its pottery and clay figurines were either a direct import from San Lorenzo or an exact imitation of them.

Some modern revisionists have questioned the reality of an Olmec civilization, and have downgraded the Veracruz-Tabasco “heartland” as the fons et origo of the culture. Basing themselves upon Teopantecuanitlan, there are even those who claim that the Olmec pattern of life began in Guerrero, a position contradicted by the severe environmental constraints posed by that region. Disagreements like this are compounded by the fact that we have no readable written documents for the Olmec, leaving the subject wide open to different interpretations and even unfounded speculation.

Yet whatever we call it, it can hardly be denied that during the Early and Middle Preclassic, there was a powerful, unitary religion that had manifested itself in an all-pervading art style; and that this was the official ideology of the first complex society or societies to be seen in this part of the New World. Its rapid spread has been variously likened to that of Christianity under the Roman Empire, or to that of westernization (or “modernization”) in today’s world. Wherever Olmec influence or the Olmecs themselves went, so did civilized life.

San José Mogote, mentioned in the previous chapter in connection with early Preclassic life, remained the most important regional center in the Valley of Oaxaca until the end of the Middle Preclassic. By that time, it had full-fledged masonry buildings of a public nature; in a corridor connecting two of these, Kent Flannery and Joyce Marcus found a bas-relief threshold stone showing a dead captive with stylized blood flowing from his chest, so placed that anyone entering or leaving the corridor would have to tread on him. Between his legs is a glyphic group possibly representing his name, “1 Eye” in the 260-day ritual calendar. This may be a precursor of the famous Danzantes of Monte Albán, and is one of the oldest examples of writing in Mesoamerica.

59 The Y-shaped Valley of Oaxaca, homeland of the Zapotecs: major sites within the area intensively surveyed by Kent Flannery and his colleagues.

Toward the close of the Middle Preclassic, the Zapotec of the Valley were practicing several forms of irrigation. At Hierve el Agua, in the mountains east of the Valley, there has been found an artificially terraced hillside, irrigated by canals coming from permanent springs charged with calcareous waters that have in effect created a fossilized record from their deposits.

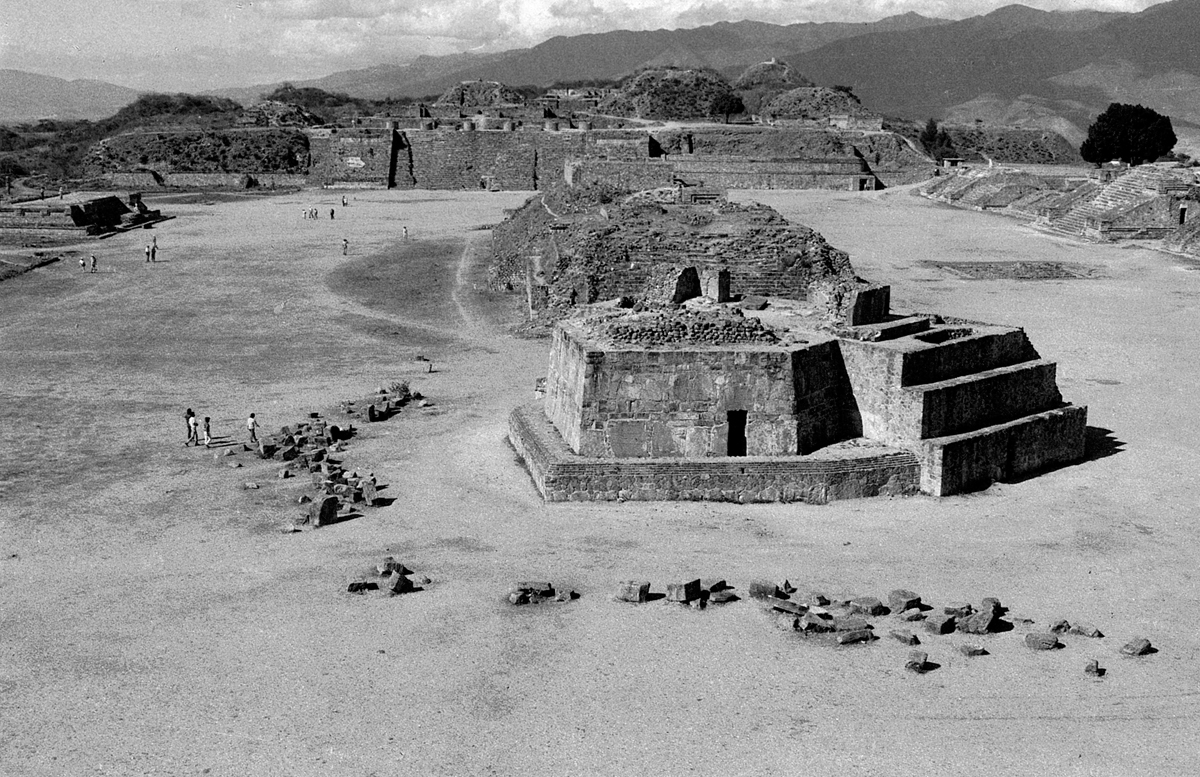

Monte Albán is the greatest of all Zapotec sites, and was constructed on a series of eminences about 1,300 ft (400 m) above the Valley floor, near the close of the Middle Preclassic, about 500–450 BC, when it replaced San José Mogote as the Valley’s most powerful center. The founding of the city took place in a rapid, deliberate episode. The choice to settle here was probably due to the strategic hilltop location at the juncture of the Valley’s three arms. It lies in the heart of the region still occupied by the Zapotec peoples; since there is no evidence for any major population displacement in central Oaxaca until the beginning of the Post-Classic, about AD 900, archaeologists feel reasonably certain that the inhabitants of the site were always speakers of that language.

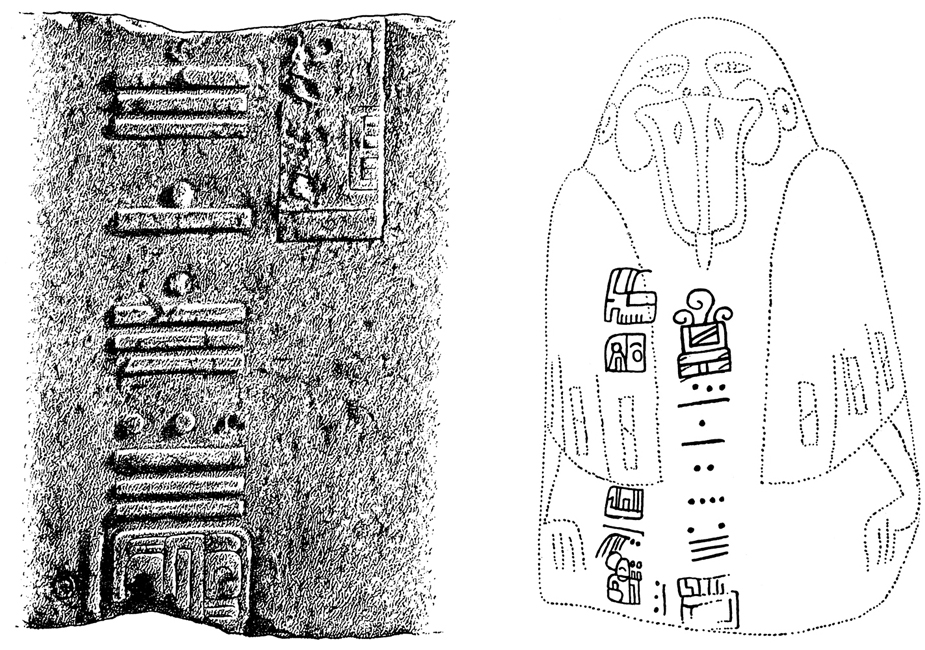

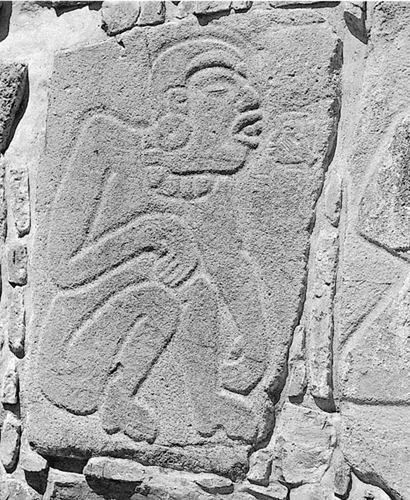

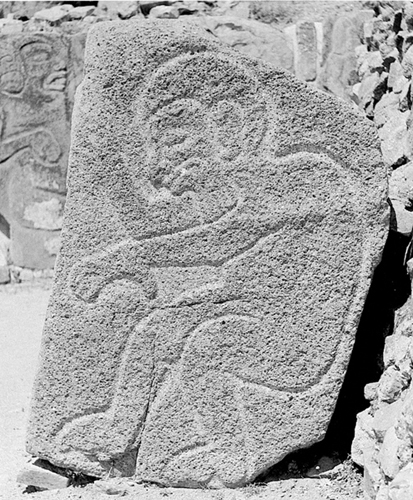

Most of the constructions that meet the eye at Monte Albán are of the Classic period. However, in the southwestern corner of the main plaza, which is laid out on a north–south axis, excavations have disclosed the Temple of the Danzantes, a stone-faced platform contemporary with the first occupation of the site, Monte Albán I. The so-called Danzantes (i.e. “dancers”) are bas-relief figures on large stone slabs set into the outside of the platform. Nude men with slightly Olmecoid features (i.e. the down-turned mouth), the Danzantes are shown in strange, rubbery postures as though they were swimming or dancing in viscous fluid (see ills 60 and 61). Some are represented as old, bearded individuals with toothless gums or with only a single protuberant incisor. About 300 of these strange yet powerful figures are known at Monte Albán, and it might be reasonably asked exactly what their function was, or what they depict. The distorted pose of the limbs, the open mouth, and closed eyes indicate that these are corpses, undoubtedly chiefs or kings slain by the earliest rulers of Monte Albán. In several individuals the genitals are clearly delineated, usually the stigma laid on captives in Mesoamerica where nudity was considered scandalous. Furthermore, there are cases of sexual mutilation depicted on some Danzantes, blood streaming in flowery patterns from the severed part. Evidence to corroborate such violence comes from one Danzante, which is nothing more than a severed head.

Whereas we have scanty evidence for writing and the calendar in the Olmec area, there is abundant testimony of both these in Monte Albán I, whence come our first true literary texts in Mexico. These are carved in low relief on the Danzantes themselves and on other slabs (see ill. 62). Numbers were symbolized by bars and dots, although a finger could substitute for a dot in the numbers 1 and 2. Alfonso Caso has deduced that the glyphs for the days of the 260-day Almanac Year (based on a permutation of 20 named days with 13 numbers) were in use, as well as those for the “months” of the solar year. Thus, these ancient people already had the 52-year cycle, the Calendar Round. However, the Long Count was definitely absent. A fair number of other hieroglyphs, unaccompanied by numerals, also occur, and these probably were symbols in a script which had both phonetic and semantic elements, often combined; some are so placed on the Danzante monuments as to attest to their function as proper names, but none can be read. The ancient Zapotec script will be more fully examined in Chapter 6.

The pottery of Monte Albán I is known from tombs at this site and in others affiliated with it, such as Monte Negro in the Mixteca Alta of western Oaxaca (see ill. 63). It is of a fine gray clay, a characteristic maintained throughout much of the development of Monte Albán. The usual shapes are vases with bridged spouts and bowls with large, hollow tripod supports – typical of the end of the Middle Preclassic and most of the Late Preclassic. Probably the phase does not begin until about 500 BC and ends about 150 BC. Some of the vessels bear modeled and incised figures like the Danzantes, confirming the association.

Monte Albán was surely the capital of a burgeoning state during this Late Preclassic period. The city was able to do several things associated with later Mesoamerican states: to develop a distinctive art style along with a script, both associated with the necessary proclamations of power and sacrality, and to gather a large population around the urban center. Two investigators, Richard Blanton and Stephen Kowalewski, give its population as 10,000 to 20,000, and the first Monte Albán palaces seem to appear at this time to meet the administrative needs of the local and Valley-wide citizenry.

BAS-RELIEFS at MONTE ALBÁN I

60 Bas-relief figure of a so-called Danzante or “dancer.” This is a portrait of a slain enemy, whose name glyph appears in front of his mouth.

61 Bas-relief figure of a bearded Danzante.

62 Hieroglyphic inscription on large stone slab. Monte Albán I, Middle to Late Preclassic period.

63 Fragment of an effigy whistling jar, provenience unknown. The vessel originally consisted of two connected chambers, and when liquid was poured out, air was forced through a whistle in the head. Monte Albán I culture, Middle to Late Preclassic period.

64 Funerary urn from Cuilapan, Oaxaca, probably representing a young god. The incised hieroglyphs may be the days 13 Water and 13 Flint. Monte Albán II culture, Late Preclassic period.

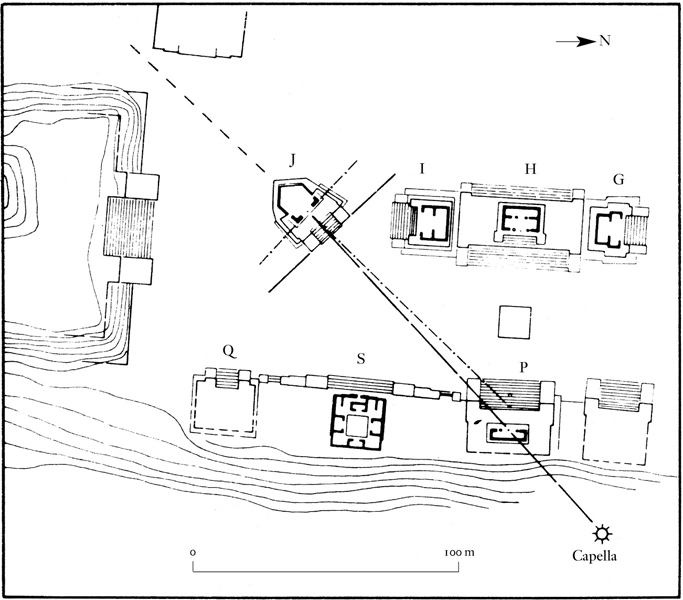

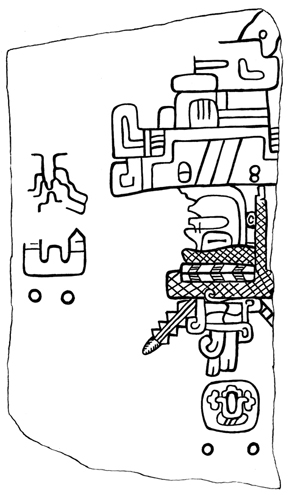

The development from the first phase of the site to Monte Albán II, which is terminal Preclassic and therefore dates from about 150 BC to AD 150, was gradual. Near the southern end of the main plaza of the site was erected Building J, a stone-faced construction in the form of a great arrowhead pointing southwest. The peculiar orientation of this building has been examined by the astronomer Anthony Aveni and the architect Horst Hartung, who have pointed out important alignments with the bright star Capella. The exterior of the building is set with over forty inscribed stone slabs all bearing a very similar text. These Monte Albán II inscriptions generally consist of an upside-down head with closed eyes and elaborate headdress, below a stepped glyph for “mountain” or “town” (see ill. 67); over this is the name of the place, seemingly given phonetically in rebus fashion (like the “I saw Aunt Rose” puzzles of youth). In its most complete form, the text is accompanied by the symbols for year, month, and day. There are also various yet-untranslated glyphs. Such inscriptions were correctly interpreted by Alfonso Caso as records of town conquests, the inverted heads being the defeated kings. It is certain that all are in the Zapotec language.

BUILDING J at MONTE ALBÁN

65, 66 Building J at Monte Albán, a stone-faced structure in the form of a great arrowhead pointing southwest. The astronomer Anthony Aveni has identified an alignment of Building J (see drawing) with the bright star Capella. Monte Albán II culture, Late Preclassic period.

67 Hieroglyphs representing a conquered town, from Building J at Monte Albán.

This obsession with the recording of victories over enemies is one characterizing early civilizations the world over, and the rising Preclassic states of Mexico were no exception. It speaks for a time when state polities were relatively small and engaged in mutual warfare, when no ruler could extend his sway over a territory large enough to be called an empire. These independent elite societies shared a religious and artistic culture that found expression in funerary urns and related burial furniture (see ill. 64).

Dainzú, an important site of Late Preclassic and Classic date lying some 12 ½ miles (20 km) southeast of Oaxaca City, has a large Monte Albán II platform c. 150 ft (45 m) long; the 1966 investigations of Ignacio Bernal showed that its base was faced with fifty stones carved in low relief, somewhat reminiscent of the Danzantes. Most of the figures are ball players wearing elaborate protective gear, including barred helmets like those of the medieval knights, knee guards, and gauntlets, and each figure has a small ball in the hand. It is a measure of our ignorance of the early Mesoamerican mind that we are not sure whether these represent the victors or the vanquished!

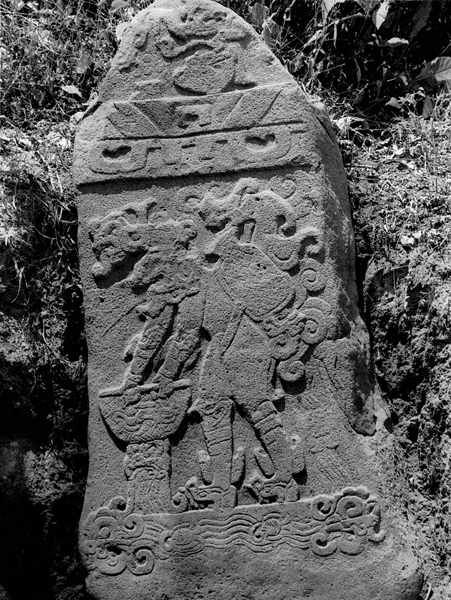

Another culture of the Preclassic period upon which we will touch is of high significance. This is the civilization centered on the site of Izapa, located in the southeastern part of the state of Chiapas on a tributary stream of the Suchiate River, which divides Mexico from Guatemala. We are here in the broad, Pacific Coast plain, one of the most unbearably hot, but at the same time incredibly fertile, regions of Mexico. Izapa is a very large site, with numbers of earthen mounds faced with river cobbles, all forming a maze of courts and plazas in which the stone monuments are located. There is possibly a ball court, formed by two long, earth embankments. Samples of pottery taken from Izapa show it to have been founded in the Early Preclassic, and to have reached its height in the Late Preclassic, persisting into the Proto-Classic period.

The art style as expressed in bas-reliefs is highly distinctive. Although obviously derived from the Olmecs, it differs in its use of large, cluttered, baroque compositions with several figures, as opposed to the Olmec focus on the single figure of the ruler. Several of these multi-figure Izapan compositions are concerned with the sacred stories of Mesoamerican divine heroes; many of these stories were still in use when the Spanish arrived almost 2,000 years later. Izapan style appears on stone stelae that often are associated with “altars” placed in front, the latter crudely carved to represent giant toads, symbols of rain. The principal gods are metamorphoses of the old gods of the Olmecs, the upper lip of the deity now tremendously extended to the degree that it resembles the trunk of a tapir. Most scenes on Izapan stelae take place under a sky band in the form of stylized monster teeth, from which may descend a winged figure on a background of swirling clouds. On Stela 1 (see ill. 68), a “Long-lipped God” – a prototype of the Maya Rain God Chac – is depicted with feet in the form of reptile heads, walking on water from which he dips fish to be placed in a basketry creel on his back, while on Stela 3, a serpent-footed deity brandishes a club. Most interesting of all is Stela 21, on which a warrior holds the head of a decapitated enemy; in the background, an important person is carried in a sedan chair, the roof of which is embellished with a crouching jaguar.

68 Stela 1, Izapa, Chiapas. At the top is a stylized mouth representing the sky. Below, a god with reptile-head feet is dipping fish from the water with a net; he carries a bottle-shaped creel strapped to his back. Izapan style, Late Preclassic period. Ht 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in).

The real importance of the Izapan civilization is that it is the connecting link in time and space between the earlier Olmec civilization and the later Classic Maya. Izapan monuments are found scattered down the Pacific Coast of Guatemala and up into the highlands in the vicinity of Guatemala City. On the other side of the highlands, in the lowland jungle of northern Guatemala, the very earliest Maya monuments appear to be derived from Izapan prototypes. Moreover, not only the stela-and-altar complex, the “Long-lipped Gods,” and the baroque style itself were adopted from the Izapan culture by the Maya, but the priority of Izapa in the very important adoption of the Long Count is quite clear-cut: the most ancient dated Maya monument reads AD 292, while a stela in Izapan style at El Baúl, Guatemala, bears a Long Count date 256 years earlier.

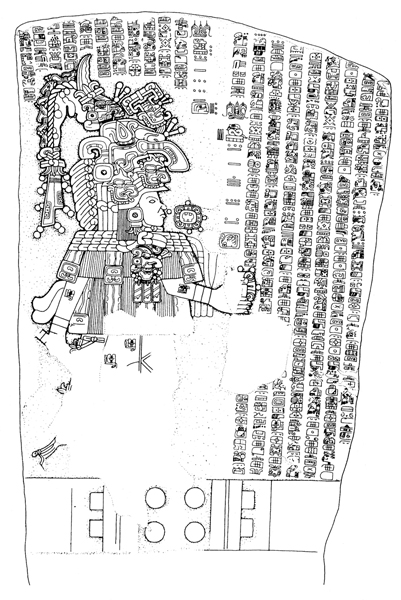

La Mojarra and the Isthmian script

Chance finds can often lead archaeologists in new directions. Such has been the case with the La Mojarra stela, accidentally discovered in November 1986 beneath the waters of the Acula River, in the Veracruz lowlands about half way between Tres Zapotes and the Classic site of Cerro de las Mesas. This 4-ton monument is of fine-grained basalt, and depicts an imposing, standing figure, richly attired in Izapan style, with a towering headdress formed of multiple masks of a bird-monster known for the Maya Late Preclassic, topped by a fish creature which has been identified as a shark.

But it is the accompanying hieroglyphic text which caused a sensation among Mesoamerican epigraphers: arranged in 21 beautifully drawn columns are about 400 signs, the longest inscribed text known thus far for Mesoamerica. The script is clearly the same as that inscribed on the Tuxtla Statuette, but otherwise unknown, and has been dubbed “Isthmian” by specialists. Intensive study by John Justeson and Terence Kaufman has resulted in a proposed decipherment of Isthmian, in which the script is identified as a mixed, partly logographic (semantic), partly phonetic system which reproduces the proto-Zoquean language – which would fit in with the known distribution of the Mixe-Zoquean linguistic family in this area. However, this proposed decipherment has not received general acceptance, a situation that will continue until a larger body of “Isthmian” texts comes to light, or even less likely, a bilingual inscription in Isthmian and Maya.

There are two Long Count dates on the La Mojarra stela: 8.5.3.3.5 and 8.5.16.9.7, corresponding respectively to 21 May AD 143 and 13 July AD 156 (the latter only six years earlier than the Tuxtla Statuette), placing the stela, and the Isthmian script, toward the end of the Late Preclassic. There are obvious connections here with both the Izapan civilization of the Pacific Coast and the Guatemalan highlands, and with the early Maya civilization then taking form in the Petén-Yucatan lowlands, but until further Isthmian texts are found and studied, the script will remain completely undeciphered and its external relationships will continue to be a mystery.

69 Stela 1, La Mojarra, Veracruz. End of Late Preclassic period.