Let the soldier Bernal Díaz, who was with Hernán Cortés when the Spaniards first approached the island capital of Tenochtitlan on 8 November 1511, tell us his impressions of his first glimpse of the Aztec citadel:

During the morning, we arrived at a broad causeway and continued our march towards Iztapalapa, and when we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land and that straight and level Causeway going towards Mexico, we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments they tell of in the legend of Amadis, on account of the great towers and temples and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream.6

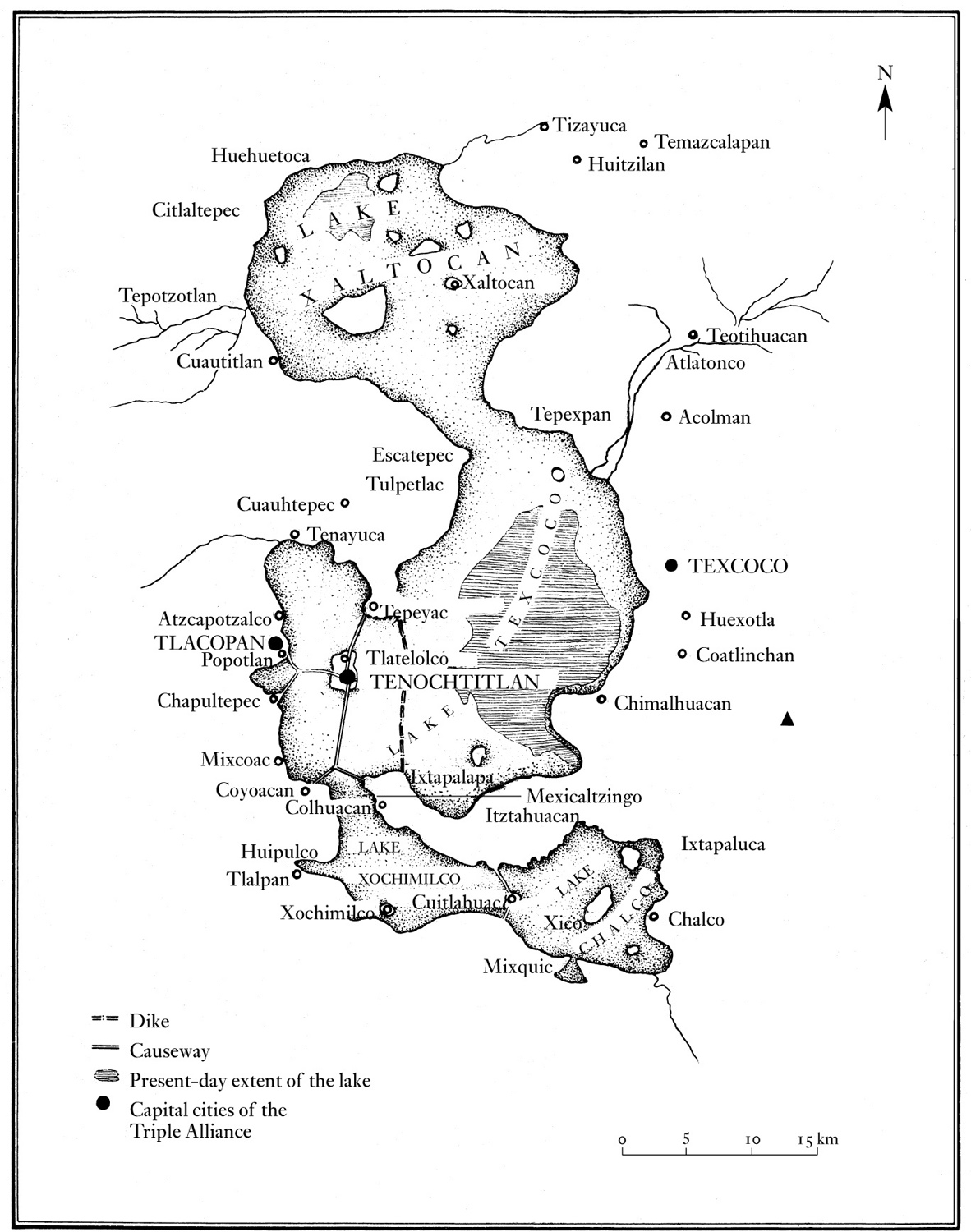

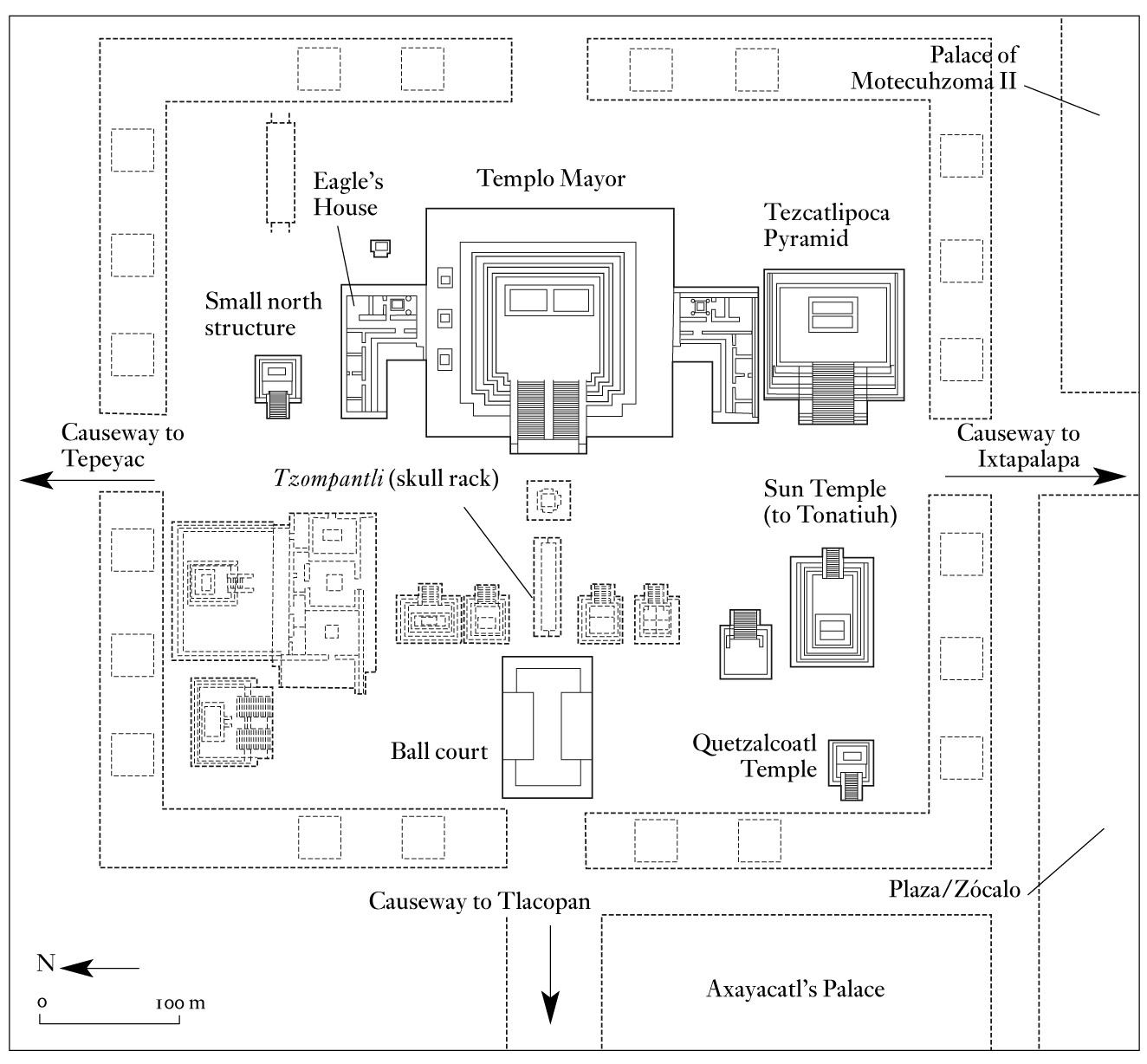

The island was connected to the mainland by three principal causeways, “each as broad as a horseman’s lance,” says Cortés, running north to Tepeyac, west to Tlacopan, and south to Coyoacan (see ill. 145). These were broken at intervals by openings through which canoes could pass, and were spanned by removable bridges, thus also serving a defensive purpose; moreover, access to the city by the enemy was barred by manned gatehouses. Across the western causeway ran a great masonry aqueduct carrying water to Tenochtitlan from the spring at Chapultepec, the flow being “as thick as a man’s body.”

The Spanish conquerors called the Aztec capital another Venice, and they should have known, for many of them had actually been to that place. With a total area of about 5 sq. miles (14 sq. km), the city (meaning by this Tenochtitlan and its satellite Tlatelolco) was laid out on a grid, according to a fragmentary sixteenth-century map of one section. Running north and south were long canals thronged with canoe traffic and each bordered by a lane; larger canals cut these at angles. Between these watery “streets” were arranged in regular fashion rectangular plots of land with their houses. In effect, this was a chinampa city.

A brief description of chinampa cultivation, mentioned in Chapter 1, will not be out of place here. The technique is well known, for it is still used in the Xochimilco zone to the south of Mexico City, and may have originated with the Teotihuacanos in the Classic. It belongs to the general category of “raised field cultivation,” which is widespread in the New World tropics, and was in use among the lowland Classic Maya.

The first Aztec settlers on the island constructed canals in their marshy habitat by cutting layers of thick water vegetation from the surface and piling them up like mats to make their plots; from the bottom of the canals they spread mud over these green “rafts,” which were thoroughly anchored by planting willows all around. On this highly fertile plot all sorts of crops were raised by the most careful and loving hand cultivation. This is why Cortés states that half the houses in the capital were built up “on the lake,” and how swampy islands became united. Those houses on newly made chinampas were necessarily of light cane and thatch; on drier parts of the island, more substantial dwellings of stone and mortar were possible, some of two stories with flower-filled inner patios and gardens. Communication across the “streets” was by planks laid over the canals.

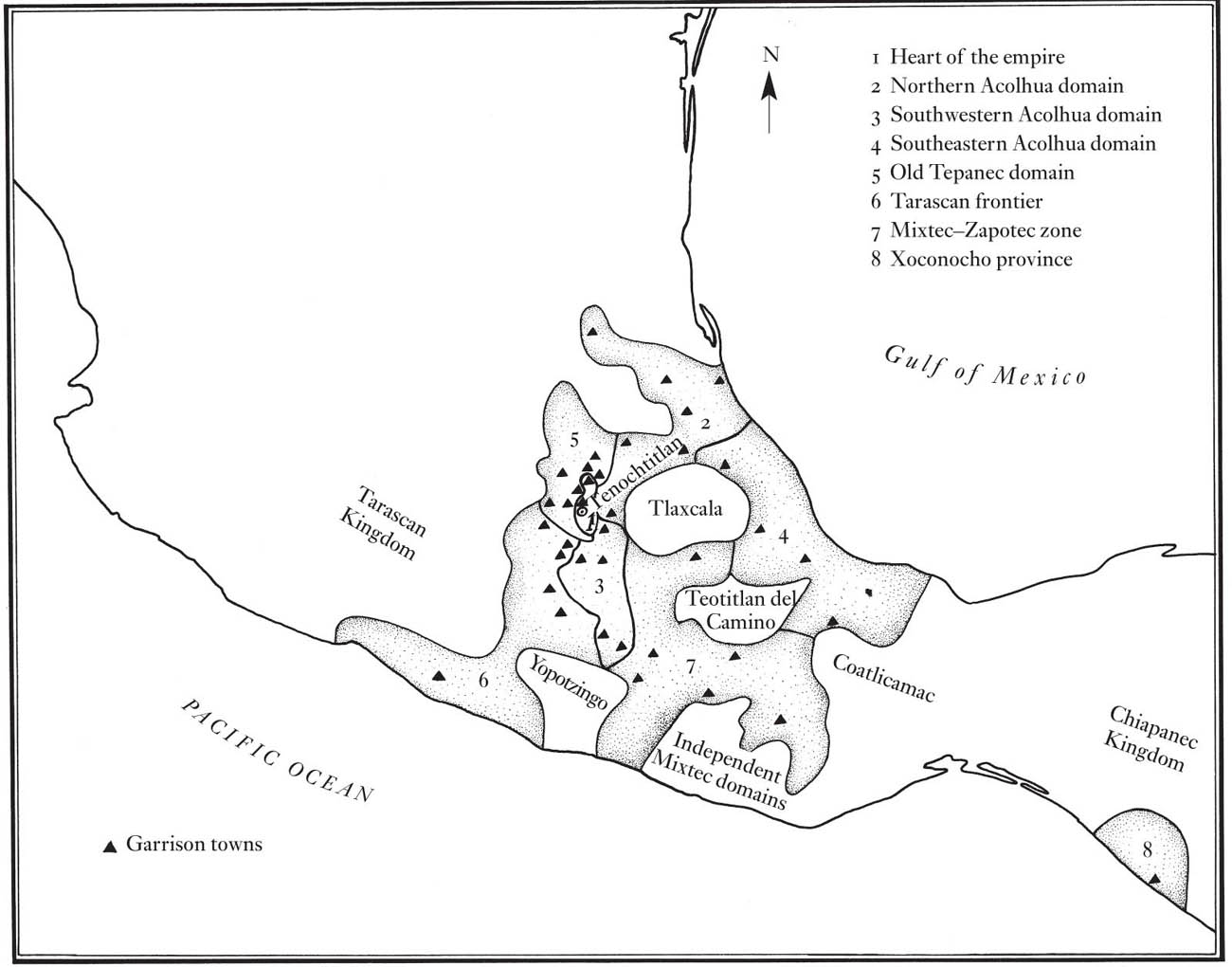

144 Extent of the Aztec empire in 1519. The provinces into which the Aztec domains were organized are indicated.

The greatest problem faced by the inhabitants of the island was the saltiness of the lake, at least in its eastern part. With no outlet, during floods those nitrous waters inundated and ruined the chinampas. To prevent this, the Texcocan poet-king Nezahualcoyotl bountifully constructed a 10-mile (16-km) long dike to seal off a spring-fed, freshwater lagoon for Tenochtitlan.

With its willows, green gardens, numerous flowers, and canals bustling with canoes, Tenochtitlan must have been of impressive beauty, as the Nahuatl poem suggests:

The city is spread out in circles of jade,

radiating flashes of light like quetzal plumes,

Beside it the lords are borne in boats:

over them extends a flowery mist.7

It is extraordinarily difficult to estimate the population of the capital in 1519. Many early sources say that there were about 60,000 houses, but none say how many persons there were. Basing his calculations on the Aztec tribute lists, Rudolf van Zantwijk estimates that there were enough foodstuffs in the warehouses of Tenochtitlan to support a population of 350,000, even without taking into account local chinampa production. The data which we have, however flimsy, suggest that Tenochtitlan (with Tlatelolco) had at least 200,000 to 300,000 inhabitants when Cortés marched in, five times the size of the contemporary London of Henry VIII. Quite a number of other cities of central Mexico, such as Texcoco, also had very large populations; all of Mexico between the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the Chichimec frontier had about 11,000,000 inhabitants, most of whom were under Aztec domination.

145 The Valley of Mexico in Aztec times.

The houses of the ordinary class of people, especially those who lived on the chinampa plots, were generally of reeds plastered with mud, and roofed with thatch; better-off people had dwellings of adobe bricks with flat roofs; while those of the wealthy were of stone masonry, also with flat roofs, and probably made up house complexes arranged around an inner court, like those of Tula. The highest officials dwelt in great palace complexes, the greatest of which were reserved for the ruler or Huei Tlatoani (“Great Speaker”) and for the descendants of his predecessors.

On the higher ground at the center of Tenochtitlan, the focal point of all the main highways which led in from the mainland, was the administrative and spiritual heart of the empire, and the conceptual center of the universe. This was the Sacred Precinct, a paved area surrounded by the Coatepantli (“Snake Wall”), and containing, according to Fray Bernardino de Sahagún – our great authority on all aspects of Aztec life – seventy-eight buildings; approximately forty of these are accounted for in the archaeological record. The Sacred Precinct was dominated by the double Temple of Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc (the Great Temple), its twin stairways reddened with the blood of sacrificed captives. Other temples were dedicated to the cults of Tezcatlipoca, his adversary Quetzalcoatl, and Xipe Totec, the god of springtime. A reminder of the purpose of the never-ending “Flowery War” was the tzompantli, or skull rack, on which were skewered for public exhibition thousands of human heads. Near it was a very large ball court, in which Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin was said to have played a game with and lost to the king of Texcoco on the truth of the latter’s prediction that the former’s kingdom would fall. The magnificent palaces of the Aztec royal line surrounded the Sacred Precinct.

146 The center of Tenochtitlan in 1519. This walled precinct was the home of several of the most important Aztec temples and pyramids and the site of many key rites. The space was anchored by the Templo Mayor (Great Temple), dedicated to the Aztec patron deity (Huitzilopochtli) and the Rain God (Tlaloc). The sculpture at the base of this pyramid recalled the victory of their patron deity. Just to the north is the Eagle’s House, associated with warriors and the ancient power of rulers. To the west of the Templo Mayor were the skull rack and ball court, an important ensemble for the presentation of ball game rites. The northwest corner contained the calmecac complex, where elite were trained in Aztec religious tradition, while outside the precinct to the south and west were the palaces of Aztec rulers.

Both in Tenochtitlan and in Tlatelolco proper were great marketplaces, very close to the main temples. The latter market was described by Bernal Díaz in superlative terms; Cortés says that it was twice as large as the main square of Salamanca, in Spain, and some of the soldiers who had been in Rome and Constantinople claimed that it was larger than any there. Every day over 60,000 souls were engaged in buying and selling in the Tlatelolco market, so many that there were market inspectors appointed by the ruler to check the honesty of transactions and to regulate prices. Thieves convicted in the market court were immediately punished by being beaten to death (Aztec law was draconian). As for “money,” cacao beans (which sometimes were counterfeited), cotton cloaks, and transparent quills filled with gold dust served that purpose. Befitting its role as the commercial center of an empire, in the Great Market of Tlatelolco one could buy luxury products of gold, silver, jade, turquoise, or feathers; clothing of all sorts; foods both cooked and unprepared; pottery, the most esteemed being lovely polychrome dishes and cups from Cholula; chocolate and vanilla; carpenter’s tools of copper; cane cigarettes, tobacco pipes, and aromatic cigars; and slaves, brought in by dealers from the slave center of Atzcapotzalco and exhibited in wooden cages. The market people had the obligation to furnish war provisions to the state, mainly maize in forms that would not spoil on long marches.

The basic unit of Aztec social organization in the heart of the empire was the calpolli (pl. calpoltin), a word meaning “big house.” Often mistakenly called a “clan” – which would imply real or fictive descent from a common ancestor – the calpolli has been defined by Rudolf van Zantwijk as a group of families related by kinship or proximity over a long period of time. Elite members of the group provided its commoner members with arable land and/or non-agricultural occupations, in return for which the commoners would perform various services for their chiefs and render them tribute. The calpolli was thus a localized, land-holding corporation, but it also had ritual functions in that it had its own temple and gods, and even an association with a day in the 260-day count. Its principal chief, the calpollec, was elected for life by the inhabitants, and confirmed in office by the ruler. There were more than eighty calpoltin in Tenochtitlan, some of which have actually persisted as traditional barrios near the center of modern Mexico City. The calpoltin were arranged into the four great quarters into which the Aztec city was divided, separated by imaginary north–south and east–west lines which met at the Sacred Precinct.

The vast bulk of the population in the cities, towns, and villages of the empire consisted of commoners or macehualtin (sing. macehualli). These worked lands belonging to the calpoltin; each family with its plot maintained rights over it as long as it did not lie unused for over two years at a time. Many of these farmers also had a calmil, or house garden, which was managed at the household level. The rural macehualtin formed the majority of commoners. These people lived in dispersed settlements, constructing small check dams and terrace systems to increase agricultural yield. The modest scale of rural dam and terrace systems suggests that they were organized by the macehualtin themselves, unlike the large-scale irrigation systems found throughout the empire that required state-level organization. Whether they had access to state-supported projects or not, all macehualtin were required to pay tribute to their overlords, the Aztec nobility.

Near the top of the social ladder were the noblemen or pipiltin (sing. pilli), who were all the sons of lords: “precious feathers from the wings of past kings,” as one source puts it. It was from their rank that the imperial administrators were drawn; these had the use of lands belonging to their office and also owned private lands. Yet the social stratification so apparent in Aztec life was not entirely rigid, for there were also cuauhpipiltin, “eagle nobles” – commoners who had distinguished themselves on the field of battle and who were rewarded for their gallantry with noble titles and with private lands.

Above the pipiltin, at the apex of the social pyramid, were the teteuhctin (sing. tecuhtli), the rulers of towns and cities; the emperor himself was a tecuhtli. These received the honorific suffix -tzin at the ends of their names, and were entitled to wear clothes of the utmost richness. From their palaces they exercised legal powers, and ensured that tribute payments were made to all appropriate levels of the imperial administration. As far as conquered territories were concerned, the Aztecs wisely followed a system of indirect rule, by leaving the indigenous tecuhtli and nobles in place, but demoting them to the status of middle- and lower-rank officials.

At the bottom of the social scale were the mayeque, bondsmen or serfs who tilled the estates of the noblemen. These, according to van Zantwijk, comprised about 30 percent of the empire’s population, and were often former macehualtin who had lost their rights either through conquest or through suppression of rebellion. A study by Edward Hicks shows that the produce from about one third of the land worked by a serf went to his lord, while the rest could be retained by himself and his family (although he was expected to pay tribute from this). Some mayeque occasionally became richer and more powerful than the macehualtin through the inheritance of tangible property and other rights.

Slaves or tlacohtin (“bought ones”) were persons who had not been able to meet their obligations, particularly gambling debts. Such individuals could pawn themselves for given lengths of time (including in perpetuity), or they might even be pawned by needy spouses or parents. The institution of slavery was closely defined under Aztec law: for instance, slaves could not be resold without their consent, unless they violated the rules frequently, in which case they might end up in the slave market. They were generally well treated; and often – as among the ancient Romans – they became domestic servants, farm laborers, and even estate managers. Some achieved considerable prosperity. Comely young female slaves could be taken by rulers as concubines, and were considered as suitable diplomatic gifts (witness the women presented to Cortés).

Although relatively small in number, the long-distance merchants or pochteca constituted a powerful group in Aztec society. These were of far higher status than the ordinary market-vendors, for the emperor treated them like nobility, and if one of them died on an expedition, he went to the paradise of the Sun God like a fallen warrior. The pochteca were directly responsible to the royal palace and the tlatoani, for whom they traveled into foreign territories many hundreds of miles from the capital, to obtain luxury goods such as precious quetzal feathers, amber, and the like for the use of the crown. Allied with the pochteca was a more specialized group, the oztomeca, who went disguised in the local garb and who spoke the local language; their task was to gather military intelligence as well as exotic goods. Like the businessmen-spies of modern days, the oztomeca were often the vanguard for the Aztec takeover of another nation, acting sometimes as agents-provocateurs.

Membership in the pochteca was hereditary. There were twelve merchants’ organizations or guilds, all located in the heart of the empire, and all under the control of the head merchants in Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco. The most important commerce of this kind linked the capital with the tropical coasts of southeast Mesoamerica, particularly the Putún Maya port-of-trade at Xicallanco on the Gulf of Mexico; a key nodal point was the Aztec garrison town of Tochtepec, in northern Oaxaca, from which human caravans were sent out to the hot country, and to which they returned. It is apparent from detailed descriptions given by Father Sahagún that the goods exported largely consisted of cotton mantles and other textiles from the royal warehouses which had been received as tribute, along with cast-gold jewelry fashioned by Tenochtitlan’s master craftsmen.

Because the pochteca could themselves pay taxes to the palace in luxury goods rather than the produce of their lands, and grew rich and powerful as a consequence, some have seen them as an entrepreneurial middle class in formation. But there were powerful sanctions against them flaunting their wealth: as an example, they had to creep into the city at night after a successful trading expedition, lest they arouse the jealousy of the ruler. There was an additional leveling mechanism operating here, as Rudolf van Zantwijk has stressed. As a merchant rose up the social ladder of the guild, the special ceremony that he was obligated to give on his return from abroad became more and more costly. One of these was a Song Feast, a lavish banquet for a large number of guests; as he achieved even higher office within the pochteca organization, the ritual would include not only another and even more grand banquet (at which presents would have to be given out), but the human sacrifice of slaves bought in the market.

While this was a highly honorable enterprise, it was also a highly dangerous one, and many died of disease or injury on the road, or were slain. Because of this, the activities of the pochteca were surrounded by ritual dictated by the solar calendar. They even had their own gods, in particular Xiuhtecuhtli, the Fire God, and Yacatecuhtli (“Nose Lord”), a deity with a Pinocchio-like nose, a traveler’s staff in one hand and a woven fan in the other.

The enculturation experience – turning an unformed human being into an Aztec – began at birth. After she had cut the umbilical cord, the midwife recited set speeches to the newborn. To an infant girl she would say:

Oh my dear child, oh my jewel, oh my quetzal feather, you have come to life, you have been born, you have come out upon the earth. Our lord created you, fashioned you, caused you to be born upon the earth, he by whom all live, God. We have awaited you, we who are your mothers, your fathers; and your aunts, your uncles, your relatives have awaited you; they wept, they were sad before you when you came to life, when you were born upon the earth.8

A boy was told that the house in which he was born was not a true home, but just a resting place, for he was a warrior: “your mission is to give the sun the blood of enemies to drink, and to feed Tlaltecuhtli, the earth, with their bodies,” in contrast to girls, who were admonished to be homebodies.

Baptism took place not long after birth, on an auspicious day in the 260-day calendar, with the midwife doing the washing and naming of the child. The sex roles were again emphasized, boys being given a miniature breech clout, a cape, a shield, and four arrows; and girls a little skirt (cueitl) and blouse (huipilli), along with weaving implements. The early Colonial Codex Mendoza shows that a child’s subsequent upbringing was Spartan and strict. Until the age of fifteen, education took place in the family, a boy at first going out with his father to gather firewood, and later learning how to fish, a girl learning how to spin, and later advancing to weaving, and the grinding of the nixtamal for tortillas. Punishments for infractions were drastic: a disobedient boy might be left out naked to the night cold, pricked with maguey spines, or held over burning chile peppers.

In 1519, the Aztecs may have been the only people in the world with universal schooling for both sexes. This began at fifteen for all boys and girls, and lasted until they were of marriageable age (about twenty). There were two kinds of schools, the calmecac and the telpochcalli. The calmecac was a seminary, generally attached to a specific temple, attended by the sons and daughters of the pipiltin, but also by some pochteca children; in it, the priest-teachers instructed the students in all aspects of Aztec religion, including the calendar, the rituals, the songs which were to be chanted over the sacred books, and certainly much of the glorious past of the Aztec nation. Like the English public school, having attended a calmecac was a prerequisite to holding any kind of high office in the Aztec administration. Those who really wanted to enter the priesthood then passed to a kind of theological graduate school termed the tlamacazcalli (“priest’s house”) for further training.

The telpochcalli or “House of Youths” was basically a military academy, attended by the offspring of macehualtin (the commoners) and presided over by Tezcatlipoca, the god of warriors. As in the calmecac, the sexes were strictly segregated, and females were here assigned to a cuicalco, or “House of Song.” Male students were trained in the martial arts, and could even take leave to accompany seasoned warriors as their squires on the field of battle, while girls seem to have concentrated on less bellicose subjects such as song and dance. Conditions in the male part of the academy seem to have been far less austere than in the calmecac, and some of our sources tell us that the cadets were often visited by ladies of pleasure in their communal quarters.

For commoners, marriage took place at around the age of twenty; one was expected to marry someone within one’s own calpolli. This union was considered to be a contract between families, not individuals, and was arranged by an old woman acting as go-between. This was a complicated matter, for consent had to be obtained not only from the prospective bride’s family, but also from the young man’s masters in the school he had attended. After an auspicious day in the 260-day calendar had been selected for the ceremony, there was an elaborate banquet in the bride’s house, when she was arrayed and painted for the event. The actual marriage took place at night. First the bride was placed on the back of an old woman and borne in a procession to the groom’s house by the light of torches. The young couple were placed on a mat spread before the hearth, they were given presents, and the union was finalized by the tying together of her blouse and his cloak, followed by feasting at which the old people were allowed to get drunk.

There may have been equality of the sexes in the sphere of education, but it was otherwise with matrimony. This being a male-oriented society, the new couple always made their home with the bridegroom’s family. Moreover, a man could take as many secondary wives or concubines as he could afford: great princes and lords had dozens of such wives, sometimes even hundreds, and Nezahualpilli, the tlatoani of Texcoco, was said to have had 2,000 (and 144 children)! On the other hand, women seem to have had equal rights in divorce, which was never easy in any circumstance.

The Triple Alliance and the empire

A glance at a map showing the Aztec dominions as they were in 1519 would disclose that while the empire spanned the area between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific, it by no means included all of Mesoamerica. Left in place within it were enemy states like Tlaxcallan (which was to provide tens of thousands of quisling troops for Cortés), Huexotzingo, and Chollolan (Cholula). Under Axayacatl (1469–1481), the Aztec armies had tried to conquer the Tarascans, and been repelled once and for all, while much of southeastern Veracruz remained free of Aztec control, as did the entire Maya area. Nevertheless, this was an empire equivalent to those of the Old World, with an enormous population held in a mighty system whose main purpose was to provide tribute to the Valley of Mexico.

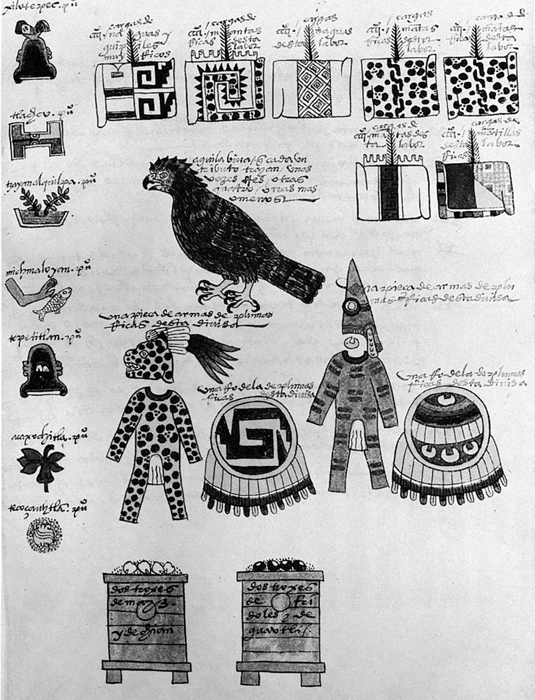

Nations which had fallen to Aztec arms and those of their allies in the Triple Alliance of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan were speedily organized as tribute-rendering provinces of the empire. Military governors in Aztec garrisons ensured that such tribute, which was very heavy indeed, was paid promptly and on fixed dates. Most of our sources state that on arrival in the Valley, tribute was distributed in a 2:2:1 ratio (Tenochtitlan and Texcoco got two-fifths each, and Tlacopan one-fifth). It is fortunate that the tribute list in Motecuhzoma’s state archives has survived in the form of copies (see ill. 147), for the Spaniards were also interested in what they could extract from the old Aztec provinces. Incredible as it may seem, each year Tenochtitlan received from all parts of the empire 7,000 tons of maize and 4,000 tons each of beans, chia seed, and grain amaranth, and no fewer than 2,000,000 cotton cloaks, as well as war costumes, shields, feather headdresses, and luxury products, such as amber, unobtainable in the central highlands. Certainly some of this loot, especially the cloaks, was farmed out by the royal treasury to the pochteca as barter goods to carry to distant ports of trade. But a good deal of the tribute acted as the main financial support of the state edifice, since in an essentially moneyless economy state servants had to be paid in goods and land, and artisans had to receive something for the fine products which they supplied to the palace. Each page of the tribute list covers one province, the various subject towns within it being listed vertically along the edge of the page. The names of these places are written by means of the rebus principle (the only form of script in use among the Aztecs, and employed exclusively for toponyms and personal names). Thus, the town called Mapachtepec (“Raccoon Hill”) would be expressed by a hand (ma-itl) grasping a bunch of Spanish moss (pach-tli), over a picture of a hill (tepe-tl). Aztec numbers on the list were given in a vigesimal (base 20) system: 1–19 by dots or occasionally by fingers, 20 by a flag, 400 by a sign which resembles a feather or fir tree, and 8,000 by a bag or pouch.

147 Page from the Codex Mendoza, a post-Conquest copy of an Aztec original. This is the tribute list of Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin. Pictured on this sheet is the biannual tribute due from the six towns of Xilotepec, an Otomi-speaking province northwest of the Valley of Mexico. Enumerated are women’s skirts and blouses, men’s mantles of various sorts, two warrior’s costumes with shields, four wooden cribs filled with maize, beans, and other foodstuffs, and an eagle.

Exempt from the payment of tribute were certain specialists like painters and singers, along with pipiltin who enjoyed the revenues from private lands, and outstanding warriors. Commoners, no matter where they were, had to pay both with maize ears and with labor, and each was expected to furnish one cotton mantle a year; merchants and ordinary artisans paid in the goods that they produced or that passed through their hands.

As the scholar Fernando Horcasitas once said, the Aztec empire was not so much an empire in the Roman or British sense as an economic empire based on the provision of tribute, paid in full and on a regular basis. Obviously, some of the peoples participating under this arrangement were unwilling partners in the system, and chafed under the Aztec yoke. There was thus an inherent weakness in the empire that Cortés was quick to perceive and to exploit.

The Aztec emperor was in every sense an absolute ruler, although only in certain domains. His Nahuatl title was Huei Tlatoani or “Great Speaker”; as the researches of Rudolf van Zantwijk have made clear, his function, like that of the “talking chiefs” among North American tribes, was principally to deal with the external side of the Aztec polity – warfare, tribute, and diplomacy. His counterpart handling the internal affairs of Mexico-Tenochtitlan was the man who held the office of Cihuacoatl or “Female Snake.” Based on an Aztec female deity, the very title celebrates the opposition of male and female principles in the philosophy of dualism so dear to the Aztecs. This man acted as a kind of grand vizier, and was always a close relative of the Huei Tlatoani; the most famous Cihuacoatl of all was the great Tlacaelel, who transformed the Aztec realm from a kingdom into an empire.

The Huei Tlatoani was elected from the royal lineage by a council composed of the nobles, chief priests, and top war officers; at the same time, the four principal lords who were to act as his executive arm were also chosen. All sources agree on the openness of the process but, while many names were advanced during the convocation, only one was put forth by the council. The exact rules of Aztec dynastic succession are still being debated by scholars, but during the last hundred years of the empire brothers seem to have inherited the office more often than sons.

On his installation, the new king was taken by the chief priests to pay homage at the temple of the national god, Huitzilopochtli; while he censed the sacred image, the masses of citizens waited expectantly below, in a din caused by the blowing of shell trumpets. Four days were spent by the king in meditation and fasting in the temple, which included prayers and speeches in honor of Tezcatlipoca, the patron deity of the royal house. Before the image of this all-powerful god the new king stood naked, emphasizing his utter unworthiness in speeches like this:

O master, O our lord, O lord of the near, of the nigh, O night, O wind… Poor am I. In what manner shall I act for thy city? In what manner shall I act for the governed, for the vassals [macehualtin]? For I am blind, I am deaf, I am an imbecile, and in excrement, in filth hath my lifetime been… Perhaps thou mistaketh me for another; perhaps thou seekest another in my stead.9

Then the Huei Tlatoani was escorted to his palace, which stood adjacent to the Sacred Precinct. To his coronation banquet came even the kings of distant lands, such as the rulers of the Tarascan kingdom, the king of the Totonacs (a puppet prince), and great personages from as far away as Tehuantepec.

The descriptions of the Spaniards make it clear that the Huei Tlatoani was semi-divine. Even great lords who entered into his presence approached in plain garments, heads bowed, without looking on his face. Everywhere he went, he was borne on the shoulders of noblemen in a litter covered with precious feathers. If he walked, nobles swept the way and covered the ground with cloths so that his feet would not touch the ground. When Motecuhzoma ate, he was shielded from onlookers by a gilt screen. No fewer than several hundred dishes were offered at each meal for his choosing by young maidens; during his repast he was entertained by buffoons, dwarfs, jugglers, and tumblers.

Motecuhzoma’s gardens and pleasure palaces amazed the Spaniards. The royal aviary had ten large rooms with pools of salt and fresh water, housing birds of both lake and sea, above which were galleries bordered by hanging gardens for the imperial promenade. Another building was the royal zoo, staffed by trained veterinarians, in which were exhibited in cages animals from all parts of his realm – jaguars from the lowlands, pumas from the mountains, foxes, and so forth, making an unearthly clamor with their roars and howls. Carefully tended by servants, many kinds of deformed persons and monstrosities inhabited his private sideshow, each with his own room.

Less frivolous activities of the royal household included separate courts of justice for noblemen (and warriors) and for commoners; the overseeing by stewards of the palace storehouse; the maintenance of the state arsenal, officers’ quarters, and the military academy; and the management of the empire-wide tribute system.

All of these state functions, the Aztec war machine, and the Aztec economy itself, ultimately rested on the agricultural basis of the Mexican peoples – the farming of maize, beans, squash, chile peppers, tomatoes, amaranth, chia, and a host of other cultigens. Thousands of canoes daily crowded the great lake, bearing these products to the capital either as direct tribute or as merchandise to be traded for craft items and other necessities in the marketplaces. A tremendous surplus for the use of the city was extracted from the rich chinampas fringing the shallow lake and from fields nearby, while the upper slopes of the surrounding hills were probably largely given over to the cultivation of maguey, the source of the mildly alcoholic beverage so important to Aztec culture.

Most of the Aztec people, from nobles to serfs, were very well fed, although Lucullan repasts and other excesses were proscribed by the puritanical Aztec ethic. Much of the diet of ordinary citizens consisted of tortillas dipped in a molli or sauce made of chiles ground with water; maize could also be taken in the form of steamed tamales, to which could be added ground or whole beans, but unlike their modern counterparts, these contained no fat or grease. Sahagún’s informants gave him a long list of dishes with their ingredients, and these show that the Aztec cuisine was extremely sophisticated: for example, there were dozens of ways to prepare tamales, not just one. Meat and fish dishes were for the elite, or were reserved for feast days, while poorer people ate large quantities of greens instead. Although some of these are not to modern taste, many animal and plant species entered the Aztec cuisine, such as the axolotl, a large larval salamander found in chinampa canals which could be stewed in a sauce of yellow chiles, or tadpoles prepared in a variety of styles. Insects, in the form of eggs, larvae, and adults, were widely consumed, as was tecuilatl, a scum-like algae (Spirulina sp.) gathered from lake margins; this latter was pressed into cakes. A wide variety of fruits, from both the highlands and the tropical lowlands, were available in the markets, and highly appreciated.

Amaranth occupied a special place in the Aztec diet. This eminently nutritious grain crop was imported into the capital in large quantities, but it was destined not so much for the kitchens of ordinary folk as for ceremonial use: it was mixed with ground maize, along with honey or maguey sap, formed into idols of the great god Huitzilopochtli, and consumed in this manner on his feast days – to the horror of the Spanish priests, who saw this as a travesty of Holy Communion!

Maize could be consumed not only as tortillas and tamales, but also in liquid form, as a maize gruel called atolli; another kind of maize drink called pozolli was made from slightly fermented maize dough; both could be taken to the fields in gourd containers for the repast of farmers. Chocolate drinks were generally reserved for the elite and the wealthy, for the bean was expensive. Chocolate could be prepared in a variety of ways, with an array of flavors (such as chile pepper, vanilla, and other spices); it could even be mixed with atolli. As might be expected, given their ethic of moderation and austerity, the Aztecs were ambivalent about octli (called by the Spaniards pulque), the fermented sap of the maguey plant. One was not supposed to drink more than four cups during a feast, and drunkenness was punished with severity and even death; although old people were released from this prohibition and allowed to get thoroughly inebriated whenever they pleased. Nonetheless, octli played a major role in Aztec ritual, and there was a whole group of octli gods, as well as a major goddess of the maguey plant, about whom a mythic cycle was created.

The Aztec army, like armies everywhere, traveled on its stomach, and the Aztec military successes which resulted in their empire were in part the outcome of their ability to supply their forces with food – principally dried tortillas – wherever they went. The main goal of the Aztec state was war. Every able-bodied man was expected to bear arms, even the priests and the long-distance merchants, the latter fighting in their own units while ostensibly on trading expeditions. To the Aztecs, there was no activity more glorious than to furnish captives or to die oneself for Huitzilopochtli:

The battlefield is the place:

where one toasts the divine liquor in war,

where are stained red the divine eagles,

where the jaguars howl,

where all kinds of precious stones rain from ornaments,

where wave headdresses rich with fine plumes,

where princes are smashed to bits.10

In the rich imagery of Nahuatl song, the blood-stained battlefield was described as an immense plain covered by flowers, and lucky was he who perished on it:

There is nothing like death in war,

nothing like the flowery death

so precious to Him who gives life:

far off I see it: my heart yearns for it!11

Aztec weapons were the terrible sword-club (macuahuitl), with side grooves set with razor-sharp obsidian blades; spears, the heads of which were also set with blades; and barbed and fletched darts hurled from the atlatl. Seasoned Aztec warriors were gorgeously arrayed in costumes of jaguar skins or suits covered with eagle feathers, symbolizing the knightly orders; for defense, Aztec troops were sometimes clad in a quilted cotton tunic and always carried a round shield of wood or reeds covered with hide, often magnificently decorated with colored designs in feathers. While the battle raged, high-ranking officers could be identified by ensigns worn on the shoulders – towering constructions of reeds, feathers, and the like, which made it all too easy for the soldiers of Cortés to identify and destroy them.

War strategy included the gathering of intelligence and compilation of maps. On the field of battle, the ranks of the army were arranged by generals. Attacks were spearheaded by an elite corps of veteran warriors, followed by the bulk of the army, to the sound of shell trumpets blown by priests. The idea was not only to destroy the enemy town but also to isolate and capture as many of the enemy as possible for transport to the rear and eventual sacrifice in the capital.

Although the Aztec authority Henry Nicholson has said that among the Aztecs “human sacrifice…was practiced on a scale not even approached by any other ritual system in the history of the world,” many scholars are now convinced that this scale was immensely exaggerated by the Spaniards to justify their own violence and aggression against the New World natives. One of our Spanish sources, for example, reports that over 80,000 victims, all of them war captives, were dispatched to celebrate the dedication of the Great Temple in 1487, probably a physical impossibility. Yet it is true, as Nicholson has maintained, that “some type of death sacrifice normally accompanied all important rituals,” a custom that surely goes back to the Olmecs; it was practiced in Teotihuacan, as the warrior sacrifices of the Temple of Quetzalcoatl so abundantly prove. In all likelihood, several hundreds, perhaps even a few thousand, young men so lost their lives in the Aztec capital each year, but there is no way to test this.

The victims were ideally enemy warriors; when an Aztec took a captive in action, he said to him, “Here is my well-beloved son,” and the captive responded “Here is my revered father,” establishing the kind of fictive kinship that characterized the warrior-captive relationship in the New World from the Tupinambá of Brazil to the Iroquois of New York State. All warriors believed that they were destined to die this way, being transformed on death into hummingbirds which went to join the Sun God in his celestial paradise.

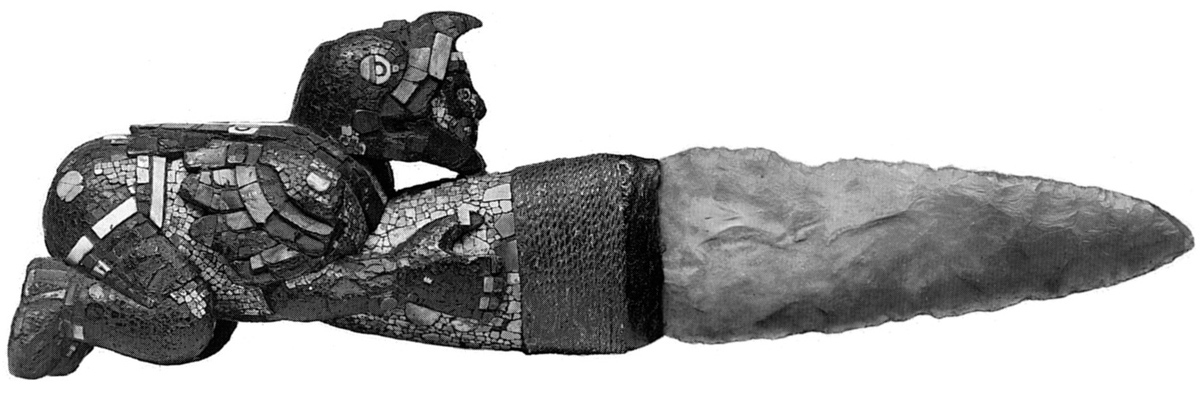

After the victim had been ritually bathed, there were five possible modes of sacrifice. The usual one was by stretching the prone body over a sacrificial stone, opening the chest with a knife of flint or obsidian, and ripping out the heart, which was then offered to the gods in a cuauhxicalli, or “eagle vessel” of carved stone. A second was decapitation, but this was customarily reserved for female victims impersonating goddesses. A third method was gladiatorial sacrifice, in which the war captive was tethered to a round stone, and forced to defend himself against a seasoned warrior with a sword-club which lacked the usual obsidian blades; as Father Durán laconically says, “Whether one defended himself well or whether one fought badly, death was inevitable.” Sacrifice of warriors strapped to scaffolds and shot with darts or arrows was another. And finally, there was heart sacrifice after the captive had been thrown repeatedly into a fire, probably the most unpleasant end of all.

It is incontrovertible that some of these victims ended up by being eaten ritually. That said, the sensational theory put forth by Michael Harner, that the Aztec elite practiced cannibalism on an allegedly massive scale so as to monopolize protein in a protein-poor environment, fails on two grounds: 1) there were abundant sources of protein available to the residents of the Valley of Mexico, not the least of which was Spirulina lake scum; and 2) a close reading of the historical records demonstrates that human flesh was eaten very sparingly and only during tightly controlled rituals – in fact, the practice was more like a form of communion than a cannibal feast. Archaeological evidence for the largest instance of cannibalistic rites occurs not in Pre-Columbian times but during the upheavals of the Conquest, where at Tecuaque a Spanish caravan consisting of approximately 500 persons was ambushed, sacrificed, and at least some of the victims then cooked and eaten over the course of several months. This rather spectacular episode was likely carried out in revenge for the murder of a high-ranking Aztec dignitary.

Aztec mythology and religious organization are so incredibly complex that little justice can be given them in the space of this chapter. The data that we have from the early sources, particularly from the pictorial books and from Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, are more complete in this respect than for any other Mesoamerican people.

The Aztec concept of the supernatural world was a result of the reconciliation by mystic intellectuals of the tribal gods of their own people to the far richer cosmogony of the older civilizations of Mexico, welding both into a single great system. The bewildering multiplicity of Mexican gods was to these thinkers but an embodiment of one cosmic principle of duality: the unity of opposites, as personified in the great bisexual creator deity, Ometeotl or “Dual Divinity.” In Aztec philosophy, this was the only reality, all else being illusion. Ometeotl presided over a layered universe, dwelling in the thirteenth and uppermost heaven, while various celestial phenomena such as the sun, moon, stars, comets, and winds existed in lower heavens. Beneath the surface of the earth were nine stratified underworlds, through which the souls of the dead had to pass in a perilous journey until reaching extinction in the deepest level, Mictlan Opochcalocan, “The Land of the Dead, Where the Streets Are on the Left.” This was presided over by another dual divinity, the dread “Lord and Lady of the Land of the Dead,” the infernal counterpart of Ometeotl.

Out of the sexual opposition embodied in Ometeotl were born the four Tezcatlipocas. Like all the Mesoamericans and many other American Indian groups as well, the Aztecs thought of the surface of our world in terms of the four cardinal directions, each of which was assigned a specific color and a specific tree on the upper branches of which perched a distinctive bird. Where the central axis passed through the earth was the Old Fire God, an avatar of Ometeotl since his epithet was “Mother of the Gods, Father of the Gods.” Of these four offspring, the greatest was the Black Tezcatlipoca (“Smoking Mirror”) of the north, the god of war and sorcery, and the patron deity of the royal house, to whom the new emperor prayed on his succession to office. He was everywhere, in all things, and could see into one’s heart by means of his magic mirror. This, the “real” Tezcatlipoca, was the giver and taker away of life and riches, and was much feared. The White Tezcatlipoca of the west was the familiar Quetzalcoatl, the Lord of Life and the patron of the priestly order.

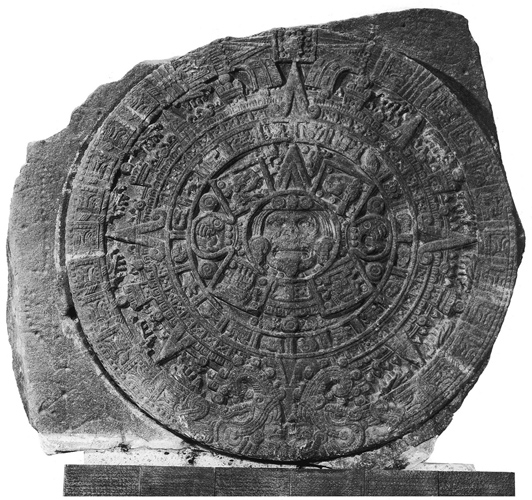

Visually expressed on the famous Calendar Stone (see ill. 148) and other Aztec monuments was the belief that the world had gone through four cosmic ages or Suns (like the Hindu kalpas), each destroyed by a cataclysm; this process of repeated creations and destructions was the result of the titanic struggle between the Black Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl, in each of which one or the other would be triumphant and would dominate the next age. The previous age perished in floods, when the sky fell on the earth and all became dark. We ourselves live in the Fifth Sun, which was created at Teotihuacan when the gods gathered there to consider what to do. After each had declined in turn the honor of sacrificing himself to begin the world anew, the least and most miserable of them, “The Poxy (or Purulent) One,” hurled himself in a great fire and rose up to the sky as the new Sun. Another god then repeated this altruistic act, rising as the Moon; but this luminary was casting rays as bright as the Sun, so to dim it the gods hurled a rabbit across the Moon’s face, where it may still be seen.

148 Aztec Calendar Stone, part of the sculptural program around the Great Temple. The interior contains glyphs referring to the five cosmic ages, surrounded by the twenty day signs of the sacred calendar. A central devouring deity represents the need for sacrifice.

Human beings had existed in the previous world, but they had perished. To recreate them, Quetzalcoatl made a perilous journey into the Underworld, stealing their bones from Mictlantecuhtli, “Lord of the Land of the Dead.” When he reached the earth’s surface, these were ground up in a bowl, and the gods shed blood over them from their perforated members. From this deed, people were born, but they lacked the sustenance that the gods had decreed for them: maize, which had been hidden by the gods inside a magic mountain. Here again Quetzalcoatl came to the rescue: by turning himself into an ant, he entered the mountain and stole the grains which were to nurture the Aztec people.

Central to the concepts of the Aztec destiny codified by Tlacaelel was the official cult of Huitzilopochtli, the Blue Tezcatlipoca of the south. The result of a miraculous birth from Coatlicue (an aspect of the female side of Ometeotl), he was the tutelary divinity of the Aztec people; the terrible warrior god of the sun, he needed the hearts and blood of sacrificed human warriors so that he would rise from the east each morning after a nightly trip through the Underworld.

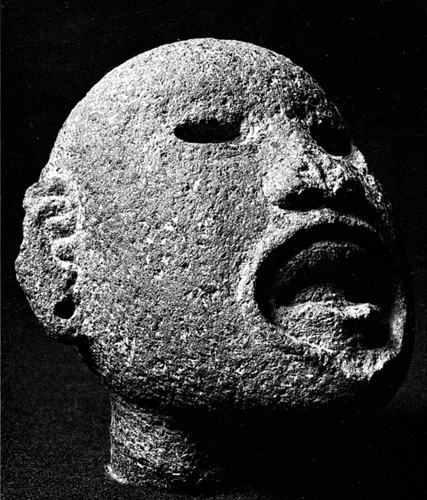

On the east was the Red Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec “Our Lord the Flayed One.” He was the god of spring and the renewal of the vegetation, impersonated by priests and those doing penance, wearing the skin of a flayed captive - the new skin symbolizing the “skin” of new vegetation which the earth puts on when the rains come. At the end of twenty days the god impersonator could take the skin off, but by this time he “stank like a dead dog,” as one source tells us.

149 Stone head from the Great Temple excavations of Xipe Totec, god of spring and fertility, wearing the flayed skin of a sacrificial victim. Ht 4 ⅔ in (11.9 cm).

Tlaloc (see ill. 157) was another nature god, the source of rain and lightning and thus central to Aztec agricultural rites; he could also be quadruple, so that there were black, white, blue, and red Tlalocs, but he was generally depicted as blue-colored, with serpent-like fangs and goggles over the eyes. One of the more horrifying of Aztec practices was the sacrifice of small children on mountain tops to bring rain at the end of the dry season, in propitiation of Tlaloc. It was said that the more the children cried, the more the Rain God was pleased. His cult still survives today among central Mexican peasants, although humans have probably not been sacrificed to him since early Colonial days.

The cults were presided over by a celibate clergy. Every priest had been to a seminary at which he was instructed in the complicated ritual that he was expected to carry out daily. Their long, unkempt hair clotted with blood, their ears and members shredded from self-mutilations effected with agave thorns and sting-ray spines, smelling of death and putrefaction, they must have been awesome spokesmen for the Aztec gods.

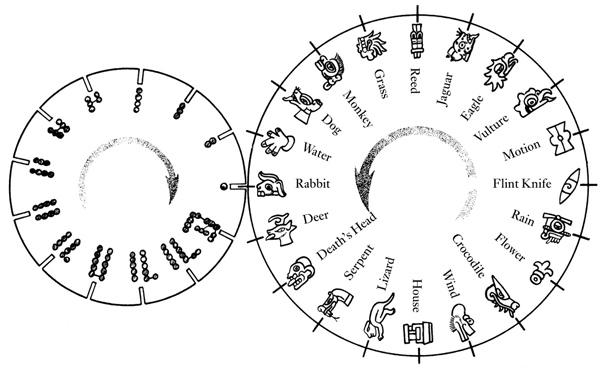

The daily life of all Aztecs was bound up with the ceremonies dictated by the machine-like workings of their calendar (see ill. 150). The Almanac Year (tonalpohualli) of 260 days was the result of the intermeshing of 20 days (given names like Crocodile, Wind, House, Lizard, etc.) with the numbers 1 to 13, expressed in their books by dots only. To all individuals, each day in the tonalpohualli brought good or evil tidings in accordance with the prognostications of the priests; but the bad effects could be mitigated, so that if a child was born on an unfavorable day, his naming ceremony could be postponed to a better one. For each of the twenty 13-day “weeks” there were special rites and presiding gods; there were also supernatural birds ruling over each of the 13 days of the “week,” and a constantly repeating series of 9 gods who reigned during the night.

150 Schematic representation of the tonalpohualli or 260-day period of the Aztecs. The 20 named days intermesh with the numbers 1 to 13.

The Solar Year was made up of 18 named months of 20 days each, with an unlucky and highly dangerous period of 5 extra days before the commencement of the next year. Again, every month had its own special ceremonies in which all the citizens of the capital participated; given this kind of cycle, it is hardly surprising that the months were closely correlated with the agricultural year, but there must have been a constant slippage in this respect since neither the Aztecs nor any other Mesoamericans used Leap Years or any other kind of intercalation to adjust for the fact that the true length of the year is a quarter-day longer than 365 days. The Solar Years were named after one of the four possible names of the Almanac Year that could fall on the last day of the eighteenth month, along with its accompanying numerical coefficient.

Observations of the sun, moon, planets, and stars were carried out by the Aztec priests, and apparently even by the rulers, but they were not so advanced in this respect as the Maya. After the sun, the most important heavenly body to the Aztecs was Venus, particularly in its first appearance, or heliacal rising, as Morning Star in the east, which they calculated took place every 584 days (the true figure is 583.92 days). While the Morning Star was thought to be the apotheosis of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, ruler of Tula, its heliacal rising was viewed as fraught with danger and they feared its rays at that time. It is a remarkable fact that every 104 Solar Years, all parts of their calendar coincided: the Almanac Year of 260 days, the Solar Year of 365 days, and the 584-day synodic period of Venus.

It was impressed on the Aztec mind that the close of every 52-year Calendar Round was a point at which the Fifth Sun could be destroyed. On this day, all fires in every temple, palace, and household were extinguished. On the Hill of the Star, just east of Colhuacan in the Valley of Mexico, the Fire Priests anxiously watched to see if the Pleiades would cross the meridian at midnight on this date; if they did, then the universe would continue. A fire was kindled on fire-sticks in the newly opened breast of a captive, and the glowing embers were carried by runners to every part of the Aztec realm.

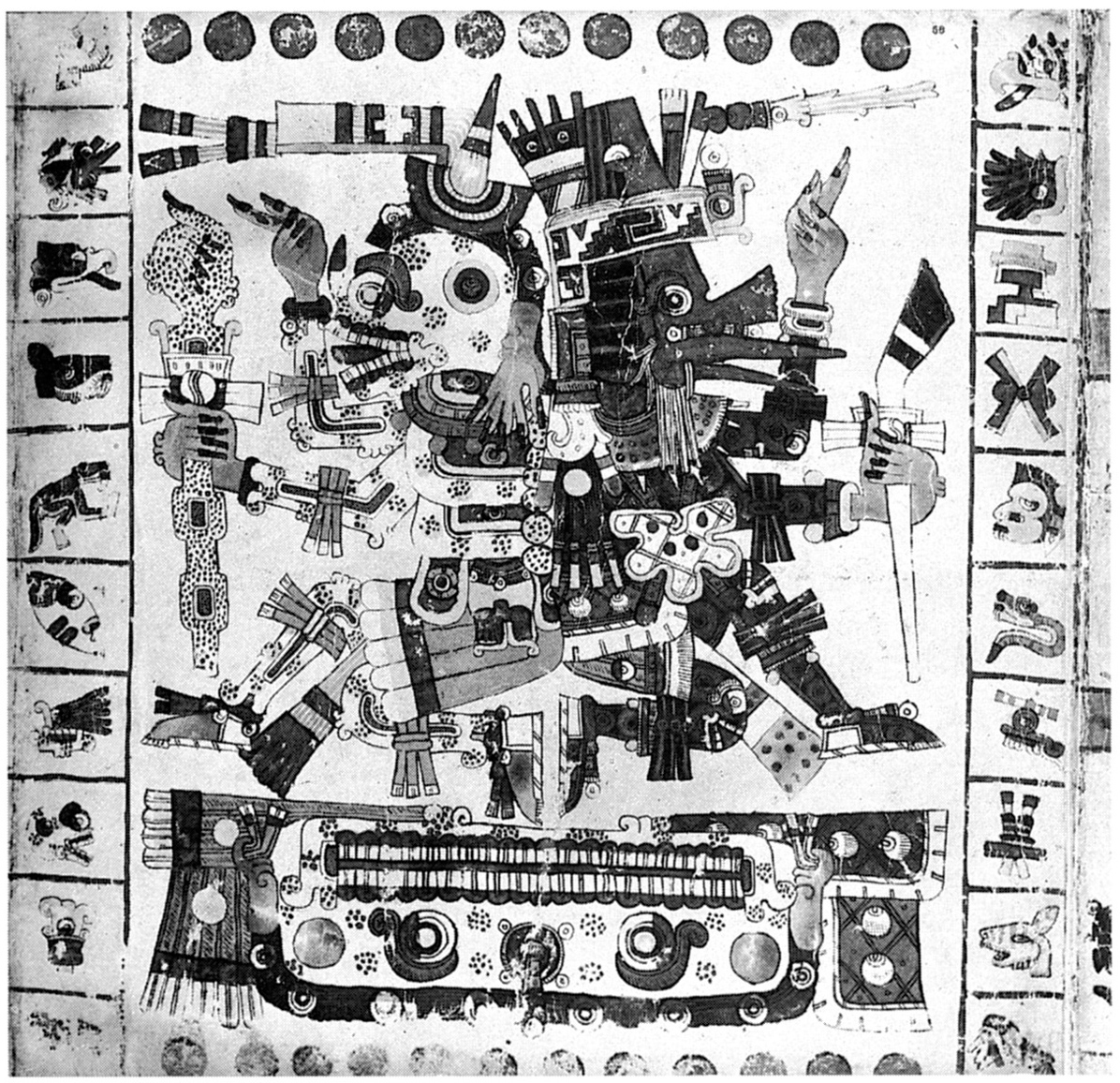

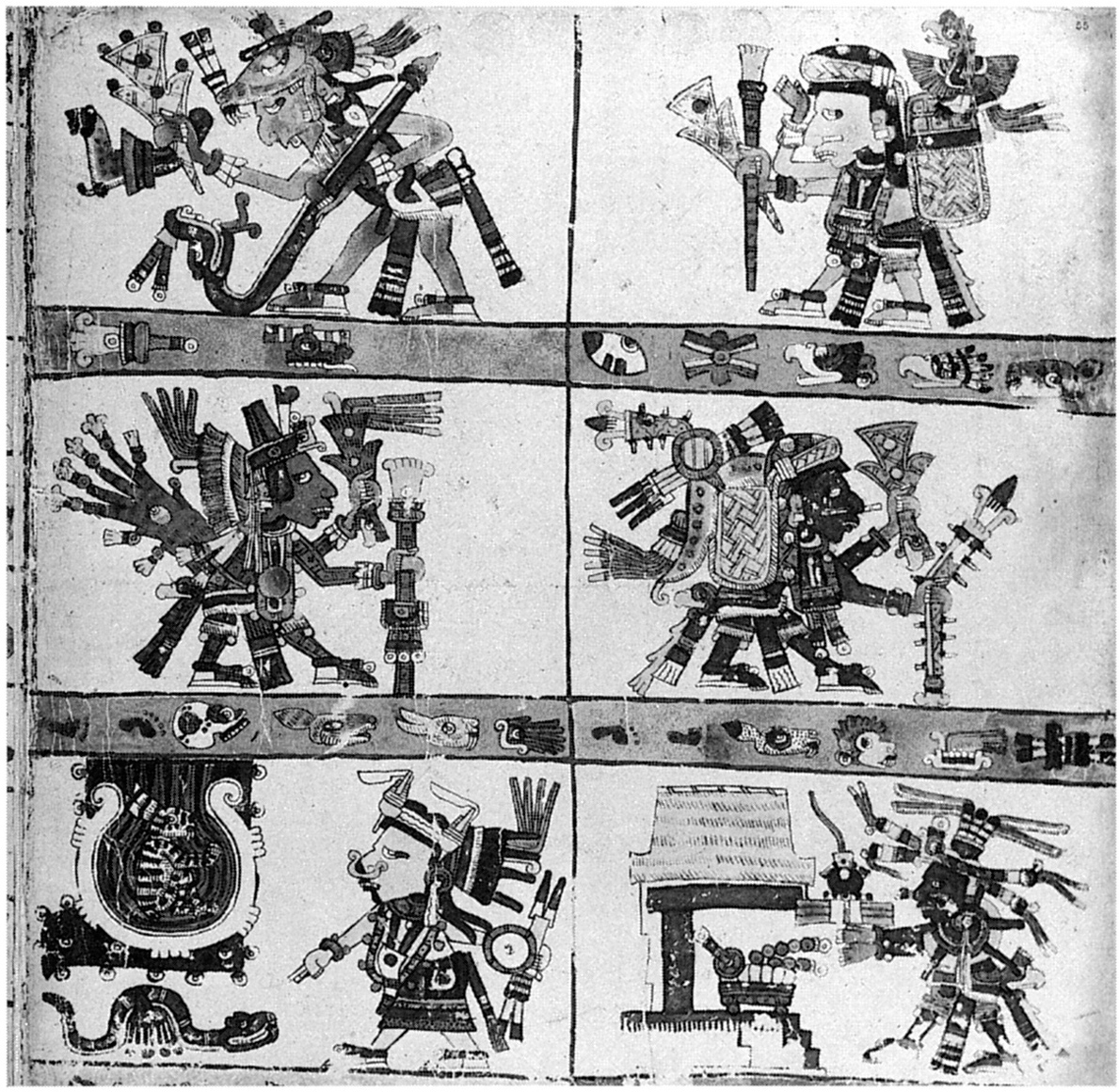

All this complex information was recorded in pictorial codices, folding-screen books of deerskin or bark paper, kept in the temples and seminaries by the priests (see ills 151 and 152). The state archives also included economic accounts, maps, and, possibly, historical works. Given the somewhat rudimentary nature of the Aztec script, such books must have been mainly mnemonic aids, to assist the priests in bringing to mind the details of immensely long oral recitations. It is a sad fact that, as a result of the massive book-burnings carried out by the Franciscan friars following the Conquest, no truly Aztec codices from the Valley of Mexico have survived. The Codex Borbonicus, preserved in the library of the National Assembly in Paris, while dating from the very early Colonial period, probably comes close to what these may have looked like.

151 Page from the Codex Borgia, now in the Vatican Library. This, the finest of all Mexican manuscripts, might have been painted in Cholula, Puebla. The codex is deerskin and is folded in screen fashion; it is 33 ft 9 in (10.3 m) long and 10 ⅔ in (27 cm) wide. The scene illustrates the dual aspect of existence, the Death God back-to-back with Quetzalcoatl, the Lord of Life. Around the edge of the page are various days from the 260-day count, one half assigned to the rule of one god and one half to the other. Mixteca-Puebla culture, Late Post-Classic period.

152 Page from the Codex Borgia. Depicted is the host of the night sky. Represented here, reading from left to right and from top to bottom, are Mixcoatl, the Milky Way; the Traveler of the Southern Sky; Xolotl, the planet Venus; the Traveler of the Northern Sky; the Moon Goddess, before the moon; Tonatiuh, the Sun. Mixteca-Puebla culture, Late Post-Classic period.

The ritual round must have provided year-long excitement and meaning to the life of the ordinary citizen of Tenochtitlan, with feasts, decoration of the idols, and dances and songs to the accompaniment of two-toned slit drums, upright drums, conch-shell trumpets, rattles, and flutes. Homage to the gods prescribed individual penances and burning of blood-spattered paper, burning of perfumed copal incense, and immolation of hundreds or thousands of human captives yearly.

As has been said, the souls of warriors who had died under the sacrificial knife or on the field of battle went not to the Land of the Dead in the Underworld, but directly to the Paradise of the Sun God. Curiously, so did the dread spirits of women who died in childbirth (for they also had fought their “warrior” and lost); they rose dutifully from the west each day to greet the sun at noon, conducting it into the nether regions. Others who also avoided extinction in Mictlan were those who had died in some manner connected with the Rain God: by lightning, drowning, or sufferers from dropsy and gout. They ascended to the Paradise of Tlaloc, where they spent an idyllic afterlife among flowers, butterflies, and other heavenly delights.

153 Sacrificial knife of flint with mosaic-incrusted handle in the form of an Eagle Knight. Aztec culture, Late Post-Classic period. Length 11 ¾ in (30 cm).

Most famous among the Aztec sacrifices was that of the handsome young captive annually chosen to impersonate the god Tezcatlipoca. For one year he lived a life of honor, worshipped literally as the embodiment of the deity; towards the end, he was given four beautiful maidens as his mistresses. Finally, he left them sadly, mounted the steps of the temple, smashing one by one the clay flutes on which he had played in his brief moment of glory, then was flung on his back so that the flint dagger might be plunged into his breast.

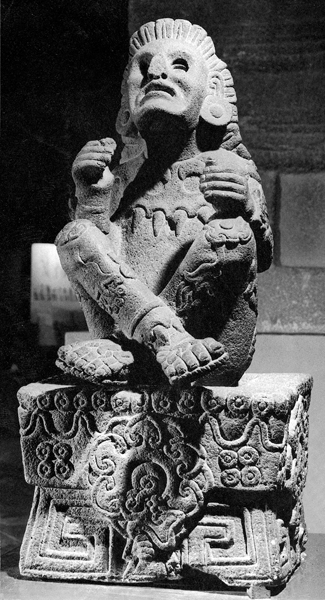

The Aztecs were the greatest sculptors seen in Mexico since the demise of the Olmec civilization, capable of turning out masterpieces from tiny works in semi-precious stones like rock crystal and amethyst, to truly monumental carvings. To some eyes, Aztec sculpture may be repulsive, and there is no doubt that the colossal figures of gods like Coatlicue (see ill. 154) may be terrifying, but there is no denying their awesome power. Power is also reflected in the more “realistic” works such as the seated stone figure of Xochipilli (“Prince of Flowers”), the god of love and summertime, which continue traditions of workmanship perfected by the Toltecs (see ill. 155). Or, in the same vein, the lovely sculptured drum from Malinalco (see ill. 156), which recalls the Nahuatl war song:

The earth shakes: the Mexica begins his song:

He makes the Eagles and Jaguars dance with him!

Come to see the Huexotzinca:

On the dais of the Eagle he shouts out,

Loudly cries the Mexica.12

154 Colossal statue of Coatlicue or Tzitzimitl. The head has been severed from the body, and two serpents rise from the neck, meeting to form a face. Her necklace is fashioned from human hearts and hands, with a pendant skull. The skirt is a web of writhing snakes. Since the goddess feeds on human corpses, her hands and feet are tipped with monstrous claws. Aztec, Late Post-Classic period. Ht 8 ft 2 in (2.5 m).

155 Statue of Xochipilli, the Aztec “Prince of Flowers,” patron god of dances, games, and love, and symbol of summertime. The god sits crosslegged on a temple platform which is adorned with a flower, butterflies, and clusters of four dots signifying the heat of the sun. He wears a mask and is decorated with hallucinogenic mushrooms and flowers from psychotropic plants, as well as with animal skins. Aztec, Late Post-Classic period. Ht of figure with base 3 ft 11 in (1.2 m).

156 Carved wooden drum (huehuetl) from Malinalco, State of Mexico. The drum is carved in relief with scenes representing the “Flowery,” or Sacred, War of the Aztecs, symbolized by dancing eagles and jaguars, the sign 4 Motion (the present age of the world), and, as seen here in the upper register, the figure of the Sun as an eagle. Aztec, Late Post-Classic period. Ht 3 ft 9 in (1.15 m).

Aztec artisans in Tenochtitlan were arranged in an approximation of guilds and were famous for their fine work in feather mosaics; but they were hardly rivals to the great craftsmen of the Cholula area, who under influence from the Mixtecs in the south, Aztecs in the north, and possibly Tarascans in the west produced the magnificent Mixteca-Puebla style. Motecuhzoma himself would eat only from cups and plates of Cholula ware, and it is certain that much of the goldwork as well as practically all the fine masks and other ceremonial paraphernalia of wood encrusted with turquoise mosaic were also manufactured there. The stupendous collection of mosaic pieces once in the hands of Charles V and now in the British Museum, in Florence, and in Rome bears eloquent testimony to late Mexican workmanship in this medium, although most examples are said to have been consumed in the pietre dure “laboratories” of Florence in the early nineteenth century.

Aztec architecture was primarily ecclesiastical, rather than secular in nature. The leveling of the Sacred Precincts of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco by the Spaniards for their own administrative buildings, cathedral, and churches destroyed all but the foundations of the major Aztec temples, but some idea can be gained of their magnificence by those that remain elsewhere in the Valley of Mexico, such as the huge double temple at Tenayuca, or the wonderful rock-carved sanctuary at Malinalco (see ills 158 and 159), circular and therefore certainly sacred to Quetzalcoatl.

157 Late Post-Classic effigy censer, mixing aspects of the Rain God Tlaloc and a corn god.

158 Facade of Temple I, Malinalco, State of Mexico, a circular temple cut from the living rock. The work was carried out under orders from the Aztec emperors Ahuitzotl and Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, between 1501 and 1515 (in the Late Post-Classic period). The outer wall is now about 9 ft 10 in (3 m) high. Entrance to the interior was gained through a giant serpent face. Within can be seen an outspread eagle in the center of the floor and above it a feline and other eagles stretched out on a circular banquette.

159 Temple I at Malinalco as it is today, with its reconstructed thatched roof.

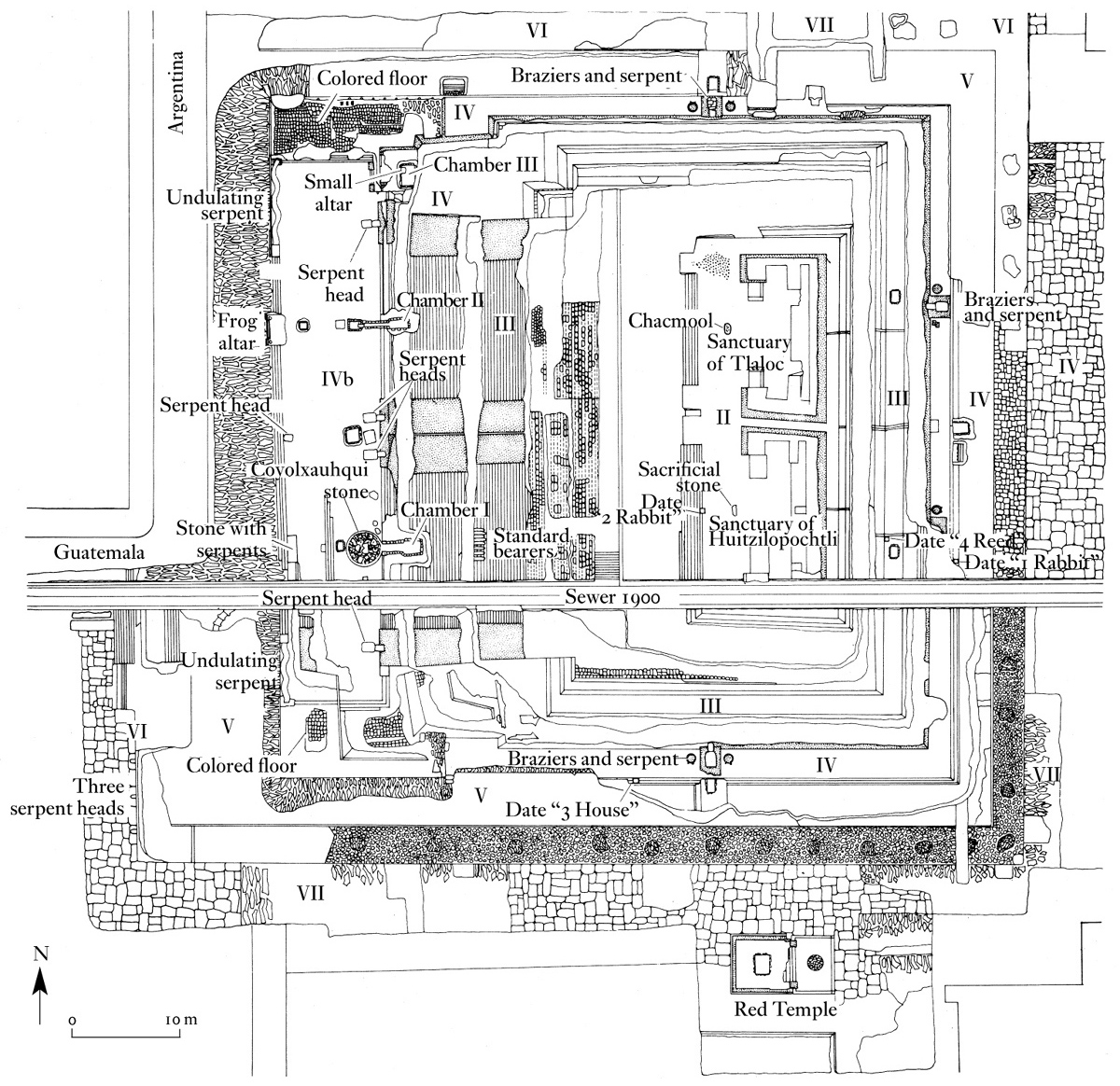

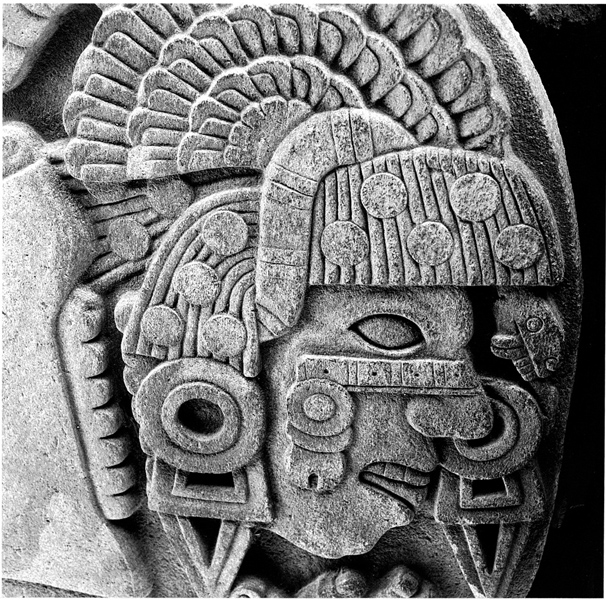

It has long been known that the ruins of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan (see ills 160–165) were located a short distance to the northeast of the Cathedral, underneath the buildings of Colonial and modern-day Mexico City. The chance discovery in 1978 of a huge oval monument by workers digging a pit for the installation of power transformers led to one of the most important Aztec archaeological discoveries of all time. This stone lies directly at the base of the Huitzilopochtli side of the temple, directly in front of one of seven successive rebuildings which the temple had undergone since its foundation. It bears on its upper surface a deep relief of the dismembered body of the goddess Coyolxauhqui, the malevolent sister of Huitzilopochtli, and is one of the masterpieces of Aztec sculptural art.

To understand the significance of this monument, we must recount the legend which lies behind it. Huitzilopochtli, the terrible warrior god of the sun, was the miraculous result of the impregnation of his widowed mother, Coatlicue (“She of the Serpent Skirt”), by a ball of feathers as she was sweeping one day on Coatepec (“Serpent Mountain”), near Tula. Angered by what they perceived as her dishonor, her 400 sons (the stars of the southern sky), egged on by their sister Coyolxauhqui (almost certainly an avatar of the Moon), attempted to kill her. Huitzilopochtli emerged fully armed from Coatlicue’s womb, and slew his sister Coyolxauhqui, hurling her body down from the summit of Coatepec, then pursued and defeated his 400 brothers – surely an astral myth of the defeat by the sun of the moon and the stars.

The importance of the legend, and of its confirmation by the find of the oval monument, is that the Huitzilopochtli side of the Great Temple was known to the Aztecs as “Coatepec.” This suggests there was a representation of Coyolxauhqui in front of each successive Huitzilopochtli pyramid, and such seems to have been the case, since two earlier versions of the goddess were found in the right position in older renovations. Coyolxauhqui was only one of a number of particularly powerful female deities represented in monumental sculptures associated with the Templo Mayor.

160 Plan of the excavated foundations of the Great Temple, showing remains of the successive construction stages; the oldest is Stage II. The Coyolxauhqui Stone (ills. 163, 164) is associated with Stage IV. The conquistadores would have seen Stage VI.

THE GREAT TEMPLE of TENOCHTITLAN

161 Polychrome jars, stone masks, and other offerings found in Chamber III beneath Stage IVb of the Great Temple.

162 Gruesome depictions in stone of skulls on a tzompantli or skull rack, excavated in the Great Temple precinct.

163 Colossal stone relief of the dismembered goddess Coyolxauhqui, discovered at the foot of an early building of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. Aztec culture, Late Post-Classic period. Longest dimension 11 ft 2 in (3.4 m).

164 Detail of the Coyolxauhqui Stone, showing the severed head of the goddess; her cheek is marked with a golden bell.

165 Excavations in progress at the Great Temple site, looking northeast. The oldest remaining pyramid-platform (Stage II Temple) lies under the protective roof at right. The Coyolxauhqui Stone can be seen beneath the scaffolding near the center of the picture.

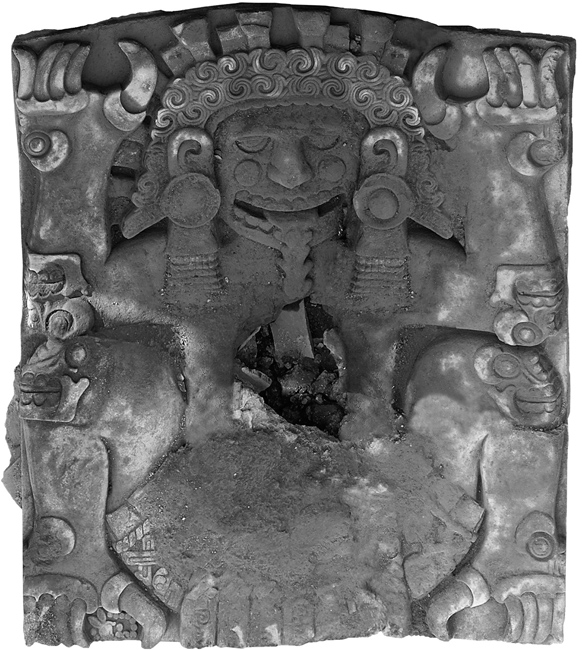

A spectacular relief of the goddess Tlaltecuhtli was recently found embedded in the plaza floor just to the west of the Coyolxauhqui monument and on the central axis of the pyramid (see ill. 166). The Tlaltecuhtli monument is even larger (c. 10 by 13 ft; 3 by 4 m) than the famous Sun Stone or the Coyolxauhqui monument. Because it was covered by yet another plaza floor within twenty years of its creation, it retains significant traces of the ocher, red, and blue paint that once decorated its entire surface. The top of the monument shows a grotesque head framed by claws. The hair is curly – a sign of ugliness for the Aztecs – and has paper banners emerging from the curls in a reference to sacrifice. Blood streams into the mouth from the now-destroyed abdomen area. The woven short skirt and the squatting pose at the base of the monument suggest that this is the female version of this voracious deity.

166 Monumental image of Tlaltecuhtli, the devouring earth goddess of the Aztecs. Archaeologists believe this colossal stone (c. 10 by 13 ft; 3.5 by 4 m), recently discovered near the Templo Mayor, may have covered a royal burial.

Tlaltecuhtli and related goddesses were also associated with earthquakes and thus the destruction of the current world era, a theme also evident in the Sun Stone, which was likely set up nearby. Cecilia Klein and Elizabeth Boone have recently reassessed several monumental female sculptures around the Templo Mayor, including the giant standing “Coatlicue,” and found that these are all associated with the tzitzimime – the mainly female star demons associated with childbirth, war, and ancestor contact, who were also responsible for devouring the population if the sun should fail. It is interesting to note, as Boone does, that these powerful stellar goddesses were shown decapitated here, perhaps signaling their defeat at the hands of the Aztec patron Huitzilopochtli, just as Coyolxauhqui was defeated and dismembered by that same god.

Immediately to the west of the Tlaltecuhtli monument, archaeologists found a stepped depression that led down to a spectacular series of dedicatory offerings. Approximately 15,000 items were buried in these deposits, including small-scale sculptures and many sacrificial animals. Much of the sea life found in this deposit was from the Pacific side of the Aztec empire, where the king Ahuitzotl (1486–1502) had his greatest military success. Archaeologists believe that it was Ahuitzotl who commissioned the Tlaltecuhtli monument: the associated offerings served to sacralize the area while pointing to Ahuitzotl’s military prowess.

Any discussion of the Templo Mayor owes a great deal to the remarkable archaeological work done there in the last several decades under Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Leonardo López Luján. From its earliest stages until the latest, the Great Temple was split between a right or south half, dedicated to the sun cult of Huitzilopochtli, and a left or north half devoted to the worship of the Rain God, Tlaloc. In the offering caches in the latter were found marvelous, blue-painted Tlaloc vases in both pottery and stone, along with shells, coral, and the like imported from the sea, while a dread sacrificial stone is still in place in the floor of an early stage of the Huitzilopochtli temple. The Great Temple was the conceptual center of the Aztec universe, so it is no surprise that this immense construction expressed the ancient duality implicit in all Aztec life: the contrast between rain and crop fertility, on the one hand, and war and the continued survival of the Fifth Sun, on the other.

The amount of surviving literature in the Nahuatl language is truly remarkable; written down in the letters of the European alphabet after the fall of the Aztec nation, these texts have given us a view into native philosophy that has no parallel elsewhere in the New World. The language used by Aztec poets and thinkers is richly metaphorical, making abundant use of double epithets, in which paired nouns have a third, inner meaning, thusly:

| Nahuatl | Translation | Meaning |

| Atl, tepetl | Water, mountain | City |

| Cuitlapilli, atlapilli | Tail, wing | The commoners |

| Petlatl, icpalli | Mat, seat | Rulership |

| Teoatl, tlachinolli | Divine water, blaze | War |

| Yollotli, eztli | Heart, blood | Cacao |

| Topco, petlacalco | In a box, in a coffer | Secretly |

| Teuhtli, tlazolli | Dust, filth | Evil, vice |

| Mixtitloan, ayautitlan | Out of the clouds, out of the mist | A wonder |

167 The Old World meets the New, AD 1519. Cortes and friendly nobles of the Tlaxcalan state. From the Lienzo de Tlaxcala.

References to supernaturals in the prayers and hymns are often shrouded in epithets, the divinity seldom being addressed by his or her true name. This was especially true of the awesome Tezcatlipoca, for whom were reserved such terms as “Lord of the Near, of the Nigh” (an epithet mistakenly applied by the early friars to the Christian God), “Night, Wind,” “The Enemy on Both Sides,” or “The Mocker.” To be able to narrate such discourse, and to understand it, was the mark of an educated person.

The most stylized of these texts were the Huehuetlatolli, the “Orations of the Elders”; these were didactic discourses directed to children in the calmecac and telpochcalli, as well as to adults, and were highly embellished with these literary devices. Book 6 of Sahagún’s encyclopedia of Aztec life presents these stock speeches in abundance, including the orations of parents to children, and orations delivered during pochteca banquets. From them, one may learn something of the mentality that enabled the Aztec people not only to survive misfortunes, disasters, and privations that would have broken others, but also to create one of the most advanced political states ever seen in Mexico. Raised in the sternest fashion in their homes and schools, trained to withstand cold and hunger, Aztec individuals embodied ideals which would have done credit to an “old Roman.” Self-restraint and humility were expected even of those whose fortunes soared, including the emperors themselves.

The mature man:

a heart as firm as stone,

a wise countenance,

the owner of a face, a heart,

capable of understanding.13

Not for them the megalomaniac self-esteem and lust for riches exhibited to the Aztec disgust by the Spaniards!

The image of the Aztec people as bloodthirsty savages bent only on rapine and murder – an image carefully fostered by the conquistadores – is belied by the great compendium of Nahuatl poetry preserved to us in the Cantares Mexicanos. Poetry was known as in xochitl, in cuicatl, “flowers, songs,” and was recited in the royal courts to the accompaniment of the teponaztli, a log slit-drum played with rubber-tipped drumsticks; the tones and beats of the drum are given in nonsense syllables for some poems, such as totocoto tototo cototo tiquititi titiqui tiquito. Although some of the compositions celebrate war and death on the “flowery field” (the battleground), through many of them there runs a singular streak of melancholy and pessimism, a philosophical theme particularly developed by the closely allied Texcocan royal house, known for its learning and cultivation. The transitoriness of life on this earth and the uncertainty of the hereafter appear in a song ascribed to the tlatoani Nezahualcoyotl, the poet-king of Texcoco:

I, Nezahualcoyotl, ask this:

Is it true one really lives on the earth?

Not forever on earth,

only a little while here.

Though it be jade it falls apart,

though it be gold it wears away

Not forever on earth,

only a little while here.14

To another poet, Tochihuitzin Coyolchiuhqui, life itself is an illusion:

Thus spoke Tochihuitzin,

thus spoke Coyolchiuhqui:

We only rise from sleep,

we only come to dream,

it is not true, it is not true,

that we come on earth to live.

As an herb in springtime,

so is our nature.

Our hearts give birth, make sprout,

the flowers of our flesh.

Some open their corollas,

then they become dry.

Thus spoke Tochihuitzin,

thus spoke Coyolchiuhqui.15

Yet finally Nezahualcoyotl came to the realization that “flowers, songs” never perish, and it is only through them that the truly wise man will approach the ultimate reality, the dual creator divinity in whom all things are contained, the Giver of Life. As an artist paints a book, so he has painted us with flowers and songs:

With flowers You paint,

O Giver of life!

With songs You give color,

with songs You shade

those who will live on the earth.

Later You will destroy eagles and jaguars:

we live only in Your painting

here, on the earth.

With black ink You will blot out

all that was friendship,

brotherhood, nobility.

You give shading

to those who will live on the earth.

We live only in Your book of paintings,

here on the earth.16