Parable of the Potter (18:1–19:15)

Potter’s house (18:2). The image of a potter’s house is a familiar one for Jeremiah. If we judge from the amount of pottery pieces lying all over archaeological sites in Israel, pottery was a well-known craft. In the ancient Near East, handmade pottery was crafted as early as 8500 B.C., which corresponds to the Neolithic period (ca. 9000–4300 B.C.).156 Pottery is a valuable instrument in helping archaeologists date historical events as well as archaeological discoveries. The kind of clay, the shape, decoration, kinds of handles, and colors are all used to develop a chronology and dating system.

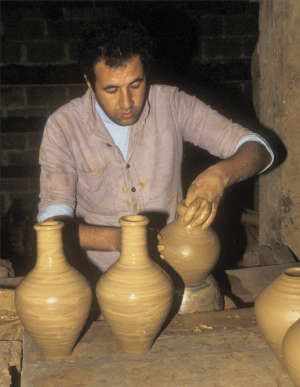

Potter at work on potter’s wheel

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

The potter’s house, or workshop, must have been a rather large place. It included various instruments as well as different areas of work. It had to have a potter’s wheel, a space for treading, a kiln, a field for storing vessels, and a dump for those pieces the potter discarded. The potter also needed a good source of water, which could either be a stream or a cistern nearby.157 An interesting potter’s house has been found in a tomb at Sakkarah, Egypt.158

The word for potter simply means “shaper.” This term is often used to describe God’s creative activity (Gen. 2:7–8; Ps. 94:9). The metaphor of a potter ascribed to the gods is also present in Mesopotamia. In the stories of Atrahasis, known as the Babylonian flood story, the god Nintu-Mami massages the uterus of the god Ea-Enki in the same way a potter shapes a clay vessel.159

Working at the wheel (18:3). The word for “wheel” here literally means “two stones.”

Model of potter at work

Kim Walton, courtesy of the Oriental Institute Museum

Excavations done at places such as Tel Miqne-Ekron have turned up seventh-century wheels made out of stone.160 The potter’s wheel has been in existence since approximately the fourth millennium B.C. In Jeremiah’s time there were two varieties, a slow wheel or tournette and a fast wheel. The one mentioned in this context is most likely the fast wheel model. This one consists of two disks or stones joined by a vertical axis. The lower one functions like a flywheel and is spun by the potter’s feet. In Sirach 38:29 we read, “So it is with the potter, sitting at his work, turning the wheel with his feet” (NEB). This causes the upper disk or stone to rotate as well. The clay is placed on the upper disk and is shaped by the hands of the potter. As explained in this parable, often during the process of “throwing” the clay, some defect appears either in the nature of the clay or in the design of the object. The potter then squeezes the developing object into a shapeless mass of clay and begins the process of creating the clay vessel over again.161

Virgin Israel (18:13). This title is used only two other times in Jeremiah (31:4, 21; cf. a modified form in 14:17). Outside of Jeremiah it appears only once more in the Prophets, in Amos 5:2. This term designates the entire people of God, and in this context it seems to be used in an ironic sense. The term “virgin” here most likely describes a young woman of marriageable age who is still under the legal supervision of her father. In Ugaritic texts, a cognate term is used as an epithet of the goddess Anat. In some texts she is referred to as the virgin warrior and the valiant widow.162 We cannot be sure exactly what this means, but it does not refer to virginity in the modern sense of the word, for according to the Ugaritic texts Anat has had sexual intercourse on more than one occasion.163

Snow of Lebanon (18:14). This phrase probably refers to the range of high mountains in the anti-Lebanon range. Many of these mountains are snowcapped most of the year. The highest mountain in Lebanon is called Qurnat as-Sawda, and the snow does not melt away on this mountain until late August.164

Snow-covered Mount Hermon

Almog/Wikimedia Commons

Roads not built up (18:15). Road construction in a more modern sense began during the Roman period. It was during that time that paved roads were built and marked by inscribed milestones. See sidebar on “Roads in the Ancient World.”

Dug a pit for me (18:20). “Pit” refers to the kind of pit used as a trap to catch animals. Many of these were dug in the desert in order to trap game. However, archaeological excavations show that pits were dug for other uses as well: storing pottery, burying garbage, and making temporary kinds of prisons. This term may be used in a figurative sense here.

Clay jar (19:1). The term for “jar” used here is baqbuq, which helps in identifying the kind of jar or earthenware jug referred to here. Most scholars agree that the jug Jeremiah buys is an expensive, ring-burnished decanter that functions as a carafe. It is from four to ten inches high and has a heavy body with a narrow neck. The handle is attached to the neck and rim.165 It is used for storing liquids, and its distinctive narrow neck emits a gurgling sound. The term baqbuq sounds much like that gurgling sound of liquid coming out of the jug.166 Here we have a symbolic action that is similar to the burial of the loincloth (see comments on 13:1).

Baqbuq-style jugs from Iron Age Jerusalem

Z. Radovan/www.BibleLandPictures.com

Valley of Ben Hinnom (19:2). This is one of the valleys that surround Jerusalem. It is located on the south side of the city and joins the Kidron Valley at the southeastern corner of the city (see also comments on 7:31).

Potsherd Gate (19:2). This gate is mentioned only here in Scripture; its exact location is unknown. It is presumably a gate that leads into the Ben Hinnom Valley. Some have suggested that it may be the same as the Dung Gate mentioned in Nehemiah 2:13; 3:13–14; 12:31. Since both dung and broken pottery were discarded into the Ben Hinnom Valley, this gate is a good candidate. In fact, both names of this gate are appropriate for the prophecy Jeremiah is about to give. Prophets in the ancient Near East occasionally accompanied their prophecies with a symbolic action that helped get the point across. In texts discovered at Mari there is a letter from governor Yaqqim-Adad of the city of Sagaratum sent to King Zimri-Lim (ca. 1775–1761 B.C.), in which he relates that a prophet has asked for a live lamb and then proceeded to tear it apart and eat its meat raw in public. This was done in order to announce that a pestilence would break out in the land.167

Burn their sons in the fire (19:5). See comments on 7:31.

I will make them eat the flesh of their sons and daughters (19:9). Both in Israel and in the ancient Near Eastern context, eating human flesh was only done under dire circumstances. Scripture testifies that in the cities of Samaria (2 Kings 6:26–29) and Jerusalem (Lam. 2:20; 4:10) during times of siege or famine, human flesh was eaten. Josephus writes that such atrocities also occurred during the Roman siege of Jerusalem.168 A similar curse to the one recorded here in Jeremiah can be found in the Vassal-Treaties of Esarhaddon, King of Assyria (681–669 B.C.): “May you eat in your hunger the flesh of your children, may through want and famine, one man eat the other’s flesh.”169

Just as this potter’s jar is smashed (19:11). The imagery here is one of destruction for the Israelites and their capital city, Jerusalem. This kind of image was common in the ancient Near East. In Egypt during the Middle Kingdom period (ca. 2106–1786 B.C.), the Egyptians practiced magical cursing against their present or potential enemies by inscribing pottery bowls with the names of their enemies and then smashing them.170 This served as poignant symbolic action, similar to Jeremiah’s actions here. In The Destruction of Sumer and Ur, the people who are defeated are described as being smashed as if they were clay potsherds.171

Smashed pottery

Manfred Näder, Gabana Studios, Germany

Burned incense on the roofs to all the starry hosts (19:13). The roofs of houses in the ancient Near East were flat and were used as living spaces. The roof served as a natural place to offer incense as an act of worship (see also 32:39; Zeph. 1:5). In 2 Kings 23:12 Josiah tears down altars that previous kings erected on the rooftops of houses.

There is further evidence of this from excavations carried out in 1992 at Ashkelon, which brought to light the results of the city’s destruction at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, in 604 B.C. Archaeologists have discovered remnants of incense burners that at one time were located on house roofs.172 In tablet III of the Assyrian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Ninsun (the mother of Gilgamesh) goes up to the roof to offer incense to the sun god, Shamash.173 This same practice seems to be alluded to in the Keret Epic from Ugarit, which probably comes from the thirteenth century B.C.174 (see comments on 6:20 and 8:2).