CHAPTER VIII

The Texan Santa Fe Expedition

The Santa Fe expedition has been the subject of comment and question; and while our standard histories have stated the main facts, forbearing judgment, we have found in some of the histories a few insinuations. For instance, one says, “The expedition was not only without authority of law, at the wrong season of the year without guides and provisions, but very expensive.” And another says, “The wild-goose campaign to Santa Fe was an ill-judged affair,” and so with other histories.

When the die is cast

And the deeds are done,

And all is past,

With no trophies won,

it is the rare and easy faculty of some people to make, as it were, post-mortem examinations, and sit in judgment upon the best efforts of some of our best men, generally deeming an enterprise ill-judged and wrong, if it be disastrous or unsuccessful. Views formed and expressed under such rule, however just, savor of ingratitude, and assertions should by all means be true with regard to design and effort, as well as the result. Men who were true and disinterested and ready to die for Texas suffered much and occasionally suffered defeat and persecution in lawful and laudable enterprises; this Santa Fe Expedition is a case in point.

John D. Morgan,1 an esteemed and reliable citizen of Bastrop County for many years, my associate and friend since boyhood, is the one man of our county who now lives to recall its scenes of danger and pain. I have lately taken from his life story a full account of this interesting campaign, its design and details, and record his entire experience throughout the siege as he now recalls it.

True, we are aged and gray. The years of exposure and hardship have brought pain and suffering to us in our old age. Those same years have wrought wonderful changes in the world around us, but the facts and habits of our younger days are fixed upon our hearts and memories, so that we love to think and talk of the joys when we were boys, of all the thrilling times which are gone like boyhood’s fun, and like the health and strength of young manhood.

The object of the expedition, as announced by President Lamar in his proclamation, was to get friendly intercourse with New Mexico and for protection through the intervening Indian country; it was thus deemed prudent to have military organization.

On or about the last of May, 1841, General Hugh McLeod, commanding about three hundred men,2 accompanied by one piece of artillery under Captain Lewis,3 started from Austin, being duly instructed to abstain, from all show of hostility.

First camp was at a Waco village, located where the city of Waco now stands, and here they rested a few days without interruption or adventure. Then the men went up the Brazos to the noted hill, known as Comanche Peak, where they crossed the river and went on to the three forks of the Trinity River. Here they had another few days of quiet rest and then traveled on for the Old Santa Fe Trail. So far everything went well, and it was both interesting and unusual for our men to pass through the temporary little farms cultivated by the Indians. Corn, pumpkins, and chickens were plentiful. Their villages were all vacated, however, as the savages fled at the approach of the army.

Now their troubles commenced. At first a few stragglers were surprised and killed by the Indians, and once they faced about two hundred warriors, well-mounted and armed with bows and arrows. But the artillery and firearms kept them at a respectful distance, though our men were in constant suspense and danger. Somewhere near the Wichita River their provisions gave out, and they had to depend upon their guns to get food. This was a very trivial matter, though, for buffalo, deer, and antelope were very plentiful; nevertheless, none felt safe on account of the Indians. Men would go out in full sight of the Indians to get food, and once our men were riding side to side with a band of Indians, all chasing the same herd of buffalo. But, at length, game could no longer be found, and as they kept up their steady march for the Santa Fe Trail, men began to suffer for food, meanwhile hunting diligently for game that was now so hard to find and yet so necessary.

Morgan was making his way back to the command after a day’s fruitless search for game—tired, hungry, and three or four miles from camp, when suddenly he came upon a soft-shelled turtle in the sand at his feet. Very happily he captured the reptile and carried it into camp. It was about one foot wide and made a rich supper for six of the hungry soldiers. It is a matter for curiosity to imagine how this creature came to be in that dry sand, miles from water. To the hungry men who were fast growing ravenous it seemed almost a gift direct from heaven.

At length, the jaded pack-horses were killed to satisfy the appetite of our men. About now, an intimate friend, by the name of Jones, was killed, which sad event brought a dark sorrow into camp and served to intensify the feelings of desperation that were fast taking hold of the stout hearts. Five or six dogs, which had followed their masters, were killed for meat; then came roasted terrapins, and once even a rattlesnake made supper for a starving few. Now prairie dogs became a delightful treat, as our men would occasionally find them in their eager quest for food. The pathetic look of disappointment on the face of one of the boys will ever be recalled with profound sympathy by those who saw it. Having carefully put a terrapin in the fire, he waited impatiently for it to get done. In a few minutes, coming to get his supper, lo! it had crawled off!

Three men were sent out in search of water, and on some stream in their wanderings were surprised and killed by Indians. Fifty men were detailed to find and bury their bodies, and a horrible scene greeted them, for brutal savages had cut their victims inhumanly, meanwhile using a common precaution of taking out their hearts. From all signs, the murdered men must have struggled manfully for their lives. Their horses had been killed and used as breastworks. In a few minutes the hungry men had some of this horseflesh on the fire. Alas! The men declare that in the torture of their long fast even human flesh looked tempting, and in the absence of these horses it is hard to say or imagine what might have happened at this burial of their butchered comrades!

A day or two further the command halted and after consultation agreed to separate. One hundred men under Captain Lewis, Colonel William Cook, Jose Antonio Navarro, and Dr. Richard Brenham struck out anew for Santa Fe.4 Now was the time of “extreme extremity,” for no sign of relief seemed near to the already sorely tried Texans. It is hard to place a limit upon human endurance, however, and the arduous march was prolonged ten or fifteen days longer, and they had absolutely nothing to eat during the last eight days of that period except an occasional jaded horse.

Levi Payne* and Morgan were messmates. Having drawn a pound or two of horse neck, they breakfasted on the same very economically, and put the balance into a haversack, with the agreement to separate and hunt for food individually. As it happened, Morgan carried the delicious (?) morsel of horse neck—the sole allowance of meat for two half-starved men until next morning. Dinner time found him “wearied, hungry, and almost tired of life,” alone on a high hill, two or three miles from the command. Power of sense or appetite conquered every other consideration, and as he rested he picked up the neck bone and struck out for camp, which he reached about dusk. He found himself unable to wait for Payne and began to pick on the skimpy morsel of horse. Meanwhile, Levi Payne had also hunted game in vain, and came in well nigh worn out. With considerable eagerness he said, “Well, Morgan, bring out our horse neck!”

“Why, Payne, I ate it all up!” was the trying answer.

This proved too much for the starving man, and to use Morgan’s own language, “He cursed me black and blue.”

In vain was all pleading or apology, as Morgan tried to tell him how hard he struggled to keep the meat, how hungry he became, but the words only increased his fury, and the little morsel of horse neck proved indeed a bone of contention, because poor Payne had none.

The company of men had nothing to eat that night, but next morning another horse was sacrificed, which was soon devoured; indeed, it was gone, and they looked only upon the bones and hoop, with hunger still half-satisfied.

Once more they were on the march; soon they fell in with a few Mexicans, who afterward proved to be spies, though our men were ignorant of their true character and intention. One of these was hired to act as courier, and was sent back to McLeod with a dispatch that they were within four days’ march of Santa Fe. Morgan was mounted on one of the best animals, a good mule, and this was demanded for the Mexican courier, to which he very reluctantly consented.

After a few days they struck a Mexican settlement known as Anton Chico.5 The army presented a woebegone spectacle now, after a fast of eight days, meanwhile tugging along over rough roads and dry country. Their eyes were sunken and looked eager and cadaverous as they entered the little Mexican villa. Some sheep were immediately bought from the natives and again their long hunger was partially appeased. How the tired and starved soldiers would eat! Six men ate a sheep and a half for supper that night. Next morning they succeeded in procuring some molasses and a little meal. This was at first considered a great treat, but afterwards proved to be poisoned, or at least so it was supposed, for whoever ate of it soon grew black in the face and suffered intense agony.

Thus our men were once more freed to hunger and wait. The waiting was brief, however, for suddenly they found themselves surrounded by a mixed army of Mexicans and Indians, numbering five or six hundred, who took possession of the horses and all the official papers sealed from Lamar to the government of New Mexico. At the same time Captain Lewis appeared upon the scene. He had been captured by Mexicans a few days before, and came with an order from the Governor of New Mexico to the effect that our men must give up all arms before they would be allowed to enter Santa Fe. This command produced much dissatisfaction and uneasiness, but after a little parley among the officers and privates, it was deemed prudent and best to obey.

Reinforcements from Indians and Mexicans were coming in almost hourly, and our men felt that the situation was growing more serious and desperate. As soon as the muskets were surrendered, all small arms, such as pocket pistols, bowie knives, and the like, were demanded. Again, after a vain and uneasy council, submission seemed not only best, but necessary, for the Texans were already helpless in the face of such odds. So every weapon of defense was delivered up, and now they were indeed at the mercy of the dark and motley army surrounding them, who at once proceeded to take advantage of their power.

They formed the prisoners in line in front of them. Then with guns presented, they tied eight of the men together with hands behind them. Still starving and thirsty they were marched into a house, where, through a terrible night of suspense and suffering, they were closely guarded by Mexicans.

Early next morning, without breakfast, they were led forth once more and backed against a stone wall, while Mexicans stood in double file in front of them, at a distance of about ten steps. Bill Allsbury,6 understanding their language well, suddenly called out, “Boys, they are going to shoot us!”

The scene was one beyond the reach of language or imagination and is recalled today with a shudder by the veteran soldiers who passed through its horror. Every cry and tone of agony, all kinds of language, curses, prayers, pleadings for food and for life—all were mingled and arose in one great heart-rending wail, as the tantalized Texans heard and saw the sure approach of so terrible a doom.

Suddenly a noise from a hill on the right attracted the attention of the enemy, and in another instant they perceived a reinforcement of four or five hundred troops approaching. Allsbury, still acting as interpreter, said they had decided to await the arrival of these before executing their cruel and murderous purpose. Still, however, they stood with guns presented. After an hour’s consultation they concluded to carry the prisoners to Mexico City. Still tied they were confined in the house, but a small beef was killed, upon which they were allowed a light meal. In the afternoon they marched under guard for Mexico City.

In a few days they came to what is known as “Dead Man’s March,” a sandy portion of the country about one hundred miles long and entirely destitute of water—a desert. Partial preparations to carry along water were made before entering upon this dry march. This supply, carried on oxcarts, in canteens, and in gourds was used with great economy, but gave out when water was still twenty miles distant.

Now suffering grew intense as the sore-footed and hungry prisoners were hurried along, every energy bent to make all possible speed to water. The Mexican guards showed no mercy toward some of the Texans who fainted by the wayside, but with a reckless cruelty shot them as they fell. Perhaps it saved the poor fellows a death of slow torture, but had they been left in peace they might have revived and struggled on to water, as did their comrades.

Nevertheless, it was not long before suffering made all equal, and the guards, impelled by the one fierce longing for water, ceased their vigilance and trudged onward, leaving behind them the weak and famished Texas boys, who labored forward until the line of march was at least a mile in length.

When within a mile of water the Mexicans began to meet them with canteens and gourds full of the precious beverage. From there the Texans would get a sip—only a sip—and then it would be all gone.

Of course this was the best thing to do for men in such famished condition, but it seemed indeed tantalizing to the men, whose tongues were swollen thick and so dry that it was hard to speak. Ever and anon, though, the welcome runners would meet them with portions of cold water. At last, just ahead a beautiful sheet of water spread out before their glad eyes; here was another scene almost pathetic enough for tears, as our Texans waded into the stream and drank.

Thence they were marched to the town of Chihuahua, en route for El Paso, and there they were simply paraded without relief and housed with strict guarding; then on in a monotonous treadmill of pain to El Paso. In that town they received kindness and mercy at the hands of the natives. They ate the first bread that they had had since leaving Austin, and feasted on grapes, pears, wines, and other good things. Ah, good indeed to the half-dead soldiers, who were permitted to enjoy a few days’ rest, gathering lost strength and vitality among this people who knew so well how to be kind and warm-hearted in their homes, but were always so brutal in war.

From El Paso they went on to Corretto, where they were again well-fed but were housed in small, close quarters, almost suffocating. Then on without adventure to the City of Mexico, where they were confined and put to work on the canal surrounding the city.

At length, Santa Anna (per secretary) gave a discharge, or pass, to each of the sorely tried Santa Fe prisoners, advising them to go home and henceforth be loyal to the royal government of Mexico.

That paper Mr. Morgan still holds—an interesting relic of this unfortunate campaign. Mr. Morgan lent us the original document and we handled the old relic with a careful interest, not unmixed with curiosity. A little slip of paper, yellow and stained by time, but as we examined it our minds bridged the intervening years and in imagination we recalled the homeless, battered men, destitute of everything, in an enemy’s country. How they must have rejoiced in the possession of this token of their liberty.

The Spanish reads thus:

Tejanos! La generoza nacion mejicana, a la que habeis ofendido en recompensa de un les de beneficios, os perdona. A su nombre siempre du gusto os restituyo lo libertad que perdisteis invadiendo nuestro territorio y violando nuestros hogares domesticos.

Marchad a los vuestros a publicar que el pueblo mejicano es tan generoso con los rendidos como valiente en los compos de batalla, probasties su valor probad absora su magnanimdad.

Mejico, junio 13, 1842

Antonio Lopez de

Santa Anna

The following is a free translation of the above:

Texans! The generous Mexican nation against which you have offended, as a reward to one of your number for benefits conferred, pardons you. In his name, which I love, I restore to you the liberty that you lost, while invading our territory, and violating our domestic firesides.

Go home and publish that the Mexican nation is as generous with the conquered, as it is valiant on the field of battle. You have proved their courage; prove now their magnanimity.

Mexico, June 13, 1842

Antonio Lopez de

Santa Anna

Ah, yes! Texas did bitterly prove and could in truth publish “the courage and magnanimity of Mexico” toward our soldiers. Time may in the coming years partially obliterate the memory of their persecutions; and future generations may come to regard all this as only

An ancient tale of wrong—

Like a tale of little meaning,

Though the words be strong.

As long, however, as a veteran of those trying times survives he can but remember and recount the thrilling scenes of suffering and persecution—no small part of the price paid for the independence and prosperity of our Lone Star State. And though the old soldiers, retired to the quiet of their homes, may sometimes feel themselves forgotten and unknown, yet every loyal heart will grow warm in reverence, gratitude, and love at sight or mention of the faithful veterans of Texas, whose frames grow feebler with the passing months, and whose ears are now listening for “the roll of the muffled drum.” God grant that when the summons comes they may have a passport from the Great Commander, which will ensure them a safe trip “through the valley of the shadow of death” into that home where they will ever more be free and happy.

The import of the pass is very characteristic of the war customs of the Mexicans in those times. See the complacent boast, “You have proved our courage!” Courage! Yes, courage or something else was required to overwhelm and imprison a small company of troops traversing their country on peaceful errand intent, and to persecute them to the limit of human endurance. And thus, no matter how brutal and ignoble a part they played in the scenes, they always publish themselves brave, victorious, and kind.

But back to our Santa Fe prisoners, who are free once more. As was ever the case, they found friends among the Mexican women. They were well-fed one day and furnished whiskey and tobacco enough to last them five or six days. And now they started out for home, passing through Puebla, Perote Jalapo, and on to Vera Cruz without adventure.

Here yellow fever caused much suffering among the already feeble men. Some died, whose names Morgan cannot now recall. From Vera Cruz on to Galveston, via schooner, and thence to Houston, which was then quite a small place. Here the little band scattered. Morgan, with two others, struck out for Bastrop County. Hatless, shoeless, and almost shirtless, they trudged homeward, finding along the road kind friends who gave them a warm and cordial welcome after their long exile. At last, footsore and tired, they found themselves at Sam Alexander’s,7 ten miles below Rutersville, where they found work. One month of rest and work at Alexander’s. Ah, the luxury of good beds, wholesome fare, and healthy employment in a friendly land!

Quiet was seldom vouchsafed our people then, however, and their season of enjoyment was of short duration. Almost immediately all Texas was aroused and indignant. General Woll took San Antonio, and men rushed to the rescue.

Morgan was once again on the march. Without gun or ammunition he started afoot for the Texas army, ere long overtaking and joining Eastland’s company. It was hard marching on foot, but he soon got to ride some by kindly exchange, and they camped at Peach Creek, where the widow McClure lived. That kind and patriotic woman, hearing of his need, furnished him her best riding horse, having already given ten or twelve horses to the Texas soldiers. If memory is not treacherous, she afterward became the wife of General Henry McCulloch.

Pressing on they came to the scene of Dawson’s massacre, which we have already described. Here Morgan recognized among the slain the body of Jerome B. Alexander,8 son of old Sam Alexander. They soon overtook other Texas troops, among whom were Captain “Paint” Caldwell and others of the old Santa Fe sufferers. A short rest, and then all went onward in pursuit of the Mexicans, whom they overtook on the Hondo River. Here our army formed a line of battle, expecting to fight, but the Mexicans retreated. Our troops camped for the night, sending out scouts, who returned and reported the enemy still retreating. The army was jaded, and turning back, camped at San Antonio, and disbanding, the next morning found them all homeward bound.

Morgan regrets that he did not get to see Mrs. McClure and thank her for the horse, which he left on passing her home, but he has ever remembered the kindness with great gratitude. The Texas women, God bless them, were soldiers, too, in those days. In due course of time we anticipate gleaning from some of them reminiscences no less interesting than those of the old men.

Morgan left Mrs. McClure’s horse at her home at Peach Creek, and plodded on foot back to Sam Alexander’s, but in a few weeks another call for men came. Captain Eastland insisted on having Morgan go with his men, although he was destitute of horse, gun, and the necessities. J. C. Calhoun,* formerly of Bastrop, agreed to furnish and equip him, and once more he marched with Eastland’s men for Mexico.

In a few days the Texas army assembled at La Grange, where they received from the ladies the flag of the Lone Star. She who presented it urged them in a few fitting words to be brave and loyal to Texas. The scene impressed itself upon the memory of the soldiers. The subsequent fate of the flag may be given in brief here. At Mier it was riddled with bullets, and when the Texans found they could no longer save it they burned it, preferring anything to seeing it fall into alien hands.

From La Grange they went to San Antonio, and there, after a short time in camp, General Somervell, with his army of five hundred men, marched for Mier.

We have already followed William Clopton through the trying scenes of the Mier Expedition, and will not repeat anything concerning the movements of the main army, except as Morgan’s experiences require.

They were on the Rio Grande, a few miles from Laredo, trying to crawl or creep up to the little town, expecting to find Mexican troops. As they rested a while on their horses, late one evening, Morgan, overcome with hard and continuous service, fell asleep with his bridle in his hand. He lost himself entirely, and supposes he must have slept an hour or more. Great was his surprise and dismay when he awoke and found himself alone. The army had gone! In the confusion and excitement no one of his comrades noticed or missed the worn-out soldier, who slept on, all unconscious of their movements and departure. Talk of the shifting scenes of life. Here indeed was a most bewildering change in one’s surroundings. To close the eyes upon an army, and after a little nap, to open them upon solitude, vast and complete. Rip Van Winkle himself was not more surprised and startled at the work of time, during his long sleep, and seldom do men find themselves at a greater loss. Alone, at dark, in a strange country, under a cloudy sky! He knew not how to turn, and studied in blank helplessness the darkness which enveloped him, listening in vain hope to hear some echo from the advancing army, but all in vain. Every moment of delay but lengthened the distance from his comrades, and finally he concluded to let his horse take his own course.

Brute instinct, as is sometimes the case, proved more trustworthy than human intelligence. Striking a long trot and neighing all the way, the animal soon bore him safely to the army. Surrounding Laredo about daybreak they found no Mexican troops, and the women of the little village arose and went about their household affairs, never dreaming that armed soldiers watched their movements. Angry and disappointed because there was no fight, the boys turned back for camp. Morgan and a comrade stopped at a private house for breakfast, which was cheerfully given by the Mexican woman, who seemed very much alarmed and distressed on account of the presence of Texas troops in their midst. They tried to quiet her fears by assuring her that Texas soldiers were too brave and honorable to disturb women and children.

Resting in camp a while after breakfast, the two men walked up in town again, and lo, the helpless place was sacked and robbed! That, too, by some of the “Texas soldiers.” Recognizing them, the women who gave them breakfast reminded them of their assurances of safety. Morgan says he turned away almost in tears to think of the exigencies of poor fallen humanity. The robbing of the town was entirely against orders.

Now on to a point near Mier. Morgan recalls the message of General Ampudia to our men: “If you want rations, come on! I have 4,000 men who will serve you with pleasure.” Three wild cheers and the Texans voted to go over.

William Clopton has already recounted the scenes of the struggle from his standpoint, so I will now pass on to the interesting details of Mr. Morgan’s individual experiences after the fight. He first carried his friend and neighbor, James Barber,9 into the hospital, the poor fellow being wounded in the breast. Then on his way to help others, he was arrested by one of the guards and required to stay with the wounded. He looked among the sufferers for Barber and hastened to his side. The poor fellow was breathing very hard and bleeding terribly from a bullet hole over the left nipple. Like that “soldier of the Legion,” who lay dying in Algiers, he knew he was almost dead, and sent a message to the loved ones at home, and gasped in death, “I die for Texas!” Surely, from that word of the dead and dying, on through these many years of growth and glory all Texas will thrill in memory of that simple sentence. Bend low, oh mighty Mother State, bend in tenderness, bend in love, bend in sorrowful pride, and catch from the clammy lips of the dying soldiers, the great devotion implied in, “I die for Texas!”

The next day the line was formed for Matamoros. Morgan was once more in the hands of the Mexicans. Now came hours of intense uneasiness for the old Santa Fe prisoners, who knew death was inevitable should they fall into the hands of their old persecutors and be recognized. Morgan says he watched and prayed for some chance to escape, but all in vain. At Matamoros, he and ten others who had charge of the sick and wounded were allowed the privilege of the town and suffered no great privation. In a few days, however, they were suddenly arrested and placed in a cell about ten feet square, with no light or anything of comfort or satisfaction. In here they contrived with a piece of an old pocket knife to get out two or three bricks and were working in patient hope to make their way out.

Late one evening the door was suddenly thrown open and the ten prisoners were rushed into the street to find themselves suddenly and completely surrounded. With a company of infantry on each side, cavalry on the outside, artillery before and behind, they were marched to Victoria. Later on they received an explanation of the sudden and strange proceedings, which was the story of the Texas prisoners rising on the guards at Saltillo. A march of eleven leagues that day after their close confinement left them very tired and low-spirited at night, with no possible chance for escape. From Victoria to Tampico suspense and despair filled their minds, for they felt that certain death awaited them at Mexico City.

Driven onward toward a cruel death, suffering meanwhile severe mental anguish and physical misery! Toil with hope may give one pleasure, but toil without hope or recompense must indeed be hard, especially when the physical powers have been taxed and tortured almost beyond endurance. Thus the little squad of ten Texans were driven along. At Tampico the natives were very kind and they were allowed some little liberty, but no possible escape. Thence, en route for the City of Mexico, they came to a little town, “Un Riel de Monte,” where there was a large silver mine worked by Englishmen. These offered to assist them if possible, but no opportunity was given and on they marched to the city of doom. Arriving there, however, Morgan was much relieved to find himself unrecognized as one of the old Santa Fe band. In a few days they were sent to a small town, Reno de Melone, and put to work on the roads, etc. Here he was recognized and much disturbed in mind by one Mexican, who was disagreeably inquisitive and showed himself by no means satisfied when Morgan evaded his questions, assuring him he was mistaken.

INDIANS. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

STORMING OF THE ALAMO. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

INDIAN HORSEMEN. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

SANTA ANNA1

FELIX HUSTON2

EDWARD BURLESON1

BEN MCCULLOCH2

SAM HIGHSMITH2

in Santa Anna’s uniform

R. M. WILLIAMSON1

JACK HAYS2

JOHN B. JONES2

CADDO CHIEF

PLACIDO, CHIEF OF THE TONKAWAS

KIOWA CHIEF

From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

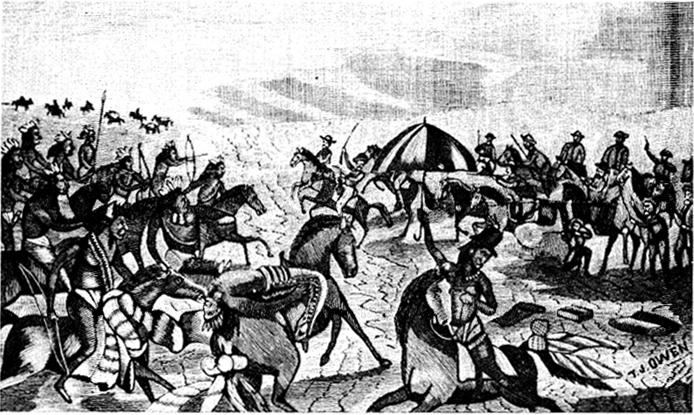

THE BATTLE OF PLUM CREEK. From J. W. Wilbarger, Indian Depredations in Texas, 1889

INDIAN WAR DANCE. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

COMANCHE WARRIOR. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

TRADING WITH THE INDIANS. From Homer S. Thrall, A Pictorial History of Texas, 1879

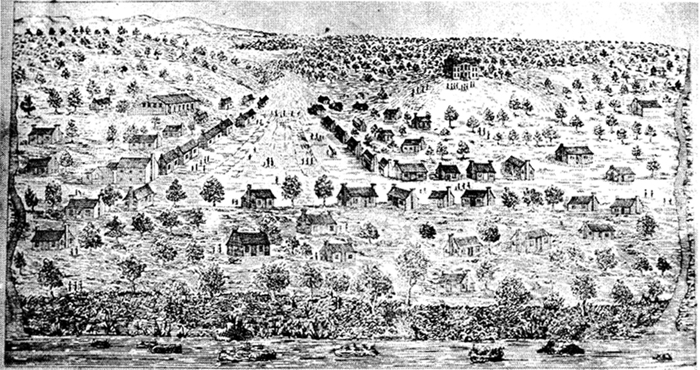

AUSTIN IN 1844. Courtesy Texas State Archives

TEXAS RANGERS, COMPANY D, at Realitas, Texas, in 1887

Back row from left: Jim King; Bass Outlaw; Riley Boston; Charles Fusselman; Mr. Durbin; Ernest Rogers; Chas. Barton; Walter Jones. Sitting: Bob Bell; Cal Aten; Capt. Frank Jones; Walter Durbin; Jim Robinson; Frank Schmidt. (Title and photo copyrighted by H. N. Rose.) Courtesy Ed Bartholomew, Frontier Pix, Houston, Texas

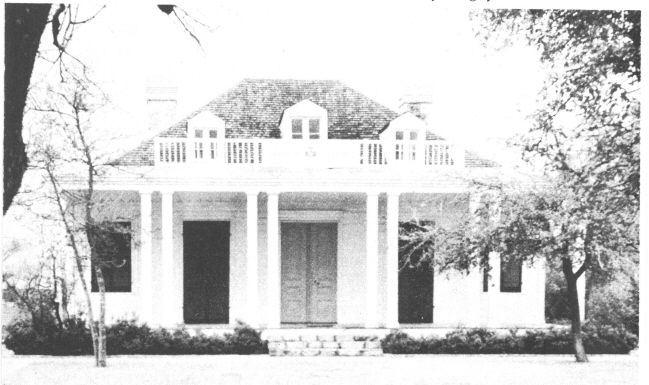

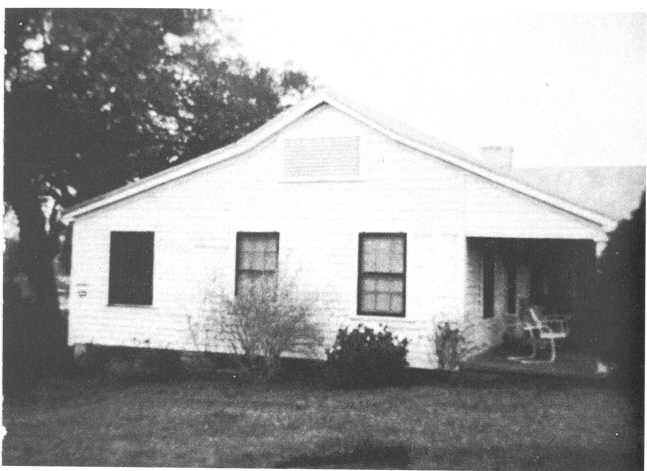

HOME OF A. WILEY HILL built on part of the old Jenkins league in 1854

THE FRENCH EMBASSY IN AUSTIN built by Saligny

HOME OF CAMPBELL TAYLOR built on the Old San Antonio Road in Bastrop about 1840

HOME OF COL. WASHINGTON JONES in Bastrop built about 1840

HOME OF JOHN HOLLAND JENKINS in Bastrop

JOHN TWOHIG RESIDENCE in San Antonio before the Civil War. Courtesy Ed Bartholomew, Frontier Pix, Houston, Texas

And now being recognized he felt that his worst fears were about to be realized and determined to make a last desperate effort for his freedom. He found a friend who promised to hide him if he could manage to get away. Morgan and three [?] others made the effort.10 They found two houses close together, not more than two feet apart and about ten feet high. Climbing this alley they found another height of ten feet confronted them and no way to climb—no foothold—nothing. They felt that “standing still is childish folly—going backward is a crime,” and soon proved that extreme difficulties vanish before undaunted and determined effort.

See the three men pause in the face of the new obstacle! See them look up at the height that must be reached, then around in vain effort to find some means to climb, and down into the street whence they have fled! What if the guards are already upon their heels! A happy thought comes to their aid. One of the number is tall, over six feet high, and a comrade is helped to his shoulder, on which he stands. From there he can reach the battlements of the roof, then up onto the roof. Here he fastens a rope up which they all climb. And now they are close to an aqueduct. Letting themselves into this they travel down it until they find a low place. Lowering themselves they are soon out. In eager haste they strike out as nearly as they can toward the friend who has promised to hide them.

The three fugitives soon came to a paper mill, where they were invited to take refreshments, after which they were guided two leagues further, where there was another paper mill belonging to an English company. There they were hidden for about three weeks, thus allowing time for the excitement to subside before again exposing themselves to the danger of arrest. Under cover of darkness they were taken in a carriage to the residence of the English minister, who knew all, but received them by asking, “Where were you shipwrecked?” The Texans stood in silent and puzzled confusion. Then laughing, he said with an oath, “I guess you were shipwrecked on high and dry land, were you not?” He was so generous and kind to the homeless men, that they felt for a little time almost safe, as they were “feasted and wined” under his protection two days, gathering lost strength and courage for their dangerous homeward trip. Then he “capped all” by presenting them with twenty dollars apiece, and had them driven in a carriage out of the City of Mexico after dark. Borne three leagues from this city of terror, they were put out on the road and directed to an English silver mine, still three leagues further on. And now farewell to safety and friends. They are again left to the suspense and danger of their trying situation.

They occasionally meet patrol-guards who question them with evident suspicion, but allow them to pass on when they claim that they are miners—as instructed by the English minister. Near daylight they grew very hungry, and ate at a wayside house, then on to the little mining town. Here they were hidden for three days, when they were appointed to guard a freight of silver destined for Vera Cruz. On to Perote, and here came the greatest trial of all, for here their comrades, the remnant of the Mier prisoners, were in bondage, and the three men were in constant danger of exposing themselves. Morgan, walking along with one of the guards, was strangely startled to hear him observe in passing, “We have a good many Texans confined here!” Of course, he had to ask why and wherefore, but it was somewhat akin to torture for him to quietly listen to a disinterested, cold account of the battle of Mier and its subsequent results. He says he waxed warm at the guard’s expressions of anger and condemnation toward the Texans, trying thereby to conceal the excitement and alarm of his situation. The guard wound up the history with, “Poor fellows! They fought manfully at Mier, and after all had to be brought here and put to work!”

“That is mild punishment,” Mr. Morgan remarked in reply. “They ought to be taken out and shot!”

Meanwhile, their fellow soldiers—that larger body of Mier prisoners—were toiling under insult and persecution almost in a stone’s-throw, and these three must hear unfeeling, barren facts, without the simple freedom of being honest and frank. Strange, to think of the power of circumstances! Soldiers with brave hearts, beating in wild, tumultuous rebellion at thought of the outrages upon their comrades—and yet they must seem only English miners, guarding their freight of silver.

They had been instructed to apply to the commander at Vera Cruz to secure his signature for their passport, and with much fear they went before him—two of them. They were kindly received, however, and their papers were fixed and they were soon in search of a conveyance. They were at supper, feeling relieved and to a certain extent safe, when a foreigner, coming in, made a special inquiry concerning “some Texans.” All were mum and busily engaged eating, as the landlord scanned the crowd about the table, and knew nothing about any Texans. As soon as possible, Morgan shoved his plate back, and retreated to the street, followed by the foreigner, who seemed never to dream that Morgan was one of the objects of his search. Morgan cooly inquired of him why he was seeking Texans. “I heard there were some in there, and I wanted to hire them,” he answered, but his manner was noncommunicative and evasive. He was doubtless in search of the three guards from the silver mine, our three escaped Texans, and did not know that he talked with one of them. Getting together after supper they “concluded to get out of there,” and were soon on board a schooner for New Orleans.

The Yankee skipper, who was commander, “found out their little pile” and charged the very last cent for passage, twenty-one dollars apiece! Few seem as anxious to let live as they are to live, and he was doubtless as happy in the possession of his sixty-three dollars as if our men had been well-supplied. Some souls are too narrow to separate, or to distinguish between the power and the right to do a thing. But we imagine life was not half so sweet to the captain of the schooner, as it was to three Texans, enjoying the rich delights of freedom for the first time in so long. Morgan is eloquent in memory of “the fair weather and pleasant trip,” and how they enjoyed it. At New Orleans, moneyless, friendless, and without clothes, they separated. The mate kindly gave Morgan supper at night, and now he found himself again alone, but this time “alone in a crowd.” After a day’s search on the wharf he found one schooner for Galveston, and proceeded to state his case to the captain, asking to be allowed to work his way. “No sail for two or three days, and my crew all made up,” was the discouraging answer. Now came a blank search for work.

In the midst of a busy crowd an idle man is uncomfortable enough, but a suffering, needy man, is most miserable. Like Tantalus of old, who needed most, watched the flow of water as it laughingly eddied past him, almost touching his dry lips, then receding, to leave him dying of thirst. At length, while a steamboat was being loaded, the captain turned and asked Morgan if he “didn’t want to work.”

“Yes, and I will be glad.”

“To work then.”

The work was too heavy for the taxed prisoner, and in three hours he was perfectly exhausted. Receiving three bits (12-1/2 cents an hour) for his work, he wandered forth once more, now only hoping to find somewhere a friend, for his strength had failed him.

Wandering up and down the streets he met a Texas agent and once again submitted his forlorn condition. The man said it was utterly impossible for him to furnish the distressed man any relief, but said, “Meet me at the schooner in a few days and I’ll try.”

Arriving at the schooner according to appointment, he did try, and after some parley with the captain received for answer, “I am tired of taking loafers to Galveston, but go to the foremast and stay; we’ll see.”

Out in mid-river he was set to work “belaying”—untying and tightening ropes, and work of that sort. It was very trying to stand and work all night in his condition. In three days he landed at Galveston and again wandered out, a friendless stranger, alone and needy. At last he struck an old Santa Fe comrade keeping bar, who said he was “broke” and was working simply for his “grub,” but “Come around at lunch time and I’ll give you something to eat, anyhow.” After two days’ waiting and wandering and watching, a steamboat landed from Houston. He immediately went on board in hope of securing passage up the river. Luckily, the watchman of the boat was another old Santa Fe comrade, who kindly took him in his berth and as soon as they were under headway brought him a good supper. Ah! indeed, “A fellow feeling makes us wondrous kind.” The old Santa Fe and Mier soldiers learned the value of sympathy and kindness in their hard life among the Mexicans, and could not refuse help, when they thus met, after all the trials and outrages.

At daylight the boat landed at Houston and Morgan set out in search of friends, several of whom he found, all money-less and friendless like himself. Resting one day, he started afoot for Bastrop County. He was nursed tenderly as a sick child along the road, indeed nothing of interest now came except kindness, but to be treated with consideration and confidence seemed the crowning glory of his regained liberty.

Once more Morgan stopped at his home with Sam Alexander, among old friends. After a short rest he decided to come still further, and resting again a little while at “Aunt Lookie Barton’s,” he came on to Wylie Hill’s. Thence after another short rest he went to “Mother Barton’s.” She knew him afar off and came to meet him, her face aglow with all a mother’s love and fear as she asked eagerly, “John, where is Jim?”

He found it hard to tell her the sad truth and the scene of the dying soldier in the hospital at Mier seemed all to harrowing for the poor woman who had been watching so anxiously for her boy to come home.

And now we quote Morgan’s closing word, “so ends a trying experience through which I have been safely brought by a kind Providence.”