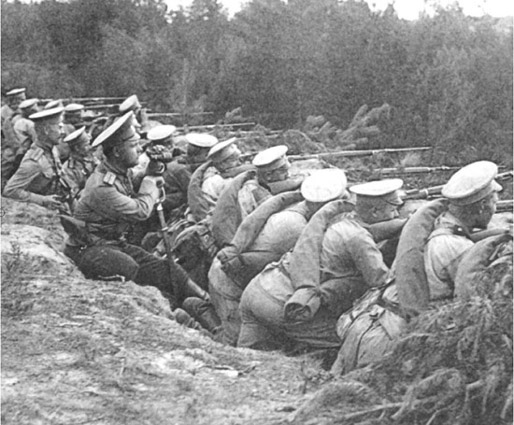

Russian infantrymen form a skirmish line early in the war. Russian officers were generally unimpressed with the quality of Russian soldiers, most of whom had little enthusiasm for the war and little identification with pan-Slavism.

Russian leaders supported their country’s entry into World War I, hoping to recover their nation’s power and prestige in the Balkans. The first battles went much better than many Russians expected, especially against the Austro-Hungarians. But the Russian Army soon suffered massive twin defeats that underscored the fundamental weaknesses of the Russian system.

When war broke out in the first days of August, seven of Germany’s eight field armies headed west on their ill-fated attempt to knock France out of the war in six weeks. While the Germans moved through Belgium and into France as part of the Schlieffen Plan, the forces of Austria-Hungary began mobilization aimed at meeting the wide variety of threats the war presented to them. Conrad had designed a war plan that divided his army into three components: one to deal with Serbia, one to move into southern Poland to hold off the Russians and one in reserve that could go north or south depending on the events in the war’s opening phases. While the plan looked good on paper, it overloaded the Austro-Hungarian transportation and communications systems, and soon proved to be an unmanageable tangle. Many units had to march for days to get to their assigned train stations only to find that there were no available trains to take them to the front. Conrad also wanted to be careful about which ethnic groups he sent where. Thus many of the forces to fight the Serbs came from far-flung (but not Slavic) parts of the empire like Bohemia.

All of Germany and Austria-Hungary’s planning counted on the Russians mobilizing very slowly. Only a presumption of Russian ineptitude would have dared to allow Conrad to send the majority of his forces elsewhere. As the Germans, under Helmuth von Moltke, gambled on a quick defeat of France, so, too, did Conrad gamble on being able to eliminate Serbia quickly without significant Russian interference. Only 20 Austrian divisions went into Poland to guard against Russian movements. Both Moltke and Conrad had assumed that capturing the enemy capital would give them the victory they sought, thus enabling forces to be redirected in plenty of time to meet the Russians. Both men were to be seriously disappointed.

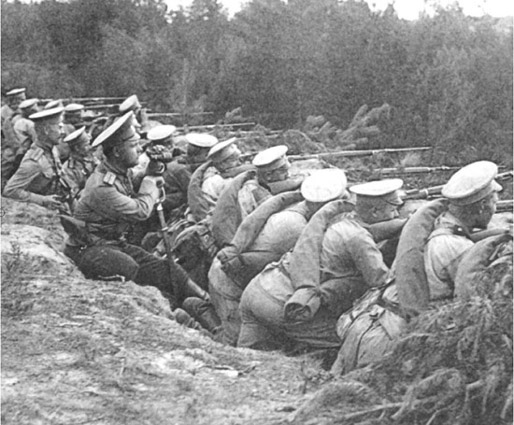

The large Polish Salient offered both opportunities and challenges to the Russians. They feared a joint German and Austro-Hungarian pincer attack on the salient, but also understood the advantages of assembling forces inside it.

Russia threw a giant spanner into all of the planning by Germany and Austria-Hungary, now known collectively with the Ottoman Empire as the Central Powers. In the first place, the Russian people met the Tsar’s call for mobilization on 30 July with an enthusiasm that few expected. This enthusiasm was mostly limited to young men in the growing Russian cities, but even so, thousands of young men joined the army and urban reservists reported to their units without much trouble. The Tsar made impassioned speeches to his people calling on all Russians to unite in a time of national crisis. Even in the countryside, peasants seemed to accept the necessity of the war, although they exhibited much less enthusiasm than the urbanites of Moscow and St Petersburg. The new Russian railways also came into play, as men and supplies moved from the hinterland of Russia to its mobilization centres with reasonable speed and efficiency. The Russians were still far behind the speed and efficiency of the Germans or the French, but all observers noted how much better the mobilization went than many Russians had feared.

‘The three Governments agree that when terms of peace come to be discussed, no one of the Allies will demand terms of peace without the previous agreement of each of the other Allies.’

Triple Entente declaration, 4 September 1914

Grand Duke Nikolai, the Tsar’s uncle, did not want the job of commander-in-chief. He believed he was ill suited to the task, despite a generally high reputation among Russian officers. He only accepted the position out of loyalty to his nephew the Tsar.

The key to the Russian mobilization plan lay in the central idea of a staged mobilization. Essentially, Russian planners had concluded that the immensity of their army and the size of Russia itself made it unwise to mobilize all resources first then deploy to the field. Doing so would simply overwhelm the rail network and the training camps at mobilization centres. Under the new plan, units would deploy into the field as soon as they were ready to do so. In a small country, such a plan would have risked placing too few men in the field to resist a determined enemy invasion. For the Russians, however, it meant that tens of thousands of men came into the field every week. The first divisions to be ready could go onto the offensive, while the second and third waves stood by to reinforce success, or, in a worst-case scenario, provide the required troops for a defence of the Russian homeland.

If the Central Powers had indeed coordinated their strategy and launched a joint invasion of Russia, it is unlikely that this mobilization scheme would have been equal to the task of defending Russia. The Russians had a badly exposed bump in their line known as the Polish Salient that the Germans and Austro-Hungarians could have hit simultaneously from the north and the south. But no such operation materialized as the Germans headed west and the Austro-Hungarians headed south, giving the Russians some much-needed space and time in which to. mobilize and deploy. It is entirely possible that the Russians knew the general outline of Central Powers planning: the Austro-Hungarian plans were likely slipped to them by Colonel Redl, their spy in the General Staff, and German intentions might well have been known from their French ally, who had divined the general outline of the Schlieffen Plan.

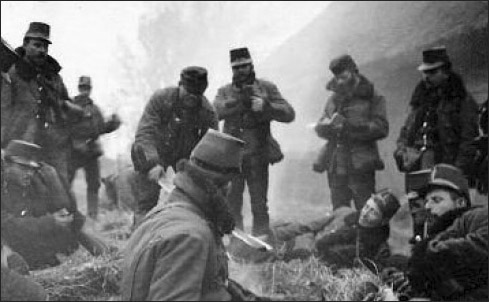

Austro-Hungarian soldiers, like these men, spoke a dizzying array of languages and came from dozens of often mutually antagonistic ethnic groups. This diversity imposed a special burden on the Austro-Hungarian mobilization process.

RUSSIAN WAR PLANS

What to do with the men that the Russians mobilized posed a different problem. The Russians had long assumed the need to fight both Germany and Austria-Hungary in the event of war, but the distances involved created tremendous challenges for Russian planners. The distance from Moscow to Berlin was 1860km (1156 miles) and the distance between Berlin and Vienna was 678km (421 miles), much too far away for a single campaign to encompass both enemy capitals. The terrain of Eastern Europe also posed challenges, as it possessed few railways and was generally lacking in the kinds of supplies an army needed on the march. Supply and logistics would present insurmountable challenges for a Russian general staff not well known for such skills.

In 1910, General Yuri Danilov proposed a solution to this dilemma. He discarded previous Russian war planning that had been based on the Napoleonic experience of withdrawing deep into Russian territory, sacrificing men and land and forcing the enemy to advance over poor terrain. Trading space for time had worked a century earlier, but Danilov thought the 1812 experience not worth repeating. Perhaps more importantly, he understood that times had changed and that a massive withdrawal into the Russian interior might have catastrophic consequences for Russian morale and the security of the Tsarist regime. He also knew that Russian and French generals had based their planning around coordinated offensive action against Germany to place pressure on the Germans from both the west and the east simultaneously. Russia would therefore need to throw away outmoded ways of thinking and develop an offensive war plan.

His solution became known as Plan 19, after the 19 army corps that he hoped to have ready to lead the first wave. Danilov had assumed that the Germans would attack France first, thus leaving East Prussia vulnerable. Two Russian armies would thus advance into East Prussia, a highly developed province that could provide food and fuel to an invading army. One of the Russian armies would then head toward Berlin while the other moved into mineral-rich Silesia. In the early phases of the war, the remaining Russian units would stay on the defensive around Russia’s outdated but still useful fortifications to repel any Austro-Hungarian attacks from the southwest. Once a sufficient number of units had mobilized in Ukraine, the Russian Army could also begin an offensive against Austria-Hungary along the Carpathian Mountains.

Residents in St Petersburg demonstrate in favour of the war during a brief display of national unity. The notoriously anti-Semitic Tsar even reached out to Russia’s Jews in 1914, but the mood of cooperation did not last.

The first Balkan War saw Serbia and its allies, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro, capture the Ottoman provinces of Novibazar and Macedonia in 1912. The war pushed the Ottomans in Europe back to the Gallipoli Peninsula and a small bridgehead protecting the western approaches of Constantinople itself. The Russians looked on favourably and offered the Balkan League its support, but did not engage directly. In 1912–13 the Second Balkan War broke out among the members of the Balkan League for their share of the spoils. The wars were a complete humiliation for the Ottoman Empire and a moment of great triumph for a resurgent Serbia.

The unexpectedly rapid Russian mobilization gave Russian commanders the resources to launch two attacks at the same time. Within 15 days after the declaration of mobilization on 30 July, the Russians had 27 divisions ready for combat. A week later, another 25 divisions were ready for combat. In all there were 90 Russian divisions in Europe and 20 more divisions in the Caucasus theatre by 1 September. The Russian high command thus decided to launch the attack on East Prussia, but abandon the essentially defensive part of the plan in favour of immediate operations against Austria-Hungary’s belt of Carpathian fortifications that guarded the mountain passes into the agricultural heartland of the empire in northern Hungary.

As a result, Russia was prepared to send enormous forces against Germany and Austria-Hungary simultaneously while the Germans and Austro-Hungarians were looking the other way. If these forces had been intelligently led they might have done some serious damage. The Russian officer corps was, however, rife with personal and professional rivalries that made efficient command and control virtually impossible. Two mutually suspicious cliques had developed, one based around modernizers in the War Ministry, the other based around more traditional ideas in the army’s general staff. The rivalries had grown so intense that many senior Russian officers were barely on speaking terms with one another and many more had diametrically opposed views on the nature of war. It had become policy in Russia to deal with this rivalry by assigning officers from both cliques to the same headquarters staffs in an effort to force them to overcome their differences, but this approach had largely failed, instead reinforcing the rivalries and jealousies.

Given the factionalism and rivalries in the army, Nicholas II looked to find an overall commander who might be able to rise above the fray. Even as the armies were deploying into the field, he changed senior leadership, asking his uncle, the distinguished military veteran Grand Duke Nikolai, to assume command. Nikolai reluctantly agreed to his nephew’s request. Although widely respected for championing reform in the Russian Army, Nikolai had been out of the mainstream of Russian military thinking since 1909 and had only heard faint inklings of the details of Plan 19. Thus the first task of the new Russian commander was to find out exactly what his own army’s plans were. He soon discovered to his dismay that the army had made wholly inadequate preparations for communications in the field and that important logistical details had been ignored altogether. It was not an auspicious start for the new commander of the largest army in Europe.

RENNENKAMPF AND SAMSONOV

Nikolai knew that the primitive state of Russian communications would pose tremendous problems to any effort at centralized command and control. Almost all messages sent from his office to the front went first to Warsaw, where they were decoded then sent forward to army and corps commanders by messenger. This cumbersome system was designed in part to compensate for the simple codes the Russians used. Changing code books across a vast and expansive Russian empire proved to be so daunting a task that the Russians tended to rely on older codes, which greatly increased the chance of their being broken. Sending messages overland by courier was a distinctly nineteenth-century way of doing business, but it significantly reduced the chances that the Germans would intercept a message and either decode it or gain another clue into how to break the Russian code system.

This image of a Russian soldier disguises the poor quality of equipment that most new recruits received. The large but inefficient Russian industrial and transportation systems had difficulties keeping men supplied throughout the war.

The initial Russian success in mobilizing much faster than the Germans had anticipated allowed two Russian armies to threaten East Prussia, the traditional seat of the Prussian elite. The commander of the German Eighth Army therefore decided on a massive retreat.

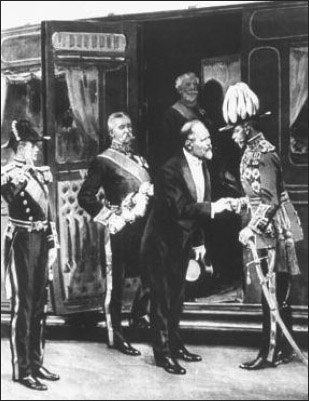

French President Raymond Poincaré meets King George V in a symbolic act of unity. Along with the Russians, the French and British determined not to seek a separate peace with Germany. Russia’s defeats, however, gave their allies concerns.

As a result of the Russian communications problems, command and control became unusually decentralized. While Moltke tried (with mixed results) to command the German Army from a field headquarters in Luxembourg and the French commander Joseph Joffre was able to monitor events and issue orders from his splendid headquarters in the Château de Chantilly near Paris, Nikolai could do little more than send his field commanders to the front and hope for the best. The quality of those commanders and the coordination between them would play a key role in determining the success or failure of the Russian armies in the field.

The invasion of East Prussia fell to the Russian First and Second armies, whose commanders were on opposite sides of almost every one of the rivalries and factions of the Russian Army. The First Army commander was Pavel Rennenkampf, a member of a Baltic German family who had risen quickly through the ranks of the Russian Army. Like many of his fellow Baltic Germans, Rennenkampf saw absolutely no contradiction between his German ancestry and his loyalty to the Russian state. He had fought in the Boxer Rebellion in China and had proved to be especially ruthless in 1905 in taking back two towns on the Trans-Siberian Railway from revolutionaries. For that act, the Tsar had singled him out for future promotion despite reports that he had mishandled his forces in combat in the Russo-Japanese War.

Several of the reports criticizing Rennenkampf’s conduct in the war had come from Alexander Samsonov, who commanded the Russian Second Army. Rennenkampf had never forgiven Samsonov for his intense criticism, both in the field and in reports to the Tsar and the army general staff after the war. A well travelled and often-repeated story of the two men getting into a fist fight on the railway station in Mukden during the war had been greatly exaggerated, but there was no exaggeration of the intense hostility between the two men. Unlike Rennenkampf, whose connections were in the general staff (called the Stavka), Samsonov’s links were in the War Ministry. Samsonov had been serving as governor of the far-away province of Turkestan when he was brought west to command the Second Army. The time apart had not made the two Russian commanders any more inclined to forgive and forget.

Together the two field armies were constituted as the Northwest Front (or army group) under the command of Yakov Zhilinski. A former military governor of Warsaw and then chief of staff of the Russian Army, Zhilinksi was probably the Russian officer who was most familiar with the plans of their French allies. He believed strongly in the need to attack Germany with as much force as possible as early as possible in accordance with the general outline of the Franco-Russian strategic talks he had supervised before the war. He was extremely unpopular for his dictatorial methods but he had an intimate understanding of the Russian Army and its general strategic outlook.

The command and control system of the Russian invasion of East Prussia thus could hardly have been less suited to modern war. The commander-in-chief, Grand Duke Nikolai, the Northwest Front commander, Zhilinksi, and both army commanders were all new to their posts. The two army commanders were not on speaking terms, and the front commander was disliked by both. Orders from the Stavka went by telegraph from Moscow to Warsaw then to Zhilinski’s field headquarters by courier and then to the army headquarters, if they could be located. Acknowledgement of receipt of the order had to follow the same path in reverse.

In all of the belligerent countries, the war led to an outpouring of patriotic sentiment. In Russia, the famously anti-Semitic Tsar even arranged to meet with prominent Jews as a sign of domestic unity. Political parties put aside much of their internal bickering and, in both Russia and Germany, parliaments ceded much of their authority to the executive. In Germany, the Kaiser initiated a policy of Burgfriede, or civil truce, between factions. He famously told his people that ‘I no longer recognize parties. I only recognize Germans’. These truces lasted until 1917, when the pressures of war began to erode them.

As if the personal rivalries were not serious enough, the Russians also faced immense challenges of geography. In between the First and Second armies sat the 97km-long (60-mile) Augustowo Forest and the 145km-long (90-mile) chain of lakes known as the Masurian Lakes. Any major offensive operation against East Prussia would force the First Army to go north of these barriers and the Second Army to go south of them. As a result their routes of march would become dangerously divergent and they would be in no position to offer mutual support to one another until they had advanced more than 240km (150 miles) and moved far to the west of the lakes. Given that speed and suppleness of manoeuvre were not the Russians’ strong suit, and given that the two armies would for all intents and purposes not be able to maintain secure communications between them, the task was daunting in the extreme.

Still, given that the bulk of the German Army was in Belgium and France, the Russian offensive at first experienced little resistance. Knowing that he was badly outnumbered, the commander of the only German army in the east, a friend of the Kaiser named Maximillien von Prittwitz, had decided on 20 August to move west more than 160km (100 miles) and draw the Russians into East Prussia. Once inside Germany, he knew that the Russians would be unable to use the German railway network, which used a different gauge from the Russian.

General Pavel Rennenkampf was descended from Baltic Germans and earned a reputation for ferocity during the 1905 Revolution. His slow-footed performance in 1914 led to dismissal from the army and a court inquiry.

Prittwitz also knew that his subordinate commanders would be fighting on terrain they had trained on for years and would thus be in a much better position to round up and defeat isolated Russian units, even if those units were larger, by surrounding them and cutting them off from their lines of supply.

THE BATTLE OF GUMBINNEN

Prittwitz was just about ready to order the final phase of the withdrawal when the Russian communication problems changed the picture dramatically. German I Corps intelligence officers had picked up a local message from Rennenkampf to his division commanders that had been broadcast, en clair (meaning without the use of codes), over radio waves. The message ordered a halt in movement on 20 August just south of the border town of Gumbinnen to give his men a rest and to allow supplies to be brought forward. The order went to I Corps commander, General Hermann von François, an aggressive officer with more than the usual German hatred of Slavs. He was already aghast at Prittwitz’s proposal to withdraw and voluntarily cede parts of Germany to the Russian invaders and had subsequently disobeyed his orders and moved his units east, not west. François informed Prittwitz that he was going to attack the Russians at Gumbinnen instead of falling back. Prittwitz had his doubts, but gave his impatient subordinate permission to proceed.

The Russian invasion of East Prussia led to a critical command change in the German Eighth Army. The cautious Max von Prittwitz was dismissed and the new team of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff was sent east.

To make sure that the attack had every chance of success, Prittwitz ordered two of his corps to join François at Gumbinnen, leaving his fourth corps in reserve. François recklessly pressed ahead without waiting for the other two corps to complete their preparations. He attacked the much larger Russian forces at 4am on 20 August, achieving surprise and pushing Russian forces back as far as eight kilometres (five miles). François thought that he had scored a major victory and urged the other two German corps to come forward and complete the annihilation of the Russian First Army.

General Alexander Samsonov confidently led his forces into East Prussia, unaware that the Germans were preparing to spring a trap on him. His subsequent massive defeat at Tannenberg led him to commit suicide rather than face the consequences back in Russia.

The two corps arrived on the battlefield piecemeal, with one arriving at 8am and the other only arriving at midday. François had in fact only fought against a weak advance guard; as the Germans forced their way east they came up against the main body of First Army, including its artillery. The three German corps fought separately against powerful (if inefficiently employed) Russian forces. Seeing how badly they were outnumbered and outgunned, the German XVII Corps began a withdrawal at the end of the day. The other two corps, including François’s I Corps, had little choice but to follow suit, leaving more than 6000 German prisoners in Russian hands.

Prittwitz panicked. His units were in disarray and he expected Rennenkampf to pursue with the utmost vigour. He also had no clear idea of where Samsonov’s Second Army was. He therefore feared that he might be encircled and destroyed by much larger Russian forces. He designed an even more ambitious retreat, proposing to retire behind the Vistula River to buy time, even if such a withdrawal essentially meant abandoning all of East Prussia to the Russians. Prittwitz informed Moltke of his new plan, but his commander’s reaction was not what he had expected. Directing the attack on Paris from his headquarters in Luxembourg, Moltke went into a rage and ordered the withdrawal stopped immediately. He also informed Prittwitz that he and his chief of staff were being removed from command, leading to Prittwitz’s retirement. The defence of East Prussia would fall to the hands of new commanders with new ideas.

THE BATTLE OF TANNENBERG

Prittwitz’s replacement was Paul von Hindenburg, who quickly forgot all about his apple trees and sped to the train station at Hanover. The imposing general had been retired for three years, but he had lost none of his professional demeanour or his ability to sum up a military problem quickly. After spending his retirement thinking about a Russian invasion of East Prussia, he was now in the position to do something about it. Moltke knew that Hindenburg would bring a steady hand to the Eighth Army and that he would not panic as Prittwitz had. He also knew that Hindenburg would command respect from loose cannons like his corps commander François.

At Hanover train station, Hindenburg met his new chief of staff for the first time, General Erich Ludendorff. Ludendorff had become one of Germany’s first heroes of the war by designing and executing the German capture of the powerful Belgian fortifications at Liège. Ludendorff had pounded on the door of the town’s citadel with the hilt of his sword demanding the surrender, making a name for himself in Germany and earning the trust and respect of Moltke and the Kaiser. Ludendorff was unpopular and unpleasant as a colleague and a superior, but he was also a hard worker and a reliable administrator who could turn Hindenburg’s strategic vision into operations.

German infantry, with their distinctive helmets covered, advance as part of the Tannenberg campaign. The swift decision making of the German Eighth Army commanders allowed German forces to encircle and cut off their Russian foes with minimal losses.

On the train from Hanover to their new command, the two men discussed their options and the intelligence reports from the field. According to those reports, Rennenkampf had shown little desire to move his units forwards after his success at Gumbinnen despite the fact that just one German cavalry division sat opposite him. Ludendorff concluded that although the Russian First Army had been victorious at Gumbinnen it had obviously suffered badly enough to make it cautious. He guessed that if it had not moved forwards immediately to exploit its success, then it was likely planning to stay where it was to receive reinforcements and supplies.

By the time they reached East Prussia, Hindenburg and Ludendorff had realized that the most enticing opportunity lay in concentrating against Samsonov’s Second Army. With Rennenkampf paralyzed, and highly unlikely to risk his tired army by coming to the aid of his arch-nemesis, the Second Army was ripe for the picking. Thus although it had been beaten at Gumbinnen, the German Eighth Army would not retreat to the Vistula, but would instead resume the offensive by falling on both flanks of the Russian Second Army, with the ultimate goal of turning it in against itself, cutting it off from all hope of rescue and supply and forcing it to fight to its death or surrender.

On arrival at their new headquarters, Hindenburg and Ludendorff discovered that the Eighth Army operations officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Max Hoffmann, had already come to the same general conclusions. He had prepared orders for his new superiors’ approval to move François’s I Corps by rail to the town of Seeben, where it would be on Samsonov’s left flank without the Russians’ knowledge. Two more corps would move by foot, with XX Corps moving directly opposite the Russians to hold them in place while XVII Corps would close the trap from the north and fall on Samsonov’s right wing. The one solitary cavalry division would remain opposite Rennenkampf’s First Army to screen it and keep a close eye on its movements.

The German commanders did not see their plan as a gamble, nor did they worry about the setback at Gumbinnen. They were in very comfortable intellectual territory in designing what the Germans called a Kesselschlacht, or killing cauldron. Such a daring manoeuvre had been taught to generations of German officers as the best way for a smaller army to defeat a larger one by more rapid movement, the attainment of surprise, and attacks on two flanks simultaneously. The model was the great Battle of Cannae in 216 BC where Hannibal had encircled and annihilated a much more powerful force of Roman legions. Indeed, the idea was so familiar to officers trained in the German staff system that three officers who had never worked together before, independently saw it as the obvious solution to the problem in front of them.

Their beliefs were confirmed by two more en clair Russian messages that the Germans intercepted. The first was from Rennenkampf’s staff to Samsonov’s informing them that the Russian First Army would move slowly towards the northwest. The message confirmed that the two Russian armies would continue to march in diverging directions and that Rennenkampf would be in no position to come to Samsonov’s assistance even if he felt inclined to do so. The second message was in response to the first, with Samsonov’s staff giving Rennenkampf’s staff (and, unwittingly, the Germans as well) their anticipated lines of march for the next two days. An elated Hoffmann rushed both messages to Hindenburg and Ludendorff. The latter was so amazed at the Russian sloppiness that he dismissed the messages as a crude Russian deception operation. Hoffmann told him of similar messages the Germans had already intercepted and convinced Ludendorff of their authenticity. Messages found on a dead Russian officer provided more evidence to overcome Ludendorff’s scepticism.

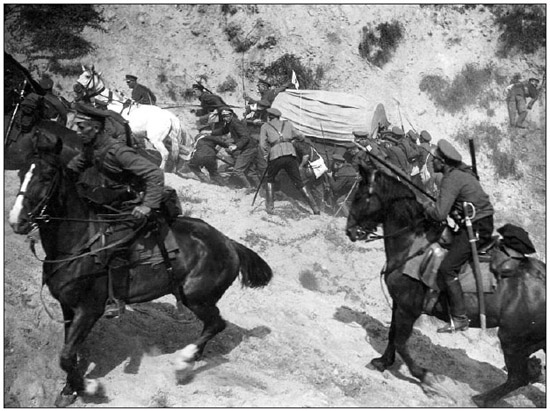

In the more open spaces of the Eastern Front cavalry could still play its traditional reconnaissance role. It could also still be used to pursue retreating enemy soldiers and cut off lines of retreat.

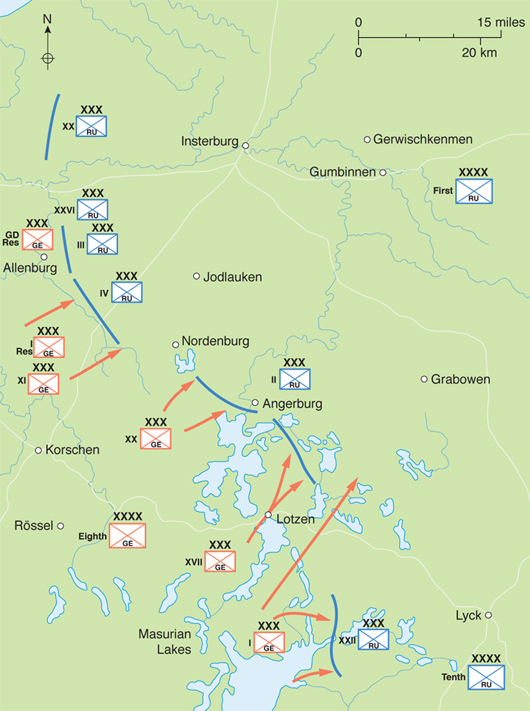

The Germans used just one cavalry division to screen the Russian First Army while the remainder of the German Eighth Army moved south to surround the Russian Second Army. German forces were therefore able to encircle the Russians and destroy them.

Samsonov never saw what hit him on 27 August, just a week after the Russian victory at Gumbinnen. Zhilinski had informed him of the First Army’s triumph and advised him not to expect significant German forces to be in his sector, as they would likely begin a retreat. He therefore told Samsonov that he could advance in a leisurely manner. Unworried about any German resistance, Samsonov moved his centre corps forward, leaving its flanks dangerously exposed to any possible assault.

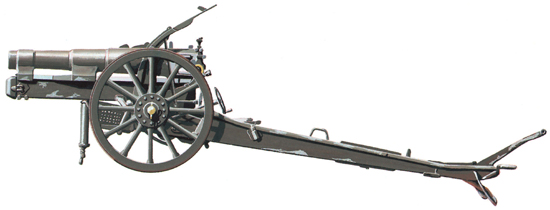

German field artillery crossing a river in full flow on the Eastern Front. The German 77mm field gun was designed to advance with the infantry and provide fire support on the move. It was the German equivalent of the famous French 75mm field gun.

Taking advantage of the Russian slackness, the Germans responded with rapid movements aimed at encircling the Russian Second Army before Samsonov could even divine the size of the German forces opposite them. François, humbled just a bit after his bloody error of judgement at Gumbinnen, argued with Ludendorff for more time to properly prepare his artillery. Afraid of losing the critical element of surprise, Ludendorff urged action, and François finally complied. On 27 August, he stretched his I Corps to the south of the Russian left flank, and reached Soldau just inside the Russian border on Samsonov’s main route of supply. He then moved north and east, seizing key roads and making any Russian retreat from the battlefield all but impossible.

Rennenkampf faced charges of incompetence after his handling of the opening moves of the war. Although he had fought better than Samsonov, the latter was dead by his own hand and Rennenkampf became the easiest scapegoat. His German last name led to additional charges of treason, although these charges were unfounded. He faced a trial for mismanagement of public funds and only avoided prison through the grace of some of his well connected friends. He retired to a dacha on the Black Sea and in 1918 was approached by the Bolsheviks as a possible commander for the Red Army on the assumption of his hatred for the regime that had humiliated him. He refused the offer, whereupon the Bolsheviks accused him of treason and had him executed.

A German defensive position on the Eastern Front. German infantry were on the whole better trained, better equipped and better led than their Russian counterparts. After Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, German officers grew confident in their ability to beat the Russians.

Nervous and tense hours followed as the rest of the trap was sprung. By the morning hours of 28 August, the Germans had control of almost all of the main roads leading to Samsonov’s forces. Combat began in the north when a Russian corps, advancing without support, ran into a German corps. The Germans, who were fully aware of the Russian presence and were lying in wait for them, smashed the Russians and sent them reeling back in panic. Surprised at the unanticipated presence of German forces in the area, Samsonov ordered a general withdrawal that night. The full severity of the situation came slowly to him as he realized that he was completely cut off. His men began to panic, throwing down weapons and running east as fast they could, only to end up trapped by strong German forces already sitting on their lines of retreat.

Confusion and panic reigned in Russian lines. Without supplies and without communications, panic spread quickly. Rennenkampf’s forces were more than 113km (70 miles) away and would obviously not provide any help at all. On 29 August, Samsonov himself gave into the panic. He told a staff officer, ‘The Tsar trusted me. How can I face him after such a disaster?’ He then headed off into the woods, where he committed suicide rather than face capture by the Germans. He was one of the lucky ones. Samsonov’s powerful army of 150,000 men had suffered one of the most lopsided defeats in military history. More than 30,000 Russians were killed and almost 100,000 entered prisoner of war camps where they faced a dismal future of forced labour and appallingly bad conditions. The Germans needed 60 trains to move all of the Russian equipment they captured. German casualties were less than 20,000.

It was probably Max Hoffmann who first suggested calling the victory Tannenberg, in revenge for a nearby 1410 battle at which the Slavs had defeated the Teutonic Knights. He, Ludendorff and Hindenburg shared in the glory of the victory and later competed for their share, with Hoffmann especially claiming that the plan had been his all along. Zhilinksi soon lost his job as the man most responsible for the destruction of four Russian corps. To be sure, Russia still had 33 more corps in the field or ready to deploy, but Tannenberg had destroyed any hope that they might see an easy march to Berlin. It had also seemingly confirmed the superiority of German efficiency and methods over those of their hopelessly antiquated Russian foes.

THE BATTLE OF THE MASURIAN LAKES

With the Russian Second Army decisively defeated and German confidence soaring, the Eighth Army decided not to sit on its laurels. Even before Tannenberg, Moltke had decided to reinforce it, although initially the reinforcements were intended to provide extra men to defend East Prussia. These reinforcements included two corps that Moltke controversially removed from the right wing of the German First Army in Belgium, later leading to charges (most of them not supported by evidence) that if he had not removed them, the Germans might have been able to complete their victory in the west. After Tannenberg, Moltke continued to send new drafts of men to the east. By September, the Eighth Army had 18 infantry and three cavalry divisions. Plans were already in the works to add two new field armies in the east.

The Germans again tried to take advantage of poor Russian communications and slow Russian deployment. On news of the disaster at Tannenberg, Rennenkampf had sent part of his army south as a precaution, but the movement had been designed poorly. As a result, part of the Russian First Army was separated from the main force and therefore dangerously exposed to any rapid German concentrations. Once again, Russian headquarters contributed to the problem by misunderstanding German intentions. Stavka informed Rennenkampf that he had nothing immediate to worry about as the Germans were expected to head to the Warsaw area.

Russian cavalry had a long and proud tradition. Several of the Russian Army’s top commanders had been cavalrymen. The Russians used cavalry to screen and reconnoitre in the vast distances of the Eastern Front.

Instead, the Germans hurried north to try to do to Rennenkampf what they had just done to Samsonov. François marched his corps more than 113km (70 miles) in just four days, placing it on the southern flank of the detached part of Rennenkampf’s forces. François attacked the Russians on 7 September, forcing the detachment to retreat north to the presumed safety of the rest of the Russian First Army, and compelling Rennenkampf to change his deployment and route of march from the west to the south. Rennenkampf acted cautiously and methodically, and was understandably anxious to avoid putting himself in the kind of trap that had ensnared Samsonov. Still, he could not move too far to the north without running into the strong German forces at the fortress of Königsberg.

The culmination of the Battle of Tannenberg. The Russian Second Army, now encircled by the corps of the German Eighth Army, was largely destroyed, with losses of 130,000 out of its strength of 150,000 men.

Rennenkampf therefore decided to play it safe. He sent two divisions south to form a rearguard that would hold off the advancing Germans as long as possible while the rest of his divisions slipped the noose and headed east to the safety of the Russian border. On 9 September, the rearguard began its furious defence, trapping advancing German units in the forests and narrow lanes between lakes. At the same time, the Russians badly exposed themselves to German machine-gun and artillery fire by conducting furious and haphazard charges. Rennenkampf ‘s decision allowed most of the First Army to escape, but in three days of fighting, the Russians still lost an amazing 150,000 men and 150 artillery pieces. Most of the men in the two rearguard divisions ended up dead or prisoners of war.

Rennenkampf took few chances even with his withdrawal. He moved his men 80km (50 miles) to the east, evacuating East Prussia and giving it back to the Germans. Returning to Russia meant at least temporary safety because the Germans could not move men or supplies by rail until they had accumulated enough rolling stock on the Russian gauge. Finally, a piece of good luck helped the Russians when heavy rains started to fall in mid-September, turning the dirt roads into mud and slowing any German pursuit. The Russians needed time to regroup, replace their losses, and reassess their strategic approach to the war.

For their part, the Germans were disappointed at the lost chance to eliminate another Russian army, but they had done very well for themselves. Their losses had been much smaller than those of the Russians, but they came from much smaller armies and thus the Germans, too, needed to reinforce and resupply.

Nicknamed ‘The Devil’s Paint Brush’, the German Spandau machine gun, introduced in 1908, could fire 500 7.92mm rounds per minute. This model dates from 1915 when the cumbersome water jacket was replaced by this perforated air-cooled barrel.

Especially in light of German setbacks in the west at the Battle of the Marne, the victories in the east were welcome news for the Germans and suggested to many officers that the Germans might be better served to stay in trenches on the Western Front and repel French and British attacks while seeking to repeat the formula of Tannenberg in the east, thus knocking the Russians out of the war.

Thus began a grand strategic argument in German circles between ‘westerners’ and ‘easterners’. The former argued that deep operations into Russia were risky and extremely taxing on German logistical lines. They understood how deftly and efficiently the Germans had beaten the Russians not once, but twice. Still, they knew that the Russians had enormous reserves of manpower upon which they could call and looked aghast at repeating Napoleon’s mistake of chasing the Russians deep within their own territory. Instead, they called for a full effort to defeat France and Britain on the Western Front following the theory that the Russians would not be able to stay in the war without their allies. Victory in the west would give Germany most of what it had fought the war for, especially favourable trade terms and colonial concessions. The Germans would also be likely to be able to hold on to whatever lands in Poland and the Baltic region that they had taken.

‘I beg most humbly to report to Your Majesty that the ring round the larger part of the Russian Army was closed yesterday.’

Hindenburg’s message to the Kaiser on the Battle of Tannenberg

The Russian Army relied on the M1902 light field gun. It fired a 76.2mm shell at a maximum range of 6420m (7020 yards). Although the gun was adequate, Russian artillery techniques were not as advanced or as sophisticated as those in the German Army.

Easterners argued that the hopes for victory on the Western Front were slim. The German drive on Paris having failed, the two sides had begun to entrench and the war in France showed every sign of reaching a stalemate. In the east, on the other hand, the distances were too great for a system of entrenchments to be effective and the Germans had already shown a remarkable superiority to the Russian. Easterners called for strengthening the defensive lines in the west and attacking the Russians with full force. Once the Russians had been beaten, they argued, Germany could redirect troops to the west and have sufficient striking power to break the deadlock in France.

These discussions animated German officers in the autumn of 1914 and for a long time afterwards. The real question involved not just strategy, but logistics. German officials had to determine whether new troops and new weapons would go west to France or east to Russia. No German officer, whether a westerner or an easterner, wanted to see Germany become mired in a perpetual two-front war that most felt the Germans would eventually lose. Some way still had to be found to win the war quickly, although the debate continued as to where German resources might best be employed for years to come.

Safe for the time being behind their borders, the Russians soon recovered from their panic and took stock of their resources. They knew that they could replace the manpower losses of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, and they also knew that the French and British would help them replenish their lost artillery pieces. Reorganization of their forces was the first priority, with the Russians especially concerned about German intentions against the centre of the Polish Salient. They also hoped to use the units of the Southwest Front, which had not been involved in the battles of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, in a drive into Galicia against the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s armies.

Thus, while Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes might go down in the annals of German military history as unusually successful battles, they had not achieved the aim of taking one of Germany’s foes out of the war. On the contrary, the Russians were preparing an offensive of their own. The Russian reorganization removed many incompetent commanders and forced a fundamental rethinking of Russian strategy that promised to pay dividends. France and Britain, although stressed on their own front, extended financial credits to the Russians to help them pay for needed equipment and to give them the flexibility to call more men to the colours. Russia still showed signs of both great weakness and, despite its losses, great strength.

AUSTRIA-HUNGARY’S GALICIAN OFFENSIVE

While Germany’s war against the Russians had been a surprising success, Austria-Hungary had experienced calamitous failure almost from the start. Conrad’s elegant plans fell apart owing to the fragility of the Austro-Hungarian railway network and his astonishingly blithe dismissal of the threat posed by the Russians in his war planning. On the outbreak of hostilities, Conrad sent 200,000 men to invade Serbia.

The much different ‘force-to-space’ ratio on the Eastern Front made the digging of extensive trench systems much less efficient. War in the east was therefore more fluid than war in the west.

Although some parts of the Eastern Front featured intricate trench systems, the distances involved forbade the kinds of solid trench networks common in France and Belgium. War in the east therefore centred around communications hubs like highway crossings, forts and railway stations. As at Tannenberg, the side that moved faster and more deftly usually held the advantage. The much more effective German staff system gave Germany that advantage in almost all of its engagements with the Russians.

Constituted as Minimalgruppe Balkan, they were led, ominously enough, by the man who had been in charge of security for Franz Ferdinand’s fateful visit to Sarajevo. They were to enter Serbia simultaneously from the west and northwest and capture the Serbian capital of Belgrade.

But the Serbs proved to be a much tougher opponent than most Austro-Hungarians had supposed. Most of the soldiers in the Serbian Army were veterans of the two Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. They were therefore experienced and battle featured numerous mountains and rivers to which the Serbs had added an impressive ring of field fortifications. In mid-August, the Serbs drove the Austrians back even though they possessed few modern weapons and almost no heavy artillery. Convinced that they had proven their invincibility, the Serbs boldly invaded Austria-Hungary, hoping to be seen as liberating the Slavs of the hated empire and fomenting a pan-Slavic rebellion.

The Austro-Hungarian setbacks in Serbia produced important ripple effects throughout Eastern Europe. At the same time that his invasion of Serbia was falling apart, Conrad became aware of the full implications of Germany’s commitment to win the war in the west before turning east in force. He recognized the gravity of the situation immediately, as no large German forces coming east to deter the Russians meant that the Russians were free to concentrate in Poland and even in Galicia. Even those German forces that were in the east, the Eighth Army, went north to defend East Prussia instead of into the Polish Salient where they might have helped the Austro-Hungarian positions nearby. Thus, not even the two titanic German victories of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes provided much help to Conrad, as they were too far away from his own positions to impede or threaten the Russians moving toward him.

Even with the strength of the fortresses taken into consideration, this force was insufficient if the Russians arrived in force. This fear struck Conrad and his staff as the full weight of the situation became clear. The Austro-Hungarians could expect little to no help from their German allies for several months owing to the heavy commitments to France and, to a lesser extent, East Prussia (commitments for which Conrad never forgave them). The Austrian Second Army was all that was available to provide some extra help to A-Staffel, the main force consisting of four armies. It contained 10 divisions and was called BStaffel under the Austro-Hungarian war plan.

But B-Staffel faced problems of its own. Its units came from all over the empire and had to be concentrated and organized before Conrad could decide where they should go. The war plan called for that concentration to occur in Galicia in the north because the railway network was much more efficient there. Thus B-Staffel was organizing and forming near where it would be needed if Conrad decided that the Russians were the greater threat. When, however, the invasion of Serbia failed and the Serbs actually invaded Austria-Hungary, Conrad instead ordered BStaffel sent south. The chaos and confusion of war made it virtually impossible for B-Staffel to move south with any speed at all. As a result, it spent most of August organizing and trying to move first north then south then north again when the Russian threat appeared the more dangerous. It thus did not fight at all during the month.

Russian cavalry on the move early in the war. Their weapons were too light to allow them to engage large German formations, but they could be effective in limited missions such as reconnaissance.

Fortunately for the Austro-Hungarians, the Russians in the south mobilized more slowly than they had in north. They were commanded by Nikolai Ivanov, whose most compelling qualification for the job was a firm and unwavering belief in absolute monarchy as the only appropriate political system for Russia. He had brutally suppressed the Kronstadt naval mutiny in 1906 and been rewarded with command of the Kiev military district and the patronage of Nicholas II. Upon the outbreak of war he assumed command of the Southwestern Front (army group) of four armies comprising more than 400,000 men with thousands more on the way. Unsure of himself and terrified of making a mistake that would disappoint the Tsar, Ivanov missed a series of opportunities to deploy quickly and put pressure on Austria-Hungary while it was distracted by the Serbian campaign and the confusion created by its own mobilization plan.

Austrian soldiers at rest in the war’s early months. A confused war plan forced the Austro-Hungarian high command to move its men frenetically between fronts, creating a great deal of fatigue, especially among reservists.

Three of Ivanov’s four army commanders were equally as cautious as he was. General Alexei Evert, another officer with Baltic German origins, was given command of the Fourth Army at the last minute. Like Ivanov, he believed in being cautious and did not want to go on to the offensive until he knew his army better and every conceivable detail had been worked out to his satisfaction. He was so particular that many of his peers thought he was more interested in making excuses for his inaction than he was in defeating the Austro-Hungarians. To his left in command of the Fifth Army was Wenzel von Plehve, who was not a Baltic German, but a Prussian who had chosen service in the Russian Army as a young officer because he expected that he could rise faster and higher in the service of the Tsar than in the top-heavy army of the Kaiser. Serving in a foreign army for reasons of career advancement had been common before the twentieth century but ascendant nationalism had made it seem like treason. Plehve was therefore an unusual species of officer in 1914, but he remained loyal to the Tsar, although he much preferred fighting the Austro-Hungarians to his own Germans. He was reasonably competent, but was also seriously ill, probably with cancer.

The one exception to this list of mediocre Russian commanders was the Eighth Army commander, Alexei Brusilov. He was, ironically, vacationing in Germany when Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. He had originally seen no reason to hurry home, but when Austria-Hungary delivered its ultimatum to Serbia he sensed the danger and headed back to Russia. At the Berlin train station he saw crowds demanding war with Russia and knew that war was imminent. He rushed back to the Eighth Army and began to prepare it for the invasion of Galicia. He was one of the best trainers and planners to be found in any army in 1914 and had already developed innovative tactics for the new battlefield that he expected the killing power of machine guns to create.

Austrian soldiers firing light artillery rounds near the fortress of Lemberg. The fortress guarded one of the strategic passes in the Carpathian Mountains as well as a key rail junction. It was therefore an important lynchpin in Austrian strategy.

While the Russians dithered, Conrad decided that his best defence against the Russian Army would be an offensive to clear Galicia and secure the approaches to the mountain passes. On 23 August, he ordered the First Army to advance northeast in the direction of Lublin and the Fourth Army to advance on its right. Further to the southeast, the Third Army would advance due east from Lemberg. The B-Staffel was ordered to move (again), this time north to secure the right flank of this advance. Conrad was gratified to learn that the Germans had begun to form a new army, the Ninth, in the area north of Cracow that could help secure the offensive’s other flank.

At first, the operation showed signs of success. The First and Fourth armies, advancing northeast, pushed Evert’s Fourth Army and Plehve’s Fifth Army back, driving them almost 160km (100 miles). But the northeastward advance created a gap between the Fourth Army and the Third Army to its south, which was advancing due east. The Third Army ran into trouble when it reached a fortified Russian position known as the Gnila Lipa Line on 26 August. There, Brusilov’s Eighth Army and the adjacent Third Army sprang a trap and smashed in the flanks of the Austrian advance. Conrad responded by ordering the Fourth Army to change its route of march and move south to help out the beleaguered Third Army.

The Fourth Army’s commander, Moritz von Auffenberg, vigorously protested the order. With his forces driving the Russians back, he saw no reason to stop his attacks in order to reinforce the failure of the Third Army. He also argued that changing his route of march would dangerously expose his flanks to an attack from the Russian Third Army as well as creating a gap that would expose the Austro-Hungarian First Army. Conrad disagreed and reissued the orders to a furious Auffenberg.

Auffenberg’s fury was soon proved valid. The gaps between the Austro-Hungarian armies left them unable to come to one another’s aid. Anchoring their attacks around Brusilov’s success in the south, the Russians moved into those gaps, threatening the flanks and lines of communications of all three Austro-Hungarian armies. Auffenberg took little comfort from Conrad’s belated ability to see the situation for what it was and order a retreat. The Second and Third armies began a retreat that eventually covered more than 160km (100 miles) and put them up against the Carpathian Mountains, surrendering all of their gains and more. Auffenberg led part of his Fourth Army to the Carpathian foothills, barely escaping a Russian encirclement in the process. The rest of the Fourth Army was cut off from its intended line of retreat and had little choice but to head to the presumed safety of the fortress city of Lemberg. The city, however, was not ready to receive thousands of tired and bedraggled soldiers, creating a major drain on food, clothing and other critical supplies. The appearance of the defeated soldiers also lowered morale in the city, with disastrous consequences.

After destroying Samsonov’s Second Army at Tannenberg, the Germans turned on Rennenkampf’s First Army near the Masurian Lakes. Rennenkampf managed to get part of his army out of the trap, but still suffered a massive defeat.

Alexei Evert had a long and successful military record that included service in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877. He led inconsistently in 1914 but was nevertheless given command of an army. A supporter of the Romanovs, he died under mysterious circumstances in 1918.

Although Auffenberg had been right to question Conrad’s decision making in the campaign, Conrad succeeded in blaming him for his alleged failure to reach the Third Army in time to prevent the retreat from being necessary. Auffenberg lost his command and retired into obscurity. The Austro-Hungarian position became increasingly dire. The Russians could now advance unhindered towards the fortresses of Lemberg and Przemysl, which were the gateways to the Carpathian Mountain passes and the keys to unfettered use of the railways of Galicia. It only remained to be seen how quickly the Russians could organize and move. The first few weeks of the war had gone terribly for Conrad and the Austro-Hungarian Army, requiring them to plead for help from their German allies. That help would soon come, but at the price of Austro-Hungarian strategic and operational independence.

The Czech Skoda works provided the Austro-Hungarian artillery corps with some excellent weapons, including this 149mm Model 14 howitzer. Its great drawback was its weight, which made it difficult to move unless broken down into two pieces.