Russian field artillerists firing over ‘open sights’. The Russians were less experienced in sophisticated techniques such as indirect fire, wherein a spotter signalled the location of enemy targets to concealed artillerymen.

Although two entire Russian armies had been badly beaten by the Germans at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, other Russian armies enjoyed considerable success against the Austro-Hungarians along the Carpathian Mountains. These victories helped the Russians remain in the war and gave them confidence that they could still win a great victory.

The Austro-Hungarian retreat that followed the Russian victory in Galicia soon developed into a rout. Thousands of Austro-Hungarian soldiers, most of them ethnic Slavs, simply deserted from the army. Many of them walked to Russian lines hoping to exchange information for food. Some even switched sides to fight with their fellow Slavs in the Russian Army against the hated Austro-Hungarians. In late August, the Austro-Hungarians reassembled the few men still under their control and set up a line of defence east of the fortress of Lemberg. The demoralization of the troops, however, made the line weak and the Russians had little trouble closing in on it from several directions. Russian Eighth Army commander General Alexei Brusilov pushed his Russian soldiers hard from 26 to 30 August, arriving at the Austro-Hungarian line near Halicz before the Austro-Hungarians had been able to finish even rudimentary defensive preparations.

On 31 August, Brusilov attacked and routed the right wing of the Austro-Hungarian line. Russian troops conducted a spirited bayonet charge, terrifying the already wavering Austro-Hungarians. Casualty estimates for World War I, especially on the Eastern Front, are notoriously inaccurate, but contemporary figures put Austro-Hungarian losses at 5000 men and 32 artillery pieces, many of which had not even been put in position to fire. As a drenching rain turned roads to mire and further demoralized the Austro-Hungarians, they retreated again, this time to a semicircle running north and east of Lemberg. As Austro-Hungarian soldiers continued to desert en masse, gaps in the defensive lines appeared that they could not fill. For more than a week, the Russians put pressure on the line, slowly and steadily driving the Austro-Hungarians out of their field defences and into the fortresses outside Lemberg itself.

As August turned to September, panic began to spread inside Lemberg. There was plenty of food and ammunition to allow the Austro-Hungarians to offer a reasonable defence of the city and its fortifications, but the scene of so many bedraggled and defeated soldiers sent the city into a paroxysm of fear of what the oncoming Russians might do. Rumours of thousands of men fleeing from the army and gross incompetence in the officer corps added to the mood of fear. The town’s leaders undoubtedly knew that the main body of the Austro-Hungarian Army had moved well west, meaning that if the city did try to offer a sustained and prolonged resistance to the Russians, it could expect little immediate help. And as the city and army’s leaders must also have known, the customs of siege warfare dictated that the longer a city held out, the more vicious would be its sacking.

Amid this environment, the smashed remnants of five Austrian corps converged on a terrified Lemberg. Some Austro-Hungarian units had managed to recover and offer belated resistance, but it was far too little too late. The Russians began an artillery bombardment of the city and moved infantry around it to cut off possible avenues of retreat to the west. In the early morning hours of 2 September, Russian troops began to enter the city’s suburbs. The Austro-Hungarians sent the only troops at hand to meet the charge. They were part of one of the last remaining contingents of Slavs and the Russian commander ordered his men to fire above their heads as a signal that they could safely surrender themselves rather than be killed. The Slavs understood the message and threw down their guns and walked to Russian lines. Non-Slavic troops fled in the opposite direction. Most never made it out of the closing Russian noose

1. Troops from the side from which the Russians had to come faced the least favorable passes, and operated with the least shelter from biting winds.… Steep and craggy in their northern expanse, they fall away toward the south in broken, sloping plateaus. The passes vary in length from seven to 230 miles. Peaks rise to 8000 feet, the Gerlsdorfer, the highest, reaching 8737.

2. The Carpathians have no formations to compare with Alpine groups or our own Rockies, but there are innumerable peaks, which vary in altitude from 5000 to 8000 feet. Because of the involved character of the passes, they have been for ages effective barriers against invaders. Prolonged siege warfare is impossible in the Carpathians. Trenches could be used for the protection of particular positions, but there could be no continuous lines of trenches.

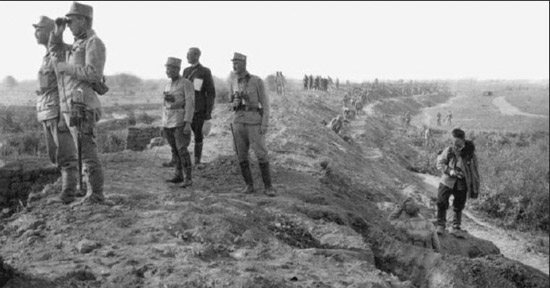

Austro-Hungarian officers survey a battlefield. Despite an official policy of encouraging diversity, the officer corps of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was disproportionately German in origin, and this bias grew more pronounced in the higher ranks.

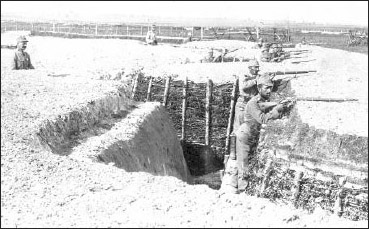

This image of elaborate Austrian field defences rarely matched the reality. Defences in the vastness of the Eastern Front more commonly centred around river crossings, railway junctures and other strategic locations which needed protecting from the enemy’s forces.

Russia achieved the first major Allied victory on any front by capturing the city on 3 September. The defeat of the Austro-Hungarian forces outside Lemberg had been so thorough that the Russians entered the city itself without firing a shot, an event that created a scandal inside Austria-Hungary. Reports that Slavic residents had welcomed the Russians as liberators also served as a bad omen for the possible future disintegration of the polyglot Austro-Hungarian Empire. The capture of Lemberg, which the Russians soon renamed the more Slavic-sounding Lvov, provided a critical morale boost not just to Russia, but to France and Britain as well. Estimates of the number of Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war stretch to 130,000, of whom perhaps 60,000 voluntarily deserted. Along with the prisoners came almost 700 artillery pieces, 2000 machine guns, 500,000 rifles (many of them from the city’s large arsenal), mountains of ammunition, tons of food and control of the region’s most important railway hub. More than eight rail lines converged at Lvov and the Russians soon took possession of captured rolling stock and the most important locomotive factory in Galicia as well.

The triumph at Lvov was soon followed by news of the important Franco-British victory on the Marne. Momentum seemed to be on Russia’s side, but by September 1914 the Russian drive into Galicia had stalled. As often happened on the Eastern Front, armies advanced much further than their lines of communication could supply them, and the reorganization of Lvov for Russian purposes would take some time. Fresh Austro-Hungarian units had managed to set up a new line of defence near Grodek, roughly halfway between Lvov and the next major Austrian-Hungarian fortress complex at Przemysl, 97km (60 miles) to the west. The Austro-Hungarian left was anchored on the San River, a barrier that the Russians, acting with their customary caution, did not want to test until they had taken the time to regroup and reorganize.

The Russians did, however, begin to move against the city of Jaroslav on the San. They appear to have only wanted to stretch their forces towards the river to prepare for a future crossing. Russian forces fired shells into the city as they approached it, sending residents there into a panic like the one that had gripped Lemberg. Upon seeing the Russians approach in force, Austro-Hungarian forces voluntarily withdrew from Jaroslav, thus surrendering the entire San River. Their withdrawal also forced them to abandon the critical railroad from Cracow to Przemysl. The Russians cut the line and took command of the northern approaches to the massive Austro-Hungarian fortress complex at Przemysl, less than 48km (30 miles) away. At the same time, Brusilov moved on Grodek, the last major town on the eastern side of Przemysl, taking it with few casualties on 12 September.

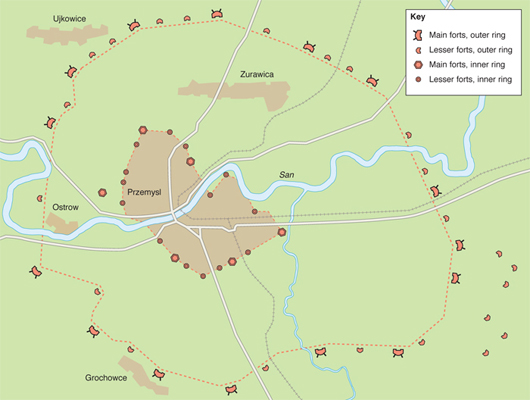

The Russian position now looked much more favourable for a major autumn campaign. They controlled two of the three main rail lines leading into Przemysl and had effectively severed the Austro-Hungarian Empire from the rich agricultural and mineral resources of Galicia. Control of Przemysl would allow them to approach the Carpathian Mountain passes into Hungary and their cavalry patrols had already ridden into the Dukla Pass and found it lightly guarded. Russian generals therefore turned their focus on Przemysl, whose fall would leave the road to Cracow (and beyond Cracow, German Silesia) open. Such an operation would also remove the last barriers to an invasion of Hungary.

Two Russian officers near the fortress of Przemysl. The Russian officer corps was rife with rivalries that included family hatreds, professional and parochial jealousies, as well as ethnic differences. These tensions often complicated major military operations.

Przemysl, however, was a much stronger position than Lemberg had been, even with the loss of the rail lines leading to Lemberg and Jaroslav. It held a more advantageous natural position and had been designed so that the outermost ring of fortifications protected bountiful fields and orchards that could keep a garrison supplied with fresh fruit and vegetables. Przemysl had also been stocked with more modern guns and had ammunition to supply those guns for months, if necessary. The Austro-Hungarian command had faith in the units it had stationed there and Przemysl was expected to be able to withstand a siege for eight months or more.

ASSAULT ON PRZEMYSL

The fall of Lemberg had also led the Austro-Hungarians to take more precautions with Przemysl. They evacuated the city’s civilian population, both to avoid the spread of panic and to ease food and supply requirements. Mostly Poles and Ruthenians, the residents of Przemysl were believed to have distinct pro-Russian sympathies; thus the Austro-Hungarian generals in charge of the region also saw a military value in their removal. More than 80,000 new Austro-Hungarian soldiers came into the region to bolster the original 40,000 men who held the outer defences, and they brought with them vast stores of all kinds. The local commanders boasted that Przemysl could easily withstand a siege until May 1915 without reinforcement or resupply.

‘The garrison of the fortress held Przemysl to the very last hour that human force could do so in the military sense of the word.’

Austro-Hungarian Minister forWar

The Russians completed their initial approaches toward Przemysl by 26 September. Rumours had reached Russian lines that the garrison of Przemysl was demoralized and suffering badly from cholera. The Russian commander sent a message by radio to the Austro-Hungarian commander of the fortress asking him what terms he would accept for a surrender. The general replied that all talk of surrender was impossible until he had exhausted all of his supplies and means of defence. Believing that the Austro-Hungarians were bluffing, the Russians decided to storm the outer fortifications, but they met with surprising resistance. Lacking siege guns and now unsure about just how strong the garrison of Przemysl was, the Russians decided to settle in for a prolonged siege.

October brought predictably deteriorating weather, greatly complicating Russian attempts to bring large siege guns forward. The guns did not arrive at Przemysl until March 1915. Without those guns, the Russians could not hope to inflict enough damage on the fortresses to compel their surrender. They therefore decided to bypass Przemysl and set up their defences on the approaches to it in order to cut it off from any Austro-Hungarian relief attempts. As Cracow, not Przemysl, was their ultimate objective, the Russians not unreasonably concluded that time was on their side, even as they received reports of large-scale concentration of German soldiers in Cracow to prevent the Russians from moving into German Silesia. They therefore decided that bypassing Przemysl in favour of pressing on with their advance on Cracow before the Germans could set up their defences was the best course of action.

The Russian decision meant little to the Austro-Hungarians in Przemysl where a cold, bitter winter wrecked havoc on the garrison’s morale and its health. News of the dispatch of German units to Cracow had boosted spirits, but when the Germans failed to come to their help, the men in Przemysl came to realize that they were being abandoned, not rescued. The Germans, they soon concluded, were in Cracow as part of a forward defence of their own interests in Silesia, not as part of a joint effort to rescue an ally. The men of Przemysl had been left to fend for themselves as long as they could, then they would have to face the Russians alone. By spring, they were low on ammunition, medicine and food. In March, the heavy Russian siege artillery finally arrived and began a systematic shelling of the fortifications.

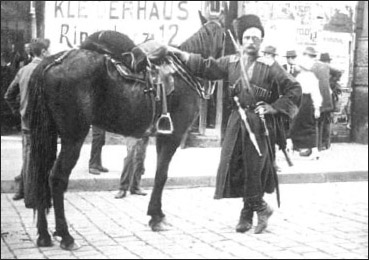

A Russian Cossack in Lemberg after its capture. The Cossacks had a particular reputation for cruelty, and were feared by their German opponents. They acted as the shock troops of the Russian Army and used their horses to increase their battlefield mobility.

Realizing that they could not hold out indefinitely against a heavy artillery bombardment, the Austro-Hungarian commander ordered a series of breakouts to find a favourable route of escape for as many of his men as possible. They all failed, as the report of the Austro-Hungarian Minister for War makes clear:

‘Events developed around Przemysl more quickly than was expected. The last sortie officially reported was directed towards the east, and was undertaken not with the view of effecting the relief of the fortress, but to find out if the surrounding Russian force was as strong towards Grodek and Lemberg as in the other directions, and whether the Russians had fortified their positions in the Grodek direction, as well as to the south and west of the fortress.

‘It was ascertained during the sorties that this was the case. The Russians, in fact, built counter-fortifications all around the fortress, even in the direction of their own territory, preparing for all eventualities.

‘In fact, the last reports coming from the fortress all confirmed the report that the Russians built a new fortress all around the besieged territory. The fortifications were so constructed as to constitute an impenetrable obstacle to inward attacks, just the counter-form of the fortifications and defensive works of the fortress itself. The Russian ring was constructed exclusively against Przemysl with unparalleled skill and rapidity, and with all available means of modern technology.

‘On the west a well fortified defending line and on the south a large Russian army stood in the way of any attempt to relieve Przemysl. In addition, the roads leading towards Russia were well fortified, as the last sortie proved.’

The garrison at Przemysl had held out for almost 200 days, finally capitulating on 22 March 1915. The Austro-Hungarians lost 100,000 men, most of them entering Russian prisoner of war camps as starving and diseased shells of the men they had once been. Most Germans and Austro-Hungarians expected the Russians to head south, over the Carpathian passes and into Hungary rather than advance on the forts of Cracow, which could offer resistance to a siege for at least as long as Przemysl had. Having shown no particular aptitude for warfare to this point, the Austro-Hungarian general staff was out of ideas and looked to their German allies for help. For their part, the Germans saw all of their worst fears about the Austro-Hungarians confirmed. They had, however, decided that they had to rescue the Austro-Hungarians, and that the way to do so was through a series of bold offensives to relieve the pressure on Hungary and drive the Russians back. Despite their success, the Germans knew that the Russians had taken heavy losses of their own in 1914 and had placed themselves in a difficult position to supply and reinforce. As was the case near Tannenberg, the Germans looked for places to take advantage of Russian overstretch and Russian sloppiness.

August von Mackensen (left) was the first commoner to be named a Royal Adjutant. In 1899 the Kaiser ennobled him. He was a corps commander at Tannenberg in 1914 and in the following year was named to command the Ninth Army. He would often wear the uniform of the 1st Life Hussars.

THE CAMPAIGNS IN POLAND AND THE BATTLE OF LODZ

The shattering Russian successes in Galicia in 1914 and early 1915 had occurred against the weaker Austro-Hungarian forces in the southern theatre. Further to the north, the much more powerful Germans conducted operations aimed at clearing the Polish Salient of Russian troops and capturing Warsaw. Fresh from their major successes at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, they expected to make relatively quick work of the Russians and hoped to deal them a fatal blow before the onset of winter made further pursuit impossible. A strike into Poland late in the year offered enticing possibilities, as it was close enough to Germany to allow for consistent lines of supply. The Germans could then spend the winter developing Warsaw and other cities as supply depots for campaigning in 1915.

For their part, the Poles had decidedly mixed loyalties. People who identified themselves as Polish lived in parts of the Russian, German and Austro-Hungarian empires. Thus ethnically Polish soldiers fought in the armies of all sides. While some Poles had an affinity with their fellow Catholics in Austria, most of them identified themselves as Polish and had few warm feelings for any of the great European powers. Nevertheless, the Poles knew that they sat in the area most likely to be fought over in any war in Eastern Europe. Most hoped beyond hope that the war might somehow lead to the establishment of an independent Poland, but even the most ardent Polish nationalists had trouble articulating a realistic scenario that might produce such an eventuality. When the war began the Tsar issued a statement promising Poles autonomy in the Russian Empire in return for their loyalty in the war, and the Germans soon followed suit with a similar pledge. While such ideas may have sounded better than nothing, most Poles looked upon them with a healthy dose of scepticism.

The German command team of Hindenburg and Ludendorff did not concern themselves with the problems of the national identifications of the peoples of Eastern Europe. They were too busy planning their next campaign. By mid-September 1914, the Germans had sent enough reinforcements to Poland to form a new army, the Ninth, based around Posen. A veteran of Gumbinnen and Tannenberg named August von Mackensen soon commanded it. Mackensen wore the distinctive headdress of his original regiment, the elite ‘Death’s Head’ Hussars. With its shako bearing an imposing skull and crossbones and Mackensen’s own strict military bearing, he was the very model of a German general. Like most of his German peers, he had full confidence in himself and his men. He also held the Russians in contempt and was as convinced as anyone that the German Army could repeat the thrashing of the Russians at Tannenberg almost any time it wished to do so.

When you know that the prison camps are all in distant, cold Siberia, try and think of the lot of prisoners. Yet for the moment the Germans were content. They were allowed to sleep. This is the boon that the man fresh from the trenches asks above all things. His days and nights have been one constant strain of alertness. His brain has been racked with the roar of cannon and his nerves frayed by the irregular bursting of shell. His mind is chaos.

One thing he knows, he must fire and fire and fire. It does not matter if the gun barrel blisters his fingers with its heat, never must it stop. That is the only way to hold back the line of wicked bayonets. When the bayonets come it is death or a Siberian prison camp. But when a soldier is once captured he feels that this responsibility of holding back the enemy is no longer his. He has failed. Well, he can sleep in peace now.

The fighting for the Bzura was a desperate, endless struggle. Days of seesaw battle found the Germans pressing the major part of their military might against the angle made by the Bzura and Rawka with the Pilitza River. Charge and counter-charge were the order of the day and night. Supermen, indeed, are these soldiers of the first line who stagger forward and back with repulse and attack.

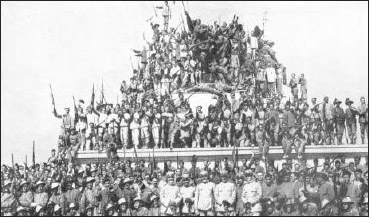

Some Slavs captured from the Austro-Hungarian Army volunteered to fight in the Russian Army in order to avoid the misery of the POW camps.

German troops assemble during the 1914 offensive on Warsaw. The city was the historic capital of Russian Poland and therefore was an important symbol as well as a key communications centre. It thus was a primary target of German operations.

Thus Mackensen took his new German Ninth Army into the field almost as soon as it had been created despite the fact that no fewer than three Russian armies sat opposite him and badly outnumbered him. He planned to smash in the centre (or face) of the Polish Salient, hoping to drive the Russians east and take Warsaw before the onset of winter forced a halt in operations. Hindenburg saw immediate value in the operation and hoped that as a side benefit, a German drive on Warsaw might distract Russian attention from Galicia and thereby provide the Austro-Hungarians with at least a modicum of indirect help. German engineers built roads through the forests and began converting the Polish railways to the German gauge as they advanced in order to ease supply problems.

Russian defences were in the hands of Nikolai Ruzski, a veteran if unremarkable general, who had the confidence of his friend Tsar Nicholas II. He had three armies under his command. The First Army, under Pavel Rennenkampf, had still not fully recovered from its thrashing at the Masurian Lakes and the Second, which had been mauled at Tannenberg, was still reorganizing under completely new leaders. The Russian Fifth Army came north to help bolster the line. Unable to form a solid defensive line with such disparate forces of such uneven quality, Ruzski opted to defend the major river crossings.

This strategy seemed to bear fruit in mid-October when the Russians used heavy artillery to turn back a German attempt to cross the Vistula near Novogeorgievsk and another near Ivangorod. The Russians then attacked and pushed the Germans back away from the Vistula, inflicting huge casualties at Kozience. Frustrated, the Germans called in Zeppelins to bombard Warsaw from the air, hoping to instil panic and confusion. They dropped 14 bombs, the first attack of its kind in Eastern Europe. The Germans, however, cancelled air operations when the Russians got a major morale boost from shooting down a Zeppelin and when it became obvious that the 1914 version of shock and awe would not achieve the desired ends.

On 15 and 16 October the Germans renewed their attacks on Warsaw, almost forcing the Russians to abandon the city. However, the weight of Russian numbers and the strngth of their artillery enabled them to hold on. Reinforcements arrived from Siberia, tough-looking men followed by ample stocks of ammunition and trainloads of food. Even erstwhile anti-Russian Polish nationalists enthusiastically cheered them as they arrived with a brass band leading the way. The Germans retreated to the northwest, torching farms and slaughtering livestock as they went, partly to prevent these resources from falling into Russian hands and partly as vengeance for the people of Warsaw’s support of Russia. This policy of scorched earth probably ended any possibility of Poles joining the German side, although Russian behaviour in the Polish countryside was often little better.

The Austro-Hungarian fortress of Przemysl held out longer than the fortress at Lemberg. It surrendered in March 1915, opening the route to western Galicia and the approaches to the strategic cities of Tarnow and Cracow.

Hindenburg was angry at the lost opportunity to take Warsaw and blamed the Austro-Hungarian failure in Galicia for freeing up too many Russians. He decided to begin placing Austro-Hungarian divisions inside the German Ninth Army command structure. He presented the idea to Conrad, the Austro-Hungarian commander, as a fait accompli, not as a proposal to be discussed, on 1 November. Conrad was stung by the insult to both the sovereignty of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his own military acumen, but, given the beating his forces had taken in Galicia, he knew he had no choice. The German Ninth Army became the Central Powers Ninth Army and was dominated by German commanders from top to bottom.

Now with full control of all of the Central Powers forces in the Polish Salient, Hindenburg and Mackensen began another drive for Warsaw. At the same time, the Russians misread their intelligence and mistakenly believed that the Central Powers were in full retreat from Poland and therefore exposed to an aggressive pursuit. They therefore attacked, choosing the junction of the German and Austro-Hungarian forces near Kielce. They succeeded in pushing the Austro-Hungarians back, confirming in Hindenburg’s mind the wisdom of his decision to begin the amalgamation of Central Powers forces under German tutelage. Russian Cossacks chased retreating Central Powers soldiers, cutting off their lines of communication and taking no prisoners. By 10 November, the Russians had almost cleared the Polish Salient of German and Austro-Hungarian forces and stood poised to launch deep attacks of their own.

THE RUSSIAN RESPONSE

The Russians were elated. They had seemingly proved that they had recovered from the twin disasters of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes. More importantly, they were simultaneously putting pressure on the Germans in the Polish Salient and the Austro-Hungarians in Galicia. Russian forces were within 32km (20 miles) of Cracow and some Russian patrols had ranged 24km (15 miles) into Silesia and Prussia. Grand Duke Nikolai took considerable pride in these victories, sending a telegram to his French counterpart Joseph Joffre that boasted of ‘the greatest victory since the beginning of the war’. Undoubtedly, Nikolai intended for the French to receive the subtle hint that at this point of the war the Russians had inflicted significantly more casualties and taken more land from the enemy than the French and British combined. Russia’s advance guards were just 320km (200 miles) from Berlin.

Nikolai could not have known that, on 10 November 1914, the Russians probably stood at the height of their power on the Eastern Front. Despite having inflicted tremendous casualties on their enemies, the Russians, too, had bled badly and had lost their most experienced officers and NCOs. Having advanced so far so fast, the fragile Russian supply system was showing signs of cracking. At the same time, the Germans were regrouping and reorganizing, promising to make any sustained advance into Silesia or on Cracow very bloody. More seriously, the Russians had advanced haphazardly, according to local conditions and the vagaries of geography. As a result, there were significant gaps between units, meaning that, as at Tannenberg, Russian armies had exposed flanks and could not easily come to one another’s aid.

German soldiers near Lodz. Located near Warsaw, the city was the scene of intense fighting in late 1914. The Germans eventually took the city, but at great cost, allowing the Russians to hold Warsaw at the end of the year.

Thus once again the strengths of the Germans could come into play against the weaknesses of the Russians. Hindenburg, aware of his inferiority in men and artillery, issued cautious orders, hoping to manoeuvre his units into the gaps between Russian armies and compel them to withdraw without fighting a major battle. Nevertheless, he told his commanders to look for opportunities for attacks against the Russians, whom he believed were ‘approaching the end of their tether’. Captured Russians reported that even officers had gone days on half rations or much less. Hindenburg therefore hoped to use German dexterity to move the Russians back by finesse if possible, by force if necessary.

The Russians used medium artillery pieces like this 15cm gun to destroy the fortifications at Lemberg and Przemysl. This gun’s design dated to 1877 and had limitations, but proved adequate against the Austro-Hungarian defences.

Within five days, the Germans had seemingly proved Hindenburg right. On 11 November, Mackensen had spotted an exposed flank in the unfortunate Russian First Army, commanded by Rennenkampf. The Germans drove into the flank and pushed Rennenkampf north, away from the Russian Second Army. Rennenkampf lost 12,000 men, most of them prisoners of war cut off from the rest of the Second Army by faster and suppler German forces. The situation looked too much like a replay of Tannenberg for Grand Duke Nikolai, who removed Rennenkampf from command on the spot and grew concerned that the Russian Second Army was about to be encircled once again. On 15 November, Nikolai ordered the Second Army to move to the supply depot of Lodz. He also sent thousands of reinforcements to the city to prevent the Germans from trapping the Second Army once again.

Hindenburg pointed to the surrender of almost 20,000 Russians in less than one week as evidence that his advance was breaking the will of the Russian soldier and at the same time securing Silesia from a Slavic invasion. The Kaiser must have agreed; on 17 November he promoted Hindenburg to field marshal, the highest rank in the German Army. Perhaps distracted by their own success, none of the senior German commanders noted that the Russian Fifth Army had covered 113km (70 miles) in two days through a snowstorm, giving the Russians a total of seven corps in and around Lodz. Even if he had been notified, it is unlikely that Hindenburg or his staff would have thought the Russians capable of such a feat. Ludendorff was mistaken enough to read Russian movements as preparations for a massive withdrawal to Warsaw and the Vistula River.

Thus, for once the Russians had surprise and the upper hand. Fighting at Lodz, moreover, put them near a supply centre and compensated for their poor lines of communications. By 18 November the Russians were close to encircling the Germans, but lacked the skill to complete the manoeuvre. A German corps broke through the Russian lines, then attacked the Russians from the rear, all through another snowstorm that literally and figuratively froze the Russians in place. The German corps seized 16,000 Russian prisoners of war and 64 artillery pieces. Confused officers in the Russian First and Second armies, fearful of another calamity, began to retreat back to Warsaw. Soon the city was full of wounded men and straggling soldiers looking for their units.

The Germans would certainly have liked to have pursued, but lacked the numbers needed to do so. With winter approaching they settled for occupying Lodz, then the second largest city in Russian Poland. They entered the city on 6 December, having flattened the face of the Polish Salient, although not as much as they would have liked. By the end of 1914, the Germans had seized 90,650 square kilometres (35,000 square miles) of formerly Russian territory and transferred more than 10 million Poles from Russia to Germany. The first year of the war on the Eastern Front had ended with more casualties, more movement and more men engaged than its more famous counterpart in the west. Like the Western Front, however, no one could predict what would happen in 1915 or how much longer the killing would go on.

The German invasion of the Polish Salient involved intense fighting amidst poor weather conditions. The Russians had better lines of communications into the salient than the Germans had around it, but the latter still managed to capture Lodz, a significant prize.

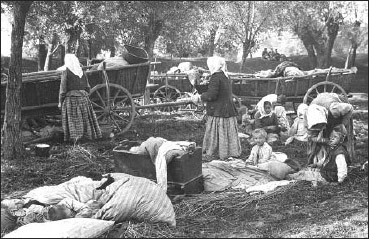

The fluidity of the Eastern Front caused tremendous hardship for civilians caught in the crossfire. Poles like these refugees were in an especially difficult position as their countrymen fought in the German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian armies.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF THE MASURIAN LAKES

Hindenburg stayed busy throughout the winter. He and Ludendorff reorganized German lines of communication, tightened the defences of Cracow in order to secure Silesia, and increased their hold over the units of the Austro-Hungarian Army in Russian Poland and Galicia. They also designed a new offensive to take place in the region of the Masurian Lakes aimed at securing the left flank of their new possessions in Poland and forcing the Russians to withdraw east of the Vistula River. The operation was to be two pronged. In the north the German Eighth and Tenth armies would attack the Russian Tenth Army in the narrow land corridors between the Masurian Lakes where they had achieved such a victory in 1914. In the south, Mackensen’s Ninth Army would make another drive on Warsaw.

Mackensen’s drive was a feint, but the Russians eagerly swallowed the bait. Hindenburg had ordered his intelligence officers to sweeten the pot by spreading the rumour that the field marshal had promised that he would capture Warsaw as a present for the Kaiser’s birthday, 27 January. The ruse worked as the Russians reinforced the Warsaw sector.

Using more than 600 artillery pieces, Mackensen’s artillerists opened up a furious barrage that convinced the Russians of the imminence of a major operation. On 4 February, the Germans attacked in a snowstorm, gaining an impressive eight kilometres (five miles) before deciding not to risk their gains; instead they headed back to more secure supply lines. The Russians succeeded in chasing the Germans and inflicting more casualties than Hindenburg and Mackensen had expected, but the diversion had done its job.

The main attack was to come in the north and the belated birthday present Hindenburg had in mind for the Kaiser was not Warsaw but another Tannenberg. Wilhelm had even transferred his headquarters from the west to the east to see his armies at work against the hated Slavs. Hindenburg had used the Russian concentration around Warsaw to move 300,000 men into East Prussia and had divided them into two armies. One of them had as its base Tilsit and the Niemen River, where in 1807 Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I had signed a treaty that enforced a new order for Europe. It had included French control over Warsaw and the humiliation of Prussia. In 1915 France and Russia again threatened Prussia, but this time the forces of the Kaiser were in an altogether different position.

The battle began on 7 February, as the actions around Warsaw were winding down. The Russians were taken by complete surprise and the Germans began an aggressive attack on the southern flank despite terrible cold and snow. Two days later the Germans hit the Russian northern flank, driving it in as well. In all the Germans advanced 113km (70 miles) in seven days. Another great German success seemed to be near at hand, but one Russian corps, the XXII, holed up in the Augustowo Forest and fought extremely well for more than a week, thus making the advance of the Germans on either side impossible. At one point a Russian cavalry charge in the forest almost brought the entire operation to a stop when it came close to grabbing the Kaiser himself.

Russian troops fight in the Polish Salient in 1914. Winter warfare posed special challenges of supply and movement. Normally, these challenges benefit the defender, and they did so in 1914 as the Russians withstood German assaults.

One way to deal with the bad weather common during the Eastern Front winters – Russian ski troops are shown here on patrol. Several Russian units were from icy places like Siberia and knew how to deal with the cold.

The battle, sometimes called the Battle of Augustowo or the Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes, was another disaster for the Russians. The German claims of 100,000 Russian prisoners of war were probably inflated, but not by too much. The Russians did manage to piece together enough men to contain the offensive and, alongside the worsening weather conditions, were able to keep the Germans from turning south towards Warsaw. The Kaiser proclaimed a great victory, claiming that ‘our beloved East Prussia is free from the enemy’, but the Russians were still in Warsaw and far from the end of their resources.

More seriously, the Russians had maintained important pressure on the Austro-Hungarians amid better weather in Galicia. By March, they had captured three passes in the Carpathian Mountains and, with the fall of Przemysl, the Russians were able to move thousands of men south. Any threat to Hungary had to be taken seriously because the critical grain fields there were central to German plans to compensate for food lost to the British blockade. Moreover, most Germans assumed that if Hungary looked weak, Romania would enter the war to get the spoils of Transylvania before the Russians overran it. Romania’s entry into the war, combined with a British success in the recently opened Dardanelles campaign (where naval attacks began on 19 February), would have drastic consequences for the Ottoman Empire and Central Powers’ fortunes in the Balkans. Thus, although about this time the Kaiser made his famous statement that the Carpathian Mountains were not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier, his generals knew better. The Austro-Hungarians would need to be saved from their own manifest incompetence in the Carpathians even if all other operations had to be put on hold.

GERMANY TAKES OVER

As a result of Austria-Hungary’s abysmal performance in the Galician campaigns, German senior officers had become convinced that, in the words of a phrase that made the rounds in 1915, they were shackled to a corpse. Italy’s signature to the Treaty of London (whose terms were secret, but generally suspected in Berlin) in March 1915 complicated the position of an already stretched Austro-Hungarian Empire and forced its army to plan to defend another front. Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary shortly thereafter and began combat operations in the Isonzo River valley in May. At the same time, the risk of the Romanians invading Transylvania had not gone away either. Austria-Hungary was suffering badly from its wounds, and the fact that many of these wounds were self-inflicted did little to help the Germans figure out what they should do next.

The German Albatros C.III biplane was a two-seat plane used mostly for reconnaissance. A 7.92mm machine gun is visible in the observer’s seat at the back. The plane had a long range that made it ideal for the spaces of the East.

They finally concluded that, corpse though it may be, Austria-Hungary was too important to German interests to allow it to be carved up by the jackals and vultures on its borders. An Austro-Hungarian collapse would sever Germany from its ally in Turkey and any possible future allies in the Balkans. More importantly, Germany needed Austria-Hungary to tie down tens of thousands of Russian soldiers (even if they did so ineptly) and secure the southern approaches into Germany. Finally, the Germans feared that their international prestige might drop even further if it appeared that they had abandoned their most important ally.

Thus, closing the lid on the corpse’s coffin was out of the question. But so was what German officers saw as the status quo of Germany defeating the Russians only to have the Russians compensate with massive victories over Austria-Hungary. The Germans therefore began to assume more and more dominance over Austro-Hungarian forces, with German officers taking command of more units and Austro-Hungarian forces even starting to wear German uniforms and use German equipment. German senior officers stopped consulting with or, in some cases, even informing their Austro-Hungarian counterparts on decisions regarding shared matters of strategy and operations. Austria-Hungary survived, but at the cost of becoming a virtual vassal state to their larger and more powerful ally.

Russian ski troops used as light infantry. Of special interest are the white uniforms that allowed the troops to blend into the snow and therefore be harder to spot from the air. The Russians did not have many such troops, but they were occasionally effective.

Italy entered the war in the spring of 1915 to gain territory at Austria-Hungary’s expense. Italy’s decision at once complicated and re-energized Austria-Hungary’s military position. Italy’s entry forced the Austro-Hungarians to find more men to defend yet another front, this one in the brutal conditions of the Julian Alps. On the other hand, the declaration of war from Italy, a former ally, appeared to most people in the empire as a blatant stab in the back. It thus led to a rise in morale, even among some of the ethnically Italian parts of the empire. The Italians soon became the one enemy that all peoples of the empire could agree to hate.

Italian Bersaglieri celebrate Italy’s declaration of war in 1915. Italy’s entry into the war forced the Austro-Hungarian Army to divert resources to another front. The Austro-Hungarians sent a Croatian general to that front with orders to hold the mountain passes along the Isonzo River.

THE STRATEGIC DILEMMA

From the perspective of Berlin, the survival of Austria-Hungary was important first and foremost for what it could mean for Germany. Throughout the winter of 1914/15 the Germans were locked in a heated argument about where the war might be won in the near future. ‘Westerners’ argued that no amount of lopsided victories in the east could knock out Russia and eliminate the Napoleonic nightmare of a deep pursuit into the barren steppes. They wanted a full effort on the Western Front dedicated to knocking out France and Great Britain which, they argued, would in turn force the Russians to sign a peace treaty that would allow Germany to keep its eastern gains. At this point, the westerners included several influential senior officials, including chief of staff General Erich von Falkenhayn.

The easterners argued that the war in the west had devolved into a series of sieges that would do nothing but attrite German forces and wear both sides out to no eventual purpose. They did not believe that the British and French lines could be broken, nor did they believe that any major strategic goal like Paris was within the short-term reach of German forces. They argued that the Germans in the west should straighten out their defensive line, dig stronger trenches, and go fully on to the defensive. Such a movement, they contended, could free up as many as 12 corps to be moved east for grand encircling operations against the Russians. Victories in the east, they argued, might knock the Russians out of the war, thus freeing up the full weight of the German Army to fight on the Western Front. At the very least, the Germans would add thousands of square kilometres of eastern territory to their empire, some of which they might even be able to trade back to the Russians in exchange for territorial or economic concessions elsewhere. Politically, the east held out the promise of more great victories on the scale of Tannenberg, or at the very least the possibility of the capture of major symbols like Warsaw. The west, by contrast, seemed to offer little but more inconsequential fighting.

Austro-Hungarian artillery moves into action; note the planks to help movement over the muddy ground. The empire’s economy was largely agricultural, and the strains of an industrial war began to show. The Germans provided help, but that help came with strings attached.

The debate failed to reach resolution so Falkenhayn finally settled on a compromise. He would launch a small offensive in the west to distract the French and British and to mask the movement of a limited number of troops that he would send east. The total number of troops fell far short of the 12 corps that many easterners had sought, but the transfers, as well as the arrival of new conscripts, would give the Germans enough men to launch a major offensive in the east in the spring. The western offensive became the Second Battle of Ypres, which began in late April. Lacking men because of the troop transfers to the east, Falkenhayn decided to employ poison gas for the first time on the Western Front. The gas created enormous gaps in the Allied line, but, lacking large manpower reserves, there were no troops to exploit the gaps thus created.

German Field Marshal Erich von Falkenhayn had little respect for his Austrian allies. He called them ‘childish military dreamers’ and the Austrian people ‘wretched’. He nevertheless saw the need to support the Austrians in their hour of need.

If the Second Battle of Ypres failed to give the Germans control of Flanders, it did meet its mission of masking the transfer of more German troops to the east. The Russians remained ecstatic over their capture of Przemysl in March and assumed that the German offensive near Ypres meant that the Germans would focus their efforts in the west in 1915. With the Germans in charge of staff work for the great eastern offensive, moreover, the Russians had a harder time divining enemy intentions than they had had with the notoriously porous Austro-Hungarian staff system.

The Austrian Schwarzlose machine gun’s design dated to 1907, but had received a modernization just two years before the war. It fired 8mm rounds at a rate of 400 per minute. It was dependable but among the heaviest of the war’s machine guns.

The German concentrations had placed nine field armies in the east, four of them north of Warsaw, one immediately opposite Warsaw and four south of Warsaw. The Russians were still more numerous and were fighting on their own territory. The significance of fighting in Russia lay less in some mythic attachment to Mother Russia and her sacred soil than in the fact that all railway lines in the theatre were on the Russian, not the German gauge. To compensate for their numerical inferiority, the Germans had worked carefully and deliberately to concentrate their assets in a region where they might obtain a local superiority of numbers.

The area they chose was the region between the towns of Gorlice and Tarnow in Galicia. The region sat near the Carpathian Mountains and was more than 240km (150 miles) away from Warsaw. The choice of Gorlice-Tarnow thus shows that the Germans were more interested in providing immediate assistance to the faltering Austro-Hungarians than they were in the final capture of Warsaw. Only if the breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow succeeded would an attack on Warsaw open.

The war in Serbia ended in a clear Austro-Hungarian victory, after German intervention. If the war had not expanded into a general European war, that victory might have ended the conflict, but instead it became just a minor sideshow to a much larger war.

All of the planning for the operation was German. Falkenhayn did not even see the need to inform his Austrian counterpart, Conrad, of the decision to attack until three weeks before the scheduled start date despite the fact that thousands of Austro-Hungarian soldiers (now commanded mostly by Germans) would take part. Perhaps the Germans were right to cut their allies out of the loop. By late April, they had concentrated 357,000 Central Powers troops in the Gorlice-Tarnow region against 219,000 Russians. They had also managed to create an advantage in artillery pieces in the sector of 1500 heavy guns to 700. The Russians never suspected either the size or the intentions of the Central Powers forces opposite them.

THE START OF THE OFFENSIVE

The German offensive began at first light on 2 May. For four hours all of the guns in the German artillery park fired along a 48km (30-mile) front. The idea of this short but intense ‘hurricane’ bombardment was to instil shock into the enemy, crush his barbed wire and provide the impetus for an infantry assault before reserves in the rear could be alerted and brought forward. The artillery would also clear the field of resistance in order to allow the presumably less sophisticated Austro-Hungarian units and the inexperienced recent German call-ups to fight at odds in their favour. Once the Russians began to panic and retreat out of their trenches, German shrapnel fire could decimate them in the open field, thus placing the burden of victory on the experienced gunners rather than the green infantry.

The plan worked to perfection. It took less than 48 hours for the armies of the Central Powers to break through the lines of defence formed by the Russian Third Army. Two Russian corps alone took almost 70,000 casualties in two days. The Russians had been caught in a redeployment of forces to the Carpathians in anticipation of a crossing of the passes into Hungary as soon as the snows melted. Thus, they could offer little help to the beleaguered forces at Gorlice-Tarnow. All the Russian headquarters could think to do was issue a rather silly order forbidding Russian soldiers to retreat.

The collapse of the Russians at Gorlice-Tarnow had immediate ripple effects all over the Eastern Front. Units at Gorlice-Tarnow themselves began retreating as many as 16km (10 miles) per day despite the high command’s order. As a result of their retreat, units in the Carpathians were now threatened with encirclement or being trapped against the mountains. They began their own retreat to the San River, but many never made it there as German advance guards reached the crossings and secured the bridges first. Russian units south of Warsaw were also at risk of being attacked in the flank or enveloped. The breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow had turned into a rout on a massive scale. In the first week alone more than 140,000 Russians fell into the hands of the Central Powers, so many that the Germans stopped keeping track of them. Unknown thousands more were killed or simply deserted.

Reports of prisoners are unanimous in describing the effect of the artillery fire of the [Germans] as more terrible than the imagination can picture. The men, who were with difficulty recovering from the sufferings and exertions they had undergone, agreed that they could not imagine conditions worse in hell than they had been for four hours in the trenches.

Corps, divisions, brigades and regiments melted away as though in the heat of a furnace. In no direction was escape possible, for there was no spot of ground on which the 400 guns of the Teutonic allies had not exerted themselves. All the generals and staff officers of one Russian division were killed or wounded. Moreover, insanity raged in the ranks of the Russians, and from all sides hysterical cries could be heard rising above the roar of our guns, too strong for human nerves.

Over the remnants of the Russians who crowded in terror into the remotest corners of their trenches there broke the mighty rush of our masses of infantry, before which also the Russian reserves, hurrying forward, crumbled away.

In barely 14 days the army of Mackensen carried its offensive forward from Gorlice to Jaroslav. With daily fighting, for the most part against fortified positions, it crossed the line of three rivers and gained in territory more than 100km.

What became known as the ‘Great Retreat’ was underway, whatever the wishes of the Russian high command to stop it. On 3 June, German units walked back into Przemysl without firing a shot, loudly singing patriotic songs as they did so. The fortification that the Russians had spent so much time and energy besieging, and finally capturing with such fanfare, had to be given back to the enemy. The Germans quite ungraciously made boasts about how easy it had been to take Przemysl back from the Russians and questioned how the Austro-Hungarians could possibly have lost it in the first place. By the middle of May the Russian armies had retreated more than 160km (100 miles) and by the end of the month they had lost an astonishing 410,000 men.

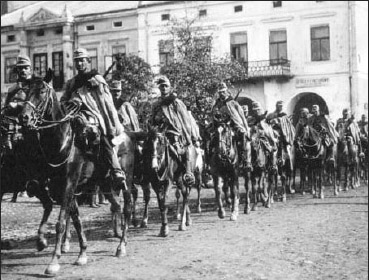

Austrian troops march back into Lemberg after the Russian retreat. The Germans took credit for the victory, although they did allow Austrian troops the honour of marching into the fortress. The incident further strained relations between the two Central Powers.

Success followed on success. In late June, the Austro-Hungarians got a bit of their pride back by retaking Lvov and changing its name once again to Lemberg. They then invited the Kaiser to come to Lemberg for a celebratory dinner, which he ungraciously held in Berlin instead, and without the presence of any Austro-Hungarian officials. Promotions flowed, with both Mackensen and Conrad being named field marshals. Austro-Hungarian supply problems eased with the capture of mountains of Russian guns and ammunition.

The massive Russian retreat that followed the breakthrough at Gorlice-Tarnow seemed to confirm in German minds their superiority to the Russians. The great victory, however, still failed to force Russia from the war, and the Eastern Front remained a persistent distraction for the Germans.

The Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive went so well for the Germans that in July they launched a second major offensive that aimed at the long-awaited capture of Warsaw. The original plan to encircle the city and its hinterland simultaneously from the north and south (and thereby trap hundreds of thousands of Russian soldiers) proved too ambitious, even for the Germans. They did, however, cut the main railway lines into the city and began a general attack all along the Eastern Front with what one reporter called ‘the most formidable [force] yet launched against the Allies’. Alongside the operations against Warsaw the Germans sent six corps into the Baltic provinces, where significant Baltic German populations, and thus sympathy for Germany, existed.

Toward the end of July the Germans concentrated a remarkable 45 corps with the final mission of securing Warsaw. The Germans planned to use these massive forces in a series of flank attacks aimed at cutting off all the roads leading into the city rather than attempting an urban battle in the city’s narrow streets. They hoped that the Russians would see that the threat was not just to Warsaw but also to the entire Russian Army if it committed itself to defend the city at the risk of encirclement. They knew that the Russians would have no choice but to sacrifice the city voluntarily in order to save what was left of their army.

The jaws of the Central Powers advance thus began to close on Warsaw. On 23 July the Germans crossed the Narew River and captured some key fortifications to Warsaw’s south. On 28 July, they began to cross the Vistula north of the city, bringing with them heavy siege guns and threatening both flanks. The last major fortification protecting Warsaw fell in due course, leading Hindenburg to invite the Kaiser to come to the front to witness the German capture of Warsaw, expected in a few days. More than 350,000 of the city’s residents were already in flight, clogging the roads and making any orderly Russian withdrawal (which Grand Duke Nikolai finally ordered) all that much harder to conduct. Rather than defend the city, Russian soldiers turned to dismantling as much of it as possible, taking factory equipment and metals with them to prevent them from falling into German hands.

‘The forest for miles looks as if a hurricane had swept through it. Trees staggering from their shattered trunks, and limbs hanging everywhere showed where shrapnel shells had been bursting.’

An eyewitness account of a battlefield near Warsaw, 1915

The Russians were reduced to taking extreme measures to stop the retreat. These men are local militia soldiers enlisted into the Russian Third Army. They were no more able to halt the retreat than the Russian regulars.

On the night of 3/4 August, the Russians gave the order for the withdrawal of the final units from the Warsaw region. At 3am on 5 August, Russian engineers blew up the last remaining bridges over the Vistula River. The first Germans pursued in pontoon boats, crossing the river just three hours later and walking into an eerily calm city. The Kaiser ordered public celebrations all across Germany. Perceptive German generals, however, noted that the seizure of Warsaw alone meant little to the overall German strategic picture. The Russians still showed no sign of quitting and were instead taking a page from Napoleon’s book. The Germans continued the pursuit and the Russians continued the retreat, surrendering the strongpoints of Brest-Litovsk on 26 August, Grodno on 2 September and Vilna on 19 September before heavy rains gave them some breathing space.

In the wake of the Gorlice–Tarnow disaster, the Tsar made the fateful decision to replace his uncle, the Grand Duke Nikolai, as commander of the Russian Army. Nikolai had led reasonably well to manage the disaster, reorganizing Russian forces and helping the retreat avoid becoming a rout. Nevertheless, the disaster was too great for the Tsar to keep the commander in his place. Having no one else of senior rank to turn to, the Tsar named himself as commander. He had virtually no understanding of the complexities of the army or of modern warfare, but hoped that his assumption of command would rally Russian morale. Most of the real work was done by the loyal but unpopular General Mikhail Alexeev, but when Russian military fortunes declined, the Tsar, not Alexeev, took most of the blame, with dramatic consequences for his regime’s survival.

German soldiers make a triumphant entry into Warsaw. Poles who had hoped that the expulsion of the Russians would lead to Polish independence were quickly disappointed when they faced an intense German occupation and exploitation instead.

The loss of territory was one problem for the Russians. The front line moved more than 480km (300 miles), forcing the Russians to give up Poland and significant parts of their Baltic provinces. The loss of men was even more serious. The Russian Army, in the words of one of its senior commanders was ‘melting like snow’. More than 800,000 Russians became prisoners of war or deserted. Exact figures remain a matter of conjecture, but most sources agree that the Russians lost two million men between May and September, losses that even the massive Russian Army could not easily replace.

In a rare moment of clarity and lucidity, Falkenhayn suggested using the massive victory to cut a deal with the Russians. He proposed to give them back most of what they had lost in 1915 in exchange for a peace that would enable the Germans to transfer men to the Western Front for a massive 1916 campaign. Few Germans heeded his advice. They looked aghast at giving back what they had conquered and worried that opening talks with the Russians would send the wrong signs to the British and the French. German industrialists, salivating at the chance to get access to natural resources in Poland and Russia, pressured the government to fight for even more territory. The war in the east would thus continue into 1916 and beyond.

For Austrian soldiers like these cavalrymen, the success at Gorlice-Tarnow was a mixed blessing. The Russians had been driven away from the Carpathian Mountain passes, but the Germans had assumed virtual control of the Austrian military, and would remain in charge for the rest of the war.