At the Chantilly Conference in December 1915, the Russians agreed to conduct an offensive in summer 1916, even though many people doubted that they had the capacity to do so. At approximately the same time, the British, French and Italians would also take the offensive.

Russia’s catastrophic defeat in the wake of the Gorlice–Tarnow Offensive signalled to most Germans and Russians alike that the Russian Army was on the verge of collapse. Nevertheless, the Russians conducted a successful offensive in 1916 that temporarily revived their fortunes and proved part of the old adage that Russia is never as weak as she looks.

At the end of 1915 the Germans could be forgiven for presuming that the Russians were at the end of their rope. They had been chased from Poland, had suffered repeated massive defeats and had shown that their system of war was wholly unsuited to the modern, industrial battlefields of 1914 and 1915. Russian generalship had ranged from uninspiring to abysmal, and the Russian transport and economic systems were already showing serious signs of cracking. Despite their ability to retreat into their own massive territory and call upon seemingly endless manpower reserves, Russia appeared to most Germans as a fatally wounded nation whose last death throes could not possibly be far away.

A Russian trench at Lake Naroch. It was part of the new defensive line the Russians constructed in the wake of the great retreat out of Poland. Russian soldiers were beaten, but not yet completely defeated.

The view in Paris and London was broadly similar. British and French military attachés reported on the mismanagement of the Russian armies and the manifest incompetence of the Russian state to handle the war. Russian offensives in the Caucasus theatre had gone little better than those in Poland, drawing Russian resources away from what the British and French saw as the main theatre of Russia’s war, Galicia. The Russians countered by reminding the British of their failure to help Russia’s cause by mismanaging their own campaign in the Gallipoli Peninsula, but the fact remained that after the Gallipoli debacle there were precious few places where the French and British might hope to provide some direct help to their faltering ally, even if they could spare the resources from their own fronts. Had the Gallipoli operation succeeded, the Russians could have closed down their Caucasus theatre and they would have had a reliable warm water link to their allies.

Nevertheless, almost as if to prove the second half of the adage that Russia is never as weak as she looks, the Russians decided they would attack in 1916. Russia still held an impressive overall numerical advantage over their Central Powers foes and still believed that they were militarily superior to at least one of the Central Powers, the Austro-Hungarians whom they had already beaten in Galicia. Russian generals with a sense of history looked back to a campaign a century earlier when long retreats had led to problems for an invading army, which eventually overextended itself and left itself exposed to a massive counterattack before withdrawing in disgrace, leaving Russia master of the field.

The Russians, therefore, showed up to a high-level inter-Allied conference at the Château de Chantilly in December 1915 in an optimistic mood and ready to discuss resuming the offensive. The conference was held in French commander Joseph Joffre’s palatial headquarters near Paris to discuss the coordination of Allied strategy for the coming year. The basic idea was to get all of the Allied nations to agree to launch more or less simultaneous attacks on the enemy sometime in the early summer of 1916. Joffre’s intention was to pressure the Germans so that they would be unable to transfer men and munitions from the Western Front to the Eastern Front as they had done that spring after the Second Battle of Ypres to help them prepare for the Gorlice-Tarnow Offensive.

The senior Russian representative at Chantilly was Yakov Zhilinski, the man who had so badly mismanaged the events that led to the Tannenberg and Masurian Lakes disasters. Zhilinski was, however, a familiar and welcome face to many French generals and for that reason had been sent to Paris to act as the Russian liaison officer to Joffre’s General Headquarters (GQG). After the drubbing the Russians had taken in 1915, the question of how to keep Russia in the war occupied many French and British strategists at Chantilly. Most feared a repetition of the 1905 Revolution in Russia that had been brought on by Russian failures in the war against Japan, although no one envisioned how much more fundamental a future revolution would be. The men at Chantilly saw the coordinated offensive scheme as a way to provide some desperately needed, if indirect, help to the Russians.

Zhilinski surprised many of the conferees by proclaiming Russia’s eagerness and ability to participate in the proposed joint offensive. He added Russia’s official support to two critical concepts enshrined in the Chantilly agreements. First, Russia would be prepared to launch a major offensive in June 1916 to coincide with a major Franco-British offensive to be launched on both sides of the Somme River. They would be the largest offensives yet conducted on the Western Front, using new French heavy artillery pieces and volunteer British Pals’ battalions then finishing their training in Britain and preparing to ship to France in large numbers. Second, the conferees agreed to launch local supporting offensives if one of the Allies were attacked before midsummer in order to prevent the Germans from redirecting their forces against one front exclusively. In exchange, Zhilinski demanded, and received, grudging French and British acceptance to keep the Salonika front open in Greece in order to draw some Central Powers troops (mostly Bulgarians) to the south.

Yakov Zhilinski bore a considerable amount of the blame for the twin disasters at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in 1914. Nevertheless, he knew the French better than any other Russian officer and represented Russia at the Chantilly conference which decided Allied plans for 1916.

The Nagant firm in Belgium designed this pistol for the Russian Army, just as it had designed the standard-issue rifle. It held seven 7.62mm rounds, but was underpowered owing to a design defect that was never fully corrected.

At the time, most Allied generals saw the agreements as ways to help the Russians and keep them in the war. Although they saw Salonika as a sideshow (Joffre had agreed to a British request to close it just a month before the Chantilly conference), keeping it open seemed a small price to pay to gain Russian agreement to resume the offensive in the near future. The agreement to launch supporting attacks was also a way to compensate for French and British inability to provide any more direct support to the Russians than a few Murmansk convoys carrying food, artillery pieces and ammunition. Little did the attendees know that the British and French would need the Russians to honour the agreements at Chantilly first.

The Russians did what they could to prove that they were far from vanquished. They used an unusually mild winter to conduct small, localized offensives designed to test the strength of the new German defensive line. Most of these attacks failed in the face of withering German machine-gun fire. In late January, the Russians turned their attention to the south, attacking along the Dniester River and capturing the Austro-Hungarian stronghold of Usciezko with a daring infantry attack. The success gave the Russians back a small bit of confidence and helped them to form a more or less defensible line across the Eastern Front.

But events in the west soon took centre stage. The careful planning at Chantilly became obsolete and irrelevant in late February when the Germans launched their massive assault on the French fortress city of Verdun. Erich von Falkenhayn had seen the attack as a way to attrite the French and thereby ‘knock England’s best sword’ out of her hand. Without France, England would have to leave the war and end the blockade. With the Western Front and overseas shipping lanes secured, the Germans could turn east and deal a deathblow to the Russians in 1917. Falkenhayn had not even bothered to inform his Austrian counterpart, Conrad, of the plan, revealing that inter-allied relations in the Central Powers were significantly worse than they were among the French, Russians, British and Italians.

The offensive at Verdun created a genuine crisis for the Allies. Joffre and the French GQG had been so obsessed with their plans for their midsummer offensive that they had left Verdun scandalously unprepared to meet the German attack. The unprecedented size and scale of the attack inflicted massive casualties and put the French in serious peril. Until they were able to recover and make some critical changes, it appeared that they might indeed lose Verdun, which would in turn have had serious, perhaps fatal, implications for their ability to continue the war.

Joffre urged his allies to meet their Chantilly agreements and launch offensives designed to distract the Germans and buy him and his new commander at Verdun, Henri Philippe Pétain, some badly needed time. The British demurred, arguing that their new soldiers were not yet ready to attack, a judgment Joffre reluctantly had to accept. The Italians launched a halfhearted and ineffective offensive in the Isonzo River valley that failed much as their others had. The Russians, who had originally seen the Chantilly agreement as a guarantee of French support if the Russians were threatened, now had, ironically enough, to launch an offensive of their own.

Russia and the Ottoman Empire fought one of the war’s most brutal and unforgiving campaigns in the snowy, frigid heights of the Caucasus Mountains. Amid poor communications networks and primitive supply systems, men died of diseases like typhus, cholera and frostbite as often as they died from enemy bullets. In February 1916 the Russians accomplished the stunning feat of capturing the Ottoman stronghold of Erzerum, which temporarily lifted the spirits of the Russian Army. In the following year, however, the Russian position in the Caucasus deteriorated as new Ottoman leaders found ways to move supplies to the region by sea. Although often forgotten by historians, the Caucasus theatre occupied much of the energies and resources of the Russians well into 1917.

Russian field artillery crews pause for a break in the sunshine. The Russians faced shortages of almost everything from artillery tubes to ammunition to horses. The large losses of 1915 also meant a crucial shortage of trained crews and officers.

THE BATTLE OF LAKE NAROCH

They decided to attack in Belarus with the ultimate goal of turning north and eventually recovering some of the ground they had lost in the Baltic provinces. The Russians had spotted a weakness in the German defences, where just 75,000 men guarded the southern approaches to the Baltic region. Against these German forces, the Russians assembled more than 300,000 soldiers and their heaviest concentration of artillery pieces to date, more than 1000 guns. The artillery would, presumably, compensate for the hasty preparations of the offensive and the relatively green quality of Russian troops engaged in the operation.

On 18 March, the Russian guns opened fire. Although the weight of shells fired was the heaviest yet seen on the Eastern Front, the accuracy left a great deal to be desired. Russian spotting techniques were primitive and correction of fire proved to be very difficult to organize. Consequently, the German positions, especially the machine-gun nests hidden in the woods, remained undamaged. The shelling continued for more than two days, giving the Russians a great deal of unwarranted confidence that the Germans would offer little resistance.

This photograph shows a handful of the hundreds of thousands of Russians who died in World War I. Russian losses were appalling, leading to charges of both incompetence and corruption at the Tsar’s court.

The Russians followed the artillery with a daring night attack by their infantry. They hoped that the darkness would provide further protection and cover for their inexperienced troops. It did not. German machine guns opened fire on Russian formations, which were unusually dense and thick in order to prevent separation in the darkness. Spring thaws turned the ground to mud and muck, slowing down the attacking waves and making command and control virtually impossible.

The first two Russian waves were destroyed well before they reached the German line. A third wave of attacks managed to seize a small portion of the German line, but the Russians soon lost it during a daring pre-dawn German counterattack. As dawn broke, the German artillery opened a devastating fire on the remaining exposed Russian positions over a 56km (35-mile) front.

Further to the north, the Russians had launched two supporting drives, one aimed at pressuring German forces west of Riga and the other at reaching Lake Naroch, the largest lake in Belarus. Russian troops managed to use a dense fog to infiltrate German positions and advance to the shores of the lake itself, but the Germans recovered and reestablished defensive lines. The Riga Offensive went nowhere and the Russians soon called it off. The Germans responded with carefully planned attacks preceded by massive artillery fire and, by late April, had recovered almost all of the lost ground.

The so-called Battle of Lake Naroch was a failure in every sense of the word. The Russians lost 70,000 men in the fight around the lake and another 30,000 around Riga. German losses were less than 20,000 combined. The Russians had taken no territory worth the losses nor, more importantly, had they done anything to cause the Germans to divert men or resources from Verdun. They had therefore bled themselves to no real purpose and seemingly proved once again their general inferiority in combat against the Germans, who read Russian methods as crude and Russian infantry tactics as suicidal.

The Lake Naroch and Riga attacks did, however, have the benefit of lulling the Central Powers into a sense of confidence. With German efforts in 1916 directed in the west, the Central Powers forces in the east would have to hold on as best they could with the resources they had on hand. As the French recovery at Verdun continued, moreover, the Germans found themselves having to commit more and more resources to a battle that was quickly devolving into a slaughterhouse for both sides. Most Germans in the east, however, were not worried. Riga and Lake Naroch had seemingly demonstrated to them that they could contain and reverse any offensives the Russians attempted. They remained concerned about the ability of their Austro-Hungarian allies to do likewise, but with all eyes fixed on Verdun, there seemed little cause for worry.

THE BRUSILOV OFFENSIVE

The failures at Lake Naroch and Riga did nothing to dim Russian enthusiasm for keeping their promise to launch a midsummer offensive. The crisis at Verdun remained, as did Russian desires to prove their mettle and recover their lost territories from the occupying Germans. Joffre continued to urge both the Russians and the British to offer any help they could by launching any offensives at all to distract even a small part of Germany’s efforts away from Verdun. In May, the Italians added their calls for help when the Austro-Hungarians launched an offensive in the South Tyrol. Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel III personally appealed to Nicholas II for help. Although then serving as nominal commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, the Tsar had a difficult time finding any enthusiastic generals for another offensive designed to help out a distant ally, especially at a time when Russia herself seemed to be teetering dangerously on the edge of collapse.

The only commander anxious to attack was the aggressive and talented Alexei Brusilov, recognized then and now as Russia’s best general of the war. In April, he had been named to replace Nikolai Ivanov as commander of the Southwest Front, encompassing all of the armies south of the Pripet Marshes. He had led well in the war’s first months and had worked hard to rebuild his shattered armies after the disastrous retreat that followed the Gorlice-Tarnow breakthrough. He believed that his men were ready to attack and that he had a plan that stood a more than a reasonable chance of success. Not coincidentally, his Southwest Front faced the Austro-Hungarians, whom the Russians believed were ripe for destruction.

‘Russia has not yet reached the zenith of her power, which will only be approached next year, when she will have the largest and best army since the beginning of the war.’

Brusilov’s official report on his offensive

Brusilov had examined the Russian failures at Lake Naroch and Riga and rejected fashionable (and exculpatory) views inside Stavka that blamed the poor quality of Russian munitions or the low state of Russian morale. Instead, he concluded that the offensive and its supporting artillery had been too narrowly concentrated. Concentrating fire had seemed sensible enough given the inaccuracy of Russian gunners and the paucity of Russian artillery reserves. But Brusilov thought that this method had channelled Russian soldiers through gaps in the enemy line that were far too narrow, exposing them to the full fury of devastating German machine-gun and artillery fire.

Brusilov was an aristocrat by birth and a cavalryman by background. He had, however, come to understand the changes in modern warfare much better than most of his peers. He was meticulous about training his men and very careful about staff work. He was also one of the first aristocrats to realize that the Tsarist system was broken beyond repair and needed to be replaced. Accordingly, he supported the Tsar’s abdication and later even offered his services to the Bolsheviks, helping to lead the Red Army to the gates of Warsaw in the Russo-PolishWar. He published a memoir of his wartime experiences that provides one of the best looks inside the Russian Army at war.

Convinced that Russian soldiers could still fight effectively if properly led and trained, Brusilov set to work. He aimed to launch his offensive over a broad front to give Russian forces the chance to break through at several points (as the Central Powers had done at Gorlice-Tarnow) and remove the flanks from which the enemy could pour his deadly enfilading fire into advancing Russian formations. This method required a massive artillery preparation, something the Russians were incapable of producing. Thus the offensive would need to safeguard itself by ensuring absolute secrecy. Only at the last minute would Russian gunners open up a brief, but devastating fire to clear the way for the infantry.

Secrecy would also help Brusilov solve another problem, that of the reserves. Typically, when the Russians had made sizeable gains in offensive operations, they had stalled when the Central Powers had rushed reserves forward. To overcome this problem, Brusilov wanted to mass Russian reserves just behind the front lines. These men could launch simultaneous attacks on multiple parts of the front to confuse and disorient the enemy, forcing him to stretch his reserves dangerously thin. They could also be used to exploit areas of success and conduct pursuit of enemy soldiers in the open field.

Aware of the limited number of shells that Russian gunners would be able to fire, Brusilov knew that accuracy would need to be improved. He forced gunners to spend time in the front lines in order to acquaint themselves with the problems infantry faced. He also had them work out better methods of communication so that field artillery units could provide fire support on the move. Although cavalrymen were not generally noted for their acceptance of new technologies, Brusilov embraced aviation and its capacity for high-level aerial reconnaissance. He ordered his aviators to photograph the Austro-Hungarian lines, helping his gunners find the locations of the majority of the enemy’s artillery pieces, which they could then target in the opening phases of an attack in order to silence the enemy’s most powerful weapons.

Russian lines after the great retreat from Poland were straight, thus eliminating salients, or exposed bumps in the line. Salients were hard to defend and required extra manpower to guard against attacks from several directions at once.

Secrecy was vital. Brusilov would need to conduct training in new methods to thousands of soldiers and amass reserves close to the front line, normally a sure sign of an impending attack. Secrecy and subtlety had not normally been associated with the Russian Army, so Brusilov took many precautions. He was noticeably tight lipped around officers from the Stavka and people with connections to the Tsar’s notoriously gossipy court. He also kept his own counsel, guarding his plans even from several of his key subordinates. Although he routinely visited the trenches to make sure that his preparations were being carried out as ordered, he did not often chat with junior officers or take them into his confidence. Like many Russian aristocrats, he was uneasy his social inferiors and this desire for remove helped to underscore his secrecy.

Brusilov also ordered minute preparations uncommon for most Russian operations and supervised them personally. He ordered the construction of scale model Austro-Hungarian trenches behind the lines based on aerial reconnaissance, as well as new communications trenches to move men and supplies forward efficiently. Extra dugouts in the trenches safely concealed masses of Russian troops from enemy aviators and observation posts. Lastly, he replaced commanders he found wanting and struck the appropriate level of fear into many others. Brusilov’s forces soon became a model for the Russian Army, although few other commanders were able to do what he had done.

These Austrian infantrymen were the lucky ones. They were still alive in 1916. Thousands of the men they went to war with in 1914 were already dead. Casualties were especially high among junior officers, who often led from the front.

For their part, the Austro-Hungarians were not expecting a Russian offensive at all. They had become obsessed by what they saw as the treasonous behaviour of Italy and had dedicated most of their staff energies to planning the South Tyrol Offensive. To give that offensive every chance of success, they had moved six infantry divisions away from Galicia, much to the consternation of the Germans, who doubted that the South Tyrol Offensive would achieve any goals worth the men and munitions dedicated to it. The weaknesses of Austro-Hungarian forces in Galicia meant that their units were pushed far forwards in what was derisively known as a ‘shop-window’ defence, with a lack of reserves to the rear. Brusilov had a reasonably accurate picture of the Austrian defences from aerial reconnaissance and had guessed that if he could smash the window, his men might be free to range almost at will against the Austro-Hungarians, taking them from behind and scoring a great victory.

These men were not as lucky. They are Austrian POWs being marched off to Russian camps. There they faced a grim and uncertain future – many of the camps were in Siberia. Thousands of men died in captivity, although the exact numbers remain unknown.

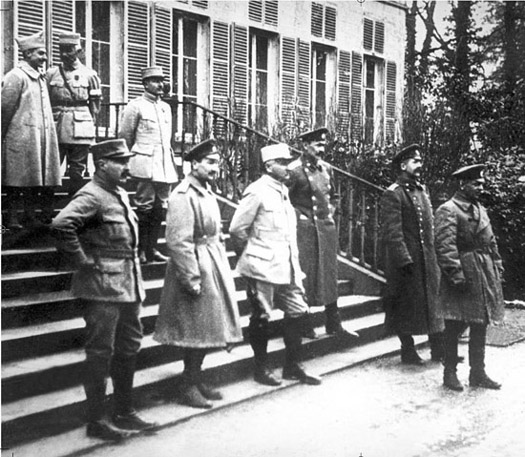

Brusilov had four field armies under his command. He intended to use them to strike consecutive blows along a front line of more than 30km (19 miles). Among the targets of the first waves of attacks were the town of Lutsk, where several key roads converged, and the town of Kowel, which commanded the north to south railway that led to Lemberg. In the region of the two towns, Brusilov had deftly and carefully concentrated a numerical superiority of 125,000 men. By mid-May he had completed his preparations, but at the last minute had to convince an anxious Tsar and Stavka that he could attain his goals and achieve success where previous Russian offensives had failed. Two of Brusilov’s own army commanders practically begged him to call off the attack; they were afraid that the secrecy needed for so large an offensive could not be maintained and that the Austro-Hungarians must surely have picked up some sign of the impending attack. One of the army commanders may have even suffered a nervous breakdown, which required Brusilov to make several trips to his headquarters in order to bolster his confidence. The risks were indeed great. Running low on both supplies and public faith, the Russians could not afford another disaster, and morale was still unsteady after Gorlice-Tarnow and the subsequent Great Retreat from Poland.

Brusilov fumed at the delays imposed upon him by men thousands of kilometres away, but the extra few days inadvertently helped him. The day Brusilov finally set to start his offensive was 4 June, coincidentally also the birthday of the Austro-Hungarian Fourth Army commander, Archduke Josef Ferdinand. He was the godson of Kaiser Wilhelm II and, out of family courtesy, had been spared the kinds of direct German oversight that other officers had experienced. He was arrogant and unwilling to listen to the advice of the professional officers around him. His domineering and manipulative wife, the Archduchess Isabella, burned for the chance to become empress and played politics both in Vienna and at her husband’s army headquarters. For his part, he spent much more of his time womanizing and hunting than he did preparing his army for war. For her husband’s 44th birthday Isabella had planned a massive dinner at the castle of Teschen and had drafted several members of the Fourth Army staff to help her deal with the myriad of details involved. She had invited Conrad who, believing that no military operations were imminent, had accepted.

Brusilov designed his offensive carefully. His attack was delineated to the north by the Masurian Lakes, which guaranteed that he would not be outflanked from that direction. He therefore could place more troops in the vanguard of the attack.

Thus when the Russian guns opened fire on 4 June they caught the Austro-Hungarians utterly unprepared. Reports of massive Russian attacks filtered in to Conrad’s headquarters, which relayed them to Teschen. Conrad saw nothing in the reports serious enough to cause him to risk offending the Archduchess by leaving the party early. He told his staff officers that the Russians had made a temporary gain and that his men would correct it after the Russians had moved forward a few hundred metres. He sent directives to his field commanders to hold the line, then, as one version of the events had it, returned to his card game with his apologies to the ladies for his absence.

He might well have made the right choice, because by then the situation was already out of his control. Brusilov had ordered his artillerists to fire a fast and furious hurricane bombardment that chased Austro-Hungarian defenders into their deep dugouts. Lighter field guns targeted the thin layers of barbed wire that protected the Austro-Hungarian trenches and the known placements of Austro-Hungarian artillery pieces and machine guns. The artillery did most of the work; Russian infantry then only had to follow up, surround the trenches and wait for their enemies to come out of their dugouts with their hands up. Thousands did so, especially ethnic Slavs who had little desire to fight and die for the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

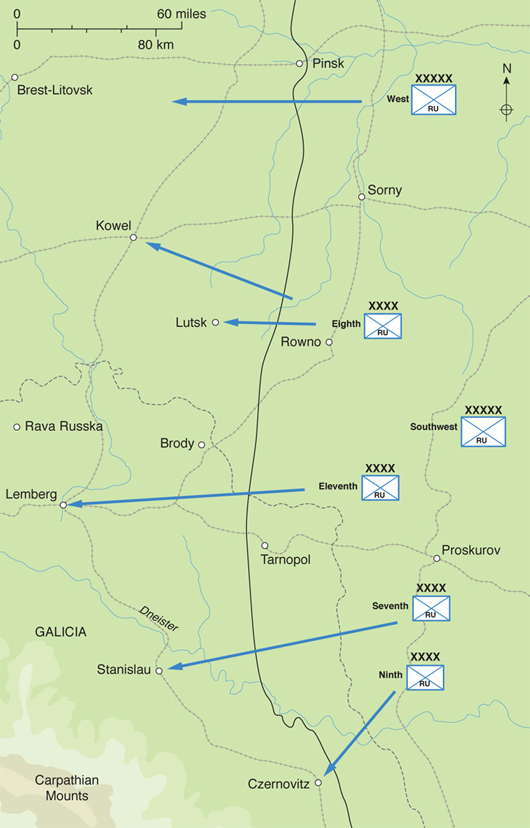

The Fourth Army’s shop window had shattered and elements of the Russian Eighth Army were moving behind it, taking Austro-Hungarian units in the flank and creating chaos. The demolition of the Austro-Hungarian Fourth Army necessitated the staged withdrawal of its neighbour, the Seventh Army. It had no choice but to retreat south, placing it hard against the Carpathian Mountains. The First Army also withdrew, thereby putting the entire Austro-Hungarian position in considerable danger. Whole units began to melt away. In some cases, regiments, mostly Czech and Ruthene, walked to the Russian lines and surrendered as a unit. Some men even switched sides and joined the Russians, believing that the final collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire could not be far away.

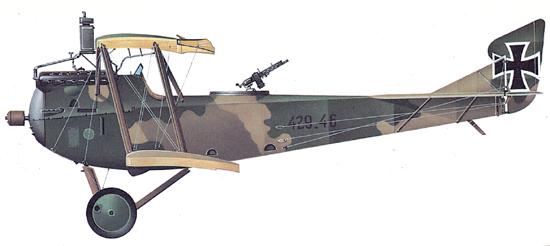

The Hansa-Brandenburg C.I biplane was a German-built reconnaissance plane flown mainly by Austro-Hungarian pilots. Although it was not designed as a fighter, 12 Austro- Hungarian airmen became aces while flying it

By the third day of the offensive, the severity of the situation was plain for all to see. The Russians had torn open a sizeable hole 32km (20 miles) wide in the Austro-Hungarian front. Hundreds of thousands of Austro-Hungarian troops were prisoners of war or had simply fled from the battlefield. By 8 June, the Fourth Army, which had had a field strength of 110,000 men one week earlier, had just 18,000 men under arms. Reports suggested that as many as 60 per cent of the Austro-Hungarian casualties were deserters from their units.

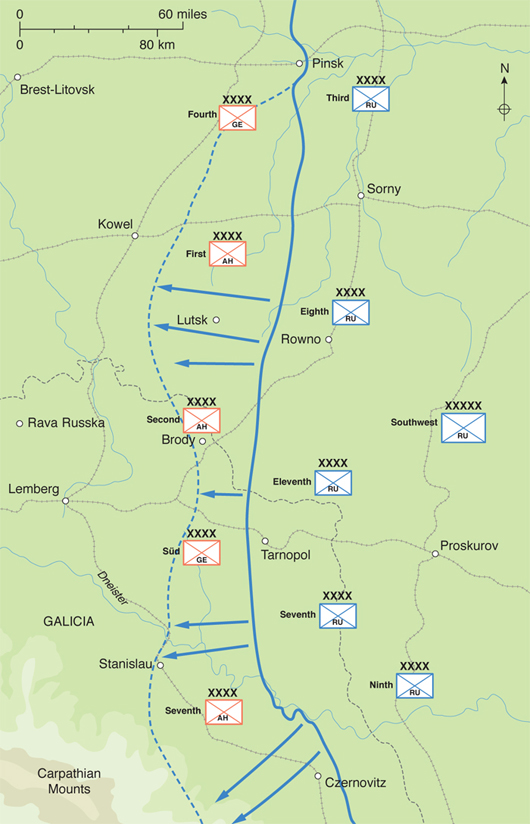

Evert was a strong monarchist and a close confidant of the Tsar. Upon naming himself commander-in-chief of the Russian Army, Nicholas II overlooked Evert’s many shortcomings and promoted him to commander of the West Front. His poor performance at the Battle of Lake Naroch failed to convince the Tsar to remove him. Instead, he accepted Evert’s arguments that he had failed owing to insufficient stocks of artillery shells. Evert’s caution caused the Brusilov Offensive to lose steam far too early, but again he successfully deflected all criticism, at least in the Tsar’s eyes. When the Tsar abdicated, Evert was removed from command. He went into hiding when the Bolsheviks took over and died under mysterious circumstances.

Brusilov had designed a masterpiece. Austro-Hungarian units were in retreat along a massive 400km (250-mile) front from the Pripet Marshes to the Carpathian Mountains. Several Russians began to boast that their country would prove ‘the saviour of the Entente’ and that the Brusilov Offensive would save the French from the killing at Verdun. Dreamers at Stavka headquarters began to envision a massive Russian crossing of the Carpathians into Hungary and the recapture of Lemberg.

Alexei Evert (right) conferring with other senior officers at Russian headquarters. He did not share Brusilov’s faith in the offensive and reacted too slowly and too cautiously. His inaction gave the Germans time to recover and reinforce.

A combination of German action and Russian inaction soon turned the tide, however. Conrad became awake to the terrible peril his army faced, but was aware that he could do little to stop the bleeding without more help from the Germans. He therefore headed to Berlin for a meeting with Falkenhayn on 8 June. He began in undiplomatic fashion by telling Falkenhayn that his offensive in the South Tyrol was working whereas the German attack at Verdun was not. He therefore asked Falkenhayn to wind down the Verdun offensive and transfer troops to the South Tyrol so that the Austro-Hungarians could move men from the South Tyrol to the Carpathians. He also suggested that all German forces moved to the South Tyrol be placed under Austro-Hungarian command.

Whatever Conrad was expecting to accomplish, he got quite a rude reception. Falkenhayn screamed at him, belittling Conrad’s strategic vision and lecturing him for his senseless obsession with a meaningless operation in the South Tyrol. Falkenhayn all but ordered him to shut the offensive down and move four divisions to the Carpathians before it was too late. He then informed Conrad that German reinforcements were already on their way to railway stations for immediate dispatch to the Carpathians but that they would only arrive if all Central Powers forces came under direct German control on the model of Mackensen’s Ninth Army. Falkenhayn then warned Conrad that if he failed to accept the terms, Germany would send no help at all and Russian forces would be free to cross the Carpathians whenever they wished.

Falkenhayn was most likely bluffing. He knew that the Germans still needed the Austro-Hungarians, even if he often derided them as ‘childish’ and ‘military dreamers’. Conrad sheepishly accepted Falkenhayn’s terms, but the two were never on good terms again. Falkenhayn dispatched German forces east under the command of General Hans von Seeckt, who soon assumed command of all Central Powers forces in the southern theatre, much as Mackensen had in the northern. The Austro-Hungarian general staff retained control of its operations in the Italian and Balkan theatres, but in Galicia it had become a virtual subordinate formation to the Germans.

The next day, 9 June, was supposed to witness the opening of Brusilov’s second phase. The troops that had fought in the first few days of the attack were to rest and await supplies. Brusilov did not want his men to outrun their supply lines and thereby leave themselves exposed to a Central Powers counterattack. To keep the momentum of the offensive going, the West Front, under the command of Alexei Evert, was to have begun its attack. But Evert demurred, arguing that he was not ready and that he needed to wait for more artillery shells before going on the offensive. Brusilov accused him of turning a hard-won victory into a humiliating defeat, but Evert could not be budged. With the men of Evert’s front not moving forward and those of Brusilov’s front in need of time, the offensive stalled.

Archduke Josef Ferdinand (right) had family connections in Austria and in Germany that allowed him to stay in command despite his lack of military acumen. His poor generalship was painfully exposed by the Brusilov Offensive in 1916.

The Germans used the time very wisely. By the end of the first week in July, the Germans had moved four divisions from France (although these had little impact on the fighting at Verdun or the fighting that began on the Somme) and five more divisions from reserves in the east, along with 98 artillery batteries, to the Carpathians. Hindenburg later added another division out of his general reserve. Falkenhayn also made certain that the Austro-Hungarians moved the four divisions out of the South Tyrol as promised. These reinforcements secured the Carpathians and helped to restore order.

Russian soldiers pose with trench mortars. These weapons had a high enough angle of fire to place shells inside trenches and were light enough to move easily. They gave a measure of local firepower to infantry units.

As the situation stabilized and no second Russian attack materialized, Conrad’s spirits soared. Incredibly, Conrad chalked up the disaster to bad luck and the poor decision making of a few subordinates.

He began to prepare for a resumption of the offensive, asking Falkenhayn once again to move men from Verdun to the east in preparation for a double envelopment in the region east of Lemberg. Falkenhayn instead told German troops to set up solid defensive lines, restore discipline and assume command of Austro-Hungarian units as small as companies. Conrad was only deluding himself by dreaming of renewing the offensive. In Vienna, senior officials began to scheme to get rid of him. Although he held on to his job for a while longer, he was no longer the commanding authority he had once been. Instead, he was boxed in both by the domineering attitude of his German allies and the suspicions of many in the Austro-Hungarian government.

Many military historians point to the Brusilov Offensive as the effective end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Thereafter, it began a steep descent into irrelevance, becoming an effective state of the German Empire without much say in its own future. The Austro-Hungarians were also deeply in debt to German bankers, adding further to the reliance on Berlin. On 27 July, Hindenburg received control of all military operations in the east and a new title of supreme commander of the Eastern Front. On 6 September, this military move was followed by an essentially political one with the creation of a United Supreme Command, with Wilhelm II as the titular head.

Russian officers occupy trenches in the Austro-Hungarian front line following the early successes of the Brusilov Offensive. The initial advances were so successful that second- and third-stage objectives were taken with ease; however, the momentum did not last.

Although these moves meant the end of their sovereignty, the Austro-Hungarians were aware that they had little choice. Without German help, they feared that the Russians would in all likelihood cross the Carpathians and begin to pillage or occupy Hungary. They needn’t have worried quite so much. Russia was certainly ascendant, but Russia was not as strong as she looked. Russian casualties had been nowhere near as high as Austria-Hungary’s, but the Russians could ill afford the losses. Even in victory the losses led many to question the value of the war and the ultimate benefits to the average Russian even if they did win. Desertions increased, as did indiscipline.

Russian forces advancing during the Brusilov Offensive. Their initial success was dramatic, but also very costly and, in the end, it could not be sustained.

Evert’s failure to attack increased the demoralization of many soldiers. At Stavka, Alexeev generally accepted Evert’s rationales, but railed at the opportunities Russia was missing. The Austro-Hungarians were reeling and Russia had a chance to attack them and finish the job before the Germans had the time to arrive in strength and reinforce the line. According to some estimates, the Russians had a manpower advantage of 800,000 to 450,000 in Galicia, but if the Russians did not attack, the advantage would come to naught. Alexeev therefore ordered Brusilov to attack again. Brusilov, still furious that Evert was remaining in place, objected at first before finally relenting.

Russia’s aviators did not earn themselves a great deal of distinction during the war, but their reconnaissance efforts paid off in 1916. They also used machine guns to strafe and terrorize retreating Austro-Hungarian soldiers, echoing developments in air combat on the Western Front.

Brusilov attacked again on 27 July and routed the remnants of the Austro-Hungarian First Army. The next day the Russians moved against what was left of the Fourth Army and routed it, too. Still, Evert stayed in place, leaving Brusilov to try again alone. From 7 August to 20 September, the Russians kept pushing, but stiffer resistance from German units made the going much slower and much costlier. Alexeev and the Tsar demanded that Russian forces finish off their enemy, but even though Evert reluctantly began to send units into combat, Brusilov understood that the offensive had reached the point of diminishing returns. Although they had inflicted one-and-a-half million casualties on the Austro-Hungarians (leaving the Austro-Hungarian Army with just 700,000 men in arms), the Russians had also taken one million casualties, most of them in the offensive’s later stages. Along with the manpower losses came the losses of tonnes of equipment that could not easily be replaced. Russia had achieved its most spectacular victory of the war, but it had proved in the end to be Pyrrhic, further weakening and destabilizing the Tsar’s already shaky hold on his empire.

The Brusilov Offensive also had ramifications for Poland. The Kaiser discarded a plan to transfer the crown of Poland to the Habsburg royal family, and instead announced the creation of a new Polish vassal state under the control of the German Empire and with its capital at Lublin. Ludendorff and others drew up plans to recruit hundreds of thousands of Polish soldiers, whom they presumed would want to defend their new homeland against Russian aggression and what the German foreign ministry termed ‘Jewish masses’. In the end only 4700 Poles volunteered.

ENTER ROMANIA

Poland was not the only small nation whose fate hung in the balance. Romania sat in a geographic position that gave it many options. Although a small and poor country by great power standards, it bordered Russia, Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary and Serbia, and also sat close to the Ottoman Empire. Thus it presented at least the possibility of opening up new fronts for both sides. Sitting on valuable grain and oil fields, Romania in theory offered quite a lot to a prospective ally, but its army had performed terribly in the Balkan Wars and few Europeans thought Romania was ready for modern warfare. Its general staff was regarded as worthless, even by foreign observers generally sympathetic to the Romanians. The country had had little money to modernize its armed forces after the Balkan Wars and by almost every material measure, the Romanians looked more like a nineteenth-century army than a twentieth-century one.

Like Italy, the Romanians had no vital national interests at stake, and therefore had little reason to worry about being dragged into the war. Such ties as had existed for the Romanians all pointed to the Central Powers. Fears of the Russians had led to a secret treaty with Austria-Hungary in the 1880s, although the terms did not require Romania to go to war in 1914. Most of Romania’s key economic links were with Germany and the Romanian royal family was a branch of the Prussian Hohenzollerns. The Prime Minister and most senior government officials were also pro-German. Although Queen Marie was the granddaughter of an English and Russian monarch (Queen Victoria and Alexander II), both of the king’s brothers had chosen service in the German Army.

Austro-Hungarian soldiers retreating in the wake of Brusilov’s success. The attack soon turned into a rout, with thousands of Austrians surrendering or deserting, another indication of the cracking morale.

Nevertheless, the Romanians, again like the Italians, had political aims that could only be satisfied through war against Austria-Hungary. As Italy sought territories with large Italian populations like Trieste and Fiume, so too did the Romanians seek Transylvania with its large number of ethnic Romanians. The Bukovina and the Banat also held Romanian populations that many nationalists coveted. Not coincidentally, these regions were also lucrative from an economic standpoint. War against Russia could only gain the Romanians a non-Romanian territory like Bessarabia and the undying enmity of a powerful neighbour. Perhaps most importantly, few Romanian generals liked the idea of joining the Central Powers and thereby fighting on the same side as their recent Ottoman enemies.

With his monocle and his icy stare, Hans von Seeckt seems to be almost a caricature of a German general. Assigned to be August von Mackensen’s chief of staff in early 1915, he received the lion’s share of the credit for the planning that led to the Gorlice-Tarnow breakthrough. He then served in a variety of positions aimed at reforming the Austro-Hungarian Army and making it more like its German counterpart, earning a number of enemies in Vienna in the process. Known for his organizational and management skills, he rose through the ranks quickly. After the war he replaced Hindenburg as chief of staff and built the 100,000-man German Army that the Versailles Treaty permitted. He later turned to the Nazis and died in 1936.

Ironically, what settled the Romanians on entering the war was the success of the very Russians they feared. The Romanians assumed that a Russian victory would mean Russian control of the Carpathians and, perhaps, Constantinople and its hinterland. In early 1915 the Romanians concluded secret agreements with the British in which the British pledged that they would support Romanian acquisition of Transylvania if Romania entered the war. Shortly thereafter, the Russians collapsed during the Gorlice-Tarnow disaster and seemed more likely to be knocked out of the war than win it. Germany had made no promises about any future Romanian control of Transylvania, so remaining on the sidelines seemed to make the most sense to Romanian officials.

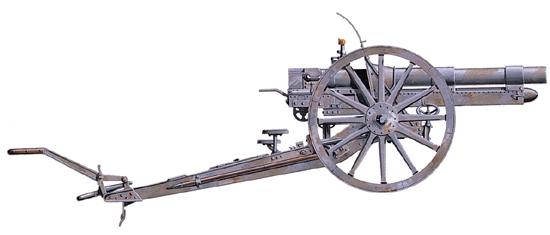

This Romanian 75mm field gun was manufactured by the German firm of Krupp. It symbolizes the tight links between Romania and Germany before the war. Nevertheless, Romania entered the war against Austria-Hungary in hopes of gaining Transylvania.

Romanian cavalry advance toward Transylvania in 1916. The Romanian Army was badly outclassed and still suffering shortages incurred during the Balkan Wars. Militarily, it was far from ready to fight a war in 1916.

All that thinking changed when Brusilov brought Russian troops to the foothills of the Carpathians in June 1916. It seemed obvious to everyone in Bucharest that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was ready to implode and that Transylvania, Bukovina and the Banat would be ripe for the taking. If Brusilov and his Russians succeeded in crossing the Carpathians, they would be the most likely to acquire the desired provinces, a situation too dangerous for the Romanians to contemplate.

In August, therefore, the Romanians went back to the Allies with a new proposal. If the Allies (including Russia) would guarantee post-war Romanian control of not only Transylvania, but Bukovina and the Banat as well then the Romanians would enter the war. They also demanded that the Russians continue their offensives against the Austro-Hungarians and that the British and French continue the Salonika offensive to pin down the Bulgarian troops fighting there. Most Allied (especially Russian) diplomats thought the price too steep, but they agreed because they were anxious for some good diplomatic news and they hoped a Romanian declaration of war might have a positive effect on other neutral nations, who might be persuaded to enter the war on the Allied side.

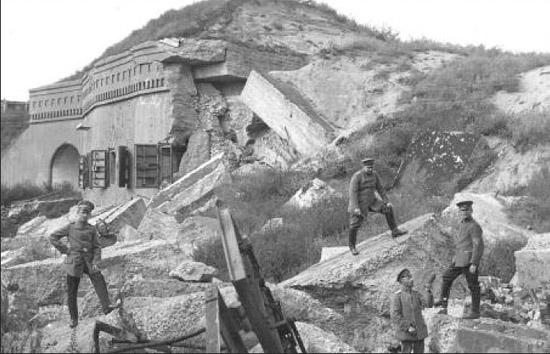

German soldiers pose at the Romanian fortress of Turtukai. Sitting on the Danube River, it was a key strongpoint in Romanian defences. Its rapid fall, along with the loss of its 25,000-man garrison, exposed nearby Bucharest to assault by German forces.

At the end of August, Romania declared war on Austria-Hungary with the following justification:

‘All the injustices our brothers thus were made to suffer maintained between our country and the monarchy a continual state of animosity. At the outbreak of the war Austria-Hungary made no effort to ameliorate these conditions. After two years of the war Austria-Hungary showed herself as prompt to sacrifice her peoples as powerless to defend them.

‘The war in which almost the whole of Europe is partaking raises the gravest problems affecting the national development and very existence of the States.

‘Romania, from a desire to hasten the end of the conflict and to safeguard her racial interests, sees herself forced to enter into line by the side of those who are able to assure her realization of her national unity. For these reasons Romania considers herself, from this moment, in a state of war with Austria-Hungary.’

Almost immediately, Romanian forces crossed into a lightly defended Transylvania with the aim of seizing it before the Russians did so. The war had been extended to yet another country, once again with disastrous consequences.

EXIT ROMANIA

The Romanians had been careful not to declare war on Germany, a country with which they had no direct quarrel of any kind. The distinction failed to make an impression on Kaiser Wilhelm, who exploded in rage. He saw the Romanian declaration of war as a family betrayal and a reneging on an alliance commitment. He immediately ordered Germany to declare war on Romania and made clear his desire that it be erased from the map as quickly as possible. The Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria, both of which nursed grievances against the Romanians from the Balkan Wars, eagerly followed Germany’s lead.

Hindenburg decided on a swift and punitive expedition against the Romanians. He formed two large Central Powers armies, each featuring a combination of German, Austro-Hungarian, Bulgarian and Ottoman troops and placed them under German control. One of the armies was given to the ruthless and battle-hardened Erich von Falkenhayn, fresh from his dismissal after his failure to take Verdun. Anxious to restore his reputation and prove his worth, he seethed with the chance to execute the Kaiser’s orders. The other army went to August von Mackensen, one of the architects of the Gorlice-Tarnow breakthrough. Romania was about to face a double pincer movement led by two of the most efficient and merciless generals the Germans had.

Without Turtukai to guard it, the Romanian capital of Bucharest fell. Residents of the city felt the full weight of German fury, with some senior Germans arguing that the Reich should annex the city directly in order to exploit it more fully.

Until these forces could assemble, the Romanians enjoyed considerable success. They ranged 80km (50 miles) deep into Transylvania with more than 350,000 men against the barely 30,000 men the Austro-Hungarians could muster to stop them. It soon became obvious, however, that the Central Powers response would be much stronger than the Romanians were prepared to handle. Like a schoolyard bully who had angered one too many classmates, the Romanians looked around for help. They naturally turned to the biggest kid on the block, the Russians. Alexeev refused to send any help at all, accusing the Romanians of acting like vultures only interested in carving up the Hungarian corpse after the Russians had fought and died for it.

The 10cm M1917 gun was specifically designed to destroy enemy artillery pieces, a tactic known as counterbattery fire. The gun proved very effective in German hands and remained in use well into World War II.

By early September, Falkenhayn was ready to use what he learned at Verdun and elsewhere against the Romanians. His Ninth Army would clear Transylvania and enter Romania from the west, slicing southeast through the Ploesti oil fields and toward Bucharest. At the same time, Mackensen’s Army of the Danube would invade from the south, using Bulgaria as its base, and overrun Romania’s border fortifications. It would then advance northeast into the Dobrwa region, seizing the Black Sea ports as it went. The only help the Romanians could expect was from the Allied units in Salonika, but they would have to cut through the Germans and Bulgarians opposite them to have any effect at all. As it turned out, the demoralized Salonika garrison was barely able to fight off the mosquitoes, let alone the Germans.

A cool professional in the Prussian tradition, Falkenhayn had come to the Kaiser’s attention as a result of his ruthless actions in China to protect German interests during the Boxer Rebellion. He had become a court favourite, and had done well in all the tasks assigned to him in the years before the war. He replaced Helmuth von Moltke in charge of German forces at the end of 1914 and, as a committed westerner, had launched the bloody Battle of Verdun early in 1916. Ironically, the westerner was sent east to dispatch the Romanians, a job he took on with great energy. He was a ruthless general who advocated the bombardment of civilians from the air, unrestricted submarine warfare, and the use of poison gas.

On 5 September, Mackensen began his concentrations against Romania’s most powerful fortress complex, Turtukai. It boasted 15 separate fortifications and, in a fit of hubris, its commander promised that it would become the east’s Verdun and hold up any and all German attempts to take it. Made up mostly of earthworks instead of the steel and concrete of Verdun’s Forts Douaumont, Souville and Vaux, Turtukai was no match at all for the powerful German siege guns. Within 24 hours of the first German shell hitting it, the commander surrendered along with the majority of his garrison of 39,000 men. The fortress of Silistria followed in due course, leaving Mackensen free to begin his movements on schedule.

At the end of the month, Falkenhayn began his movements as well. It took him just a few days to clear the only important strongpoint opposite him, the fortress of Hermannstadt (built with German money and German technical help) and capture its garrison. He then began to push the Romanians back out of Transylvania and against the city of Kronstadt. Only rainy weather and their own extended supply lines slowed the German pursuit. Seeing the desperation, a Russian detachment finally came to the aid of the Romanians, but when they arrived on the battlefield, the Romanians mistook them for Bulgarians and surrendered. The Russians responded by pillaging and looting whatever they could find before withdrawing back into Russia.

In November, Mackensen’s men crossed the Danube in pontoon boats. At roughly the same time, Falkenhayn’s men crossed the 1830m (6000ft) peaks of the Transylvanian Alps just before the first snows began to close the passes. There were now no natural barriers between the Central Powers forces and Bucharest. Supplies began to run low, but all concerned could see that the campaign was fast coming to an end. The British looked on in horror but could do little to help, though they did send a commando team into the Ploesti oil fields, which destroyed 800,000 tonnes of oil and petrol to prevent them falling into German hands.

The Allies did what they could to help Romania, but to no avail. The ensuing Treaty of Bucharest made Romania a vassal state to Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria, which took most of Romania’s precious mineral resources and grain supplies.

The French sent Henri Berthelot, a veteran of the Marne, to try to direct a Romanian counterattack. It was hopeless. Six entire divisions of the Romanian Army had disintegrated so badly that for all intents and purposes they no longer existed. Only 90,000 soldiers remained of the 700,000-man Romanian Army. The army had also lost almost 300,000 rifles, 350 machine guns and an equal number of artillery pieces. On 25 November, the Romanian Government left Bucharest and headed north to Jassy. Four days later Mackensen entered the city, effectively ending the Romanian campaign and forcing the Russians to move divisions to cover their previously undefended border with Romania.

The Kaiser’s generals had delivered on their promises. The Central Powers added Bucharest to the list of key cities they occupied along with Belgrade, Brussels and Warsaw. Like those other cities, Bucharest and the rest of Romania soon faced the full fury of German occupation. Hindenburg and Ludendorff argued for annexing Romania to Germany in order to execute the fullest possible exploitation of its mineral and agricultural resources. The Kaiser at first agreed, but his vengeance was soon counterbalanced by diplomats in the Foreign Ministry who argued that annexation would send the wrong message to other neutral nations.

The diplomats, however, could not keep the generals from enforcing a crushing armistice on the defeated Romanians. The Germans took more than one million tonnes of oil, two million tonnes of grain, 300,000 animals and 200,000 tonnes of wood out of Romania, reducing the country to starvation conditions. The Treaty of Bucharest codified these harsh measures, giving the Germans a 90-year lease on all Romanian oil wells and mineral mines. Romania also lost all of its mountain passes and most of its Black Sea coastline, although the Germans were politic enough to grant the former to Austria-Hungary and the latter to Bulgaria. The Danube River delta fell under the authority of a joint Central Powers commission and Bulgaria took back the Dobruja region it had lost to Romania in the Second Balkan War in 1913. Romania had paid dearly for its ill advised decision to enter the war and served as a reminder to the French, British and Russians of the need to keep fighting in 1917 or risk the same fate.

‘The remembrance I keep of those days is of a suffering so great that it almost blinded me; I was as one wandering in fearful darkness wondering how much anguish one single heart can hear.’

Romanian Queen Marie remembers the German Invasion

The outmatched Romanian Army suffered enormous casualties at the hands of the much more experienced Germans. The Romanians nevertheless did well at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, gaining the territories of Bessarabia, Bukovina and Transylvania.