Russian soldiers in Petrograd. Their relaxed demeanour evokes the decline in discipline among Russian soldiers by 1917. The presence of thousands of armed men near major cities added to the tension inside Russia.

The failures of the Russian system in 1914 and 1915 underscored the fundamental weaknesses of the Tsarist state. The 1916 Brusilov Offensive's success fell far short of reversing Russia’s battlefield fortunes. Russia’s sufferings led to increasingly strident demands for change. By 1917 those calls had become irresistible and Russia underwent two revolutions.

In hindsight, it is easy to see that the Brusilov Offensive was Russia’s last real chance to emerge from the war victorious. The Russians had more than redeemed themselves from the disasters of Gorlice-Tarnow, Lemberg and Warsaw in 1915 and had made one of the war’s most impressive territorial gains. They could at last point with pride to a military accomplishment that had changed the very character of the war. Russian liaison officers in London and Paris could make favourable comparisons between the Brusilov Offensive and the bloody frustrations that the British and French forces had faced at almost the same time on the Somme.

The Russian Parliament or Duma photographed in session. The Duma was much weaker than its British and French parliamentary counterparts, its lack of independence symbolized by the giant portrait of Nicholas II that hangs over the Speaker’s rostrum.

But even so massive and crushing a campaign had failed to put the Russians in any kind of place to dictate favourable peace terms to their enemies. Instead, despite the ground and momentum gained, the offensive had inflicted heavy losses and had laid bare the essential flaws in the Russian command system. The Russians had proved themselves to be slow and inefficient at the very moment when a much larger victory might have been at hand. A few prescient observers (Brusilov among them) understood that the ground gained could not be held indefinitely and that Russia was in all likelihood incapable of conducting another such offensive in the near future. Even if it could, the result would probably be the same: a few kilometres of strategically insignificant steppe recovered for high losses.

A workers’ demonstration featuring caricatures of Rasputin, the influential monk, and Alexander Protopopov, a court favourite and syphilitic who had become Minister of the Interior. Both men were accused of using their influence against the Russian people.

THE STRATEGIC SITUATION

The Brusilov Offensive notwithstanding, from the perspective of the winter 1916/17, the outcome of the war was still very much in doubt. For the Germans, crushing the Romanians had been easy enough and had provided a kind of cathartic release following the frustrations they had experienced at Verdun and on the Somme. Still, the Romanian campaign had absorbed resources that might have been better employed elsewhere. More fundamentally, Germany still faced its dreaded two-front dilemma and both of its principal allies were showing serious signs of cracking.

The Brusilov Offensive had all but ended the Austro-Hungarian Army’s ability to do anything more complex than static defence, and in the Middle East, the Arab Revolt and a renewed British interest in Palestine had marked the Ottoman Empire as a primary target for 1917. Germany would need to conduct offensives in the coming year to help both allies or risk their being vanquished.

Inside German circles, the mood was therefore hardly optimistic, despite the continued bombast that came from the Kaiser. He presented unrealistic schemes for fomenting a German-backed Muslim revolt in India and for arming the Japanese in return for their attacking the American possessions in the Philippines. Knowledgeable officers in the Germany Army simply shook their heads and took steps to cut the Kaiser further and further out of the decision-making loop. Germany was becoming more and more a military dictatorship every day, with the generals setting not just military policy, but economic and diplomatic policy as well. Their war aims grew more and more ambitious, both cutting off any possibility of a negotiated settlement and committing Germany to fighting harder and longer.

The most fundamental problem the Germans faced was on the high seas where the British blockade continued to cut into the food supplies for both the army and the home front. Expecting a short war in 1914, the Germans had not made anything like adequate preparations for feeding civilians during a prolonged war. The German Navy had tried to take over control of the North Sea in the summer of 1916, but the fleet had been chased back to its ports after the inconclusive Battle of Jutland. The Germans had inflicted more damage than they had taken, but they had also learned that the British fleet was too large and powerful for the Germans to ever hope to attain mastery of the high seas. The German surface fleet never engaged the British again.

Introduced by the Germans in 1915, the Bergmann MG15 Na machine gun was designed to be light and manoeuvrable. Its air-cooled barrel tended to overheat and it had limited range, but it proved to be adequate in most conditions.

After Jutland, the only way to deal with the blockade was to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, a course that risked bringing the United States and its immense economic assets into the war on the Allied side. Falkenhayn and most senior admirals dismissed the power and potential of the Americans and urged the Kaiser to unleash the U-boats. Advocates of unrestricted submarine warfare argued that the U-boats could starve the British into submission well before the Americans could mobilize their assets for the war in Europe. Submarines, they believed, would sink American transport ships in any case, thereby destroying the nascent American Army before it even fired a shot.

By April 1917, the Kaiser had come to the conclusion that submarines were the only way out of Germany’s dilemma. The Germans had already taken almost everything they could out of Belgium and the parts of France and Poland they occupied, reducing the local populations to near starvation conditions. They would do the same to Romania and later to the Ukraine as well. But seizing food created tremendous animosities and absorbed needed resources. As a long term policy it was doomed to fail, as peasants responded by hoarding more of their grain or refusing to plant crops they believed would just be taken from them anyway. Like most of his advisers, the Kaiser assumed, with a breathtaking insouciance, that the Germans would win the war long before the Americans could do anything to stop them. Therefore, there was no reason to let the possible American response force the Germans to keep a powerful option off the table.

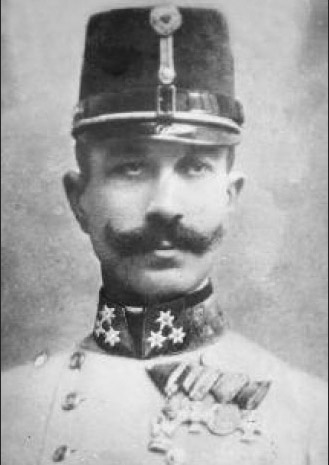

Böhm-Ermolli’s life and career shows the diversity and complexity of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Born in what is now Italy, he served the empire for more than 40 years. When the war ended, he settled into the estate he had purchased while on active service, which sat in the part of the empire that became Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovak Government granted him a reserve army commission and a pension. Later they promoted him to general in the active forces and he remained on service with them until his retirement in 1928. In 1938 his estate, which was in the Sudetenland, was annexed by Hitler’s Germany and he became a German citizen as well as an honorary general in the Wehrmacht reserves. Three years later he died and was afforded a state funeral in Vienna, once the heart of the empire he had served for so long.

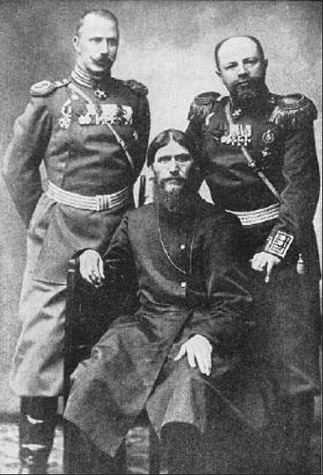

Rasputin (centre) gained influence at the Russian court by claiming that he could cure the haemophilia that afflicted the royal family. The ‘Mad Monk’ was a negative presence at court and in December 1916 he was assassinated.

Russian soldiers gather for a meeting of revolutionaries. Revolutionary ideology, with its promises of peace, had great appeal to many men in uniform. Even many officers saw the lure of revolutionary thinking.

Given all of these risks, a negotiated compromise settlement would have been in the interests of both sides in the east, but neither Germany (which was calling the shots for Austria-Hungary as well) nor Russia expressed any interest in such a solution. The Germans presumed that once they had taken firm control of Austro-Hungarian assets, further setbacks like the Brusilov Offensive would be avoided and a massive offensive could deal the final deathblow to the Russians. For his part, the Tsar had staked the survival of his regime on winning the war when he had assumed supreme command in 1915. At the end of 1916 he dismissed his Prime Minister, a Baltic German who had expressed interest in opening up negotiations with the Germans through a neutral third party. In his place came a Slavophile from the Russian Parliament (the Duma) who had repeatedly depicted the war as a struggle for the very survival of the Russian people. The move was widely seen as a rededication of the Tsarist regime to winning the war at all costs.

The Russians also felt that they needed to resume the offensive to help out their allies. The British and the French had had a miserable 1916. Verdun and the Somme had bled their armies for little gain and, as a result, the French had experienced a major command shake-up. The new French commander, Robert Nivelle, had pledged to resume the offensive in the west, but even the massive Somme offensive had done little to help Russia the year before; therefore few Russians expected much direct help from whatever offensive Nivelle designed for 1917. Instead, Russian generals argued for a new offensive in order to take some heat from the western Allies, who were also their primary sources of credit and hardware.

The western Allies saw the war in just the opposite terms, believing that the Russians would be the first to crack. In a symbolic gesture, the western Allies greeted the arrival of the new Russian Prime Minister with a renewal of their support for Russian control of Constantinople at the war’s end. The move was designed to infuse the Russians with more motivation to keep fighting and to show that the British and French were willing to offer their support, at least in the diplomatic arena. The Russian Government responded with a statement promising to continue the war in order to realize the ‘age-long dream, cherished in the hearts of the Russian people’, of annexing Constantinople.

But the willingness of the Russian Government to continue the fight was not matched in spirit by its people. Inflation was rampant: goods that would have cost 100 roubles at the start of the war cost more than 1100 roubles by the start of 1917. Wages did not rise to keep pace with this inflation; thus whatever food did reach the cities was usually beyond the reach of the average Russian. Transportation difficulties greatly reduced the amount of food available for purchase in the cities in any case. Most opponents of the government lambasted the Tsar, not for his failure to advocate a common-sense compromise peace, but for his inability to prosecute the war more efficiently. Even some generals, including Brusilov, had concluded that the system would need massive, fundamental changes if Russia were to win the war. Russian industry had in fact made some impressive gains and had begun to fill the orders for shells that the War Ministry sent to the factories, but morale was low and the enthusiasm of new recruits for the war was even lower. The mythic notion of pan-Slavism no longer seemed a reasonable justification for continuing the war and all of its suffering, both on the front lines and at home.

An unseasonably cold winter had shown how deeply the war was cutting into Russian life. Food and fuel became increasingly scarce and the rigours of war had so denuded the Russian transportation system that although the 1916 harvest had been generally good, food could not get from the countryside to the cities where it was most needed. The death of the notorious adviser to the Tsarina, the mysterious and (some said) pro-German monk Rasputin, had added a great deal of uncertainty about what exactly was going on at the Russian court. The Tsar’s regular absences from court to be seen closer to the front lines had not helped matters much. His absence from court led to more intrigues and his presence with the armies did little to bolster morale.

‘At one o’clock in the morning [16th] I left Pskov, with a heavy heart because of the things gone through. All around me there is treachery, cowardice and deceit.’

The Tsar’s diary entry on the day of his abdication

Desertion and indiscipline in the Russian Army was matched by revolutionary sentiment on the home front. It became harder and harder for the Russian Government to track and catch the thousands of draft evaders who were wandering the streets and the countryside. Many of them became anti-war agitators urging men to avoid military service or to mutiny. Draft evasion had been a long tradition in Russia and peasants had found many ways over the years to hide their sons from the army.

Revolutionary ideology, influenced heavily by the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, also held great appeal among Russian industrial workers. The men shown here are on strike at a metals factory in Lysva, Perm Province.

In the cities, strikes and protests became more and more common, shutting down production of military hardware and contributing to the general sense of unease. Public discussion of a future without the Tsar became more common. Strikes were the largest problem, because they both threatened the industrial order and were a manifestation of public mistrust in the system. The Duma reconvened in February amid some of the largest and most widespread strikes of the war to date. The Tsar left for a routine trip to his military headquarters at Mogilev on 7 March. The next day another massive wave of strikes began and lasted for three days. Russian troops had been ordered to put the strikes down with force if necessary, but they had refused. A detachment of Cossacks, normally among the most loyal units to the Tsar, had refused to bring their rifles with them into working-class districts of St Petersburg (renamed Petrograd to give it a more Russian-sounding name) and a machine-gun unit disobeyed orders and replaced their live ammunition with blanks. The men of one regiment went even further, shooting their officers and joining the strikers, taking their weapons with them.

The Duma, whose leaders had concluded that the Tsarist system was incapable of dealing with the crisis, formed the Provisional Government and deposed several of the Tsar’s ministers. Nicholas responded by leaving his military headquarters to return to Petrograd and announcing that he would dissolve the Duma once he arrived. He never got the chance to carry out his threat. Strikers had paralyzed the Russian railway system, preventing loyal Russian units from getting into the cities and generally bringing the entire Russian system to a standstill. Strikers had also pulled up the railway line Nicholas was to use to get back to Petrograd, forcing him to go to the town of Pskov on14 March, where railway workers stopped his train and forced him to get out.

Bolshevik ideology was initially most appealing to the urban workers for whom it was designed, but the Bolshevik call for land reform also attracted a wide following from Russian peasants, especially in the western sections of the country, leading to widespread disturbances.

At Pskov, Nicholas re-established contact with his Army chief of staff, Mikhail Alexeev and the Northwest Front commander, Nikolai Ivanov. They presented him with reports of massive indiscipline in the army and widespread unrest on the home front. They then told him that the situation demanded drastic action and urged him to abdicate. They advised him that the Duma would no longer recognize his authority and that his stepping down was the only way to avoid civil war. The Tsar reluctantly agreed and then signed a manifesto to that effect that Duma leaders had already drawn up. He then issued his own statement, abdicating in his name and the name of his son as well. He transferred power to his brother, the Grand Duke Michael, whose marriage to a twice-divorced commoner had put him on bad terms with the court. A group of Duma representatives had foreseen this eventuality and sought out Michael to urge him not to accept the throne.. They told him that no solution other than a full transfer of power from the royal family to the Provisional Government would be acceptable. Michael, who had little desire to rule in any case, agreed. The Romanov dynasty was over with surprising speed and equally surprising loss of life.

In the days of the great struggle against the external enemy, who has striven for nearly three years to enslaveour homeland, the Lord God has willed to subject Russia to yet another heavy trial. The popular disturbances which have broken out threaten to have a calamitous effect on the further conduct of the hard-fought war. The fate of Russia, the honour of our heroic army, the welfare of the people and the whole future of ourbeloved Fatherland demand that the war be brought to a victorious conclusion. The cruel foe exerts his last efforts, and the time is near when our valiant army, together with our glorious allies will decisively overcome him. In these decisive days in Russia’s life, we have deemed it our duty in conscience to our nation to draw closer together and to unite all national forces for the speediest attainment of victory. In agreement with the State Duma we have acknowledged it as beneficial to renounce the throne of the Russian state and lay down Supreme authority. Not wishing to separate ourselves from our beloved son, we hand over our succession to our brother, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and give him our blessing to ascend the throne of the Russian State.We command our brother to conduct the affairs of state in complete and inviolable union with the representatives of the nation in the legislative institutions on such principles as they will establish, and to swear to this an inviolate oath. In the name of our deeply beloved homeland, we call on all true sons of the Fatherland to fulfil their sacred duty to it by obeying the Tsar in the difficult moment of national trials, and to help him, together with the representatives of the people, lead the Russian State to victory, prosperity and glory.May the Lord God help Russia!

Pskov, 2 March 1917

15 hours 5 minutes

Nicholas

The abdication of the Tsar did not necessarily mean the end of Russia’s war. A few anxious days followed, but some measure of calm did return to the cities and the army. Most of the senior officers of the army and navy pledged their allegiance to the Provisional Government; many of those who did not were court favourites of no particular competence in any case. Even Alexeev, the Tsar’s former senior military adviser, obeyed orders from the Duma to place his former master under arrest and transfer him to Tsarskoe Selo before his dispatch to Siberia. In Britain and France, there had been few admirers of the Tsarist system and many hoped that the new government would prove to be more representative and more inspiring to the Russian people. In Paris and London (and on the Western Front as well), people cheered the Provisional Government’s statement that it would continue to fight the war in the name of the Russian people.

The March Revolution solved a major ideological problem for the Allies. Claiming to be fighting a war for the defence of liberty and freedom had always been a shaky rhetorical trick when the largest of the Allied armies was commanded by the most regressive and repressive regime in Europe. With the Tsar gone and a new, plausibly representative, government in place in Russia, however, Allied politicians could more reasonably state that they were fighting a war of democracy against autocracy as the Central Powers comprised three distinctly unrepresentative regimes. Thus could politicians more convincingly sell the continuation of the war in the Allied nations as an essentially defensive war of free people against the aggressive regimes of their autocratic enemies.

Such rhetoric was especially important for the American President, Woodrow Wilson, who led the United States into the war shortly after the Tsar’s abdication. Wilson’s high-minded idealism bewildered many Europeans, but it led him to see great possibilities in the future of a representative Russia. The United States was the first country to recognize the new government on the principle that it had been determined by the will of the Russian people. Wilson’s hopes for what this new Russia could achieve help to explain his anger and disappointment at the later Bolshevik success, and thus his decision to intervene in the Russian Civil War.

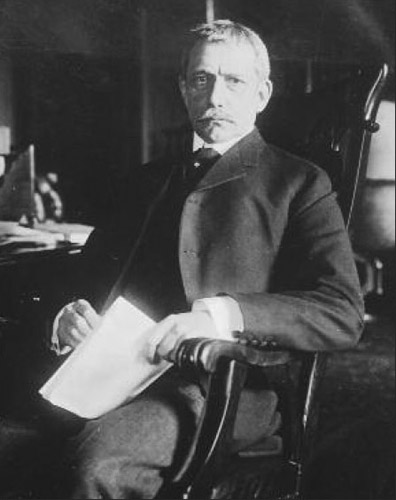

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg was one of a very few German voices arguing for a compromise peace with Russia, although he expected such a peace to be favourable to Germany. He was forced to resign in July 1917.

For their part, the Germans hardly knew what to make of the new situation in the east. Some saw an opportunity to take advantage of the chaos by conducting a quick offensive, although others were cautious about attacking and thereby giving the new Russian nation a cause that might rally them. They advocated playing a waiting game and letting the Russian system collapse in against itself. Most German leaders despised the inefficiency and corruption of the Tsar’s court, but the forced abdication of a monarch by a war-weary and hungry populace boded ill for the future of Germany as well. As food became increasingly scarce in Germany, opposition to the Kaiser had grown, although it had not reached anywhere near the level of Russia. Still, the similarities did not go unnoticed. The German Chancellor, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, gave a speech shortly after the Tsar’s abdication in which he said, ‘Woe to the statesman who does not recognize the signs of the times and who, after this catastrophe, the like of which the world has never seen, believes that he can take up his work at the same point at which it was interrupted.’ The speech was widely interpreted as a call for democratic reforms in Germany after the war to forestall the possibility of a similar revolution in Berlin.

Tsar Nicholas II (seen standing, centre right, with spade) was one of the world’s most powerful men in 1914. Three years of war later he was a prisoner under house arrest and forced to tend a garden, a symbol of the powerful and rapid changes the war had brought to Russia.

Removing the Tsar was one thing. Finding a government that could replace the Tsar’s and compel the loyalty of the Russian people was quite another. The new Provisional Government was headed by a Russian prince, Georgi Lvov, a political moderate who had been among the first aristocrats to advocate the Tsar’s abdication. His participation in the government helped convince many members of the middle class to support it in the hope of Russia gaining liberal reforms and a basic statement of rights. The most important member of the new government, however, was Alexander Kerensky, a lawyer and a moderate socialist. A powerful public speaker with support from urban industrial workers, he had used his seat in the Duma to oppose Russian entry into the war in 1914 and then became a vocal critic of the Tsar. Illness had forced him to go to Finland for treatment during parts of 1915 and 1916. From there he observed the changes inside Russia and had reversed his stance on the war, concluding that Russia’s participation was necessary and just in order to combat German militarism. But he had also concluded that the Tsar’s mismanagement of the war risked disaster, not just for Russia but for all of Europe. Russia therefore had an obligation to continue the war, but the nation had to find ways to fight it more effectively.

Upon joining the Provisional Government, Kerensky began to give patriotic speeches in which he urged Russians to continue the war, but as a way of safeguarding their own newly won liberty, not for the maintenance of the repressive regime of the Tsar. In his capacity as Minister of War, he gave Brusilov command of the Russian armies and began a massive reorganization of Russian industry. He also oversaw the extension of some basic civil rights to Russians and built links to the voice of many members of the working class, who agreed to work with him even though many of them did not support a continuation of the war. Before long the young and energetic Kerensky had eclipsed Prince Lvov as the key figure of the provisional government.

The Austrian Steyr Model 1917 pistol carried a 9mm round. It is most commonly associated with Austrian units, although the Steyr was also used by Bavarians and several units of German stormtroopers on the Western Front.

As one contemporary had observed, the changes in Russia had been so revolutionary (and, in most people’s eyes, so positive) that ‘men looked for other miracles to follow’. Among those anticipated miracles was a change in Russia’s military fortunes. Kerensky reiterated Russia’s commitment not to make a separate peace with the Germans, and Britain and France soon followed suit with a declaration that they would not sign a separate peace either. High-level representatives like France’s well respected socialist Minister of Munitions, Albert Thomas, and America’s Elihu Root (a former Secretary of War, senator and a Nobel Laureate) came to Russia with diplomatic delegations to offer their support and express their joy at having a democratic Russia on their side. Root told Kerensky that the Revolution had brought ‘universal satisfaction and joy’ to the American people and that Russia had to win the war because ‘the triumph of German arms would mean the end of Russian liberty’. The internationally respected Root became Wilson’s senior representative in Russia, a symbol of how important the new relationship was in American eyes.

The idea of harnessing all of this positive energy into another military offensive seems to have come first from Alexeev, who, despite his close links to the Tsar, had remained an important adviser to the Provisional Government. Kerensky was careful to follow proper channels and insisted that the Duma, the people’s representative, be made a full part of the military process. The government formally presented the idea of an offensive to a secret session of the Duma in mid-June. Among the goals the government laid out for the offensive were forestalling revolution at home by showing the competence of the Provisional Government to handle military matters, bolstering Russia’s place in the post-war peace conference, and proving Russia’s value to its alliance partners. The Duma passed a resolution approving the idea and declaring peace ‘or prolonged inactivity on the battlefront’ to be an act ‘of ignoble treason … for which future generations never would pardon the Russia of the present day’. Shortly thereafter the Congress of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Delegates voted their support for the idea and their confidence in the Provisional Government. The news served to boost morale in the trenches and put a temporary brake on the waves of strikes. Brusilov and others were welcomed at the front with ecstatic receptions. Russia seemed to have come back from the brink.

Franz Joseph, who had sat on the Austro-Hungarian throne since 1848, died in November 1916. He was succeeded by his grandnephew, who became Emperor Karl. A cavalry officer by training, Karl had served in avariety of military assignments. Influenced by his pro-Allied wife, he came to the throne anxious to end Austria-Hungary’s participation in a war that he knew would eventually disintegrate his empire. He sent outsecret peace feelers to the French, but his refusal to cede Austro-Hungarian territory ended this initiative. The Germans, however, found out about his overtures and never trusted him again. Throughout 1918 he continued to plan for the transformation of Austria-Hungary into a federation with himself still at thehead, but few of his former subjects were interested in hearing what he had to say.When the war ended, he fled first to Switzerland then to Spain, where he died virtually penniless of pneumonia in 1922 aged 34.

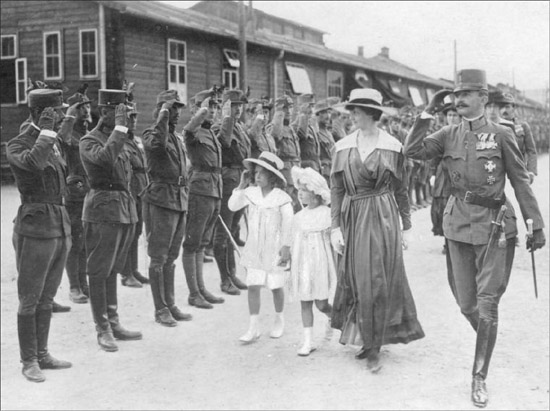

Emperor Karl I took over the Austro-Hungarian throne upon the death of his grand-uncle in November, 1916. Finding himself and his empire in a hopeless situation, he sought a separate peace, but got little but German anger in exchange for his efforts.

In the enthusiasm that accompanied the heady days of spring, the Russians had decided to take the field. That enthusiasm, however, made for hasty planning and unclear purposes. Within two short weeks of the Duma approving the offensive, Russian troops were to launch a major attack on the Germans and Austro-Hungarians. There was little time to see to all of the myriad details that necessarily have to accompany a major offensive. Moreover, the ultimate operational goals were unclear. In short, no one knew quite what the offensive was supposed to accomplish other than showing the will of the Russian people to continue the war. In lieu of planning and preparation, the Russians hoped that the new revolutionary ardour of their people would carry the day much as the French revolutionary armies had done at the watershed Battle of Valmy in 1792.

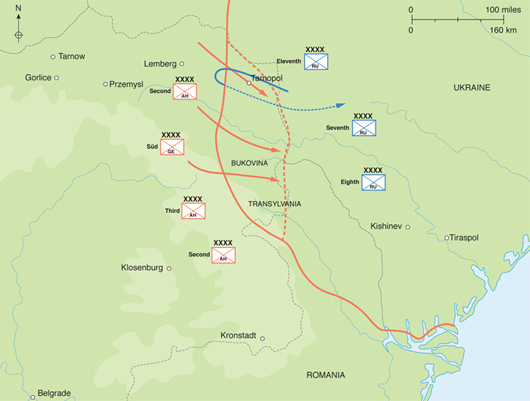

Brusilov set out to plan the offensive, but even he recognized that the government had made inadequate preparations and really had no clear idea of what it wanted. He nevertheless assembled 31 divisions and prepared them for a major campaign as best he could in the limited amount of time available to him. Brusilov concentrated his forces in the south against the Austro-Hungarians. He aimed for the sector held by the Second and Third armies. They guarded the approaches to strategically important oil fields in the Drohobycz area and, beyond them, the symbolic fortress of Lemberg, whose recapture might provide the Provisional Government with the important morale boost it sought.

Elihu Root won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1912 and served as American Secretary of War before serving in the US Senate. He accepted Woodrow Wilson’s offer to become head of a special diplomatic mission to Russia in 1917.

Brusilov and others were worried about the influence of radical propaganda from groups such as the Bolsheviks, which had begun to influence the views of many enlisted men and even many officers. The Bolsheviks argued for an end to the war, which they claimed was a capitalist imperial struggle that had nothing to do with the interests of the average Russian. Their influence was so pervasive that many commanders were afraid that their men would not obey orders, or, worse yet, might turn their rifles on their own officers and mutiny.

The offensive was therefore certainly not without its serious risks. In his fiery oratory, Kerensky had linked the future of the Provisional Government to the success of the Russian military. As war minister, he had also linked his own personal future to the performance of the upcoming offensive. Although most of the political factions inside Russia had offered their support to the attack, the signs were not all positive. The Russians had launched a ‘Liberty Loan’ with great fanfare to help fund the war in 1917. The Russian finance minister hoped that the loan would show the public’s faith in the war and the government, as well as leave Russia far less dependent on foreign creditors. The loan, however, was a failure. Russian workers had too little money to contribute, and most members of the middle class had no faith that they would get their money back or that inflation would not far exceed the promised returns.

Finding money overseas proved to be a problem as well. The Americans were willing to extend credits, but the Provisional Government decided to turn to the British and French they already had business dealings rather than open discussions with Americans with whom they did not. Bankers and diplomats in London and Paris made grand promises but the money did not show up, leaving the Russians with little credit and even less hard currency.

The German-built Aviatik C.Ia biplane entered service in 1915. It was an improvement over an earlier model which had the observer seated in front. This version put the observer in the back, which afforded him better vision and fields of fire.

Without money, the Russians could not solve their munitions shortfalls. The ripple effects of the strikes were still being felt across Russian industry, creating dangerous shortages of all kinds of military hardware. Without overseas credit, the Russians could not buy munitions from the British and the French, the only countries that could possibly have met their orders. Facing uncertain futures of their own, the British and French were understandably reluctant about committing too much to the Russians. The Americans and the Japanese might have filled at least some orders, but neither had fully converted their industrial plants from civilian to military production, and both wanted to see most of their money up front something the Russians struggled to provide.

Morale had improved, but many commanders still reported rampant acts of indiscipline and fraternization with the enemy. Members of ethnic minorities like the Ukrainians often refused orders until their homelands were given more local autonomy by the Provisional Government. Kerensky responded to the morale problem by announcing the reimposition of the death penalty, a move designed to bolster morale by cracking down on dissenters. Instead, soldiers read it as a return to the indiscriminate punishment and brutality of the Tsar’s regime. Rather than raise the fighting spirit of the Russian Army as expected, the decision caused a sharp drop in morale.

The first Russian Revolution was a great boon to American President Woodrow Wilson. With the Tsar gone, Wilson could, at least for a time, claim that the war was one of democracy versus autocracy and despotism.

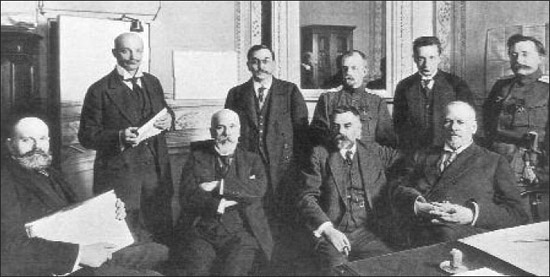

Influential members of the Russian Duma meet in May 1917 to try to form a new government. Alexander Kerensky is second from the right in the back row. Prince Lvov is seated second from the right in the front row. Their decision to continue with the war effort was very unpopular.

Across the front lines, the Austro-Hungarians were hardly in better shape. Most units were well below their allotted strength, short on weapons, and in a fragile state of morale. Those units opposite Brusilov were commanded by Eduard Böhm-Ermolli, whose military career had thus far seen a great deal of ups and downs. The son of a legendary soldier who had risen from the enlisted ranks to general’s rank and a noble title, in 1914 Böhm-Ermolli had been the commander of the Austro-Hungarian Second Army that had spent the early part of the war shuffling back and forth to no effective purpose. His units later moved to Galicia where he had the honour of leading the recapture of Lemberg from the Russians. The retaking of Lemberg had been the high point of his career and had led to his promotion to command of an army group. Brusilov had routed this army group in June 1916, temporarily eclipsing Böhm-Ermolli’s star. By 1917, however, he had not only recovered his command, but had managed to convince the German officers in his army group to follow his general operational guidance. He therefore had much more freedom of action from the Germans than did most of his peers.

Böhm-Ermolli’s army group was to be the target for Brusilov once again. On 1 July 1917, the Russians attacked using most of the same methods that had worked so well for the Brusilov Offensive the previous year. Brusilov had packed his artillery and the bulk of his most reliable infantry into a 48km (30-mile) wide zone that would encompass the main axis of the attack. Subsidiary and diversionary attacks extended the range of the battle to the same length as the front, almost 160km (100 miles) long. Kerensky himself came to the front line to oversee the start of the offensive. For four days he toured Russian front-line positions, talking to the men and urging them to fight for Russia and for their own freedom. He personally gave the order to start the offensive from the Russian front trench line.

‘Natural love of law and order and capacity for local self-government have been demonstrated every day since the revolution.’

Elihu Root’s report on his visit to Russia, June 1917

Kerensky (left) travelled the length of the front line after taking control of the Provisional Government. He hoped to use his oratorical skills to rally Russian soldiers and urge them to continue the war.

Kerensky moved along the line, urging the men on and putting heart into some of the army’s least willing units. When one regiment refused to advance, Kerensky stood on the trench line in plain view of the Austro-Hungarians and told the men that if they would not attack, he would fight the enemy alone. The speech inspired the men (one observer said the men were ‘reborn’) and they went over the top, with many soldiers pausing to embrace Kerensky before they did so. Kerensky was swept away by the emotion and tried to join the attack, but was dissuaded from doing so by the very men he had just inspired to risk their lives. A journalist who saw the scene said it ‘promised to go on record as one of the historic feats in war operations’. Word of Kerensky’s behaviour at the front reached Petrograd where a jubilant crowd gathered outside his home and, not knowing what else to do, began singing ‘La Marseillaise’.

Although there were some exceptions, most soldiers of the Russian Army showed a willingness to fight in the offensive’s early stages. Among the most highly motivated units was a group called the Czech Legion. Its members were ethnic Czechs and Slovaks who had been prisoners of war captured in Russia’s successful campaigns earlier in the war. They were offered the chance of leaving squalid Russian prisoner of war camps in exchange for their service in the Russian Army, and later received a promise from the Provisional Government that Russia would support the formation of an independent Czechoslovakia at the end of the war. The Czech Legion formed two brigades of the Russian Eleventh Army, which became one of Russia’s most dependable large units in the forthcoming offensive.

The last major Russian offensive of the war is known as either the Kerensky Offensive or the Second Brusilov Offensive. By either name it was a complete failure and laid bare Kerensky’s outlook for the future of Russia.

The Eleventh Army and the Seventh Army formed the vanguard of Brusilov’s attack. Brusilov’s old unit, the Eighth Army sat in reserve. Known as the Kerensky Offensive or the Second Brusilov Offensive, it began with great success. Brusilov had placed the Czech Legion opposite the Austro-Hungarian 19th Division, which contained two regiments of ethnic Czechs. These two regiments refused to obey orders to fight against fellow Czechs, and a mutiny soon ensued, sending shock waves back to Vienna. More than 3000 Czechs had simply left the army; some had even joined the Russian attack. The incident was an ominous sign. If ethnic identity had finally superseded imperial loyalty to this extent inside the army, then the empire itself could not have much longer to exist.

I came to you because my strength is at an end. I no longer feel my former courage, nor have my former conviction that we are conscientious citizens, not slaves in revolt. I am sorry I did not die two months ago, when the dream of a new life was growing in the hearts of the Russian people, when I was sure the country could govern itself without the whip.

As affairs are going now, it will be impossible to save the country. Perhaps the time is near when we will have to tell you that we can no longer give you the amount of bread you expect or other supplies on which you have a right to count. The process of the change from slavery to freedom is not going on properly.We have tasted freedom and are slightly intoxicated.What we need is sobriety and discipline.

You could suffer and be silent for ten years, and obey the orders of a hated government. You could even fire upon your own people when commanded to do so. Can you now suffer no longer?We hear it said that we no longer need the front because they are fraternizing there. But are they fraternizing on all the fronts? Are they fraternizing on the French front? No, comrades, if you are going to fraternize, then fraternize everywhere. Are not enemy forces being thrown over on to the Anglo-French front, and is not the Anglo-French advance already stopped? There is no such thing as a ‘Russian front’, there is only one general allied front.

We are marching toward peace and I should not be in the ranks of the Provisional Government if the ending of the war were not the aim of the whole Provisional Government; but if we are going to propose new war aims we must see we are respected by friend as well as by foe.

If the tragedy and desperateness of the situation are not realized by all in our State, if our organization does not work like a machine, then all our dreams of liberty, all our ideals, will be thrown back for decades and maybe will be drowned in blood.

Beware! The time has now come when everyone in the depth of his conscience must reflect where he is going and where he is leading others who were held in ignorance by the old regime and still regard everyprinted word as law. The fate of the country is in your hands, and it is in most extreme danger. History must be able to say of us, ‘They died, but they were never slaves’

The greatest first day success of the offensive came in the capture of a strong point near Brzezany, where Russian forces took more than 10,000 prisoners. The Russians noted with some glee that many of the prisoners were German, not Austro-Hungarian. Böhm-Ermolli’s Second Army collapsed, as did the Eighth Army on its flank. Austro-Hungarian units began to flee in panic. A gap opened in Austro-Hungarian lines that was 72km (45 miles) long and more than 32km (20 miles) deep. The American major-general Hugh Scott personally witnessed the offensive and saw the Russians break three separate Austro-Hungarian trench lines. He reported that what he saw of the Russian Army led him to believe that it was ‘excellent’ in its use of artillery and in the quality of its officers.

Scott could be forgiven for having such an inflated opinion of the Russian Army. For the first few days of July the Russians did indeed look like they had designed a masterpiece once again. The Russians had advanced to Halicz on the Dniester River, thus giving them command of the southern approaches to Lemberg, about 80km (50 miles) away. Southwest of Halicz, the Russians made their furthest advances of the campaign, establishing bridgeheads across the Lommica River, and in the course of doing so, driving a wedge between the German Army Group South and Böhm-Ermolli’s units. Farther to the south, Russian forces had cleared most of the Bukovina region of enemy forces and advanced once again to the passes of the Carpathian Mountains.

Ethnic Czechs and Slovaks in the Czech Legion, formed from former prisoners of war. In 1918, they tried to get to France via Murmansk and then Vladivostok, but instead became embroiled in the developing war between the Red and White factions inside Russia.

The disintegration of Imperial Russia unleashed nationalist feelings in ethnically non-Russian areas. These Estonians are marching for a federated Estonia after the war. The national issue proved to be one of the most daunting facing the Bolsheviks, whose ideology was ideally non-national.

This advance provided badly needed (if largely unintended) help to the Romanians, who responded by cancelling their signing of the armistice with Germany. It was to be a rash and unwise move that only brought further German vengeance later in the year and harsher terms at the Treaty of Bucharest.

The Romanians, however, believed that the Russian advance had changed the situation in the east. And indeed it had. In the first two weeks of July, the Russians reported that they had captured 36,634 enemy soldiers, 93 artillery pieces and 406 machine guns. The Central Powers had been forced to cede two important river lines and the Russians had cut all but one road leading to Lemberg.

Russia also received a new hero in Lavr Kornilov, a man already well known in the army, whose units advanced furthest and with the most success in July 1917. Having served the Tsar in a variety of positions around Asia, he received command of a division in 1914. He was among the Russian officers captured at Przemysl, but he had made a daring escape from his captors and the story had gained much in the telling over the months. He was returned to service as a corps commander and later was placed in charge of the military district of Petrograd. In charge of that city’s defences, he had repeatedly urged the provisional government to use lethal force to put down demonstrations. Although his urgings and his advocacy of the return of the monarchy made him extremely unpopular among the industrial classes of Russia, he was sent to the front to serve under Brusilov, where he had performed well during the earlier offensive.

Lavr Kornilov (left) came from a long line of Central Asian Cossacks.His intrigues in favour of the return of the Tsarist system helped put in motion the events that led to the October Revolution, which in turn resulted in eventual victory for the Bolsheviks.

On 19 July, however, German Army Group South counterattacked and, using nine German and two Austro-Hungarian divisions, crashed into the northern flank of the Russian advance. Low on supplies and fully unable to withstand the assault, the Russians began to flee, often in panic. A tired and physically ill Brusilov ordered a retreat that in many places turned into a rout. Kornilov and Brusilov had furious arguments about the future conduct of the campaign that did not help matters. Within a few weeks the Russians had lost all that they had gained and more. In the final weeks of July, the Russians lost more than 40,000 men to the Central Powers’ losses of just 12,500 men. Central Powers’ forces only stopped their pursuit when they ran out of supplies. On 1 August, Kerensky saw no choice but to remove Brusilov from command and replace him with the only soldier in the Russian Army who had proved his ability to fight, the volatile monarchist Kornilov. He soon made rampant use of the death penalty for soldiers who had deserted or fled in battle, but the policy failed to stem the precipitous drop in morale.

Eduard Freiherr von Böhm-Ermolli was born in Italy to a recently ennobled ethnic German military family and rose quickly through the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian Army. His Second Army was the target of the Kerensky Offensive.

The collapse of the offensive destroyed whatever momentum and confidence the Provisional Government had built. The moderate, centrist position it had occupied soon withered away. On the left the Bolsheviks, with their call for ‘peace, bread and land’, began to attract more and more followers. On the right, calls for the return of the Tsar or another member of the royal family also began to grow shriller. Kornilov himself repeatedly made statements critical of the Provisional Government. The army he now led was in tatters and grew less and less able to defend Russia every day. The high revolutionary spirits of 1 July were gone, their hopes dashed. Men deserted the army in droves, either to escape further bloodshed or to defend their homes from the civil war that many now feared.

I have outlined a few theses which I shall supply with some commentaries. I could not, because of the lack of time, present a thorough, systematic report. The basic question is our attitude towards the war. The basic things confronting you as you read about Russia or observe conditions here are the triumph of the traitors to Socialism, the deception of the masses by the bourgeoisie.…The new government, like the preceding one, is imperialistic, despite the promise of a republic – it is imperialistic through and through.

One

In our attitude toward the war not the slightest concession must be made to ‘revolutionary defence’, for under the new government of [Prince Georgi] Lvov and company, owing to the capitalist nature of this government, the war on Russia’s part remains a predatory imperialist war.

In view of the undoubted honesty of the mass of rank and file representatives of revolutionary defence who accept the war only as a necessity and not as a means of conquest, in view of their being deceived by the bourgeoisie, it is necessary most thoroughly, persistently, patiently to explain to them their error, to explain the inseparable connection between capital and the imperialist war, to prove that without the overthrow of capital it is impossible to conclude the war with a really democratic, non-oppressive peace.

This view is to be widely propagated among the army units in the field.

Two

The peculiarity of the present situation in Russia is that it represents a transition from the first stage of the revolution – which, because of the inadequate organization and insufficient class-consciousness of the proletariat, led to the assumption of power by the bourgeoisie – to its second stage which is to place power in the hands of the proletariat and the poorest strata of the peasantry.

This peculiar situation demands of us an ability to adapt ourselves to the specific conditions of party work amidst vast masses of the proletariat just wakened to political life.

Amid this tense environment, Kornilov’s political intrigues grew. He had determined that the Provisional Government had no right to govern because it had lost the faith of the Russian people, thereby defeating its own democratic logic. In late August, he ordered a Russian army to march to Petrograd and called upon the Provisional Government to hand power over to the army and resign. Kerensky understood that Kornilov’s demands amounted to a virtual coup that would place all power in the hands of a dangerous monarchist. Acceding to Kornilov meant rolling back all of Russia’s gains since March. More seriously, there were signs that the Germans were preparing to launch an offensive in the Baltic provinces and Kerensky needed to know that he had an army commander upon whom he could rely. Accordingly, Kerensky removed Kornilov from command and ordered him to come back to Petrograd. Kornilov refused, setting in motion the events that would lead to the second Russian Revolution. This time, the results would be far more fundamental and have far more dramatic outcomes for the course of the war.