German stormtroopers advance on the Eastern Front. Although many armies had worked on the idea, the Germans were the first to put all of the tactical elements of the system into one operational plan.

By 1917 the external and internal pressures on the Tsarist state led to its collapse and the introduction of the Provisional Government headed by Alexander Kerensky. That state, too, proved unable to deal with the myriad problems Russia faced. By the end of the year, the Bolsheviks had taken power, with grave consequences for the other great powers.

The Germans moved quickly to take advantage of the chaos and confusion inside Russia after the failure of the Kerensky Offensive. They sensed that the Russians were at a crucial material and morale breaking point, and they wanted to place as much pressure on that breaking point as they possibly could. They chose to attack at the port city of Riga, the centre of a multi-ethnic region known to have large numbers of people who were openly hostile to the Russians. They included a sizeable population of Baltic Germans and Finns who had given up any lasting associations they felt towards either the Tsarist system or the provisional government that replaced it. Riga also had great strategic value, sitting just 320km (200 miles) from Petrograd, at once the centre of Russian decision making and anti-governmental revolutionary activity.

Marked early on in his career as an intelligent and hard-working young officer, Hutier’s connections inside the army included such key figures as Erich Ludendorff (a cousin) and Paul von Hindenburg (a former instructor). Hutier made his name on the Eastern Front, where he was one of the principal innovators of infiltration tactics. Although many of the central ideas he used were in fact British or French, Hutier was the first to make large-scale practical use of infiltration tactics. Later becoming known as ‘stormtroop’ tactics, they temporarily restored mobility to the static conditions of the war. Used at Riga on the Eastern Front and at Caporetto on the Italian Front, Hutier’s tactics seemed to have unlocked the secret of winning of the war. Hutier was sent to the Western Front, where he oversaw the implementation of his system in time for the great Spring Offensives of 1918. Like his cousin, he became a key proponent of the stab-in-the-back myth and a supporter of the Nazis before his death in 1934.

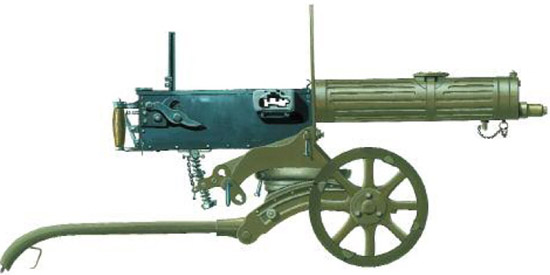

A Russian version of the Maxim MG1910 machine gun. Note the cumbersome jacket around the barrel for water cooling. Many versions came with a wide mouth at the top to allow soldiers to use snow in place of water.

The responsibility for the attack on Riga fell to Oskar von Hutier, the new commander of the German Eighth Army. Once a large conventional army that had won the great victories at .Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, the Eighth Army had recently begun to adopt new tactics, sometimes called ‘Hutier’ tactics, although Hutier himself played little to no role in their origins. Also called stormtroop tactics, the basic ideas were mostly French and British. By late 1917, however, the British and the French had come to the quite reasonable conclusion that with the entry of the United States into the war on their side, they did not need tactical innovation. Rather, their best chance to win the war was to await the incorporation of American men and resources, then conduct a series of large set-piece campaigns in 1918 and 1919 with fresh men and large numbers of heavy weapons.

Not so the Germans, who were still haunted by the two-front dilemma and also knew that they could not hope to match the men and material of the Allies. They also knew that they could not afford to fight many more set-piece battles like Verdun or the Somme and, more importantly, that until they could eliminate one of their two fronts time was not on their side.The arrival of the Americans would make these problems all the more acute. A way therefore had to be found to win on one of the two fronts before the Americans could make their presence felt on the battlefield. Despite the disastrous Allied offensives along the Chemin des Dames and near Passchendaele in 1917, the French and the British were not yet ready to break. That meant attacking the seemingly faltering Russians. Nevertheless, although the Russians certainly appeared weak, no one in the German high command knew how many Russian soldiers remained loyal to the regime or if someone like Kornilov might rally the men and resume the offensive. Russia therefore had to be defeated soon and the Eastern Front eliminated as a German operational and strategic concern.

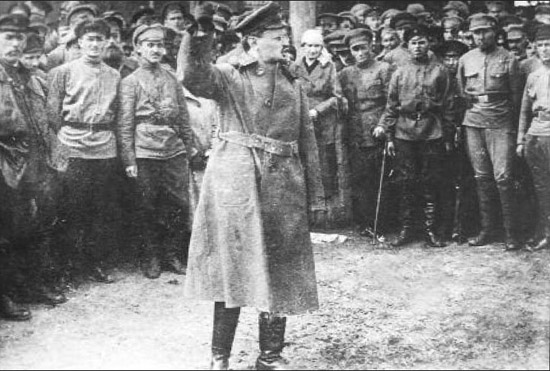

General Oskar von Hutier (left) did not originate the tactics that sometimes carry his name. He was, however, the commander of the first army to use such tactics on a wide scale. His success created a new operational model for the German Army.

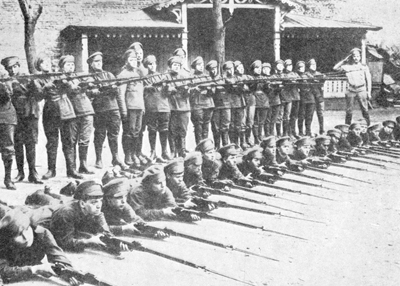

As part of the effort to capture Riga quickly, the Germans decided to take a number of calculated risks. Foremost among them was the introduction of the new ‘Hutier’ tactical system. It involved the use of specialized stormtroops backed by a very careful synchronization of artillery and infantry. The infantrymen were volunteers who agreed to join these special assault detachments in return for extra rations, more leave time and excusal from fatigue duties. They were trained in the use of new and more portable weapons like the light machine guns, portable flamethrower and field mortar. They were also trained to use initiative and think as they moved instead of waiting for orders from their officers.

Hutier tactics were quite complicated and varied considerably from battle to battle, but they shared several features. A stormtroop attack was normally preceded by a carefully designed artillery bombardment that relied heavily on gas instead of high explosive. The gas was targeted at enemy command and control posts with the intention of slowing the enemy commander’s ability to discern the nature of the offensive and his ability to issue rapid orders to meet it. Gas also left the ground relatively undisturbed in order to permit specialized infantry to advance quickly through it.

Those specialized infantry were trained to bypass the enemy’s strongpoints and advance through the holes created by the artillery bombardment. They would then range behind the enemy’s lines looking for enemy command posts, communications infrastructure and any other targets of value. Once the enemy’s ‘head’ had thus been decapitated, the regular German infantry could come forwards to fight its body. Ultimately, the goal of a Hutier operation was to encircle and capture enemy units rather than try to trade casualties man for man, a system that the Germans knew their numbers did not favour.

An attack on Riga in September was to be the first test of the new system. On 1 September 1917, German artillery fired more than 20,000 shells, most of them gas shells, without warning. The attack struck Russian defenders like a bolt of lightning, catching them completely unprepared. German stormtroops soon began to cross the rivers and streams around Riga in specially designed boats, establishing bridgeheads and directing the fire of more conventional artillery to prevent Russian counterattacks. With both banks of a river secured, the Germans could build pontoon bridges for the safe crossing of regular infantry in large numbers. Some of these bridges were even strong enough to allow field artillery to come forward and support the attack.

Using these methods, the Germans were able to land nine divisions of troops across the Dvina River in just 48 hours. Once they did so, the Russian defenders knew the battle was lost and made quick plans to evacuate a now indefensible Riga. Setting some buildings on fire to, the Russians evacuated as many men and supplies as they could amid scenes of chaos and sheer panic. German artillery pounded the city and many of the bridges leading east in the hopes of capturing as many Russian soldiers as possible. By the third day of the operation, German forces had entered parts of Riga, and by day four they had complete control of the city and its port.

The campaigns of 1917 destroyed most of what remained in the Russian arsenal. The Russian Army soon found itself short of almost everything, especially heavy artillery pieces and the shells they fired.

The effect of this battle on both sides was electric. The Germans estimated their casualties at 4200 and Russian casualties at more than 25,000. The Russians also lost 250 of their precious artillery pieces, leaving five Russian divisions without significant artillery support. Many smaller Russian units simply melted away in the face of the attack, underscoring the essential morale problems of the army. The Russian officer corps tried everything it could think of to stem the tide of desertion. Commanders ordered deserters shot on sight, tried to create their own stormtroop detachments and even formed a special all-female battalion. The Russian soldier, however, had begun to give up the cause.

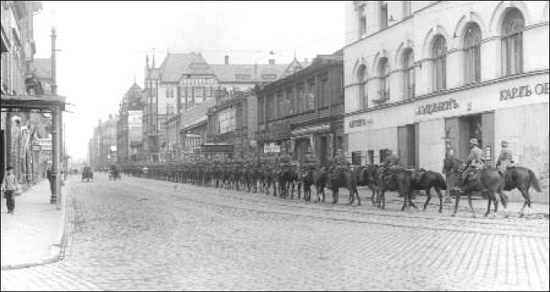

A unit of German cavalry enters Riga, a city with a large Baltic German population. The fall of the city symbolized a major turning point in the war for the Germans and the Russians alike, and set in motion the final end of the Provisional Government.

The Germans rightly saw Riga as a great success and a validation of their investment in the new methods. In stark contrast to the frustrations and indecisiveness of the Western Front, the victory at Riga was dramatic and relatively cheap. The Kaiser decorated Hutier with the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military award, and ordered a day of national celebration, the first since the fall of Bucharest. Hutier then ordered an even more daring amphibious assault to capture the Baltic islands of Ösel, Moon and Dagö. The Germans used aircraft to spot and target enemy positions, torpedo boats and cruisers to clear away the Russian surface fleet from the islands, and marines to secure landing areas. Although there were many problems and much more work clearly needed to be done before the Germans could repeat an attack of this kind, the assault on the Baltic islands represented one of the very few successful amphibious and joint operations of the war and was a crushing morale blow to the Russian Army, which now seemed powerless to stop the German onslaught.

The Germans used methods broadly similar to those used at Riga in Italy later in the year. At Caporetto in late October, they caved in the Italian line and sent two Italian armies retreating in conditions resembling a rout. Only the difficulty of supplying their fast-moving men and the limited goals the Germans had set for the operation kept the disaster from becoming even worse. The new system had now been tested twice, albeit against armies suffering from low morale and poor commanders. Hutier was transferred west with much of his staff to put the new methods in place along the Western Front in preparation for a major last gamble offensive against the British and the French in the spring of 1918 before the Americans could arrive in force.

German troops climb aboard ship on their way to the Russian Baltic island of Ösel as part of an operation code-named ‘Albion’. The Russians saw the attack coming, but could do little to prevent it. German control of the Baltic proved to be decisive.

The tactical lessons of Riga were clear. For the Germans, Riga showed the value of new methods of war that, when well executed, were parsimonious with German lives, but created panic in enemy lines. Thus large victories by a smaller German army against a larger Russian army were still conceivable. This conclusion was welcome to the Germans because they knew that they would soon need to begin large-scale troop transfers from the east to the west to meet the arrival of the Americans. Whether the new methods would work against the French and British as well as they had against the Russians and the Italians, however, remained to be seen.

Nevertheless, alongside the tactical succeses stood the strategic shortcomings that Riga also revealed. The capture of Riga did not materially change the situation in the east as much as the Germans had hoped. The Germans might be able to use Riga’s port to ease some supply problems, but the port would soon ice over, thus limiting its utility. The Germans also expected to receive a warm welcome from the Finns and Baltic Germans living around Riga, but it remained far from clear how much their support would translate into usable military assistance. Like the Poles, the Germans expected the Finns to be grateful for liberating them from the Russians, but they anticipated that few Finns would seek military service in the German Army. Even many Baltic Germans had their doubts about trading a Russian regime that had generally treated them well for a German regime that looked upon them as alien and suspicious, notwithstanding the ethnic links that bound them together.

Most importantly, Moscow and Petrograd were still far away. The Russians had set up a reasonably strong defensive line between Riga and Petrograd and most Germans expected Russian soldiers to fight harder for the latter than they had for the former. Even the capture of Petrograd or Moscow, moreover, provided no sure guarantee that the Russians would leave the war. Nightmarish visions of 1812 still burned deeply into German strategic and operational thinking. Germany had won an important battle (and one the Kaiser thought worth celebrating), but it was far from clear how the Germans might still win the war. No one in Germany welcomed the thought of chasing the Russians to and beyond Moscow as Napoleon had done.

For their part, the generals of the Russian high command intuitively understood the German dilemma. They concluded that the loss of Riga itself was no great calamity for Russia. Many Russians in and out of uniform had seen Riga as a hotbed of Baltic German treason and radical revolutionary sentiment. They therefore responded to its loss with mixed emotions. On the one hand the loss of a key city of the Russian Empire with so little effort expended in its defence was an embarrassment; on the other hand, the city had not done much to help the Russian cause and not a few Russians greeted the news of its fall with a sense of good riddance.

The real importance of the fall of Riga lay in what it meant for the Russian political system. The loss of the city, on top of the failure of the summer offensive, proved to most Russians beyond a doubt that the Kerensky government was little better at fighting wars than the Tsarist system it had replaced. The wild optimism and hope that had accompanied the change of government was quickly replaced by pessimism and fear. Perhaps most importantly, the failure of the Kerensky government meant that the already weak Russian centre could not hold. The fate of Russia would soon turn into a struggle between factions on opposite sides of the Russian political spectrum, with important consequences for the last year of the war.

In May 1917 a Russian peasant woman named Maria Bochkareva convinced Kerensky to allow her to form a 2000-person-strong women’s battalion. Desertions and casualties soon reduced the number to a few hundred, but they made news across the world and helped to shame more Russian men into staying with the army, which many suspected was Kerensky’s goal all along:

‘Among the passengers once standing in a car, I saw an officer of the Women’s Battalion of Death. With a white fur cap saucily perched on her head, her hair combed high under it, and spurs on her boots, she was a sturdy and pleasing figure. Standing in front of her was a slovenly looking sailor, the band of his cap so loosely fastened that it hung almost over one eye. On it I read the name of his ship, the Pamjat Asowa, In Memory of Asow – Asow, the revolutionist.’

The creation of an all-women’s battalion in the Russian Army was one of the few such examples in history to that time. It would be an example to a future generation of Russian women.

After the failure of the Kerensky Offensive, Lavr Kornilov, the most powerful Russian general still holding a field command, had determined that the only way to save Russia was to remove the Provisional Government by force and restore the Romanov dynasty to its proper place in Russian governance. Conservative newspapers in Russia had turned Kornilov into something of a folk hero and saw him as the best way to prevent a radical revolution from breaking out in Russia. He seemed the last best hope for stopping the rise of the urban-based soviets, which had grown tremendously in influence and power since the summer. Many Russian conservatives had begun to talk openly about Kornilov seizing power for himself rather than trying to resuscitate the Tsar and his incompetent regime. Kornilov proved more than receptive to their ideas and his relationship with Kerensky subsequently deteriorated.

The situation grew much more tense after the fall of Riga. Kerensky and Kornilov each blamed the other for the military failure and, while both recognized the need for change, they shared too much mutual mistrust to work together, even in the face of a common threat to both of them from the revolutionary parties. In an exchange of notes sent through intermediaries (the two were no longer communicating directly with one another), Kerensky and Kornilov discussed Russia’s future (as well as their own projected places within it), but it soon became clear that they had diametrically opposed visions of what a future Russian government might look like. Leftists and moderates began to worry that Kornilov was plotting a coup that would roll back all of the many gains Russia had made since the abdication of Nicholas II.

Born Leon Davidovich Bronstein in the Ukraine in 1879, he was an early opponent of Nicholas II and an advocate of Marxism. Escaping from a Siberian prison in 1902 he took on the name Trotsky and soon became an important adviser to Lenin, especially on military matters. As the Red Army’s Commissar for War he played key roles in ending Russia’s participation in World War I as well as directing Soviet military policy during the Russian Civil War and the Russo-Polish War. In 1924, after Lenin’s death, he lost the succession struggle for control of the Soviet Union to Joseph Stalin, who then exiled him to Turkey. In 1937 he moved to Mexico on the invitation of his friend, artist Diego Rivera. There on 21 August 1940 a Soviet agent assassinated him. George Orwell based Snowball the pig in the book Animal Farm on Trotsky.

On 9 September, Kerensky concluded that the danger of coup had become too great to ignore. He ordered Kornilov removed from command despite veiled promises in the exchange of notes that he would not do so. An enraged Kornilov felt that he had been betrayed and defied the order. Claiming that the revolutionary threat to Petrograd put the nation in grave danger, he sent a detachment of soldiers toward the city on the ostensible grounds of providing the law and order that the provisional government could not. Petrograd workers, most of whom loathed Kornilov for his advocacy of the Tsar and his repeated insistence on being allowed to restore the death penalty for desertion, reacted to the news with alarm and panic. So, of course, did Kerensky, who presumed that the coup he had so feared was about to begin.

The tensions inside Russia were reflected as well in an increasingly tense environment in the cities. The number of strikes was on a dramatic increase, as industrial workers voted with their feet much as deserting Russian soldiers had been doing. Amid food shortages, fears of a German occupation and general uncertainty about the future, the numbers of Russian workers on strike increased from 41,000 in March to 385,000 in July. These numbers, generally corresponding to the period of the Provisional Government, were frightening enough. But the failure of the Kerensky Offensive and the loss of Riga were met with newer and larger waves of strikes. In August, 380,000 Russian workers went on strike, with an amazing rise in September to 965,000 workers on strike. More and more radical leaders began to assume leadership of these strikes, with many calling for industrial sabotage, class warfare and revolution.

Leon Trotsky used his ideological fervour and his passionate speeches to inspire Russian workers to take up arms. He famously declared, ‘You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.’

Among the rising stars of the radical revolutionaries was a member of a long-standing revolutionary family in Russia. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born into a family of schoolteachers and civil servants. In 1887, when he was just 17, his brother was executed for his part in an unsuccessful plot to kill Tsar Alexander III. The young man, who changed his name to Lenin, was expelled from school for his revolutionary talk and later exiled to Siberia. In 1900 he left Russia to study and think about Marxism and how it might be useful to Russia’s future. In 1905 he returned to Russia amid the revolutionary events of the end of the Russo-Japanese War as a dedicated member of the Bolshevik Party, which was committed to a violent overthrow of the Tsarist regime by a dedicated revolutionary vanguard. When the Tsar kept his hold on power, Lenin went back into exile, initially in Finland and then in Western Europe.

‘Russian soldiers who had fought brilliantly under Brusilov and won victories under Kornilov were on the run.’

A journalist describes the Russian Army in August 1917

He spent most of World War I in neutral Switzerland where he had concluded that the war was an imperial struggle of no possible gain or benefit to the working class. Lenin believed that imperialism was the last stage of capitalism and that therefore the time was right for moving to the next stage of the Marxist struggle, the destruction of the capitalist classes. He urged workers in the belligerent nations to stop fighting one another and take up arms in an international class struggle to rid the world of the capitalists who had created the conditions that made the war possible. In February 1917, the German Government saw the value of inserting Lenin and several other revolutionaries into the Russian maelstrom in the hopes that they might further destabilize the Russian political system. The Germans transported the Russians in a sealed train through Germany, Sweden and Finland, and arranged for them to enter Russia.

Lenin’s appearance at first made little real difference to the political situation in Russia. Seen even by many of his supporters as an intellectual who had had little practical experience of the war or the social changes inside Russia, he had trouble assuming the leadership mantle of the Bolsheviks he had so craved. In July, the Bolsheviks had made a clumsy attempt to gain power, but it had failed, and this had temporarily reduced the profile and the power of the party. It had also sent Lenin running to Finland for fear that Kerensky might order his arrest. By the time of the Kornilov crisis, however, he and the Bolsheviks spoke for a large and growing number of Russian workers. They advocated an end to the war, a redistribution of land, and the immediate delivery of food to the starving Russian cities. ‘Bread, peace and land’ was a simple and alluring slogan to Russian workers amid the chaos and anxiety of 1917.

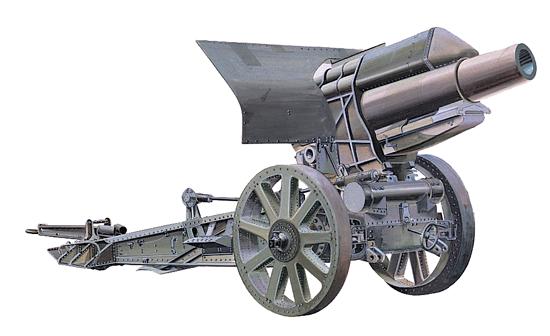

The Russians had few answers in 1917 to Germany’s artillery dominance. This 21cm howitzer was powerful enough to eliminate almost any field defences the Russians created. It could fire a shell 9144m (10,000 yards).

To meet the threat that Kornilov seemed to pose, Petrograd’s highly motivated and disciplined revolutionary workers made a temporary alliance with Kerensky’s Provisional Government. Lenin and the Bolsheviks supported the alliance. At this stage, each of them feared Kornilov’s anticipated coup (and with it, the return of the monarchy and all of the retribution it could be expected to mete out to its enemies) more than they feared one another. With the army in complete disarray and some of it probably still following Kornilov’s orders, the workers provided the only large source of power upon which the government could call. Speaking on behalf of the Bolsheviks, Lenin made it clear that the alliance was temporary and that he was only cooperating because he saw Kerensky as the lesser of two evils.

Russian revolutionaries storm the Winter Palace in Petrograd after it became clear that the palace’s guards would not fire upon them. The incident marked the end of the Provisional Government and the culmination of the October Revolution.

Sailors check papers in Petrograd during the tense days of 1917. The imminent collapse of the Tsar’s government created a whirlwind of tensions and mutual suspicions across Russia, but nowhere as intensely as in Petrograd.

Inside the city, workers were quick to form militias and units for self-defence against any forces Kornilov sent against them. These forces were organized under the authority of the Congress of Soviets, a body dominated by many key Bolshevik leaders. Throughout the crisis, the Bolsheviks proved to be the best organized and most enthusiastic members of the militia, which both heightened their overall prestige and gave them important advantages in the days to come. In large part thanks to their boldness and initiative, the workers of the city were now armed and organized to resist.

Kornilov’s coup, which probably never stood a chance of succeeding, quickly fell apart. Railway workers refused to help transport either Kornilov’s men or their arms toward the city, forcing them to approach the city on foot. The delay gave the soviets more time to organize and the Bolsheviks more time to assume the most important leadership positions. Workers from the Petrograd Soviet marched out to meet the force Kornilov had ordered into the city. They convinced the soldiers that Kornilov’s plot was an attempt at counterrevolution and the soldiers ended their march with virtually no bloodshed on 12 September. Thousands more soldiers deserted, many of them to the Bolsheviks. Kornilov and several other generals were arrested, although Kornilov himself eventually escaped from jail and later died in the Russian Civil War as a general for the ‘White’, or Tsarist side. The threat to Petrograd was over, although to many the crisis had also shown the unwillingness of Russian soldiers to keep fighting.

Revolutionaries take to the streets in a show of force. Many of them were former soldiers, as is indicated in the photograph by the weapons and uniforms of the Imperial Army. The Revolution soon dissolved into the Civil War, which lasted until 1921.

With Kornilov in jail, the Bolsheviks no longer needed Kerensky. The leader of the Provisional Government tried to make some adjustments to their liking by forming a new cabinet with more socialists, but Kerensky no longer had the power to hold Russia together. In late October the Bolshevik Central Committee decided on an armed revolution to eliminate the provisional government and seize power for themselves. By 25 October, Leon Trotsky had done much of the work to set up a leadership organization for the Revolution based around 20,000 members of the Red Guards, all of them members of the party and almost all of them armed. Trotsky also worked to build links to the leaders of 150,000 soldiers and 80,000 sailors willing to support the Revolution.

On 24 October, Trotsky and the Bolshevik leadership put their carefully crafted plan into action. It was timed to take place as the second Congress of Soviets was set to begin its session. Pro-Bolshevik members of the soviets stormed the Winter Palace, the seat of the provisional government, and arrested several government ministers. Kerensky himself fled from the city, never to return. Soldiers, sailors and workers took control of most of the key centres of power inside Petrograd as tens of thousands of loyal Bolsheviks fanned out through the city. Partly because of its audacity and partly because of the careful planning, the seizure of power took place with almost no violence. The second Russian revolution of the year (called the October Revolution) was underway.

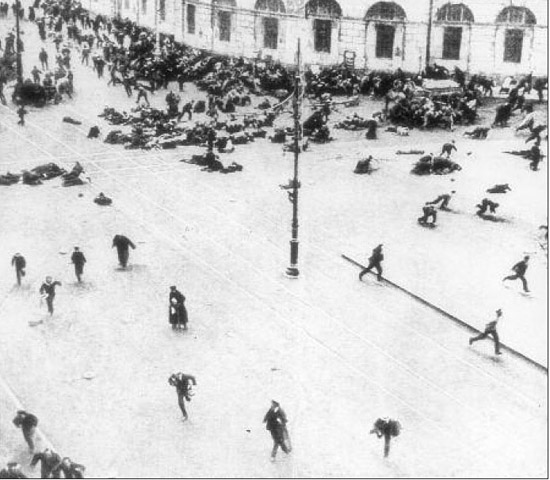

A famous photograph showing the street violence outside the Duma that underscored the tense and unstable environment in Russia after the October Revolution. The Bolsheviks emerged from the chaos as the best organized and best disciplined of the groups.

After his abdication, Nicholas II was sent with his family to the Siberian city of Ekaterinburg. On 18 July 1918 revolutionaries from the Ural Soviet executed him, his wife and all of their children.

The next day the Congress of Soviets met. Over 60 per cent of the members were Bolshevik. Many of the non-Bolshevik members withdrew in disgust at what they saw as an illegal and provocative seizure of power. Still, no group had the power or the boldness to try to remove the Bolsheviks, and most of the senior officers of the army showed little sign of wanting to involve themselves in the crisis. The Bolsheviks proposed a wide and far-reaching programme of reform throughout Russia, but what interested most foreign observers to these incredible events was the position the party planned to take on the war. Although the leaders of the Bolsheviks had denounced the war in their speeches what would they do now that they actually held power? Would they pull Russia out of the war or would they do as Kerensky had done and harness the war to the new Russian revolutionary spirit? Would they try to export their revolution across Europe, especially to Germany or Austria-Hungary where food shortages and accusations of government incompetence had become increasingly common?

After his abdication, the fate of Nicholas hung precariously in the balance. British Prime Minister David Lloyd George offered to give Nicholas refuge in Great Britain, but King George V (Nicholas’s cousin) blocked the offer, most likely because he did not want to be associated with Nicholas’s brand of royal absolutism. After the Bolshevik seizure of power, Nicholas was moved to Siberia where we was executed on 17 July 1918 and placed in an anonymous grave. In 1979, his remains were found, but they were not unearthed until the end of communism in 1991. In 1998 he was given a proper funeral and entombed in St Petersburg. The Russian Orthodox Church canonized him two years later.

Lenin gave the world part of the answer in his first speech to the Congress of Soviets on 8 November. He called for ‘all warring peoples and their governments to open immediate negotiations for a just, democratic peace’. He also proposed an immediate armistice for a minimum of three months. The manifesto was approved unanimously and ending the war became a key Bolshevik policy, although Lenin, Trotsky and other leaders were careful to keep their exact conditions for ending Russia’s part in the war secret. They seem to have held out the belief that they could appeal to German reason to assure a reasonably just end to the war. They were to be sorely disappointed.

Members of the ‘Red Guard of the Proletariat’, as the Worker’s Army was renamed, stand guard at the gates of the Winter Palace. The Red Guard gave the Bolsheviks an armed presence that could be used on the streets or as a veiled threat of violence against their enemies.

Kerensky’s fall from power was swift. After the Bolshevik takeover a warrant was issued for his arrest. He was saved by an American diplomat who smuggled him out of Petrograd in a car flying an American flag. Although he initially wanted to build an army to march back on the city, he was persuaded that the Provisional Government had ended. Still just 36 years old, he accepted an American offer of passage to the United States. He lectured at several universities and for a time became a sought-after public speaker on matters of the war and how to defeat communism. He moved to New York where he died in 1970.

Unlike Kerensky, the Bolshevik leaders had little interest in working with the capitalist western Allies. They soon published the texts of secret treaties and diplomatic understandings that they found in the Winter Palace and the government archives. These agreements showed French and British support for Russian territorial gain, especially at Turkey’s expense with regards to Constantinople. This seemingly revealed what the Bolsheviks had been arguing all along, namely that the war had been fought for imperial interests, not out of self-defence. The publication of these terms embarrassed Allied diplomats who had claimed in public that no such agreements existed. This also angered the American who had advocated a peace without annexations.

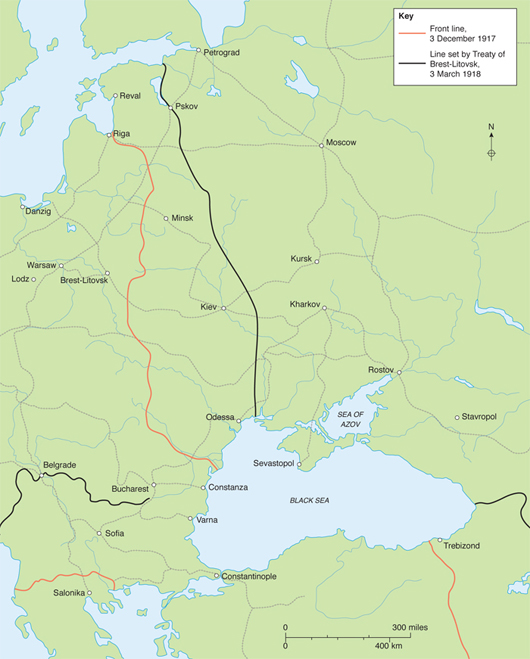

True to their promises, the members of the new Russian Government made overtures to the Germans about an armistice. No longer bound to the western Allies, they had no reason to honour the Provisional Government’s promise not to sign a separate peace treaty with Germany. Facing the real possibility of civil war with several different anti-Bolshevik factions inside Russia, the Bolsheviks hoped to end the war with Germany and move on to the primary task of completing the success of the revolution and ending all possibilities of counter-revolution. Trotsky took charge of the negotiations, hoping to acquire peace without having to surrender much of the territory that Russia had held in 1914. His was an impossible task given German attitudes on the subject of peace in the east, but he managed to obtain an armistice with the Germans that temporarily ended active combat on 5 December 1917. Trotsky then headed to the formerly Russian fortress of Brest-Litovsk (in modern-day Belarus) for negotiations with the Germans on the treaty that would end Russia’s participation in the war.

A German armoured car patrolling the streets of Kiev. The Germans found that defeating the Russian Army was only half the battle. They still had to impose their will on the Ukraine and other parts of Russia they occupied.

If Trotsky thought that the ongoing war in the west would make the Germans more likely to negotiate a compromise peace, he was soon disappointed. The Germans had already concluded that they would exact a winner’s peace on the Russians. They believed that they had acquired the right of conquest over anything and everything their armies had taken. Moreover, they looked aghast at any proposal to give back voluntarily what German soldiers had fought and died to win. They also had decided that they would need to take as many natural resources out of Russia as possible to give their forces the best possible chance of winning the war in the west. Seized grain and fuel from Russia would compensate for losses to the British blockade, even if the seizures reduced whole sections of occupied Russia to starvation conditions, as happened in the Ukraine and Belarus.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was one of the most lopsided agreements in history. It gave the Germans more than 1,600,000 square kilometres (620,000 square miles) of Russian territory, but it also inspired the British and French to fight even harder

There had been voices for moderation inside the German Government, especially that of Foreign Minister Richard von Kühlmann. He had hoped that a quick peace treaty with only small border adjustments would allow the Germans the chance to focus their energies on the war in the west and perhaps find a way to insert some provisions that might help Austria-Hungary avoid disillusion and dismemberment. Although few Germans paid any attention to the desires of Austria-Hungary, the empire’s representative, Ottokar von Czernin, also favoured a lenient peace. The two foreign ministers had issued a joint declaration stating that the Central Powers sought a ‘general peace without forcible annexations and indemnities’.

Hindenburg and Ludendorff, however, showed who really ran Germany by rejecting the diplomats. and their talk of a compromise peace out of hand. They demanded that Russia be dismembered, and that the Germans annex all the territory they could. The two soldiers demanded border adjustments that would make a future round of war with Russia easier to conduct and envisioned removing all Russians from the Baltic states and turning them into ‘settlement areas’ for Germans. Their plan would have deprived the Russians of virtually all access to the sea, turning the Baltic into a ‘German lake’.

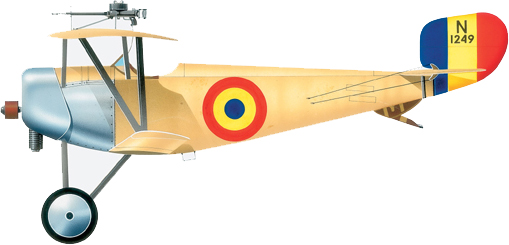

The Nieuport 11 aeroplane was one of the most versatile and popular planes of the war. Built by the French, it also saw service with the British, Belgian, American and Russians.

Ludendorff also spoke of creating permanent barriers between Germans and Slavs in the east. The powerful duo threatened the German Government with a joint resignation if the diplomats altered these demands or failed to attain all that the generals demanded. Much to Kühlmann’s disappointment, several key leaders of Germany’s business community sided with the soldiers and demanded heavy reparations and annexations of key Russian mines and oil wells.

Thus the German plan was clearly staked out. Although Kühlmann sat as the titular head of the German delegation to Brest-Litovsk, the real head of the mission was General Max Hoffmann, the same man who, as a lieutenant-colonel in 1914, had designed the operational plan for Tannenberg. Frustrated at what he saw as German military arrogance and domination, Czernin threatened to sign a separate Austro-Hungarian peace with the Russians. The Kaiser responded by comparing Austro-Hungarian ‘perfidy’ to that of Italy in 1915, and Hoffmann threatened that he would reassign the 25 German divisions protecting the Austro-Hungarians from a renewed Russian offensive to the Western Front if the Austro-Hungarian delegation made any separate overtures to the Russians. The German Army had won the internal struggle to set the terms of the peace treaty. Now it had to deal with the Russians.

For their part, the Bolshevik leaders favoured signing a peace with the Germans, even on disadvantageous terms. Lenin and Trotsky knew that they needed to prepare to fight a civil war and that their regime could not possibly survive a civil and foreign war at the same time. Lenin preferred an immediate peace in order to allow the Bolsheviks to move forward. Trotsky favoured stalling for as long as possible because he believed that a Bolshevik revolution in Germany was imminent. The rising of Europe’s working classes that he expected would give him all of the bargaining power he would need. Still, he must have known how little he had to offer at the peace negotiations, having already publicly stated his support for ending the war on almost any terms.

German soldiers head to Finland, which was formerly a province of Imperial Russia but became an independent state after 6 December 1917. The Germans fought on the ‘White’ side in the Finnish Civil War that followed.

Discussions at Brest-Litovsk began on 17 December. The Germans had already concluded that the Russians had no cards to play at the bargaining table and had proceeded accordingly. They had ignored the clause in the armistice that had forbidden the two sides from moving forces across the front and had instead redeployed their units to make any resumption of hostilities easier to begin. They had also begun separate negotiations with a provisional, generally pro-German, Ukrainian Government, even though the Bolshevik Government still claimed control over the Ukraine.

The Bolshevik delegation arrives by train at the city of Brest-Litovsk for negotiations with the waiting Germans. Leon Trotsky (centre, in the fur hat) headed the Russian negotiating party. Max Hoffmann, one of the victors of Tannenberg, represented Germany.

Early negotiations were tense and acrimonious from the start. Even though their insertion of Lenin into Russia had helped to make the October Revolution a possibility, the Germans looked down their noses at the Russians. They despised having to negotiate at all with Slavs and equally despised the political ideology of Bolshevism. More importantly, Hoffmann saw no need to give in at all to a people he believed had been fully conquered and beaten. Despite the ongoing discussions about peace, German soldiers talked openly of ‘the eventuality of energetic military measures against the Russians’ being resumed in the near future. Hoffmann made it clear to Trotsky that the Russians were at Brest-Litovsk to sign documents prepared by the Germans, not to haggle over terms.

Despite the pressures on him to sign a treaty, Trotsky could not accept German terms and walked out of the negotiations in February 1918. Kaiser Wilhelm responded by announcing a plan for the unilateral division of European Russia. Poland was to be given to the House of Württenberg, Lithuania to the House of Saxony, the rest of the Baltic states to his own House of Hohenzollern and Finland to his son, Oskar. The Austrians got nothing. At a conference at Bad Homburg, Hindenburg promised to resume the war within one week and demanded the outright annexation of the Baltic states to Germany ‘for the manoeuvring of my left wing in the next war’. Ludendorff went even further, proposing a new round of war in the east to eliminate the Bolsheviks and prepare for the addition to the German Empire of Armenia, Georgia and the western coast of the Caspian Sea. The French, British and Americans, presumably, could be dealt with in 1919 or even later.

The conference opened in the presence of representatives of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria. Field Marshal [Paul] von Hindenburg and Field Marshal [Conrad] von Hötzendorf charged Prince Leopold of Bavaria with the negotiations, and he in his turn nominated his chief of staff, General [Max] Hoffmann. Other delegates received similar authority from their highest commander-in-chief. The enemy delegation was exclusively military.

Our delegates opened the conference with a declaration of our peace aims, in view of which an armistice was proposed. The enemy delegates replied that that was a question to be solved by politicians. They said they were soldiers, having powers only to negotiate conditions of an armistice, and could add nothing to the declaration of Foreign Ministers [Ottokar] von Czernin and [Max] von Kühlmann.

Our delegates, taking due note of this evasive declaration, proposed that they should immediately address all the countries involved in the war, including Germany and her allies, and all States not represented at the conference, with a proposal to take part in drawing up an armistice on all fronts.

The enemy delegates again replied evasively that they did not possess such powers. Our delegation then proposed that they ask their government for such authority. This proposal was accepted, but no reply had been communicated to the Russian delegation up to 2 o’clock, December 5th.

Our representatives submitted a project for an armistice on all fronts, elaborated by our military experts. The principal points of this project were: First, an interdiction against sending forces on our fronts to the fronts of our allies, and, second, the retirement of German detachments from the islands around Moon Sound [near Riga].

The enemy delegation submitted a project for an armistice on the front from the Baltic to the Black Sea. This proposal is now being examined by our military experts. Negotiations will be continued tomorrow morning.

The enemy delegation declared that our conditions for an armistice were unacceptable and expressed the opinion that such demands could be addressed only to a conquered country.

The conference at Bad Homburg showed how badly divorced from reality the German high command really was. The diplomats thought about a mass resignation in protest, but there was no real point in an empty gesture. Instead, they completed the treaty with the Ukraine, promising not to annex it in return for more than six months’ worth of grain and minerals. The Germans and Austro-Hungarians also released all Ukrainian prisoners of war. As a result, the Russians invaded the Ukraine, plunging that country into a bloody civil war and forcing the Germans to leave more than 650,000 men in place to maintain order after the assassination of the German commander Field Marshal Hermann von Eichhorn by a Ukrainian nationalist. As a result of all the chaos, the Germans never realized even a fraction of the grain that they had hoped to get from the Ukraine.

In mid-February the Germans resumed the offensive against Russia with more than 50 divisions. Turkish units also renewed their attacks in the Caucasus Mountains. German troops advanced with ease against only light opposition from Russian troops who had been told to expect peace. The Germans gained hundreds of kilometres, taking key cities like Dvinsk and Kiev and preparing to move into Bessarabia and the Crimea. Helsinki, still under nominal Russian control, fell as well, along with 25,000 Russian defenders who surrendered en masse.

The German offensive, and the lack of an effective Russian response to it, finally proved to Trotsky and Lenin that they had little choice but to sign whatever the Germans offered. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on 3 March 1918, and gave the Germans terms that led the Kaiser to dub it one of the great successes in world history. The territorial concessions forced Russia to cede control over more than two-and-a-half million square kilometres of territory. Russia recognized the independence of the Ukraine (in effect a German satellite) and Finland as well the transfer of the Baltic states to German crown princes. Poland was also removed from Russia, with its final status to be determined after a conference between the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians. German gains ranged as far east as the Crimean Peninsula and the west bank of the Don River. The land Russia gave up held 62 million people.

The famous Luger P08 Parabellum pistol. Although more commonly associated with World War II it had been issued to German officers since 1904. It could be converted into a machine pistol that fired 9mm ammunition.

Russian and German delegates sign the final Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Both Trotsky and Lenin saw the lopsided treaty as a necessary evil needed to buy the revolution time to strengthen itself against internal enemies.

The economic concessions of Brest-Litovsk were just as staggering. In the lands Russia ceded sat almost 90 per cent of its coal and half of its heavy industry. Russia also gave up tonnes of grain and oil, which the Central Powers divided among themselves. Austria- Hungary took the lion’s share, not out of German kindness, but because the lines of transportation were easiest to manage. The Germans also took mountains of rifles, artillery pieces, and ammunition for use in their grand offensive in the west, expected to begin soon. By October 1918. the Germans had taken away 47,174 tonnes (52,000 tons) of grain, 30,844 tonnes (34,000) tons of beet sugar, 45 million eggs, 53,000 horses and 48,000 hogs. Still, to enforce the treaty and ensure themselves of the ability to take such vast amounts from starving peasants, the Germans had to dedicate almost one million men to the Eastern Front for the duration of the war.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk ended the war for these Russian prisoners of war. Unfortunately for them, most would not see peace for four more years as Russia descended into a civil war that killed millions.

Despite the need to keep so many men in the east, for the Germans, Brest-Litovsk finally meant that they could focus on one front exclusively. The Germans hoped to move 45 divisions from the east to the west to reinforce the Spring Offensives and crush the French and British before the Americans began to arrive. A more lenient and reasonable treaty might have permitted them to transfer even more men to the west, but such was not the thinking at German high headquarters. The Germans hoped that Brest-Litovsk would provide enough resources to feed the home front and thereby bolster its morale for the final push in the west. They also hoped that the treaty might provide some badly needed succour to faltering allies as well. All in all, they thought that they had done quite well for themselves.

By order of the All-Russian Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Congress, the Council of The People’s Commissaries assumed power, with obligation to offer all the peoples and their respective governments an immediate armistice on all fronts, with the purpose of opening discussions immediately for the conclusion of a democratic peace.

When the power of the council is firmly established throughout the country, the council will, without delay, make a formal offer of an armistice to all the belligerents, enemy and ally. A draft message to this effect has been sent to all the Peoples’ Commissaries for foreign affairs and to all the plenipotentiaries and representatives of allied nations in Petrograd.

The council also has sent orders to the citizen commander-in-chief that, after receiving the present message, he shall approach the commanding authorities of the enemy armies with an offer of a cessation of all hostile activities for the purpose of opening peace discussions, and that he shall, first, keep the council constantly informed by direct wire of discussions with the enemy armies, and, second, that he shall sign the preliminary act only after approval by the Commissaries Council.

For the Russians, the treaty was a great humiliation. Lenin nevertheless urged that it be signed out of fear that the Germans might resume the offensive if the Russians refused. He had also seen how much more vindictive the Germans had grown as a result of Trotsky’s first refusal to sign in February. He remained confident that the treaty’s harsh terms would be temporary and that a working-class revolution would soon break out in Germany and reverse all of the concessions. He was also aware of how weak his domestic powerbase was and knew he had to For France, Britain and the United States, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk provided additional motivation to win the war in the west. Alongside the equally harsh treaty the Germans had signed with Romania, the western Allies had seen what the question, no matter what the price of victory turned out to be. Germany’s realization of some of its greatest desires, namely the humiliation of Russia and the chance to fight on only one front, ironically helped to sow the seeds of its final demise. The Germans, who failed to understand their countryman Carl von Clausewitz’ s famous dictum that war is the extension of policy by other means, had fought war for war’s sake. It was to be their final undoing.

‘Their knees are on our chest, and our position is hopeless. peace must be accepted as a respite enabling us to prepare a decisive resistance to the bourgeoisie and imperialists.’

Lenin urges acceptance of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, 23 February 1918