British troops were initially deployed to Murmansk to protect supplies that had been shipped there for the use of the Russian Army on the Easton Front. From left to right, General Edmund Ironside, General Evgenii Miller, Colonel Thornhill, General Savitch and Count Hamilton.

Following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk the Allied powers looked on in alarm as the war on the Eastern Front ground to a halt. In order to rescue something from the collapse of Tsarist Russia the Allied powers decided to intervene militarily. At first this intervention was limited to North Russia, but it gradually spread in both its aims and locations, reaching South Russia and Siberia and involving tens of thousands of men.

The decision by the Bolsheviks to pursue a peace settlement with the Germans was a matter of great concern to the Allies, since the punitive nature of Brest-Litovsk offered the prospect of the Germans gaining pre-eminence in Eastern Europe. Some observers felt that the Bolsheviks’ renunciation of the Pact of London in seeking a separate peace justified intervention against the new Russian Government, but this was not a view shared by Allied governments. Although the Bolsheviks’ fundamental political position was diametrically opposed to that of all the Allied governments, there were sound practical reasons for seeking to engage the new Russian regime rather than oppose it. The first rationale behind attempting to formulate some measure of cooperation with the Bolsheviks was simple – they might, perhaps, be persuaded to challenge the terms of Brest-Litovsk and reactivate the Eastern Front, a course that would have been a grave threat to the Germans. Second, the Allied nations had established many commercial links with Tsarist Russia, and there were good economic grounds for not taking action that might prompt retaliation against those interests. In addition, there were large numbers of Allied citizens in Russia who might be at risk if the Allies openly opposed the Bolsheviks.

With armies committed to the war in Europe and a bitter power struggle between the factions at home, Russia’s need for manpower was voracious. Some of those who ‘voted for peace with their feet’ and deserted the war in Europe ended up fighting their own countrymen instead.

The Allies were aware that opposition to the new regime had begun to coalesce almost immediately after the October Revolution, creating the movement that would ultimately become known as the ‘Whites’. The sheer size of Russia, coupled with the turbulent political situation, meant that the Bolsheviks were far from being in complete control of the country. The prospect of the Bolsheviks losing their hold on power was a possibility, and it seemed sensible to some politicians in Allied nations that it would be best to adopt a position of attempting not to alienate the Bolsheviks, in the hope of maintaining their support in the war with Germany, while simultaneously giving aid to the opposition movement as part of an ‘anti-Bolshevik crusade’. Other considerations were to influence the Japanese decision to intervene in Siberia, further complicating understanding of the way in which the intervention proceeded. A further complicating factor was that of the Czech Legion. This was a large force of troops drawn from Czech and Slovak nationals that found itself trapped in Russia after the Revolution and desperate to depart to continue the war effort. One aspect of the intervention by the French and British was to enable the Czech Legion to leave so that it could be redeployed to the Western Front.

Finally, the Allies were sympathetic to the claims of nationalists in the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and particularly towards the Poles, who were to be granted their own state in the post-war settlement, but who would have to overcome the fact that much of the territory that they thought should be included in their new homeland was under Russian control. In many ways, then, securing the self-determination of new states was the firmest justification for Allied intervention in Russia.

The deployment of Allied troops in post-revolutionary Russia thus occurred in an atmosphere of confusion and chaos as the battle for control of the country took place between the Bolsheviks and their enemies, and as the Germans sought to exploit the Bolshevik commitment to withdraw from a war that had exhausted the Russian people.

Such was the confused and uncertain political situation in Russia that the Bolsheviks asked the Western Allies for help while negotiating peace with Germany. A token British presence in Murmansk gradually grew into a major force formed of British, French and local troops.

Earlier in the war a British naval presence had been established in northern Russia to provide an antisubmarine capability in northern waters. The task force operated out of Archangel in the summer months, and from the ice-free port at Murmansk from November to May. Large amounts of supplies were sent to Murmansk, both to sustain the Royal Naval units based there and for onward transmission to the poorly equipped Russian forces, who needed all the war matériel that they were sent. A single-track railway was built from Murmansk to Petrograd to take the supplies onward. After the October Revolution, the British became increasingly concerned about the safety of their supplies, a fear that was realized in late January 1918 when a Bolshevik ‘Extraordinary Commission’ arrived in the port and began to commandeer the supplies stockpiled in Murmansk for use by their own forces. This was not the only problem confronting the British, since a number of Russian ships were harboured in the port and their crews were particularly enthusiastic supporters of the Bolshevik Government. This meant that the Russian ships presented a potential threat to the safety of the Royal Navy vessels. To complete the list of issues that were of profound concern to the British, the Germans had sent troops to Finland to support the White Finns, fighting a civil war against the communists (the Red Finns) who had seized power there. The degree of German support was over estimated, but it was a cause of considerable worry to the Murmansk Soviet, who were deeply fearful of the possibility of a German attempt to occupy the port. As a result, and indicative of the confused and sometimes almost farcical situation in post-revolutionary Russia, the Soviet hit upon the idea of making use of the British presence to sustain their own position. They sent a telegram to Leon Trotsky, asking whether they could seek help from the British. At this point, Trotsky was fearful that the peace negotiations with the Germans would end in failure, and that the war would resume. He had few illusions about the ability of the Bolsheviks to survive a sustained assault by the Germans, and therefore accepted the notion of a British intervention in Murmansk with equanimity. He told the Soviet that they should accept help from any of the Allied missions, and not just the British. However, the British were the first to be asked, and they dispatched a small force of Royal Marines, who landed in Murmansk on 6 March 1918.

The aircraft carrier HMS Vindictive, converted from a Hawkins-class heavy cruiser, was dispatched to the Baltic in June 1919 to provide support for Admiral Cowan’s assault on the Bolshevik naval base at Kronstadt.

While the company of marines was little more than a gesture to the Murmansk Soviet, it represented a foothold that could be exploited to deny the north Russian coast to the Germans; it also proved to be a precursor to a much larger commitment of British troops to the region. In May 1918, at the Abbeville Conference, the Allies reached the conclusion that intervention in Russia was a good idea, since it would permit the extraction of the Czech Legion and Serbian troops then stationed west of Omsk from Russia. The story of the Czech Legion will be outlined below, and as will be seen, they did not leave via Murmansk as the Allied plan intended. By this point, however, the British intervention had expanded to a point that was rather more ambitious than perhaps originally conceived.

The prospect of a Bolshevik naval attack on the Royal Navy’s small force in the Baltic caused considerable concern to Admiral Cowan, and he signalled the Admiralty to point out that the units at Biorko were at considerable risk. The Admiralty was reluctant to allow Cowan to attack the Bolshevik base at Kronstadt to remove the threat, and he was forced to consider other options.

The answer lay in the detachment of coastal motor boats (CMBs) that had been sent to Terrioki, near the Finnish border, and which were being used for intelligence operations, particularly agent running. Cowan sent the detachment commander, Lieutenant Augustus Agar, a consignment of torpedoes, with the intention that these should be used should an opportunity to attack Bolshevik shipping present itself.

On 13 June 1919, an opportunity presented itself when the garrison of Krasnaya Gorka mutinied. Admiral A.P. Zelenoy, the commander of the Bolshevik Baltic Fleet, gave order for two battleships to bombard the fort; once this was known, Agar set out to attack the two vessels, using two CMBs. Unfortunately for Agar, one of the CMBs struck an underwater obstacle and the operation had to be aborted. Agar was dismayed to learn that the two battleships had departed overnight, but spirits amongst the CMB detachment rose when it became clear that they had been replaced on station by the cruiser Oleg. Although Agar only had a single CMB at his disposal, he decided that he would attack that night. At 11pm on 16 June, CMB4, commanded by Agar and with Lieutenant J. Hampshier and Chief Motor Mechanic M. Beeley as his crew, left Terrioki and headed towards the Oleg‘s last known position. They negotiated their way through a minefield with little difficulty. Once this was accomplished, Agar began to manoeuvre CMB4 into a firing position for its torpedo.

The CMBs carried a single torpedo, and this was launched in a rather unorthodox manner. The weapon was ejected rearwards from the stern by a cartridge-fired ram. One of the crew was required to place a cordite cartridge into the ram and then remove two stays that held the torpedo in place. The cartridge was then fired and the torpedo propelled into the water, where its motor would start running, taking it towards the target.

This complicated matters for the CMB, which had to take instantaneous evasive action to avoid being struck by its own weapon. As Agar moved into position, Hampshier prepared the cartridge to launch the torpedo. As he did so, something went wrong and the cartridge fired. As the stays holding the torpedo had not been removed, it remained in place on the boat. Hampshier, already suffering from seasickness, was in mild shock, and Beeley – renowned amongst his colleagues for his imperturbable nature – took over, priming a new cartridge and making the torpedo ready. This took some time, leaving CMB4 and its crew vulnerable to detection as Beeley quietly went about his business, the small craft remaining unseen by the enemy.

There were no mishaps with the second cartridge, and Agar resumed tracking the Oleg, then picked up speed as he took the motorboat through the Russian destroyer screen. Aiming at the hull beneath the middle funnel of the Oleg, Agar released the torpedo and swerved out of the way to give it a clear run to the target. The torpedo struck home, and the Oleg shook under the explosion.

A massive hole had been torn in her side and within ten minutes the ship had gone under. Agar was unaware of this, since he was taking violent evasive action in the face of heavy fire from the destroyers and guns ashore. CMB4 left the scene at high speed and reached the safety of Finnish waters early on the morning of 17 June 1919.

For his actions, Agar was awarded the Victoria Cross, while Beeley received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal and Hampshier the Distinguished Service Cross.

Conditions in northern Russia were rather different from those the personnel assigned there were used to. As well as a political climate that changed almost from day to day, the rather primitive transport system made movement of troops, supplies and senior officers a considerable challenge.

The British commander in Murmansk, Admiral Kemp, signalled London expressing the view that if Murmansk and Archangel were to be denied to the Germans, a force of least 6000 strong would be required, since the company of marines was quite insufficient for the task. No troops were immediately available to meet this request, not least since there was a distinct risk of a major German offensive on the Western Front. Instead, the British and French sent a cruiser each, later to be joined by an American ship, the USS Olympia. Matters were further complicated when Trotsky issued instructions to the Murmansk Soviet that they were no longer to cooperate with the British; having negotiated a settlement with the Germans, Trotsky realized that any signs of cooperation with the Allies would be taken by the Germans as a breach of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, with the probable consequence that the Germans would resume fighting. The Murmansk Soviet was horrified at the thought of having to face what they perceived as an ongoing threat from the Germans alone, and disobeyed their instructions.

As the German Spring Offensives began to lose momentum, the British therefore decided to send more troops, influenced by a report from General Poole, the head of a British military mission to Russia in 1917 that aimed to extract British forces and citizens with the minimum of fuss in the confused situation. Poole had reached the conclusion that the only way of securing an orderly withdrawal from Russia was to ensure that there were sufficient troops in place to make sure that any hostile forces could not interfere with the evacuation. Poole was also well aware of the prospect that abandoning Murmansk and Archangel risked ceding the northern waters to the Germans, and this may have influenced his perspective. In the aftermath of Abbeville, the British sent Poole back to Murmansk as the head of an expeditionary force. The purpose of Poole’s mission was fourfold. First, all British war matériel and personnel were to be withdrawn from Murmansk; second, any effort by the Germans to exploit Russian resources for their own war effort were to be resisted, while, third, Poole was to ensure that the Czech Legion was safely removed from Russia. Finally, Poole was to make sure that the Germans did not advance upon the northern ports. This was a fairly wide-ranging brief, but Poole did not allow himself to be constrained by it. He appears to have decided that the intervention should have a supplementary aim of assisting resistance against the Bolsheviks. Poole went so far as to tell some of his officers that he intended to link up with the Czech Legion and thus reopen the Eastern Front against the Germans. On 23 June 1918, 1100 more British troops under the command of Major-General Maynard arrived, with the intention that part of the force would move to Archangel and train anti-Bolshevik forces and any Czech units that managed to reach the British positions.

It was not obvious to Poole and Maynard how the Bolsheviks would respond to the increased number of British troops in the region, and they therefore took steps to take control of the railway to the south of Murmansk, a task they accomplished by mid-July when British troops reached the point at which the railway branched off towards Archangel.

By August, Poole felt it necessary to deal with the Soviet authorities in Archangel, since they were sending a large number of supplies on to Bolshevik forces elsewhere in Russia. The arrival of a battalion of French colonial troops on 26 July gave Poole the confidence that he had sufficient numbers to attack Archangel. He therefore began the assault on 1 August 1918. Naval gunfire support and bombing by aircraft from the seaplane carrier Nairene destroyed the Bolshevik artillery positions at Modyugski, and this silenced the opposition. Poole’s forces moved into Archangel to discover that the majority of the Bolsheviks had fled. Poole interned the remaining Bolshevik leaders – despite loud protests from the British ambassador – and it was quite clear that the intervention had changed from the parameters initially set for the British forces. The British forces around Murmansk and Archangel would ultimately reach something in the region of 50,000 men, many of them local troops who wished to fight the Bolsheviks. Furthermore, local anti-Bolshevik elements had coordinated with the British to launch a coup in conjunction with the attack. A local government under the veteran socialist leader Nicholas Tchaikovsky was established, but while Tchaikovsky was more than amenable to working with the British – not least because he spoke English fluently thanks to spending over a decade living in Britain – his administration was less than effective. Nevertheless, the Allied forces pushed further south out of Murmansk and at the end of August held positions up to 190km (120 miles) south of Archangel.

The British and French sent thousands more troops to Murmansk and it became possible to act against Bolshevik leaders who had been appropriating Allied supplies. This was a different situation than that envisaged when the intervention was first requested by the Bolshevik leadership.

The British had been joined at this point by an American force that President Woodrow Wilson had finally agreed to send, despite his having severe reservations about the wisdom of any form of intervention in Russia. He imposed strict conditions on the way in which the American troops were to be employed, instructing that they were to be used only for the purpose of guarding stores. He did, however, accept the idea that the troops should be placed under British command, a decision that he was to regret. By the time the Americans arrived in Archangel, the influenza pandemic that had broken out across the world had struck their transport ships; over 300 of the American troops – just under 10 per cent of the force – had succumbed to illness, and 70 of them had died. They arrived to discover that General Poole had decided that they should not be used simply for guarding stores as Wilson had insisted, but would be employed to hold positions on the Murmansk railway and in a projected attack on the Bolshevik positions at Bereznik.

General Edmund Ironside was an active officer with a good grasp of politics,who did much to improve relations between the various nationalities involved in northern Russia. He later served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff at the beginning of World War II.

While the forces in place may have looked impressive on paper in comparison with the then rather disorganized Bolsheviks facing them, the reality was rather different. The British troops were made up of large numbers of men who had been categorized as unfit for front-line operations, but who were now being expected to fight in far more arduous conditions than those on the Western Front. The French colonial troops were utterly perplexed at their lot, being thousands of kilometres away from home and enduring conditions for which they were utterly unprepared – as a result, their morale and fighting effectiveness were low. The American troops were recovering from the depredations of an influenza outbreak, which meant that it would be some time before they were effective. The only saving grace was that the Bolshevik forces confronting this less than healthy coalition of Allied troops were not of the highest standard.

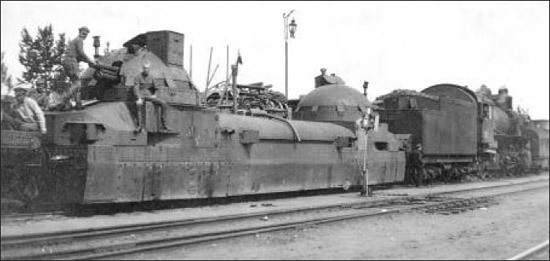

The rail network was of critical importance as it provided the only means of moving large amounts of matériel or troops across very inhospitable countryside. Control of the railways was thus an important objective once the intervention moved beyond merely protecting stores in port.

To make matters worse, the American officers were less than impressed with the fact that President Wilson had agreed to place them under British command, and even less pleased to discover that Poole had no intention of taking them into his confidence or regarding them as being equal partners in the coalition in any way. The British, on the other hand, were intensely annoyed with the assertion by the Americans that they had in some way arrived to rescue the Allied mission from its inadequacies. British officers were concerned at the low quality of the American troops who had been sent, and many British other ranks were decidedly unflattering in their assessment of their newly arrived allies. This may have been influenced by the fact that a remarkably high number of the American soldiers were relatively recent immigrants to the United States who had volunteered to serve their new country long before they had mastered the English language. These frictions meant that it was extremely difficult to fashion the 8500 or so troops at Archangel into an effective fighting force. To complete this unhappy picture, Poole’s constant dabbling in matters of civil government – while understandable given the nature of the local administration in Archangel – meant that he was not paying full attention to building his forces and did nothing to win the support of the Russians.

Once supplies were unloaded from rail transport, sledges such as these were the only viable way to get them to their final destination. This severely limited the mobility of forces, such as these French colonial troops from Africa, away from the towns and railheads.

Although Poole now had over 20,000 men under his command, he wanted more. He requested that the British Government dispatch further reinforcements so that he could attack along the railway and the Dvina, with the aim of encouraging local men to join in the war against the Bolsheviks and continuing the push so as to join up with the Czech Legion, which was still at that point meant to be travelling to Archangel to join the Allied troops. Poole was invited to London to discuss the matter of reinforcements, little realizing that he would not return to Archangel. Doubts within the War Office about Poole’s command style had been confirmed when President Wilson had complained strongly to Prime Minister Lloyd George about a variety of issues, not least the high-handed manner with which he had dealt with the American contingent. Poole was replaced by Major-General Edmund Ironside, who arrived at Archangel in the expectation that he would become Poole’s chief of staff. Ironside was a physically imposing man and possessed of considerable intelligence. He spoke several languages very well – including Russian and French, something of considerable utility in the circumstances in which he found himself – and could manage to make himself understood clearly in several others. In addition, Ironside was a man of great tact and political skill, in direct contrast to his predecessor.

‘The evacuation undoubtedly raised the enemy’s morale, and for a time his continued attacks against our Vaga front were the cause of great anxiety.’

General Sir Edmund Ironside’s official dispatch, the London Gazette, 6 April 1920

Ironside swiftly improved relations between the British contingent and the Americans, and the local Russian leaders were most impressed with him, some said because of his ability (and willingness) to swear at them in their own language. He also took the trouble to visit his geographically separated commands on a regular basis, travelling between Murmansk, Archangel and all points between via sleigh.

Assessing the situation before him, Ironside reached the conclusion that the forthcoming winter would represent a formidable challenge to operations. This demanded a programme of instruction to all troops to explain to them the hazards of the fierce conditions that they were about to face, and serious consideration as to how to sustain the Allied positions dotted around the countryside at Murmansk and Archangel. Over 900 sleighs were procured to transport food, equipment and ammunition amongst the Allied lines. It was as well that Ironside ensured that a robust supply chain was established, since on 11 November 1918, the first major contact between Bolshevik and Allied troops occurred.

The Bolsheviks launched their attack along the Dvina, encouraged to do so by the fact that British gunboats that had patrolled the river until November had withdrawn so as to avoid being frozen in position when the winter came. The withdrawal proved to be premature, since the Bolsheviks were able to continue operating their own gunboats, a fact they exploited by using them to bring down heavy fire on British positions. Despite the various inadequacies of the British and American troops noted earlier, the Bolshevik attack bogged down in the face of stiff, if occasionally desperate, resistance.

While the fact that the Bolshevik attack of 11 November 1918 was defeated was highly encouraging for the Allies, it in fact marked the point at which the nature of the Allied mission to Russia changed fundamentally. The attack occurred on the same day that World War I ended. There was now no need for the Allied mission to remain in Russia for the purposes of reopening a second front against Germany, nor to guard against a German seizure of war matériel. If the Allies were to stay, it would be to oppose the Bolshevik regime – giving the mission an entirely different purpose to that originally outlined. In addition, the fact that the war was over was likely to provoke questions amongst the soldiers, who would naturally wish to return home to their families now that the war was over. Whether volunteers or conscripts, they held firm expectations about their military service coming to an end shortly after the war, and it was questionable as to whether they would be content with being forced to continue to serve after the cessation of the war with Germany. This uncertain picture was further complicated in January 1919, with a second major attack by the Bolsheviks. An attack on Shenkursk began in the morning of 19 January, when American positions in the town came under heavy artillery fire. An assault by around 1000 Bolshevik troops followed the bombardment, and came close to dislodging the Americans, who fought a bitter rearguard action to remain in the town. The Bolsheviks responded to their failure to seize the town by putting in another intensive bombardment over the course of the next 48 hours. They accompanied this by sending small units to work their way around the Allied positions, both at Shenkursk and further along the line at Ust Padenga. It became clear that the position was untenable, and the Allied troops in the area conducted a skilful withdrawal at night back towards more defensible positions.

From the end of June 1919, Admiral Cowan’s force in the Baltic was sent reinforcements, initially in the form of four cruisers. These were later joined by minesweepers and the aircraft carrier HMS Vindictive, along with more coastal motor boats (CMBs).

Augustus Agar’s successful attack on the Oleg and the threat presented to his forces led Cowan to the conclusion that not only was an attack to cripple the Red Baltic Sea Fleet necessary, but that it could be conducted using the increased CMB force in conjunction with the newly arrived aircraft. While Cowan planned a combined air and sea attack, the RAF aircraft carried out a number of bombing raids on Kronstadt, although the most successful outcome of the attacks was unintentional: a bomb that had been aimed at a ship instead fell amongst a recently convened meeting of a soviet of sailors and killed over 100 of them.

By 17 August, Cowan had created a plan of attack against Kronstadt, and this began with a bombing raid as a diversion. While the defences were concentrating upon the air attack, they failed to notice the approach of seven CMBs led by Commander Claude Dobson. Dobson’s small flotilla was guided into place by Agar, who knew the waters around Kronstadt well from his agent-running trips, and once in position, launched the attack. The CMBs moved in at low speed to avoid detection, but once in the harbour, they opened their throttles and attacked. The cruiser Pamyat Azova was sunk by Lieutenant W.H. Bremner, while Dobson, who was leading the operation from Lieutenant R. Macbean’s boat, had the satisfaction of participating in a torpedo run that sank the battleship Petropavlovsk. Finally, CMB88, commanded by Lieutenant Dayrell-Reed, attacked another battleship, the Andrei Pervozvanni. As the CMB ran into the target, Dayrell-Reed was mortally wounded, and his number two, Lieutenant Gordon Steele, had to take over; he managed to do so just in time to launch his torpedo into the Pervozvanni, which promptly sank, and then skilfully manoeuvred his vessel, under heavy fire, to launch its second torpedo to deliver the coup de grâce to the Petropavlovsk. Three CMBs were destroyed: Bremner’s boat sank after colliding with CMB62; CMB62, with Bremner’s crew aboard, was lost after being hit by return fire; while CMB24 was blown to pieces by the destroyer Gavrill. The remaining CMBs escaped. The remnants of the Bolshevik fleet now posed only a minor threat to the British forces operating in the Baltic. The success of the raid was such that all the participants were decorated: Dobson and Steele received the Victoria Cross, while Agar, along with three others, received a Distinguished Service Order to add to the Victoria Cross he had won two months before.

The loss of Shenkursk was a serious blow to the Allies, since the success of the Bolsheviks in taking the town and the surrounding area meant that it was now even more difficult to persuade local Russians that the anti-Bolshevik forces being built up by the Allies at Archangel and Murmansk had any chance of success. This had a deleterious effect on recruitment to the anti-Bolshevik army that was in the process of being established, and made locals wary of providing any support to the Allies for fear of retribution by the Bolsheviks.

The standard sidearm for officers and other troops that required one was the revolver. Often chambered for large, hard-hitting rounds, the revolver was more a status symbol than a practical battlefield weapon. The Webley Mk VI pictured was a standard issue sidearm for British officers.

Some Bolshevik units were formed around a core of combat veterans and could be highly effective, while others were little more than a politically-motivated rabble. Many units had a rag-tag appearance but there was no shortage of weapons considering the numbers produced during the war.

This setback prompted Ironside to request reinforcements, which he received in the form of two battalions of British troops. Ironside had also been concerned about the quality of leadership displayed by the White Russian officers, and his observations led to the Whites deciding that General Durov should be replaced by General Marousheffski. Although Marousheffski was a much better general than his predecessor, the fundamental problem that had afflicted the Tsarist army remained – the officers had nothing in common with their men, and did nothing to engage with them; thus the motivation of their troops was low and building them into an effective and determined fighting force was a near impossibility. To make matters worse from Ironside’s point of view, one of the battalions of British reinforcements he had asked for, from the Yorkshire Regiment, mutinied upon its arrival at Onega. The mutiny was swiftly suppressed, and the remaining troops subsequently performed well in combat. The combination of mutiny and poor leadership on the part of the White Russians meant that Ironside faced a major challenge in attempting to gain any sort of success with the intervention. The Allies faced similar problems with all their interventions in Russia, be it in the south or in Siberia.

The Czech Legion started out as a company-sized force formed of ethnic Czechs and Slovaks living in Russia, and grew into a large and professional force that played a major part in events during the Revolution.

Historians often forget the Japanese participation in World War I. Japanese forces did not make a major contribution in the main theatre of the war, namely the Western Front (they suffered a grand total of three casualties, all liaison officers, in France) and it is thus easy to overlook the fact that they were part of the Allied coalition. The Japanese rationale for involvement was simple, in that they sought to increase their influence in the Far East, not least in China. Japan declared war upon Germany in 1914, ostensibly because of the perceived threat presented in the Pacific by the ambitious Germans as they sought more colonies, but the possibility of being placed at a disadvantage if Russia were to be on the winning side while Japan remained on the sidelines, and the prospect of territorial gains as part of the spoils of victory probably played a far greater part in the Japanese decision to intervene. The Japanese Government almost certainly feared the prospect of the Russians gaining some form of revenge for their defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 via the inevitable post-war settlement unless there was a Japanese presence on the side of the victors at the conference table.

The power vacuum that emerged in Siberia in the aftermath of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk gave Tokyo considerable temptation to intervene, not least since there was a fear that the Bolsheviks would be as hostile towards Japan as the Russians had been in the past. Taking control of Vladivostok would remove a major naval base from Russian control and thus reduce the threat. The Japanese therefore concluded that it was desirable to send troops, but faced considerable opposition from the Americans, who suspected that Japan’s motives were not in support of the wider Allied cause, but purely nationalistic. This was a source of annoyance to the British and French, who saw merit in bringing the Japanese into the complicated and uncertain Russian situation. The British, in particular, were concerned that the large stocks of war matériel located at Vladivostok and along the Trans-Siberian railway line would somehow fall into the hands of the Germans and they therefore argued that it was necessary to ensure that these supplies were protected.

Armoured trains allowed heavy and well-protected firepower to be brought to bear. Against an enemy free to manoeuvre as he pleased they were of limited use, but since they moved on the very rail lines that were the target of many attacks, they were at times highly effective.

Japan’s clear regional ambitions were a source of considerable concern to Washington, which enjoyed substantial amounts of lucrative trade with China. The possibility that the Japanese might exploit their involvement in Vladivostok to enhance their position at the expense of the United States was something that President Wilson was quite unwilling to contemplate.

The Japanese, though, were unconcerned by the view from Washington and on 5 April 1918 a Japanese expeditionary force landed at Vladivostok, nominally to ensure that the port continued operating. President Wilson expressed his displeasure at this move, but more seriously, the intervention at Vladivostok prompted Trotsky to give instructions that the trains carrying the Czech Legion to the port were to be stopped in retaliation for the violation of Russian territory. Under intense pressure from their Allies, the Japanese withdrew. Ironically, while the fate of the Czech Legion aborted the initial Japanese involvement in Russia, it was soon to prove the justification for a much larger Japanese presence in the country.

The Czech Legion, more properly the Czech and Slovak Legion, had its origins in the early days of World War I. Czech and Slovak nationalist leaders, anxious to seize any opportunity that might permit the establishment of a Czech and Slovak state independent of Austria-Hungary, petitioned Tsar Nicholas II for permission to establish a corps of Czech and Slovak troops under Russian command. Nicholas was only too happy to oblige, and the corps was established from volunteers living in Russian territory, as well as men who made their way over to Russian lines. The strength of the Czech Corps was boosted as the war went on, as all Czechs and Slovaks fighting as part of the Austro-Hungarian forces and taken prisoner of war were given the option of going to a prison camp or changing sides and continuing to fight. Many of the Czech and Slovak prisoners had been reluctant conscripts to the Austro-Hungarian cause, and willingly joined the Corps. The Corps fought alongside the Russians, and by the time of the October Revolution, they were in the Ukraine. The Supreme Allied War Council, the body coordinating the war for the Allies, exploited the fact that the Czechs were now (at least nominally) under French command, and could thus be given direction without the need for consultation with Petrograd. The Council sought to exploit the Czechs’ presence in Ukraine to reopen the Eastern Front, albeit on a limited scale. On 20 January 1918, the Council gave directions to the Czechs that they were to move to the Vinnitsa–Mogilyov line and reopen fighting against the Germans. The Czechs, however, refused to move, not least since they were aware that the Ukrainian Government, already operating autonomously from Petrograd, was preparing to declare independence, which duly occurred two days later. The Ukrainian Government promptly headed to Brest-Litovsk to join in the peace negotiations, hoping to secure the creation of a separate Ukrainian state. This left the Allies facing the possibility that a force of some 50,000 men, eager to fight for the Allied cause, would be trapped in Russia. The decision was therefore taken to find some means of withdrawing them, and Trostsky’s willingness to permit the Czechs to leave and join the fighting in France meant that it appeared that the situation might be swiftly rectified. This was an illusory hope.

Japanese cavalry at the charge. Although swept from the close confines of the Western European battlefield by machine guns and fast-firing rifles, cavalry were at times able to come to handstrokes with their long sabres, proving that when conditions were right they still had a part to play.

On 21 March 1918, the Germans moved into the Ukraine, prompting the Czechs to fall back. The Allies then issued instructions to the Czechs, transferring them from the Ukraine to Vladivostok and re-naming them as the Czech Legion. Plans for at least half, and possibly all, of the Legion to leave Russia via Archangel and Murmansk were mooted, since it appeared that the failure to reach consensus over the need for intervention in the far east of Russia would make it difficult to conduct the evacuation from Vladivostok as had been planned. As it transpired, circumstances meant that a withdrawal from Archangel and Murmansk became impractical, not least because of the actions of the Czechs as they sought to escape from Russia.

The Czech withdrawal to Vladivostok depended upon the goodwill of the Bolsheviks, since Russian trains were required to facilitate the movement of the Legion and all its supplies. An initial draft of 70 trains proved inadequate, and more had to be provided. The opening moves of the Legion went reasonably smoothly, albeit slowly thanks to the lack of rolling stock available. The French consul in Vladivostok reported that the first elements of the Legion had arrived there on 28 April 1918. The Czechs discovered that there was no shipping to take them any further, and were left kicking their heels while they awaited transport. The Allied failure to reach agreement on involvement in Vladivostok and the surrounding area now presented a problem, since without consensus on how this was to be achieved, it was unlikely that any ships would be forthcoming. The British refused to send any of their ships for transport purposes, claiming that fighting in the Middle East and maintaining supply routes to India meant that they had none to spare. The French Government was irritated by this, protesting that the British were, in effect, going against the Abbeville agreement by denying the French the use of the Czech troops. This began a process that would finally see a pan-Allied intervention; by the time this happened, though, circumstances had changed dramatically.

Machine-gunners aboard an armoured train. The firepower that could be put down by such a force was awesome, though limited in its reach. An enemy that retreated away from the rail lines was essentially untouchable unless troops capable of fighting dismounted were carried by the train.

At the same time that the Czechs started their journey, the implications of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk wrecked the smooth running of the Czech evacuation eastwards. The peace treaty provided for the return of all German and Austro-Hungarian prisoners of war held by the Russians. Some 800,000 men had to be returned to their homelands, and the Russians sought to achieve this by moving the men by rail. The majority of the prisoners were held in Siberia (with the aim of making escape to friendly territory all but impossible), and this meant that the trains carrying the prisoners had to pass along the same line as those conveying the Czechs. On 14 May, a train carrying members of the Legion stopped at Chelyabinsk alongside a train heading in the opposite direction that was taking Austro-Hungarian prisoners back home. Although the circumstances of what happened next are confused, it appears that the Hungarians shouted abuse at the Czechs, and one of them unwisely threw a missile of some description at the Czech train. The Czechs, who had little regard for the Hungarians at the best of times, responded by dragging the man responsible for throwing the missile away from his comrades and killing him. The local soviet arrested the Czechs responsible for the lynching and took them to the town jail. This was the final straw for the Czechs, who formed up and marched into the town. They then forced their way into the jail, removed their comrades and marched onto the local armoury, removing all the weapons and ammunition they could find. When news reached Moscow, the Bolsheviks arrested the Czech representative there and ordered him to send a telegram to Chelyabinsk appealing to the Legion to lay down their arms immediately. This met with no response. On 23 May, orders were given to all local soviets to disarm the Czechs; unfortunately for the Bolsheviks, they seem to have forgotten that Chelyabinsk was now under the control of the Legion, which meant that the Czechs were running the local telegraph office and saw the instruction. Two days later, Trotsky issued orders that all Czechs seen carrying weapons were to be shot if they refused to surrender. Again, the Czechs read the orders, and this was the final straw, prompting a decision that they should no longer rely upon the Russians, but instead make their own way east, using whatever force was necessary.

The Legion therefore decided that it would fight its way to Vladivostok. Although it was deep within Russia, the Legion was an organized and proficient fighting force, something that could not be said of most of the military forces in central and eastern Russia at that point, most of which lacked the clear aim that the Czechs had set themselves. The Czechs promptly set about taking control of the Trans- Siberian railway, occupying a considerable band of territory either side of the railway line, with the aim of ensuring that the Bolsheviks could not deny them use of this essential transport link. One of the major consequences of this came on 16 July 1918, as the Legion moved towards the town of Ekaterinburg, where Tsar Nicholas and his family were being held prisoner. The Bolsheviks in the town became increasingly concerned that the Czechs intended to launch a rescue attempt, and decided that the royal family had to be neutralized. The family was awoken in the middle of the night and taken to the basement of the house in which they were imprisoned, supposedly to ensure their safety from an imminent attack by the Czechs. When the Tsar and his family were in the basement, the local commissar read out a death sentence and, before the royals could react, a firing squad killed every member of the royal family and a number of their aides.

US troops were committed to the Far East to protect the line of supply and assist the Czech Legion in escaping from Russia. The policy was to try not to escalate the situation, though President Wilson made it clear that other nations were free to do as they thought best.

‘It was left for the Czecho-Slovaks to set the hesitating Allied Powers a shining example, and to lead the way in the task of rescuing Russia. There is nothing more amazing in history than the meteoric insurgence of the Czecho-Slovak troops beyond the Volga and beyond the Urals.’

Lovat Fraser ‘Russia and the Czecho-Slovaks’ from The War Illustrated, 8 October 1918

As the Czech Legion headed eastwards, linking with White Russian forces to aid its passage, a series of bitter battles occurred, notably at Penza on 28/29 May 1918 and in the Volga region, as the Red Army responded to the challenge to the Revolution that the Czechs appeared to present. It now became obvious to the Allies that they needed to intervene in the east to ensure that the Czech Legion could be extricated; the Archangel option was now a non-starter, and only Vladivostok was viable. This meant that the inter-Allied expedition that the British and French favoured was much more likely, since the Americans would, it seemed, have to withdraw their opposition to Japanese involvement as only the Japanese could provide the shipping needed to achieve the removal of the Czechs, and the consequences of giving the Japanese a foothold in Manchuria now seemed less important.

Soldiers of the Czech Legion in Siberia. Although the Czechs had been warned to stay out of Russian affairs they really had no choice but to get involved if they wanted to survive. Control of the Trans-Siberian railway increased their influence upon regional affairs.

The deteriorating situation in Russia finally led to American approval for an Allied intervention at Vladivostok and along the Trans-Siberian railway. President Wilson accepted that a small-scale operation was needed, but made it clear that the United States was opposed to intervention beyond that necessary to help the Czechs and to ensure that former German and Austrian prisoners of war did not interfere with the withdrawal of the Legion from Russia, or take control of military supplies at the port. The Americans would therefore contribute 7000 men for the purpose of aiding the Czechs and guarding military stores. However, while Wilson was clear that a military intervention was undesirable, he made clear in the memorandum that his views applied only to the Americans. The memorandum included an explicit line in which it was made clear that the Americans had no desire to constrain any decisions regarding intervention that were reached by Allied governments.

This gave the Allies a free hand to send troops to Russia, since the utter chaos prevailing in Siberia meant that it would be relatively easy to justify sending a large number of troops to meet the desired aim of the intervention. The Japanese were delighted with the decision, and set about creating an expeditionary force to contribute to the operation, while the British, French and Americans formed rather smaller contingents.

The vast area of Siberia that formed the battlefield for the Czech Legion, White Russians, Bolsheviks and the various Allied intervention forces. Control of the Trans-Siberian railway allowed the Czechs to fight their way towards the port of Vladivostok.

On 3 August 1918, British and Japanese troops arrived at Vladivostok, and the Americans followed on 16 August. The British force, based upon the 25th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment, was the first to move into position, having been asked by the Czech representative at Vladivostok for assistance in a battle that was taking place on the river Ussurie. Czech and Cossack troops were facing a strong force of Bolshevik troops, which was rumoured to be led by German and Austrian officers. The commanding officer of the Middlesex, Lieutenant-Colonel John Ward, sought permission to send half of his battalion to help, and the War Office gave permission. Ward took 400 of his men and a mixed force of Czech infantry and Cossack horsemen to the front line. After a fortnight of waiting, Ward received news that a contingent of French troops would be arriving in due course, and that the Middlesex would come under the command of the French officer. However, just as the French arrived, the Bolsheviks launched an attack and sought to outflank the Allied positions. The action began with combat between two armoured trains, one Bolshevik the other British manned, and the Bolsheviks were able to manoeuvre into a position that threatened the Allied lines. A battalion of Japanese troops was sent from Vladivostok, along with an artillery battery, and they helped to stabilize the situation. Ward’s next set of instructions revealed the depth of the Japanese commitment in Siberia, since he was told that an entire Japanese division would be arriving in due course, and that the Middlesex battalion would come under the command of the Japanese commander, General Oie. The Japanese division arrived on 22 August, and Oie decided that the main attack would be conducted by his troops and the Middlesex, supported by the French and the Czechs. The British soldiers were highly impressed with the quality of the Japanese troops, and the Bolsheviks were routed. Following this success, the Allies moved along the railway to positions at Omsk. The British left Vladivostok on 24 September and took up their new positions a month later.

It soon became clear that the Japanese regarded their allies with nothing more than polite tolerance (and occasional obstruction), seeing them as an obstacle to Japanese occupation of eastern Siberia. To complicate matters for Ward and his men, the local government at Omsk was promptly deposed in a coup, with Admiral Kolchak being appointed as Supreme Governor of the area. Kolchak managed to bring some degree of organization to the White Russian forces, and they enjoyed a number of successes, finally managing to reach a position only 480km (300 miles) from Petrograd. However, the Czechs despised Kolchak, and he was unable to make any use of the Legion as it headed towards Vladivostok.

Lieutenant-Colonel Ward of the Middlesex Regiment was forced to operate in a complex political environment. He led part of his force to the assistance of Czech and Cossack forces fighting in Siberia, and later fought under the command of a Japanese general.

By March 1919, the Allies had over 100,000 men in Siberia, dominated by the Czech Legion with 55,000 men, and an ever-expanding Japanese contingent that would eventually reach a strength of 70,000. However, by this point, only the Japanese Government remained enthusiastic about the commitment to Siberia. The British, American and French governments faced increasing pressure to withdraw from a commitment that was little understood and even less appreciated by their electorates. The Czechs and Slovaks had been granted their homeland in the peace treaties that ended the war, and their only motivation was to leave Russia for their newly created state. Suspicions about Bolshevik cooperation with the Germans were now irrelevant to them, and the Allied powers had little to concern them with regard to the progress of the war, even though they hoped that the Bolsheviks might be overthrown. By early 1919, then, the lack of a clear end-state for the Allied mission, coupled with the fact that a quick end to the Civil War appeared unlikely, led to a situation where the Allied powers were more than willing to extricate themselves from Russia.

With the main objective behind Allied intervention in Russia being to attempt to renew an Eastern Front against Germany, it was perhaps inevitable that there would be an intervention in South Russia. There were a number of generals in the Russian Army who thought that it was in the nation’s interests to continue to fight, recognizing that hopes of creating a greater Russia would disappear once a peace treaty was signed with Germany. Whether the Allies or the Central Powers won the war, the conclusion of a separate peace would leave Russia without a meaningful voice at the conference table, and the dissident generals felt that it would be a failure of duty if they did not attempt to continue the war – a step that would inevitably require the defeat of the Bolsheviks. A further factor in South Russia came in the form of the Cossacks, who could not accept the notion of a Bolshevik-run country, and who were eager to see the removal of the new regime.

A number of prominent Tsarist generals managed to flee from Petrograd and Moscow in the aftermath of the revolution, notably General Alexeev, who had been the Tsar’s chief of staff, and General Kornilov, leader of the failed coup against Kerensky. Both reached south Russia in December 1917 and established a ‘Volunteer Army’. The Cossacks were unimpressed with the new arrivals, feeling that they would interfere with their ability to run their own affairs, not least because the Bolsheviks would attempt to suppress any counterrevolution. Furthermore, Kornilov and Alexeev were not of the same views about how to overcome the enemy, and it took careful discussions led by Alexeev’s chief of staff, General Denikin, to create a joint position, which was articulated in January 1918. The two generals made clear that the Volunteer Army would defend south and southeastern Russia against armed invasion, be that by the Germans or the Bolsheviks. To ensure that the Cossacks remained supportive, Kornilov and Alexeev agreed that General Kaledin, the elected Cossack leader, would remain in control of all aspects of Cossack affairs. Alexeev would oversee administration of the Volunteer Army and relations with the Allies, while Kornilov would be responsible for commanding the army itself.

The British sent assistance to White Russian forces fighting in the south of the country, arriving in November 1918. It was hoped that British, French and other Allied forces could shelter those opposed to Bolshevism while they formed an effective army to retake the country.

Most military revolvers of the period used the same swing-out cylinder loading method. Cartridges were pushed out of the cylinder using the ejector rod under the barrel. Note the attachment point for a lanyard at the base of the handgrip.

The Volunteer Army gained an early boost when the British Government decided that it would support it. The death of Alexeev from a heart attack and Kornilov’s loss in action in April 1918 meant that Denikin assumed command of the White forces in South Russia. The initial success he enjoyed encouraged the Allies, particularly the British, who sent him a military mission to provide advice and to coordinate the provision of equipment. This mission arrived on 26 November 1918.

Thirteen days before, the British and French ended the coordination of their operations in North and South Russia. The British hoped to retain their bases at both Murmansk and Archangel, with the hope that they would remain until the Bolsheviks were overthrown. The French Government also held optimistic hopes for its position, aiming to create a border between Riga and Odessa over which the Bolsheviks would be unable to cross. French naval units were given orders to transport troops to Odessa, as a precursor to the arrival of two divisions of Greek troops. At a conference arranged by the French, pro-Allied Russian groups were informed that the Allies would restore order in Odessa and provide the volunteer Ukrainian Army with protection from Bolshevik attack while they trained in preparation for an offensive of their own. The pro-Allied groups agreed to support the French and British in restoring Russia to its pre-1914 borders (with the exception of territory in Poland). The conference also led to agreement that Denikin would command the White Russians, thus bringing a unified command structure to the anti-Bolshevik forces.

The plan suffered an immediate setback when Ukrainian nationalists staged a coup in Kiev on 17 November 1918, declaring independence. The French now faced the unpalatable prospect that their troops would land in Odessa, only to find it occupied by Ukrainian nationalist forces that would be less than eager to see them, given the French aspiration to recreate a Russian state that contained Ukraine. Negotiations between the French consul, Henno, and the Ukrainian leadership started immediately, and the French diplomat managed to secure agreement that the Ukrainians would not occupy Odessa and oppose the French, thus allowing the landing of French troops and subsequently their allies.

The French then found themselves facing further difficulties when the Peace Conference at Versailles failed to reach any agreement over a unified policy towards Bolshevik Russia. On 22 January 1919, a plan for military intervention by the Allies that had been drawn up by Marshal Foch was rejected. The end result ensured that there would be no coordinated Allied effort in Russia. The failure to agree over a policy created Anglo-French tension. By the time of Kolchak’s assumption of power in Siberia, the French had grown to mistrust the British to the point where they assumed that the coup that had installed Kolchak had been arranged and supported by the Bolsheviks.

It was also quite clear that while there were a number of pro-Allied groups in Russia, the only common ground between many of the groupings was their shared enmity for the Bolsheviks. Rivalries between various groups were a clear obstacle to success, and the military capacity of many of the White Russian forces was limited.

To complicate matters further, the White Russians were not simply willing to sit back and be given direction by the Allies. After the landing in Odessa, the military governor of the town, General Grishin-Almazov, took the view that he was under the command of General Denikin, rather than the French.

The French were also more than capable of annoying their allies, since an agreement concluded between France and the Ukrainians in March 1919 allowing for an independent state completely compromised the plan for a united Russia. When Denikin protested, he was told that without the Ukrainians the French would have found the prospect of landing at Odessa impossible to achieve. This was perfectly true, since the French forces in Odessa were insufficient to defend against the Bolsheviks. By the end of March, the Bolshevik forces under Ataman Grigoriev were in a far stronger position than the French forces at Odessa. A battle at Berezovka at the end of March ended with Grigoriev’s troops driving the French back and capturing two tanks. A mutiny within the French Black Sea Fleet proved the final straw; the French Government decided that there was little point in remaining in Odessa, since the Bolsheviks were in the ascendency. The French therefore evacuated Odessa at the start of April, and on 5 April 1919 Grigoriev’s troops entered the city.

British officers arriving in South Russia are greeted by General Denikin, who had inherited command of the White Russian forces from Kornilov. The British supported Denikin until 1920, by which time it was obvious that the Whites were doomed to defeat.

While the French had departed, the British chose to remain, and continued to supply Denikin. By March 1920, equipment provided included over 1000 artillery pieces, 100 aircraft and 74 tanks, as well as millions of round of ammunition, engineering and medical equipment, motor transport and uniforms.

By November 1919, Denikin’s forces were in trouble, despite the assistance given by the British, and Prime Minister Lloyd George informed parliament that he had serious doubts as to the viability of Denikin’s aim of establishing a reunited Russia. Naturally, such expressions of doubt by the main source of external support did little for the morale of the White Russian forces. As the Whites finally succumbed, the British advisory units retreated, and it became absolutely clear that there was little point in prolonging the intervention any further.

White Russian troops wearing French uniforms and manning a PM1910 machine gun pose for the camera. Late in 1918 (after the Armistice in the west), French troops were landed in Odessa as part of an Allied joint anti-Bolshevik strategy that failed to materialize.

At a meeting on 4 March 1919, the British cabinet decided that troops should be withdrawn from North Russia during the summer. There was little appetite within the British Government for further confrontation with the new communist regime, and justifying the continued presence of British troops in Russia was becoming increasingly difficult for the Lloyd George administration. To compound the problems for the British Government, by 1919 the intervention had expanded to beyond North Russia, and had become a far more complex political and military situation than had been envisaged. With the threat of the Germans removed, the only way in which the intervention could ever be successful was if the Bolsheviks were removed from power; however, the cost of achieving this seemed far too high, making withdrawal inevitable. As noted above, it took until 1920 before the last British troops left Russia and there were further painful moments before this was achieved. In September 1919, a battalion of Royal Marine Light Infantry mutinied on the Murmansk front, ending with 93 court-martials. In Vladivostok, the withdrawal of the Middlesex Regiment in autumn 1919 meant that there were no troops left to guard the stores. It was ironic, given that one of the reasons for intervention was to protect military stores from the Germans, that the remaining British troops dealt with this problem by taking the supremely practical step of enlisting some of the remaining German and Austrian prisoners of war to fulfil this task. The ex-prisoners, still desperately awaiting passage home and short of food and warm clothing, gleefully accepted the offer of winter clothes and food in exchange for ensuring the security of the supplies. They finally returned home, along with the British, the Americans and the final members of the Czech Legion in 1920. The Japanese, determined to maintain influence in Siberia, remained, but by 1922, public opinion in Japan had turned against the presence of Japanese troops and they too were withdrawn.

Finally, in southern Russia, the reversal of fortune suffered by Denikin’s troops meant that Britain, as the last of the intervening powers to remain, was faced with little option other than to withdraw. As the British withdrew through Odessa, Novorossiysk and, at the very end, from Sevastopol, vast amounts of war matériel were destroyed.

By mid-1920, the Allied interventions had all failed – although as the main aim of intervention had been achieved by November 1918, and given that supporting the White Russian forces was at best halfhearted, this is no surprise. With external powers gone (bar the Japanese in the far east), attention turned to the conclusion of the Civil War and the outbreak of conflict with the newly created state of Poland.

As the Allied intervention gradually disintegrated, troops of various nations were withdrawn through Russian ports and embarked for home. These French troops remain wary even though they are aboard ship; not all of the withdrawals were without incident.