The personnel of the Red Army came from many walks of life. Many were agricultural or industrial workers whose disaffection with their lot in life was sufficient to make them take up arms to change the social order. Some, ironically, came from an army wearied of conflict.

Following their seizure of power in the October Revolution of 1917, the new Bolshevik Government of Russia faced a number of internal and external threats. These included a number of disparate groups that opposed the Revolution and came to be known as the ‘Whites’, as well as the newly formed state of Poland that sought to lay claim to its historic territory in the west of Russia.

The first challenge facing the Bolsheviks in the aftermath of the Revolution was to re-establish an army from the disorganized rabble that much of the Russian forces had become in the last days of fighting on the Eastern Front. In January 1918, legislation allowing any Soviet citizen over 18 to volunteer for the Red Army was enacted and thousands of men volunteered, not least because being in the army offered food and pay. This represented only part of the solution, however, as the recruits could not be considered anything like an effective fighting force, since the training they received was minimal. This was not helped by the lack of competent officers. The policy of allowing units to elect their officers was ill suited to the demands of creating an effective army, since the officers were frequently chosen on the basis that they were unlikely to work their men hard. Many of the elected officers had little military experience and it was no surprise that many Red Army units lacked basic military skills. The Bolshevik leadership became increasingly concerned at the prospect of committing these troops into battle, particularly against disciplined opposition, an increasingly likely prospect as the Allies pondered intervening in the country to reopen the Eastern Front as a peace settlement between the Germans and the Bolsheviks became increasingly likely. Furthermore, the Soviet Government was concerned at the prospect of the Germans going beyond the harsh terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and exploiting Russian territory to support their war effort. In such circumstances, it seemed essential to have an army to attempt to resist such attempts.

Leon Trotsky, founder and commander-in-chief of the Red Army, inspects his troops. The Red Army's system of elected officers was politically necessary, given the sentiments of the time. However, it was not conducive to an effective fighting force and many units were inefficient.

As a result of their concerns, after the signature of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolsheviks appointed Leon Trotsky as War Commissar. A particularly practical revolutionary, Trostksy did not allow high-minded revolutionary ideals to interfere with the process of creating an effective and efficient army. To reimpose discipline upon the Red Army the death penalty was reintroduced, while the matter of providing clear and effective leadership was addressed by the simple expedient of centralizing control of the Red Army and ending the power of local army committees made up of the soldiery. The election of officers was ended, but this created a new difficulty. Although it ensured that wildly unsuitable men were not appointed to command positions, it did nothing to increase the leadership proficiency of the Red Army. Trotsky solved this problem by allowing officers from the Tsarist Army to rejoin the colours, and by conscripting others who had been dismissed or who had resigned in the aftermath of the Revolution. The conscripted officers were left in no doubt that if they attempted to desert their posts, retribution would be exacted upon their families. Many of the returning officers were simply content to be rejoining the army: they had joined the army to serve Russia rather than the Tsar and saw the change in government as being irrelevant to their doing this. By the time Trotsky's recruitment drive for officers was complete, over 50,000 Tsarist officers had taken up positions in the Red Army. Trotsky was well aware that drawing upon former Tsarist officers might be unpopular with the rank and file and his colleagues in government. The latter were relatively easily persuaded of the merits of calling upon the skills of trained officers, while the soldiers’ councils were told that Trotsky was merely using the ‘bricks of the old order’ to help build the new socialist state. To ensure that the newly returned officers did nothing to undermine the Red Army, Trotsky created a cadre of political commissars who were to oversee their actions. The commissars possessed considerable political influence, and in some cases, some commissars began to believe that they knew better than the highly experienced senior commanders in whose headquarters they worked, creating problems as militarily sensible orders were rejected as being counter-revolutionary. The commissar system survived into World War II, and the attempts by militarily incompetent political officers to overrule generals would cause considerable difficulties in the early stages of the German invasion of the USSR. However, in 1918 the step appeared to be a sensible means of ensuring that officers of suspect loyalty were watched and kept on a tight political leash.

Many career officers were entirely happy to join the Red Army as their loyalty was to the army, not the Tsar or any particular political system. Nevertheless the Bolsheviks formed a corps of political commissars to ensure the loyalty of the officer class.

The need for a more effective army was not the only challenge facing the Bolsheviks, since it appeared that there was a danger of a food crisis in the summer of 1918. Having gained much of their popularity with their pre-revolutionary promises of a greater supply of food for the population, the Bolshevik leaders were painfully aware of the possibility of a lack of food undermining their support and creating a situation that might be exploited by pro-Tsarist forces. As a result of these concerns, the Bolsheviks attempted to impose greater control over the countryside, with the appointment of so-called ‘committees of poor peasants’ who were tasked with requisitioning grain supplies from farmers. The farmers – the kulaks – were portrayed as enemies of the Revolution, determined to use their control of food to make huge profits at the expense of the urban population and the poor peasants in the countryside. Unfortunately for the Bolshevik leadership, they over-estimated the level of inter-communal tensions in the countryside, where supposed class distinctions amongst the peasantry were unclear and there was little desire to seize food. The end result was the dispatch of parties of workers from the cities to seize food supplies. This did nothing to endear the Revolution to the peasants, many of whom were loyal to the Social Revolutionary Party with its pro-agriculture agenda. As a result of this ham-fisted approach to obtaining greater party control over food supplies, the Bolsheviks alienated the population of much of the countryside. The heavy-handed approach of the requisitioning parties sent from the cities led to such resentment that the peasants began to resist. In the late spring of 1918, risings against the Bolsheviks began, and increased considerably during the summer, to the point that the city of Tambov fell under peasant control until the Red Army restored order. In July, the Social Revolutionary delegates at the Communist Party Congress protested at the way in which the Bolsheviks had implemented their agricultural policy, claiming that the committees of poor peasants were filled with incompetent lazy and unpopular members of the local community who had joined the committees to have power over their neighbours, merely increasing the dislike of other villagers towards them.

Although this map shows neat divisions of territory, with the Bolsheviks in control of the major cities and the Whites pushed back to distant areas of relatively low importance, nothing is ever so neat and tidy. True control over the country took years to establish and required harsh measures.

The Social Revolutionaries became increasingly militant in their views, and shortly after the Party Congress, members of the radical Left Social Revolutionary faction assassinated the German ambassador, Count von Mirbach, in the hope of restarting the war between Germany and Russia. This led to the Social Revolutionaries being expelled from the soviets across the country, a move which simply drove them to even more violent acts. A series of abortive uprisings followed, most notably the seizure of the city of Yaroslavl, which held out against the Red Army for a fortnight. This uprising occurred at the same time as the revolt of the Czech Legion, described in the previous chapter, giving further cause in the eyes of the Bolsheviks to murder the Tsar and his family. The Social Revolutionaries’ violent militancy reached its peak with an assassination attempt against Lenin, which came close to success. The assassination attempt led to the creation of an Extraordinary Commission for Struggle with ounterrevolution and Sabotage, otherwise known as the Cheka, headed by Felix Dzerzhinsky. Dzerzhinsky was tasked with launching a ‘Red Terror’, in which the Bolsheviks unashamedly resorted to state terrorism to impose control upon the country, beginning a period of ‘War Communism’ as the government attempted to prosecute a civil war in a climate of increasing chaos.

‘An army cannot be built without reprisals. Masses of men cannot be led to death unless the army command has the death-penalty in its arsenal … Upon the ashes of the great war, the Bolsheviks created a new army … The strongest cement in the new army was the ideas of the October revolution, and the train supplied the front with this cement.’

Leon Trotsky, My Life, Chapter XXXVII

One of the primary difficulties facing the Bolsheviks in terms of establishing their power throughout Russia lay in the fact that they had not seized control as the result of a widespread popular uprising, but in a discrete coup d’état centred around the capital. This left vast swathes of countryside that were, in effect, ungoverned as local soviets attempted to impose Bolshevik rule in the face of opposition from a variety of groups, who ranged from being at best ambivalent about the Bolshevik seizure of power to being implacably opposed and prepared to fight to overthrow the new regime.

Many Tsarist politicians gravitated towards the ‘White’ camp, but it was soon clear that any armed struggle against the Bolsheviks would have to rely upon the skills of the senior army officers who had not committed themselves to the Bolshevik cause. The Whites were united only in that they wished to see Lenin and his government removed from power at the earliest opportunity, and – perhaps to their detriment – had no clearly stated alternative policies to those laid down by the Bolsheviks. Although the Whites were, in general, in accord that Russia should be a republic ruled by a representative government, their leadership failed to articulate this with sufficient clarity, leading to suspicions that the movement was dedicated to the restoration of the Tsar. This provided the Bolsheviks with a useful propaganda tool on occasion, since they were able to present the choice as being between a government of the people (which, it soon became clear, they were not) or a royal government of the sort which had plunged Russia into the chaos in which the country now found itself.

The first military figure of note to be associated with the Whites was the former commander-in-chief of the Tsar's forces, General Kornilov. After the failure of his coup attempt in September, he had been placed under arrest and was in captivity along with a number of other generals. However, his guards were sympathetic, and allowed Kornilov and his subordinates to escape with ease. They headed to Rostov-on-Don to join the Cossack leader General Kaledin, who had successfully resisted all attempts by local Bolsheviks to impose a revolutionary government on the Cossack areas. The failure of the Bolsheviks to penetrate this area meant that the Whites had a convenient base that was relatively secure; all that was required was for the establishment of an agreement between the Whites and the Cossack leadership to ensure that the nascent anti-Bolshevik coalition did not collapse. Even before Kornilov arrived in the Rostov area, General Alexeev, the former chief of staff to Tsar Nicholas and commander-in-chief of the army at the beginning of the Provisional Government, set about establishing the forces necessary to both support the Allies by reopening the Eastern Front and to resist the Bolsheviks. Alexeev's early attempts were reasonably successful in bringing together some fighting forces, but it took the arrival of Kornilov and the issuing of a general appeal for volunteers in early January 1918 for the Whites to begin recruiting in numbers. Even then there was a problem, since it was inevitable that many recruits would have to be drawn from the local peasantry – but relations between the Cossacks and the peasants were poor, and Kaledin was faced with the considerable task of attempting to win the peasants around.

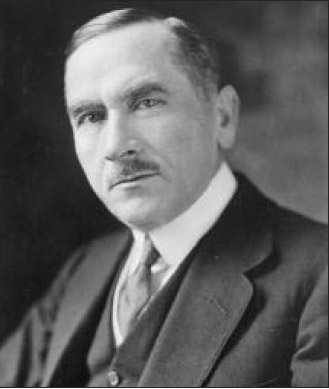

General Mikhail Alexeev's career as an anti-Bolshevik leader was marred by his difficulties in cooperating with Kornilov. Alexeev had served as the Tsar's chief of staff, before performing the same role for the Provisional Government following the Tsar's abdication

Despite Kornilov's arrival increasing the number of volunteers for the Whites, it soon became apparent that there was a problem: out of the first 3000 men to sign up for the Volunteer Army, all but a dozen were officers. This created a situation in which the men who had previously commanded platoons, and sometimes even regiments, in the old Tsarist army found themselves fighting as ordinary soldiers with no leadership responsibilities, something with which they were most uncomfortable. Kornilov was anxious to ensure that his army was led by the most capable men, but this created difficulties when officers refused to serve under men who had been promoted above them on merit. Those officers who wished to see the restoration of a monarchical government could not be persuaded to serve under officers who were in favour of the creation of a constitutional monarchy, while others, finding that they could not serve with their previous rank and privileges, decided not to participate at all.

White recruits wearing British uniforms and serving an Austrian Schwarzlose machine gun (left). Many of the recruits to the Volunteer Army were officers, which meant that many had to accept the role of common soldiers, which did not please them at all.

If this was not enough, the Whites were seriously hampered by a lack of cooperation between the generals. Alexeev had established himself as the commander in Rostov and was not prepared to subordinate himself entirely to Kornilov. The end result was a messy compromise in which Kornilov had command of the Volunteer Army, but Alexeev had control over all political matters and the business of financing the army. This division of command was ineffective, hampered by the fact that Kornilov and Alexeev spent much of their time arguing over what the Whites should do. The situation reached its nadir when the two men stopped talking to one another, bringing the Volunteer Army to a grinding administrative halt as contradictory orders and instructions were issued. Alexeev and other White generals regarded Kornilov with a mixture of disdain and distrust. They thought he was little more than a populist rabble-rouser, concerned more with cementing his own popularity and position; adding to their low opinion was the fact that he had risen to high rank quickly and was therefore younger than many of the senior officers he had overtaken on his way to the top. However, none of the distrustful generals could deny that Kornilov was highly popular, and this meant that he had to be tolerated, since he could command the respect of those who would be doing the fighting to a far greater degree than perhaps any of the other White generals in the Don region.

White Russian infantry in training. The two nearest the camera have rolled blankets slung across their bodies. A few personal items could be carried this way if a knapsack was not available, and the blanket theoretically offered a little protection from a cavalryman's sword stroke.

To make matters worse, relations between the Whites and the Cossacks were tense. The Cossacks were far from united in their views on the Revolution, and many of them were tired of fighting, having seen active service since the outset of World War I. A strong body of opinion existed in favour of seeking some sort of accommodation with Lenin and his followers, but this was counterbalanced by views from Cossacks living in South Russia, who were concerned that the Bolsheviks would remove long-standing Cossack privileges over land so that it could be given to the peasants. Cossacks from the north resented the wealth of those living in the south, and were unhappy at the way in which Kaledin had given the impression that the Cossacks were united behind him. Many Cossacks living in the northern Don region sided with the Military Revolutionary Council led by Philip Mironov, who wished to see the creation of an independent socialist Cossack republic. To complicate matters further for the Whites, they discovered that most of the inhabitants of the Don cities were in favour of the Bolsheviks. As a result, factory workers staged a number of strikes, which the Whites unthinkingly put down with considerable vigour. The repressive response only confirmed the views of the workers, who moved from striking to killing anyone suspected of being a supporter of the White movement. The White response was even more brutal, and within a matter of weeks the Don region, at least in its urban areas, was on the brink of civil war.

Officer cadets of the Volunteer Army. As the support of the Cossacks faded away, Kornilov's Volunteer Army was shown to be inadequate to the task of keeping the Reds out of the Don region. Fear of failure deterred many potential recruits, further crippling Kornilov's army.

This had a decidedly negative effect on the morale of many of the younger Cossacks, who became increasingly concerned that the presence of the Whites would simply lead to fighting between the Red Army and the Whites in their homeland. Furthermore, having been badly led at the front between 1914 and 1918, most of the younger Cossacks had little desire to fight on behalf of the Whites, who seemed to contain a large number of those who had so badly handled the fighting against the Central Powers. The end result was a division in the Cossack community, followed by the desertion of Cossacks from the Whites. The defence of the Don region increasingly fell upon Kornilov's Volunteer Army, bolstered by a few remaining Cossacks. Alexeev's efforts to find funding for the Volunteer Army had borne little fruit, and by late January 1918, the local population, including members of the middle classes who might have been thought likely to support an anti-Bolshevik movement, were showing signs of hostility to the Whites. One of the reasons for this lack of local support may have been a growing appreciation amongst the locals that the Volunteer Army was most unlikely to be able to resist an attack by the Bolshevik forces, and that it was better to hope that the failure to find support would drive the Volunteers away.

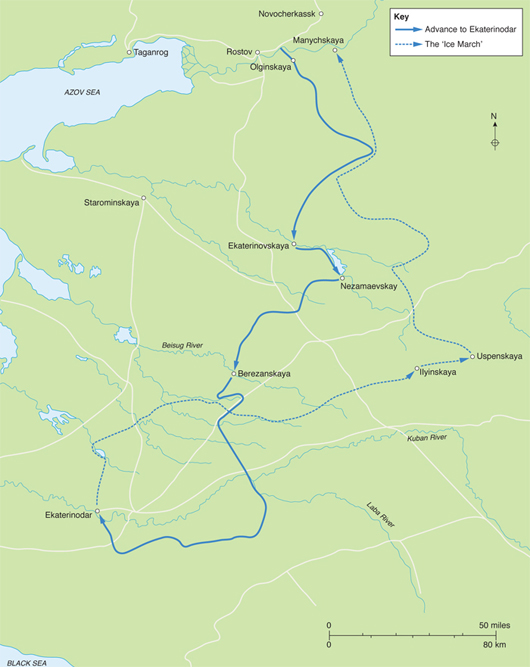

On 2 February 1918, the workers in the city of Taganrog rebelled against the Whites. The Red Army moved in six days later, prompting the rapid retreat of the few remaining Volunteers in the city, who headed towards the much more important town of Rostov. It seemed pointless to allow the Bolsheviks to destroy the Volunteer Army around Taganrog, leaving the heartland of the Whites in the south at the mercy ofthe enemy. Kornilov hoped that the withdrawal of forces back to Rostov would be accompanied by an agreement with the Cossacks to stand against the Reds. This was optimistic; on the same day, Kaledin, feeling that the situation was hopeless, submitted his resignation as Cossack leader. Having laid down his office, he shot himself. The Whites in South Russia were now on the point of disintegration, as the Reds advanced on Rostov and took it on 23 February. The capital of the Don region, Novocherkassk, fell two days later. Lenin claimed that the Civil War was over, since only a small pocket of resistance remained. In fact, he was being decidedly optimistic, since, in defeat, the Whites finally began to coalesce into a recognizable opposition. As the Red Army advanced on Rostov, Kornilov led the Volunteer Army out of the Don with the aim of making the Kuban. The resultant retreat became known as the ‘Ice March’, and served as a rallying point for the Whites. The Volunteer Army marched deep into the steppes, pillaging from peasant communities on the way, and committing a variety of atrocities against the peasantry simply on suspicion that the locals were likely to be Bolshevik supporters. Eventually, the Ice March reached the vicinity of Ekaterinodar, the capital of the North Caucasian Soviet Republic, and were joined by the Kuban Army of over 3000 Cossacks. The Kuban Army had not planned to meet with the Volunteers, but almost literally bumped into them as they retreated from Ekaterinodar. Kornilov decided that with 7000 men under his command, he should attack the city. This was a ridiculous proposition, since his force was outnumbered by more than two to one, yet he persisted, even after the failure of the first assault on 10 April. It appeared to his subordinates that Kornilov was about to embark upon a course of action that would lead to the complete destruction of the Volunteer Army and the allied Kuban Army. Perhaps fortunately for the Whites, but distinctly unfortunately for Kornilov, the Red Army shelled his headquarters on the morning of 13 April, and he was killed by a direct hit on the building he was in.

Denikin helped form the Volunteer Army and commanded it after Kornilov was killed in April 1918. He led the last White offensive towards Moscow in 1919.

Denikin was born in December 1872, the son of a retired Russian officer and a Polish mother. He grew up in reduced circumstances, with his father's pension being barely adequate to sustain the family. Denikin followed in his father's footsteps, attending military college in 1890, and graduating as an officer two years later. He saw active service in the Russo-Japanese War, and rose through the ranks until, by the outbreak of World War I, he was a major-general commanding the Kiev military district. He then took over as deputy chief of staff of the Russian Eighth Army and was then given command of the 4th Rifle Brigade. In 1916, he was posted to command VIII Corps, and led his troops in Romania during the Brusilov Offensive. After the revolution, he supported the attempted coup by Kornilov and was imprisoned as a result. He escaped, along with Kornilov, and joined the White forces, taking command after Kornilov's death. He resigned from his post as the Whites in South Russia teetered on the brink of defeat, and went into exile along with many other senior White officers.

He lived in France from 1926 and, unlike Wrangel, played no part in attempting to agitate against the Soviet regime, although this did not prevent Stalin from ordering a failed attempt to abduct him from Paris and return him to Moscow for trial. After France fell to the Germans in 1940, he went into exile in the French countryside and refused all efforts by the Nazis to use him for anti-Soviet propaganda broadcasts; appalled by the Nazis he in fact gave support to his local resistance movement. At the end of the war, concerned at the prospect that the Russians might demand his return, Denikin left France and took up residence in New York. He died in the United States in August 1947 while on holiday. He was buried in Detroit, but in 2005, President Vladimir Putin gave permission for his remains to be re-interred in Russia. They now lie in the Donskoy Monastery in Moscow.

In the immediate aftermath of World War I, weaponry was not a problem for either side. Small arms in particular were very easy to come by but even artillery, like this 4.5in howitzer, was relatively simple to obtain. As a result both sides were able to field effective conventional forces.

As the situation deteriorated and the local population turned against them, the Volunteer Army retreated southwards. Although Lenin thought that theWhites were finally beaten, in fact this period marked their emergence as a much more effective fighting force.

Kornilov was replaced by General Anton Denikin, who ordered an immediate withdrawal. The Volunteers paused only to bury their fallen leader, and resumed the Ice March, heading back towards the Don. The Red Army chanced upon Kornilov's grave as they pursued the retreating Whites, and stopped for a macabre celebration in which they desecrated Kornilov's grave and defiled the corpse, a process that allowed the Volunteers to put enough distance between them and their pursuers to make it impossible for the Bolsheviks to catch them. Over the course of the 1120km (700-mile) retreat, the Volunteers suffered heavy losses to the cold, but this time found that their columns were joined by volunteers, many of whom had seen the full brutality of the ‘Red Terror’ and who decided that while the Whites were brutal, they were a preferable option to the Bolsheviks. When Denikin's force finally arrived on the Don, its ranks had been swelled considerably; more importantly, the rigours of the Ice March and the experience of battle against the Reds had fostered a fighting spirit that had been signally lacking when the Volunteer Army formed. Just as Lenin and the Bolsheviks thought that the war was over and the Whites in the south destroyed, the situation changed. Over the course of the next few months, the Bolsheviks managed to aid the Whites into turning into a truly credible force.

The reason for this lay in the way in which the Bolsheviks had behaved in the Don region. The Don Soviet Republic behaved with incredible barbarity towards the local population. Food was requisitioned from the peasantry, priests were murdered and hundreds of hostages were taken and then shot. The area was inundated with Red Army troops as they withdrew from areas being occupied by the Germans under the provisions of Brest-Litovsk, with the end result that the locals in the Don were subjected to a wave of terror that drove them to open revolt. A series of Cossack risings followed, and within a month, there were at least 10,000 Cossack cavalrymen determined to fight the Bolsheviks under the leadership of the new Ataman, General Krasnov. In the first week of May 1918, Novocherkassk was taken, and within six weeks, Krasnov found himself at the head of an army 40,000 strong. Finding weapons and supplies for the army was easy, since the Germans were happy to provide rifles, ammunition and other military matériel in exchange for wheat.

The British Webley-Fosbery revolver as used in Russia and elsewhere during World War I. Reloading a revolver was normally a fairly slow business. One solution was the fore-runner of the modern speedloader. This example refills all six chambers at once.

However, Denikin seemed curiously eager to maintain the Whites’ record of never missing the opportunity to miss an opportunity, and instead of allying with Krasnov's forces for a drive on Moscow, which might well have led to the collapse of the Bolsheviks, he led his army south to the Kuban steppe, intent on building up a large army of his own. In this nregard, he was successful. As the Volunteer Army marched south, it attracted increasing numbers of recruits, many of whom were locals who had seen the brutality of the Bolsheviks at first hand and who were now implacably opposed to the Revolution. By August 1918, Denikin had a formidable army nearing 40,000 strong, which he used to capture Ekaterinodar, driving the Reds out of the Kuban region. By the winter, Denikin found himself in complete control of the White Army in the south, leading a battle-hardened force that controlled a substantial area of countryside. He was also undisputed leader of the Whites: Alexeev had died in October 1918, and this meant that the problem of divided command in the Volunteer Army was finally overcome. However, despite this unexpected upturn in theWhites’ fortunes, there were still fundamental problems that would, in the end, contribute to the final failure of their quest to remove Lenin from power. Denikin and his subordinates did not fully understand that the Whites were not just a military force, they needed to establish political structures that would enable them to govern the territory under their control. This lack of political awareness was to become an increasing problem in 1919, since relations between the Whites and the Cossacks deteriorated, not least because the Cossacks were most reluctant to move away from their homelands to fight the Bolsheviks. To make matters worse, the Cossacks continued to ignore the need to earn the support of the peasants; if anything, the behaviour of their troops in peasant villages did much to turn support away from the Whites as the longsuffering rural population struggled to decide which side was the lesser of two evils and decided that it was, perhaps, the Bolsheviks.

Although a popular stereotype of the Cossack as a wild tribesman exists,most of those that served the Russian military wore uniform and served in trained cavalry units. Cossack units inWhite Russian service often included a mix ofWorldWar I veterans and new volunteers.

Despite this haemorrhaging of support thanks to the behaviour of the Cossacks, Denikin's forces began 1919 with a series of significant victories over the enemy. The Volunteer Army, now renamed the Armed Forces of South Russia, began to enjoy some aid from the British, and was vastly increased in size compared to its parlous state just after the Revolution. In May and June 1919, the Whites in southern Russia met three Bolshevik armies and soundly defeated all of them, giving them control over a large area stretching from Kharkov in the Ukraine through to Tsaritsyn on the river Volga. At this point it seemed that the White forces under Admiral Kolchak in the east might be able to link up with Denikin, but the opportunity soon passed. Denikin abandoned ideas of forcing a link with them and instead ordered a march on Moscow. He planned an advance along three main axes: units under General Wrangel would advance along the Volga; General Mai-Maevsky would attack from Kharkov, taking Kiev as he went; while General Sidorin was to attack from the Whites’ positions around Rostov.

By the end of August 1919, the offensive had enjoyed considerable success along its western flank, and a number of major towns and cities were under Denikin's control, including Odessa and Kiev. The Bolsheviks attempted a counter-offensive, but this was halted. The Whites took Kursk in September, followed by Voronezh and Chernigov in October, successes swiftly followed by the Bolsheviks losing Orel and lead elements of the Whites reaching Tula, the last major city before Moscow. Meanwhile, in the north, General Yudenich's Northwestern Army looked to be on the verge of seizing Petrograd. It seemed that the two major Russian cities might fall at any moment to the Whites; but the impression was illusory. Yudenich's forces were repulsed by Bolshevik units under Trotsky's command and by early November were back at their start line.

In a civil war where the support of the general populace was of critical importance, the behaviour of Cossack troops towards the peasant population was counterproductive to the anti-Bolshevik cause.

Denikin's forces, meanwhile, had reached their culminating point and were in no position to go on. Their supply lines were over extended, and the length of the front was such that forces were thinly spread. On 20 October, the Bolsheviks retook Orel, and Voronezh fell to Red Army forces under Marshal Budenny. The central sector of the White front became increasingly disorganized as General Mai-Maevsky, already known for his excessive drinking, spent increasing amounts of time viewing the world through the bottom of a vodka glass instead of maintaining discipline amongst his troops, leading to his dismissal and replacement by Wrangel, who had the thankless task of restoring the fighting power of the forces in the centre. However, his arrival came too late to save the situation. The Bolsheviks exploited the failure of the Whites to win the support of the peasants, and, as the Red Army advanced, it created units of partisans drawn from the peasantry to attack the Whites in rear areas and disrupt what was turning into a retreat. In December, the Bolsheviks reoccupied the Ukraine, and the Whites were in danger of being overwhelmed. Finally, in January 1920, the Whites made their last stand around Rostov, but the position was hopeless. Falling back on the port of Novorossiysk, Allied ships helped to evacuate his forces into the Crimea, whereupon Denikin resigned his command in favour of General Wrangel in March. Wrangel set about rebuilding his forces. A capable leader, Wrangel won a few local victories against the Red Army to the extent that the French were moved sufficiently to recognize him as leader of South Russia. However, this moral support was not accompanied by any munitions or equipment, which left the Whites in an extremely difficult position.

Wrangel was born into a Russian family of Germanic origins in 1878. After graduation from the Institute of Mining Engineering in 1901, he sought a commission in the Russian Army, joining the cavalry in 1902. He fought in the Russo-JapaneseWar of 1905, and participated in the punitive expedition in the Baltic during the following year. After staff college, he undertook a number of command appointments, culminating with the leadership of a cavalry corps duringWorldWar I.

After the Bolsheviks seized power,Wrangel went to the Crimea where he joined the Volunteer Army. He was given command of a cavalry division, before taking command of the Caucasus Army. His troops captured Tsaritsyn in summer 1919, and he became commander of the entire Armed Forces of South Russia in March 1920 after Denikin's resignation.

A series of defeats at the hands of the Red Army forced him to retreat to the Crimea, and he evacuated his army along with all the civilians who wished to accompany him. His status as the last White commander meant that he was perhaps the most prominent Russian exile of the 1920s. He died in 1928, with claims by some members of his family that a Soviet agent poisoned him.

There was one final hope for the southern Russian Whites, and this came thanks to the Russo-Polish War. While the Bolsheviks were distracted with the fighting against the Poles, Wrangel took the opportunity to launch a new offensive on 6 June 1920, breaking out of the Crimea. The Kuban was invaded in August, but Wrangel was forced to evacuate. The final blow came when news of the Russo-Polish armistice arrived. The Bolsheviks were now able to turn their full attention to dealing with the Whites in the south. On 28 October 1920, the final Bolshevik attack began, and the Whites were forced to fall back into southern Crimea. The position was now hopeless, and the Armed Forces of South Russia were evacuated to Constantinople, where it disbanded. The Bolsheviks were faced with the need to deal with a few remaining troubles in the east, and with a variety of separatist movements, but to all intents and purposes the Civil War was at an end.

The emergence of White forces in South Russia was soon followed by the creation of similar units in the east. This owed much to the Czech Legion's attempts to return home, as described in the previous chapter. In the chaos caused by the fighting between the Czechs and the Bolsheviks, local leaders proclaimed Siberia to be an autonomous state. On 30 June 1918, a Siberian Government was created under the leadership of Pyotr Vologodsky. Vologodsky suppressed the local soviets and began the creation of an anti-communist army. This was not the only government, however, since the Social Revolutionaries established an administration of their own in Samara. The two administrations co-existed, but news of the Bolsheviks’ retaking of Kazan in September 1918 led to a compromise agreement under which the Siberian Government and the Samaran ‘Komuch’ combined to form a supposedly ‘national’ government at Omsk, known as the Directory. The Directory was beset with political wrangling between moderate and conservative factions, but both sides agreed upon the appointment of the recently arrived Admiral Alexander Kolchak as war minister. Kolchak had been the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, and had gone to the Far East after the Revolution. He was on his way to join the Whites in South Russia when the invitation to be war minister for the Directory was issued. The conservative faction in Omsk launched a coup against the Social Revolutionary members of the Directory on 18 November and imprisoned them; they promptly offered Kolchak the position of Supreme Ruler and commander-in-chief of all Russia. Kolchak accepted, although the creation of the position was a source of some confusion, since the White forces in southern Russia were not minded to take orders from someone appointed without the slightest reference to them.

Neither side was sufficiently well organized to be able to deploy large, well coordinated forces in all areas.However, even a relatively small garrison, such as this Red Army force with its makeshift barricade, could hold a town against most opposition with a few well sited machine guns, freeing more men for operations elsewhere.

The activities of the Czech Legion in the east contributed to a separatist movement in Siberia and the formation of a government there. The Czechs’ control of the Trans-Siberian railway was of great importance to this region, and their influence on local affairs was considerable.

Kolchak was born in 1874 in St Petersburg, the son of a naval officer. From an early age it was clear that he was going to follow his father's career, and he attended naval college, graduating in 1894.He was posted to Vladivostok in 1895 and served there until 1899, when he was sent to Kronstadt. While there, he joined a Polar expedition in 1900 as the expedition's hydrologist. Kolchak returned to Kronstadt in 1902, but was to participate in three further Arctic expeditions.

Kolchak was sent to Port Arthur during the Russo-Japanese War, and commanded the destroyer Serdityi, which sank the Japanese cruiser Takasago. Wounded during the siege of the port, he was taken prisoner, but poor health meant that he was repatriated before the end of the conflict.

Kolchak was a leading figure in the rebuilding of the Russian Navy after the disaster of the Russo-Japanese War and by 1916 he had been promoted to the rank of vice-admiral, the youngest admiral in the Russian Navy. Kolchack was given command of the Black Sea Fleet, but although the fleet participated with some success in operations against the Turks, it collapsed into revolutionary chaos in 1917. Kolchak was removed from command and sent to Japan as a military observer, and was still there when the October Revolution occurred. He was persuaded to join the White Russian forces, but while on his way to South Russia, he was persuaded to join the anti-revolutionary Directory Government at Omsk. Appointed to supreme command after the 18 November coup against the government, Kolchak instituted a military dictatorship and enjoyed some initial success against the Bolsheviks. However, it was not long before the tide turned, and the Whites in Siberia were forced into retreat. By the end of 1919, the Bolsheviks were on the verge of victory, and Kolchak left for Irkutsk. However, his poor relationship with the Czech Legion led to his being handed over to a new revolutionary government in Irkutsk in exchange for the Czechs being given uninterrupted passage to Vladivostok. Kolchak was arrested and the new government began interrogating him in preparation for trial; however, the process was circumvented when orders arrived from Moscow that Kolchak should be executed immediately. He was shot by firing squad in the early morning of 7 February 1920, and his body dumped in the river Ushakovka.

Kolchak's experience as a naval officer meant that he did not fully understand the dynamics of land warfare, and this created a number of problems when it came to planning campaigns. He was also an unskilled politician, and relations between Kolchak's forces and the Czechs began to deteriorate. To complicate matters further, the way in which Kolchak had assumed power had created dissent amongst the anti-Bolshevik forces; one month after his taking office, the local Social Revolutionaries staged a counter-coup attempt against him. This failed, but a number of the Social Revolutionaries abandoned him and changed sides. Kolchak determined that it was necessary to begin his military campaign against the Bolsheviks in a bid to distract from the political situation and, initially, these operations went well. The Siberian armies, commanded by the Czech General Gadja, took a number of towns and cities, and Kolchak hoped that it might be possible to link up with the White forces cooperating with the Allies at Archangel. To this end, Gadja pressed onwards, taking the town of Galzov by the end of April 1919. However, the Bolsheviks launched a counter-offensive under Mikhail Frunze, which swiftly drove the Whites back. The Bolshevik leadership decided that it would press on with the pursuit of Kolchak, and he was forced to retreat. This meant that Kolchak had to abandon plans to join with the other White forces in Russia. Driven back into Siberia, Kolchak dismissed the commander of his army, General Diederichs, when he suggested the evacuation of Omsk. On 14 November 1919, it proved necessary to follow Diederichs’ advice anyway, and the city fell to the Bolsheviks. At this point, the Whites in the east had lost all confidence in Kolchak, and he attempted to leave Siberia for Irkutsk, where his cabinet awaited him. They were overthrown by an Social Revolutionary-dominated group, and this prompted Kolchak to resign in favour of Denikin on 4 January 1920. Kolchak now attempted to reach Irkutsk, where he hoped to seek sanctuary with the British military mission. However, the Czechs, seeing the opportunity to gain safe passage from Siberia, handed him over to the administration in Irkutsk. The Irkutsk Government was replaced by a Bolshevik soviet on 21 January, and Kolchak was summarily executed by firing squad on orders from Moscow, without even a show trial. The Czech Legion finally left for home, and the resistance to the Bolsheviks in the east ended, leaving the Whites in the south to struggle on for a few more months until they, too, were forced to abandon their efforts in October. The Bolsheviks successfully mopped up resistance from a variety of anti-communist groups and peasant councils, and by the end of 1921, the Civil War was over. Bolshevism had triumphed, and it could be said that at long last, the trauma of World War I was at an end for Russia.

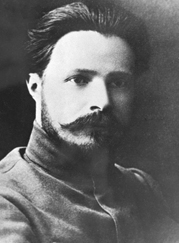

Jozef Pilsudski always believed that Poland's independence could only be won by force of arms. He formed what amounted to a private army, fighting on the side of the Central Powers. His forces later fought the Russians during the Russo-Polish War.

The seeds of further trouble were sown when the Versailles conference gave Poland territory that had been part of Russia for a century. Russia was in chaos at the time and unable to do anything about the decision, but once the Civil War was over, the situation was very different.

The establishment of a Polish state in the aftermath of World War I represented the realization of a long-held set of aspirations of the Poles, particularly the social elite, which (in various forms) had been attempting to create an independent Poland for two centuries. In the eighteenth century, Poland had been partitioned between Russia, Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Poles had fought to re-establish their nation ever since. World War I brought about their best opportunity for years. The principle laid out by the Allied powers that peoples should be granted self-determination meant that it was almost inevitable that the defeat of Germany and Austria-Hungary would lead to the establishment of a new Poland. The situation, however, was complicated by the fact that the Poles desired territory that had been part of Russia for over 100 years by the time that the Versailles peace settlement was signed. The utter confusion that existed after the Bolshevik Revolution meant that it was impossible to determine the border between Poland and Russia at the peace conference. This in turn meant that the Poles’ perceived a window of opportunity that could be exploited to their advantage, both to regain historic Polish lands and ensure that the reformed Polish state enjoyed a level of security that it had not enjoyed in the eighteenth century.

The primary weapon of the Russian Civil and Russo-Polish Wars was the bolt-action rifle. This particular weapon is a French Mousqueton Berthier 1890 et 1892 carbine, produced for cavalry and second-line troops. Many examples found their way into Polish hands.

Within the Polish political leadership there were two competing views as to what should be done with the eastern border region. The first point of view, articulated by Roman Dmowski, the leader of the National Democratic Party and founder of the Polish National Committee that had been established in Paris as a means of advocating Polish national self-determination, as well as chief Polish delegate to Versailles, held that Poland should include all the land that had been Polish territory in 1772, regardless of the nationality of those living in those areas in 1919. This perspective was difficult to argue in an atmosphere where the principle of self-determination drove most considerations regarding the redrawing of the map of Europe, but Dmowski was a forceful advocate of the case. However, he did not represent all of Polish opinion.

In contrast to Dmowski, the Polish head of state Jozef Pilsudski felt that it was only appropriate for the non-Polish nationalities living in the Russo-Polish border region to have independent states of their own. He also argued that it was the duty of Poland, as the strongest of the newly created states, to ensure that there was sufficient regional security to guarantee that all the nations in the area remained free, and would not succumb to attack by either a resurgent post-revolutionary Russia or a stronger Germany seeking to re-impose itself upon central and eastern Europe.

Roman Dmowski made a strong argument at Versailles that Poland should be given all the land she had traditionally held (as defined by being Polish territory in 1772) rather than being allocated territory according to whether the population that lived there were Poles or not.

Pilsudski therefore proposed the creation of a Polish-led federation, which would provide the member nations with much greater security. The peace settlement had left East Prussia separate from the rest of Germany, linked only by the soon-to-be-infamous ‘Polish Corridor’, vulnerable to blockage by the government in Warsaw at any time. The Poles were well aware that a recovered Germany might regard this as an unacceptable situation and seek to reverse it by retaking the land removed from it by a peace treaty that was already being referred to as a ‘diktat’ by the Germans, unjust and unreasonably imposed upon the defeated nation.

By contrast, Lenin and the Bolshevik leadership saw Poland as a part of revolutionary theory. Poland represented the land over which the Revolution must cross if it was to be exported. If, for any reason, this proved impossible, it imperilled the Revolution as a whole, since communism would be trapped within the borders of a single nation, vulnerable to attack by capitalist, bourgeois nations anxious to crush Marxism at the earliest possible opportunity. However, the Bolshevik position was not as clear cut as it might seem, since the leadership had given clear statements that it supported Polish independence. However, while supporting the nation's freedom from external rule, Lenin and his fellow communists were simultaneously supporting Polish communists who were anxious to bring about the collapse of the newly formed nation. Pilsudski and many others thought that the Bolsheviks felt that the independence of Poland should be limited, preferring to see the country as part of a wider communist federation that would be dominated by Moscow. The Poles were particularly suspicious of Lenin's intentions in the light of the manner in which the supposedly independent Ukrainian Republic, declared in January 1919, seemed to be completely in thrall to the dictates of the government in Moscow. In addition to this mistrust, the fact that Poland and Russia were historic opponents, with the enmity stretching back to the early years of the seventeenth century, was likely to be a source of tension between the two powers. Thus, by early 1919, the grounds for there being considerable tension between the Poles and Russians were fairly extensive. It would not be long before the tension spilled over into all-out war.

Military operations in Poland made considerable use of armoured cars and motorized transport. The Red Army inparticular developed a number of motorized artillery pieces such as the one shown here.

As the German Army withdrew its positions in Eastern and Central Europe as mandated by the terms of the peace treaty, the Poles moved forces into the borderlands. This was accompanied by the formation of a number of Polish self-defence units in areas such as Western Belarus and Lithuania, as ethnic Poles sought to create organizations through which they might support the move eastwards by Polish regular forces and defend their communities against the possibility of the Bolsheviks taking over. From early January 1919, there were a series of skirmishes between the Polish groups and bands of pro-Bolshevik troops, and from February the situation began to resemble the preparations for war.

The Poles were fortunate in that they had many men who were trained soldiers who could be transformed into an established regular army, but there were some major problems that needed to be addressed. The first was that the Polish Army was made up of a variety of units from several different armies, and there was no real command structure. The cohesion of the Polish Army, at least initially, was based around loyalty to the new nation and to Pilsudski himself. The Polish parliament was faced with the need to bring in legislation to regularize the new army, a task made imperative when Polish units advancing eastwards came into contact with Bolsheviks at Mosty on 14 February. Although the Russian troops withdrew, the two sides took up positions so that a nascent front line was in place. On 15 and 16 February 1919, the Poles and the Bolsheviks experienced the first clash of what was to develop into a fully fledged war around the Belarussian towns of Biazroza and Manievwicze. Realizing that the need to establish the Polish Army on a proper footing was now vital, Polish parliamentarians set about creating the legal framework for the new force, and managed to complete the process with the Army Law of 26 February 1919.

At this point, the Poles had some 110,000 men under arms. The nucleus of the new army came from units that had been raised by the Germans in 1917 as they sought more manpower, and which had come under Pilsudski's control in November 1918 with the cessation of hostilities. There were only 9000 men in the ex-German forces, but their numbers received a considerable boost when many of the former members of the Austro-Hungarian Polish Legion (which had been commanded by Pilsudski until its disbandment in 1917) joined the services. Within a matter of months, the Polish Army had increased in strength and was in a position to wage war with the Bolsheviks on a reasonably equal footing. By the end of 1919, a clear front line had developed between the Russians and the Poles, and a series of border skirmishes developed into full-scale warfare as the Poles moved ever further eastwards, faced by an enemy which was hard pressed, dealing not only with the Polish attack but with the efforts of the White Russian forces in north, south and eastern Russia.

The turning point in the Russo-Polish conflict came when Pilsudski's troops began Operation Kiev in April 1920. The Poles hoped that an invasion of Ukraine would allow the creation of an independent Ukrainian state, which would then become part of the planned anti-Soviet federation. Early clashes with the Red Army went the way of the Poles and by 7 May 1920 a combined force of Poles and an anti-communist Ukrainian army had taken Kiev. The Poles began to plan for the next phase of the operation, but were soon met by a fierce counterattack by the Red Army. Polish positions near Ulla were attacked on 15 May by the Russian Fifteenth Army, while the neighbouring Russian Sixteenth Army crossed the Berezina River. Although the Poles were able to throw the attack back, they had to abandon their plans for a further advance. To the north, the Russian counterattack had defeated the Polish First Army, which was forced to retreat. Although the Poles launched a counterattack of their own, they were unable to do anything more than slow down the Russian advance. By the end of May, after fierce fighting, the front had stabilized near the river Auta. Repeated attacks by General Budenny's Cossack cavalry broke the Polish-Ukrainian front on 5 June, and Russian cavalry units poured into the Polish rear areas, causing havoc. The Poles were forced into full retreat, and Kiev had to be evacuated to prevent the forces there from being completely surrounded by the Russians. The Poles stabilized their position in June and attempted a series of counterattacks of their own during the rest of the month and in July, but none of them were successful. However, it appeared that the Bolsheviks had at least been stopped – an optimistic assessment as it transpired.

Frunze was born in Bishkek, the son of a Romanian peasant (originally from Bessarabia). He was an able child, and gained a place at the Polytechnic Institute at St Petersburg. While a student, he joined the Social Democratic Party and became a supporter of the Bolshevik faction. His political activities attracted the attention of the authorities, and in November 1904 he was arrested after a demonstration and expelled from St Petersburg. This did not deter him, and in the 1905 Revolution, he led striking textile workers at Shuya and Ivanovo. He was arrested and tried for his involvement in the uprising and sentenced to death. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment with hard labour, and he was sent to Siberia to serve his sentence. After ten years, Frunze managed to escape to an area where the Tsarist regime had little control, and became the editor of a Bolshevik newspaper. During the February Revolution in 1917, Frunze led the Minsk militia, and was then elected president of the Byelorussian Soviet. He moved on to Moscow, and commanded a workers’ militia unit during the October Revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power.

Frunze was appointed military commissar of Voznesensk Province, and quickly became embroiled in the Civil War. Following his defeat of Admiral Kolchak, he was given command of the entire Eastern Front, and oversaw the final defeat of the Whites in this area. He retook the Crimea in 1920, ending the war in the south, and destroyed the anarchist movement in Ukraine when it refused to amalgamate with the Red Army.

Frunze's success led to his election to the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, and in January 1925 he was appointed chairman of the revolutionary military council. Frunze's time in prison had not aided his health, and he suffered from a weak heart and stomach ulcers. His doctors debated whether or not they should operate on his ulcers, but concluded that this would be too dangerous, since they feared that their patient would not survive the anaesthetic. They were overruled by the Central Committee, and the operation went ahead. Just as the doctors had suspected, the anaesthetic was too much for him, and he died on the operating table on 31 October 1925.

Frunze was buried in the Kremlin wall, and he was recognized with the renaming of his birthplace in his honour (it reverted to its original name in 1991), and the most prominent military academy in Russia bears his name to this day.

Had the Battle of Warsaw ended in the Bolshevik victory it would have become a turning point in the history of Europe, and it is beyond any doubt that with the fall of Warsaw Central Europe would have opened for communist propaganda and a Soviet invasion.’

Lord Edgar Vincent D’Abernon, head of the British Military Mission in Poland

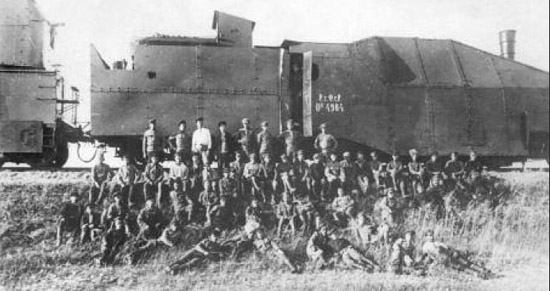

Armoured trains were deployed by both sides in the Russo-Polish War as a means of protecting their rail network and bringing firepower to bear quickly when and where it was needed. This example was operated by the Red Army.

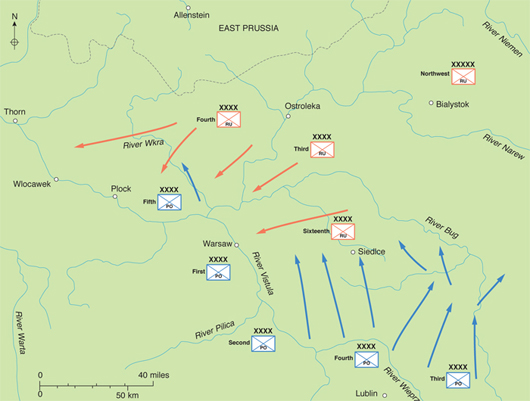

Once the thin Polish defensive line was broken, a desperate scramble to halt the Bolshevik advance ensued culminating in the Battle of Warsaw. The ‘miracle of the Vistula’ saw the Polish forces manage to hold up the Russian advance and then split their armies, forcing them to withdraw.

The Russian Northwest Front, under the command of General Mikhail Tukhachevski, launched an offensive on 4 July 1920, attacking along the line Smolensk–Brest-Litovsk. Although the Poles put up a fierce resistance, they were outnumbered four to one and the Russian numerical advantage told. Within three days, the Poles were in full retreat along the entire front and, by the middle of the month, they had been forced back across the Niemen River. The Russians followed, and it was not long before the retreat resumed once more, with the Russian armies moving at a rate of approximately 32km (20 miles) a day. When the Poles were driven out of Grodno in Belarus, Tukhachevski gave orders that Warsaw was to be seized by 12 August. It seemed that this was perfectly possible when, on 1 August, Brest-Litovsk fell into Russian hands and the last river barriers before the river Vistula and the Polish capital were crossed. By the following day, Russian forces were only 97km (60 miles) away from Warsaw, and it seemed likely that the city would fall to the Russians within a matter of days, a viewpoint given further credibility when Russian Cossack units crossed the Vistula on 10 August, with the aim of driving into Warsaw from the west. Polish resistance meant that Tukhachevski had to modify his planned date for the capture of the city by 24 hours, but was confident of success. However, the initial Russian attack on 13 August 1920 failed. Tukhachevski was unmoved, confident that his superiority in numbers would tell in the end, but his confidence was misplaced.

Soldiers of the Red Army on campaign in Poland. During the drive onWarsaw the Reds became over extended and outran their supplies. Their weariness and disorganization allowed the Polish Army to push the Russians back a considerable distance before a ceasefire was agreed.

On 14 August, the Polish Fifth Army, under the command of General Vladislav Sikorski, launched an attack from around the Modlin fortress area. Bitter fighting ensued for a day, but at the end of the battle, the Russians had been halted. Furthermore, they had lost momentum to the point where the Poles were able to seize the initiative and turn the tables decisively upon their opponents. Sikorski drove his army on, and the exhausted Russians were forced to fall back. On 16 August, Pilsudski launched a counter-offensive of his own, and the Poles were able to exploit a gap between the Russian fronts. The Polish advance continued, wrapping up the flanks of the Russian forces, so that, by 18 August, the majority of Tukhachevski's rear areas were on the brink of encirclement. When Tukhachevski realized what was happening, he gave orders for a withdrawal, but his instructions appear not to have reached many units, which were routed during the course of the next two days. The Russian forces broke down into chaos, and by the end of the month, the prospect of Warsaw falling into Russia hands had passed. The so-called ‘miracle of the Vistula’ raised Polish morale, as did the failure of the Russians to take Lvov. Budenny's army broke off the siege on 31 August 1920, but as he withdrew, his forces were engaged by Polish cavalry in what was possibly the last great cavalry engagement on European soil.

Russian troops, the officers with swords drawn, headed towards the Polish front. The Red Army was forced to fight on several fronts, with major White Russian field forces still in being as well as unrest and insurrection in supposedly cleared territory.

The Polish advance continued, with the Russians suffering further defeats at the Battle of the Niemen River between 15 and 25 September. By the middle of October, the Poles had reached the line Tarnopol–Dubno–Minsk–Drisa, but they were exhausted. The Bolsheviks were desperate to end the war, to allow them to finish dealing with the threat presented by the Whites, and the Poles could go no further. In addition, the Poles were facing considerable pressure from other nations to bring the war to an end, so the Russian offer of peace was accepted, with a ceasefire coming into effect on 18 October 1920. The war was brought to a formal conclusion with the Treaty of Riga on 18 March 1921.