The violence and upheaval of the 1905 Revolution soon passed, leaving the Tsarist system in full control of Russian politics. It was, however, a haunting reminder to many Russians of what might happen if Russia lost another war.

Russia’s defeat at Japan’s hands in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) left her humbled and beaten. The determination of her leaders to return their nation to the ranks of great powers ran counter to massive internal structural problems. Austria-Hungary’s threats to Serbia in 1914 gave those leaders the chance they sought to once again play the role of great power.

There is an old Russian adage that proclaims that Russia is never as strong as she looks, but Russia is never as weak as she looks. In 1914 it was hard for anyone, including the Russians themselves, to know exactly how weak or strong Russia was. Politically the country seemed to have recovered from the revolution of 1905, and the regime of Tsar Nicholas II seemed to most observers to be as solidly in place as ever. Economically, the country remained overwhelmingly agricultural, but it had made some important strides in industrial production in the first years of the twentieth century and was now capable of producing much more of what it needed.Diplomatically, Russia had alliances in place with France and Britain, although the former was both more secure and more important in terms of Russian foreign policy.

Russia’s immense size and human resources made it an ideal ally, especially for France. Sitting on the eastern edge of Germany, Russia provided a massive counterweight, distracting German attention away from France. Over the years, the French had repeatedly urged the Russians to agree to aggressive, offensive strategies in the event of war designed to place the maximum amount of pressure on the Germans from two directions at once. To sweeten the deal and to improve Russia’s internal lines of communications, the French had invested heavily in Russian railway networks in order to allow the Russians to move supplies to the front much more quickly than had ever been possible before.

The British alliance was, for both sides, much more a matter of convenience. The Anglo-Russian understandings had been designed to eliminate the threat that war might break out between the two powers over the issue of Afghanistan, and with it the western approaches to India. With the threat of war in Central Asia removed, Russia and Britain were free to devote their energies to other pursuits. Russia’s decision to extend its influence east into Manchuria had met with disaster at the hands of the Japanese, making the British alliance all the more important in giving the Russians time to recover.

Nevertheless, although the Russian alliance made good strategic sense for both Britain and France, neither country was totally happy with the association. Both France and Britain were democratic societies with representative governments and active socialist movements. The Russians, by contrast, stood for all of the worst aspects of reaction and repression, offering their subjects virtually none of the freedoms that Frenchmen and Britons had come to take for granted.

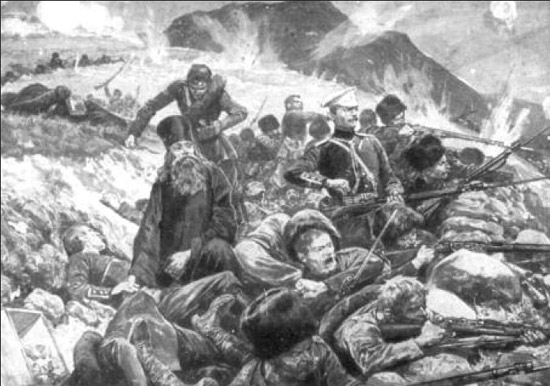

Bulgarian troops during the Balkan Wars. Still reeling from defeat to the Japanese in 1904–05, Russian leaders stayed out of the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. They were determined not to risk irrelevance in the region by staying out of the Balkan Crisis in 1914.

The 7.62mm Russian Mosin-Nagant rifle dated to 1891. Designed by a Russian and manufactured in Belgium, it was an adequate rifle for veterans, but was inaccurate in the hands of inexperienced soldiers. The Mauser rifle used by the Germans was a better weapon.

The left in both countries disliked having their foreign policies tied to that of the Tsar and his regime while the right in both countries tended to remain suspicious of Russian expansionist designs. Especially in Britain, diplomats were very careful not to commit themselves to do too much to help the Russians in the event of a crisis. Nothing in the Anglo-Russian agreements signed in this period bound Britain to go to war for Russia’s sake.

The Franco-Russian agreement, by contrast, did contain measures for collective security. France needed Russia much more than Britain did and as a result had come to live with the distasteful aspects of a Russian alliance. The French had named a beautiful bridge (the Pont Alexandre III, ironically located just a few hundred metres from where Napoleon is entombed) for Nicholas II’s father. In 1896, after Nicholas himself laid the first foundation stone. The flattery of the bridge was part of a much larger series of contacts between the two nations that went far beyond the diplomatic. French investment in Russia increased dramatically and cultural contacts increased as well. In 1909 the Ballets Russes made their first appearance in France to rave reviews. Strategic necessity had indeed made for strange bedfellows.

Assuming the throne in 1894 at the age of 26, Nicholas and his wife firm advocates of the absolutist principle that gave the Tsar the right to rule Russia by the will of God. In 1905 he had to agree to reforms in the face of revolution, but in 1911 he appointed a conservative prime minister who helped him to roll back many of the changes. Insecure and sensitive, he distrusted most of his close advisers and came to rely on the advice of his wife. She proved as insensitive to the suffering of the Russian people as he did, resulting in the slow royal reaction to the misery of the Russian people in wartime.

For the Russians, the alliances with Britain and France helped to secure a diplomatic situation that posed a number of challenges. After 1905 the Russians had largely given up on extending their influence in the East, and had decided to re-engage in the West. They hoped to increase their influence in the Balkans and improve their image significantly among the great powers of Europe. All three of the great Eastern European empires, however, stood in their way.

Their most intractable foe was the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which deeply resented Russian meddling in the Balkans and Russian support for Serbia, whose bellicose leaders dreamed of creating a powerful, pro-Russian pan-Slavic state. Russian interest in the Balkans also unnerved Ottoman Turkey, which had lost two recent wars against Serbia and its Balkan allies.

Nor, despite their diplomatic connections, were the French and British entirely pleased with Russian expansionism. Virtually all Europeans suspected that the ultimate Russian goal was control of the warm water ports in Ottoman Turkey, with Constantinople as the biggest prize of all.

Republican France and autocratic Russia formed an unexpected yet durable alliance. The two powers had agreed to conduct major offensives as quickly as possible in the event of war to keep Germany off balance.

A Russian acquisition of Constantinople represented a much greater leap in Russian power than either France or Britain (to say nothing of Germany and Austria-Hungary) envisioned. After all, the French and British had united just 50 years earlier to fight the Crimean War specifically to prevent such an occurrence. Allies they may have been, but no one in Paris or London wanted to see the Russians gain such a powerful foothold on the eastern Mediterranean. Moreover, most officials in Europe presumed that if Russia did gain Constantinople, it could well lead to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, an event that neither the French nor the British advocated in 1914.

The situation with the Ottoman Empire presented Russia with one of its major foreign policy and military problems. The gradual weakening of the Ottomans had led observers to call it the ‘sick man of Europe’, and most Russians concluded that the collapse of the Ottoman Empire should provide some important opportunities for Russia to fill the power vacuum. Perhaps more importantly, the Russians were loath to see their Austro-Hungarian rivals gain at the Ottomans’ expense instead.

The Ottomans, moreover, presented an unusual problem for the Russians because of their religious and ethnic affinity with the millions of Muslims the Russians had forcibly annexed in the Caucasus region. Russian fears that the Ottomans might issue a call for jihad that would set their southern territories ablaze both gave them cause to seek a more pliable regime in Constantinople and sufficient anxieties about the prospects of war with the Turks.

But Turkey was just one of several fronts the Russians had to defend. From a social and domestic political standpoint the Austro-Hungarian front was the most important. For almost a decade, the Austrians had been locked in a struggle with a resurgent Serbia for influence in the Balkans. This conflict affected Russia through the development of a pan-Slavic ideology used by the Russians to justify their position as a guarantor of freedom to Slavs in southeastern Europe. Focusing on a shared culture and adherence to Orthodox Christianity, the Tsar and his advisers had styled themselves the protectors of the Slavs of the Balkans against either Turkish or Austro-Hungarian pressure.

Austro-Hungarian relations with Serbia grew increasingly shrill and tense. In 1903, a bloody coup in Serbia had violently replaced a generally pro-Austrian regime with an openly pro-Russian one. Three years later, the Austrians responded with a trade embargo against Serbia’s most important export product, thus giving the controversy the name ‘the pig war’. The embargo backfired, as Serbia quickly found new Bulgarian, French, Russian and even German markets for its pork. With the help of Russian financing, overall Serbian exports grew dramatically as a result of the crisis, underscoring the failure of the Austrian policy and boosting Serbian revenue. Frustrated, the Austro-Hungarians annexed the province of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1908 partly to close off that market to the Serbs.

Russia suffered crippling losses in the Russo-Japanese War, forcing a major rearmament effort after the war, much of it funded by France. The Russians hoped to complete their rearmament plan in 1917.

Serbia read the annexation as a threat to their security and a not very cleverly veiled warning from Vienna to fall in line or face a similar fate. The Serbs responded by increasing their calls for the formation of a greater Slavic state in the Balkans that would unite peoples from around the region. As those in Vienna understood all too well, hundreds of thousands of those people lived inside the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Austro-Hungarians therefore heard Serbian calls as a threat to the very unity and sanctity of the empire itself. As tensions between the two states increased, the Serbs naturally called on their Russian ‘protectors’ to put some action into their frequent and extravagant statements of pan-Slavic harmony.

Even without much Russian support, the Slavs themselves handled the Turks through the formation of a Balkan League that humiliated Ottoman armies in the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. As a result of these victories, Serbia doubled in size and more than doubled in confidence and hubris. Still reeling from its debacle in 1904 and 1905, and unwilling to fight the Ottomans over a third-party conflict, the Russians had done little to help the Balkan League in its fight. Some Russians feared that their failure to help the Serbs in the war might undermine their role as Slavic protector, but the Serbian victory left both the Serbs and the Russians in a jubilant mood. Serbia had achieved at least regional power status and, consequently, Russia’s closest Balkan ally had become a real asset. The situation in the Balkans, however, was a tinderbox waiting for a spark.

Ironically, given the blood that flowed between the Germans and the Russians in the twentieth century, many Russians in 1914 saw Germany as the least of their problems. A significant number of ethnic Germans (the so-called Baltic Germans) held key positions in the Russian administrative, professional, business and even military elite. Tsar Nicholas II enjoyed much more cordial relations with his cousin Kaiser Wilhelm II than he did with his other cousin, Britain’s King George V. The Tsar’s wife was known to be openly pro-German and even among many Slavophile Russians there was admiration for the efficiency, wealth and modernization of the Germans. There was also an undeniable similarity in the way both the Russian and German political elites mistrusted and feared the spread of democracy and constitutionalism.

Siberian troops defend Port Arthur against a Japanese assault during the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. One of the features of the war was the extensive use of entrenchments on the battlefield, a fact that was not picked up by the European powers.

But if there was much in common between Russia and Germany, there was much pulling them apart as well. As we will explore below, the Germans did not reciprocate any admiration of Russia. More importantly, the Germans had come to see the Russians as part of the great ‘encirclement’ of Germany along with France and Britain. Thus while the Kaiser and the Tsar might enjoy one another’s company, Wilhelm was angry at Nicholas’s continued alliances with Britain and France. Conflict between the two seemed inevitable, even if much of that conflict owed its origin to problems between the two powers’ allies as much as any problems between the powers themselves.

The Germans, for their part, saw nothing worth admiring in Russia. Much of this attitude came from centuries-old German racism against Slavs. The Germans saw in the Russians, and Slavs more generally, everything that they despised. The Russians were the polar opposites of Germans: unruly, filthy, and backward in almost every sense. They had failed to take advantage of the massive natural resources of the Russian hinterland and had been badly humbled by an Asian power in war, both inexcusable failings in the eyes of early twentieth-century Germans. If anything, the Slavs were seen as impediments to the modernization and development of Eastern Europe and its incorporation into the European system.

German disregard for the Russians had serious consequences. The Germans expected that the Russians would be slow to mobilize and inefficient in their use of their military power. German officers were aware of some of the strengths of the Russians, especially the size of their army and the expanse of their territories, but the Germans were not afraid. They presumed that the natural German advantages of efficiency, leadership and industry would allow them to win a war against a gigantic, but clumsy Russia. Most German senior officers, moreover, believed that an offensive war against Russia was preferable to defensive holding operations because a major offensive would put unbearable strains on the Russian state, as the war against Japan had done in 1904 and 1905.

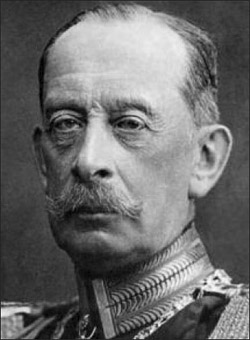

Germany’s Count Alfred von Schlieffen counted on a slow Russian mobilization in designing Germany’s war plans. He expected that the size of Russia and its presumed inefficiency would buy Germany six weeks to defeat France.

In part because the Germans disregarded both the ability and agility of the Russians, German war planners decided to execute an attack on France first. German planners presumed that the Russians would take at least six weeks to mobilize their forces and begin to move west. The now famous Schlieffen Plan thus gambled everything on a lightning strike through Belgium and France that would isolate Paris and force the surrender of the French Government at the end of those six weeks. Then the Germans could move their forces east by train and be ready to defend against any Russian offensive that might materialize. If, as some suspected, the Russians had still not mobilized fully within six weeks, then the Germans could conduct an attack of their own into Russia.

The astonishing confidence of the plan would not have been possible without the equally astonishing manner in which the Germans dismissed the Russians out of hand. Simply put, virtually no one in the German leadership could image a scenario whereby the Russians could mobilize, deploy and fight well enough in the war’s opening weeks and months to influence German strategy and operations in Western Europe. Only a few officers understood enough of the Schlieffen Plan to see how much of a gamble it really was. If even one of its guiding assumptions proved false, then the entire eastern part of Germany would lay dangerously exposed to a Russian advance. East Prussia, the part of Germany most directly in the path of any likely Russian advance, was also home to the estates of many members of the German elite.

The fear and dread of what a Slavic occupation of Germany might mean kept at least one member of that elite awake at night. Paul von Hindenburg had retired from a distinguished German military career to his East Prussian estate. He spent much of his retirement walking around East Prussia examining the possible avenues of approach the Russians might take around the region’s forests and lakes, and then envisioning the most effective German countermeasures. According to one anecdote, he was not entirely happy with what he saw. His wife had asked him his opinion of planting apple trees on the estate and he is supposed to have responded that there was no point, as the only people who would eat the apples would be Russians. Little did he know both that he would soon have the chance to defend East Prussia and that one day, after another war with the Russians, the estate would indeed transfer to a Slavic state, but that it would be Poland, not Russia.

The massive size of the Eastern Front made it virtually impossible for armies to construct the kinds of trench systems that characterized the Western Front. Geographic features like forests, swamps and mountains also played larger roles in the east.

Alfred Redl was an Austrian officer who spied for Russia. His unmasking led to his suicide and a German presumption that the Austro-Hungarian military could not be trusted. As a result the two allies shared very little strategic information, hampering the Central Powers’ war effort.

Hindenburg’s worries were a minority viewpoint. Few other German officials would have delayed planting fruit trees out of fear of the Russians. Oddly enough, most Germans spent more time worrying about their two allies than they did their largest potential enemy. Connections with Austria-Hungary should have been excellent. Military elites in both countries spoke German and both saw Russia as a likely future enemy. The Austro–German alliance was one of the oldest and most solid in Europe, and the two countries shared a long border that opened up many opportunities to develop shared transportation and military infrastructures. Friendly relations allowed each country to save the tremendous expense of fortifying the border. Economic links were also strong, helping to convince the Hungarian part of the empire of the value of closer links to Germany.

Still, trust between the Catholic Austrians and the Protestant Prussians had never run too deep. Most of the senior Austrian officers had forgiven, but not forgotten the Prussian humbling of Austria in the war of 1866. To their eyes, the Germans appeared arrogant and generally condescending. The Germans, for their part, shared Napoleon’s famous view of the Habsburgs as being always one army, one idea and one year too late. The largely agricultural Austro-Hungarian Empire lacked the funds to modernize its army to German expectations and, much to Germany’s chagrin, the Austrians played far too many games in the Balkan backwater rather than focusing on the Russians.

Relations grew even worse when Germany broke off general staff talks with the Austrians in 1911 because of their suspicions that the Russians had a spy in the highest ranks of the Austro-Hungarian Army. They were right. The spy’s name was Alfred Redl, a highly respected intelligence officer who was credited with many innovative techniques. In 1907, Redl had been named head of Austrian intelligence and was one of the highest-ranking officers in the army. He was also homosexual and deeply in debt, two facts that the Russians discovered. They began alternately to bribe and blackmail him into giving them Austro-Hungarian military secrets. German intelligence officials picked up on the betrayal before the Austrians did as a result of an envelope filled with cash that had been sent from Berlin to a post office in Vienna, presumably by Russian agents. The letter, addressed to a pseudonym that Redl used, was returned to Berlin where its contents were discovered and, when combined with the discovery of another letter sent to that address that contained the addresses of spy centres in France and Switzerland, raised the alarm.

Assuming the throne in 1888, the young Kaiser Wilhelm II took control of German affairs by dismissing the legendary Otto von Bismarck in 1890. He possessed a petty jealousy of his English cousins, once calling King Edward VII ‘Satan’. Anxious to improve Germany’s global position, he advocated the construction of an expensive navy and pressed for Germany to challenge the British and French for colonial holdings worldwide. He widely admired the military and revelled in his role as supreme commander of the German armed forces. He understood the military much less than his demeanour suggested, however. His bellicosity played a major role in the increasingly hostile European environment of the pre-war years.

The Germans informed the Austrians of their discovery of a spy. The Austrians staked out the post office hoping to find out the real identity of the man using the pseudonym. Ironically enough, intelligence officers Redl had personally trained found him out and confronted him in May 1913. Under questioning by his own methods, Redl admitted that he had been a spy but it remains unclear if he gave the Austrians much other information of use. His examiners left the room after placing a loaded revolver on the table. They had given Redl the chance to avoid the humiliation of a trial by shooting himself, which he dutifully did. With Redl dead, the Austro-Hungarian political establishment began a cover-up to try to hide the embarrassment of one of their brightest officers having spied for Russia, but the Germans knew that their suspicions had been right all along and that the Austro-Hungarians had had a high-level spy operating in plain view for years without discovery.

The Redl affair emptied whatever credit of faith and trust the Germans had had in their main ally. Although Redl himself was dead, the incident seemed to show that the Germans had been right to suspect the military competence of the Austrians. As a result of this suspicion, the Germans became even less confident of an ally that they felt they could nevertheless not afford to lose. The result of this seeming paradox was an increase in the German arrogance that the Austrians so disliked. Perhaps more importantly, neither side was privy to the war plans of the other. Consequently, neither side understood that no plan existed to deal with the Russians if they should mobilize faster than anticipated.

Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg (left) and Crown Prince Wilhelm (centre), the Kaiser’s son. Both men were deeply steeped in Prussian military traditions and both rose to high ranks during the war itself.

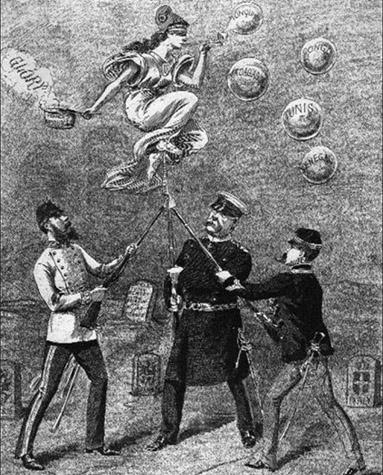

Germany had one other ally, Italy. In 1881 when they joined the Triple Alliance, the Italians were concerned about the expansion of France at a young Italy’s expense and saw a German alliance as protection against such expansion. Over time, however, the French Third Republic showed little interest in territorial expansion in Europe and as a result Franco-Italian relations warmed considerably. Relations between Italy and Austria-Hungary, however, had grown steadily worse. Italian nationalists demanded that Italy annex parts of the Adriatic coastline, including the port city of Fiume, on the ostensible basis that these were historically Italian territories. The Italians also grew shriller in their demands for parts of the Dalmatian coastline and the south Tyrol region in the Alps. To be sure, these regions contained many Italians, but only in parts of the south Tyrol could one plausibly claim that Italian majorities existed. More importantly, all of these territories belonged to Austria-Hungary, placing Italy in the odd diplomatic position of demanding territorial concessions from an ally.

The Kaiser is shown here during a state visit to Turkey. He styled himself the protector of the Muslims in the hopes of undermining the Muslim parts of the British Empire, but found most Muslims unreceptive.

A fanciful image of a united Triple Alliance against France. In reality the three powers had deep mutual suspicions. Neither the Germans nor the Austrians were surprised when Italy left the alliance in 1914. The bubbles each carry the name of a French colony.

Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph had been on the throne since 1848. He had the respect of most of Europe’s leaders, but his age (he was 84 in 1914) made the issue of his successor an important one.

For the Germans, dissension between their two main allies was an unusual, but nevertheless serious problem. Germany felt that it needed both allies and sought to find ways to compromise. German suggestions over the years that the Austrians might cede a few territories with large Italian populations in the interest of alliance harmony only served to infuriate the Austrians further and make them dig their heels in even deeper. Tensions grew so bad by 1914 that Germany had grave doubts (correct, as it turned out) that Italy would honour any of its alliance commitments in the event of war. Those commitments had included sending Italian troops to help defend Alsace and at least a show of force on France’s southeastern border to draw French forces away from the German front. Losing Italy meant not just losing the threat to France, but the sizeable Italian fleet in the Mediterranean as a way to interdict British and French commerce.

Dissatisfaction with both Italy and Austria-Hungary helps to explain German fascination with an alliance with the Ottoman Empire. Both nations shared an historical mistrust of the Russians and the Kaiser hoped to use the Ottoman Empire’s religious authority to undermine British control of Muslim India. The Kaiser had even made an appearance in Constantinople in a fez proclaiming Germany the protector of the world’s Muslims, a statement that mystified and confused most who heard it. As a more believable sign of his desire for growing contacts, the Kaiser had sent a high-level military mission to Turkey to help modernize the Ottoman Army and its coastal defences, and had also vastly increased German investments in Turkey, especially in supporting the construction of the so-called Berlin to Baghdad railway.

As tensions rose in the weeks leading up to war, the Germans staked more and more on the Ottoman connection. Just days before the onset of fighting a stroke of good fortune helped them. As war between Britain and Germany loomed, the British cancelled shipment of two recently completed modern battleships to the Turkish Navy on the grounds of national security. The ships had been paid for in part by public subscription, and most Turks saw the cancellation as a slap in the face. The Germans had two battleships in the Mediterranean at the time and they knew that the British would never let those ships get back to German waters. Therefore, at almost the same time that war was declared in Europe, the Germans made the smart decision to transfer the two ships to Ottoman control, knowing that the British would not fire on a ship from a still neutral nation. The two ships would thus be saved and would cement the links to Turkey by making good the British insult to Turkish pride. After daringly avoiding the British ships sent to track them, the Goeben and the Breslau arrived in Constantinople on 10 August where they entered the Turkish Navy as the Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Midili. The German commander of the ships, the most powerful vessels in the Ottoman fleet, was soon named commander-in-chief of the Ottoman Navy. By then the Germans and the Ottomans had already signed an alliance and the Italians had announced their intention to remain neutral.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand put more than succession to the Austro-Hungarian throne in doubt. It threatened the peace of the Continent when German and Austro-Hungarian leaders decided to use it as a pretext for a Europe-wide war.

Austria-Hungary’s position was in many ways the most complicated of the Eastern European powers. A multi-ethnic empire dominated by Germans and Magyars (Hungarians), the empire was itself a defiance to the logic of nationalism that had been so forceful in carving out modern Europe. The empire contained members of almost all of Eastern Europe’s minorities, along with the all the complexities that such a mix of languages, cultures and religions implied. The empire tried to hold this conglomeration together through a generally high level of official tolerance (Austria-Hungary, for example, had the Continent’s only Jewish generals) and shared allegiance to the central institutions of the empire, the monarchy and the army. Both of those institutions, however, were too closely identified with the German elite to be seen as representative.

Ever since its collapse, the weaknesses of the Austro-Hungarian state have become its most dominant features among historians. This picture is not far from the truth. Based on the outdated principle of multi-ethnic nationalities, it was seen by many at the time as being ‘on the wrong side of history’. The emperor, the ageing Franz Joseph, had been on the throne since 1848, making him the oldest monarch in Europe. He neither inspired much confidence nor proved particularly well adapted to meet the changes of the twentieth century. Economically, the country was largely agricultural, although it did possess several important industrial centres. Politically, the empire worked through an one based in Vienna and one in Budapest, which worked with different systems and different languages.

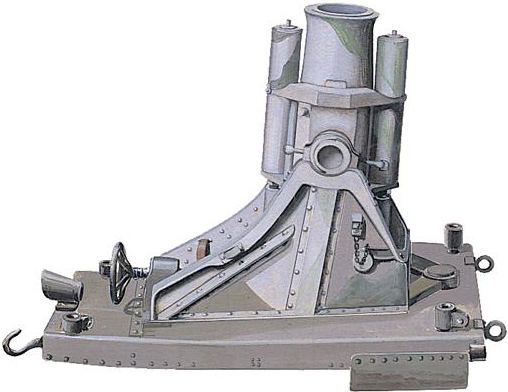

Nevertheless, the empire was counted by all of its contemporaries as a great power, even if it was one on the decline. It controlled a massive amount of territory, much of it strategically placed, and if its bureaucracy was cumbersome, it still managed to function most of the time. The empire also had a large population and an officer corps that thought itself the inheritors of a proud tradition worth defending. Although Austria-Hungary was not a wealthy state, the army was able to get from it most of what it wanted and, in several areas, it was highly respected. Even the Germans sought out the excellent artillery pieces that emerged from the Skoda Works.

Although the Austro-Hungarian military was deficient in many respects, it possessed excellent artillery pieces from the Skoda Iron Works in Bohemia. The guns were so good that even the industrially advanced Germans ordered them for their military.

‘It will be a hopeless struggle, but nevertheless it must be, for such an ancient monarchy and such an ancient army cannot perish ingloriously.’

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf

Despite outward manifestations of confidence, a deep sense of anxiety pervaded Austria-Hungary’s leadership. The state’s elite felt that it had no dependable allies and a host of potential enemies. In fact, one of its allies (Italy) was also one of its most likely future enemies. The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 seemed to make clear what Austria-Hungary ought to do next. Most members of the state’s elite wanted to fight a punitive war against the Serbian state that it held directly responsible for the assassination. Such a war would also eliminate the Serbian threat once and for all and leave Austria-Hungary as the dominant force in the Balkans.

The chief of the Austro-Hungarian general staff, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, had been arguing for such a war for years. Known in Austrian circles as a hothead who repeatedly argued for pre-emptive wars both in the Balkans and against Italy, Conrad saw several other important advantages in a war with Serbia. The victory that he fully expected would result would reverse the empires’s decline and confirm Austria-Hungary’s placement among the ranks of the great powers. Conrad believed strongly that the government had made an unforgivable mistake by not striking the Serbs while they were occupied with their war against the Ottoman Empire in 1912. Now with the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne and his wife dead at the hands of a Serbian terrorist group with ties to the government, the time had come, he believed, to right the wrong and deal with Serbia in the most violent manner possible. The assassination had given him the perfect opportunity to fight an offensive war while at the same time playing the international role of victim.

Conrad von Hötzendorf (right) had been arguing for war against Serbia for years. As chief of the Austrian general staff, he seized upon the assassination of Franz Ferdinand as a proper and useful justification for war. He wished to return Austro-Hungary to its former status as a leading great power.

The problem, Conrad knew, was that war with Serbia might also mean war with Russia. That problem, he hoped, had been solved by the German ‘blank cheque’ offer of support. German officials had decided that the assassination of a member of the royal family had to be answered and therefore that Austria-Hungary would be entirely within its rights to invade Serbia.

The Germans had also concluded that the Russians would in all likelihood enter the war as a result. Having noted the massive improvements and investments the Russians and French were making to their militaries, the Germans determined that the odds were more in their favour in 1914 than they were likely to be in the future. They therefore told their ally to do what was necessary against Serbia and count on full German support to deal with the consequences.

What Conrad failed to realize, however, was that German mobilization for war meant that Germany would execute and implement a war plan that sent seven-eighths of its forces against France in the west. There they would be of little help to the Austro-Hungarian forces that would mostly head south to crush Serbia. As a result of the failure to coordinate their war plans, the two powers had inadvertently left themselves with grossly inadequate coverage against the Russians. Even before this amazing oversight was understood, Conrad knew that the Austro-Hungarian Empire, with its many weaknesses, was headed into a dangerous future. ‘It will be a hopeless struggle,’ he wrote just before the fighting began, ‘but nevertheless it must be, for such an ancient monarchy and such an ancient army cannot perish ingloriously.’ Ingloriously or not, the Austro-Hungarians were indeed on their way to perishing.