Nine

Stuff in the Air (and Elsewhere)

May we recommend

‘Rectal Impalement by Pirate Ship: A Case Report’

by M. Bemelman and E.R. Hammacher (published in Injury Extra, 2005)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Greetings with potent bugs • Mighty (Marm- and Vege-) mites for mighty few nations • Mozart killer notions • Sudden late pacemaker boom • Too-close look at a pipe • A surprise for the self-auto-shocked snakebit marine • Dragonflies on a black gravestone • U for the ducks • Pop-up pop-off procedure, for bears • The further adventures of Troy Hurtubise • Upside-down sunken-dinosaur scheme • Approaches to parachuting • Insurance for clowns • The tragedy of pizza delivery • Cadaverine and putrescine up your nose • Crimefighting with dolls • Brain extraction on the quick • Dead mules in a literary niche

A handy guide to pathogens

How many pathogens per handshake? Is it dangerous to shake hands at a school graduation?

Dr David Bishai and a team at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, did a small experiment. They wanted to gauge whether the people most at peril should worry about it.

Their report, ‘Quantifying School Officials’ Exposure to Bacterial Pathogens at Graduation Ceremonies Using Repeated Observational Measures’, was published in the Journal of School Nursing. ‘This study was designed to measure the degree to which principals and deans are potentially exposed to the risk of pathogen acquisition as part of their occupational duties to shake hands.’

The write-up has some small human touches.

The team recruited officials who had leading roles in graduation ceremonies at elementary, secondary and post-secondary schools in the state of Maryland. Fourteen authority figures agreed to be the subjects of the experiment. Beforehand, each of the fourteen washed with an alcohol-based sanitizer. Then, and afterwards when all the handshaking was done, ‘each of the participant’s hands was set on a clean drape and swabbed from the base of the thumb to the side of index finger and then around the edges of the other fingers to account for all possible areas for hand contamination during a handshake’.

The risk is pretty small, the results imply. Only two of the fourteen school officials had pathogenic bacteria on hand post-graduation – and only one of those was on the right, shaking hand. Twirling the numbers for perspective, the study explains there is a ‘0.019% probability of acquiring a pathogen per handshake’.

The researchers point out many reasons why their study is just a preliminary, quick sketch of the story. They examined only a few school officials, and tested for only two kinds of pathogens. Medical science is not clear yet on the prevalence of those pathogens on people’s hands in general. Nor is it clear that the microbes’ mere presence on the outside (rather than inside) of the body is indicative of danger.

And school graduations are just a sliver of the human experience: ‘Graduates may have a different level of infectiousness from other members of the community with whom one might shake hands, making our results less useful to politicians, business executives and clergy.’

Bishai, David, Liang Liu, Stephanie Shiau, Harrison Wang, Cindy Tsai, Margaret Liao, Shivaani Prakash and Tracy Howard (2011). ‘Quantifying School Officials’ Exposure to Bacterial Pathogens at Graduation Ceremonies Using Repeated Observational Measures’. Journal of School Nursing 27 (3): 219–24.

More than just a condiment

Marmite, the born-in-Britain foodstuff with a powerful taste and a whiff-of-superhero-comic-book name, is more than just a condiment. Marmite, together with its younger, Australian-borne kinsman Vegemite, is an ongoing biomedical experiment.

Streaky dabs of information appear here and there, spread thin, on the pages of medical journals dating back as far as 1931.

The 1930s were a sort of golden period for Marmite. A steady diet of Marmite reports oozed deliciously from several medical journals. Likely many physicians ingested them whilst munching Marmite on toast.

Dr Alexander Goodall of the Royal Informary of Edinburgh regaled readers of The Lancet with a case report called ‘The Treatment of Pernicious Anæmia by Marmite’. Goodall told how a British Medical Journal article, published the previous year, had inspired him and benefited his patients: ‘The publication by Lucy Wills of a series of cases of “pernicious anaemia of pregnancy” and “tropical anaemia” successfully treated by marmite raises many questions of importance … Since the publication of Wills’s paper I have treated all my “maintenance” cases with marmite. Without exception these have done well.’

Two weeks later, also in The Lancet, Stanley Davidson of the University of Aberdeen disagreed. ‘It would be very unwise at the present stage’, he wrote, ‘to suggest that marmite can replace liver and hog’s stomach preparations’.

Lancet readers also got to learn about ‘Marmite in Sprue’, ‘The Treatment by Marmite of Megalocytic Hyperchromic Anaemia: Occurring in Idiopathic Steatorrhœa’, and ‘The Nature of the Hæmopoietic Factor in Marmite’.

Vegemite starred quietly in a 1948 monograph in the Journal of Experimental Biology entitled ‘Studies in the Respiration of Paramecium caudatum’. Beverley Humphrey and George Humphrey of the University of Sydney described how they grew and nurtured their microbes: ‘The culture medium consisted of 5 milliliters of Osterhout solution and 5 milliliters of 20% Vegemite suspension in 1 liter of distilled water. The Vegemite is a yeast concentrate manufactured by the Kraft-Walker Cheese Co. Pty. Ltd., Australia, and served to support a rich bacterial flora upon which the Protozoa fed.’ Humphrey and Humphrey’s Vegemite adventure contributed, they said, to ‘the slow advance of our knowledge of the nutrition of most types of Protozoa’.

A 2003 paper called ‘Vegemite as a Marker of National Identity’, published in the journal Gastronomica, contributed to the slow advance of knowledge of native Australians’ liking for the food stuff. Paul Rozin and Michael Siegal surveyed a few hundred students at the University of Queensland, yielding up a table of numbers contrasting their relative (and in many cases relatively large) enjoyment of that substance in comparison with coffee and other common foods. The numbers indicate that Vegemite and carrots enjoyed about equal favour, not as high as chocolate but towering far above sardines or Marmite.

Table 1 from ‘Vegemite as a Marker of National Identity’

In a very few cases, researchers thought they could see hints of a darker side to Vegemite and Marmite.

A 1985 report called ‘Vegemite Allergy?’, published in the Medical Journal of Australia, told of a fifteen-year old girl with asthma: ‘She has noted over the last 2–3 years that ingestion of Vegemite, white wine or beer seems to induce wheezing within a short period of time.’ The doctors concluded that hers was a ‘suspicious theory’.

Four years later, Dr Nigel Higson of Hove issued a bitter warning in the British Medical Journal under the headline ‘An Allergy to Marmite?’. Higson wrote: ‘Some health visitors advise mothers to put Marmite on their nipples to break the child’s breast feeding habit; in a susceptible child this action might possibly be fatal.’

Goodall, Alexander (1932). ‘The Treatment of Pernicious Aaemia by Marmite’. The Lancet 220 (5693): 781–2.

Wills, Lucy (1931). ‘Treatment of “Pernicious Anaemia of Pregnancy” and “Tropical Anaemia” with Special Reference to Yeast Extract as a Curative Agent’. British Medical Journal i: 1059–64.

Wills, Lucy (1933). ‘The Nature of the Haemopoietic Factor in Marmite’. Lancet 1: 1283–6

Davidson, Stanley (1932). ‘Marmite in Pernicious Anaemia’. The Lancet 220 (5695): 919–20.

Rogers, Leonard (1932). ‘Marmite in Sprue’. The Lancet 219 (5669): 906.

Vaughan, Janet M., and Donald Hunter (1932). ‘The Treatment by Marmite of Megalocytic Hyperchromic Anæmia: Occurring in Idiopathic Steatorrhoea (Coeliac Disease)’. The Lancet 219 (5668): 829–34.

Humphrey, Beverley A., and George F. Humphrey (1948). ‘Studies in the Respiration of Paramecium caudatum’. Journal of Experimental Biology 25 (June): 123–34.

Rozin, Paul, and Michael Siegal (2003). ‘Vegemite as a Marker of National Identity’. Gastronomica 3 (4): 63–7.

van Asperen, P.P., and A. Chong (1985). ‘Vegemite Allergy?’. Medical Journal of Australia 142 (3): 236.

Higson, Nigel (1989). ‘An Allergy to Marmite?’. British Medical Journal 298 (6667): 190.

Mozart’s dark death

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart has died a hundred deaths, more or less. Here’s a new one: darkness.

Doctors over the years have resurrected the story of Mozart’s death again and again, each time proposing some alternative horrifying medical reason why the eighteenth century’s most celebrated and prolific composer keeled over at age thirty-five. One monograph suggests that Mozart died from too little sunlight.

The researchers give us a simple theory. When exposed to sunlight, people’s skin naturally produces vitamin D. Mozart, towards the end of his life, was nearly as nocturnal as a vampire, so his skin probably produced very little of the vitamin. (The man failed to take any vitamin D supplements to counteract that deficiency. But that wasn’t Mozart’s fault. Only much later, in the 1920s, did scientists identify a clear link between vitamin D, sunlight and good health. Vitamin D supplements did not go on sale in Salzburg and Vienna, Mozart’s home towns, until many years after that.)

Stefan Pilz (who, if he plays his cards right, will hereafter be known as ‘Vitamin’ Pilz) and William B. Grant published their report, called ‘Vitamin D Deficiency Contributed to Mozart’s Death’, in the journal Medical Problems of Performing Artists. Pilz is a physician/researcher at the Medical University of Graz, Austria. Grant is a California physicist whose background is in optical and laser remote sensing of the atmosphere, and atmospheric sciences.

Pilz and Grant explain: ‘Mozart did much of his composing at night, so would have slept during much of the day. At the latitude of Vienna, 48º N, it is impossible to make vitamin D from solar ultraviolet-B irradiance for about six months of the year. Mozart died on 5 December 1791, two to three months into the vitamin D winter.’

They acknowledge the existence of competing medical theories. They do not bother mentioning the possibility, depicted in Peter Shaffer’s 1969 play Amadeus, that a rival composer did him in. Other academic studies do examine the evidence for poisoning; most conclude that that evidence is lame.

Rival doctors and historians have presented arguments, in medical and other academic journals, that Mozart perished from acute rheumatic fever, bacterial endocarditis, streptococcal septicemia, tuberculosis, cardiovascular disease, brain haemorrhage, hypertensive encephalopathy, congestive heart failure, uremia secondary to chronic kidney disease, pyelonephritis, congenital urinary tract anomaly with obstructive uropathy, bronchopneumonia, haemorrhagic shock, post-streptococcal Henoch-Schönlein purpura, polyarthritis, trichinellosis, amyloidosis and quite a few other unpleasantnesses.

Other studies have tried to tease out biomedical causes for some of Mozart’s eccentric behaviour. Two of the more abstruse are by Benjamin Simkin. In 1999 he wrote about a concept called ‘Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal infection’ (PANDAS). The study is called ‘Was PANDAS Associated with Mozart’s Personality Idiosyncrasies?’. It expanded on Simkin’s curse-filled 1992 monograph in the British Medical Journal called ‘Mozart’s Scatological Disorder’.

From ‘Mozart’s Scatological Disorder’ (1992). The author goes on to inventory the scatological terms in Mozart’s letters, including ‘arse’, ‘muck’, ‘piddle or piss’ and ‘fart’.

Grant, William B., and Stefan Pilz (2011). ‘Vitamin D Deficiency Contributed to Mozart’s Death’. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 26 (2): 117.

Dawson, William J. (2010). ‘Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart – Controversies Regarding His Illnesses and Death: A Bibliographic Review’. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 25 (2): 49.

Zegers, Richard H.C., Andreas Weigl and Andrew Steptoe (2009). ‘The Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: An Epidemiologic Perspective’. Annals of Internal Medicine 151 (4): 274–8.

Simkin, Benjamin (1999). ‘Was PANDAS Associated with Mozart’s Personality Idiosyncrasies?’. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 14 (3): 113.

— (1992). ‘Mozart’s Scatological Disorder’. British Medical Journal 305 (19 Dec): 1563.

Research spotlight

‘Sunshine and Suicide Incidence’

by Martin Voracek and Maryanne L. Fisher (published in Epidemiology, 2002)

‘Solar Eclipse and Suicide’

by Martin Voracek, Maryanne L. Fisher and Gernot Sonneck (published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, 2002)

The problem of exploding pacemakers

People muse that they will, come the day, ‘go out with a bang’. A little more often than you might expect, someone or other does exactly that, which is why there came into existence a study called ‘Pacemaker Explosions in Crematoria: Problems and Possible Solutions’. Christopher Gale, of St James’s University Hospital in Leeds, and Graham Mulley, of the General Infirmary at Leeds, published the report in 2002 in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine.

The first crematorium pacemaker explosion on record happened in 1976 in Solihull, in the West Midlands. As pacemakers and cremations both became popular, Gale and Mulley explain, after-death explosions came to be expected.

Table 1, showing responses from 188 crematoria staff who responded to the questionnaire.

In the wake of the Solihull surprise, the British Medical Journal published an essay entitled ‘Hidden Hazards of Cremation’. It speaks of the incident, and speculates about even worse things. There are individuals, it points out, who, as a result of medical procedures, contain tiny amounts of radioactive substances: yttrium-90, iodine-131, gold-198, phosphorus-32 and their ilk. ‘There is a possibility’, the anonymous author confides, ‘that an explosion (or some other event) during the cremation of a radioactive corpse could produce a blow-back releasing radioactive smoke or fumes into the crematorium. This risk seems to be largely theoretical, but …’

Soon, two questions were added to Form B of the government-mandated Cremation Act Certificate, which a physician fills out prior to a cremation. ‘Has a pacemaker or any radioactive material been inserted in the deceased (yes or no)?; (b) If so, has it been removed (yes or no)?’ (Form B, after being retooled, eventually came to the end of its own life, and was replaced in 2008.)

Gale and Mulley surveyed the managers of all 241 cremation facilities in the UK, asking: ‘(1) Have you ever had personal experience of pacemaker explosions in crematoria? (2) What do you estimate is the frequency of pacemaker explosions in crematoria?’ About half the respondents admitted to ‘personal experience’ of pacemaker explosions. Gale and Mulley suspected that the actual numbers were more dire. ‘Staff may not wish to mention these events’, they write, ‘and their recall may not be accurate.’ Gale and Mulley also concluded that ‘crematoria staff rely on accurate and complete cremation forms’ – but that the information-gathering/reporting process could, and often did, go astray.

The pair published another report, two years later, to show that pacemakers themselves sometimes go astray. Called ‘A Migrating Pacemaker’, it tells how Dr Gale failed, using his medically trained hands and fingers, to find the pacemaker in a seventy-nine-year-old deceased man. The man’s medical records said there should be one.

Gale got a hand-held metal detector, which showed that the pacemaker had moved elsewhere in the body. He concluded that medical devices don’t always stay exactly where surgeons originally placed them, and he recommends using hand-held metal detectors to ‘help prevent explosions in crematoria’.

Gale, Christopher P., and Graham P. Mulley (2002). ‘Pacemaker Explosions in Crematoria: Problems and Possible Solutions’. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 95 (7): 353–5.

— (2005). ‘A Migrating Pacemaker’. Postgraduate Medical Journal 81: 198–9.

n.a. (1977). ‘Hidden Hazards of Cremation’. British Medical Journal 2 (24 Dec): 1620–1.

In brief

‘Airbag Deployment and Eye Perforation by a Tobacco Pipe’

by F.H. Walz, M. Mackay and B. Gloor (published in the Journal of Trauma, 1995)

The rattling tale of Patient X

The self-inflicted snake/electroshock saga of Patient X turned out, twenty-one years after it entered the public record, to have an earlier chapter that had not made it into print.

That’s Patient X, the former US marine who suffered a bite from his pet rattlesnake. Patient X, the man who immediately after the bite insisted that a neighbour attach car spark plug wires to his lip, and that the neighbour rev up the car engine to 3,000 rpm, repeatedly, for about five minutes. Patient X, the bloated, blackened, corpse-like individual, who subsequently was helicoptered to a hospital where Dr Richard C. Dart and Dr Richard A. Gustafson saved his life and took photographs of him.

Patient X, who featured in the treatise called ‘Failure of Electric Shock Treatment for Rattlesnake Envenomation’, which Dart and Gustafson published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine in 1991, in consequence of which the three men shared the Ig Nobel Prize in medicine in 1994.

Though rattlesnake bites can be deadly, there is a standard, reliable treatment – injection with a substance called ‘antivenin’. Patient X preferred an alternative treatment. The medical report explains: ‘Based on their understanding of an article in an outdoorsman’s magazine, the patient and his neighbour had previously established a plan to use electric shock treatment if either was envenomated.’

One day while Patient X was playing with his snake, the serpent embedded its fangs into Patient X’s upper lip. The neighbour sprang into action. As per their agreement, he laid Patient X on the ground next to the car, and affixed a spark plug wire to the stricken fellow’s lip with a small metal clip. The rest you know, at least in outline.

Gustafson eventually went to work for a US Defense Department official agency involved in ‘countering weapons of mass destruction’. In 2012 he told me about a conversation he had with Patient X, but did not mention in the medical report: ‘I started off by telling Patient X, who was a US marine, that I had been an active duty Navy corpsman. Therefore, I was asking Patient X about his medical history and got around to asking him if he had ever been envenomed by a snake before and if so what treatment did he receive. He said that he had been “bitten” a couple years ago on Okinawa. I then asked him if it had been a Habu, a type of cobra common to Okinawa, and he said yes. I then asked if he had been bitten on his middle finger of his left hand, up in the northern training area, and helicoptered down to Lester Naval hospital to the ER [emergency room]. He said hesitantly “yes”. I then informed Patient X that I was the corpsman who was assigned to his care, to monitor his condition for the six hours he was in the ER, prior to being admitted to the hospital as an in-patient.’

Dart, Richard, and Richard Gustafson (1991). ‘Failure of Electric Shock Treatment for Rattlesnake Envenomation’. Annals of Emergency Medicine 20 (6): 659–61.

Research spotlight

‘The RaTio of 2nd to 4th Digit Length: A New Predictor of Disease Predisposition?’

by John T. Manning and Peter E. Bundred (published in Medical Hypotheses, 2000)

Professor Manning hypothesizes: ‘The ratio between the length of the 2nd and 4th digits is: (a) fixed in utero; (b) lower in men than in women; (c) negatively related to testosterone and sperm counts; and (d) positively related to oestrogen concentrations. Prenatal levels of testosterone and oestrogen have been implicated in infertility, autism, dyslexia, migraine, stammering, immune dysfunction, myocardial infarction and breast cancer. We suggest that 2D:4D ratio is predictive of these diseases.’

Signalling a grave attraction

Gábor Horváth, head of the Environmental Optics Laboratory at Eotvos University in Budapest, Hungary, solves mysteries about light and about living creatures. Among these, he discovered that white horses attract fewer flies. He and five colleagues wrote a study called ‘An Unexpected Advantage of Whiteness in Horses: The Most Horsefly-proof Horse Has a Depolarizing White Coat’, which they published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers experimented with a small number of sticky horses and a large number of horseflies (of the variety called tabanids). The horses were sticky because the scientists had coated them with ‘a transparent, odourless and colourless insect monitoring glue [called] Babolna Bio mouse trap’.

The scientists brought those horses – one black, one brown, one white – to a grassy field in the town of Szokolya, Hungary. Every other day, they collected and counted the flies that had become attached to the sticky horses.

The results, tallied over fifty-four summer days: the sticky brown horse Babolna-Bio-mouse-trapped fifteen times as many flies as the sticky white horse. And the black horse, poor thing, trapped a whopping, buzzing twenty-five times as many flies as the white one.

The differences, say the scientists, come from the way light bounces off horsehair. Polarized light – light that’s all vibrating in the same direction – attracts horseflies. When that light reflects off dark fur, it stays polarized. But when polarized light glances off white fur, it becomes less polarized, which, to a horsefly, is not so attractive.

At the very end of the report, Horváth alludes coquettishly to another of his experiments, one he has not yet written up. It’s a case of animal and animal on animal: ‘When white cattle egrets, for example, are sitting on the back of dark-coated cattle and pecking blood-sucking tabanids away from the cattle, tabanids blending in colour with that of their hosts’ fur might derive greater protection owing to camouflage.’

Indeed, Gábor Horváth has tackled other colourful questions. He and several collaborators reported that red cars attract insects. Details are in the report ‘Why Do Red and Dark-coloured Cars Lure Aquatic Insects?: The Attraction of Water Insects to Car Paintwork Explained by Reflection-polarization Signals’, also published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Horváth’s team likewise discovered that black gravestones attract dragonflies. Read about that in a paper called ‘Ecological Traps for Dragonflies in a Cemetery: The Attraction of Sympetrum species (Odonata: Libellulidae) by Horizontally Polarizing Black Grave-stones’, published in the journal Freshwater Biology.

Not all Gábor Horváths are equally colourful in their scientific writings. Across town, at Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BUTE), associate professor of electrical engineering Gábor Horváth can boast an impressive array of published research work. But to non-specialists most of it looks comparatively unspectacular – the one slight exception being his monograph entitled ‘A Sparse Robust Model for a Linz-Donawitz Steel Converter’.

Horváth, Gábor, Miklós Blahó, György Kriska, Ramón Hegedüs, Baláz Gerics, Róbert Farkas and Susanne Åkesson (2010). ‘An Unexpected Advantage of Whiteness in Horses: The Most Horsefly-proof Horse Has a Depolarizing White Coat’. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277 (1688): 1643–50.

Kriska, György, Zoltán Csabai, Pál Boda, Péter Malik and Gábor Horváth (2006). ‘Why Do Red and Dark-coloured Cars Lure Aquatic Insects?: The Attraction of Water Insects to Car Paintwork Explained by Reflection-polarization Signals’. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 273 (1594): 1667–71.

Horváth, Gábor, Péter Malik, György Kriska and Hansruedi Wildermuth (2007). ‘Ecological Traps for Dragonflies in a Cemetery: The Attraction of Sympetrum species (Odonata: Libellulidae) by Horizontally Polarizing Black Grave-stones’. Freshwater Biology 52 (9): 1700–9.

Valyon, József, and Gábor Horváth (2008). ‘A Sparse Robust Model for a Linz-Donawitz Steel Converter’. IEEE Transacations on Instrumentation and Measurement 58 (8): 2611–7.

Uranium is for the birds

Depleted uranium should, perhaps, be the ammunition of choice for duck hunters. That’s the conclusion of a study called ‘Response of American Black Ducks to Dietary Uranium: A Proposed Substitute for Lead Shot’.

Published in 1983 in the Journal of Wildlife Management, the recommendation has not been much disputed. The study’s authors, biologists Susan Haseltine and Louis Sileo, were based at the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center in Laurel, Maryland.

Lead shot is dangerous for ducks, especially if it hits them. When it doesn’t hit a duck (or hit another hunter, as sometimes happens), the shot falls into the wetlands. The lead leaches into the muck, slowly poisoning whichever ducks have managed to avoid being shot.

In many hunting areas, lead shot is verboten. At the time of the study, steel was being touted as the best alternative to lead. But Haseltine and Sileo pointed out its drawbacks. They wrote that ‘Steel shot shells are more expensive than lead shot shells when purchased in a retail outlet; they cannot be used in all guns and have not been well received by some hunters who question their performance on ducks and geese.’

Haseltine and Sileo credit the idea – substituting uranium for steel – to metallurgist Carl A. Zapffe of Baltimore. Zapffe was no slouch about steel; witness his 1948 study: ‘Evaluation of Pickling Inhibitors from the Standpoint of Hydrogen Embrittlement: Acid Pickling of Stainless Steel’. Zapffe also wrote a book disputing Einstein’s theory of special relativity, but that is a separate matter.

Haseltine and Sileo listed what they call the ‘attractive characteristics’ of depleted uranium as a raw material for making birdshot. ‘In its pure form’, they wrote, ‘it is denser than lead and, in alloys, might be made to produce shot patterns and velocities attractive to hunters and within the effective range for waterfowl. Depleted uranium can be alloyed with many other metals and its softness and corrosiveness can be altered over a wide range.’

But nothing is perfect. ‘Negative aspects for potential uranium shot include pyrophoricity [proneness to spontaneously burst into flames] problems with pure depleted uranium, which can be altered by alloying, and the expense of separating depleted uranium from other nuclear waste products.’

Their main argument was that uranium may not be very poisonous even to a duck that, of its own accord, swallows some in pellet form. That is what Haseltine and Sileo sought to verify.

They fed forty ducks a diet of commercial duck mash salted with powdered depleted uranium. None of the ducks died of it, or got sick, or even lost weight. Moreover, the researchers reported, the ducks ‘were in fair to excellent flesh’ when slaughtered. And so they enthused that ‘further examination of this metal as a substitute for lead in shot is justified.’ However, no one has yet followed up on this in a big way for hunting anything other than people.

Haseltine, Susan D., and Louis Sileo (1983). ‘Response of American Black Ducks to Dietary Uranium: A Proposed Substitute for Lead Shot’. Journal of Wildlife Management 47 (4): 1124–9.

Zapffe, Carl A., and M. Eleanor Haslem (1948). ‘Evaluation of Pickling Inhibitors from the Standpoint of Hydrogen Embrittlement: Acid Pickling of Stainless Steel’, Wire and Wire Products 23 (10): 933–9.

Ricker III, Harry H. (2006). ‘Dr. Carl Andrew Zapffe: A “Cod” Proposes a “Flying Interferometer”’. General Science Journal, 15 November, http://www.gsjournal.net/old/science/ricker24.pdf.

— (2007). ‘An Introduction to Dr. Carl A. Zapffe’s Classic Paper: A Reminder on E=mc2’. General Science Journal, 3 March, http://gsjournal.net/Science-Journals/Research%20Papers-Relativity%20Theory/Download/866.

Zapffe, Carl A. (1982). A Reminder on E=mc2, m=mo(1-v2/c2)-1/2, & N=Noe-t’/gt. n.a.: privately published.

—. (1985). ‘Exodus of Einstein’s Special Theory in Seven Simple Steps’. The Toth-Maatian Review 3 (4): 1531–5.

May we recommend

‘Carbon Monoxide: To Boldly Go Where NO Has Gone Before’

by Stefan W. Ryter, Danielle Morse and Augustine M.K. Choi (published in Science STKE, 2004)

A bear to cross

When a big bear approaches, some people choose to quietly stroll away. To give them an extra measure of safety, Anthony Victor Saunders and Adam Warwick Bell invented what they call a ‘Pop-up Device for Deterring an Attacking Animal such as a Bear’.

Saunders, a London-based mountain climber, and Bell, a California patent attorney, applied for a patent in 2003, but later abandoned it. They would equip hikers with, essentially, an inflatable doll ‘meant to scare away an attacking or aggressive animal such as a bear’. The frightful balloon could also be used against ‘elk, moose, mountain lions, buffalo, hippopotamus, rhino, elephant, boar’. They explain that it ‘works on the principle of maximizing the apparent size and ferocity of the human, intimidating the bear’.

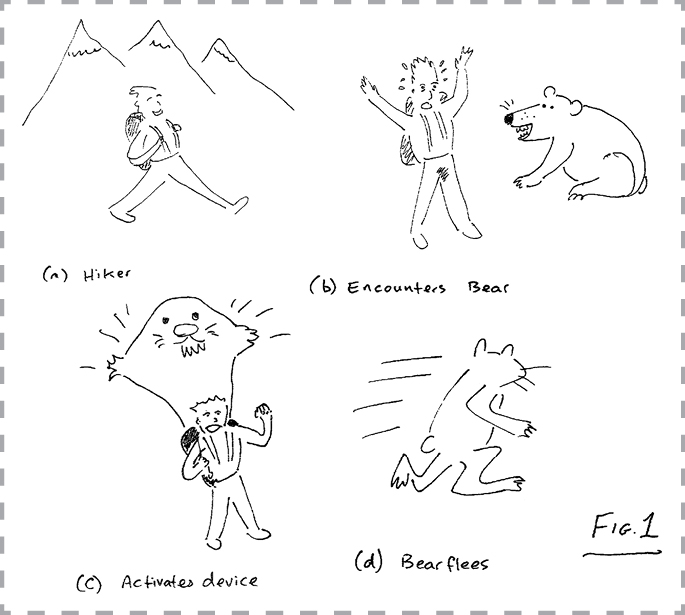

Events leading to the use of the pop-up device

In the patent application, Saunders and Bell refined their thoughts. Here’s how they decided the device must deploy quickly: ‘The figure should be fully inflated within less than one minute, or within less than 30 seconds, or preferably within less than 10 seconds, or most preferably five seconds.’ The device can be ‘incorporated into clothing or luggage [or] into the hilt of a walking-stick’ and activated ‘by pulling a cord. The figure would inflate and pop up out of the back-pack, presenting the attacking bear with a huge and frightening opponent’.

The bear then gets an escalating series of surprises, beginning with ‘one or more explosive “bangs”, a fog-horn, or a loud roaring or screaming sound’. The noise is augmented with smells. ‘The musky odour of a bear helps convince the attacking bear that he is being faced with a powerful, aggressive and musky opponent.’ Then would come ‘an odorous or noxious gas or liquid’.

There’s also smoke: ‘from a typical “smoke-bomb” type of device’.

Some bears are not easily deterred. So ‘the deployment of the device may be accompanied by the launching of projectiles. [This] would further confuse, scare and disorientate the bear. Such projectiles could be launched from a mortar or mortar-type device’.

The whole thing, they say, is ‘detachable and may be left between human and bear as the human retreats’.

Inventors Saunders and Bell are not the only pioneering individuals to consider novel methods for greeting bears. In this era of ‘big science’, there are still people who pursue thoughtful, original research, unencumbered by official scientific credentials, academic bureaucracies or government funding. Troy Hurtubise is a fine example of the breed.

At age twenty, out alone panning for gold in the Canadian wilderness, Hurtubise had an encounter of some sort with a grizzly bear. He has devoted the rest of his life to creating a grizzly-bear-proof suit of armour in which he could safely go and commune with that bear. The suit’s basic design was influenced by the powerful humanoid-policeman-robot-from-the-future title character in Robocop, a film Hurtubise happened to see shortly before he began his intensive research and development work.

Hurtubise is a pure example of the lone inventor, in the tradition of James Watt, Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla. Regarded by some as a half-genius, by others as a half-crackpot, he has unsurpassed persistence and imagination. He also is very careful. The proof that he is very careful is that he is still alive.

A grizzly bear is tremendously, ferociously powerful. Hurtubise realized that he would be wise to test his suit under controlled conditions prior to giving it the ultimate test. He spent seven years, and by his estimate $150,000 Canadian, subjecting the suit to every large, sudden force he could devise. Volunteers have pushed him off cliffs, rammed him with trucks travelling forty kilometres per hour, and assaulted him with logs, arrows and pickaxes. For almost all of the testing, Hurtubise was locked inside the bulky suit, despite being severely claustrophobic.

The suit is a technical wonder, especially when one realizes that Hurtubise had to assemble it mostly from scrounged materials. Among the components:

- titanium plates

- a fireproof rubber exterior

- joints made of chain mail

- a Tek plastic inner shell

- an inner layer of air bags

- nearly a mile of duct tape

For conceiving, building and personally testing the suit, and for keeping it and himself intact the whole while, Troy Hurtubise was awarded the 1998 Ig Nobel Prize in the field of safety engineering.

Hurtubise has continued to do advanced R&D work. He has had unexpected adventures involving, among other things, NASA, the National Hockey League, an invention to separate oil from sand, a tapped phone, a mysterious nocturnal break-in, getting kicked in the crotch on television by comedian Roseanne Barr, a visit from Al Qaeda hijackers and an encounter in a locked room with two Kodiak bears.

He also created a book in which he tells secrets about the most advanced version of his suit, the fruit of fifteen mostly unfunded years of fevered research and development. Here’s a passage that brings together some of the main themes:

Electronically speaking, the M-7 was right out of a movie. It sported an onboard viewing screen, an onboard computer built into the thigh cavity, a bite-bar on the right forearm, a five-way voice-activated radio system and an electronic temperature monitor. For protection against the grizzly’s claws and teeth, the M-7 boasted an entire exoskeleton made up of my newly developed … blunt trauma foam to dissipate the bear’s deadly power. Testing on the M-7 [was] short and sweet. A 30-ton front-end loader in fourth gear smashed me through a non-mortared brick wall and I suffered not a bruise. The world watched the test on CNN, and then came the sheer stupidity that nearly cost me my life, the fire test. My bear research suits were never designed for fire.

Bear Man: The Troy Hurtubise Saga is a magnum opus, the tersely told summary of the man’s yearnings, frustrations, triumphs and philosophy. The book includes many of Hurtubise’s previous writings on these subjects, augmented with a powerful-as-a-riled-up-grizzly collection of previously private photos, philosophy, intellectualizing and emoting.

He shares with us a letter from Her Majesty the Queen, to whom he had sent some lightly fictionalized writings about his personal knowledge of angels. ‘This great lady of ladies found the time to read my novellas and to respond to me in a letter through her Lady in waiting’, he writes. ‘I was so overwhelmed by Her Majesty’s kindness that I dedicated the third novella from the series, The Canadians, in her honour … As for her son, Prince Charles, his letter to me was stamped confidential.’

Bear Man: The Troy Hurtubise Saga makes a lovely gift for any young girl or boy who might some day have to decide unexpectedly whether to devote a lifetime to inventing, testing and informing the world about new ways to protect themselves against grizzly bears while doing no harm to the animals, all the while struggling to lead a good life and set a fine example for the youth both of today and of the future.

Hurtubise’s basic bear-suit research, which brought him the fame and respect he now enjoys, is best seen in the documentary Project Grizzly, produced by the National Film Board of Canada in 1996. You can watch it online at www.nfb.ca/film/project_grizzly.

Bell, Adam Warwick, and Anthony Victor Saunders (2005). ‘Pop-up Device for Deterring an Attacking Animal such as a Bear’. US patent no. 2005/0028720, 10 February.

Hurtubise, Troy (2011). Bear Man: The Troy Hurtubise Saga. Westbrook, ME: Raven House Publishing.

The post-mortem dinosaur kerblam

Seagoing dinosaurs did not explode nearly as often as scientists believed, according to a study called ‘Float, Explode or Sink: Postmortem Fate of Lung-breathing Marine Vertebrates’. The authors, an all-star team of palaeontologists, pathologists and forensic anthropologists from six institutions in Switzerland and Germany, deflated a hypothesis that had for years lain basking in the intellectual shade. They were addressing the underlying question: why are some dino skeletons scattered across an expanse of sea floor, while others remain fairly intact?

The current adventure started with the discovery of an ichthyosaur skeleton, embedded in rock, in northern Switzerland. This skeleton was oriented weirdly, compared with most such fossils: aligned vertically, with its head down, its feet up.

Someone hypothesized that ‘an explosive release of sewer gas’ had ‘propelled the skull into the sediment’. The subsequent research, resulting in the ‘Float, Explode …’ paper, tried to figure out whether that was at all likely.

In so doing, the scientists confronted an idea proposed in 1976 by a palaeontologist named Keller. Keller, noting that beached whales fester in sunlight until putrefaction gases bloat and finally burst them, suggested that sunken sea animal carcasses also gassify and go kerblam. The Swiss/German study summarizes Keller’s idea as follows: ‘It was assumed that carcasses which lie on the sea-floor might have exploded or internal organs and bones erupted, and that in so doing, bones as well as foetuses were ejected and ribs were fractured.’

The team scoured reams of research about what happens to dead dolphins, porpoises, whales, seals, turtles and other sea animals. They say that unless such bodies get stranded on a beach, there’s little evidence and little reason to expect that they explode.

The team presented an early version of their debunkment in 2004 in St Petersburg, Russia, at the Fifth Congress of the Baltic Medico-Legal Association. They called their lecture ‘Did the Ichthyosaurs Explode? A Forensic-medical Contribution to the Taphonomy of Ichthyosaurs’.

Taphonomy, a word that misleadingly suggests both telephones and tap-dancing, is in fact the study of how living things rot and decay. TV crime-scene forensics series present taphonomic adventures week after week, teasing out the likely when, where and how of one or another winsome corpse. This is better. Real-life scientists – Achim Reisdorf, Roman Bux, Daniel Wyler, Mark Benecke and colleagues – had the opportunity to fawn over a corpse way more glamorous than the TV crime drama standard: a sea-monstrous dinosaur.

This is their own take on what actually happened in the mysterious case of the vertical victim: ‘The ichthyosaur sank headfirst into the seafloor because of its centre of gravity, as anatomically similar, comparably preserved specimens suggest. The skull penetrated into the soupy to soft substrate until the fins touched the seafloor.’

A few people disagree. Creation magazine made a video explaining that no scientist can explain the existence of that upside-down dinosaur – that it deals ‘a lethal body blow’ to the theory of evolution. Behold their creative reasoning at http://creation.com/creation-magazine-live-episode-53.

Reisdorf, Achim G., Roman Bux, Daniel Wyler, Mark Benecke, Christian Klug, Michael W. Maisch, Peter Fornaro and Andreas Wetzel (2012). ‘Float, Explode or Sink: Postmortem Fate of Lung-breathing Marine Vertebrates’. Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments 92 (1): 67–81.

Keller, T. (1976). ‘Magen- und Darminhalte von Ichthyosauriern des Süddeutschen Posidonienschiefers’. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte 5: 266–83.

Bux, R., Reisdorf, A., and Ramsthaler, F. (2004). ‘Did the Ichthyosaurs Explode? A Forensic-medical Contribution to the Taphonomy of Ichthyosaurs’. Proceedings of the Fifth Congress of the Baltic Medico-Legal Association, St Petersburg, Russia, 6–9 October, p. 69.

Wetzel, Andreas, and Achim G. Reisdorf (2007). ‘Ichnofabrics Elucidate the Accumulation History of a Condensed Interval Containing a Vertically Emplaced Ichthyosaur Skull’. In Bromley, Richard Granville (ed.). Sediment–Organism Interactions: A Multifaceted Ichnology. Tulsa, Ok.: SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology), special publication no. 88, pp. 241–51.

An improbable innovation

‘A Safety Device for Use in Making a Landing from an Aeroplane or Other Vehicle of the Air’

a/k/a a parachuteless emergency glider, by Hermann W. Williams (US patent no. 1,799,664, granted 1931)

May we recommend

‘Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: SystemATic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials’.

by G.C.S. Smith and J.P. Pell (published in British Medical Journal, 2003)

‘Parachuting for Charity: Is It Worth the Money? A 5-Year Audit of Parachute Injuries in Tayside and the Cost to the NHS’

by C.T. Lee, P. Williams, and W.A. Hadden (published in Injury, 1999)

Send in the clown insurers

Clown insurance is for clowns, not for persons potentially afflicted by them. Insurance companies offer it to clowns because clowns – no matter what you may thoughtlessly think of them – are people, and bad things can happen to anyone. Consider this story, shared by ‘Posadaclown’ on a popular online clowning forum in 2005:

Just had the worst night of my clowning career last night. Took it up seriously a couple of years ago, joined a local troupe who would perform around my locality (Northumberland), and things were going quite well … inbetween the goat shearing and terrier racing, when I managed to spin a few plates, do a bit of slapstick incorporating a farmers daughter and managed to get some great laughs for a comedy routine where I made a rabbit ‘disappear’ before running down my trouser leg and away! Things were going really well until last night when I did a performance at a local club. My family were all there, and my gorgeous new wife, who herself likes to don the red nose and baggy trousers from time to time. Anyway, I did a stunt which involved jumping off a trampoline onto a skateboard, I was supposed to shoot offstage but ended up in the front row, where I managed to land right on top of the mayor’s wife, breaking her leg. The poor woman was in agony and a few in the crowd took exception and beat me quite badly.

Clown insurance exists, as a distinct product category, thanks to the mathematical discipline called risk assessment. Industry researchers calculate that every year enough bad things happen to enough clowns to reliably yield a profit. Clowns, as a group, perform a benefit/cost calculation; that’s why, year after year, they spend money to defend against life’s practical jokes.

The UK boasts several suppliers of insurance for clowns. Blackfriars Insurance Brokers (www.blackfriarsgroup.co.uk/business/insuranceforclowns.html), for one, offers public liability clown insurance of up to £5 million cover. Their website boasts, not unkindly, of ‘products to meet the business and personal insurance needs of clowns’. Blackfriars also offers insurance for those who hire clowns: ‘Clowns employers liability insurance protects the policyholder in respect of your legal liability for personal injury or illness suffered by employees during the course of their employment’.

Foreign clowns, too, can buy clown insurance. Pretty much any clown, anywhere, can join the World Clown Association (worldclown.com). The association, based in the US, offers its members liability insurance ‘with coverage of $1,000,000 per occurrence/$2,000,000 aggregate per event’.

Their insurance application form specifically excludes many of the activities that, one can infer, have proved troublesome.

They will not insure a clown for clowning that involves hypnosis, bouncy castles, hot air balloons, sky diving or competition racing. The application form does not distinguish between the numerous forms of racing – foot, horse, camel, bicycle, ski, cigarette boat, dragster, Spitfire, what-have-you.

Other things too, are verboten for the clown who wants to be protected by the association’s standard clown insurance.

No throwing objects in any manner other than juggling them.

No working with animals, other than ‘performing dogs, doves and rabbits’.

No ‘pyrotechnics, explosives, fireworks or similar materials’. But the association is not a killjoy. It explicitly makes an exception for ‘concussion effects’, ‘flashpots’ and ‘smokepots’.

No copyright infringement (that’s what they call it, though they may mean trademark infringement). The association specifically mentions Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse as examples. In any event, one would do well to seek professional advice before simultaneously wearing a Mickey Mouse costume and a clown suit.

The US is blessed with a large population of clowns. American clowns, unlike their counterparts in much of the world, are blessed with a wide variety of vendors eager to sell off-the-shelf clown insurance. American insurers, in agreement with their British brethren, view clowns as an increasingly specialized species of customer.

Not long ago, hypnotists, fire-eaters and people who do face-painting of children at public events were welcome to purchase standard clown-insurance policies. Then came legal climate change. Now everyone, no matter how clownish they believe themselves to be or not to be, should check the details before binding themselves to any policy that’s designed for clowns.

The life-saving qualities of pizza

A series of Italian research studies suggest that eating pizza just might do good things for a person’s health.

These benefits show up, statistically speaking and seasoned with caveats, among people who eat pizza as pizza. The delightful statistico-medico-pizza effects do not happen so much, the researchers emphasize, for individuals who eat the pizza ingredients individually.

Back in 2001, Dario Giugliano, Francesco Nappo and Ludovico Coppola, at Second University Naples, published a study in the journal Circulation called ‘Pizza and Vegetables Don’t Stick to the Endothelium’. The thrust of their finding was that, unlike many other typical Italian meals, pizza does not necessarily cause clogged blood vessels (atherosclerosis) and death.

Silvano Gallus of the Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche, in Milan, has cooked up several studies about the health effects of ingesting pizza.

In 2003, together with colleagues from Naples, Rome and elsewhere, Gallus published a report called ‘Does Pizza Protect Against Cancer?’, in the International Journal of Cancer. It compares several thousand people who were treated for cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, oesophagus, larynx, colon or rectum with patients who were treated for other, non-cancer ailments. Several hospitals gathered data about what the patients said they habitually ate. The study ends up speaking, in a vague, general way of an ‘apparently favorable effect of pizza on cancer risk in Italy’.

In 2004, in a monograph in the European Journal of Cancer Prevention, Gallus and two colleagues wrote that ‘regular consumption of pizza, one of the most typical Italian foods, showed a reduced risk of digestive tract cancers.’ Later that year, another team anchored by Gallus published ‘Pizza and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction’. As you would expect from the title, its purpose was ‘to evaluate the potential role of pizza consumption on the risk of acute myocardial infarction’. Gallus and his team ‘suggest that pizza consumption is a favourable indicator’ for preventing, or at least not causing, heart attacks.

Gallus is in no way claiming that pizza prevents all ills. A Gallus-led study called ‘Pizza Consumption and the Risk of Breast, Ovarian and Prostate Cancer’ appeared two years later. These types of cancer are thought to arise differently from the kinds believed to be warded off by pizza. The study puts its message bluntly: ‘Our results do not show a relevant role of pizza on the risk of sex hormone-related cancers.’

The Gallus studies all hedge their bets a bit. Each says, one way or another (and here I’m paraphrasing them): ‘Pizza may in fact merely represent a general indicator of the so-called “Mediterranean” diet, which has been shown to have potential health benefits.’

All of this pertains to Italian-made pizza, metabolized in Italy by Italians. No matter how accurate the scientists’ interpretations turn out to be, there’s no guarantee that they hold true for foreign pizza, or for any pizza eaten anywhere by foreigners, or for unmetabolized pizza.

A monograph in the journal Traffic Injury Prevention explains that, whatever the good or bad of eating pizza may be, delivering the pies can put you on a collision course with unhappiness.

Dr Chris McLean and his colleague J. Bernard at Mayday University Hospital, in Croydon, UK, say they were inspired by a 1992 report, in the journal Injury, by Dr M.G. Dorrell of Edgware General Hospital in London. Dorrell ‘described a series of six patients who sustained bony injuries in road traffic accidents during the course of their employment as pizza delivery personnel’. Subsequently, the Pizza and Pasta Association, acting in concert with the government, developed a voluntary code of practice for home delivery individuals, with the goal of reducing or even eliminating pizza/transportation-induced bony and other injuries.

McLean and Bernard, a decade after the Edgeware pizza crack-up study, analysed what happened to three pizza delivery moped drivers who were themselves delivered to Mayday University Hospital. ‘None of them possessed a full UK driver’s license’, write McLean and Bernard, and ‘all three were involved in collisions with automobiles.’ One simply fell off his moped; the other two ‘somersaulted over their moped handlebars’. Piecing together the available evidence, McLean and Bernard tentatively conclude that ‘nonnative workers who lack English language skills and moped driving skills are at increased risk of moped accidents’.

Thus, pizza can most definitely not be ruled out as a nexus of havoc prior to ingestion.

Giugliano, Dario, Francesco Nappo, and Ludovico Coppola (2001). ‘Pizza and Vegetables Don’t Stick to the Endothelium’. Circulation 104 (7): E34–5.

Gallus, Silvano, Cristina Bosetti, Eva Negri, Renato Talamini, Maurizio Montella, Ettore Conti, Silvia Franceschi, and Carlo La Vecchia (2003). ‘Does Pizza Protect Against Cancer?’. International Journal of Cancer 107 (2): 283–4.

Gallus, Silvano, Cristina Bosetti, and Carlo La Vecchia (2004). ‘Mediterranean Diet and Cancer Risk’. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 13 (5): 447–52.

Gallus, Silvano, A. Tavani, and Carlo La Vecchia (2004). ‘Pizza and Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction’. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 58 (11): 1543–6.

Gallus, Silvano, Renato Talamini, Cristina Bosetti, Eva Negri, Maurizio Montella, Silvia Franceschi, A. Giacosa, and Carlo La Vecchia (2006). ‘Pizza Consumption and the Risk of Breast, Ovarian and Prostate Cancer’. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 15 (1): 74–6.

McLean, C. R., and J. Bernard (2003). ‘Ethnicity as a Factor in Pizza Delivery Crashes’. Traffic Injury Prevention 4 (3): 276–7.

Dorrell, M. G. (1992). ‘The Cost of Home Delivery.’ Injury 23 (7): 495–6.

May we recommend

Cannibalism: Ecology and Evolution among Diverse Taxa

by M.A. Elgar and B.J. Crespi (Oxford University Press, 1992)

On page 361 the monograph gets right to the nub of the matter: ‘Cannibalism is a particularly antisocial form of behaviour.’

The smell of cadaverine in the morning

Putrescine and cadaverine, the two most frighteningly named of all chemicals, lurk in our mouths all day, every day. This simple fact emerged in 2003 when Professor Michael Cooke BSc PhD CChem FRSC Eur Chem, of the Centre for Chemical Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, and two colleagues published a delectable horror story of a study called ‘Time Profile of Putrescine, Cadaverine, Indole and Skatole in Human Saliva’. It appeared in the Archives of Oral Biology. That journal – surprisingly, given its content – is a regular haunt of only a tiny fraction of the world’s horror fiction enthusiasts.

Professor Cooke and his companions imply that other chemists had grown discouraged at the prospect of doing a time profile of putrescine, cadaverine, indole and skatole in human saliva. The odour of saliva is intensely bland, compared to that of its most apallingly stenched components, and in a certain chemical sense, stable. An American group, they say, ‘reported their inability to increase the odour of saliva’. But Cooke and his team gave it a go and succeeded.

In isolation, putrescine and cadaverine are anything but bland. They smell even worse than their names suggest. The one was so named because it evokes, and is involved in, the putrefaction of flesh. The other’s name suggests, deliberately and accurately, the stench of rotting corpses. Biochemically, the pair are cousins, and though not inseparable, are often found in each other’s company. Together with their mundane-sounding (yet also pungent) companions indole and skatole, putrescine and cadaverine are formed by ‘bacterial putrefaction of saliva in the oral cavity’, explains the study.

Here’s how Cooke and his companions went about monitoring their presence.

Twelve dentally healthy volunteers, three women and nine men, supplied the spit. The scientists took pains to collect and handle it properly. They explain that ‘The unstimulated saliva was expectorated into a glass vial coated with 5 mg of NaF [sodium fluoride] to inhibit further [chemical reactions].’

The results appear in a simple graph. Its lines and data points tell an engrossing tale: the ‘mean concentration of cadaverine, putrescine and indole in saliva throughout the day’. (Skatole, though mentioned in the study’s title, never appears in measurable amounts.)

Cadaverine, putrescine and indole levels, having built up overnight, are high when we awaken. But ‘they are rapidly reduced by the combined action of eating breakfast and oral cleaning’. Then until the beginning of the work day (around 9:00 am) the levels remain steady.

The rest of the day has its ups and downs. Cadaverine, putrescine and indole levels rise until mid-morning, then slowly decline. Noontime brings dramatic change – the amounts are ‘reduced by the mechanical action of chewing involved in the ingestion of lunch’. After lunch, the levels rise pretty steadily until it’s time to knock off work.

Bacterial putrefaction in twelve subjects in ‘good general and oral health’ who had consumed ‘a controlled diet the evening before sample collection and during the saliva collection day’

The researchers stopped collecting data every day at 5:00 pm. What happens between then and dawn retains, slightly, an air of mystery.

Cooke, Michael, N. Leeves, and C. White (2003). ‘Time Profile of Putrescine, Cadaverine, Indole and Skatole in Human Saliva’. Archives of Oral Biology 48 (4): 323–7.

The giant who played with dead dolls

Frances Glessner Lee, the giant astride the world of miniature crime scenes, died nearly fifty years ago. Lee built a collection of what she called ‘nutshell studies’, each a tiny, high-precision recreation of a room in which a murder had been committed.

Each featured a little victim, in or on whom the wee murder weapon was embedded or enwrapped. The many lavishly grim elements of each diorama were, mostly, copped and composited from stories of real crimes.

Lee and her nutshell studies have a context. She endowed an entire, entirely new programme at Harvard Medical School: the department of legal medicine. The concocted crime scenes served as its mesmerizing centre of activity.

The authorities knew that Lee manufactured her evidence from whole cloth, sliced wallpaper, glass, wood, paint and other materials. They knew that she bankrolled the entire operation. They knew that she enlisted the aid of a carpenter, a pricey interior decorating firm and a company that makes doll’s houses. They knew that she conspired with a large number of police officers, whom she plied with lavish meals and strong drink. No one entirely figured out her motive.

Lee, the heiress of a wealthy Chicago farming-equipment manufacturing family, chose the department’s first (and only) leader – a dashing male doctor, her brother’s Harvard classmate, whom she had kept very much in mind during the decades that preceded her inheritance.

Several times a year, she would invite and fund police officers and medical examiners from across the US, thirty or forty at a time, to travel to her Harvard seminar in homicide investigation. Everyone would examine and discuss the miniature rooms, then go and dine together in splendour at one of Boston’s finest hotels. Lee even bought the hotel a costly set of china for use exclusively at these dinners.

Author-photographer Corinne May Botz crafted a book entitled The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Originally published in 2004, it shows appropriately disturbing close-up photos of the artificial crime scenes. Botz also reproduces the short descriptive texts that each visiting law-enforcement official was expected to read in connection with his (they were, apparently, all men) visit to Lee and her educational programme.

The US National Library of Medicine has put several of Botz’s photos online (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/visibleproofs/galleries/biographies/lee.html). A documentary film, Of Dolls and Murder, came out in 2012, with creepy John Waters narrating.

Lee-style fantastically detailed miniature crime-scene recreations never became a standard tool for crime-scene investigators. But their spirit lives on. There is now something of a police vogue for crime incident diagramming software, polyflex forensic mannequins and mini tubular dowel crime-scene reconstruction kits.

The Harvard department of legal medicine did not long survive the passing of its founder and funder. Its crown jewels, the little rooms, went south and now reside at the Maryland Medical Examiner’s Office in Baltimore.

Botz, Corinne May (2004). The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death: Essays and Photography. New York: Monacelli Press.

Eckert, W.G., (1981). ‘Miniature Crime Scenes: A Novel Use in Crime Seminars’. American Journal of Forensic Medicine & Pathology 2 (4): 365–8.

Lee, Frances Glessner (1952). ‘Legal Medicine at Harvard University’. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science 42 (5): 674–8.

In brief

‘Spatial Patterning of Vulture Scavenged Human Remains’

by M. Katherine Spradley, Michelle D. Hamilton and Alberto Giordano (published in Forensic Science International, 2011)

The authors, at Texas State University-San Marcos, report: ‘After the initial appearance of the vultures, the body was reduced from a fully-fleshed individual to a skeleton within only 5 h.’

Fast robust automated brain extraction

Scientists marvel at how other scientists – the ones who study something other than what they themselves study – give strange meanings to common words.

Evan Shellshear, at Fraunhofer Chalmers Centre in Gothenburg, sent me an example, a study called ‘Fast Robust Automated Brain Extraction’.

Shellshear said: ‘I stumbled across this article somehow [whilst] looking for optimal code to quickly compute the distance between two triangles in three-dimension space for computer games. It sounds almost like something out of a game itself … After careful reading, [the paper] justifies the initially shocking title.’ The author is Stephen M. Smith who, back in 2002 when the paper came out, was at the department of clinical neurology at Oxford University’s John Radcliffe Hospital, and is now a professor of biomedical engineering.

Certain details might give you the willies, if you are unpractised in the ways and words of Dr Smith’s line of research. Especially in this age when zombies are so much in the public mind. One section of the paper carries the conceivably disturbing headline ‘Overview of the brain extraction method’.

The abstract could plausibly have been written by Dr Phibes or any of a hundred other horror-movie body-part-snatching researchers. It says: ‘Brain Extraction Tool (BET) … is very fast … [I give] the results of extensive quantitative testing against “gold-standard” hand segmentations, and two other popular automated methods.’

That phrase ‘hand segmentations’ suggests lots of lengthy, laborious tedium. But in some contexts ‘hand segmentations’ could be a handy euphemism – in a discussion, say, of how to pluck out only the choicest parts of a cadaver’s brain after you’ve smashed open its skull.

Smith acknowledges that doing his deed by hand has one advantage over letting a computer do it: ‘Manual brain/non-brain segmentation methods are, as a result of the complex information understanding involved, probably more accurate than fully automated methods are ever likely to achieve.’

But he explains that, financially, it’s better when a computer does the dirty work. ‘There are serious enough problems with manual segmentation’, he warns. ‘The first problem is time cost. Manual brain/non-brain segmentation typically takes between 15 minutes and two hours.’

‘Fast Robust Automated Brain Extraction’ is not about sucking brains out of people’s skulls, alas.

Published in a journal called Human Brain Mapping, it’s about perceiving more clearly what’s in the pictures produced by modern imaging machines. These magnificent devices give such a profusion of detail that doctors sometimes can’t tell where one body part ends and another begins.

Smith explains that in a brain scan, ‘the high resolution magnetic resonance image will probably contain a considerable amount [of] eyeballs, skin, fat, muscle, etc’. The image can become more understandable, more useful ‘if these non-brain parts of the image can be automatically removed’.

Thus a report that gives the heebie-jeebies to some scientists gives, instead, hope and cheer to those who have the specialized brains to appreciate it.

Smith, Stephen M. (2002). ‘Fast Robust Automated Brain Extraction’. Human Brain Mapping 17: 143–55.

In brief

‘Good Samaritan Surgeon Wrongly Accused of Contributing to President Lincoln’s Death: An Experimental Study of the President’s Fatal Wound’

by J.K. Lattimer and A. Laidlaw (published in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 1996)

The authors, who are at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University in New York, explain that ‘When President Abraham Lincoln was shot in the back of the head at Ford’s Theater in Washinton, DC, on April 14, 1865, he was immediately rendered unconscious and apneic. Doctor Charles A. Leale, an Army surgeon, who had special training in the care of brain injuries, rushed to Lincoln’s assistance… thrusting his finger into the brain through the finger hole.’

Dead mule specialities

Jerry Leath Mills reigns as the unchallenged authority on the subject of dead mules in twentieth-century American southern literature.

Professor Mills established his reputation – almost instantly – in 1996, with the publication of a long essay called ‘Equine Gothic: The Dead Mule as Generic Signifier in Southern Literature of the Twentieth Century’. He retired that year after three decades of teaching English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His dead mule treatise appeared in the Southern Literary Journal.

‘Equine Gothic’ reads as if the accumulated dead mules had been stewing in Mills’s head, and were at last in a fit state for him to ladle out. ‘My survey of around 30 prominent 20th-century southern authors’, Mills writes, ‘has led me to conclude … that there is indeed a single, simple, litmus-like test for the quality of southernness in literature, one easily formulated into a question to be asked of any literary text and whose answer may be taken as definitive, delimiting and final. The test is: Is there a dead mule in it?’

‘Drowning – Faulkner’s most commonly employed means of dispatch for the mules in his work’ from ‘The Dead Mule Rides Again’ (drawing by Bruce Strauch)

He organized his findings ‘coroner-wise’, listing the different causes of southern literary mule death. These include:

- ‘Beating’. In Larry Brown’s novel Dirty Work

- ‘Coal dust and mine gasses’. In Hubert J. Davis’s short story ‘The Multilingual Mule’

- ‘Collision with railroad train’. In William Faulkner’s ‘Mule in the Yard’

- ‘Drowning’. In many works by many authors

- ‘Decapitation by irate opera singer’. In Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing

- ‘Falls from cliffs’. In Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian

In Mills’s telling, McCarthy is an impresario of fictional mule slaughter. In Blood Meridian alone, ‘Mules are shot, roasted, drowned, knifed, and slain by thirst; but the largest number, fifty …, plummet from a single cliff during an ambush, performing an almost choreographic display of motion and color.’

Other mules, in other stories by other southerners, exit by freezing, hanging, gunshot wounds, a ‘fall into subterranean cavity’, rabies, stab wounds, ‘something called vesicular stomatitis’, thirst, overwork or, when all else failed to fell them, ‘unspecified natural causes’.

Mills expresses wonder at all this belletristic mule mortality. During his own life lived in the American south, he says, ‘I have never laid eyes on an actual dead mule.’

Through his very bookishness, he came to realize that others shared this particular obliviousness. ‘I have been gratified of late to discover that I am not alone’, he beams. ‘I am pleased to read, in an article in Scientific American magazine, that the British army harbors a proverbial belief that “one never sees a dead mule”.’

I must report, though, that the Scientific American article goes on to say about the British army: ‘During World War I many men made the acquaintance of mules for the first time, and many mules had their first encounter with partially trained drivers … [This] ended only too often in events belying the tradition.’

Mills, Jerry Leath (1996). ‘Equine Gothic: The Dead Mule as Generic Signifier in Southern Literature of the Twentieth Century’. Southern Literary Journal 29 (1): 2–17.

— (2000). ‘The Dead Mule Rides Again’. Southern Cultures 6 (4): 11–34.

Savory, Theodore H. (1970). ‘The Mule’. Scientific American (December): 102–9.