Four

Bones, Foreskins, Armpits, Slime

In brief

‘The Swedish Pimple: Or, Thoughts on Specialization’

by Jeffrey D. Bernhard (published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 1995)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Explain that itch • Army dandruff • What colour the foreskin • Fingers and pigment, perhaps • Botox for the fetid • Facial hair vs decollatage • Harry Potter, recessively • Kangaroo, harp, infant • Gay anticlockwise scalp hair-whorl rotation • Influence of fingers in eyes • Nude doll with gonorrhoea • Slimeball’s gooey power • White hair, too suddenly • Cheek dimples counted and made • Soy sauce hair

The apparent source of an itch

‘Observations during Itch-Inducing Lecture’ is a study published by German researchers in the year 2000. It delivers exactly what the title promises.

Professor Uwe Gieler at Justus-Liebig University in Giessen and two colleagues begin with the basics: ‘Itching is defined as a sensation associated with an impulse to scratch.’

They invited people to attend a public lecture called ‘Itching – What’s Behind It?’ The lecture was purportedly recorded for broadcast on television. In fact, the TV cameras were there to record what the audience did – whether people scratched themselves, or failed to scratch themselves.

Method of soliciting and observing participants for the lecture

The lecture had two parts, the first filled with slides of fleas, mites, scratch marks on skin and other visual stimuli that the scientists hoped would ‘induce itching’. The remainder of the lecture presented photos of babies, soft skin and other items meant to ‘induce relaxation and a sense of well-being’.

The experiment was to some extent a success. Audience members, on average, scratched themselves more frequently during the itch-provoking part of the lecture. However, because the audience was small, the scientists hesitate to draw any firm conclusion from what happened.

Five years earlier, Clifton W. Mitchell published a treatise called ‘Effects of Subliminally Presented Auditory Suggestions of Itching on Scratching Behavior’. It describes his doctoral thesis research at Indiana State University.

For Mitchell, itching and scratching were but a means to an end. His main interest was subliminal perception. His stated intent was ‘to create an experimental situation closely analogous to that encountered in commercially available subliminal self-help audiotapes’.

Dr Mitchell had volunteers listen to a specially prepared eleven-minute-long recording of recited ‘suggestions of itching’. The report does not specify the nature of these suggestions, other than to say that they were recorded at a level so low that it ‘prohibit[ed] conscious detection of spoken words’. Mitchell buried these whisperings beneath a loud soundtrack of what he describes as ‘new-age style music’.

A different group of volunteers listened to a recording of just the music.

A third group heard a recording of someone simply, loudly making suggestions about itching. The technical term for this explicit prompting, the report informs us, is ‘supraliminal suggestions’.

Mitchell added extra scientific rigour: ‘To distract participants from the purpose of the experiment, a biofeedback-type headband with bogus sensors and wiring was fitted around the head.’

He video-recorded the test subjects, then evaluated the recordings to see who scratched themselves, and how often.

The report presents the results of the experiment, condensed into a concise, readable table that is labelled ‘Means and standard deviation for number of scratching-type behavior observed for each group across phases’. Those results were a bit paradoxical. Those who listened to the overt itching messages scratched themselves least, those who listened to the pure music scratched most.

There was, Mitchell reports finally, ‘no evidence’ that listening to subliminally presented auditory suggestions of itching led to an increase in scratching behaviour.

Niemeier, Volker, Jörg Kupfer and Uwe Gieler (2000). ‘Observations during Itch-inducing Lecture’. Dermatology and Psychosomatics 1 (1 suppl.): 15–8.

Mitchell, Clifton W. (1995). ‘Effects of Subliminally Presented Auditory Suggestions of Itching on Scratching Behavior’. Perceptual and Motor Skills 80 (1): 87–96.

May we recommend

‘Severe Infestation of a She-Ass with the Cat Flea Ctenocephalides felis felis (Bouche, 1835)’

by I. Yerhuham and O. Koren (published in Veterinary Parasitology, 2003)

Dandruff in the army of Pakistan: a comprehensive look

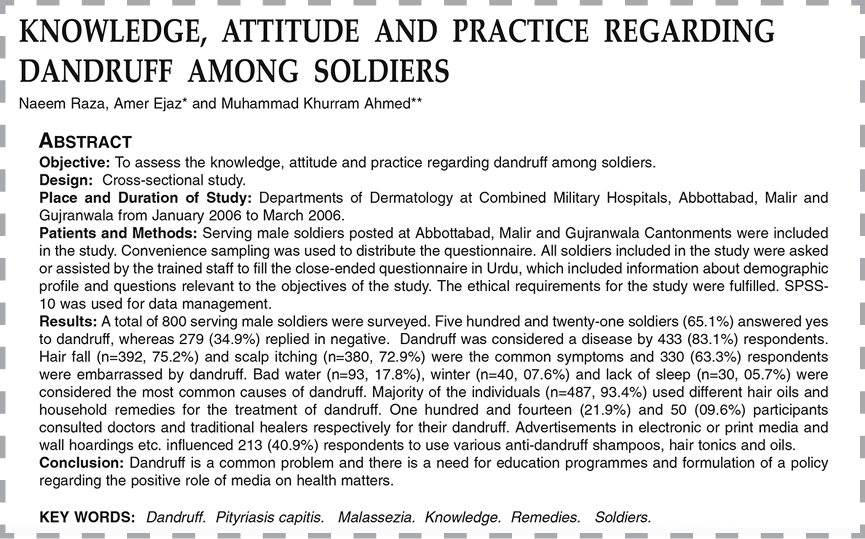

Public knowledge about dandruff in Pakistan’s army comes mainly from a study called ‘Knowledge, Attitude and Practice regarding Dandruff among Soldiers’, written by Naeem Raza, Amer Ejaz and Muhammad Khurram Ahmed, published in 2007 in the Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons – Pakistan.

Raza, Ejaz and Ahmed surveyed eight hundred male soldiers of all ranks, ascertaining each soldier’s knowledge about, and personal experience with, dandruff. The survey was ‘designed keeping in mind the general taboos of our region about dandruff, which included visits to doctors, homeopathic physicians or “hakims”, use of oils, any home-made remedies or commercial products’.

If this sampling of soldiers was truly representative, we now know that approximately 65 percent of Pakistani soldiers have, or have had, dandruff ‘either permanently or periodically’. ‘Almost two thirds of the respondents stated to remain tense and embarrassed because of their dandruff.’ Noting that the ‘media has played an important role in making people think like that’, the study concludes with a recommendation. Healthcare professionals should make a greater effort to educate the populace.

Both the numbers and the reactions are typical of the region and the world, according to a study published three years later in the Indian Journal of Dermatology, called ‘Dandruff: The Most Commercially Exploited Skin Disease’.

The Indian report sketches the underlying situation: ‘Dandruff is a common scalp disorder affecting almost half of the population at the pre-pubertal age and of any gender and ethnicity. No population in any geographical region would have passed through freely without being affected by dandruff at some stage in their life.’ It helpfully fills in the etymology. ‘The word dandruff (dandruff, dandriffe) is of Anglo-Saxon origin, a combination of “tan” meaning “tetter” and “drof” meaning “dirty” ’.

The Pakistan military report cites a 1990 monograph called ‘The History of Dandruff and Dandruff in History. A Homage to Raymond Sabouraud’. That homage was written by Didier Saint-Léger of l’Oréal in Aulnay-sous-Bois, France, and published in the journal Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. Saint-Léger explains that Raymond Jacques Adrien Sabouraud (1864–1938), a French dermatologist, painter and sculptor, is the dominant figure in humanity’s effort to understand dandruff.

Saint-Léger shares how dandruff figured in Sabouraud’s greatness: ‘In one of his books, written at the beginning of this century, Raymond Sabouraud devotes some 280 pages to the history of dandruff. Their reading illustrates how, from the Greeks to Sabouraud’s era, this desquamative disease has been subjected to endless doctrinal and scientific conflicts.’

A medical book written during Raymond Sabouraud’s lifetime speaks admiringly of the man: ‘It is said that Sabouraud can tell your moral character, the amount of your yearly income and what you have eaten for breakfast by looking at the root of one of your hairs.’

Raza, Naeem, Amer Ejaz and Muhammad Khurram Ahmed (2007). ‘Knowledge, Attitude and Practice regarding Dandruff among Soldiers’. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons – Pakistan 17 (3): 128–31.

Ranganathan, S., and T. Mukhopadhyay ‘Dandruff: The Most Commercially Exploited Skin Disease’. Indian Journal of Dermatology 55 (2): 130–4.

Saint-Léger, Didier (1990). ‘The History of Dandruff and Dandruff in History: An Homage to Raymond Sabouraud’. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie 117 (1): 23–7.

Thompson, Ralph Leroy (1908). Glimpses of Medical Europe. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, p. 145.

May we recommend

‘The History of Freckles in Art’

by H.W. Seimens (published in Der Hautarzt, 1967)

Colourful foreskin research

Bryan B. Fuller is the world’s top expert on skin colour in human foreskins.

Fuller’s foreskin research was for a long time based at the University of Oklahoma. He then became the founder and CEO of DermaMedics (www.dermamedics.com).

A research paper Fuller co-authored with four colleagues in 1990 is the most frequently cited study on the topic of foreskin colour. Entitled ‘The Relationship between Tyrosinase Activity and Skin Color in Human Foreskins’, it appeared in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology. It makes lively reading.

The scientists pre-select their foreskins on the basis of race. The paper explains: ‘The race of the child was determined from the race of both parents. Foreskins were only used from children whose parents were either racially caucasian or black. No foreskins from racially mixed marriages were used.’

The Fuller process of preparing and utilizing a foreskin is complex.

Seen from the point of view of a foreskin, this is a many-stage adventure. First, the foreskin is surgically removed from its birthplace. Then it is placed on a gauze pad that’s been saturated with a fluid called ‘Hank’s balanced salt solution’. It is then trimmed and sliced into five-square-millimetre chunks. Then each chunk is homogenized three times. It is then sonicated three times. (You may not be familiar with sonication. Sonication, in the words of the Hielscher Ultrasonics company, which makes sonicators, is ‘a very effective method for the mixing, homogenizing, emulsifying, dispersing, disintegrating, and degassing of liquids by means of ultrasonic cavitation’.) The foreskin bits are then frozen, then centrifuged, then sonicated once more.

By this time, the foreskin has been through a lot. But the adventure is really just beginning. Now, at last, the foreskin bits get analysed, but that is a story for another time.

Fuller’s patent (US patent no. 5,589,161) for using foreskins to test skin-tanning solutions is the ne plus ultra on how to use foreskins to test skin-tanning solutions.

During his academic days, one of Fuller’s main aims, according to his website, was ‘to develop skin care products which can stimulate melanin production (tanning) in fair-skinned individuals’. Five of his eleven foreskin-related patents, though, were about how to make skin become lighter. One, called ‘Method for Causing Skin Lightening’, features a 1,300-word exposition about foreskins.

Scientists of an earlier generation fondly recall D.A. Pious and R.N. Hamburger’s study of fifty cultures of human foreskin cells, published in 1964. Pious and Hamburger, however, had little to say about the colour of the foreskins.

And of earlier times, there is little on the record. Most disappointing is the fact that foreskin colour is not mentioned at all in Frederick M. Hodges’ instant-classic of a report on ‘The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome’, which was published in 2001 in the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. A Fuller account is wanted.

Fuller, Bryan B. (1996). ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’. US patent no. 5,589,161, 31 December.

— (2000). ‘Method for Causing Skin Lightening’. US patent no. 6,110,448, 29 August.

Pious, D.A., R.N. Hamburger and S.E. Miles (1964). ‘Clonal Growth of Primary Human Cell Cultures’. Experimental Cell Research 33 (3): 495–507.

Hodges, Frederick M. (2001). ‘The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme’. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 75 (3): 375–405.

In brief

A fuller partial accounting of Bryan B. Fuller’s patents and patents pending:

- ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’.

- US patent no. 5,540,914, 30 July 1996.

- ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’.

- US patent no. 5,554,359, 10 September 1996.

- ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’.

- US patent no. 5,589,161, 31 December 1996.

- ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’.

- US patent no. 5,591,423, 7 January 1997.

- ‘Pigmentation Enhancer and Method’.

- US patent no. 5,628,987, 13 May 1997.

- ‘Composition for Causing Skin Lightening’.

- US patent no. 5,879,665, 9 March 1999.

- ‘Enhancement of Skin Pigmentation by Prostaglandins’.

- US patent no. 5,905,091, 18 May 1999.

- ‘Method of Lightening Skin’.

- US patent no. 5,919,436, 6 July 1999.

- ‘Method of Lightening Skin’.

- US patent no. 5,989,576, 23 November 1999.

- ‘Composition for Causing Skin Lightening’.

- US patent no. 6,096,295, 1 August 2000.

- ‘Method for Causing Skin Lightening’.

- US patent no. 6,110,448, 29 August 2000.

Research spotlight

‘Second to Fourth Digit Ratio, Sexual Selection, and Skin Colour’

by John T. Manning, Peter E. Bundred and Frances M. Mather (published in Evolution and Human Behavior, 2004)

The authors, at the University of Central Lancashire and the University of Liverpool, write: ‘Skin pigment may be related to mate choice, marriage systems, resistance to micoorganisms, and photoprotection. Here we use the second to fourth digit ratio (2D:4D) to disentangle the relationships.’

In expensively good odour

Botox – a/k/a ‘botulinum toxin’ – has had a curious reputation with the public. First it was feared: it can kill, after all. Then it was cheered: fashionable femmes et hommes were delighted to hear that something with a hint of danger could make their wrinkles vanish. Now we are on the verge of a third and rather different wave of acclaim.

For a long time, only horror film fans, physicians and hypochondriacs were lovingly familiar with the basics about botulinum toxin. Everyone else would hear mention of it only occasionally – whenever the food-borne illness botulism struck down some unhappy soul. The US Centers For Disease Control and Prevention put out a concise description of the illness and its cause: ‘Botulism is a rare but serious paralytic illness caused by a nerve toxin that is produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum.’

As all up-to-date celebrity worshippers know, one particular variety of botulinum toxin – called ‘botulinum toxin A’ – turned out to be useful in a cosmetically valuable way. Botulinum toxin A has other medical uses, too. One of them, the control of excessive, by-the-bucketful underarm sweating, inspired the notion that botulinum toxin might be useful in combating nasty armpit odour.

The notion was put to the test using T-shirts, sniff tests and volunteers who allowed doctors to inject botulinum toxin A into one armpit and a salt solution into the other.

This is specialized research, and discussing it calls for a bit of specialized vocabulary. Bromidrosis is a word familiar to physicians, to pedants and to some of the people who suffer from bromidrosis. It is especially familiar to those sufferers who have consulted a pedant or a physician. Bromidrosis means ‘fetid or foul-smelling perspiration’. The word axillary means ‘having to do with the armpit’.

I mention these two obscure words – bromidrosis and axillary – because Drs Marc Heckmann, Bianca Teichmann and Bettina M. Pause of the Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Munich, and Gerd Plewig of Christian-Albrecht-University in Kiel, use them in describing their volunteers. The report says that ‘although the volunteers had no history of bromidrosis, the axillary odor was clearly rated as unpleasant prior to treatment’.

T-shirt sniff tests were performed before, and again seven days after, the botox-in-the-armpit injections. The results, report the doctors, were dramatic: ‘Apart from reduced odor intensity, axillae treated with botulinum toxin A were also rated as smelling less unpleasant or literally more pleasant, which means an improvement in the quality of body odor. Presently, any explanation for this phenomenon can only be highly speculative.’

We see here the birth of a tentative new rule of thumb: what doesn’t kill you makes you smoother, and less stinky.

Heckmann, Marc, Bianca Teichmann, Bettina M. Pause, and Gerd Plewig (2003). ‘Amelioration of Body Odor After Intracutaneous Axillary Injection of Botulinum Toxin A’. Archives of Dermatology 139 (1): 57–9.

In brief

‘Self-referent Phenotype Matching in a Brood Parasite: The Armpit Effect in Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus alter)’

by Mark E. Hauber, Paul W. Sherman and Dóra Paprika (published in Animal Cognition, 2000)

Losing by a whisker

Not being a barber, and not having had an adulthood that spanned 130 years, Dwight E. Robinson was in no position to report firsthand the frequency of changes in relative prevalence of sideburns, moustaches and beards in London during the years 1842–1972. He used an indirect source: issues of the Illustrated London News published during that time.

Robinson, a business professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, gathered his findings about those findings into a study that he called ‘Fashions in Shaving and Trimming of the Beard: The Men of the Illustrated London News, 1842–1972’. It was published not in Britain but in the American Journal of Sociology, in 1976.

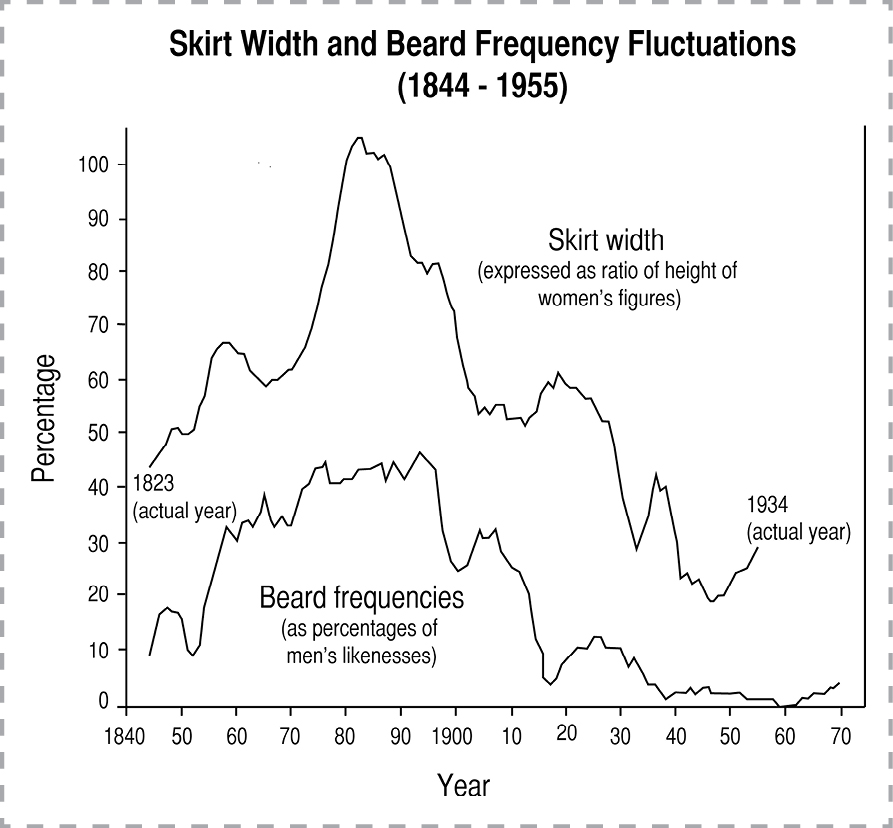

Robinson used and, he says, improved upon a general analytic technique pioneered by Jane Richardson and Alfred L. Kroeber, who in 1940 ‘measured annual fluctuations in width and length of skirts, waistlines and decolletage as ratios to women’s heights’.

‘My procedure for gathering data’, Robinson explains, ‘was, quite literally, to take a head count, determining for any one year the comparative frequencies of men’s choices among five major features of barbering: sideburns alone, sideburns and moustache in combination, beard (a category that included any amount of whiskers centring on the chin), moustache alone, and clean shavenness’. For the mathematically inclined, Robinson notes that ‘the number of clean-shaven men in any year is by definition the reciprocal of the sum of those in the four whisker categories’.

Intent on choosing data that would accurately reflect the reality of Londoners’ facial hair, Robinson excluded photos of groups (because some faces might appear only partially, or in misleading angles), royalty (because royals receive more press coverage, if not necessarily more hair, than the general populace), advertisements and ‘pictures of non-Europeans’. One graph shows, beginning in the year 1885, a stark, almost unceasing rise in clean-shavenness.

Sideburns decline until about the year 1920, thereafter making only negligible appearances. Beards, too, hit bottom in 1920, but quasi-periodically grow back to modest popularity.

In that hair-oilshed year 1921, moustaches reach their all-time peak, adorning nearly 60 percent of the non-grouped, non-royal, non-advertised, non-non-European men appearing in the Illustrated London News. Thereafter, moustaches dominate all other forms of facial hair.

In one provocative graph, Robinson plots two grand, 115-year-long, rising-and-falling waves. One represents women’s skirt width (in proportion to the women’s height). The other shows the pervasiveness of beards among the male population. The skirt-width-ratio wave precedes the beard wave by a gap of twenty-one years. Robinson says the data reveals that ‘men are just as subject to fashion’s influence as women’.

The monograph notes: ‘Skirt width (1823–1934) and beard frequency fluctuations (1844-1955), five-year moving averages. The time scales of the two curves have been positioned to allow for assumed 21-year lead in skirt fluctuations possibly related to comparative youthfulness of subjects’.

Fashion tells just part of the story. A quarter century after Robinson’s analysis, an independent, aptly-named scholar – the Irish-born, America-adopted Nigel Barber – published a study in which he reports that: ‘Men shave their mustaches, possibly to convey an impression of trustworthiness, when the marriage market is weak’.

Robinson, Dwight E. (1976). ‘Fashions in Shaving and Trimming of the Beard: The Men of the Illustrated London News, 1842–1972’. American Journal of Sociology 81 (5): 1133–41.

Richardson, Jane, and Alfred L. Kroeber (1940). ‘Three Centuries of Women’s Dress Fashions: A Quantitative Analysis.’ Anthropological Records 5 (2): 111–54.

Barber, Nigel (2001). ‘Mustache Fashion Covaries with a Good Marriage Market for Women’. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior 25 (4): 261–72.

May we recommend

‘Harry Potter and the Recessive Allele’

by J.M. Craig, R. Dow and M. Aitken (published in Nature, 2005)

‘Duty of Care to the Undiagnosed Patient: Ethical Imperative, or Just a Load of Hogwarts?’

by Erle C.H. Lim, Amy M.L. Quek and Raymond C.S. Seet (published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2006)

Kangaroo care

You might think that an Israeli Medical Association report called ‘Combining Kangaroo Care and Live Harp Music Therapy in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Setting’ is the first medical study of the combined effects, on newborns, of kangaroo care and music therapy. Not so.

The invention of kangaroo care (also called kangaroo therapy) is widely attributed to a pair of doctors in Colombia in the late 1970s. Initially, both the idea and the name triggered scepticism. Thus the appearance in 1990 of a paper called ‘Kangaroo Care: Not a Useless Therapy’, in a magazine published by America’s National Association of Neonatal Nurses.

The idea of kangaroo care is for premature babies to spend most of their time being held or pressed against the mother, the two maintaining direct ‘skin-to-skin’ contact. This was meant as a substitute for incubators in places where those were unavailable. Later, some doctors and nurses began recommending that even the most modern hospitals adopt the practice.

Eventually came attempts to see whether – or not – kangaroo care produces good effects. Research journals began publishing studies, including the provocative ‘Kangaroo Care Modifies Preterm Infant Heart Rate Variability in Response to Heel Stick Pain: Pilot Study’.

Then someone got the idea of adding music. Researchers at several institutions in Taiwan combined forces to perform an experiment, documented in a 2006 paper, ‘Randomized Controlled Trial of Music during Kangaroo Care on Maternal State Anxiety and Preterm Infants’ Responses’, in the International Journal of Nursing Studies. The experimenters had mothers and premature babies snuggle skin-to-skin while listening to recorded music emanated, for sixty minutes, from a Philips AZ-1103 ‘ghetto blaster’. At the same time, other mothers and preemies neither snuggled skin-to-skin nor heard recorded music.

The Taiwan researchers found that the kangaroo’ed babies slept a bit more than the non-kangaroo’ed babies, and cried a bit less. And, they say, the kangarooing mothers gradually felt ever-so-slightly lessened anxiety. As for the babies’ health – the main reason people recommend kangaroo care – they reported ‘no significant difference on infants’ physiologic responses’ between those who got kangarooing and music, and those who did not.

The new Israeli kangaroo-plus-harp-music study also reports that their particular ‘combined therapy had no apparent effect on the tested infants’ physiological responses or behavioural state’. But a similar study – which the Israeli study does not mention – done in Finland and published online a year earlier by the Nordic Journal of Music Therapy reported that kangaroo therapy accompanied by live harp music ‘did’ affect the medical state of the child. The Finns say that it ‘decreased the pulse, slowed down the respiration and increased the transcutaneous O2 saturation’, and ‘affected the blood pressure significantly’.

And so doctors and nurses must await further research before they know the value of prescribing kangaroo care with live harp music.

Schlez, Ayelet, Ita Litmanovitz, Sofia Bauer, Tzipora Dolfin, Rivka Regev and Shmuel Arnon (2011). ‘Combining Kangaroo Care and Live Harp Music Therapy in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Setting’. Israeli Medical Association Journal 13 (6): 354–8.

Jorgensen, K.M. (1999). ‘Kangaroo Care: Not a Useless Therapy’. Central Lines 15 (3): 22.

Cong, Xiaomei, Susan M. Ludington-Hoe, Gail McCain and Pingfu Fu (2009). ‘Kangaroo Care Modifies Preterm Infant Heart Rate Variability in Response to Heel Stick Pain: Pilot Study’. Early Human Development 85 (9): 561–7.

Lai, Hui-Ling, Chia-Jung Chen, Tai-Chu Peng, Fwu-Mei Chang, Mei-Lin Hsieh, Hsiao-Yen Huang and Shu-Chuan Chang (2006). ‘Randomized Controlled Trial of Music During Kangaroo Care on Maternal State Anxiety and Preterm Infants’ Responses’. International Journal of Nursing Studies 43 (2): 139–46.

Teckenberg-Jansson, Pia, Minna Huotilainen, Tarja Pölkki, Jari Lipsanen and Anna-Liisa Järvenpää (2011). ‘Rapid Effects of Neonatal Music Therapy Combined with Kangaroo Care on Prematurely-Born Infants’. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy 20 (1): 22–42.

Swirling sexual positions

Amid the swirls of controversy that buffet other sexuality researchers, one man focuses, quietly, on swirls. In a report called ‘Excess of Counterclockwise Scalp Hair-Whorl Rotation in Homosexual Men’, Dr Amar J.S. Klar announces a subtle discovery. ‘This is the first study’, he writes, ‘that shows a highly significant association of biologically specified counterclockwise hair-whorl rotation and homosexuality in a considerable proportion of men in samples enriched in gays.’ Klar heads the developmental genetics section of the Gene Regulation and Chromosome Biology Laboratory at the US National Cancer Institute in Frederick, Maryland. His hair-swirl study appears in a 2004 issue of the Journal of Genetics.

The phenomenon is easy to overlook. Klar explains: ‘Since the hair whorl is found at the top (“crown”) of the head and thereby it is difficult to observe one’s own whorl and the direction of orientation is seemingly an unimportant feature, most people are oblivious to the direction of their hair-whorl rotation. It takes two mirrors to observe one’s own hair-whorl.’ His monograph includes a photograph showing the ‘scalp hair whorl of an anonymous man selected from the general public’, and directs the reader to hold that picture in front of a mirror in order to ‘appreciate the counterclockwise orientation’.

How difficult is it to collect hair-whorl-direction data? Klar says that he, for one, got lucky: ‘By chance I happened to be vacationing at a beach where preponderance of gay men was fortuitously noticed. The subjects were considered to be homosexuals because of their public display of stereotypical interpersonal relationship deemed typical of homosexual men. This assessment was reinforced by the dearth of females and children on the beach … Conveniently, the gay men were highly concentrated in one area of the beach. Such considerations made it relatively easy to collect the data on groups of predominantly gay men with great confidence even though the subjects were not asked for their sexual preference.’

A year later Klar returned to the same beach and collected another load of data. He reports: ‘Altogether in a combined sample of 272 mostly gay men observed, 29.8% exhibited counterclockwise hair-whorl orientation’. This, he says, is ‘vastly different from the value of 8.4% counterclockwise rotation found in the public at large, which included both males and females.’

Observed: ‘hair-whorl phenotype’. The author explains: ‘By holding the picture in front of a mirror and looking at its image, the reader can appreciate the counterclockwise orientation.’

The study does not take account of the erstwhile hair-whorl directionality of persons who are now bald. He explicitly excluded them from consideration, along with anyone who was wearing a sun hat.

Klar suggests a direction for further exploration: ‘It should be equally interesting to compare the proportions of clockwise and counterclockwise hair-whorl orientations in lesbian women with those in females at large.’

The report ends with a simple notice that deftly fends off the research-is-a-waste-of-government-money crowd: ‘Author’s personal funds were used for the study.’

Klar, Amar J. S. (2004). ‘Excess of Counterclockwise Scalp Hair-Whorl Rotation in Homosexual Men’. Journal of Genetics 83 (3): 251–5.

Research spotlight

‘Digit Ratio (2D:4D) in Lithuania Once and Now: Testing for Sex Differences, Relations with Eye and Hair Color, and a Possible Secular Change’

by Martin A. Voracek, Albinas Bagdonas, and Stefan G. Dressler (published in Collegium Antropologicum, 2007)

Experiments with nude dolls

A generic life-size doll, with no modifications, was the key element in at least one unplanned experiment – the experiment documented in a 1993 letter to the journal Genitourinary Medicine entitled ‘Transmission of Gonorrhoea through an Inflatable Doll’. But, generally, scientists who conduct planned experiments that rely on life-size dolls prefer to carefully optimize, or even create, their own doll.

That unplanned inflatable doll experiment centred on a ship’s captain who ‘with some hesitation … told the story’ while being treated at a sexual disease clinic in Greenland. The captain had without permission entered an absent crewman’s cabin, borrowed a piece of equipment and later suffered the consequences.

That inflatable doll was not purpose-built for scientific use. Only through delightful happenstance did it satisfy the scientists’, as well as the captain’s, needs. Most scientists hate to depend on serendipity, especially if they have to depend on a doll.

A study called ‘Convective Heat Transfer from a Nude Body Under Calm Conditions: Assessment of the Effects of Walking With a Thermal Manikin’ exhibits the forethought and niggling care that can go into acquiring a suitable nude doll. Five mechanical engineers at the University of Coimbra, Portugal, wanted to study how, as a person strolls in the open air, heat flows both away from and into the skin. So, they obtained ‘a Pernille type thermal mannequin named Maria’, which ‘is articulated and divided into 16 parts independently controlled by a computer’. Maria features ‘a fibreglass armed polyester shell covered with a thin nickel wire wound around all the body to ensure heating and temperature measurement’.

In 2004, an entire, special issue of the European Journal of Applied Physiology featured twenty-seven studies involving mannequins. In some of those studies, the researchers refer to their mannequin by name. Jintu Fan and Xiaoming Qian, of Hong Kong Polytechnic University’s institute of textiles and clothing, called their monograph ‘New Functions and Applications of Walter, the Sweating Fabric Manikin’.

Fan and Qian write that Walter ‘simulates perspiration using a waterproof, but moisture-permeable, fabric “skin” [that] can be unzipped and interchanged with different versions to simulate different rates of perspiration’. Fan and Qian say their greatest challenge about Walter ‘is to measure the amount of water added to or lost from [him].’

‘Walter in “walking motion” ’

In other experimental studies, ones where a mannequin is subjected to hellacious treatment, the writing sometimes shows a particular, uncomfortable kind of restraint. ‘Exposure to hot water steam is a potential risk in the French Navy’, says one such paper, explaining a moment later that ‘this extreme environment during an accident leads to death in a short time’. In that study, as in others involving extreme exposures, the mannequin’s name – if anyone bothered even to give it a name – is withheld from the public.

Ellen Kleist and Harald Moi were honoured with the 1996 Ig Nobel Prize in public health for the doll ghonorrhoea report.

Kleist, Ellen, and Harald Moi (1993). ‘Transmission of Gonorrhoea through an Inflatable Doll’. Genitourinary Medicine 69 (4): 322.

Virgílio, A., M. Oliveira, Adélio R. Gaspar, Sara C. Francisco and Divo A. Quintela (2012). ‘Convective Heat Transfer From a Nude Body Under Calm Conditions: Assessment of the Effects of Walking With a Thermal Manikin’. International Journal of Biometeorology 56 (2): 319–32.

Fan, Jintu, and Xiaoming Qian (2004). ‘New Functions and Applications of Walter, the Sweating Fabric Manikin’. European Journal of Applied Physiology 92 (6): 641–4.

Desruelle, Anne-Virginie, and Bruno Schmid, ‘The Steam Laboratory of the Institut de Médecine Navale du Service de Santé des Armées: A Set of Tools in the Service of the French Navy’. European Journal of Applied Physiology 92 (6): 630–5.

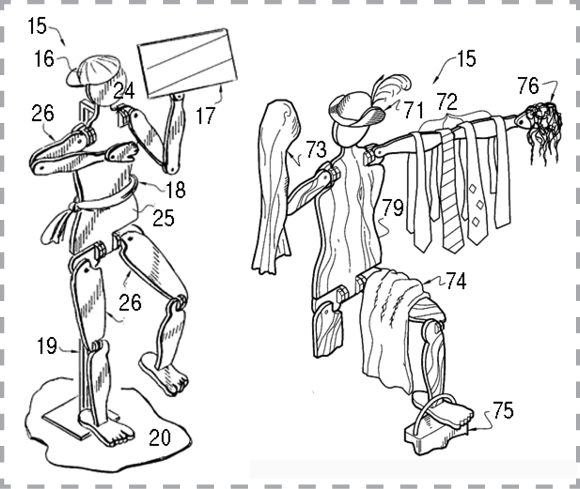

An improbable innovation

‘Human-figure display system’

a/k/a mannequin with repositionable arms and legs, by Rebecca J. Bublitz and Annette L. Terhorst (US patent no. 6,601,326, granted 2003)

Figures 1 and 8 from US patent no. 6,601,326.

Slime to the rescue

Slime would become the US military’s prime weapon to immobilize large ships under a scheme outlined for the US Air Force’s Air Command and Staff College.

Lieutenant Commander Daniel Whitehurst, a student at the college, figured out how to combine a raft of existing technologies to produce the officially ‘non-lethal’ armament he calls The Slimeball. He prepared a report in 2009. ‘The Slimeball’, Whitehurst writes, ‘is a two-part weapon system consisting of a floating sticky foam barrier that will resist attempts to remove it, and a submerged gel barrier that will impede movement through a ship channel. The parts can also be used independently of each other.’

Whitehurst gives three examples of targets well suited for The Slimeball’s gooey power. He explains how to use it against pirates in Boossaaso, Somalia; against the Iranian navy near the city of Bandar Abbas in the Strait of Hormuz; and against China’s underground submarine base at Sanya, on Hainan Island.

The Slimeball requires foam with particular qualities. Whitehurst specifies: ‘The primary component of such a material would contain properties commonly found in shaving cream … As commercially formulated, shaving cream is too insubstantial to create more than a nuisance to vessels, but in a denser form and combined with the chemical properties like those of a pre-existing substance known in defence circles as “sticky foam”, it would pose a far greater challenge for removal and have a greater dissuasive effect on vessels operating on the surface.’

Sticky foam, Whitehurst explains, was designed for use against people. He allows that it has ‘some significant drawbacks’ as an anti-personnel weapon. These include ‘the risk of suffocation and the inability to transport the target due to the, well, stickiness of the material’.

Whitehurst expresses optimism that this kind of officially non-lethal tool need not be lethal. ‘It has been suggested that due to the maturity of knowledge and development in this field, the drawbacks can be “engineered out” ’, he writes.

Detail from ‘Report Documentation Page’

The US Air Force has a history of imaginative weaponry proposals. Whitehurst says ‘many attempts have been made over the years to impede naval forces in a variety of manners, including floating smoke pots, entanglement devices, and even “floating purple mountains of shaving cream” … but none ever made it into wide use.’

More flashily, plans prepared long ago at the US Air Force’s Wright laboratory, in Dayton, Ohio, called for development of a potent chemical weapon. This is the so-called gay bomb that makes enemy soldiers sexually irresistible to each other. Wright laboratory was awarded the Ig Nobel peace prize in 2007 for instigating that line of research.

Whitehurst, Daniel L. (2009). ‘The Slimeball: The Development of Broad-scale Maritime Non-lethal Weaponry’. Research report submitted in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements, Air Command and Staff College, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, April.

n.a. (1994). ‘Harassing, Annoying, and “Bad Guy” Identifying Chemicals’. Wright Laboratory, WL/FIVR, Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio, 1 June.

And his hair turned white …

In a study called ‘Sudden Whitening of the Hair: An Historical Fiction?’, Anne-Marie Skellett, George Millington and Nick Levell, at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, try to chop off a myth at its roots. People’s hair, they believe, does not all of a sudden turn white. It just doesn’t. Goodbye, ye hoary tales of Queen Marie Antoinette of France and Sir Thomas More of England each turning whitehaired the night before being beheaded.

Hair whitening – ‘canities’ in medical lingo – takes longer than days or even weeks, they report in a 2008 issue of the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. If somebody’s hair did suddenly turn white, they say, it would most likely have an unnatural cause: ‘the washing out, or lack of access to a temporary hair dye’.

They suggest one other possible, though maybe nonexistent, mechanism. The disease alopecia totalis makes people’s hair fall out. Perhaps, in someone of mixed white and dark hair, some rare form of the disease might make only the dark strands fall out.

In medical monographs over the past one hundred years, doctors have almost uniformly expressed scepticism. In 1972, Josef Jelinek, of New York University medical school, debunked dozens of supposedly documented sudden-hair-whitening claims with a monograph in the Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine.

Jelinek, an MD, began by directing the blame: ‘It was not the physician but rather the historian who first seized on stories of sudden whitening to dramatize the tribulations of famous persons, principally in their grief or fear, in order to interest and astonish the reader. The poet, too, found poignancy in this phenomenon.’ He mentions as an example Shakespeare’s King Henry IV, Part 1, where Falstaff says to Hotspur: ‘Worcester is stolen away tonight. Thy father’s beard is turned white with the news.’

Dr Alexander Navarini and Dr Ralph Trüeb at University Hospital of Zürich, Switzerland, have become the foremost modern scholars of sudden-whitening. In 2009, they published a report called ‘Marie Antoinette Syndrome’, about a fifty-four-year-old woman whose ‘entire scalp hair suddenly turned white within a few weeks’. The next year, they published a paper called ‘Thomas More Syndrome’, about a fifty-six-year-old man ‘with sudden total whitening of scalp hair and eyebrows within weeks’.

They potter on about the names: ‘Saint Thomas More, who turned white in 1535, ought to have the right of seniority over the Queen of France who succumbed to the same fate in 1793. Since there seems to be no other particular reason for favouring Marie Antoinette over Thomas More, out of fairness, it would seem appropriate to use the term “Marie Antoinette syndrome” for the condition afflicting women and “Thomas More syndrome” for men.’ They further contributed to our knowledge of saints’ hair with a 2010 paper called ‘Beneath the Nimbus’.

Some saints summarized by hirsuteness, from ‘Beneath the Nimbus’

Navarini and Trüeb also disseminated some dark, happy hair news. In a monograph called ‘Reversal Of Canities’ they explain that they can’t really explain why a sixty-seven-year-old ‘otherwise healthy’ man ‘presented with spontaneous repigmentation of his grey hair’.

Skellett, Anne-Marie, George W.M. Millington and Nick J. Levell (2008). ‘Sudden Whitening of the Hair: An Historical Fiction?’. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 101( 12): 574–6.

n.a. (1910). ‘Sudden Whitening of the Hair’. The Lancet 175 (4525): 1430–1.

n.a. (1973). ‘Sudden Whitening of the Hair’. British Medical Journal 1 (5852): 504.

Jelinek, Joseph E. (1972). ‘Sudden Whitening of the Hair’. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 48 (8): 1003–13.

Navarini, Alexander A., Stephan Nobbe and Ralph M. Trüeb (2009). ‘Marie Antoinette Syndrome’. Archives of Dermatology 145 (6): 656.

Trüeb, Ralph M., and Alexander A. Navarini (2010). ‘Thomas More Syndrome’. Dermatology 220: 55–6.

Navarini, Alexander A., and Ralph M. Trüeb (2010). ‘Why Henry III of Navarre’s Hair Probably did Not Turn White Overnight’. International Journal of Trichology 2 (1): 2–4.

— (2010). ‘Reversal of Canities’. Archives of Dermatology 146 (1): 103–4.

Trüeb, Ralph M., and Alexander A. Navarini (2010). ‘Beneath the Nimbus: The Hair of the Saints’. Archives of Dermatology 146 (7): 764.

In brief

‘Why the Long Face?: The Mechanics of Mandibular Symphysis Proportions in Crocodiles’

by Christopher W. Walmsley, Peter D. Smits, Michelle R. Quayle, Matthew R. McCurry, Heather S. Richards, Christopher C. Oldfield, Stephen Wroe, Phillip D. Clausen and Colin R. McHenry (published in PLos ONE, 2013)

‘Bite, shake and twist’ pressure points of three crocodile species

Greek cheek

How many Greek children have dimpled cheeks? Until recently no one really knew, but now there is detailed information as to exactly how many do, how many don’t, and where the dimples are.

Athena Pentzos-DaPonte of Aristotle University in Thessaloniki and an international team counted the dimples on 14,141 male and 14,141 female Greek children and adolescents. To be thorough, they observed the children smiling and also not smiling.

The scientists performed this count in 1980. A quarter century later, they finished their quantitative analysis of the data, and published a report in the International Journal of Anthropology. The report does not explain the significance, if any, of the number 14,141.

The data paint a clear picture. Approximately 13 percent of Greek children had a noticeable cheek dimple or dimples. Girls and boys were almost equally well dimpled.

Pentzos-DaPonte and her colleagues – Alessandro Vienna from the University of Rome, Larry Brant from the National Institute on Aging in Baltimore, Maryland, and Gertrude Hauser from the University of Vienna – also considered location. Was a dimple on the left? Was it on the right? Or (to put it in technical terms) was the dimpling bilateral? Left-dimpled Greek children were as common as right-dimpled, but only about 3.5 percent of youngsters had dimples in both cheeks.

In 1983 Pentzos-DaPonte and colleague Silke Grefen-Peter published a study of cheek dimpling in Greek adults. About 34 percent of the adults had dimples – almost triple the occurrence of dimpling in Greek youths. The scientists now speculate that most of those adult dimples are literally old-fashioned: the skin aged, lost elasticity and gained sag.

Greece has always been a nation that prizes knowledge. Few other countries, though, know the prevalence of cheek dimpling among any age group. It would seem a straightforward procedure to count dimples. But, increasingly, such figures are becoming subject to manipulation.

For example, Dr Pichet Rodchareon, of the Pichet Plastic Surgery Clinic in Bangkok, Thailand, advertises his willingness to insert cheek dimples for a cost (as I am writing this) of US $1500 per dimple. Rodchareon is one of the most prominent advertisers of this particular service (and other services too; his website says the practice is ‘The Leading Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Center of Cosmetic Surgery and Sex Change Surgery in Bangkok, Thailand’), but many plastic surgeons have the skill and experience to sculpt a dimple. Some even offer a reversible cheek dimple operation.

At the 2002 World Congress of Cosmetic Surgery, held in Shanghai, China, Dr Xuan Cuong Nguyen of Vietnam presented a talk called ‘An Easy and Precise Way to Make a Cheek Dimple’. This is the same Dr Nguyen who just the year before was awarded the ‘World Leader of Cosmetic Surgery’ gold cup at a ceremony in Mumbai, India. So far, his method has not proved as easy as it sounds, given that the price of artificial cheek dimples has not yet tumbled. That’s unhappy news for the dimple seeker on a tight budget.

Pentzos-DaPonte, Athena, Alessandro Vienna, Larry Brant and Gertrude Hanser (2004). ‘Cheek Dimples in Greek Children and Adolescents’. International Journal of Anthropology 19 (4): 289–95.

Pentzos-Daponte, Athena (1986). ‘4 Anthroposcopic Markers in the Northern Greece Population: Hand Folding, Arm Folding, Tongue Rolling and Tongue Folding’. Anthropologischer Anzeiger 44 (1): 55–60.

May we recommend

‘The Treatment Dilemma Caused by Lumps in Surfers’ Chins’

by Jun Fujimura, Kenji Sasaki, Tsukasa Isago, Yasukimi Suzuki, Nobuo Isono, Masaki Takeuchi and Motohiro Nozaki (published in Annals of Plastic Surgery, 2007)

Hair-raising treats

Alexander Tse-Yan Lee – or, as he generally identifies himself: Alexander Tse-Yan Lee, BH Sci., Dip. Prof. Counsel., MAIPC, MACA – was in the news some years ago, albeit tangentially. For a while the Internet was slightly a-twitter (though not via Twitter, which did not yet exist) with mentions of Lee’s piece of writing entitled ‘Hair Soy Sauce: A Revolting Alternative to the Conventional’. It appeared in the Internet Journal of Toxicology, adding to that publication’s stock of grim, occasionally grimy delights. The article’s section headings do a good job of both stoking and satisfying the reader’s interest:

- The Soy Sauce – An Introduction

- The Cheap Soy Sauce That Aroused the Public

- The Stunning Alternative to Soy – the Human Hair

- Toxic Consequences of The Hair and The Chemicals

- The Boycott Phenomena

- Conclusion

Little attention has been paid to Dr Lee himself, or to his other work.

Lee’s stated affiliation is unusual: Queers Network Research of Hong Kong, China. So are his other published papers, several of which also appear in the Internet Journal of Toxicology.

‘The Foods From Hell: Food Colouring’, is filled with colourfully tasty details. It, too, reveals its gist to the reader who skims the section titles:

- Food Colouring Agents: Synthetic Versus Natural

- Coloured Chinese Steamed Corn-Buns

- Coloured Dry Shrimps (Dried Shrimps?)

- Coloured Fruits

- Coloured Vegetables

- Coloured Dark Rice

- Coloured Traditional Chinese Herbal Medicinal Products

- Conclusion

Lee’s biography mentions a study called ‘It Is Foods that Look Good Kill You’, which is described as being ‘in press’ in the Internet Journal of Toxicology. It is not clear, if one goes looking for the report itself, whether ‘It Is Foods that Look Good Kill You’ was an early title that was later published, to little acclaim, as ‘The Foods From Hell’, or whether it has yet to appear.

Lee did publish ‘Faked Eggs: The World’s Most Unbelievable Invention’. It, too, features tiny, tale-telling section titles that, in another setting, might comprise an entire short poem:

- A Brief Introduction to Problem Foods in Mainland China

- The Eggs that Cause Problems

- The ‘Red Yolk’ Eggs

- The Soil-Filled Eggs

- The Human-Made Eggs

- Is it a good advice to sniff the eggs only?

- Conclusion

Earlier, Dr Lee wrote a book called My Weight Loss Diary eBook, which foreshadows many of his later works. He offered it on the Internet. The summary alone may be worth the $6 price: ‘With certificate from a pancake challenge after finishing a stack of pancake in less than 2 minutes; holding a record of eating 8 family size pizzas in a buffet dinner; having two burgers with milk shake for lunch everyday and finishing an extra large size frozen chicken with chips and gravy for snacks while still demanding for more.’

Some of the articles disappeared from the Internet, having lived quiet lives that persist in the memories of people who voraciously consume all news about hair, soy sauce or faked eggs – and persist also, of course, in the mind of Alexander Tse-Yan Lee, BH Sci., Dip. Prof. Counsel., MAIPC, MACA.

Lee, Alexander Tse-Yan (2005). ‘Hair Soy Sauce: A Revolting Alternative to the Conventional’. Internet Journal of Toxicology 2 (1): n.p.

— (2005). ‘The Foods From Hell: Food Colouring’. Internet Journal of Toxicology 2 (2): n.p.

— (in press). ‘It Is Foods that Look Good Kill You’. Internet Journal of Toxicology.

— (2005). ‘Faked Eggs: The World’s Most Unbelievable Invention’. Internet Journal of Toxicology 2 (1): n.p.