Six

Navel Gazing, Curious Consuming

In brief

‘Biting Off More Than You Can Chew: A Forensic Case Report’

by J.R. Drummond and G.S. McKay (published in the British Dental Journal, 1999)

Some of what’s in this chapter: Query your belly • Synchronize your cows • Know thy fly • Colour-change thy cereal • Drink in your results • Meet your meat, in unintended circumstances • Peruse your hot potatoes • Disgust your carnivore shrink • Define your vegetarian, strictly • Weigh your falafel • Identify your water • Sneak-peek your hosts’ food • Slim up your fatter fellows • Chew your crisp cereal • Cereal-flake your cows • Scrawl your boozy scrawl • Note your neighbours in the pub

Exposing the German beer belly

A team of scientists has attacked the idea that beer is the main cause of beer bellies in Germans. As with many biomedical questions, an absolute, indisputable answer may be impossible. To obtain it would require continuously monitoring and measuring, over a span of years, every sip and morsel drunk and eaten by a vast number of people.

The only practical method involves asking beer-drinkers to dig deep into their memory and estimate or take a wild guess as to their typical intake of beer and everything else that has passed down their gullet.

Madlen Schütze and other researchers at the German Institute of Human Nutrition Potsdam-Rehbrücke and at Fulda University of Applied Sciences, together with a colleague at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, gave it their best shot in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

The team analysed 19,941 men and women’s weight, waist measurements and hip circumference over four years. The researchers asked participants to fill out a survey on their beer consumption.

The participants gave an estimate, with whatever degree of accuracy they were able or willing to supply, of how much they had been imbibing daily. Their estimates were based on the size of a typical bottle of beer in Germany.

The researchers classified men’s consumption differently to women’s. Women were placed in four categories from ‘no beer’ to ‘moderate drinkers’. Men were put in five categories from ‘no beer’ to ‘heavy drinkers’. For women, ‘moderate’ meant consuming at least 250 millilitres of beer a day. For men, ‘moderate’ meant 500 to 1,000 millilitres a day.

The team conclude that their study ‘does not support the common belief of a site-specific effect of beer on the abdomen, the beer belly’. ‘Beer consumption’, they write, ‘seems to be rather associated with an increase in overall body fatness’.

A study in the Czech Republic, published several years earlier in the same medical journal, balks at the idea that drinking beer by itself causes much change in weight, let alone waistlines, in Czechs. The study aimed to investigate the ‘common notion that beer drinkers are, on average, more “obese” than either nondrinkers or drinkers of wine or spirits’. Schütze and colleagues argue that that Czech study was probably flawed, that its findings were a bit bloated.

One can quibble about the definition of a beer belly, but the German researchers say that, for their purposes, a beer belly is a ‘site-specific effect’. A beer belly, they argue, is a belly that bulges distinctly at the waist. It contrasts, in a big way, with whatever mass and expanse may adjoin it above or below that region.

Schütze, Madlen, Mandy Schulz, Annika Steffen, Manuela M. Bergmann, Anja Kroke, Lauren Lissner and Heiner Boeing (2009). ‘Beer Consumption and the ‘Beer Belly’: Scientific Basis or Common Belief?’. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 63 (9): 1143–9.

Bobak, Martin, Zdenka Skodova and Michael Marmot, (2003).‘Beer and Obesity: A Cross-sectional Study’. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57 (10): 1250–3.

Synchronized cows

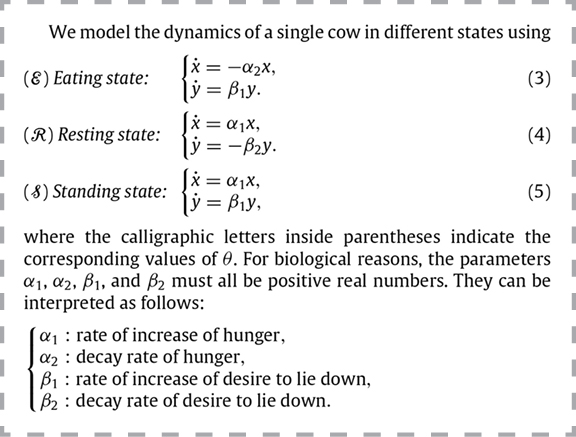

A British-American team of scientists has produced a study called ‘A Mathematical Model for the Dynamics and Synchronization of Cows’. They were driven partly by the intellectual challenge, and at least a little by an EU council directive (precisely, council directive 97/2/EC), which mandates ‘that cattle housed in groups should be given sufficient space so that they can all lie down simultaneously’.

Their key insight, the team says, was to realize ‘it is biologically plausible to view [cattle] as oscillators … During the first stage (standing/feeding), they stand up to graze but they strongly prefer to lie down and “ruminate” or chew the cud for the second stage (lying/ruminating). They thus oscillate between two stages.’

The researchers ‘modeled the eating, lying, and standing dynamics of a cow using a piecewise linear dynamical system … We chose a form of coupling based on cows having an increased desire to eat if they notice another cow eating and an increased desire to lie down if they notice another cow lying down.’ This, they say, led to at least one unexpected discovery: ‘[We] showed that it is possible for cows to synchronize less when the coupling is increased.’

The researchers – Mason Porter and Marian Dawkins at Oxford University, and Jie Sun and Erik Bollt at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York – published their work in the physics journal Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. In the thirty-one-year history of that journal, this was the first article specifically about cows. (Cows do have an accepted, very humble place in the history of physics: an old joke, beloved by physicists and a few others. The joke starts [usually] with a physicist offering to solve a dairy-related problem for a desperate farmer. The physicist walks to a blackboard, and draws a circle. ‘First’, he says, ‘we assume a spherical cow …’).

Decoding a cow’s hunger versus its desire to lie down, mathematically

The team built upon the work of earlier, fully serious bovi-mathematical scholars.

In 1982, P.F.J. Benham of Reading University published an innovative study called ‘Synchronization of Behaviour in Grazing Cattle’. Brennan studied a herd of thirty-one Friesian cows, recording the behaviour of each every five minutes during daylight for fifteen days. His short paper – it’s only two pages long – ends with the declaration: ‘Studies of behaviour synchronization are evidently relevant to the management of grazing cattle.’

Porter, Dawkins, Sun and Bollt also looked beyond the bounds of cow analysis, gaining insight from a 1991 monograph by A.J. Rook and P.D. Penning of the AFRC Institute of Grassland and Environmental Research in Hurley, Maidenhead. Rook and Penning called their report ‘Synchronisation of Eating, Ruminating and Idling Activity by Grazing Sheep’, and published it in the journal Applied Animal Behaviour Science. They reached four conclusions. I will mention only one, as it has wide applicability: ‘Start of meals was more synchronised than end of meals.’

Sun, Jie, Erik M. Bollt, Mason A. Porter and Marian S. Dawkins (2011). ‘A Mathematical Model for the Dynamics and Synchronization of Cows’. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 240: 1497–1509.

Benham, P.F.J. (1982). ‘Synchronization of Behaviour in Grazing Cattle’. Applied Animal Ethology 8 (4): 403–4.

Rook, A.J., and P.D. Penning (1991). ‘Synchronisation of Eating, Ruminating and Idling Activity by Grazing Sheep’. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 32 (2/3): 157–66.

To know a fly

Vincent Dethier loved flies with a fervour that is rare. He distilled this love into a book called To Know a Fly.

Page fifty-three tells what happens when Dethier severed the tiny nerve that tells a fly whether it has had enough to eat: ‘The results of this operation on a hungry fly were spectacular. Such a fly began to eat in the normal fashion, but did it stop? Never. It ate and ate and ate. It grew larger and larger. Its abdomen became so stretched that all the organs were flattened against the sides. It became so big and round and transparent that it could almost be used as a miniature hand lens. It was so round its feet no longer reached the ground and so heavy it could not launch itself into the air. Even though the back pressure from a near bursting crop was terrific, the fly continued in its attempts to eat. It reminded me of a woman who had been admitted to our hospital, a woman whose height was four feet, ten inches and whose weight approached four hundred pounds. Her major complaint was inability to move.’

In just 119 pages Dethier describes many of the fly’s unadvertised charms and wonders. He makes no pretence of giving explanations for particular wonders that neither he nor any other scientist really understands. This in itself is wonderful and charming. Consider: ‘We know … there is a time when the female fly prefers protein, which cannot nourish her own body, to sugar, which is an adequate food for her but useless for her eggs. Here is an example of survival of the individual being subordinated to survival of the species. In some quarters it would be hailed as maternal instinct, and by so naming it we would be no nearer an understanding of what it is.’

Dethier hungered still for information about flies, producing many detailed studies, including a 489-page book, The Hungry Fly, in 1976.

To Know a Fly first appeared in 1962. Dethier was a biologist based at Princeton and, at various times, at other universities. There is poetry in his book, but not the lugubrious kind that makes practical people flee. Many chapters begin with brief passages from Don Marquis’s 1927 book Archy and Mehitabel, which is the source of much modern wisdom about cockroaches and cats (and perhaps about people, too). Had Dethier’s book appeared first, it would not have been out of place as source of chapter lead-in material for Marquis and Archy.

I learned about To Know a Fly from Shelly Marino of Cornell University, who described it as ‘the book that turned me into a biologist in the first place’. This book can do for flies what the Harry Potter films have done for Daniel Radcliffe and Emma Watson. It is magically powerful stuff.

Dethier, Vincent G. (1962). To Know a Fly. San Francisco: Holden-Day.

— (1976). The Hungry Fly: A Physiological Study of the Behavior Associated with Feeding. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Marquis, Don (1927). Archy and Mehitabel. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page.

In brief

‘Specialist Ant-eating Spiders Selectively Feed on Different Body Parts to Balance Nutrient Intake’

by S. Pekár, D. Mayntz, T. Ribeiro and M.E. Herberstein (published in Animal Behaviour, 2010)

Chameleon crunch

When parents warn children not to play with their food, there’s now reason to add a menacing ‘even if’: ‘even if the food begins playing with you’. Recently, food was given a new ability to play, a little, the moment it encounters milk.

Researchers have patented a way to make breakfast cereal change colour as it sits in the bowl, awaiting its roller-coaster ride down somebody’s throat.

The patent documents explain why the world needs this to occur, as well as how, chemically and mechanically, to do it.

Hideo Tomomatsu of Crystal Lake, Illinois, filed a patent application in 1987 for what he called ‘colour-changing cereals’. Eight years later, Joseph Farinella of Chicago, Illinois, and Justin French of Cedars, Iowa, used much of the same stilted wording in filing their own application. Both patents were granted, with the rights being assigned to the Quaker Oats Company. Quaker’s colour-changing was in ‘Cap’n Crunch’ cereal – expressly, the ‘Polar Crunch’ variety, which apparently was on sale as early as 2006.

Particular coating compositions tested. The inventors note: ‘While the invention has been described with respect to certain preferred embodiments, as will be appreciated by those skilled in the art, it is to be understood that the invention is capable of numerous changes, modifications and rearrangements’ which, they say, ‘are intended to be covered’ by the patent.

The Quaker Oats Company, founded in 1901, makes breakfast cereal – buckets and buckets of it. Playing with food is good for its industry. Quaker even partially financed the apotheosis of that activity: the 1971 film version of Roald Dahl’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

The patent language puts the new, shade-shifting food in context: ‘One approach to engage the interest of children, as well as other people, in eating RTE [Ready to Eat] cereal would be an RTE cereal that changes colour on contact with an aqueous edible medium such as cold milk, hot water, etc. To make the change more interesting, the colour change should be rapid and substantial.’

‘There is a need’ for this, the inventors write.

‘There is also a need’, they continue, ‘for a method for making colour-changing cereals that is efficient and cost-effective.’

Their method is to create cereal pieces of one colour, then coat them with powder of a different hue. That leads to breakfast table magic: ‘The coating is of a second colour different from the first colour and is in a quantity sufficient to obscure the first colour … Upon mixing milk with the resulting cereal, the edible powdered surface is instantly dissolved or dispersed, revealing the specific colours of the individual pieces very quickly.’

What are the ingredients? Glad you asked. ‘The cereal base has a coating comprising cornstarch, powdered sugar, [and] food colouring.’

The researchers tinkered with the recipe, to see how quickly they could make the cereal disrobe. That resulted in what they believe to be a scientific discovery: ‘Surprisingly, the use of cornstarch in the correct ratio to powdered sugar increases the speed of the colour change. This creates a more startling effect that is appealing to children.’

That ratio, with a cereal coating of mostly starch and just a smidge of sugar, got the transformation down to a presto-change-o, what-a-way-to-start-the-day seven seconds.

Tomomatsu, Hideo (1989). ‘Color-changing Cereals and Confections’. US patent no. 4,853,235, 1 August.

Farinella, Joseph R., and Justin A. French (2010). ‘Color-changing Cereal and Method’. US patent no. 7,648,722, 19 January.

Drinking in the results

America, a rich source of alcohol, of alcoholics, and of aggressive alcoholics, is also rich in scholarship on those subjects. One must drink deep of that scholarship, in many cases, if one cares about the question: what, exactly, did some of those researchers hope to learn by doing that research? The flow of prose produced by these researchers could drown anyone who tried to ingest more than occasional, measured amounts of it.

In a 1999 study called ‘The Effects of a Cumulative Alcohol Dosing Procedure on Laboratory Aggression in Women and Men’, Donald Dougherty and colleagues at the University of Texas-Houston medical school report making several discoveries: (1) Both men and women became more aggressive after they drank alcohol; (2) those men and women became even more aggressive ‘after consuming the second alcoholic drink’; (3) their aggressiveness ‘remained elevated for several hours’ after they finished drinking; and (4) the individuals who were most aggressive when sober were also the most aggressive when drunk.

Three years later, Peter Giancola at the University of Kentucky wrote a study called ‘Irritability, Acute Alcohol Consumption and Aggressive Behaviour in Men and Women’. ‘The finding of greatest importance’, Giancola says, ‘was that alcohol increased aggression for persons with higher, as opposed to lower, levels of irritability.’

The following year, Dominic J. Parrott, Amos Zeichner and Dana Stephens at the University of Georgia published a treatise called ‘Effects of Alcohol, Personality, and Provocation on the Expression of Anger in Men: A Facial Coding Analysis’. Parrott and his colleagues experimented, and made two big discoveries. First: that drunken people made ‘facial expressions of anger’ more often than sober people. Second: that when highly provoked, drunks also showed a general ‘tendency to express anger outwardly’.

Many other alcohol mysteries are explained in these same research journals. In 1995, Siegfried Streufert and fellow researchers at Penn State boozed up some managers. Streufert published a study, called ‘Alcohol Hangover and Managerial Effectiveness’. It reports that managers who drank moderately of an evening had perfectly adequate ‘complex decision-making competence’ the next morning.

Suzanne Thomas, Carrie Randall and Maureen Carrigan at the Medical University of South Carolina wrote a paper in 2003, called ‘Drinking to Cope in Socially Anxious Individuals: A Controlled Study’. They explain: ‘The results of this study confirm earlier observations that individuals high in social anxiety deliberately drink to cope with social fears’.

In 2005, Soyeon Shim at the University of Arizona and Jennifer Maggs at Penn State University went looking for results. They found some. Their study called ‘A Cognitive and Behavioral Hierarchical Decision-making Model of College Students’ Alcohol Consumption’ says: ‘Results indicated that personal values can serve as significant predictors of the attitudes college students have toward alcohol use, which in turn can predict intentions to drink. Results also indicated that intentions to drink are strongly related to actual alcohol consumption’.

Dougherty, Donald M., James M. Bjork, Robert H. Bennett and F. Gerard Moeller (1999). ‘The Effects of a Cumulative Alcohol Dosing Procedure on Laboratory Aggression in Women and Men’. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 60 (3): 322–9.

Giancola, Peter R. (2002). ‘Irritability, Acute Alcohol Consumption and Aggressive Behavior in Men and Women’. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 68 (3): 263–74.

Parrott, Dominic J., Amos Zeichner, and Dana Stephens (2003). ‘Effects of Alcohol, Personality, and Provocation on the Expression of Anger in Men: A Facial Coding Analysis’. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 27 (6): 937–45.

Streufert, Siegfried, Rosanne Pogash, Daniela Braig, Dennis Gingrich, Anne Kantner, Richard Landis, Lisa Lonardi, John Roache and Walter Severs (1995). ‘Alcohol Hangover and Managerial Effectiveness’. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 19 (5): 1141–6.

Thomas, Suzanne E., Carrie L. Randall, and Maureen H. Carrigan (2003). ‘Drinking to Cope in Socially Anxious Individuals: A Controlled Study’. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 27 (12): 1937–43.

Shim, Soyeon, and Jennifer Maggs (2005). ‘A Cognitive and Behavioral Hierarchical Decision-making Model of College Students, Alcohol Consumption’. Psychology and Marketing 22 (8): 649–68.

Research spotlight

‘An Ode to Substance Use(r) Intervention Failure(s): SUIF’

by Shlomo Stan Einstein (published in Substance Use and Misuse, 2012)

The vegetarian who ate a sausage with curry sauce

A report called ‘The Vegetarian Who Ate a Sausage with Curry Sauce’ can provide cheer both for meat-eaters – because it tells how a hunk of processed meat served as a helpful warning beacon, possibly lengthening a person’s life – and for vegetarians – because that meat was the stark symbol of someone’s health going very wrong.

Despite its children’s-bookish title, this report was published in the January 2003 issue of The Lancet Neurology, along with the less child-friendly sounding ‘Principles of Frontal Lobe Function’ and ‘Should I Medicate My Child?’.

The authors, Josef Heckmann, Christoph Lang, Hermann Stefan and Bernhard Neundörfer, of the department of neurology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg in Germany, tell the story of a sixty-one-year-old woman who visited her work canteen for lunch with a male colleague. ‘The colleague was greatly astonished to see the woman, a passionate vegetarian, order a sausage with curry sauce. Furthermore, during conversation, he noticed that she was a little confused, although she was able to walk and carry her tray without difficulty. Because of the woman’s changed behaviour, her colleague arranged a transfer to a hospital for her.’

Heckmann, Lang, Stefan and Neundörfer ran tests, and diagnosed this as a previously unsuspected case of non-convulsive status epilepticus, a form of epilepsy that can lead to coma and other bad states. They gave her medicine to prevent further seizures.

When a sausage induces a visit to hospital, most commonly it is food poisoning that drives the action. But occasionally, the cause and effect are mechanical. A sausage can get stuck on the journey from mouth to stomach, and sometimes does.

Such a case was reported in 2001 at James Paget hospital in Great Yarmouth. As reported by O.N. Enwo and M. Wright in the International Journal of Clinical Practice, under the headline ‘Sausage Asphyxia’: ‘a case of supraglottic impaction of the larynx by a piece of sausage occurred in our hospital; the patient was semiconscious. It was managed successfully by a carefully timed laryngoscope blade being inserted into the mouth without the aid of sedative drugs’.

There is some tendency for these cases to occur, or at least to be written up when they occur, in Germany and Austria. One fairly typical report was published in the medical journal Medizinische Klinik in 2009 about a seventeen-year-old fellow in Regensburg, Germany, who had a Wiener sausage in his oesophagus.

Occasionally, the mechanical problem occurs elsewhere than in the digestive tract. Austria supplied a new, perfect amplifier for the old saying ‘you don’t want to know how the sausages are made’. The June 2006 issue of the journal Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift [the Central European Journal of Medicine] featured a photo-illustrated report, from the city of Linz, called ‘Finger Amputation by a Sausage Packing Machine’.

Heckmann, Josef, Christoph Lang, Hermann Stefan, and Bernhard Neundörfer (2003). ‘The Vegetarian Who Ate a Sausage with Curry Sauce’. Lancet Neurology 2 (1): 62.

Enwo, O.N., and M. Wright (2001). ‘Sausage Asphyxia’. International Journal of Clinical Practice 55 (10): 723–4.

Gäbele, Erwin, Esther Endlicher, Ina Zuber-Jerger, Wibke Uller, Fabian Eder and Jürgen Schölmerich (2009). ‘Impaction of a “Sausage Bread” in the Oesophagus: First Manifestation of an Eosinophilic Oesophagitis in a 17-Year-Old Patient’. Medizinische Klinik 104 (5): 386–91.

Huemer, Georg M., Harald Schoffl and Karin M. Dunst (2006). ‘Finger Amputation by a Sausage Packing Machine’. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 118 (11/12): 321.

May we recommend

‘Hot Potatoes in the Gray Literature’

by Brian Pon and Alan Meier (published as Recent Research in the Building Energy Analysis Group, 1993)

Mincing vegetarianism, not words

Vegetarianism – the wanton ingestion of nothing but non-meat – sometimes produces or provokes antipathy, hostility and disgust. Researchers have struggled to understand why. In 1945, as the Second World War was ending, US Army Major Hyman S. Barahal, chief of the psychiatry section of Mason General Hospital in Brentwood, New York, issued a report called ‘The Cruel Vegetarian’. Major Barahal began by explaining the word ‘vegetarianism’ for anyone who might be ignorant or confused: ‘It consists essentially in the exclusion of flesh, fowl and fish from the dietary.’

Major Barahal drew upon his own experience at having met, and endured the presence of, several vegetarians. ‘Their exaggerated concern over the welfare of animals betrays the utter contempt and hatred which they hold for the human race generally’, he reported. ‘As far as the present writer knows, no [previous] article has ever attempted to explain the psychology of a person who, of his own free will, becomes a fervent follower of the cult.’

Major Barahal preferred to mince vegetarians, rather then words. He cut directly to the meat of the matter: ‘The average vegetarian is eccentric, not only as regards his food, but in many other spheres as well. Careful observation of his views … will frequently reveal somewhat twisted and rather peculiar attitudes and prejudices. In short, the average vegetarian is not definitely “a lunatic”, but he certainly fringes on it.’ His report carries a footnote that says little but implies much: ‘This manuscript was prepared prior to the author’s entering military service and contains no material or conclusions gained from experiences in military service.’

Sixty years later, in 2005, Daniel Fessler of the University of California, Los Angeles, and three colleagues looked at the emotional tangle provoked in vegetarians by vegetarianism’s opposite number, meat eating.

Their treatise, called ‘Disgust Sensitivity and Meat Consumption: A Test of an Emotivist Account of Moral Vegetarianism’, appeared in the journal Appetite. It contrasts ‘moral vegetarians’, who ‘view meat avoidance as a moral imperative’, with ‘health vegetarians’, who ‘are upset by others’ meat consumption’. Fessler and his colleagues reached an emphatic conclusion: ‘moral vegetarians’ disgust reactions to meat are caused by, rather than causal of, their moral beliefs’.

The same year, 2005, the British Journal of Nutrition served up a French study called ‘Emotions Generated by Meat and Other Food Products in Women’, which includes a fairly rare occurrence of the phrase ‘low meat-eating women’: ‘As expected, the low meat-eating women felt more disappointment, indifference and less satisfaction towards meat than did the high meat-eating women. However, the low meat-eating women also stated other negative emotions such as doubt towards some starchy foods. The only foods that they liked more than high meat-eating women were pears and French beans.’

Researchers at the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, the Centre Européen des Sciences du Goût and the Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale et Cognitive collaborated in (1) collecting photographs of pears, apples, rice, pasta, pizza, pound cake, turkey, rabbit, pork chops, offal and other kinds of food; and (2) gathering sixty French women; and then (3) exposing the latter to the former. The women’s reactions to those photos led the researchers to a conclusion that perhaps did not surprise them: the failure to eat lots of meat is ‘associated with specific negative emotions regarding meat and other foods’.

Barahal, Hyman S. (1946). ‘The Cruel Vegetarian’. Psychiatric Quarterly 20 (1 supplement): 3–13.

Fessler, Daniel M.T., Alexander P. Arguello, Jeannette M. Mekdara and Ramon Macias (2003). ‘Disgust Sensitivity and Meat Consumption: A Test of an Emotivist Account of Moral Vegetarianism’. Appetite 41 (1): 31–41.

Rousset, S., V. Deiss, E. Juillard, P. Schlich and S. Droit-Volet (2005). ‘Emotions Generated by Meat and Other Food Products in Women’. British Journal of Nutrition 94 (4): 609–19.

Call for opinions

In the years since Major Barahal’s report on the psychology of vegetarians, questions have been raised about the definition of ‘vegetarianism’ used as a basis of his incisive analysis. One question in particular has caused agony for the Annals of Improbable Research scientific survey team.

The Question: Typically, strict vegetarians avoid eating meat, but consider anything else to be fair game (so to speak). Biologists classify most bacteria as being neither animal nor vegetable. If offered a good home-cooked meal of baked, stuffed bacteria, what’s a strict vegetarian to do? Are strict vegetarians allowed to eat bacteria?

The Results: An initial survey, conducted in 1999, chewed on the matter. Respondents’ answers ranged from ‘In a 5-kingdom classification system, vegetarians are allowed to consume 80% of living things’ to ‘Their GI tracts should be purged of their microfauna… Then see how healthy they are’. In summary, 32 percent of respondents allowed bacteria consumption and 32 percent did not, with 36 percent suggesting ‘other’ allowances.

Conclusions: Does this remain the state of this vego-bacterial matter? The Annals of Improbable Research team have been inspired by the January/February 2013 edition of the journal Gastrointestinal Cancer Research in which the editor-in-chief Daniel G. Haller issued ‘A Call for Opinions’. Haller opines: ‘Opinions from experts – however designated – remain important’ and ‘The worst ending to any editorial is “Further work needs to be done”.’ Further work needs to be done.

To propose your answer to the question, ‘Are strict vegetarians allowed to eat bacteria?’, please send by email:

- a photograph that clearly provides evidence of (1) your standing as a vegetarian, carnivore or omnivore; (2) a good home-cooked meal, noting whether it was digested with or without bacteria

- a current curriculum vita outlining your credentials as a scientist

- a pithy statement hashing out your opinion and rehashing your expert qualifications, both culinary and scholarly.

Send to marca@improbable.com with the subject line:

BACTERIA DIGEST SURVEY

Scrutinized falafel

A study called ‘Effect of a Popular Middle Eastern Food (Falafel) on Rat Liver’ is available to the public. Focusing strictly on the medical consequences (for rats) of eating ‘chickpeas paste seasoned with garlic, parsley, and special spices, then deep fried in vegetable oil’, it’s a ten-page journey from delight to despair, and finally to indifference.

Sana Janakat and Mohammad Al-Khateeb of the Jordan University of Science and Technology in Irbid, Jordan, wrote the report. It somewhat enlivens the February 2011 issue of the journal Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry.

Janakat and Al-Khateeb start with some cheery praise: ‘Falafel is considered the most popular fried food by all socio-economic classes in most Middle Eastern countries. It is consumed for breakfast, dinner, or as a snack. Among low-income families and labourers it is consumed on a daily basis, due to its availability, relatively low price, and good taste.’

Then come several pages of unhappy news that lead to a depressing and technical conclusion: ‘Long-term consumption of falafel patties caused a significant increase in ALP [alkaline phosphatase], ALT [alanine transaminase], bilirubin level and increased liver weight/body weight ratio … This indicates that consumption of large amounts of falafel on daily basis might lead to hepatotoxicity.’

But wait! That’s not the end of the story.

Here’s what Janakat and Al-Khateeb say they did.

First they gathered falafel: ‘Frying oil samples and falafel patties were collected from 20 restaurants located in different socio-economic neighbourhoods from the city of Irbid.’ They homogenized the falafel, soaked it for twenty-four hours, filtered it through cheesecloth and centrifuged it. This produced the experimental material – concentrated falafel – with which they performed two experiments.

An explanation of how and which falafel was collected

The first experiment assessed the short-term effect of eating falafel, short term in this case meaning five days. Janakat and Al-Khateeb extracted the oil from some falafel patties, and force-fed it to some rats for the whole five days. Then they killed those rats, and did post-mortems to get at the livers. The livers (happily, in a sense) looked in pretty good shape. Thus, the report says, the short-term effects of eating falafel are pretty benign.

The second experiment aimed to clarify the long-term effect of falafel consumption. A fresh batch of rats got to eat lots of falafel – as much as they pleased, whenever they wanted it – for a month. That was their entire diet: falafel, falafel, falafel. Then they were killed. Here, the post-mortem results were ugly. The study intones that ‘long-term consumption of falafel patties (30 days) caused yellowish discoloration of the liver distinctive of liver necrosis’, suggesting that ‘the consumption of falafel as the sole source of nutrition for a long period of time … can generate a hepatotoxic effect leading to liver necrosis’.

That may sound like bad news, but apparently it’s not. The very next sentence – nearly the last thing said in the report – is this: ‘Falafel consumption in moderation and in conjunction with other food items or beverages containing high antioxidant levels can be considered as safe.’

Janakat, Sana M., and Mohammad A. Al-Khateeb (2011). ‘Effect of a Popular Middle Eastern Food (Falafel) on Rat Liver’. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry 93 (2): 360–9.

Water tastes like water

Can people perceive the difference between bottled water and tap water? Two studies suggest that – at least in France and in Northern Ireland – water tastes like water.

A French research team ran a taste test of six different bottled mineral waters and six municipal tap waters. This was a collaboration between two scientific institutes (CNRS, the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and INRA, the National Institute of Agronomic Research) and Lyonnaise des Eaux, a company that manages many public water supplies.

The tasters were ‘389 persons from all over France’. The bottled waters were ‘chosen among the French bottled water available’. The tap waters were ‘from various regions of France, supplied by Lyonnaise des Eaux’. The team published their study in the Journal of Sensory Studies in 2010.

The researchers identified what they call the ‘three main tastes of water’ that can be found if one swigs a great variety of bottled and tap waters. These are ‘the bitterness of poor mineralised water, the neutral taste (associated with coolness) of water with medium mineralisation and the saltiness and astringency of highly mineralised water.’ The report concludes that ‘most consumers cannot distinguish between bottled water and tap water when the latter is chlorine-free’. But most is not all. The report goes on to say: ‘However, 36% of the subjects were found able to distinguish between tap water and bottled water.’

Five years earlier, in Belfast, Deborah Wells had run a similar test, with slightly more than one thousand people tasting water from several sources. These included ‘one of the UK’s most popular brands of still bottled mineral water (Evian, Danone Waters), distilled water (supplied by Queen’s University Belfast), and tap water (supplied to Belfast by the Water Service from the Silent Valley, Co. Down)’. Wells, a senior lecturer in psychology at Queen’s University, then wrote a report called ‘The Identification and Perception of Bottled Water’, which appeared in the journal Perception.

‘The findings from this study indicate that people cannot correctly identify bottled water on the basis of its flavour’, she declares. This ‘suggests that the currently high consumer demand for this beverage must be based on factors other than taste or olfactory perception’.

That thought was not entirely new.

In 2004, we awarded the Ig Nobel Prize in chemistry to the Coca-Cola Company of Great Britain. The company has long publicized the existence of a ‘secret formula’ for its signature cola beverage. The key ingredient is water. But that’s not what won them the prize. They were honoured for using advanced technology (mostly pumps) to convert ordinary tap water (obtained from Thames Water, in Sidcup) into Dasani, a pricey, water-filled bottle. It sold briskly – until news broke that Dasani was just bottled tap water.

But … it wasn’t ‘just’ bottled tap water. As the Guardian reported on 20 March of that year: ‘The entire UK supply of Dasani was pulled off the shelves because it has been contaminated with bromate, a cancer-causing chemical.’

Teillet, Eric, Christine Urbano, Sylvie Cordelle and Pascal Schlich (2010). ‘Consumer Perception and Preference of Bottled and Tap Water’. Journal of Sensory Studies 25 (3): 463–80.

Wells, Deborah L. (2005). ‘The Identification and Perception of Bottled Water’. Perception 34 (10): 1291–2.

In brief

‘Metal Detectors: An Alternative Approach to the Evaluation of Coin Ingestions in Children?’

by S.P. Ros and F. Cetta (published in Pediatric Emergency Care, 1992)

Big belly data

Confident that no one would notice what he was doing, Michael Nicod spent months in the homes of families he did not know, making detailed notes about everything they ate. Nicod was performing research for Britain’s Department of Health and Social Security in 1974. He and his colleague, University College London professor Mary Douglas, wrote a report called ‘Taking the Biscuit: The Structure of British Meals’.

Nicod and Douglas wanted to identify what typical British persons see as the essential parts of their typical meals. The pair drew on their training as anthropologists: ‘We imagined a dietician in an unknown Papuan or African tribe wondering how to introduce a new, reinforcing element into tribal diet. We assumed that the dietician’s first task would be to discover how the tribe “structured” their food.’

Table 3 versus Table 5 from ‘Taking the Biscuit’. Say the authors: ‘It is no surprise to the native Englishman that the distinction between hot and cold is much valued in this dietary system.’

Nicod lived as a lodger with ‘four working-class families where the head was engaged in unskilled manual labour’, in East Finchley, Durham, Birmingham and Coventry. He stayed in each place at least a month, ‘watching every mouthful and sharing whenever possible’.

Nicod and Douglas express confidence in the obliviousness of the natives. ‘We reckon’, they write, ‘that after 10 days of such a discreet and incurious presence, the most sensitive housewife, busy with her children, settles down to her routine menus.’

Many others have imagined new ways to examine and change the eating habits of persons other than themselves.

In 2008, Mariana Simons-Nikolova and Maarten Bodlaender of the Netherlands applied for a patent for an electro-mechanical process they call ‘Modifying a Person’s Eating and Activity Habits’. Their video/computer system would monitor an individual’s head and hands to detect when they were eating. It would then announce to them via the TV or computer, ‘You Are Now Eating’. Simons-Nikolova and Bodlaender explain: ‘By providing the feedback when the subject is still eating or drinking, the subject is helped to stop the eating or drinking sooner than if no feedback had been given.’

A 2008 patent by three Israeli inventors describes ‘a sensor which detects: (a) the patient swallowing, (b) the filling of the patient’s stomach, and/or (c) the onset of contractions in the stomach as a result of eating’. Electric current can then, for dietary reasons, be ‘driven into muscle tissue of the subject’s stomach’. This ‘induces in the subject a sensation of satiation, discomfort, nausea, or vertigo’. The entire plan, they say, pertains to ‘appetite regulation, and specifically to invasive techniques and apparatus for appetite control and treating obesity’.

Fig. 1 of 15 from the 2008 patent ‘Regulation of Eating Habits’

Three Indian inventors filed a patent application in 2010 for a ‘refrigerator for obese persons’. The fridge monitors ‘all eating and drinking’, and dispenses diet advice. Also, ‘a reflecting mirror film on the door makes the person to control overeating as soon as he stands before the fridge’.

With these and related plans society becomes more equipped for ‘watching every mouthful’ of some of its members.

Douglas, Mary, and Michael Nicod (1974). ‘Taking the Biscuit: The Structure of British Meals’. New Society 19: 744–77.

Simons-Nikolova, Mariana, and Maarten P. Bodlaender (2008). ‘Modifying a Person’s Eating and Activity Habits’. European patent no. 1,964,011, 3 September.

Aviv, Ricardo, Ophir Bitton and Shai Policker (2008). ‘Regulation of Eating Habits’. US patent no. 7,437,195, 14 October.

Anandampillai, Aparna Thirumalai, Vijayan Thirumalai Anandampillai and Anandvishnu Thirumalai Anandampillai (2010). ‘Refrigerator for Obese Persons’. US patent application 12/799,645, 14 October.

May we recommend

‘Exponential Nonnegativity on the Ice Cream Cone’

by Ronald J. Stern and Henry Wolkowicz (published in SIAM: Journal on Matrix Analysis and Applications, 1991)

Gruel world

Our relationship with cooked cereal owes much to Louis J. Lee of Rochester, New York. Thanks to him, we no longer need to chew the stuff as much as we once had to.

Lee solved a problem that he described in 1963 in a US patent application. He explained that cooked cereals ‘tend to become pasty on cooking and to lose particle texture and flavor on prolonged heating … In many commercial eating establishments, particularly in cafeterias, it is customary to cook up a large batch of a cooked cereal … After several hours on a steam table it is not unusual for a batch of cooked cereal to become a congealed, gelatinous mass. As a result, the batch is unappetizing in appearance and taste and usually is dumped into a garbage can without further ado.’

Lee also gave us a handy, professional definition of ‘cooked cereals’. These, he wrote, ‘are prepared foodstuffs of grain … which usually must be cooked for a short period of time in boiling water in order to be in a normally edible condition … cooking causes the dehydrated grain particles to absorb water and to soften, making the same palatable and digestible.’

Mr Lee is an unsung hero of modern quick-cooking hot cereal. His innovation was, from a chemist’s point of view, simple (though some breakfasters may find it rather over-syllabic for their taste). The Lee method is to cook the cereal mixed together ‘with an edible monoglyceride of the chemically saturated type’.

Three decades earlier, William C. Baxter of Newtown, Connecticut, looked at a different aspect of the cereal-chewiness problem. Baxter found out what happens when you combine shredded wheat with ice cream.

This hybrid foodstuff, Baxter pointed out in a patent obtained in 1936, ‘is really delectable only when the cereal pieces, when taken into the mouth with an intermingled mass of ice cream, are in fairly crisp condition, by which I mean a condition such that these cereal pieces are not yet soggy, although somewhat moist along and immediately below their superficies’.

Baxter’s patent might, in the long run, be best remembered for one poetical passage. Read it aloud to your family each day over breakfast (or, even better, confide it to some stranger at your coffee shop): ‘In the ordinary eating of shredded wheat biscuit with milk or cream, if a thin milk is used and the biscuit is allowed to soak even for a comparatively short time in a pool of such milk, the disk is an unappetizing and highly unsatisfactory one, except to those who for lack of teeth or otherwise enjoy mush, whereas, if the lacteal fluid employed is a heavy or medium cream and if the biscuit and such fluid are together consumed even by a very slow eater, the pieces of the biscuits spooned off or otherwise segregated for each bite carry suitable portions of the lacteal fluid on their surfaces and within their interstices and yet there is a certain definite and desirable crisp-chewability retained by said pieces.’

Lee, Louis J. (1963). ‘Process for Preparing a Cooked Cereal and the Resulting Product’. US patent no. 3,113,868, 10 December.

Baxter, William C. (1936). ‘Food Product and Method of Making Same’. US patent no. 2,065,550, 29 December.

Further cereal studies: milk, then water, then pliers, then milk

After generations of humans had been pouring cows’ milk onto breakfast cereal flakes and then pouring that milk/flake mixture into themselves, a researcher named Luigi Degano fed breakfast cereal to twenty-one cows in Italy. Degano wanted to see how this might affect the milk that later issued from the cows.

Degano, based at the Istituto Sperimentale Lattiero Caseario in Milan, published the results of this feed-flakes-to-cows experiment in 1993 in the journal Tecnica Molitoria.

Degano called the study ‘Cereal Flakes in Milk Cows Diet: Effects on Yield and Milk Quality’. He reported that yes, mixing plenty of maize-and-barley flakes into the cows’ usual, unflaked maize-and-barley fodder did result in different milk. Slightly different. Those cows gave about 2 percent more milk (by volume), with about 2 percent richer protein content and about 2 percent greater creaminess. All this as compared with the milk-making of twenty-one cows that munched only the usual mealy mush.

Degano’s monograph seems to have attracted little attention, at least in print, from other dairy scientists. And it garnered just about no acclaim from the general public in Italy or abroad.

Scientists have, as a group, shown more interest in cereal’s crispness, especially as it interacts with liquid, than in how the flakes interact with cows or with human innards.

The most famous report, ‘A Study of the Effects of Water Content on the Compaction Behaviour of Breakfast Cereal Flakes’, was published in 1994, in the journal Powder Technology. Three scientists at the Institute of Food Research in Norwich wrote it.

In 2001, a student named Kunchalee Luechapattanapom, at the Asian Institute of Technology in Bangkok, Thailand, submitted a master’s thesis entitled ‘Acoustic Testing for Evaluating the Crispness of Breakfast Cereals’. Luechapattanapom describes the basics, in this physico-mathematical passage: ‘Three brands of breakfast cereals, i.e. Kellogg’s corn flake, Honey Stars and Koko Krunch were evaluated their crispness using acoustic testing and mechanical testing. The sound was produced by crushing the samples with the spring loaded pliers. The original amplitude-time curves were converted to the power spectrum of frequencies by using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).’

Others, too, tried their hand at the flake analysis game, generally using either the Norwich or the Bangkok approach.

Steps for forming novel dry milk pieces

But Lawrence Edward Bodkin Sr, an inventor in Jacksonville, Florida, may have circumvented such traditional worries about milk and breakfast cereal flakes, by combining the two elements into one. In 1998, Bodkin patented a foodstuff he calls ‘Breakfast Cereal with Milk Pieces’. Bodkin’s odd patent describes a ‘commingling and packaging of milk nuggets with cereal pieces … The milk pieces may be compact, or flattened and flake shaped and may generally be as variable as the shapes of the cereal’. Any strangeness in the milk’s flavour, he writes, ‘is unlikely to be noticed due to the typically more dominant flavors of the cereal’.

Drawing: ‘a quantity of prepared cereal, in a popular shape containing milk aggregates or milk pieces of a size and shape comparable to those of the cereal’

For their rigorous analysis of soggy breakfast cereal, Georget, Parker and Smith were awarded the 1995 Ig Nobel Prize in physics.

Degano, Luigi (1993). ‘Cereal Flakes in Milk Cows Diet: Effects on Yield and Milk Quality’. Tecnica Molitoria 44 (1): 5–14.

Georget, Dominique M.R., Roger. Parker, and Andrew C. Smith (1994). ‘A Study of the Effects of Water Content on the Compaction Behaviour of Breakfast Cereal Flakes’. Powder Technology 81 (2): 189–95.

Luechapattanapom, Kunchalee (2001). ‘Acoustic Testing for Evaluating the Crispness of Breakfast Cereals’. Thesis submitted in the partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of master of science, Asian Institute of Technology, School of Environment, Resources and Development, Bangkok, Thailand, August.

Bodkin Sr, Lawrence Edward (1998). ‘Breakfast Cereal with Milk Pieces’. US patent no. 5,827,564, 27 October.

Meticulously spirited handwriting

A research project in Turkey examined whether and how drinking affects the quality of one’s writing. This was ‘hard’ rather than ‘soft’ science – it ignored anything fuzzy and hard-to-measure, such as the literary quality of the writing, or its emotional content. The experiment focused, with great discipline, on something that can be gauged more objectively: the extent to which drinking makes people’s penmanship go wobbly.

The goal: to establish that a sometimes-suspect criminal justice tool is dependable, accurate and precise.

Faruk Acolu, at the Council of Forensic Medicine, in Istanbul, and Nurten Turan, at the University of Istanbul, published their study in the journal Forensic Science International. It is called ‘Handwriting Changes Under the Effect of Alcohol’.

They describe going to the annual party of one of Turkey’s most prominent companies, soliciting volunteers from among the attendees. Each volunteer took a breath test and then filled out a questionnaire. ‘Two of the participants’, the report reveals, ‘could not complete the text after consumption of alcohol, and therefore they were excluded.’

Handwriting, when sober (top) and under the influence (bottom)

Seventy-three volunteers did go through the full rigours of the experiment. Each sat at a well-lit desk and copied out a standard passage of text onto an unlined pad of paper. They did it when sober, and then again when intoxicated.

To achieve intoxication, the report explains, ‘The participants consumed ethyl alcohol without limitation’. Each individual was permitted to select and guzzle his or her favourite kind of drink. Twenty-three of them attained a condition of moderate tipsiness (with alcohol-in-their-blood levels of less than fifty milligrams per one hundred millilitres – 50 mg/100 ml). Twenty-four became middling tipsy (with levels between 51mg/100ml and 100mg/100ml). The other twenty-six got sloshed.

Acolu and Turan then compared the writing samples done while sober with those produced under the influence of drink. They used good equipment – an Olympus X-Tr stereo microscope, with direct and oblique angle lighting, and a VSC 2000 Foster and Freeman video spectral comparator. Each handwriting sample yielded up a twenty-six-item checklist full of data: word length, height of upper-case character bodies, variation in spacing between words, number of visible ‘tremors’, number of misspellings and so on. The published report includes, with the statistics, some lovely photos of before-and-after samples.

Acolu and Turan found pretty much what they had hoped to find – evidence that most people’s handwriting gets worse and worse as they become more and more intoxicated. However, they write – with perhaps just a hint of disapproval or maybe even disappointment – that ‘the writing quality of a few seemed to get better after alcohol consumption’.

Drunk handwriting, by the numbers

Why go to all this trouble? Because, Acolu and Turan say, the results of previous studies done by other people ‘are mostly not based upon statistical data and [are] therefore unsatisfying’.

Does the report constitute proof that handwriting analysts can reliably discern the relationship between penmanship and drunkenness? No. But for anyone who takes drunken handwriting seriously, it’s a step in the right direction.

Acolu, Faruk, and Nurten Turan (2003). ‘Handwriting Changes Under the Effect of Alcohol’. Forensic Science International 132 (3): 201–10.

Scientists down the pub

To answer the question, ‘What happens when people drink alcohol?’ one can read through thousands of research studies published in respected scholarly journals. One must look a bit harder to answer a different question: ‘What, exactly, did some of those researchers hope to learn by doing that research?’

Let’s take a quick hop through the literature in one publication – the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, which boasts of being ‘the oldest alcohol/addiction research journal currently published in the United States’. It started life in 1940 as the Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, then adjusted and re-adjusted its name as research funders changed their focus or preferred vocabulary.

A study called ‘Observational Study of Alcohol Consumption in Natural Settings: The Vancouver Beer Parlor’ appeared in a 1975 issue. Authors Ronald Cutler and Thomas Storm, at the University of British Columbia, say they visited ‘approximately 25’ Vancouver beer parlours, wherein they observed the patrons. They distil what they learned into three thoughts: 1) people drank at a ‘relatively constant’ rate; 2) the longer people spent drinking, the more they drank; and 3) in bigger groups, people spent more time drinking, and so drank more drinks. Cutler and Storm explain that ‘these findings are consistent with’ those reported ten years earlier in a study called ‘The Isolated Drinker in the Edmonton Beer Parlor’. Cutler and Storm say the Edmonton researcher behind that report, R. Sommer, ‘found that patrons drinking alone ordered an average of 1.7 glasses of beer, while patrons drinking with a group ordered an average of 3.5 glasses. This difference was accounted for by the length of time solitary and group drinkers spent in the beer parlour and not by the rate of drinking.’

Cutler and Storm performed additional research. Perhaps their most ambitious work, called ‘Observations of Drinking in Natural Settings: Vancouver Beer Parlors and Cocktail Lounges’, published in 1981, says: ‘The question that, to a great extent, motivated this study was: how much do people actually drink in drinking establishments which are most heavily patronised by ordinary social drinkers? The answer is, in qualitative terms: a fair number of people drink quite a lot, especially in beer parlours, and particularly when the group is large.’

Jump ahead to July 2012 and one finds a study, entitled ‘Daily Variations in Spring Break Alcohol and Sexual Behaviors Based on Intentions, Perceived Norms, and Daily Trip Context’, by Megan Patrick, of the University of Michigan, and Christine Lee, of the University of Washington in Seattle. Patrick and Lee gathered information from 261 American university students, from which they learned this: ‘Students who went on longer trips, who previously engaged in more heavy episodic drinking, or who had greater pre–Spring Break intentions to drink reported greater alcohol use during Spring Break. Similarly, students with greater pre–Spring Break intentions to have sex, greater perceived norms for sex, or more previous sexual partners had greater odds of having sex.’

Cutler, Ronald E., and Thomas Storm (1975). ‘Observational Study of Alcohol Consumption in Natural Settings: The Vancouver Beer Parlor’. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 36 (9): 1173–83.

Sommer, R. (1965). ‘The Isolated Drinker in the Edmonton Beer Parlor’. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol 26 (1): 95–110.

Storm, Thomas, and Ronald E. Cutler (1981). ‘Observations of Drinking in Natural Settings: Vancouver Beer Parlors and Cocktail Lounges’. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 42 (11): 972–97.

Patrick, Megan E., and Christine M. Lee (2012). ‘Daily Variations in Spring Break Alcohol and Sexual Behaviors Based on Intentions, Perceived Norms, and Daily Trip Context’. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 73 (4): 591–6.

May we recommend

‘The Influence of Bars on Nuclear Activity’

by Luis C. Ho, Alexei V. Filippenko and Wallace L.W. Sargent (published in the Astrophysical Journal, 1997)

The authors, at the University of California, Berkeley, and Palomar Observatory, report that: ‘The presence of a bar seems to have no noticeable impact on the likelihood of a galaxy to host either nuclear star formation or an active galactic nuclei.’