Technology legal agreements. They pain us so much that when we see them, we often look the other way. We ignore them though they’re in our direct line of sight, and turn a shoulder when they’re front and center. When directly asked to confirm that we read them, we lie.

I have understood . . .

Check!

I have read . . .

Continue!

I will obey . . .

Submit!

In fact, you’ve probably already spent more time reading this chapter than you ever have spent reading a technology legal agreement because doing so is digital torture.

Want Wi-Fi? Oh sure, it’s free. Just step right up, now. Step right up, son, and see the one, the only, the ad-free legendary speeds here! Now, first, I’ll just have you lie down on this shiny guillotine . . . !

The rope is pulled . . . Latin phrases . . . !

The blade falls . . . impossible-to-follow run-on sentences . . . !

The crowd gasps . . . all caps for emphasis . . . !

Your head and your rights roll away in a confusing mess.

IF THESE LAWS APPLY TO YOU, SOME OR ALL OF THE ABOVE DISCLAIMERS, EXCLUSIONS, OR LIMITATIONS MAY NOT APPLY TO YOU, AND YOU MAY ALSO HAVE ADDITIONAL RIGHTS.1

Above? Oh, that’s just one nonspecific, legalese phrase from the iTunes terms and conditions—an ever-evolving document that’s about the length of 56 printed pages,2 so absurdly overwhelming and long that roughly 500 million of us have dealt with it like a waterboarded confession.3

There’s probably something we should read about our privacy in that long, mundane, and exhausting document, but there’s also a good reason mental impairment can cause false confession.4

In Redmond, Washington, where they’ve reported that 1.1 billion people use Microsoft Office,5 they’ve even included text in their software license agreement to play “good cop” and let us know how we should read their own confusing text:

THE ADDITIONAL TERMS CONTAIN A BINDING ARBITRATION CLAUSE AND CLASS ACTION WAIVER. IF YOU LIVE IN THE UNITED STATES, THESE AFFECT YOUR RIGHTS TO RESOLVE A DISPUTE WITH MICROSOFT, AND YOU SHOULD READ THEM CAREFULLY.6

“Read them carefully.” Sure, that sounds fun.

Say we attempted to swim out of the mental drowning, and we actually carefully read privacy policies starting with just the websites we visited. How long would it really take all of us to collectively read those privacy policies?

About 54 billion hours.

The answer comes from Carnegie Mellon researchers Lorrie Faith Cranor and Aleecia McDonald, who set out to explore the real cost of lengthy and complex privacy policies in the United States. Amongst their measurements, they had 212 participants “skim” for “simple comprehension” the privacy policies of some of the most popular American websites. Combining that information with a variety of other data, such as individual browsing habits from Nielsen, they estimated how long it would take the typical American to read the privacy policies of the websites they commonly visited. What they discovered is that the torture is extensive.7

OK, if I use this fork, I can probably dig out a tunnel in 2.25 million days.8

Assuming that we read privacy policies like it was our job (for eight hours a day), Cranor and McDonald estimated it would take the individual American 76 work days to read the privacy policies of the common web-sites they visit. And that doesn’t include apps. Extrapolated out to the population of the United States, according to their research, it would take up about 53.8 billion hours for the country to read the privacy policies of just the websites they frequently visit.

The financial cost of all that tedious reading?

If paid just 25 percent of our salary to read the privacy policies, it would cost us $781 billion in time. And, yes, we’re still just talking about only the websites you frequently visit.

Terms and conditions are long, boring, complex, expensive, painful, and another step between us and our goals. But as more and more new services emerge, and our data exists in more places, the more important those policies become.

Think back to when you signed up for Friendster. Or MySpace. Or Facebook. Or Instagram. Or Ello. Or that other hot new service.

First, you just share the interesting basics at convenient times. Then, things accelerate. Trust grows. You tell your friends. You see each other more often. Share everything. Always. Anything. You love the feedback. Wear your heart on your posts. You get hooked. You get so many likes and favorites. It becomes a passion.

And then the social network you’ve been dating changes its privacy policy and all your secrets leak out. Your cousin tags you, Mom sees your photos from Spring Break at Destin, Florida, and your karaoke medley of Queen hits goes viral. Shit. All of a sudden, you’re a privacy advocate even more afraid of Latin and all caps.

Due to its popularity and historically poor execution on privacy, Facebook is a common modern target in the social world for privacy advocates. So Facebook recently did what anyone would do. They had an engineering team—which is probably great at writing code—add something to their site that they thought would reduce the fear: a cartoon dinosaur.

“Our team looked at a few different characters, saw the dinosaur and just thought he was the friendliest and best choice,” a Facebook engineering manager told the New York Times in 2014.

To better explain their privacy policy, Facebook created a mascot to explain where your posts are going to end up.

What?

This is a time of privacy madness, a bizarre tipping point when the largest social network has chosen to use a cartoon dinosaur to explain their ever-changing privacy policy settings,9 when a US privacy savior has been banished to Russia, and when an enormous American search engine has caused so much paranoia about privacy that it has gone on tour in Europe to convince its citizens that their own courts are misguided about privacy.10

Meanwhile, back in the United States, according to Pew Research Center, 68 percent of Internet users believe that our current laws are “not good enough in protecting people’s privacy online.”11 And as we jump from service to service, our data and our personal information lie in multiple servers we may have forgotten.

It’s like having 20 ex-wives or -husbands running around town with the ability to reveal your most embarrassing secrets to the world.

Some say these worries are a soon-to-be passé issue. That once the next generation grows up, all these privacy concerns will fade away like 1956 paranoia about Elvis Presley’s swinging hips.12

“As younger people reveal their private lives on the Internet, the older generation looks on with alarm and misapprehension not seen since the early days of rock and roll,” says a subheader from New York Magazine.13

The chief privacy officer at the computer security company McAfee (the antivirus guys) has concurred. “Younger generations,” she once told USA Today, “seem to be more lax about privacy.”14

But despite your struggles with your daughter’s Instagram, studies have shown the opposite: Privacy actually does matter to teens. Given all that is shared—photos, videos, animated GIFs—the idea that the upcoming generation does not care about privacy seems false. After all, with more on the table, there’s more to lose.

Your teenage daughter may not have anything to hide from the government, but she probably doesn’t want her friends (or enemies) to get that video of her chicken wing dance moves from Aunt Eleanor’s wedding. As Molly Wood from the New York Times once wrote, “The second generation of digital citizens—teenagers and millennials, who have spent most, if not all, of their lives online—appear to be more likely to embrace the tools of privacy and protect their personal information.”15

That’s probably why the concept of quickly exploding messages on services like Snapchat are popular among teens. A recent Pew study revealed 51 percent of American teens (aged 12 to 17) have avoided certain apps “due to privacy concerns” and 59 percent of American teenage girls disable location awareness out of fear of being tracked.16

Similar results have shown up in research by top universities. At Harvard’s Berkman Center, researchers collaborating with Pew found that 60 percent of American teens had manually set their Facebook profiles to private (friends only) before it became the default option.17 In a collaborative study from UC Berkeley and the University of Pennsylvania,18 researchers found that “large percentages of young adults (those 18 to 24) are in harmony with older Americans regarding concerns about online privacy, norms, and policy suggestions.”19 Obnoxious over-sharers stand out, but the average teenager seems to place the same value on privacy as her previous generation.

If, going forward, we continue to evolve our technological experiences, and we step into a No Interface world in which technology is built to understand your needs, collecting data about your preferences can be a powerful tool. It can allow systems to achieve currently unfathomable advancements in technology that change the way you live. But to truly succeed, those new products and services need to be created with ethical policies desired by this generation and the next.

So, how do we end the waterboarding? How do we fix the problem of legal agreements so that we can take this leap forward?

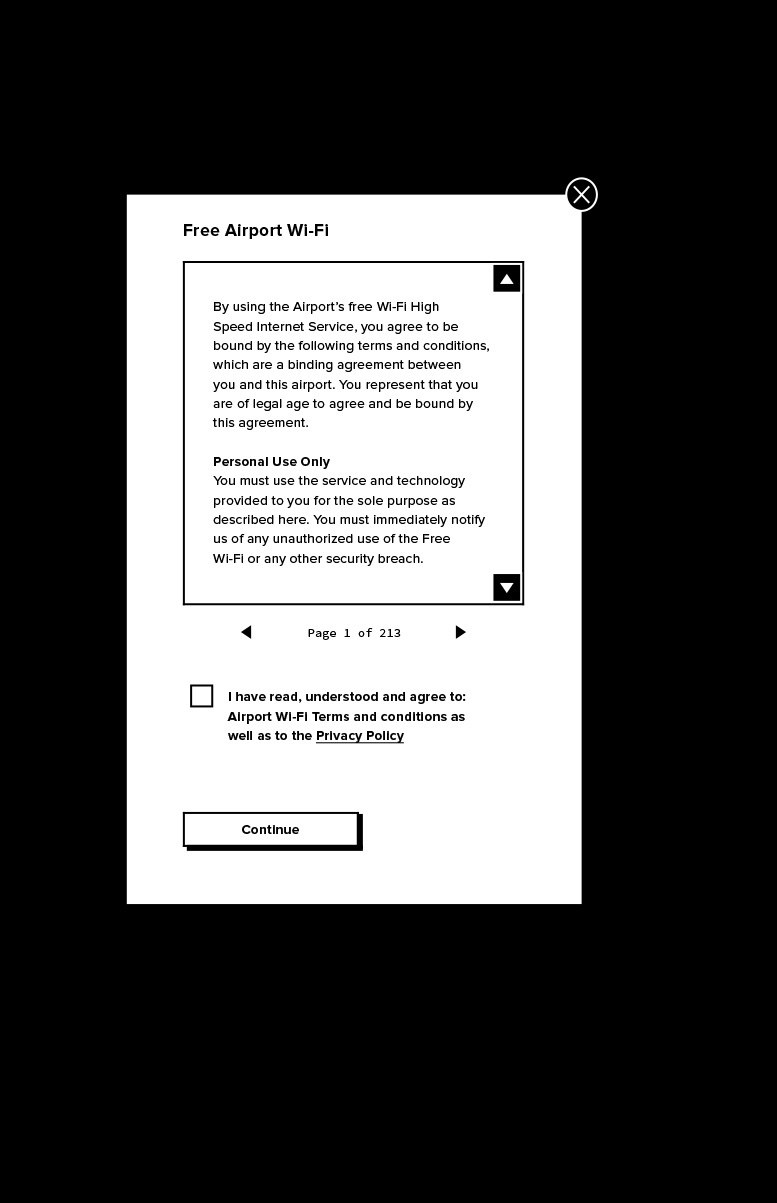

Should we force users to scroll to the bottom of a privacy policy before allowing them to continue to install a program in hopes that’ll make them read the legal terms? More all caps so everything seems more important? A pop-up warning that they should really read the terms? A more robust checkbox confirmation method? Better typographic formatting?

Nope. Instead, embrace reality: It’s mental torture, and the average user is probably never going to read legal agreements.

Not long ago, a company called PC Pitstop shipped a popular piece of software called Optimize. It scanned the entire contents of your personal computer—your personal documents, your images, your music, and more—to identify any common problems that could be slowing down your computer.

For scanning software like Optimize, which could be potentially sifting through your sensitive password or bank information, privacy is hugely important. Curious about how long we’re comfortable sitting in the boredom gas chamber to actually read our rights, PC Pitstop secretly altered their end user license agreement (EULA) to include a section about how to get a free cash prize, just in case anyone actually had the pain tolerance to read that far into the document.

Months passed. Thousands of sales. No one cashed in.

But then, on one surprising day, after over three months and nearly 3,000 sales, a customer contacted the company to claim the prize. He received a well-earned $1,000 check.

Maybe it was an unethical experiment, but their discovery revealed a pattern.

A few years later, a UK retailer indulged a similar curiosity. Gamestation, which at the time sold new and used video games, inserted a special clause into their sales contract with online customers: They asked you to sell your soul to them. Seven thousand five hundred people agreed to the clause, probably unknowingly handing over the rights to their souls.20

Quick: What’s the average time someone actually spends looking over the terms and conditions of software? Seventy-four work days? Ten work days? Five? How long do you think we’re willing to spend on the torture rack?

Roughly one and a half to two seconds.21

Make it stop! I’ll check the box! I agree! My troops are hiding behind the mountain!

Most of us would make terrible spies.

That number comes from Tom Rodden, a professor of computing at the University of Nottingham,22 who has found that we tend to spend just a few forgettable moments considering the agreements we check off every time we install a snazzy new app, 15 times less than we spend watching a 30-second television ad for toilet paper.

(Source: “Big Data: Seizing Opportunities, Preserving Values,” Executive Office of the President, White House 2014)

Even if some of the smartest people in tech legal managed to triple the amount of time people spent reading terms and conditions, you’d still only be at six seconds of reading per agreement.

Instead, a greater return on our efforts might occur with improving other things in the experience that could help us manage our privacy.

For one, the bland settings menu.

In 2014, President Barack Obama called for a “90-day review of big data and privacy.” Over 24,000 people were surveyed about a variety of issues. One of the most striking findings was that 80 percent of the respondents were “very much” concerned about transparency of data use.23

That same year Microsoft released their first version of Cortana, a voice assistant. There are a lot of interesting things to discuss from their initial work, but one thing that stands out, believe it or not, is their settings menu. I’ll recreate it here for you:

What’s so striking? The simple, straightforward, transparent, plain English. The understandable explanations under switch buttons. The ability to change your name with ease, and no need for a cartoon dinosaur. With potentially 80 percent of the US population concerned about transparency in data collection, an easily understood settings menu—including such things as a simple checkmark for “Track flights or other things mentioned in your email”—can be much more powerful in gaining trust than forcing someone to scroll through a legal agreement.

Transparent and ethical data collection is a fantastic foundation for privacy. Much more so than LATIN IN ALL CAPS.

In the pursuit of trying to create elegant, No Interface experiences, technology companies will probably need to collect a bit of data about you to make sure they’re doing the right thing.

Say, for example, a startup wanted to make a NoUI experience that made the lights in your bedroom mimic a gentle sunrise just before your alarm clock went off. To make it work, the startup would probably need to know only when you have your alarm clock set. Not your contact list, who you follow on Twitter, or your LinkedIn connections.

Going overboard on data is a good way to lose trust and make customers run the other way, like when it was revealed that the social network Path was secretly copying your smartphone’s address book onto their servers. Yes, they fixed it, and apologized profusely,24 but they had to pay the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) an $800,000 fine,25 and it damaged their public image forever.

Or when Jay-Z made a deal to give his Magna Carta . . . Holy Grail album away as a free app, but the app didn’t play any of his music until you gave away your address book information, your call log, access to your social media accounts, the ability to send messages on those services, your email account, and, unbelievably, a whole lot of other things that had nothing to do with listening to Beyonce’s love talk about his Yankees cap.26 Facing privacy ridicule, Jay-Z himself tweeted “sux must do better.”27

World’s best apology.

All that said, to deliver what you need and when you want it, more advanced NoUI systems may need to learn about some of a user’s general preferences.

Say, for example, you built a back pocket app that attempts to discover a customer’s food preferences to provide him with a custom-tailored food delivery service. He may have flown by the EULA—Yes, I agree!—and given you permission to gather information about his favorite foods from some of his other public channels.

Eventually, through social media posts and shared articles, your software may start to see a pattern around cupcakes. And when your system gains enough confidence that he loves them, you might decide to give him a free delivery of the best cupcakes you can find.

He gets the cupcakes, loves the treat, and now tells everyone about your amazing service.

Cupcakes . . . ? For me!?

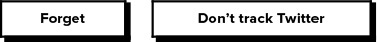

Even though you knocked his socks off, his data about loving cupcakes is still his data. And you should treat it that way. So the app could automatically forget detailed information after a period of time. The act of forgetting that sounds like blasphemy in a world of tech businesses built on advertising, but it is a great way for a reputable company built around data to gain trust.

That event could trigger after success. Perhaps after delighting him with the cupcake delivery, the system could jot down that it successfully delivered a dessert, forget all about the cupcake-specific data, and start again, looking for a new pattern that’s not dessert related.

We got dessert, now what?

Inactivity could be another automatic trigger to erase any stored information. If he hasn’t utilized the system in a long time, his food data could automatically clear. With so many services out there trying to grab our attention, knowing that a system collecting more general information will just forget everything it knows about you if you don’t use it for a long time might ease the resistance to trying out the new software in the first place.

He could even explicitly tell you how long to collect his data. The mobile app Glympse, for example, lets you share your GPS location with a specific set of people within a defined time period.28 You’re walking to meet your friend, you set a 20-minute timer to share your location, so he sees you when it’s relevant, and then shares no data when it’s not relevant.

Or, an easy “let’s start over” button could exist on a physical object or graphical user interface to clear all saved data at any time.

For richer transparency, granular controls could be offered within a list of conclusions, including the observations that led the system to those conclusions, that allow a user to remove those findings. Maybe something like this:

Here’s why we think that:

You posted on Facebook “I love cupcakes!”

You ordered a book about cupcake recipes on Amazon.

You checked in on Foursquare at Kara’s Cupcakes 10 times this month.

You tweeted the word “sprinkles” 42 times in the past 12 months.

You posted a picture of yourself at The Cupcake Factory on Google Plus

Buttons are ugly, and graphical user interfaces aren’t aesthetically elegant. But having explicit controls sitting in the background of a complex system that you can directly manipulate is one way of easing any potential user fear and creating a relationship of trust. The graphical user interface in this case is not the experience; it’s just there for advanced privacy settings.

Look, we’re not going to sit around and spend hours reading through legal documents we don’t understand. It’s first-world torture. We’re eager to get things done and live our lives. But privacy is really important, and when taking technology to the next step we should consider good methods for providing the kind of control—automatic or manual—that lets everyone keep their secrets safe while enjoying the elegance of a system that provides you with what you need.

The best interface is no interface, but that leap forward in technology needs to value privacy or it won’t have success.