THE WITCH-KING OF ANGMAR

Just as the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse in the biblical Book of Revelation were seen as harbingers of an age of destruction and catastrophe, so the reappearance of the ghastly undead Nazgûl Horsemen at the end of the 13th century of the Third Age may be considered the harbinger of an age of destruction and catastrophe. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse symbolize Pestilence, War, Famine and Death, while the reappearance of the Ringwraiths as the chief servants of the Necromancer brings down each of these calamities upon the inhabitants of Middle-earth over the following two millennia. One reading of Revelation (written during the reign of Emperor Diocletian, AD 81–96) ties the Four Horsemen to contemporary history, so that it can be seen as a prophecy of the eventual decline and fall of the Roman Empire. And, certainly, one may see in the return of the Ringwraiths a foreshadowing of the pestilence, war, famine and death that soon came down upon the inhabitants of Arnor and Gondor.

The Nine were also something of a variation on the Old Germanic tradition of the Wild Hunt: a procession of ghostly horsemen or supernatural huntsmen riding through the forests and fields in a mad pursuit of their quarry. In Old English, it was known as the Herlathing (“Herla’s Assembly”), in Old Norse as the “Ride of Asgard”, and in Swedish the “Hunt of Odin”. A memory of it survives in the American country-and-western song “(Ghost) Riders in the Sky: A Cowboy Legend”. Witnessing the Wild Hunt was thought to presage some catastrophe such as war or plague or, at best, the death of the one who saw the cavalcade. Those encountering the hunt might also be abducted to the Underworld or the fairy kingdom. In some instances, it was also believed that people's spirits could be pulled away during their sleep to join the hunt.

Witch-king of Angmar

The leader of these lost souls and undead horsemen was – according to the oldest traditions – Wotan, the German counterpart to the Norse god Odin, but this varied from nation to nation and age to age: other leaders included the Danish King Valdemar, the Swiss Dietrich von Berne, the French Charlemagne, the German Fredrick Barbarossa, the Welsh Gwyn ap Nudd, ruler of the Otherworld, and even the British King Arthur.

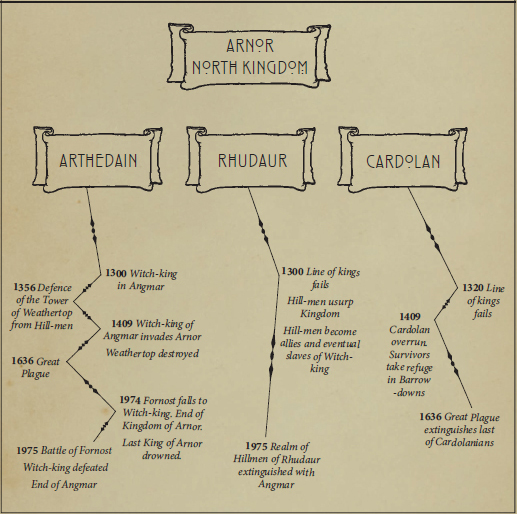

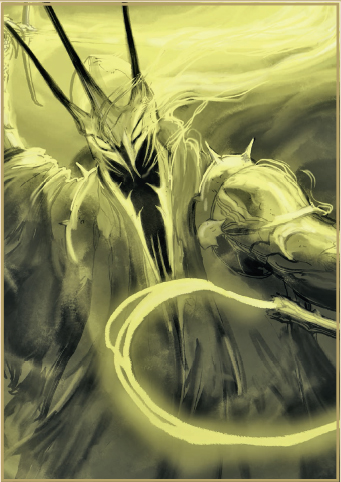

The leader of Tolkien’s nine phantom horsemen is variously known as the Witch-king, the Black Captain and the Lord of the Nazgûl. Around TA 1300, the Witch-king became the ruler of Angmar (meaning “Iron Home”), a realm on the northern borders of Eriador in the foothills of the Misty Mountains. Angmar was the realm of the Hill-men: a pre-Númenórean people descended from the mountain tribes of the White and Misty Mountains. In the context of European history, the Hill-men of Angmar most resemble the Basques, the indigenous mountain people of the Pyrenees straddling modern France and Spain.

For centuries, the Basques fought against Roman, French and Spanish incursions into their lands, and constantly rebelled against those powers. Much as the Basques were resentful of the Roman Empire – or, later, of Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire – the Hill-men are resentful of the Númenórean kings of Arnor. Consequently, the Hill-men are easily corrupted by the Witch-king and persuaded to enter into a disastrous war of attrition. After seven centuries, the Witch-king’s long war ended in TA 1975 with the Battle of Fornost and the mutual destruction of both Arnor and Angmar.

Tolkien’s Witch-king of Angmar is a variation on the widespread tradition of the phantom horseman. In some respects, the Witch-king resembles the Irish Dullahan, the “Dark Man”, a terrifying demonic horseman. By some accounts, each time the Dark Man halts his ride, a death occurs. By other accounts, the Dullahan calls out a name, and whoever is named is seized by death. There are many cultures worldwide where a “Pale Rider” is the archetypal personification of death. On the Irish poet W. B. Yates’s gravestone is the epitaph: “Cast a cold eye / On life, on death, / Horseman, pass by!”

Hill-man of Angmar