GOBLINS, ORCS AND URUK-HAI

In The Hobbit, the narrator warns the reader that the Misty Mountains are made perilous by hordes of “goblins, hobgoblins and orcs of the worst description”. This is an almost entirely redundant phrase as they are all the same creature under different names. For, as Tolkien himself explains in the preface to his novel: “Orc is not an English word. It occurs in one or two places [in The Hobbit] but is usually translated goblin (or hobgoblin for the larger kinds).” Orcs upon Middle-earth, of course, are ever the evil foot soldiers of the Dark Lords Morgoth and Sauron. However, while The Hobbit was written decades after most of The Silmarillion and later texts were conceived, the publishing history of Tolkien novels ensured that readers would first encounter them under the Goblin name.

In the context of his children’s book, The Hobbit, Tolkien needed to somewhat mute the evil nature of his Orcs, and adopted the rather more child-friendly name of “Goblin”, which has more mischievous, even comic associations. In a letter, Tolkien explicitly acknowledged his source of inspiration: “They are not based on direct experience of mine; but owe, I suppose, a good deal to the goblin tradition … especially as it appears in George MacDonald.” Tolkien refers here to the Scottish writer George MacDonald (1824–1905) and his 1872 novel The Princess and the Goblin. Certainly, there is the evidence of that little song included in the novel that Tolkien had read as a child. The song begins: “Once there was a Goblin living in a hole …” This is very close to Tolkien’s opening line in The Hobbit: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” Both Goblins and Hobbits are hole-dwellers, even if they are quite opposite in their nature.

In The Hobbit, Goblins prove to be a major hindrance. Typically, here, as in many fairy tales, we have a children’s fairy-tale geography marked with generic, archetypal names: The Hill, The Water, The Shire, The East Road, The Last Bridge, The Ford, The Old Forest Road, The Forest River, The Long Lake and The Lonely Mountain. And, so, not surprisingly, in the process of travelling through the High Pass in the Misty Mountains, the adventurers find themselves captives of Goblins and their master, the Great Goblin of Goblin Town.

In later years, in his letters, Tolkien speculated on the nature of the Great Goblin of Goblin Town and his power over other Goblins, and suggested that he might be – like Boldog, the Orc Captain of Angband in the First Age – a lesser Maia spirit who has taken on an Orkish hroa, or physical form. This is also likely the case with the only Goblins given individual names in The Hobbit: the powerful Bolg of the North, the Goblin war chieftain in the Battle of the Five Armies, and his father, Azog the Defiler, the Goblin Chieftain of Moria who was slain in the final battle of the War of the Dwarves and the Orcs.

Uruk-hai of Mordor and Isengard

When Tolkien speaks of his borrowing from the goblin tradition, one must acknowledge the intercultural nature of these creatures. His Goblins share many aspects with malevolent creatures from a host of Germanic, Nordic and British traditions: kobolds, bogies, knockers, bugbears, red caps, demons, imps and gremlins. In Asia, there are counterpart evil races such as the Min Chinese kwee kia, Malayan toyol and Cambodian cohen kroh – often evil, twisted spirits animating the bodies of murdered children or foetuses.

Readers who progress from The Hobbit to the high romance of The Lord of the Rings and the epic of The Silmarillion soon discover that Tolkien no longer portrays Goblins simply as comically grotesque walk-on parts, but as an irredeemably evil Middle-earth race in thrall to the Dark Lord. The transformation of Tolkien’s Goblins into the rather more sinister Orcs is comparable to that of the Germanic kobolds. These mischievous household spirits responsible for petty theft and troublemaking evolved over time into dangerous underground spirits haunting caves and mines. The name for the mineral cobalt derives from kobold because medieval miners blamed these demonic spirits for the metal’s poisonous fumes when it was smelted.

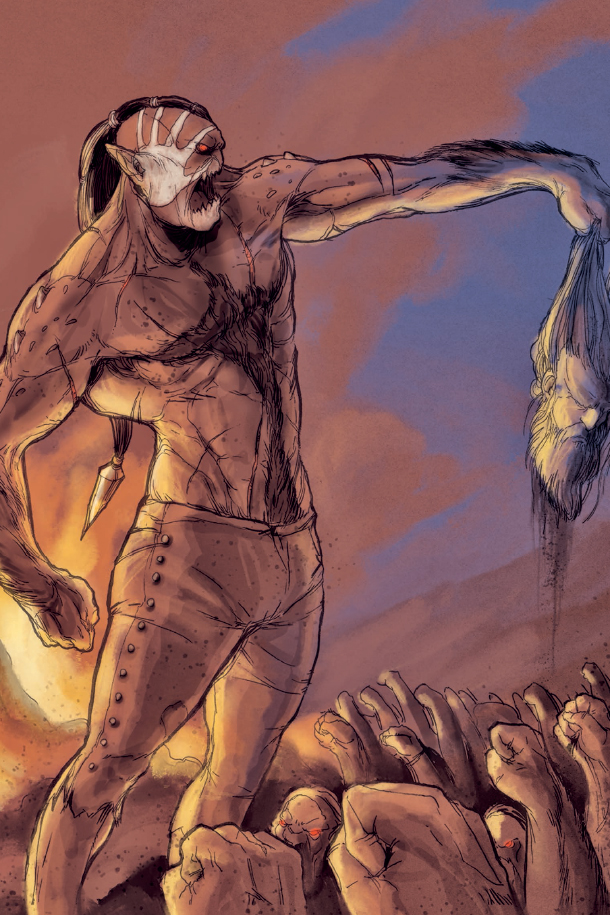

In the 25th century of the Third Age, Sauron released a new and more powerful breed of Orkish soldiery out of Mordor. These were called the Uruk-hai (“Orc-folk”). It has been suggested that these larger and more ferocious forms of Orcs may in part have been inspired by Tolkien’s reading of the 6th-century historian Jordanes’ xenophobic description of the “scarcely human” Huns. Sauron’s Uruks are Orkish in appearance and manner, but the size of Men and could endure and remain strong in sunlight. Certainly, Jordanes’ description of the soldiery of Attila the Scourge of God might easily be applied to Sauron’s Uruks: “Their swarthy aspect is fearful, and they have pin-holes rather than eyes … Broad-shouldered, ready to use a bow and arrow. Though they live in the form of Men, they have the cruelty of wild beasts.”

Sauron’s swarthy Uruks may have resulted from an interbreeding of Orcs and Men. And, like the Huns against the Romans, the Uruk-hai come forth in great numbers against the Men of Gondor. They lay waste to their capital, Osgiliath, and fought in Sauron’s alliance alongside lesser Orcs, Trolls, Easterlings and Southrons for the next five centuries of the Third Age. Then towards the end of the Third Age, Saruman would also breed Uruk-hai in the pits beneath Isengard.

Uruk-hai