SMÉAGOL–GOLLUM AND THE RING

Sméagol–Gollum is among the most complex of the villains portrayed in The Lord of the Rings. He is very far from the pure evil of out-and-out villains such as Sauron and the Ringwraiths, but is instead shown as deeply riven between his better and worse natures.

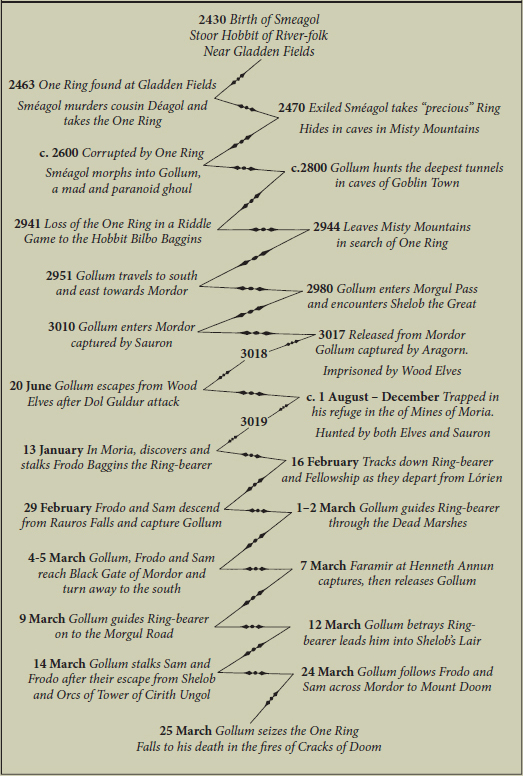

When Sméagol–Gollum first appears in The Hobbit, readers often assume he is some sort of murderous, cannibalistic breed of Goblin that even other Goblins fear. It was only later, in The Lord of the Rings, that Tolkien revealed Sméagol to be in origin a Stoorish Hobbit, who has long been banished from his people and corrupted by the One Ring. In The Hobbit, Gollum is merely one of a number of Bilbo Baggins’s obstacles and trials on his quest to reach the Lonely Mountain. The discovery and acquisition of a magic ring was a simple plot device to give the crafty Hobbit hero enhanced powers comparable to those described in Plato’s ancient Greek legend of the ring of Gyges, which similarly bestowed invisibility on its wearer.

It was not until Tolkien began to write The Lord of the Rings, however, that the author himself discovered the significance of this particular ring. And with this discovery, it became clear to the writer that the character of Sméagol–Gollum was the embodiment of the struggle between good and evil that is crucial to the narrative of this epic tale.

The creation and evolution of the character of Sméagol–Gollum draws on a considerable body of mythology related to ring legends. In the Völsunga saga, the most famous ring legend in Norse mythology, we have Fáfnir, the son of the dwarf-king Hreidmar, who murders his own father in his desire to possess a cursed ring and its treasure. This is comparable to Sméagol’s murder of his cousin Déagol as he covets the One Ring. Retreating like Sméagol to a mountain cave, Fáfnir broods over his ring and eventually transforms into a monstrous dragon. Similarly, Sméagol, who through the power of the One Ring is able to live for centuries, transforms into a ghoul twisted in mind and body – the cannibalistic Gollum brooding over his “precious”.

Gollum

Gollum guides the Hobbits through the Phantom haunted Dead Marches

The Icelandic narrative poem Völundarkvitha reveals another similar ghoul – Sote the Outlaw, who steals a cursed ring that he so fears may be taken from him that he has himself buried alive with it, sleeplessly guarding it with his weapons drawn.

In Sméagol–Gollum, we have a classic case of a split personality, as portrayed in Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) and, most famously, in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886). When Sméagol is in control, he has pale eyes and refers to himself as “I”. When Gollum is at the helm, however, he speaks as “we”, perhaps referring to himself and the Ring collectively (as well as indicating his “split personality”). Just as in Stevenson’s tale, this evil aspect of his being is in perpetual conflict with the good in him.

Whatever Gollum’s obvious defects, one has to admire his ability to survive over a span of nearly six centuries. Even taking into account the legendary renown of Hobbits for stubbornness, Sméagol–Gollum is remarkably enduring. Furthermore, Sméagol–Gollum retains other aspects of his Hobbit nature that likely save him many times from his foes. As a Hobbit, he is almost totally lacking in any ambition or desire for power, and so never uses the power of the Ring to any great extent or for any great purpose. Gollum’s desire seems limited to that of a miser with his gold. Being alone in the darkness with his “precious” is as close to contentment as the tortured soul of Gollum ever comes. Yet, Gollum’s insistence on his ownership of the One Ring is a delusion. Gollum no more possesses the One Ring than an addict possesses a drug. The Ring, indeed, is his addiction – the Ring possesses Gollum.

It is the complex nature of Sméagol–Gollum’s villainy that leads him to play such an ambivalent role in the Quest of the Ring, alternately treacherous and eager to please and ultimately causing good even in his evildoing.