THE WITCH-KING AND THE BATTLE OF PELENNOR FIELDS

King of Angmar long ago, Sorcerer, Ringwraith, Lord of the Nazgûl, a spear of terror in the hand of Sauron, shadow of despair.” This is Gandalf’s description of the Witch-king of Minas Morgul as he lays siege to Gondor’s capital, Minas Tirith.

Although the modern English usage of “witch” usually has female connotations – with “wizard” or “warlock” as the more commonly used names for male users of magic – in giving the chief Nazgûl the title of Witch-king, Tolkien draws on the Middle English verb wicchen, which means simply “to do magic”, without gender distinction.

The full horror of the Witch-king is revealed before the shattered gate of Gondor when the Black Rider pulls back his hood. We are told: “He had a kingly crown; and yet upon no head visibly was it set. The red fires shone between it and the mantled shoulders vast and dark. From a mouth unseen there came a deadly laughter.” Here, Tolkien’s Witch-king fits solidly into the mythological tradition of the headless horseman found in European folk tales, most notably the Irish Dullahan or “Dark Man”, and whose most famous descendant is found in Washington Irving’s Gothic horror story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1820). In the Battle of Pelennor Fields, it becomes clear that the Witch-king has been given much greater demonic powers than the other eight Nazgûl. In battle, his strength is little diminished by daylight, for example.

In the siege of Gondor and the Battle of Pelennor Fields, the Witch-king leads a vast Morgul army of Uruks, Orcs, Trolls, Southrons and Easterlings. However, Tolkien is careful not to show all of the enemies of Gondor as unremittingly evil. Prominent among the Witch-king’s allies are the Haradrim (inhabitants of Harad) who in their pride and courage – not to mention their dazzling, exotic appearance – are granted a certain nobility. We could argue that Tolkien portrays these foes of Gondor in much the same way that medieval crusading epics (chansons de geste) and, later, 19th-century histories of the Crusades characterized the “Saracens” (the Muslim opponents of the Christian Crusaders) as at once praiseworthy and wrong-headed.

Mûmakil: war elephants of the Haradrim

It was the charge of the Rohirrim against just such a Saracen-like Southron cavalry, made up of black-haired “swarthy men” dressed in red and gold with armour made of “overlapping brazen plates”, that transforms the siege of Gondor into the full-pitched Battle of Pelennor Fields. Théoden, King of Rohan, with his green banner marked with a white horse, rides directly to challenge the chieftain of the Haradrim, whose horsemen rally under a red banner emblazoned with a black serpent. “[T]he drawing of the scimitars of the Southrons was like a glitter of stars,” we are told. It is a battle scene full of the oriental romance that we find in Lord Byron’s poem “The Destruction of Sennacherib” (1815), in which: “The Assyrian came down like a wolf on the fold / And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold; / And the sheen of the spears was like stars on the sea, / When the blue waves roll nightly on deep Galilee.” Like the Assyrian King Sennacherib, the Haradrim chieftain is slain and his serpent standard is “hewed staff and bearer”.

The moment of Rohirrim victory turns to disaster, however, when the Witch-king, mounted on his terrifying Winged Beast, strikes down Théoden and swoops down to deal the fallen king a death blow. As the other Rohirrim fall back in fear and despair, the Witch-king is challenged by Dernhelm, a slender young knight of the Mark. Scornful of this mismatched duel, the Witch-king is supremely confident, believing that he is protected by the age-old prophecy that “not by the hand of man will he fall”. In this duel, Tolkien is drawing on that ancient theme in myth and literature known as the “Misinterpreted Oracle”.

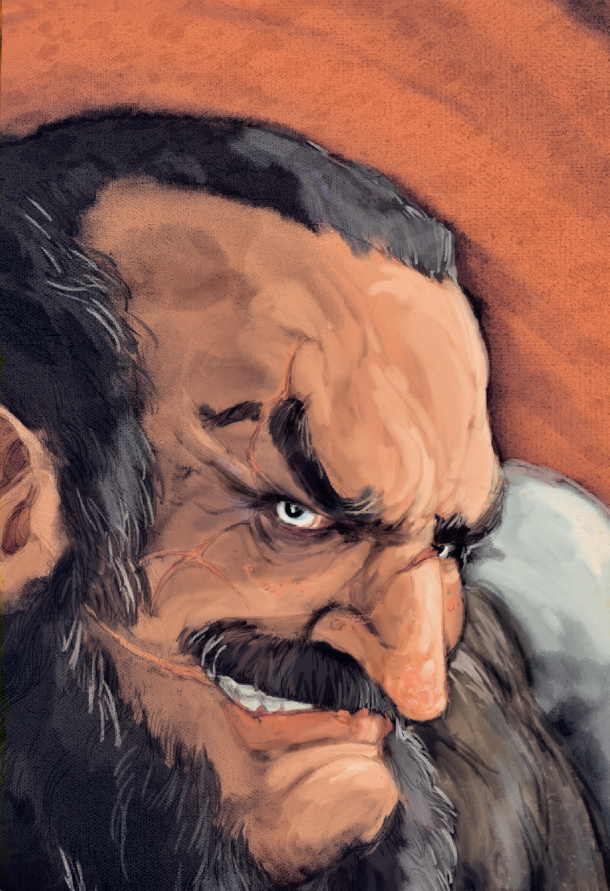

Chieftain of the Haradrim

Among the most famous of these tales of misunderstood prophecy is one from the Histories of 5th-century-BC Greek Herodotus about Croesus, the rich and powerful king of Lydia who consulted the Delphic Oracle about his planned invasion of the Persian Empire. The Oracle replied: “If Croesus goes to war, he will destroy a great empire.” It was a prophecy that proved ironically and tragically true, for the empire that Croesus destroyed proved to be his own. More pertinent still to the fate of the Witch-king, as Tolkien himself acknowledged, is the witches’ prophecy found in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (and in its source, Holinshed’s Chronicles) that the murderous Scottish king should “laugh to scorn / The power of man, for none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth.” The Witch-king’s prophecy “not by the hand of man will he fall” is almost the same safeguard that appears to protect Macbeth, who at the end of the play is killed by Macduff who “was from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripp’d”.

Similarly, the prophecy concerning the Witch-king’s fate also proves true in an unexpected way. For indeed, the Witch-king falls “not by the hand of man” but by the hand of Dernhelm, who is suddenly revealed to be the sword-maiden Éowyn of Rohan. And so, with the aid of her Hobbit squire, Meriadoc Brandybuck, Éowyn fulfils the ancient prophecy and with a thrust of her sword brings an end to the once-mighty Witch-king and Lord of the Nazgûl. With his fall, the tide of the Battle of Pelennor Fields turns, and all the Witch-king’s ambitions of lordship and conquest are brought to nought.

Tolkien implied that his own resolution of this kind of riddling prophecy was an improvement on Shakespeare’s fulfilment of the prophecy about Macbeth. And, certainly, one must acknowledge that the Witch-king’s death by the hand of a Hobbit and a woman disguised as a warrior is rather more satisfying than Shakespeare’s rather quibbling solution that someone born by Caesarian section is not, strictly speaking, “of woman born”.

Battle of Pelennor Fields