1

Mr. Monk and the Phenomenological Attitude

TALIA WELSH

In “Mr. Monk Gets a New Shrink,” as in most episodes, it is Monk’s incredible perceptive powers that solve the case. Monk notices not only what a very attentive detective might capture—such as the fact that the carpet was just vacuumed and the vacuum bag is empty—but he also notices that a small decorative rock has been moved. What strikes the audience and Dr. Kroger is how astounding it is that Monk would remember such a small detail. Dr. Kroger comments, “It’s amazing that you remember one particular rock,” to which Monk replies “Well, I’ve been staring at it for nine years; you know, gift ... curse ...”

But what is really amazing here? It certainly isn’t strange to look at something for nine years. We don’t move around constantly and we tend to keep the same things for long periods of time. Like many writers, I stare out the window into my yard when I am trying to come up with something good to say. I think of my grandparents who spent forty years in a house, looking out a kitchen window to a small yard and alley. Would they have noticed a small two-inch rock in the garden that was removed? Would I notice if the lawn timbers were moved a few inches one way or another? Why didn’t Dr. Kroger, for instance, who likely logged many more hours looking out into the courtyard, notice the misplaced rock?

Why

does Monk see the misplaced rock? And why

don’t we see it? The much-studied phenomenon of

selective attention illustrates how we selectively ignore visual data that contradicts our normal experience. Selective attention underlines how we often fail to pay attention to the “corners” of our experience. For example, Levin and Simons discovered in a 1997 study that most people failed notice the change of an actor in a film. When an actor (not a famous one) was replaced by another actor (again not famous but also not similar in appearance to the original actor) who continued to play the same role, most people didn’t notice the change had been made. It seems as long as we get that the actor is the “boyfriend” or “evil genius” we will not pay attention to the switch.

11 When we read about studies like this, we’re sure that

we would notice the switch, but many of us really don’t!

Imagine you’re standing in a public area and an interviewer approaches you and asks you innocently if you would answer a few questions. Agreeing, you start responding. After a few minutes, a couple of workmen walk between you and the interviewer carrying a large door. Following the briefest of pauses to allow the door to move past you, the interviewer politely finishes the survey and thanks you. What is difficult to believe is that most people will

not notice that when that door was passed in between, the interviewer was switched with a different person.

12 We find such experiments disturbing—most of us think we really do see what is happening right in front of us! Test subjects are incredulous when they are told what happened but laughingly accept it when shown a video of themselves in the test situation.

In one of the funniest selective attention studies, subjects are asked to watch a short film with a number of people in white and black shirts passing a ball back and forth between each other. Typically, the “test” is to count the number of times the ball is passed. Intent on counting, most test subjects do not see a person in a gorilla suit, or a girl with a parasol, walk on screen.

13 (You can see examples of these tests on YouTube by searching for “visual attention test.”) What will surprise you, having now read about these studies and being prepared, is that it seems

impossible to not notice the gorilla-suit clad person, but most test subjects really don’t.

Why is there this curious “blindness” in our attention? It’s because what we “see” is more than what is visually in front of us. We don’t just “take in” what appears to our senses and then decide what it means. What we see is very much influenced by what we expect, both consciously and unconsciously. In selective attention studies, we find that we tend to not be aware of changes that do not seem possible. The French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty said that “The normal person

reckons with the possible, which thus, without shifting from its position as a possibility, acquires a sort of actuality.”

14 We think that we are blank slates, and when we have a new experience, we are open to whatever appears to us. But actually, we come to even innocuous experiences with baggage. We exclude data that doesn’t make sense. It is just weird to imagine an actor changing mid-role, and so we ignore that data. It’s nonsensical for people in gorilla suits to be walking around. We tend to ignore the non sequitur because it’s not a real, living possibility for us.

If I enter into a room spoiling for a fight with my husband, I will certainly find one. If I venture into the world, assuming there is, or is not, a divine hand behind it, I will surely be confirmed in my assumption. If Captain Stottlemeyer enters the crime scene in “Mr. Monk and the Very, Very Old Man” assuming a 115-year-old man could not have been murdered, he will not be open to the possibility that a homicide occurred. The studies in selective attention tell us not just that our opinions and cultural heritage can influence how we interpret the world, but also that we have a psychological predisposition to ignore some elements of our perception and register others. But in order to be a great detective we must follow Sherlock Holmes’s prescription that “It is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognize, out of a number of facts, which are incidental and which are vital.”

15

Unless I’m Wrong, which, You Know, I’m Not ...

In Edgar Allen Poe’s story The Purloined Letter, a letter that contains scandalous information about a French royal personage has been stolen. The police are aware of who took the letter and even know where it is. However, despite exhaustive searches of the apartment with every means of technical and professional skill, they cannot find the letter. After hearing this tale from the prefect of police, C. Auguste Dupin, the celebrated investigator of the story, concludes that the letter isn’t hidden there, but must instead be there in plain sight and, under the guise of visiting the thief, finds the letter in open view. Dupin points out to his unnamed narrator that the police are unable to find the letter not because it is hidden from view, but because they can only see the world from their perspectives. They can only search under the supposition that something important would be hidden from view because they would hide such an important letter. They cannot distance themselves from their prejudices about what a criminal “should” do.

In crime scene after crime scene, Monk enters into a room crowded with other experts but, like Dupin, he perceives the clues that slip by everyone else. Monk’s talent is characteristic of any great detective: he sees what others pass over. Monk’s uncanny perceptual talents provide the tools to crack the case, but often the ability for these talents to shine requires a constant management of Monk’s extraordinary distractibility. Dirt, real or imagined, ordinary disorder, and any suggestion of asymmetry, all take Monk’s mind away from the task at hand. Indeed, Monk often seems more occupied with restoring clean order to his environment than with helping to solve a homicide. Only due to the constant chiding of Sharona, Natalie, and Stottlemeyer is Monk able to solve the crime.

Would Monk’s crime-solving abilities be stronger without his obsessive-compulsive tendencies? They are closely intertwined, or perhaps one and the same: Monk is distracted by things that we would likely ignore, but it is because he is distracted by so many seemingly inconsequential things that he notices incongruous elements that solve the cases. Monk really does perceive (not just see, but perceive) more than the rest of us.

The show Monk invites us to try and look both more closely and more broadly; to free ourselves from our own tendency to focus on what we think is present and relevant, rather than what is actually in front of us. Examples like the selective attention experiments show that we sometimes ignore big changes that are right in front of us. We “zone out” when traveling in a car, and when pressed with a question such as “Did we pass Main Street?” we’re unable to say. Or alternatively, when we’re in a tedious meeting, we might be unable to recall what has just been said even if we can hear the speaker quite clearly. In phenomenology, we call this the “natural attitude.”

Phenomenology is a tradition in philosophy guided by the investigations of the German philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), who wanted to start with everyday, natural experience instead of abstract, philosophical theories. This focus on experiences, such as these experiences of selective attention, helps explain why most people are both conscious and not conscious of what they see and hear, just like the prefect of police in The Purloined Letter, or someone not paying attention to a boring speaker, or the driver who does not remember where she has just been. Phenomenologists try and set aside how we think things are, and what we think we experience, by taking up a “phenomenological attitude.” In the phenomenological attitude, we approach the situation as unencumbered by preconceptions, perceptual or conceptual, and try to see things as they immediately and actually appear. When I zone out driving to work, I am thinking about something other than driving and thus my perception has faded into the background. In the phenomenological attitude, I want to be aware of all aspects of my experience not just those that seem the most important or catch my attention.

The phenomenological attitude does not replace the natural attitude. Zoning out in a boring meeting is surely a survival skill, not just a habit. Monk’s life demonstrates the consequence of being unable to leave the phenomenological attitude and return to the natural one. When Monk remains unable to distance himself from the commonplace disorganization we encounter, his inability to leave the phenomenological attitude is both impractical and pathological. His powers of perception come at a price: he is unable to “turn off” seeing dirt and disorder and he is incapable of shutting down the endless stream of his own neurotic thoughts. His colleagues find this seeing and caring about the mundane disorder of the immediate situation annoying and distracting. Because Monk sees everything, hears everything, he is both a surprising genius and a pathological obsessive.

What Really Happened

Monk would see the change in selective attention studies; he would notice the new interviewer or new actor and puzzle over the incongruity. Monk’s cognitive wiring is such that he is constantly being drawn to things that the rest of us pass over without notice. But how do those of us without his talents make sure to not fall into habitual ways of seeing—or not seeing, as the case may be? Phenomenology’s answer to the philosophical problem of how to separate out truth from predispositions, expectations, cultural assumptions, and perceptual errors is to start out by not worrying about the truth at all. Instead, start by providing a careful description of what you experience and “bracket,” or put to the side, any concerns with what should be true or what you expect to be true.

The father of phenomenology, Husserl, called upon us to return to what we experience more carefully, to what he calls going “back to the things themselves.”

16 Phenomenologists make explicit what normally remains hidden from conscious awareness, because we are blinded to change or overly influenced by our cultural opinions. Phenomenologists strive to move from the “natural” attitude to the “phenomenological” one. In the natural attitude, we are like the other characters in

Monk, in the phenomenological attitude we perceive the crime scene as Monk does. Our instinctive tendency is to stay in the natural attitude and not examine our opinions, beliefs, and habits that shape how we perceive others and the world around us.

In religious or political beliefs, we often find people who hold views opposite to ours to be stubborn and unreflective because they think they know the truth. We find those who cling so stubbornly to their “clearly false opinions” to be very frustrating. People tend to strongly defend their own views by excluding ones that disagree with them. We often accept only data that confirm our culturally-trained views, and exclude data that contradict them. As George Carlin once asked, regarding how each of us reflexively fails to understand the views of others as potentially valid, “Have you ever noticed that everyone who drives slower than you is an idiot and everyone who drives faster is a maniac?”

When we speak to someone who is very closed-minded, we have the impression of never being able to break that person’s foolish self-certainty. How can this ignorant person not see how wrong she is!? But we can also ask the other side of that question. Why is anyone “open-minded”? Why do philosophy at all? Philosophy asks us to be uncertain, to ask lots of questions that don’t have obvious answers. It ruins our previous ideas and is cruel enough to not always replace them with comforting alternatives. The path of an open-minded person is not necessarily a happy one. Why not just stay in the natural attitude with our prejudices and beliefs that make us content? If ignorant, prejudicial beliefs help support a sense of self-satisfaction and have deep cultural and psychological roots, why would anyone want to call them into question? Phenomenology argues that the experience of the “foreign” causes us to leave the natural attitude and move toward the philosophical. For example, I can’t help but question my own religious belief when I meet a reasonable intelligent person with a different one. This causes me to turn back on my own beliefs and see them as beliefs instead of as facts.

While religious and political views provide the ground for heated philosophical debates, the move to a phenomenological attitude can also be the simple experience of understanding that others do not see the world as I do. My first philosophical experience was when I was five. I had a pair of Charlie Brown snow overshoes. On the toes of the boots, the left had written “Good” and the right, “Grief.” I remember standing in the snow, realizing that if I wasn’t me, standing staring down at my toes, but was standing in front of me toe-to-toe, “Good Grief” would be upside down and I couldn’t read it. While of course my thoughts about the matter were pretty minimal, it did provide a brief glance that my world is a world for me. I have a perspective. My world is not necessarily everyone else’s world. I can only perceive my world; I cannot perceive the world.

At first this seems worrisome, since it is often the case—as with political views, for instance—that perspective seems to be the problem. It seems that if we could “get outside” our perspectives and really see the truth, we would find true knowledge. An absolute faith in the sciences, or scientism, holds a similar view. What is really true is something that will not permit a point-of-view; it would be something that would see something from all sides, all possibilities, at once. Phenomenology argues that this is based in the supposition that truth must be somehow without a perspective (or “objective”). It argues that a careful examination of our experience shows us that we have no reason to believe this.

Zen Sherlock Holmes Thing

When noticing a small change, Monk is struck by the way it is an unharmonious fit within a larger landscape—a disruption. But Monk does not, as one would in the natural attitude, assume that certain disruptions are more or less relevant. He brackets out the value-laden idea of what should and shouldn’t be significant.

The murder that precipitates each episode is the most obvious of disruptions in the characters’ lives. The supporting characters focus on the murder. If it is the police, such as Stottlemeyer and Disher, they try to solve the homicide. If it is the criminals, they are concerned with covering it up. What makes Monk different is that he gives attention to seemingly unimportant details in the room and in the victim’s life. He has bracketed out any ideas about what the murder should mean and sees the situation for what it really is.

In “Mr. Monk and the Garbage Strike,” Monk is able to start solving the case by realizing that the union boss could not have possibly have killed himself because the wing-back of his chair would have limited the movement of his right arm, and, in addition, why would a suicide victim wipe off the prints from his bullets? The solution often hinges on Monk’s ability to put himself in the position of either the criminal or the victim. To say that the most truthful view would be to have no point-of-view would mean Monk could not perceive the strangeness of the alleged suicide.

We cannot understand human experience without understanding human partiality and perspective, thus a God’s eye “scientific” view from nowhere could never explain how we always approach a situation from somewhere. In the phenomenological attitude we are asked to bracket our beliefs, or to put aside our preconceived ideas, habits, and beliefs, and examine what experience really teaches us. Monk shows us a phenomenological viewing of the crime scene—as Sharona calls it in the first episode Monk’s “Zen Sherlock Holmes thing”—in his use of his hands to “frame” what he is looking at while slowly walking around the room. He is taking in the entire scene, including the perspectives of the perpetrator and the victim. Monk is in the phenomenological attitude when he considers both the chair of the union boss as well as how the union boss would have acted in that chair. Stottlemeyer stays in the natural attitude since he can only see what he, Stottlemeyer, finds normal and natural. Monk is able to realize that the scene has different perspectives.

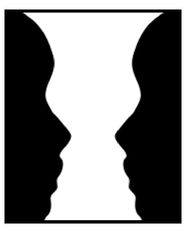

In our natural attitude, much of our experience is largely passive and unconscious except for the object of our attention. I don’t think about all the various things in the yard—the rocks, the grass, the trees—when I am looking at a bird at the bird feeder. I am fully aware only of the bird. In order to engage in phenomenology, I have to make a conscious decision to not depend upon my unconscious and habitual beliefs, even those about the nature of the material world (Husserl, Ideas, §27). In Gestalt psychology, which deeply influenced and was influenced by phenomenology, we refer to the figure-background aspect of our perception. When one looks at a common optical illusion what is striking is that the same visual data produces two different perceptions that cannot be reconciled.

Take the above common optical illusion: either you see a vase or you see two faces, but you cannot see both at once even though the image does not change. Optical illusions present these kinds of either-or scenarios because our minds cannot find an “interpretation”—the image has no context, no supporting background to tell you if it is two faces or a vase. If a body was drawn attached to each face, the strength of the vase image would disappear. In perceptions that do not immediately challenge us, such as the perception of a room, we find that we tend to fixate on certain objects—the television screen, our dog, the painting—and do not pay attention to the other parts of the room. The rock Monk sees, Dr. Kroger also sees, but for Dr. Kroger it remains in the background, whereas Monk draws the background to his conscious awareness.

What is unusual about Monk is his ability to seemingly give equal cognitive weight to all aspects of what he experiences and to not give priority to the “obvious” object of focus. He engages in the phenomenological attitude in his “Zen Sherlock Holmes thing” by seeing what is really present rather than what we are predisposed to believe or ignore. In “Mr. Monk Goes to a Fashion Show,” Monk finds out that the suspect cannot read English and questions how someone illiterate in English would have known to not use the door with a sign notifying that it will trigger an alarm if opened. What stumps Stottlemeyer and Disher in these cases isn’t that they don’t have access to the same sensory data as Monk, but that they can’t seem to “perceive” its relevance. Monk notices how a criminal would have seen the situation; he would have read the sign unthinkingly and not used the door even though the fire escape was closest to the murder. The murderer’s use of the English language was just background for him—he was busy thinking of the alarm as a problem, and never thought that his demonstration of English-language competence would be what would bring him down in the end.

No Exit from the Phenomenological Attitude

In “Mr. Monk and the Garbage Strike,” Monk knows that the “suicide” is actually a murder, but lies about this in an attempt to end the strike that so disturbs his obsessive need for cleanliness. His disorder might open his eyes to clues that remain unbeknownst to others, but it ties him to them, not letting him distance himself from the immediate givens of his world. As we are constantly reminded in the show, Monk’s abilities are also his “curse.” Despite the value of being able to focus on all the details of a scene, from the smallest of rocks to the most obvious of emergency exits, Monk’s curious talents have a dark side.

For one, it is extremely unpleasant to talk to a philosopher, or a police consultant, who cannot help but be skeptical about every undefended claim and fault. Socrates was finally prosecuted for this irritating quality of not permitting those with influence to pass off their opinions as knowledge. Even though a phenomenologist strives to capture in a description of experience what often goes unnoticed, most exit phenomenology when getting up from the desk. While it is frustrating to the subjects in selective attention studies to be later shown that they ignored a very obvious change in their perception (by showing them a video of their interview, for instance), this ability to not have to be aware of every change is what allows us to be normal and functional. It would be impossible to hold down much of a job if every time one noticed a small amount of dirt one was driven to distraction until it was cleaned.

The only way Monk can work is to have a full-time assistant at his beck and call 24/7. Monk presents us with an example of what a phenomenologist might be like if she were never able to leave the phenomenological attitude and return to the natural one. If we were trapped as careful observers of our experience, never able to return to the rest of habitual opinions and selective attention, we would drive ourselves and others to insanity.

The opening credits of the first show (“Mr. Monk and the Candidate”) show Monk talking to himself during his obsessive getting-ready rituals (his socks in Ziploc baggies, brushing his teeth, hanging clothes) as if he were speaking to Dr. Kroger. In his monologue, Monk says familiar pop psychology types of affirmations “you can’t sweat the small stuff” and “I’m going with the flow.” He knows he suffers from his peculiar perceptive abilities and knows if he could only stop “sweating the small stuff” or ignoring everything he experiences, he would be happier.

In certain episodes, Monk’s disorders cause him to have partial or complete breakdowns that require the assistance of his therapist, Dr. Kroger or later Dr. Bell. In the first season (“Mr. Monk Goes to the Asylum”), Monk is committed to a psychiatric hospital after he shows up at Trudy’s old house, unaware of his behavior. While committed, the psychiatrist, Dr. Lancaster points out that Monk might be using his surprising analytical powers as props to hide his problems. Although it turns out that Dr. Lancaster is guilty of murder and imprisons Monk, Monk says almost ruefully when the doctor is arrested that “except for the murders and you trying to kill me, you really were the best doctor I’ve ever had.”

Dr. Lancaster’s interpretation is that Monk uses his “gift” to not have to form close relationships with others. Certainly his compulsions often ruin moments of normal human interaction—he is unable to focus on conversations if his hands feel dirty or something is out of place, and in “Mr. Monk and the Marathon Man,” his badly-timed use of a wipe leads to several people assuming he is a bigot. Monk’s sex life is non-existent since Trudy’s death, a theme that receives a fair amount of attention in some episodes. Monk is even unable to discuss their past sex life much less have a sex life. In “Mr. Monk and the Paperboy,” Dr. Kroger says, “Adrian, we can talk about your sex life with Trudy or we can sing show tunes until this session is over. It’s your choice.” It is then that we discover that Mr. Monk appears to be a fan of the classic Lerner and Loewe musical, Camelot.

These biographical stories provide us with a clue into an aspect of Monk’s own limited perspective of his own life, despite his extraordinary openness to not being predetermined in his analysis of a crime. He’s unable to integrate the importance of emotion in his own life and this makes him unable to enjoy the company of others. The neurologist Antonio Damasio’s compelling book, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (Penguin, 2005), explores patients with brain damage that compromises their ability to feel emotion. Such patients do not, as we might expect, find themselves in a Spock-like world where they are able to conduct themselves in a purposeful rational manner. Instead, they are strongly unable to function successfully in the world because they are unable to choose what is relevant and what is not in a situation. They have no perspective, no vantage point. At work, for instance, they will occupy themselves for hours with a relatively unimportant task instead of prioritizing the more significant tasks first. Maurice Merleau-Ponty also discusses such cases of brain damage in his Phenomenology of Perception, in particular the case of Schneider, whose injury caused a host of disabilities, including an inability to properly structure the world through empathic connections to others. Schneider is curiously unable to have any kind of ambitions or plans that would normally guide someone’s life even though his intelligence is undamaged.

The “error” of Descartes that Damasio discusses, and Merleau-Ponty explores phenomenologically, is the misconception that reason provides us with the most authoritative structuring of our world and experience. Emotion, it has been long argued, leads us away from the truth because it tends to persuade us to think, do, and believe the wrong thing. But, we find that a person without an emotional compass cannot engage with the world in a meaningful, purposeful manner. Everyday tasks are almost insurmountable, interpersonal exchanges mysterious and frustrating. Damasio and Merleau-Ponty point out that reason isn’t sufficient to provide us with a true knowledge of the world because it takes an “objective” stance that removes the narration we need in our lives. Reason by itself can only give us a world of sensory data without coherence or meaning.

Monk is able to perceive the emotional structuring behind the criminal’s motive for homicide, but he refuses to allow emotional connections to structure his own life (except in the direst cases when he must overcome his disorder to save his friends’ lives). Thus, Monk could possibly remain even closer to his phenomenological attitude if he would bracket his insistence on structuring the world according to phobias and rules of tidiness and instead be open to the way in which emotion plays a role in his life. Monk should be careful not to fall into his natural attitude of seeing emotional connections as “distractions.” But it remains questionable whether such a move would make Monk a better detective, even if would make him a happier man.

It’s a Gift ... and a Curse

Is the curse the price of the gift? On the one hand, without his disabling obsessions, Monk could better see how his own life is structured by background emotional bonds. Yet, on the other, it seems that his talents come from his inability to leave the phenomenological attitude and return to the habitual, natural one. Monk complains in “Mr. Monk and the Other Woman” that “It doesn’t make any sense” to which Stottlemeyer replies, “Does everything have to make sense, Monk?” For us, everything does not need to make sense. Most people are not constantly troubled by incongruous change, uneven books, and inconsistent behavior. In order to allow for the background of emotional connections that shape our experience to come to light, we have to allow others elements to return to the background. I cannot form a bond with a friend if I cannot stop thinking about the dirt on her shoes. I must allow the dirty shoes to recede from my awareness and concentrate on what she is telling me. But Monk seems unable to let the sensory background fade and let the emotional one come forward.

Monk’s characteristic reply to Stottlemeyer’s question, “Does everything have to make sense?”, is “Well ... yeah, it kinda does.” The price he is afraid to pay for the loss of “sense” is the loss of his perceptive abilities. Even though Monk suffers from his disorder, he is in a bind: given his guiding ambition is to become a police officer again, he cannot lose too much of the “curse” or he will lose his unique talents. In the tradition of great private investigators and detectives of print and film, the road of genius is a solitary one where the gifts that solve cases isolate and exclude one from the illogical, emotional, and habitual lives of others. Monk’s phenomenological perception marks him as different for better and for worse. As in Poe’s poem, ever since his childhood, Monk has encountered a world that is different from our own:

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were; I have not seen

As others saw; I could not bring

My passions from a common spring.

(EDGAR ALLEN POE, “Alone,” 1829)