Maxentius in Rome – Adventus Constantini – The Arch of Constantine – Meanwhile: Licinius and Maximinus Daia – Constantine confronts Licinius

At the end of 2006, archaeologists announced a most remarkable discovery on Rome’s Palatine Hill: the insignia of a Roman emperor, hitherto known only from descriptions and depictions on coins, had been unearthed. A sceptre, in the form of a flower clasping a blue-green ball, and three additional glass and chalcedony spheres were found wrapped in silk within wooden boxes. Alongside them were four javelins, three lances and a base for planting standards (figs. 28 and 29). These had been buried, it was conjectured, to prevent them falling into the hands of the owner’s vanquisher. In this way, one small part of Maxentius’ imperial legacy survived his defeat by Constantine. All else was rapidly swept up in a process of revision and rebranding: damnatio memoriae, which erased the memory of the emperor now called only ‘tyrant’.

Maxentius in Rome

When Constantine entered Rome, he saw a city that had been altered substantially in Maxentius’ short reign. The city’s defensive walls had been supplied within living memory by Aurelian, but they were repaired and heightened and the gates strengthened to withstand sieges set by Severus and Galerius. Structures within the walls were built anew in areas devastated by fire in 283, and outside the walls a new imperial complex was completed adjacent to the Appian Way, between its second and third milestones in the region called ad catacumbas, after its Christian catacombs. Diocletian and Maximian had not neglected Rome, which remained a centre of symbolic importance for the empire and a unifying feature in Tetrarchic ideology. Nor did the Tetrarchs neglect the damaged fabric of the city, as one later source, the anonymous Latin Calendar of 354, records:

Many public works were erected by these emperors: the senate house, the Forum of Caesar, the Basilica Julia, the Theatre of Pompey, porticoes II, nymphaea III, temples II [to] Isis and Serapis, the New Arch and the Baths of Diocletian.

However, as the names make clear, all but the last of these were reconstructions. The erection of the Baths of Diocletian was the only major new project, aimed at securing the favour of the urban unwashed. They were begun by Maximian on his first recorded visit to the city, in 298–9, when he was returning from campaigns in Africa, but they were not completed until 305–6, as is revealed by an inscription recording their dedication to the two retired Augusti, two reigning Augusti and two Caesars. In the meantime, in 303, Diocletian had also made his first recorded visit to Rome, to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of his accession. This was the reason for the construction of the second new structure, the New Arch, a triumphal arch spanning the city’s Via Lata. But when the old Augustus left the city prematurely and intent on reforms, Maxentius was thrust to the fore by the Praetorian Guard, jealous of their privileges. Maxentius needed a broader support base and achieved it through grand public building campaigns.

Maxentius’ building projects represented a conscious revival of Rome’s status as an imperial capital and reminded citizens of their place at the heart of the empire: an empire divided and supplied in recent years with a number of competing imperial cities. We have explored Constantine’s Trier, an imperial centre of recent development to rival Diocletian’s Nicomedia and Galerius’ Salonica. To this list one must add Maximian’s preferred residence at Milan, and two other cities favoured by Diocletian: Sirmium on the Danube, while he was actively campaigning, and Split on the Dalmatian coast in retirement. Each city served as a centre of administration, with an imperial court at its heart. Maxentius emulated these developments, creating a new imperial complex on the Appian Way. An imperial villa, of fairly modest proportions, served as the residence and reception halls. From the villa a covered path ran to the new circus, giving Maxentius direct access to a box overlooking the 10,000 seats. This complex, more than anything within the city’s walls, demonstrated his commitment to Rome. An inscription of 311–12 discovered there announces that Maxentius was an ‘unconquered emperor’, invictus augustus. But he was also then the father to a recently departed son, whom he had divinized and buried in the family mausoleum, a rotunda facing the villa. Two inscriptions discovered in 1825 at the circus commemorate the son, who had been named for this family and, perhaps not entirely fortuitously, after the founder of Rome. His name was Valerius Romulus.

The need to site this mausoleum outside the pomerium, the formal boundary of the city, has been suggested as the reason for locating the entire complex outside the city’s defensive walls, where so recently imperial rivals had encamped. The mausoleum was depicted on coins that Maxentius minted after Romulus’ death, which projected a new image for himself and the Valerian dynasty (gens Valeriana). For the first time these coins bore the names and images of the Tetrarchs, but only those who had recently died, and only those who had been related to Maxentius by blood or marriage. Constantine (Maxentius’ brother-in-law by his marriage to Fausta, and very much alive), Licinius and Maximinus were ignored. The relationship between the dead and the living was spelt out on the coins: ‘to the divine Romulus son of Maxentius Augustus’ and ‘to the divine Maximian father of Maxentius Augustus’. More contentiously, following Galerius’ death in May 311, Maxentius struck coins to him addressed by his formal name, Maximian Junior: ‘to the divine Maximian father-in-law (socer) of Maxentius Augustus’. Most provocative were the coins ‘to the divine Constantius, kinsman ( cognatus) of Maxentius Augustus’, which claimed Constantine’s own father for the Valerii. The obverse of these coins featured a bust of Maxentius below the phrase AETERNAE MEMORIAE, ‘to the eternal memory’. Constantine was suitably provoked.

Within the city Maxentius erected buildings that projected the deep roots planted by his chosen family, the gens Valeriana, in Rome’s soil. His location of choice was the Velia, a low ridge that projects from the northern side of the Palatine. One of the seven hills on which Rome was founded, it was associated in legend with the most famous of the Valerians, P. Valerius Publicola, one of the first consuls. Rather conveniently, the Temple of the City that adorned the Velia was destroyed in a fire in 306, allowing Maxentius to erect a huge basilica, eighty metres long, twenty-five wide and thirty-five tall. Its shell may still be seen, although on signs one must seek the Basilica of Constantine for reasons that will be explored shortly. Even more impressive was the Temple of Roma and Venus erected beside the Velia, between Maxentius’ basilica and the Flavian amphitheatre (the Colosseum). Dedicated by Hadrian in AD 135, the temple had been damaged in the fire of 283, and again in 306. Maxentius’ reconstruction was the largest temple in Rome and the largest devoted to the goddess Roma ever to be constructed. On the side of the basilica away from this temple, at the foot of the Velia, was erected a far smaller sanctuary, but one with greater personal meaning, for it may have been constructed atop the ancestral tomb of the Valerii. Maxentius dedicated this temple to his dead son Romulus and his namesake.

Together these buildings comprised the Forum of Maxentius, which with his imperial complex on the Appian Way illuminated Maxentius’ dedication to the city and its history. This message was disseminated also by his officials. An inscription on a marble plinth was raised by Furius Octavianus, keeper of the sacred buildings of Rome, on 21 April, probably late in Maxentius’ reign. The date is Rome’s birthday, the natalis urbis, and the plinth was discovered near the Lapis Niger, traditionally regarded as the tomb of the original Romulus. It reads:

To Unconquered Mars, Father, and to the founders of his eternal city. Our Lord Imperator Maxentius Pius Felix, Unconquered Augustus [dedicated this statue].

On top was once found a statue, possibly of Mars but perhaps of his sons, the founders of the eternal city, Romulus and Remus. It has even been suggested that the Lupa Capitolina, the majestic bronze in the Capitoline Museums of the she-wolf suckling those infants, once sat atop this plinth, although there are also claims that Maxentius relocated that sculpture to the Lateran, where it was attested through the Middle Ages (fig. 30).* A base has been found there with four depressions exactly aligned with the feet of the wolf. The parallels between Maxentius and Mars are clear: both are fathers of the city and, more literally, of sons named Romulus; both are unconquered. Constantine’s arrival ended the reign of Mars and Maxentius.

Adventus Constantini

Constantine’s victory required the eradication of Maxentius’ legacy. This was achieved by traditional Roman means: damnatio memoriae, damning Maxentius’ memory and appropriation of his legacy. The most common label attached to Maxentius was ‘tyrant’, the worst type of leader. In the city of Rome the term was redolent of the rhetoric of the killers of Julius Caesar, and still earlier of the champions of the Republic who had despatched the reges superbi, those kings bloated with pride who had oppressed Rome. In this latter context, one must note the remarkable coincidence between the phrase ‘by divine instigation’ (instinctu divinitatis) found in the inscription on the Arch of Constantine and the suggestion that the proud king Tarquin was driven out ‘by instigation of the gods’ (instinctu deorum, where gods are certainly plural). Nazarius, who in 321 delivered a panegyric in praise of Constantine, spoke of the ‘loathsome head of the tyrant’ paraded through Rome and then despatched to Africa, so that the crowds in Carthage might also witness Constantine’s victory. Charged with such an edifying task, even the winter winds co-operated, speeding the ship south across the Mediterranean with its grisly cargo. ‘Tyrant’ alone would suffice in future to identify Maxentius, as we shall see on the dedicatory inscription attached to Constantine’s arch. The Calendar of 354 states simply of the year 312: ‘The tyrant was cast out.’

Before Nazarius, the anonymous orator of 313, whom we met at length in the previous chapter, provides details of Constantine’s adventus, his entry into Rome after the defeat of Maxentius. Constantine’s first act was to recover Maxentius’ body from the Tiber, for the citizens had to know that their emperor was truly dead:

The swirling river rolled along the bodies and arms of other enemies and carried them away, but that one it held in the same place where it had killed him, lest the Roman people should long be in doubt whether it was to be believed that the man, the confirmation of whose death was sought, had actually escaped … Then after the body had been found and hacked up, the whole populace of Rome broke out in vengeful rejoicing, and throughout the whole city where it was carried affixed to a spear that sinful head did not cease to suffer disfiguration.

It has often been noted by those wishing to add a Christian twist to Constantine’s actions that no mention is made by the orator of a visit to the temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline, the established terminus of a triumphal procession. The author of the panegyric knew and borrowed from an earlier oration in praise of Maximian, delivered in 307, which makes specific mention of Capitoline Jupiter, but he failed to incorporate these details. However, no weight can be placed on this argument from silence, for no account of a ceremonial act can be read as a plain record of what happened and why. Rather, the retelling of ritual serves a purpose in itself, as Philippe Buc has advised historians of medieval Europe: to establish the superiority of one account and the interests of its author. Similar insights inform Mary Beard’s recent study of the Roman triumph, which offers commentary on the procession under scrutiny.

Constantine’s procession appears to have been a formal triumphus, a rare and carefully staged celebration of specific military victories that was voted for the emperor by the senate. Although instances had increased during the later third century, between 31 BC and AD 235 only thirteen formal triumphs were staged in Rome for nine generals, with four holding more than one. Augustus staged three on three successive days, folding his civil wars into foreign victories. His actions reflected distaste for the formal celebration of victories in civil wars, and that this remained the case is demonstrated by Septimius Severus’ refusal of a triumph in 195 lest it appear to be for victory in a civil war. Severus subsequently failed properly to celebrate his great victories over foreign foes, perhaps because of gout, which meant he could not stand during the processions associated with the dedication of his triumphal arch in Rome.

Constantine may have had similar scruples about staging a formal triumphus to celebrate victory in a civil war, although his return to Rome in 315 suggests that he, like Augustus, would gladly fold domestic successes into those over foreign ‘barbarians’. In 312 there was simply no time to stage such an event – gathering prisoners and booty to display, decking the city in banners and flowers, arranging groups along the route to shout acclamations, and much more besides – between the battle on 28 October and the imperial entry into Rome on the very next day. One cannot assume from the fact that crowds cheered Constantine that Maxentius had been universally unpopular. A victorious general riding at the head of a long line of battle-hardened, largely Gallic and German troops might convince many to hoot encouragingly. Nor need we trust the orator of 313 in his portrayal of Maxentius, ‘that monster’ who had dispensed Rome’s treasures ‘to gangs of men hired to rob citizens … and while he enjoyed the majesty of that city which he had taken, he filled all of Italy with thugs hired for every sort of villainy’. One wonders whether the orator is referring here to Maxentius’ loyal soldiers, who fought Constantine across the north of Italy, or his tax-collectors. The damning of Maxentius’ memory was well advanced by 313, so every clichéd atrocity is attributed to him. A sustained comparison between Constantine and Maxentius illustrates the point:

He was Maximian’s illegitimate changeling (suppositus), you the true son of Constantius Pius; he was of a contemptibly small stature, twisted and slack in limb, his very name mutilated by a misapplied appellation, you (it suffices to say) are in size and form what you are [the audience could see the emperor] … you were attended by respect for your father, but he, not to begrudge him his false paternity, by disrespect; you were attended by clemency, he by cruelty; you by virtue devoted to a single spouse, he by lust befouled with every kind of shameful act; you by divine direction, he by superstitious mischief; he, finally, by guilt for the despoiled temples, the slaughtered senate, the Roman plebs destroyed by famine, you by thanks for the abolition of calumnies, the prohibition of delation (delatio), the avoidance of shedding even murderers’ blood.

The most striking accusation here is that Maxentius was not Maximian’s true son, but rather was a suppositus, someone introduced into the family falsely, not truly of the gens Valeriana. A rumour had been started that Eutropia, Maxentius’ mother, had conceived him by a Syrian, perhaps even a dwarf. Small wonder that he shared none of Constantine’s chaste Roman qualities and dabbled in magic rather than trusting in true divinity. This is rather comical, given that so recently Constantine had invented for himself an imperial lineage, projecting an entirely false descent from Claudius II. Indeed, it would appear likely that the reason such emphasis was placed on Maxentius’ illegitimacy is that similar stress had recently been placed on Constantine’s birth by Helena, who upon Constantine’s accession was not Constantius’ widow, if she ever had been his wife.

The final list of Constantine’s merciful concessions suggests that he was actively courting the plebs by dismissing court cases and freeing criminals. He is portrayed as cancelling Maxentius’ aberrant methods of policing, and it is stated that false accusations would no longer be heard, but nor would those that might be true, for delatio means ‘the giving of information against someone in order to have that person’s crimes come to the notice of the proper authorities’. There arose from this the tradition that Maxentius had persecuted the senate and that Constantine had freed one hundred senators from fetters, all of whom joined his joyous parade. Thus, in 321, the rhetor Nazarius claimed of the adventus: ‘Leaders in chains were not driven before the [emperor’s] chariot, but the nobility marched along, freed at last. Captive foreigners did not adorn that entrance, but Rome was now free.’ And just as those whom Maxentius was alleged to have oppressed were liberated, so were his enforcers dismissed. The Praetorian Guard, by whose intrigues he had come to power, whose support had allowed him to vanquish his father, and who had fought beside him at the Milvian Bridge, was disbanded. Constantine was able to achieve what Diocletian and Galerius could not, and dispensed with that overpaid and dangerous corps. He similarly abolished the equites singulares, the emperor’s horse-guard, razing their camp on the Caelian Hill and in its place erecting a new building, a grand basilica that adjoined the Sessorian Palace, where Constantine based himself while in Rome and which he gave to his mother Helena in 326, upon determining to settle permanently elsewhere. The new building was a basilica, rather similar to the one he had constructed in Trier, which later became a church. And this new basilica also became a rather famous church, St John in Lateran, seat of the bishops of Rome before the construction of St Peter’s. This gift was accompanied by a host of rich furnishings including, according to the (far later) Book of Pontiffs, ‘a silver paten weighing twenty pounds … a golden chalice weighing two pounds. Five service chalices each weighing two pounds … twelve bronze candlestick chandeliers each weighing thirty pounds’. The weight of the items was a measure of their value, and hence of the esteem in which Constantine held their recipient, the bishop of Rome.

The equites singulares had remained loyal to Maxentius throughout his reign, and his end was their end. Consequently, Constantine damned their memory as he did that of his rival. It is remarkable that all of Constantine’s Christian buildings in Rome were connected in some way with their destruction or that of the Praetorian Guard. Not only did St John in Lateran replace the camp of the horse-guard, but a church dedicated to St Marcellinus and to St Peter, two Christians martyred in Rome, was constructed at the site of their unit’s graveyard, at the Via Labicana, and this was associated with a mausoleum in which Constantine planned for his own mortal remains to be interred. It would come instead to house his mother’s. The Praetorians fared little better: their cemetery on the Via Nomentana was replaced with a church dedicated to St Agnes and St Constantius, also local martyrs. It is hard indeed not to reach the conclusion that Constantine wished to assert that his victory over the Praetorians and the horse-guard was achieved through the power of the god of the Christians, but we cannot say whether he wished this immediately, in 312, or somewhat later, as we do not know the exact dates at which the churches were founded. We do not know these dates, but we do know that Constantine’s were not the first imperial churches in Rome. Maxentius had already sponsored a building dedicated to St Crisogonus in Trastevere. This information was later suppressed, so that all would equate Constantine’s victory with that of Christianity.

Damning the memory of Maxentius has made the task of identifying his building projects most difficult, as they were the easiest to appropriate. They were raised in such a short period as to have no distinctive style, and certainly not one distinct from that attributed to Constantine. In the words of Aurelius Victor, ‘All the works that [Maxentius] had built with such magnificence, the Temple of the City and the basilica, were dedicated by the senate to the merits of Flavius [i.e. Constantine]’. Constantine discontinued use of Maxentius’ circus on the Appian Way and enticed the crowds back to the Circus Maximus by adding new rows of seats. The tragic collapse of a decade before, during Diocletian’s vicennalia festivities, would in any event have commended repairs. A bust identified as either Constantius Chlorus or Claudius Gothicus has been found within Maxentius’ villa, and the fact that one cannot distinguish between the two possible honorands seems only to support the point that Constantine was seeking to make: the Valerians had given way to the Flavians. The Valerians were no longer. Nowhere is this clearer than on coins Constantine had struck in Rome modelled closely on those struck by Maxentius to honour his divinized relatives, including Constantine’s father. Just as fortunes were reversed, so is the commemorative inscription, now MEMORIAE AETERNAE. The image of the Valerian mausoleum was removed and replaced by an eagle of consecration or the Herculean lion or club, and the images are of Claudius Gothicus, Constantius and Maximian.

The buildings on the Velia were similarly rededicated to the scion of the Flavian house. An inscription at the Temple of Romulus reads: ‘[Dedicated] to Flavius Constantinus Maximus triumphant Augustus, by the senate and people of Rome.’ The Basilica of Maxentius became the Basilica of Constantine, and the conqueror still more literally took on the parts of Maxentius, for within the tall basilican apse stood a colossal statue of its founder. This was taken and the head reworked to resemble Constantine. Several colossal body parts, including the famous head, were found in 1486 within the basilica and can now be seen a short distance from there in the courtyard of the Capitoline Museums (fig. 31). The oversized eyes have always attracted attention, and fourth-century viewers, unlike today’s, believed that they projected beams, thus both surveying and possessing the buildings he had appropriated. This statue is referred to by Eusebius in his Ecclesiastical History (HE), who added further that ‘perceiving that his aid was from God, he immediately commanded that a trophy of the Saviour’s be put in the hand of his own statue’. Eusebius continues (HE IX.9.11):

And when he had placed it, with the saving sign of the cross in its right hand, in the most public place in Rome, he commanded that the following inscription should be engraved upon it in the Roman tongue: ‘By this saving sign, the true proof of valour, I have liberated your city freed from the yoke of the tyrant and moreover, having set at liberty both the senate and the people of Rome, I have restored them to their ancient distinction and splendour.’

Eusebius revised his account and expanded it greatly in a later work, the Life of Constantine.* But both accounts of the statue and the ‘saving sign’ post-date 325, when Constantine felt quite differently about his victory. A second colossal statue reveals more clearly Constantine’s initial feelings upon entering the city of Rome in 312 and again in 315. The Colossus was made for Nero, and its head was his on the body of the Sun god. It had been altered several times over the centuries, most recently to resemble Maxentius’ dead son Romulus. This much is revealed by an inscription which adorned its base and which was incorporated into a further structure, one most likely raised for Maxentius but now rededicated to Constantine: the famous Arch of Constantine.

The Arch of Constantine

In July 315 the senate celebrated Constantine’s victory and decennalia together, in stone, by dedicating a triumphal arch in Rome and offering vota - prayers of thanks for his continued rule (fig. 32). Recent excavations suggest that the arch, like the basilica and temples that had been recently rededicated to Constantine, had been erected for Maxentius. The arch is placed at the endpoint of his building project, and as one approached it, its archway framed the colossal statue of Nero/Romulus/ Sol. The most recent head, of Romulus, was replaced with that of Constantine. It has been suggested that this very head is the bronze in the Capitoline Museums, and indeed it has suitable attachments. However, the hair and eyes seem more in keeping with Constantine’s later image, forged after 324 (fig. 47).

One might ask why, in 312, Maxentius was constructing a triumphal arch, for surely he had neither the time during Constantine’s rapid march south, nor indeed the hubris to anticipate a victory so brazenly. It seems more likely that the monument was an element of the general triumphal ideology within which Maxentius presented himself as the ‘Unconquered Prince’, whose divine companion was Mars Invictus. Had he not driven off two imperial rivals, Severus and Galerius, who had marched on Rome? And had his expeditionary force not delivered Africa from the pretender Domitius Alexander? Still, one might wonder at the timing of the arch’s construction, as it stood virtually complete in 312. Perhaps the best explanation is that the ludi saeculares, the secular games, were scheduled to be celebrated in 314. The secular games were held in Rome to mark the start of each new saeculum, a period of 110 years. Although Philip the Arab (b. AD 204) had staged millennial games in the city in 248, to celebrate the thousandth anniversary of the city’s foundation, there had been no secular games since those under Septimius Severus in 204. The centrepiece of Severus’ celebrations had been the triumphal arch completed in 203 to mark his victories over the Parthians, amongst others. Maxentius’ ostentatious romanitas made the celebration of the games inevitable, and the precedent of the Arch of Severus, the architectural model for the new Arch of Maxentius, would appear to confirm the association between recent victories, planned festivities and construction.

Maxentius had his arch decorated with sculptures taken from earlier monuments. This saved the time and expense of carving new panels, and there may well have been much available to plunder, following the fires of 293 and 306, particularly from the Hadrianic monuments on the Velia. All Maxentius’ projects at this site reused second-century materials. Furthermore, Maxentius had the recent example of Diocletian’s New Arch, erected just a decade before, which employed reliefs from a Claudian or Antonine structure (now to be seen at the Boboli Gardens in Florence). In the form that it can be seen today, the monument can be considered nothing other than the Arch of Constantine. However, if one posits Maxentius’ own inspiration for many of the choices, the arch’s overall scheme becomes comprehensible, for many reliefs do not display triumphal imagery, but rather showcase generic imperial qualities. They were chosen to remind Rome’s citizens of the city’s constant renewal and the centrality of the figure of the emperor to that renewal, for once again an emperor was resident among them. Moreover, the sculptures placed Maxentius in the line of succession from great emperors of the past, notably Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius.

The upper register of the arch consists of eight relief panels taken from an existing monument, possibly a triumphal arch, erected in honour of Marcus Aurelius by his son Commodus. In four panels above the lateral archways, either side of the central inscription, on the south face, we see: the appointment of a foreign king, rex datus, reflecting the emperor’s universal dominion; his adlocutio, or speech to the troops, emphasizing concord, concordia; the lustratio ritual before the military standards, illustrating piety, pietas; and the presentation of barbarian prisoners, again beneath the standards, where the emperor might exhibit clemency, clementia. On the north face we see: the emperor’s adventus, the arrival in Rome, representing felicitas, and the consequent triumph overseen by Victoria, who flies above with a laurel crown; his profectio, the departure on campaign which symbolizes his virtus, manly valour; the emperor’s distributions and largesse, reinforcing the quality of liberalitas, generosity (fig. 33); and finally a second scene depicting the submission of the vanquished, beneath four standards (fig. 33). As the panels are spolia - material carved earlier for another purpose and then collected for reuse by Maxentius - one might understand the emphasis on traditional Roman imperial virtues and actions. Maxentius did not wish to become Marcus Aurelius, but rather to highlight the qualities of the great second-century emperor that he shared. That Constantine retained these demonstrates that the scenes also suited his needs, but his appropriation of the arch as a monument to his victories required that the heads be re-cut with his own features. The heads on the figures one sees today were replaced in 1732 during restoration work ordered by Pope Clement XII.

Eight tondi, round sculpted panels, from a Hadrianic monument occupy the arch’s middle register, flanking the central archway and surmounting the side archways on the north and south sides of the monument. On the southern face of the arch, the emperor and his comrades gather before an archway, probably a gateway, suggesting that they are just outside the city. To ensure success, in the next panel they sacrifice to Silvanus, god of the woods. They proceed to a bear hunt in panel three, where the mounted emperor is shown with spear raised, ready to strike (fig. 34). On the fourth roundel, the last on the south face, a sacrifice of thanks is offered to Diana, goddess of the hunt (fig. 34). On the arch’s north face, the first of four tondi depicts the emperor mounted once again, in the act of running down a boar. Next, a sacrifice to Apollo is the best-preserved image of an imperial figure and his two companions, the second to the right holding the reins of a horse. In the third panel a lion has been killed, and the hunters stand over their trophy. Finally, an emperor appears veiled, sacrificing to Hercules. For Maxentius, the scenes may simply have displayed the prowess and piety of his predecessor, Hadrian, while engaged in the most imperial of pursuits, the wild beast hunt. However, all of these scenes might be interpreted metaphorically, as victories over diverse barbarian peoples represented by the various beasts. This was surely Constantine’s preferred interpretation. His re-cut features have survived in at least some of these scenes, as have those of a second imperial figure who appears in five scenes and was once believed to be Licinius. Scholars of this persuasion posited a secondary message: Constantine and Licinius are at peace, and Dyarchy, the rule of two emperors, has supplanted Tetrarchy, the rule of four. This was possible, for the two men were bound to each other from 311. However, the second figure has now been identified as Constantine’s father, Constantius Chlorus, and thus the scenes serve to demonstrate the piety of the imperial gens Flavia. It is Constantius, not Constantine, who is shown sacrificing. Moreover, only in these sculptures are all the imperial figures shown nimbate, with haloes. This invites the possibility that these heads were re-cut, once again, before Constantine’s visit to Rome in 326, for by then he had foresworn participation in sacrifice and was regularly depicted nimbate. We shall return to these themes later.

Four panels from a monument of Trajan, known commonly as the Great Trajanic Frieze, feature on the inner walls of the central archway and on the eastern and western sides of the uppermost register. In each of the frieze panels Trajan’s head has been replaced by Constantine’s. On one side of the central passage Trajan as Constantine sits astride his horse in the mêlée of battle, his cloak flying above his left shoulder. As he tramples on one barbarian, his right hand is raised to strike down another. The eagle-bearer is a pace behind him, indicating that he is at the front of the battle line. Only one legionary precedes him. Battle scenes on the eastern and western sides of the arch fill out the action. On the second panel in the central archway, Trajan as Constantine is crowned by Victory and greeted by Virtus, a divine figure representing his ‘manly valour’ whose features are remarkably similar to those of the goddess Roma.

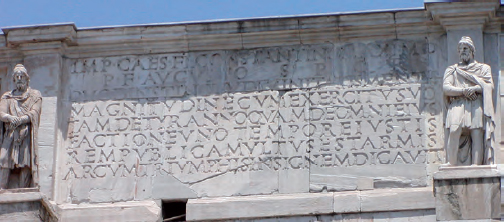

The separation and largely out-of-sight placement of these four panels, the most elegant and most clearly martial of the reused elements, suggests that they may have been chosen by Constantine and fitted where space allowed between Maxentian elements. One might also suggest that Constantine chose the eight free-standing barbarians, Trajan’s Dacian captives, which stand atop each of the arch’s columns (fig. 33). The fourth-century elements of the arch that can be ascribed with certainty to Constantine’s initiative are: the frieze which depicts his campaign of 312; the inscriptions, still clearly visible on either side of the archway, offering thanks for his ten years as emperor (votis X) and prayers that he will reign for twenty (votis XX); the arch-spandrels and pedestals; and the dedicatory inscriptions (fig. 35) on both north and south faces that read:

TO EMPEROR FLAVIUS CONSTANTINUS MAXIMUS FATHER OF THE FATHERLAND, THE SENATE AND ROMAN PEOPLE, BECAUSE WITH DIVINE INSTIGATION AND THE MIGHT OF HIS INTELLIGENCE, TOGETHER WITH HIS ARMY HE TOOK REVENGE BY JUST ARMS ON THE TYRANT AND HIS FOLLOWING AT ONE AND THE SAME TIME, HAVE DEDICATED THIS ARCH MADE PROUD BY TRIUMPHS

The god is identified in Latin by a singular form: this was the summus deus, the greatest god and divine patron working through Constantine’s intelligence and the might of his army. It was the theology of victory in action. The identity of this singular god is implied by a sculpted tondo, which depicts Sol on his quadriga (four-horsed chariot) rising out of the ocean, and by its pair, which shows the moon descending on a two-horsed chariot, a biga. The Luna (Moon) tondo is immediately above the start of the narrative sequence, Constantine’s departure from Milan, on the arch’s western side, while the Sol tondo surmounts its denouement on the eastern side, Constantine’s ceremonial entrance (adventus) into Rome (fig. 36). Between these, on the southern face of the arch, are portrayals of the siege of Verona and the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (fig. 34). On the northern face are shown the triumphal celebrations in Rome, with Constantine delivering a speech and distributing largesse. The goddess Victoria is Constantine’s constant companion. At the siege of Verona she hovers behind to crown him. At the Milvian Bridge, Constantine’s image (now destroyed) was depicted flanked by the goddesses Roma and Victory. As he enters the city of Rome, the reins of the horses pulling Constantine’s quadriga are held by Victory. Similarly, on the fourth-century arch-spandrels and pedestals, symbols of victory are omnipresent. On the pedestals placed either side of the main archway Victories, trophies and soldiers stand over defeated enemies. In spandrels framing the main archway to both north and south, Victories are depicted carrying trophies. These would all have appeared entirely appropriate to Constantine, representing the Roman theology of victory as he understood it.

A gilded bronze statue of Constantine atop his own quadriga, no longer in place, surmounted the arch above the central inscription. It was a further indication of the identity of the singular divinity and his correspondence with Constantine. Even more striking, but until recently overlooked, was the alignment of the arch, placed slightly off the triumphal way (via triumphalis), with the colossal statue of Nero now sculpted anew to bear the face of Constantine and the radiate crown of Sol Invictus. The alignment one can attribute to Maxentius, who must have pictured his divinized son appearing framed by this new triumphal arch. With both appropriated by Constantine, the statue would have appeared to the emperor and his processing troops at various points on his triumphal journey to the Forum behind the arch. Initially, its head would have framed his own gilded statue atop the arch. As the emperor moved closer, to around thirty-five metres from the arch, Sol would have been framed by the archway. Drawing still closer, the statue would have become indistinct until Constantine emerged through the archway, when Sol would have appeared to him suddenly, echoing the story of his vision as disseminated in 310.

It has been argued that the predominantly pagan senate was responsible for this monument, and the deities portrayed announced its understanding of Constantine’s vision and his divine patron. The dedication is theirs, in the dative, as are the inscriptions above the Trajanic panels in the central passageway, ‘to the liberator of the city’ and ‘to the establisher of peace’. But to insist on a senatorial reading contrary to Constantine’s own understanding is to ignore the correspondences between the arch and the range of coinage Constantine produced, which disseminated a clear message: Sol Invictus was the guarantor of Constantine’s victory. For five years before the arch was dedicated, Sol had appeared on Constantine’s gold, silver and bronze coins and was the central element of Constantinian propaganda directed at all levels of Roman society. Most frequently, Constantine issued coins modelled on those of his claimed forebears Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian, which featured on their reverses an image of Sol Invictus as his ‘companion’ (comes). These coins were dedicated SOLI INVICTO COMITI, ‘to the Invincible Sun, preserver of the Augustus’. On coins where Sol is not thus invoked on the reverse, Constantine himself is frequently featured on the obverse wearing a radiate crown - a crown from which project spikes or triangles representing solar rays (fig. 37). In 313 a gold coin struck for Constantine by his mint at Ticinum shows on its obverse the emperor and Sol Invictus together. The bust of Constantine wearing a laurel wreath is superimposed over the bust of Sol, identical but for his radiate crown. Sol’s profile is visible behind the emperor’s, at his right shoulder as they both face left. The resemblance between the emperor and the god recalls the panegyric of 310, where Constantine is reminded ‘You did see the god, and recognized yourself in the likeness of him’. To complete the picture, Constantine holds a shield on which Sol’s quadriga is shown rising from the ocean. The reverse depicts Constantine’s triumphal entry into Rome. The inscription on the obverse hails Constantine as invictus. A remarkably similar image was used later on gold medallions minted at Ticinum in 315-16, although on these Constantine held an orb in his left hand, not a shield (fig. 38). Evidently, Constantine resembled his patron god in every way.

Meanwhile: Licinius and Maximinus Daia

In February 313, Constantine and Licinius met in Milan. Two years earlier, confronted with an alliance between Maxentius and Maximinus Daia, Licinius had agreed to marry Constantine’s younger half-sister, Constantia. At Milan the wedding was celebrated, and the emperors cemented their agreement by issuing a famous joint letter commanding universal religious toleration, known commonly as the Edict of Milan. Versions of its text have been preserved in both Eusebius’ Ecclesiastical History and Lactantius’ On the Deaths of the Persecutors; the latter, the more complete and accurate, begins:

When I, Constantine Augustus, and I, Licinius Augustus, happily met at Milan and had under consideration all matters which concerned the public good and security, we thought that among all the other things that would profit men generally that which merited our first and chief attention was reverence for the divinity. Our purpose is to grant both to the Christians and to all others the freedom to follow whichever religion they might wish; whereby whatsoever divinity dwells in heaven may be appeased and made propitious towards all who have been set under our power.

At the time of the pronouncement Constantine had already eliminated his western rivals, but Licinius had still to deal with his eastern foe, Maximinus Daia. The principal account, completed by Lactantius before 315, is fascinating in portraying Licinius as Constantine’s fellow champion. Eusebius, in contrast, would amend his first account of Licinius, preserved in his Ecclesiastical History, adding a chapter to its final book (HE X.8) to vilify the emperor for his reversal. He would later portray Licinius as the foil to the hero of his Life of Constantine and omit mention of his role at Milan (VC I.41.3). But for both Eusebius and Lactantius, the greater villain is Maximinus Daia. Already established as worse even than his sponsor Galerius, Maximinus was swept back into the spotlight by resisting Galerius’ dying wish that the persecution of Christians be ended. It was against him, then, that the Edict of Milan was directed, and Lactantius reminds us that Licinius’ task was to ensure that Maximinus complied.

Having received Galerius’ instruction to repeal the persecution in 311, Maximinus Daia had acted cautiously. While Galerius still lived, he moderated his actions. Whereas Constantine and Licinius had set about releasing Christians condemned to the empire’s gaols and mines, and restoring property that had been seized from them, Maximinus instructed his subordinates no longer actively to pursue Christians, but to take care not to publicize the edict of toleration. Following Galerius’ death, Maximinus was no longer checked, and responded enthusiastically to appeals for a renewed persecution in the vast lands under his control, which stretched from the Asian shore of the Bosphorus to Antioch and beyond. Indeed, it was claimed that he solicited such petitions, including one preserved as an inscription at Arycanda in Lycia, in what is today southern Turkey. This was addressed to him and to Constantine and Licinius:

The gods, your kinsmen, most illustrious emperors, having always shown manifest acts of kindness to all who have their religion earnestly to heart and pray to them for your perpetual health, our invincible lords, we have thought it well to have recourse to your immortal sovereignty and to request that the Christians, who have long been disloyal and still persist in the same mischievous intent, should at last be put down and not be suffered by any absurd novelty to offend against the honour due to the gods.

In the further reaches of his realm, the bishops of Emesa (modern Homs in Syria) and Alexandria were both beheaded, and the Christian scholar Lucian of Antioch was brought to Nicomedia, where Maximinus condemned him to death. Such cruelty came naturally to the morally depraved ruler, Lactantius noted, supplying a long rhetorical diatribe that dwelt on Maximinus’ sexual depravities, which prefigure a myth of the high Middle Ages, the droit de seigneur (or droit de cuissage), the right to deflower local virgins.

As Constantine prepared to meet Maxentius before the walls of Rome, according to Eusebius (HE IX.8), Maximinus was making war on the Armenians, who were ‘from a very early date friends and allies of Rome, a Christian people and zealous adherents of the Deity’. In fact, Maximinus was in Syria and nowhere near the Armenians, who converted some years later, under their king Tiridates. By the time Constantine and Licinius convened at Milan, Maximinus was back in Nicomedia, having marched his army west in the depths of winter, leaving the corpses of pack animals along the route. On short rest his troops pressed on to Byzantium, a city on the European shore of the Bosphorus (see map 5). Licinius had left a garrison in Byzantium, which Maximinus attempted first to win over with bribes and then to displace by force. The garrison resisted for eleven days - long enough to send word to Licinius, who hurried east. Maximinus, meanwhile, sailed across the Bosphorus into Europe, meeting resistance from another of Licinius’ garrisons at Heraclia in Thrace (ancient Perinthos, modern Marmara Ereğli). As Maximinus’ force, numbering 70,000 men, proceeded north-west, Licinius and his army of 30,000 had reached a staging post eighteen miles beyond Adrianople. According to Lactantius, ‘As the armies approached each other, it seemed that a battle would shortly take place. Maximinus then made a vow to Jupiter that, if he won the victory, he would obliterate and utterly destroy the Christian name.’ Licinius, in turn, on the eve of battle with Maximinus, had a divine vision to rival Constantine’s. This he translated into a means to galvanize his troops to battle. In a dream an angel appeared before Licinius and ‘told him to rise quickly and pray to the supreme god with all his army; the victory would be his if he did this’. Thoughtfully, the angel provided the words of the prayer:

Supreme God, we beseech you; holy God, we beseech you. We commend all justice to you, we commend our safety to you, we commend our empire to you. Through you we live, through you we emerge victorious and fortunate. Supreme, holy God, hear our prayers, we stretch our arms to you; listen, holy, supreme God.

Lactantius notes further that: ‘This [prayer] was written out and distributed to the officers and tribunes, so that they could all teach them to their own troops. Confidence grew among them all with the belief that victory had been announced to them from heaven.’ Suitably neutral with regard to which supreme god was being worshipped, the prayer appeared acceptable to all, and the troops intoned it three times on their knees on the field of battle, before engaging and defeating Maximinus’ forces.

Such a sympathetic account of Licinius’ progress was excised from later accounts. Eusebius, in the revised version of his Ecclesiastical History (HE IX.10), quite naturally attributed Licinius’ victory to the Christian god’s favour, but he made no mention of the vision or prayer. It seems most likely that Constantine and Licinius had composed the prayer together, in Milan, and perhaps also contrived the notion that a divine or angelic visitation would be the natural medium for such words to be revealed to an emperor. Thus, the troops of the Dyarchy were obliged to acknowledge a singular highest god, the same god as had brought Constantine to supreme power in the west and would allow Licinius to attain similar authority in the east. But we must beware of following Lactantius and Eusebius uncritically in identifying Licinius’ patron god as the Christian divinity, for a contemporary work of art suggests Sol Invictus was still at large.

A cameo in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris, which is generally believed to portray Licinius celebrating his victory of 313, shows an emperor on a four-horsed chariot or quadriga advancing over the bodies of the vanquished, holding a globe in his left hand and a spear in his right (fig. 39). Personifications of the sun and moon present globes, and two Victories flank his chariot, one bearing a vexillum (flag standard), the other a tropaeum (trophy). Recently the cameo had been re-dated to the later fifth century, but Martin Henig has related it to a second cameo of the early fourth century and highlights similarities between the two. The latter, an agate cameo, depicts a youthful clean-shaven ruler in a style typical of the Tetrarchy, wearing an imperial diadem. He holds in his left hand a sceptre which rests on his shoulder, and in his outstretched right hand a globe. He faces forwards standing in a moving quadriga, his cloak (paludamentum) billowing behind him and his four horses rearing on their hind legs. The scene closely resembles contemporary portrayals of Sol’s chariot, and that association is made certain by the scene depicted on a golden plaque in the Hermitage in St Petersburg, which was manufactured in AD 60-70 to adorn a priest’s crown (fig. 40). This shows Nero as Sol astride a quadriga drawn by rearing, galloping horses. His cloak billows behind him, to his left, and in his outstretched right hand he holds a staff or wand, perhaps a whip. He wears a radiate crown and stares forwards, above his head a sickle moon and star-shaped sun. Henig has suggested that the agate cameo was produced to mark Licinius’s victory over Maximinus. Here, then, we find Licinius portrayed as Constantine’s counterpart, his victory over Maximinus equated with the defeat of Maxentius, both attributed publicly to Sol Invictus.

Constantine confronts Licinius

Following his victory at the battle on 30 April 313, Licinius made for Nicomedia. There he repealed Maximinus’ persecution and on 13 June had erected for all to see an inscribed version of the letter he and Constantine had formulated in Milan. He instructed that copies of the letter be despatched to all cities and towns in the eastern realm and that they be displayed prominently attached to rulings by local magistrates, so that the will of the emperors would no longer be suppressed. Maximinus, who had fled the battlefield, was pursued to Tarsus, where he committed suicide. Lactantius invented a suitable denouement: the poison Maximinus ingested failed because he was so engorged with food and wine, leaving the man deranged for four days; in that time, he pounded his head so hard against a rock that his eyes popped out, allowing him finally to see the true god. While attesting to his conversion, Lactantius fails to corroborate Eusebius’ claim that Maximinus also issued an edict recanting his anti-Christian ordinances. Both stories seem rather unlikely.

Having rejoiced in the painful deaths of the persecutors, both Lactantius and Eusebius recount rather dispassionately that Licinius cleaned house. Statues of Maximinus, like Maxentius branded ‘tyrant’, were cast down throughout the empire. His wife, his eight-year-old son and his seven-year-old daughter were all put to death at Antioch. So were other potential rivals: Valeria, daughter of Diocletian and Galerius’ widow, was murdered; her mother Prisca and her adopted son, Candidianus, met the same fate. Candidianus had been betrothed to Maximinus’ young daughter. Severianus, son of the ephemeral Augustus Severus, was executed. Now, only two imperial families remained, that of Licinius and that of Constantine, united through Constantia who, in 315, produced a son, Valerius Licinianus Licinius. Licinius’ hopes and claims for his son immediately became an issue between the emperors.

Since his marriage to Fausta in 307, when she was still a child, Constantine had not produced a second son. Initially, one imagines, he did not attempt to consummate the marriage, but by 316 Fausta was perhaps eighteen years old, and it may have appeared that she was barren. Constantine moved, therefore, to ensure the succession of Crispus, his only son (by Minverina), who was by now twelve or thirteen. Still too young properly to play a role in administering the empire, Crispus was to become a Caesar alongside a second man, Bassianus, a Roman senator who was certainly old enough to govern. While Licinius was married to Constantia, one of Constantine’s three half-sisters, Bassianus was married to another, Anastasia. This wedding had most likely taken place during Constantine’s sojourn in Rome from July to the end of September 315. Bassianus was, therefore, brother-in-law to both Augusti and was to be entrusted with Italy, including Rome.

The status of Italy, and more particularly of Rome, had been a bone of contention between the Augusti. Constantine’s acquisition of Rome in 312, and with it the whole of Italy, had violated Licinius’ interests. Licinius, the older Augustus, had been named senior ruler of the west at the council of Carnuntum in November 308 and charged with the duty of removing the usurper Maxentius. This formal reconstitution of the second Tetrarchy had recognized Constantine’s right only to the title Caesar, but from 310 to 312 he had proceeded to usurp both the title and the role assigned to Licinius, as well as the patron god of the late Galerius, Sol Invictus. Neither of the Augusti resided in Rome: Constantine shuttled between Arles and Trier in Gaul, while Licinius established his court at Sirmium in Pannonia. But both coveted Rome, and the arch erected there by the senate for Constantine was a monumental poke in Licinius’ eye. Rome continued to laud Constantine.

On coins minted in Rome in 315 to mark the start of his decennalia, Constantine was exalted with the invocation ‘To the Happy Victory of the Eternal Prince’ (VICTORIAE LAETAE PRINC PERP). One must imagine that this reflects an actual acclamation offered by his troops during the victory celebrations. No coins celebrating Constantine’s decennalia were minted in lands under Licinius’ control, nor are there any surviving inscriptions that mark the occasion. This indicates strongly that relations between the two men had soured considerably since 313. Perhaps Bassianus’ promotion was to remove Italy from the purview of either Augustus and so bring them closer together. More likely it was a ploy to disinherit Licinianus, promoting an alternative imperial line which Licinius was sure to reject and providing Constantine with a casus belli and the support of Bassianus. But there was an unexpected twist, for in the winter of 315-16 it became apparent that Constantine would have a second child after all. On 7 August 316, in Arles, a son was born whom he named Constantine. One tradition holds that Fausta was not the mother, and this led to rather confused coverage in later sources, notably Zosimus in the sixth century, some two hundred years later. However, Julian the Apostate, Constantine’s nephew, who was hostile to his uncle and his sons, would claim that Fausta was mother to three emperors.

What happened early in 316, and indeed immediately after the birth of the young Constantine, is obscured by Constantine the father’s later propaganda, but it is clear that Bassianus had ceased to be an asset, becoming instead a threat to the succession of Constantine’s offspring. Licinius discerned this, and according to the Origo Constantini persuaded Bassianus to do his bidding:

Through the influence of Senicio, Bassianus’ brother who was loyal to Licinius, Bassianus took up arms against Constantine. He was seized while still preparing himself, and at Constantine’s order was convicted and executed. When Senicio, as the person responsible for the plot, was demanded for punishment, Licinius refused to hand him over, and the peace between them was broken.

Constantine got his casus belli, at Bassianus’ expense. While we cannot be certain that Licinius did persuade Bassianus to rebel, or indeed that Bassianus even took up arms (for Constantine had invented a similar story to justify his murder of Maximian), there is no indication that Licinius was unhappy with the outcome. He ordered statues of Constantine to be thrown to the ground at Emona (modern Ljubljana in Slovenia), which sat on the frontier between their two realms, and thus declared war.

In October 316 and again in January 317 the armies of the two Augusti met in battle (see map 5). Constantine’s forces appear to have won the first encounter at Cibalae (modern Vinkovci), between the rivers Drava and Sava, but the second clash on the Arda plain, south-east of Sardica, was less clear-cut and equally indecisive. The account offered by the Origo Constantini seems almost balanced:

Both their armies were taken to the plain of Cibalae. Licinius had 35,000 men, infantry and cavalry; Constantine commanded 20,000 foot and horse. After an indecisive battle, in which 20,000 of Licinius’ infantry and part of his armoured cavalry were killed, Licinius escaped under cover of darkness to Sirmium with the greater part of his horse. From there, having collected his wife and son and his treasury, he went to Dacia. He made Valens, commander of the frontier, a Caesar. Then, when a huge force had been gathered by Valens at Adrianople, he sent ambassadors to Constantine, who had established himself at Philippopolis,* to discuss peace. The ambassadors returned frustrated, and having resumed war they fought again on the plain of Arda. After a long and indecisive battle, Licinius’ men gave way and fled in the darkness. Licinius and Valens turned away towards Berroea, believing (which was true) that Constantine would pursue them by heading further towards Byzantium. So when Constantine was forging ahead eagerly, he learnt that Licinius was at his rear. Just then, when his soldiers were weary with battle and the forced march, Mestrianus was sent to him as an ambassador to sue for peace, at the request of Licinius who promised henceforth to do as he was told. Valens was commanded to return to his former rank, and when this was done peace was confirmed between the two emperors, and Licinius held the provinces of Oriens, Asia, Thrace, Lesser Moesia and Scythia.

This meant that Constantine had acquired the rest of the Balkan lands west of Thrace, a significant addition to his holdings encompassing the region of his birth, Moesia and Pannonia, and all of Greece. This was a substantial concession and suggests that Licinius’ forces were as depleted as the Origo’s (exaggerated) figures propose. Zosimus (II.18-19) claims that the fighting was particularly brutal and supplies similarly high figures. A further later source, Peter the Patrician, suggests that Licinius’ ruse, turning aside to Berroea rather than heading straight to Byzantium,

Had allowed him to capture much of Constantine’s retinue and baggage train, and this may have forced Constantine’s hand, preventing him from pressing a third battle. The demotion of Valens was less of a concession from Licinius, who later saw that he was murdered. Caesars were clearly now expendable, mere pawns in the end game of the Augusti. Unless, that is, they were the sons of the Augusti.

At Sardica on 1 March 317, the peace was sealed by the promotion of the sons of the Augusti, all three at once, to the rank of Caesar. Constantine was recognized unequivocally as senior Augustus and established his new capital at Sardica. He resided there for much of the next seven years, while his sons were sent back to Gaul, Crispus presiding at court in Trier. Licinius withdrew further east, establishing his court at Nicomedia, formerly home to Diocletian, Galerius and, most recently, Maximinus Daia. The emperors continued to mint coins in each other’s names, and one finds Licinius portrayed on coins with Constantine’s patron Sol on the reverses, and Constantine with Licinius’ patron Jupiter. However, neither emperor was satisfied with joint rule, and the battle for supremacy would soon be rejoined. That war, unlike in 316-17, would be pitched as a clash between their patron deities, for by then Constantine was openly a Christian.

21. Detail from the Arch of Galerius, showing the Tetrarchs sacrificing at an altar on which are depicted Jupiter and Hercules. (Author)

22. Detail from the Arch of Galerius, showing the shield-badge of a soldier in a Herculian legion. (Author)

23. The columns of the Tetrarchs, erected in the Forum in Rome, here shown in relief on the Arch of Constantine in Rome, eastern end of the northern facade. (Author)

24. Constantine’s Basilica (Basilika) at Trier, exterior view. The reception hall was shortly afterwards converted into a church. The current structure has been rebuilt. (Author)

25. Woman with pearls, often identified as Helena. Detail from one panel of the ceiling paintings from a site identified as a bed-chamber in the imperial residence at Trier. (R. Schneider/Bischöfliches Dom- und Diözesanmuseum Trier)

26. The Eagle Cameo, also called the Ada Cameo, preserved in Trier’s Stadtbibliothek. (Stadtbibliothek Trier MS 22 Ada-Evangeliar)

27. A green glass beaker depicting shield designs, kept in Cologne’s Römisch-Germanisches Museum. (Römisch-Germanisches Museum zu Köln)

28. The imperial insignia of Maxentius: the tops of ceremonial lances unearthed during excavations on Rome’s Palatine Hill. (Reproduced from Jean-Jacques Aillagon, ed., Roma e i barbari, Milan 2008)

29. The imperial insignia of Maxentius: glass spheres unearthed during excavations on Rome’s Palatine Hill. (Reproduced from Jean-Jacques Aillagon, ed., Roma e i barbari, Milan 2008)

30. The Lupa Capitolina, the bronze in Rome’s Capitoline Museums of the she-wolf suckling Romulus and Remus, recently identified as a medieval copy. (Author)

31. Parts of a colossal statue of Constantine, now to be found in Rome’s Capitoline Museums. (Author)

32. Arch of Constantine, southern facade, Rome. (Author)

33. Upper-register panels from the Arch of Constantine, northern facade, depicting the emperor’s distributions and largesse, and the submission of the vanquished beneath four standards. The panels are from the reign of Marcus Aurelius, while the free-standing barbarians to either side are Trajanic. (Author)

34. Two Hadrianic tondi on the Arch of Constantine, southern facade, depicting a bear-hunt, where the mounted emperor is shown with spear raised, and a sacrifice of thanks to Diana, goddess of the hunt. Below is a Constantinian frieze depicting the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Above is the inscription Sic XX, a prayer for the emperor to reign for twenty years. (Author)

35. Dedicatory inscription on the Arch of Constantine. (Author)

36. The eastern side of the Arch of Constantine. In the centre there is a tondo depicting Sol ascending in a quadriga above a relief of Constantine’s adventus into the city of Rome. (Author)

37. Gold coin showing Constantine wearing a radiate, or solar, crown. (Scala/BPK, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin)

38. Gold medallion, struck at Ticinum in 315-16, depicting Sol and Constantine jugate. Their features are identical, and almost uniquely they are both facing left. A very similar image was first used on a nine-solidus medallion struck at Ticinum in 313. (The Trustees of the British Museum)

39. Cameo of Licinius, now to be found in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. (Bibliothèque nationale, Paris, France/Giraudon/ The Bridgeman Art Library)

40. A golden plaque depicting Nero as Sol, standing upon a quadriga, in the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. (The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)