FUNDAMENTAL to the development of museums in Britain is the idea that they are a reflection of the cultures, and at points classes, that create and curate them. From what was collected to how it was exhibited, Victorian museums large and small were an integral part of wider assumptions about culture and control. From objects appropriated in the furthest reaches of empire to concerns with regional identity and national pride, museums illustrated ideas about order and progress, ownership and control, particularly in light of evolutionary thinking popularised through the latter part of the nineteenth century. While that period saw museums achieve a recognised place in national life, progressing from treasure troves to potentially active forces in local communities, displays tended to portray a clear and uncomplicated ordering of history – with ample interpretation of Britain’s leading role – for the benefit of middle-class audiences. While such themes continued through the twentieth century, the period was undoubtedly dominated by increasing systemisation and specialisation, both in types of institution open to the public and in the practice and perception of their work.

Central to this were changing notions about the role of the museum, particularly evident through developments in education and display in common with William Henry Flower’s ‘New Museum Idea’ for natural history institutions. Although management of collections remained paramount, museums increasingly sought to open their doors to the public, providing new spaces from lecture halls to auditoriums, new wings and extensions accompanied by more proactive, pre-planned educational programmes of activities and events. Chamber music, organ recitals and even theatrical productions became more commonplace and local societies and interest groups, from art to natural history, were encouraged to use museum collections and facilities in their work. Beyond the museum, curators sent out lecturers and loan collections, and organised excursions to local sites of interest where people could study topics in context, and even participate in collecting and excavating work. Classes of elementary-school children were welcomed to larger museums as a matter of rote – in an average week in the early 1950s, staff at Manchester Corporation Art Gallery would accommodate some five hundred schoolchildren while the university-managed Manchester Museum played host to one hundred elementary school classes; special opening hours for visits from children and young people were standard at many institutions from the late nineteenth century.

Palaces of lifelong learning. In this photograph from the 1940s, a schoolgirl uses the collections at the Geffrye Museum of historic interiors in her studies.

This desire to educate and engage audiences also extended to the treatment of collections and displays. Through the first half of the twentieth century, changing exhibitions became customary, both through use of a museum’s own collections and exploitation of loan material that was circulated nationally. The way in which objects were displayed also went through transformation, with greater attention paid to historical context and understanding of simply displayed material, rather than relying on the assumption that visitors were in some way subject specialists who would have the ability to interpret large collections of curios for themselves. More advanced institutions, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, had already started to circumvent the tendency to arrange material according to artistic movements or countries, and establish ‘period rooms’ – utilising original woodwork from historic buildings or reproduction backdrops to provide settings for furniture, paintings and other objects. Likewise many art museums rethought the display of their picture collections, away from works hung in tiers according to size, shape and colour, designed to decorate a palatial space, and towards new techniques such as the hanging in one room, in comparative isolation, of a few selected works. On a larger scale, the growth of collections, including modern works, was seen to necessitate new and separate galleries for their display, such as at the Tate Gallery in London (now Tate Britain), while the National Portrait Galleries of London (1856) and Edinburgh (1882) represented attempts to specialise in portraiture, by gathering many such works together in single venues.

The drive to specialise was not restricted merely to art galleries however, and increasing systemisation in curatorial practice was matched by the development of a number of distinct types of museum focusing on particular collections and themes. National and municipal museums were by now long established phenomena, with the British Museum and the National Museum of Scotland joined finally by the Cardiff-based National Museum of Wales, formally opened by George V in 1927. Local museums were an established feature in most large towns, while university museums in places such as Oxford, Cambridge, Manchester and London had been largely but not solely an outgrowth of Victorian collecting zeal, the demands of academia and generous personal bequests. Through the twentieth century, the number of national museums continued to grow further, reaching a total of fifty-four across the UK in 2012.

Museums are still closely associated with old-fashioned glass cases and displays, seen here at the Royal Mint Museum and in the shark room at the Natural History Museum.

Meanwhile, the wider world of museums had become still more diverse with an array of new types of institution, their establishment driven by numerous factors, scientific, technological, economic, social and specialist – from the eccentric to the sublime. This includes a number of museums dedicated to the military and war: most famously, Imperial War Museums (IWM), a national museum organisation with five sites in England – warship HMS Belfast, historic airfield IWM Duxford, underground wartime command centre the Churchill War Rooms, Salford-based Imperial War Museum North and the original Imperial War Museum in London. The latter was established in 1917 to record the civil and military war effort and sacrifice of Britain and its empire during the First World War, although its remit now covers all conflicts involving British and Commonwealth forces since 1914. Integral to its role is the challenge of interpreting difficult subject matter (sometimes known as ‘hot interpretation’) from the Holocaust to recent politically contentious conflicts such as the Iraq War, a task backed by an extensive sound archive and object, art, film, video, photograph and archival collections. Originally housed at the Crystal Palace at Sydenham Hill, the museum opened to the public in 1920; from 1936 it found a permanent home in the buildings of the Bethlem Royal Hospital, the Southwark institution for treatment of the insane. It survived bombing during the Blitz to become the leading public museum organisation for conflict and war. Likewise focused on the interprelation of war are the National Army Museum, established in 1960, and the Royal Naval Museum at Portsmouth dockyards, as well as by numerous smaller museums and museum galleries dedicated to – and often funded by – individual regiments. The continuing prevalence of military heritage across Britain demonstrates the fundamental need to understand and memorialise the struggles and human cost inherent in war, and arguably more than any other venue reminds us of the larger place of museums, and of history, in the rationalisation and remembrance of certain aspects of the past.

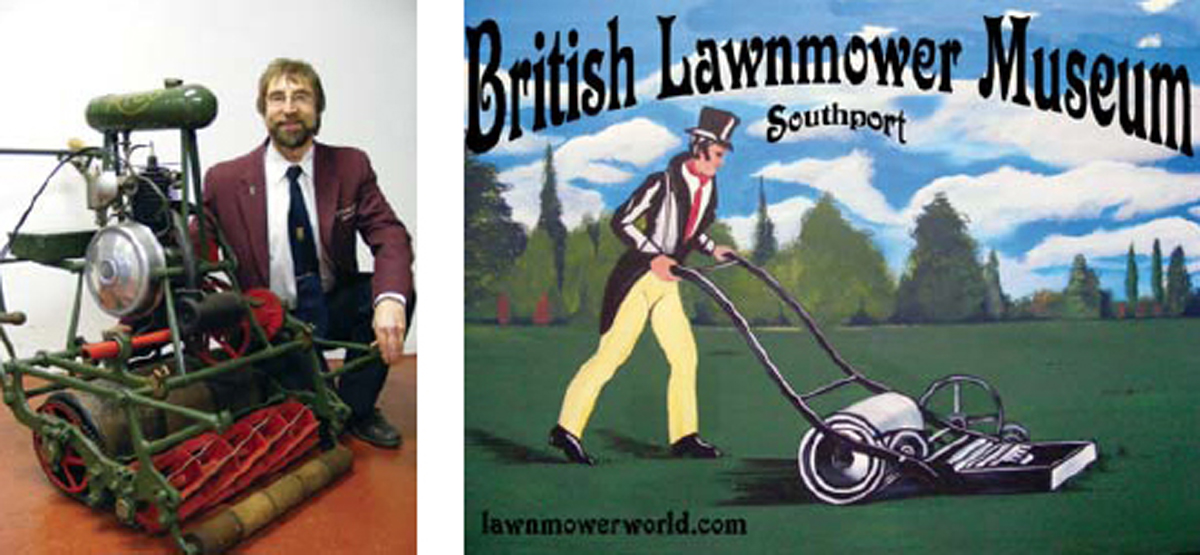

Beyond war, the twentieth century has seen the opening of museums on almost every conceivable topic – from lawnmowers, toys and fans to pencils, Bakelite, baked beans and witchcraft, no subject seems too quirky or obscure. Some of the most intriguing are small independent organisations originally based on the objects owned by a specialist or enthusiast with a desire to spread knowledge about their subject, in some cases people whose personal collections have become so large that creating a public museum has seemed more practical than trying to store and display items in their individual homes. One such example is Robert Opie, founder of London’s Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising, whose collection of wrappings, tins, toiletries, posters and more began with a Munchies packet at Inverness station in 1963, which spurred his lifelong fascination with brands and what other people consider rubbish. Following an exhibition of his collection ‘The Pack Age: Wrapping It Up’ at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1975, Opie established a museum at Gloucester Docks in 1984, and later in London, where the public can see a range of exhibits and displays from Victorian ephemera to a 1980s peach melba Ski yoghurt carton. Together this material shows that ‘rubbish’ takes on a special resonance over time, affording an insight into the way we live, contemporary design and domesticity, as well as challenging ideas about what we collect and why, and what such material can tell us.

Inveterate collector and founder of London’s Museum of Brands, Robert Opie.

Also focused on how we live, on a grander scale, has been the twentieth-century trend towards folk-life and open-air sites. These had their roots in Scandinavia, where several museums featuring re-erected buildings from different places and periods were opened during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, most famously at Skansen in Stockholm. A reaction to industrialisation and its impact on rural lifestyles, folk-life and open-air museums sought to keep alive an understanding of how working – often rural – people lived, particularly through displays of re-erected vernacular architecture and demonstrations of practical, traditional crafts. The approach became popular, particularly in America where a reconstruction of the colonial capital of Virginia, Colonial Williamsburg, was opened in 1926 and Greenfield Village at Dearborn, the first open-air American site along Scandinavian lines, was founded by car manufacturer Henry Ford in 1929 (part of The Henry Ford). For the first British example, one must look to the Welsh Folk Museum at St Fagans, an outgrowth of the National Museum of Wales, opened twenty years later to the west of Cardiff. The site was a gift from the Earl of Plymouth, who offered St Fagan’s Castle and the surrounding estate, now covering 100 acres of woodland and pastures, for the establishment of an open-air museum to tell the story of the people of Wales. Faced with the considerable challenge of capturing and interpreting national identity, the museum now plays home to more than forty original buildings, from a 1760 Powys woollen mill to a set of nineteenth-century ironworkers’ houses from Merthyr Tydfl, besides the castle itself. The re-creation of a historic environment also extends to farming and land management; the museum maintains traditional breeds of livestock and cultivates historically accurate crops through use of traditional techniques.

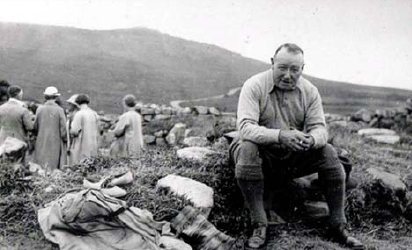

Retired Indian Army officer and amateur archaeologist, Colonel Frederick Hirst, pictured here at one of his digs at Porthmeor, Cornwall c. 1937. Hirst’s aim was to establish a museum reflecting the history and lives of the people who lived and worked in the ancient Cornish landscape. Exhibits from his collection were originally displayed on the wayside in the Cornish village of Zennor for the benefit of passers-by. Today the Wayside Museum and Trewey Mill exhibits over five thousand artefacts alongside a fully working watermill producing organic flour.

British museums cover a vast array of collections and specialisms, from pencils to types of plastic. Pictured here is Brian Radam, curator of the British Lawnmower Museum, with an Atco Standard.

The approach proved popular and folk and open-air museums proliferated in Britain through the 1960s and 1970s with sites such as the Ulster Folk and Transport Museum (1958–67), Avoncroft Museum of Buildings, Bromsgrove (1963), Ryedale Folk Museum (1964), the Weald and Downland Museum at Singleton, West Sussex (established 1967, opened 1971), the Museum of East Anglian Life (1967), the Chiltern Open Air Museum (1976) and the Black Country Living Museum (1978) among others. While trying to capture local history through reconstructed environments, these sites tend to specialise in regional craft, environment and trade, from local geology and historic building techniques at Weald and Downland to the ‘into the thick’ underground mine experience at the Black Country Living Museum.

These places have not merely been concerned with rescuing good examples of vernacular architecture and the idiosyncrasies of bygone agricultural life however; through this period there was a drive to develop industrial open-air museums in line with wider concern about the preservation of Britain’s manufacturing past. By the late 1980s there were nearly five hundred museums featuring industrial content, approximately a third of which had been established since 1970. Two well-known sites best illustrate the trend: County Durham’s Beamish museum and Blist’s Hill Victorian Town in Ironbridge, Shropshire. The first of these, Beamish, opened to the public in 1972 with five staff on a 300-acre estate in the heart of the Durham coalfield. The result of a long campaign by Bowes Museum director Frank Atkinson, this was the first regional open-air museum, offering a depiction of a northern, industrial way of life that was rapidly disappearing with the demise of coalmining, shipbuilding and other heavy industry. The site features a collection of buildings re-sited from across the north-east, including Georgian houses from Gateshead, a pub from Bishop Auckland, a row of pit cottages from Hetton-le-Hole and a co-operative store from Anfield Plain, while the original site already included a farm and farmhouse, Pockerley Manor, a medieval defensive stronghouse, an eleventh-century manor house, Beamish Hall, and its own drift mine, closed only in 1962. Taken together the main collection (excluding Beamish Hall) represents a period from the 1790s to the 1930s, although interpretation focuses largely on two distinct periods – 1825, the year the Stockton and Darlington railway opened, and 1913, the peak coal production year in the north-east.

Inuit people and dwellings at Skansen, Sweden, the world’s first open-air museum.

The Henry Ford (also known as the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village) was the first open-air museum site in the United States, at Dearborn, Michigan.

From the mid-twentieth century Britain saw the establishment of a number of open-air museums based on collections of historic buildings, such as this Workmen’s Institute at St Fagans National History Museum, Wales. The Institute was built in 1917 as a centre for social, educational and cultural activities in the mining community of Oakdale, Monmouthshire. It closed in 1987, and was later dismantled and re-erected at the museum for the benefit of visitors and educational groups.

Meanwhile in Shropshire, the future of a unique historic environment in the Severn Gorge had been the subject of deliberations by the Dawley (later Telford) New Town Corporation. Now branded ‘the birthplace of industry’, the site was a case of ‘conservation through neglect’ where lack of investment and redevelopment had led to the survival of numerous locations associated with the early iron, brick, tile and pottery industries. It was here that Quaker manufacturer Abraham Darby first smelted iron-ore from coke commercially; decades later, in 1779, the world’s first iron bridge was built across the gorge by Abraham Darby III, and in 1802 Richard Trevithick’s locally built steam locomotive was driven over it. By the end of the eighteenth century a quarter of Britain’s iron was smelted at Ironbridge. New Town planning discussion led to the foundation of the Britain’s largest independent museum charity, the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust in 1967, and subsequent creation of an open-air museum, Blist’s Hill Victorian Town around Blist’s Hill furnace and part of the old canal network and ‘inclined plane’ at Coalport (the tracks used to transport materials between the railway and the canal). Since 1973 the public have been able to explore re-erected historic buildings, ranging from a school to a squatter’s cottage; watch demonstrations, including at the world’s only wrought-iron works; and buy heritage-style items from costumed interpreters in the village shops using special Blist’s Hill currency exchanged in a nearby bank.

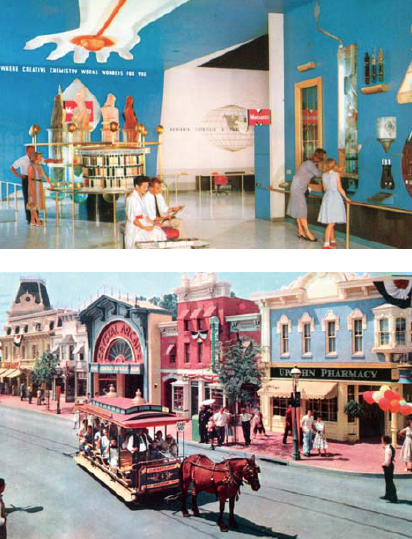

This points to an important distinction between open-air and indoor museum sites: the use of ‘living history’ practices. The term ‘living history’ has become the catch-all name for a range of dramatic interpretative techniques, ranging from craft demonstrations and re-enactments by enthusiasts to costumed interpreters who talk to visitors as a character, speaking in the first or third person, even sometimes feigning ignorance of modern life as part of the pretence. While the earliest open-air museums tended to opt for textbook-style ‘third-person’ interpretation, the influence of theatre as well as an increasing emphasis on visitor enjoyment, emotional experience and novelty, led to the growth of ‘living history’ styles of presentation and some heated debate as a consequence. Most notably, critics have cast aspersions on the exploitation of dying industry for entertainment, tourism and profit and the Disneyfied image of history that open-air museums allegedly present.

Epcot theme park, celebrating human achievement with interactive displays at Walt Disney World, Florida since 1982 (top), and historical re-creation Main Street, Disneyland (bottom). The Disney empire’s impact on attractions is such that ‘Disneyfication’ has been widely employed to criticise the authenticity and educational worth of some styles of museum interpretation and display.

While there is no doubt that open-air sites provide a selective and pleasant depiction of another time; re-creating the stenches and squalor, terror and pain of the past would undoubtedly transgress modern employment law and health and safety regulations, not to mention visitor expectations and demands. Authenticity and scholarship are often highly valued at open-air sites, which can mimic traditional museums in having large research archives and carefully checking provenance of objects on display. However such sites have in common an attempt to present a reconstruction as ‘real’ and provide a more immediate experience of the past for visitors. While ‘bringing history to life’ is a constant refrain, presentation is undoubtedly selective with emphasis placed on harmony and consensus at sites generally set in idyllic rural locations and rolling countryside. One issue here is the nostalgia effect: types of buildings or objects still in use have a direct appeal to the personal memory of visitors, which deepens their interest, empathy and emotional attachment to the past. Albeit seductive, this type of presentation can discourage critical engagement with and understanding of historical processes, while selling the idea that we can travel back in time. This is compounded by the fact that open-air museums are microcosms, artificial environments made up of buildings and artefacts from a number of different places and different times. As well as remembering, open-air museums can therefore cause visitors to forget: with divisions and misery side-stepped and heavy industry cleaned up, the format can serve to disguise the nuances and harsh realities of the very history that they claim to represent.

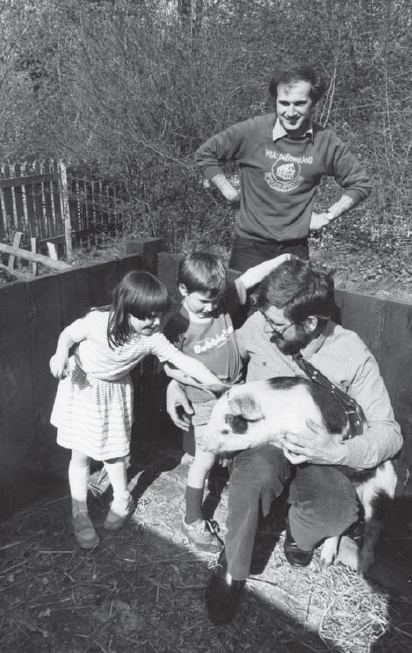

‘Hands-on’ learning at a living-history site. Children visit the first pigs at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum – Berkshire x Gloucestershire Old Spots bred locally in Sussex – observed by future museum director, Richard Pailthorpe.

The popularity of open-air museums, with their broad emphasis on the living history of regions and communities, is mirrored by the enduring appeal of historic house museums, which focus more closely on the lives of the individuals and families who previously lived there. Predominately, though not always, based at the past residences of famous (and infamous) people, these buildings provide a way to tell the story of their subjects’ lives and give a public glimpse into their private existence and daily routine. Their perpetual appeal is undoubtedly founded in a fascination with the minutiae of other people’s lives and a desire to understand what makes people tick. More than anything they illustrate the charm of biography, and in keeping with this, the list of historic house subjects is long: writers and artists, poets and politicians, men of science and of discovery, even fictional characters such as Sherlock Holmes, have all had sites opened in their name. From birthplaces to deathbeds, historic house museums have been founded around numerous locations from townhouses and humble cottages to sprawling country retreats. Some, such as Victorian Arts and Crafts pioneer William Morris have more than one residence to their name (Red House and Kelmscott Manor), others such as former Beatle Sir Paul McCartney (Forthlin Road, Liverpool) have had childhood homes opened to the public while still alive. In keeping with this, the significance of place may vary greatly: the Charles Dickens Museum in Doughty Street, London only played home to the author for a short period, 1837–9, while others such as Charles Darwin’s Kent home Downe House, and the Brontë Parsonage bordering the moors at Haworth were home for several decades and the scene of the bulk of the work for which their occupants are renowned. Scenes of profound events or ‘eureka’ moments of inspiration, creativity or invention, such as Newton’s apple tree at Woolsthorpe Manor undoubtedly have a certain panache. The same may be said of homes which afford an insight into aspects of an individual’s talent or professional life, such as designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s townhouse, 78 Derngate, Northampton, or Victorian artist Frederick Leighton’s richly decorated west London studio and home.

Considering the motivation to open such properties, the drive to present ‘hero history’ is strong. This can even extend to the opening of historic house museums belonging to less well-known albeit interesting relatives and friends. As one might expect, interpretation frequently tends towards the traditional, relying on room sets and stewards, audio tours, panels, leaflets and guides. Authenticity and atmosphere are understandably important, and the presence of original features and artefacts from the life of the subject holds greater interest and appeal than reproductions or period items shipped in. The temptation, evident at many historic house museums, is to create latter-day shrines to the property’s illustrious former inhabitant, or to freeze a building at just one point in its long history.

In contrast, growing interest in ‘history from below’ has led to a trend in recent decades for opening up and interpreting the homes of the ordinary, improvident and less well to do. Examples of this may be found in grocer Mr Straw’s House in Worksop, Nottinghamshire, or Birmingham’s last surviving court of back-to-back houses, both managed by conservation charity, the National Trust. The latter site presents each house as it would have appeared at a particular time between the 1840s and the 1970s, to educate visitors about change over time through comparison of the living conditions of ordinary people. Meanwhile, at country houses, in a reversal of the ‘upstairs-downstairs’ model, properties are sometimes presented from a servant’s perspective or seek to provide an insight into servant life. At the Errdig estate in Wales, for example, visitors enter the property through the kitchens, while sites such as Oxfordshire’s Chastleton illustrate the recent trend for ‘time capsule’ interpretation, striving to conserve a property as it was left, however unkempt.

On the approach to its 250th anniversary the British Museum undertook a major redevelopment programme, made possible by the removal of the British Library to a new building at St Pancras. The British Museum project centred around Lord Norman Foster’s Queen Elizabeth II Great Court, designed to serve as a striking civic space for the new millennium.