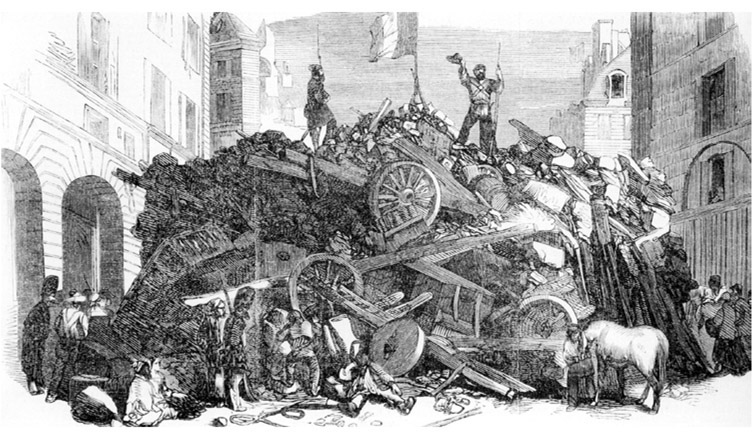

Barricade at the Rue Saint-Martin in Paris, French Revolution of February 1848. © SZ Photo / Bridgeman Images

From Barricades to Bonaparte

(1848–1851)

The barricades went up the night of February 23–24, 1848. Victor Hugo, on one of his regular tramps through Paris’s streets, asserted that there were some 1,574 of them, made up of 4,013 trees and more than fifteen million paving stones. His friend Alexandre Dumas, who was similarly drawn to turmoil, had already concluded that “the Prince protects us, it is true, but our real protector is the people. Within three days there will still be a great people, and there won’t be any small princes.”1

He was right. The king, Louis-Philippe, fled Paris for London on the morning of February 24 disguised as “Mister Smith,” leaving his palace and kingdom to the mob. Eighteen years before, in July 1830, a similar mob had exuberantly ushered out the last of the unpopular Bourbon monarchs and ushered in this same Louis-Philippe, the Bourbons’ Orléanist cousin, whose personal history and even appearance promised a change toward comforting moderation and prosperity. This stout bourgeois king, or Citizen-King as he was known, maintained happy relations with his subjects until the 1840s, when the economy began to sour.

Bad harvests, food shortages, rising prices, and growing unemployment now heightened the absence of liberty that the king’s subjects had hitherto been willing to tolerate. But no longer. It was in fact the specific curtailment of freedom of association (and its close relation, freedom of speech) that provided the spark that set off February’s 1848 revolution. Cleverly working around the regime’s restrictions on meetings, which were banned, reformers had settled on holding large-scale banquets, during which toasts served as a vehicle for political speeches. The regime failed to appreciate this distinction and banned one especially large banquet scheduled during January 1848. The organizers moved the date to February 22, charged an admission fee, and encountered similar opposition from the authorities. But now the small shopkeepers and craftsmen who had subscribed to the banquet were irate. They had paid their money and—having seen their voting rights recently curtailed, even while they suffered from a worsening economy—were determined to gain admission to the now-forbidden banquet.

The crowds grew, as workers demanding both work and bread joined in. Even the National Guard, largely made up of petty bourgeoisie with grudges to spare, went over to the reformers. A bad situation rapidly spiraled out of control when soldiers began shooting into the crowd. The dead were loaded onto carts and pushed through the streets of Paris to spectacular effect. By February 24, Paris was in open revolt, and the king fled.

What was left was a provisional government, whose attempts to mollify the workers quickly led to a number of concessions, including the right to work, the right to organize in unions, a ten-hour day (much shorter than the usual), and abolition of debtors’ prisons—in addition to establishing universal adult male suffrage and, of course, proclaiming a Republic, the second one since France’s great Revolution of the 1790s.

It was at this point that Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte arrived on the scene.

Louis-Napoleon, born in 1808—the son of Hortense de Beauharnais (daughter of Napoleon Bonaparte’s wife Josephine, by Josephine’s first marriage) and Louis Bonaparte, younger brother of Napoleon Bonaparte—was the product of a scheme to provide Napoleon and the now-infertile Josephine with an heir. This scheme was successful, in that Hortense and Louis produced two sons, but the couple had a dismal marriage. Louis-Napoleon’s detractors have contended that in fact his father was Hortense’s lover, the dashing Charles-Joseph, Count of Flahaut, who in turn was the illegitimate son of Prince Talleyrand. Those defending Louis-Napoleon have carefully tabulated calendar dates and locations of the parties concerned and concluded in favor of his legitimacy, which now seems to be widely accepted among those still interested in the question. Unaware, however, of parentage problems until later in life, little Louis-Napoleon enjoyed a childhood ensconced in imperial splendor at the Tuileries, Saint-Cloud, and Fontainebleau, thoroughly cosseted and spoiled by his mother and his maternal grandmother, Josephine.

Like both Hortense and Josephine, young Louis-Napoleon was a charmer, and he maintained his ability to captivate throughout his life. Certainly he was not a warrior leader in the image of his uncle: Louis-Napoleon’s military exploits were embarrassingly slight and came to unfortunate ends, although everyone who knew him insisted that he looked good on a horse. Instead, exiled (along with the rest of the Bonapartes) from France after Waterloo, he focused on seducing women, spending money, and enjoying himself. At the same time, this playboy-prince took considerable pride in his name and never ceased to dream that someday he would rule France.

This dream, as well as a longing for a dashing military role, led Louis-Napoleon into two abortive coup attempts, the second of which landed him in a French military prison where he studied, wrote, and consorted with a mistress, with whom he had two children before he eventually escaped for London. But his prison stay had not been without benefit, for during those long years he had widely published his political ideas—including a growing concern for the poor—in numerous articles and pamphlets. His L’Extinction du paupérisme, a study of the causes of poverty in France, was especially popular, going into multiple editions and drawing numerous reformers and workers to his cause.

His cause became ever clearer with the deaths, first, of his older brother; then of Napoleon Bonaparte’s only son, the young Duke of Reichstadt; and, last, of Louis-Napoleon’s father. These deaths left Louis-Napoleon as the foremost Bonaparte claimant to France’s imperial throne. By the 1840s, this had become markedly more significant, for Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had surged back into popularity in France, signaled by the 1840 return of his ashes to Paris, where he was interred with great ceremony in the Invalides. The Bonaparte name was now one that Louis-Napoleon could flaunt with pride in his native land.

This opportunity presented itself in February 1848, as revolution toppled yet another French monarch. Returning to Paris two days after Louis-Philippe fled France, Louis-Napoleon met with members of the Provisional Government and assured them that he was devoted to their cause. These leaders were, however, understandably wary and urged him to return to England as soon as possible, reminding him that the law of exile was still in effect. Louis-Napoleon gracefully acceded to their wishes and returned to London. There, he wrote his ardent supporter, the self-styled Count de Persigny, that “at present the people believe in all the fine words they hear. . . . There must be an end of these illusions before a man who can bring order . . . can make himself heard.”

Even more to the point, he told a friend, “I have wagered the Princess Mathilde [Bonaparte] that I shall sign myself Emperor of the French in four years.”2

Louis-Napoleon was right. Very quickly, conflict began to appear between the revolutionary workers and the far more conservative bourgeoisie. National Workshops, the provisional government’s solution to the unemployment problem, were proving unsatisfactory to everyone: government-sponsored public works did not supply enough jobs, leaving too many workers unemployed, hungry, and angry, while the bourgeoisie complained of handouts to lazy workers.

Street demonstrations from both sides provided an uneasy background to the April elections for a Constituent Assembly. Louis-Napoleon did not run. “So long as the social condition of France remains unsettled,” he wrote a friend, “I feel my position in France must be very difficult, tiresome and even dangerous.”3 The electoral turnout was huge (making use of printed voting slips for the first time in French history) and resulted in a victory for a liberal Republic—a middle way between social revolution and monarchical reaction. The deputies now reproclaimed the Republic, making May 4, 1848, the official birth of the Second Republic.

But the workers still had grievances and revolted, first in Rouen, then in Paris, where they invaded the Assembly chamber itself. As the earlier spirit of reconciliation faded, attitudes became increasingly polarized. By-elections in early June brought a troubled Victor Hugo into the Constituent Assembly, backed by a committee of moderates.4 Hugo’s politics thus far had favored the monarchy—although after being elevated to the peerage in 1845 and entering the Senate, he had spoken out against the death penalty and social injustice. During the February 1848 riots, he had supported a regency for Louis-Philippe’s grandson. But now what? He did not like what he saw emerging from the political right.

The June by-elections also brought Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte into the Assembly, although with becoming modesty. Claiming that his friends had announced his candidacy without his approval, he won in all four departments (including Paris) in which his name was placed, without so much as waging a campaign. Although some strongly urged that he be disqualified (on the grounds that the law banning him from France was still in effect), the majority admitted him to the Assembly. But then, on his own initiative, Louis-Napoleon sent a letter of resignation, prompting many later to wonder whether this was genuine hesitation or whether he was simply waiting for a better moment.

The ax was now about to fall on the National Workshops. A June decree gave workers a choice between enlisting in the army or departure for hard labor in the provinces. Workers rose up in a massive revolt (later called the “June Days”), with barricades going up, bullets whistling, and intense fighting between the army—under a relentless General Cavaignac, joined by a heavily bourgeois National Guard—and the increasingly desperate workers.

The young poet Charles Baudelaire took part in the street fighting, siding with the workers and using his own rifle to fire at government troops. Shooting from the government’s side was Gustave Flaubert, also in his twenties. According to his friend, the writer Maxime Du Camp, Flaubert “shouldered a fowling piece [and] joined the ranks of my company [in the National Guard].” Baudelaire and Flaubert escaped injury, but Du Camp was wounded and had a long convalescence.5

Victor Hugo, who at the time lived in the once-elegant but increasingly decrepit Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges) in the heart of the insurrection, unsuccessfully attempted to return to his family before learning that they had escaped unharmed. Sent with other representatives to inform the insurgents that their cause was a lost one and that General Cavaignac was in control, he ended up leading a contingent of the Republican Guard against a series of barricades, directing cannon fire, taking prisoners, and contributing to the deaths of countless insurgents, whom he considered heroic but tragically misguided.

Hugo told himself that he was engaged in nothing less than “saving civilization.” Yet what he saw on those June days and nights seared itself into the unforgettable memory that he recorded in Les Misérables—a vision of one of the largest barricades of this 1848 insurrection, “the biggest street-war in history.” This barricade was not to be confused with his own story’s far smaller barricade of 1832, but was instead the gargantuan one that stretched across the main road leading into the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, the sight of which “conveyed a sense of intolerable distress which had reached the point where suffering becomes disaster.” Distress ennobled it, for this monstrosity was both “a pile of garbage, and it was Sinai.”

Conflicted about the role he had played in this tragedy, Hugo added, “These are popular upheavals which must be suppressed. The man of probity stands firm, and from very love of the people opposes them.” Well, in any case, he had done so, and a bitter memory lingered. With a sigh, he concluded, “Duty is burdened with a heavy heart.”6

“For two days,” Maxime Du Camp later wrote, “the contest was a doubtful one, but finally the cause of civilization carried off the victory, and General Cavaignac was proclaimed the savior of the country.”7

Order was quickly reestablished, and the reprisals began. Executions proceeded smartly, and about fifteen thousand men were arrested, piled into improvised prisons, and deported to Algeria, France’s recent colonial conquest. At the Assembly’s insistence, the National Workshops were completely dissolved, and General Cavaignac—a republican, albeit a stern one—became leader of the Republic, at least until a president could be elected.

The young scholar Ernest Renan, then studying in Paris, wrote to his sister after touring the worst affected areas: “In Rue Saint-Martin, Rue Saint-Antoine, and the part of Rue Saint-Jacques stretching from the Pantheon to the docks, there was not one house that had not been lacerated by cannon fire. Some you could literally see through.” Maxime Du Camp noted proposals “to take up all the paving-stones of Paris, macadamize the streets so as to close the era of revolution forever.”8 He was specifically referring to certain quarters of the city, for by now, the contrast was clear between eastern Paris, where the insurgency had erupted, and the more bourgeois neighborhoods in the city’s west.

Order was returning, and with it, suppression. Leftists Adolphe Blanqui and François-Vincent Raspail were already in jail, and others, including Louis Blanc, now escaped to London. A new law abolished the recent reform that had established a ten-hour working day in Paris, now lengthening it to twelve hours, and a series of regulations served to muzzle the press—“silencing the poor,” as one irate lawmaker called it.9 In addition, Paris—where the position of mayor had been briefly restored after its disappearance during the long years of postrevolutionary monarchy—once again lost its mayor and its autonomy, and the prefect of the Seine again became the capital’s chief executive.

Louis-Napoleon considered all of this with interest and, after careful consideration, decided to stand in the September 1848 by-elections. He swept the five departments where he was a candidate (one more than those he had won in June), and he chose to represent the department of the Seine. When he arrived in Paris on September 24 at the Paris embarkation point of the Great Northern railway (now the Gare du Nord), he carried with him a color-coded map of Paris—his plan for renewing the great city—along with dreams for improving the lot of workers and the entire nation.

The Assembly welcomed him and suspended the banishment order. Even Victor Hugo was enthusiastic: “The man just named by the people as their representative,” he proclaimed, was in his eyes a worthy heir of the great Bonaparte; “his candidacy dates from the time of Austerlitz.”10 Louis-Napoleon informally subscribed to a number of the progressive ideas that then were circulating, which held in common an optimistic view of the emerging industrial revolution and its promise for one and all. Jobs and riches could be had for worker and bourgeoisie alike if only the old way of doing things could be cleared away and replaced with the new. Regarding Paris in particular, Louis-Napoleon was thoroughly convinced that misery and mobs would disappear if only the narrow, festering streets could be demolished and broad thoroughfares created in their place, letting sunshine in and allowing the free flow of commerce as well as the activities of daily life.

The Provisional Government had already chalked up several potential public works in Paris, largely to satisfy the job requirements of the short-lived National Workshops. These included the completion of the northern wing of the Louvre Palace (the wing begun under Napoleon Bonaparte) and the continuation of the Rue de Rivoli (another Napoleon project). This had stalled in its eastward course alongside the Louvre’s uncompleted northern wing, reaching only a point even with Napoleon’s nearby Arc du Carrousel. Nothing for the moment came of these plans, but the government did in fact make a significant change in the law on compulsory purchases (eminent domain) that would have huge impact in Paris’s future: this now allowed the city to purchase the entire portion rather than just the precise area of land directly affected by whatever public works were involved.

Louis-Napoleon believed in the socialistic philosophies of his age, and he dreamed of initiating major public works that would foster progress and benefit one and all. But unlike those who had ardently supported the National Workshops or something like them, he believed in the necessity for good, solid organization. Indeed, his distaste for the National Workshops did not so much derive from a horror of handouts to what the bourgeoisie regarded as the undeserving poor as it recoiled from the sheer disorganization that riddled the project.

He firmly believed that he could do better, and in late October, when the Constituent Assembly set December 10 as the date for the presidential elections, Louis-Napoleon immediately announced that he would run.

At last, on November 4, 1848, the Second Republic had a constitution. This document, which the Constituent Assembly overwhelmingly approved, provided for a single Legislative Assembly and a president with full executive powers, both to be directly elected by universal male suffrage. This president would serve a four-year term and, most importantly—especially for those who cast a worried glance in the direction of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte—would not be eligible for reelection.

It quickly emerged that Louis-Napoleon’s main opponent would be none other than General Cavaignac, who was widely favored to win. Cavaignac, of course, was by then known as the man who had “gunned down the workers,” and Louis-Napoleon—who had made no public pronouncement whatever following the riots—is supposed to have remarked (at a London dinner party in the riots’ aftermath): “That man [Cavaignac] is clearing the way for me.”11

But Louis-Napoleon would benefit not only from worker support but also from the forces on the right—those conservatives (such as King Louis-Philippe’s former prime minister, Adolphe Thiers) who had always been un-enthusiastic about the Republic. Bonaparte easily promised them whatever they wanted and, according to historian Maurice Agulhon, “seemed to be a mediocre, simple-enough fellow whom it would be easy to maneuver in the corridors of power.”12

Certainly the general atmosphere in Paris had changed and not in Cavaignac’s favor. Maxime Du Camp noted this upon his return to Paris after an absence of several months. As he put it, “I was astonished at the change which had taken place in my absence. General Cavaignac, when I left Paris, was a great man—a savior of society. . . . Our French weather-cock had had time to turn, and it was ‘Cavaignac is a revolutionary just like the others.’” Reaction, he added, “‘was setting in’ with a will.”13

Louis-Napoleon’s right-hand man, Persigny, campaigned as he had in September, using the ample funds provided by Louis-Napoleon’s faithful (and wealthy) mistress, Lizzie Howard, to flood the streets of Paris and all the major French cities with posters, leaflets, and placards, in addition to match-boxes with the candidate’s portrait, medals on red ribbons with his effigy, and miniature French flags bearing his name. Persigny also bribed journalists to insert articles favorable to Louis in newspapers otherwise hostile to the candidate and paid street singers to sing songs acclaiming him. It was new, it was modern, and the public loved it. The public also took to Louis-Napoleon personally, despite (and perhaps even because of) his lack of polish as a speaker. Whereas Cavaignac was aloof and military in demeanor, Louis-Napoleon exuded charm and connected instantly with ordinary people. Riding through Paris on horseback, he took pleasure in greeting crowds in the streets and talking with soldiers in the barracks.

Still, it came as a surprise to most seasoned politicians when this Bonaparte upstart, as many derisively called him, demolished Cavaignac on election day, December 10. Louis-Napoleon had promised peace as well as prosperity, and having thus reassured those who dreaded another Bonaparte on the loose in Europe, he found his base among a large majority who favored a return to order under an approachable leader with a pleasant smile—especially one with a legendary name.

Ten days later, he took the oath of office, swearing “to remain faithful to the democratic Republic.” He then read a brief speech in which he extolled the Republic and again promised it his complete loyalty.

According to Victor Hugo, many representatives were reserved in their applause, not knowing whether they were witnessing “a conversion or a perjury.”14

Victor Hugo adored Paris and had done so ever since he could remember. The youngest son of an officer in Napoleon Bonaparte’s army, Hugo was born in 1802 in Besançon, near the Swiss border, but arrived in Paris soon after, when his mother, a confirmed royalist, left Major Hugo to his mistress and his wars. Settling in Paris with her three sons, Madame Hugo acquired a lover of her own, who actively plotted against Bonaparte until ending up facing a firing squad.

In the midst of this turbulent family life, young Victor went back and forth between mother and father (now a general), between royalist and Napoleonic sympathies, and between Paris, Italy, and Spain. Even Paris offered little stability during his early years, as one home depressingly followed another. But in the midst of this unsettled life, young Hugo began to write and found that he was good at it, winning a major prize when he was fifteen and (with his older brothers) founding a literary review that he filled with torrents of poetry and prose.

Yet even these successes could not distract from the Hugo family’s mounting troubles, including the unmistakable evidence that Victor’s brother Eugène was going mad. On the day of Victor’s wedding to Adèle Foucher, Eugène permanently slipped into insanity and spent the rest of his brief life in confinement.

Life for young Victor Hugo was already looking a lot like one of his emotion-packed novels. Still, there were more serene moments, and by his midtwenties, he was beginning to achieve a literary reputation and the income to go with it. He now began to write plays and made his triumphal debut at the Comédie-Française with Hernani, where it prompted riots with its daring new Romantic style.

But it was the 1831 publication of Hugo’s remarkable novel Notre-Dame de Paris that really announced his arrival as a literary star. Huge, sprawling, and fairly dripping with emotion, this dark Romantic tale quickly became a best seller and was translated into countless foreign languages, including English, where (much to Hugo’s dismay) it was retitled The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Passionately drawn to the medieval architecture and poverty-mired inhabitants of this ancient cathedral quarter, Hugo turned his novel into a demand for social justice as well as an elegy to the past. In the process, he saved Notre-Dame, for his book prompted a surge of public attention to the dying cathedral, resulting in the enormous restoration efforts that followed.

Given his considerable earnings from Notre-Dame de Paris, Hugo now could afford to move his family to 6 Place Royale (now the Place des Vosges), the most well-known of his many Paris residences. Here in this beautiful seventeenth-century square—which Hugo shrugged off as too modern and architecturally uninteresting—he lived for sixteen years in the height of Gothic comfort. It was now that he established his liaison with actress Juliette Drouet that would last the rest of his life, while his wife, Adèle, turned to Hugo’s friend, the writer and critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve.

This could not have been the happiest of households, and indeed, after an 1847 visit, Charles Dickens gave a memorable description. From Hugo’s wife (“who looks as if she might poison [Hugo’s] breakfast any morning when the humor seized her”) to his daughter (whom Dickens suspected “of carrying a sharp poignard in her stays”), Dickens was struck by the family’s over-the-top creepiness, ensconced “among old armor, and old tapestry, and old coffers, and grim old chairs and tables.”15

Still, Hugo seemed content in this remarkable setting and continued to pour out torrents of words, including the initial portion of Les Misérables. Revolution and imperial coup would drive him from his home and his country long before the final version of the book would appear.

Seventeen-year-old Edouard Manet, writing to a friend in February 1849, asked: “How do you feel about the election of L[ouis] Napoleon[?]” He then added, “For goodness sake don’t go and make him emperor.” Soon after, Manet wrote to his father: “So you’ve had more excitement in Paris; try and keep a decent republic against our return, for I fear L[ouis] Napoleon is not a good republican.”16

At this time, young Manet was aboard a naval training ship bound for Rio de Janeiro, having acquiesced to family insistence that he find a career, any career, after the young man’s poor school record negated any possibility of following his father (a distinguished lawyer in the Ministry of Justice) in the law. Young Edouard reluctantly agreed to give up his dream of becoming an artist and took the naval exams but failed them. Then, after a change in navy regulations made it possible to reapply after making a voyage south of the Equator in the merchant marine, Edouard’s determined father signed him up on a vessel bound for Rio. Edouard made the best of it and seemed to enjoy the voyage, crossing the equator on January 22, 1849, with the usual crossing-the-line rituals, and finding suitably exotic entertainment in tropical Rio. After his return to Paris in June, though, Edouard again dashed his father’s hopes by once again failing the naval entrance exams. At long last, Manet père gave in to his son and agreed to let him go to art school.

This meant either studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, with its Academy of Painting and Sculpture, or entering a private atelier. The former offered a highly formalized and classical training, largely with members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, and emphasized drawing the human figure and copying Old Masters in the Louvre. The aim here was to win special competitions—the most exalted being the Prix de Rome. Instruction in private ateliers, on the other hand, could be less rigid, and among these, the ateliers of Charles Gleyre and Thomas Couture were the most prominent.

In time, Charles Gleyre would attract young Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. But now, Edouard Manet opted for Thomas Couture, and in January 1850 he entered Couture’s atelier—located just inside what then was the Farmers-General wall, at the foot of Montmartre.

Louis-Napoleon began his presidency of the Second Republic with a certain amount of discretion. Despite his long history of proclaiming himself heir to the Empire, he went through the motions of swearing loyalty to a constitution that forbade him from seizing what he had always regarded as rightfully his.

Some of his first steps were to reinforce his image as benefactor of the people. Envisioning huge green spaces for the city as well as a major road-building program, he soon ordered work to begin on the Bois de Boulogne. Paris at that time had four public parks: the Luxembourg Gardens, the Jardin des Plantes, the Tuileries gardens, and the gardens of the Palais Royal, all in the city’s center. But Louis-Napoleon saw a need for parks on the city’s growing outskirts. The lands of the Bois de Boulogne, immediately to the west of Paris, belonged to the state, but the new president soon provided for their transfer to the city free of charge, on condition that they be turned into an area for public walking and relaxation. Louis-Napoleon’s idea, based on his years in London, was to create a curving watercourse there modeled on Hyde Park’s Serpentine. It was, in theory, a pleasing idea, and Louis-Napoleon eagerly awaited the outcome, as teams of workmen set to digging.

But before long, the new president began to take other steps, these ones carefully calibrated to consolidate his power. Soon after assuming the presidency, Louis-Napoleon formed a government of former royalist notables and cronies, completely excluding any republicans. And, working to curb resistance in the Legislative Assembly, whose large republican majority still distrusted him, he and the Assembly’s right wing forced through spring elections. These, which (like the presidential election) were based on universal male suffrage, installed a legislature more to Louis-Napoleon’s liking, delivering a crushing victory for the bourgeois party of order (the order of obedience rather than the order of law). No matter that the leaders of the right regarded Bonaparte as an adventurer and an illegitimate one at that; they and he shared a fear of a democratic upsurge. While these leaders of the right dismissed any possibility that he could rule without them, Bonaparte saw things entirely differently and was quite willing to accept their help until he no longer needed them.

In the meantime, this new majority for the French right had an immediate impact on affairs far from home, for Louis-Napoleon—whose sympathy with Italian unification and independence dated from his youth, when he and his brother fought with Italian revolutionaries against Austrian domination in northern Italy—now agreed with the strongly Catholic French right to support the temporal power of the pope. The papacy had dominated much of central Italy for centuries, but now the Papal States were under attack from nationalists inspired by the same waves of reform and revolution that had swept France and other countries in 1848. In early 1849, Italian nationalists under Giuseppe Mazzini declared a Roman Republic, and the pope fled Rome. Louis-Napoleon’s conservative Catholic backers now strongly urged him to go to the pope’s aid. Despite his sympathy for the revolutionaries, Louis-Napoleon was not about to risk his own political power. The French army attacked Rome, ousted the republicans, and welcomed back the pope.

Since this military action was directly in contradiction to the French constitution (which stated that the Republic “respects foreign nationalities just as it expects its own nationality to be respected . . . and never employs its forces against the liberty of any people”), the political left attempted to protest, with peaceful demonstrations. But these protests failed. The Parisian workers, still traumatized by the bloody days of June 1848, did not show up, and in those cities—such as Lyon—where they did, they were brutally repressed. “No one could say that the Government erred on the side of leniency,” Maxime Du Camp observed, adding that from 1849, “the prisons were crowded with political journalists.” For his part, a newly authoritarian Louis-Napoleon proclaimed that “it is time that the good took heart and the bad trembled.”17

The tide of revolution had definitely turned. French forces turned a subdued Rome back to the pope, who embarked on severe repression. Soon after, Austria retook an insurgent Venice and crushed the Hungarian revolution. Later, Maxime Du Camp wrote that “as early as . . . June, 1849, the more sagacious spirits foresaw what the end would be, but neither Flaubert nor myself suspected anything.”18

In October 1849, Louis-Napoleon announced that he was forming a ministry that would be accountable to him alone and that henceforth the Assembly would be narrowly limited in its legislative responsibilities—meaning that it would be dependent upon the direction of the president. Victor Hugo, who had believed that Bonaparte was preferable to Cavaignac, now saw the light and, in a speech to the Assembly, denounced the regime’s brutality. With this dramatic switch, he found himself in the company of a growing network of international socialists, including revolutionaries from the popular uprisings that had recently swept Europe. Hugo even chaired an international peace conference in Paris in August 1849.

But Hugo and those now fearing for the Republic could do little or nothing to stop the train of events, especially since conservatives in the Assembly were still willing to put up with almost anything from Bonaparte so long as they got what they wanted in return. In particular, this meant the establishment of control over public education by the Roman Catholic Church, a longed-for event that became law (the Falloux law) in March 1850. Church-run public education had always appealed to the party of order, whose clerical ties were strong, but it became essential now with the introduction of universal male suffrage. Who, indeed, would teach the workers and the peasants? Who would guide them in their opinions? With the Falloux law, the Church rather than the State became that mentor, in public as well as spiritual affairs—giving rise to hard-fought opposition that would last through the rest of the century.

A last-ditch effort on the part of the left came in the spring 1850 by-elections, as the left put up the writer Eugène Sue for one of the Paris districts. Sue, raised in wealth, had wandered extensively in Paris’s slums and, in the early 1840s, had conveyed his appalled reaction in a wildly popular series of novels, Les Mystères de Paris (The Mysteries of Paris). It was Sue who introduced readers to the horrors of the tapis-franc, a word that—“in the slang of theft and murder,” as Sue put it—signified “a drinking shop of the lowest class.”19 These foul dens were in turn run by degraded beings called “ogres” or “ogresses,” depending on their sex, and attracted the lowest of the low. Sue’s readers descended with him into the depths of these places where in real life they would never, ever dream to go and cried out for reform—as he meant them to.

It was as a reformer that Sue took his seat in the Assembly in 1850, after an overwhelming victory. But his victory—and that of Sue’s left-wing Paris colleagues—signaled a still-resilient element of resistance among Paris workers that alarmed the thoroughly bourgeois party of order. These now determined to do something about the dangers of universal suffrage and set to work to restrict the number of those eligible to vote. The outcome, a law of May 31, 1850, did the job nicely, establishing numerous requirements, including the necessity of having paid a personal tax; of having committed no offense, no matter how trivial; and of having stayed at one address throughout the prior three years—the latter being an impossibility for those in search of work. This law easily passed, and the result was exactly what the political right desired: it reduced the electoral body by almost one third. Although no one knew for sure that all of these votes would have gone to the left, it was generally accepted that the left now had no chance of winning the 1852 elections.

The atmosphere of revolution was rapidly disappearing in Paris, as streets were repaved and houses rebuilt. Even the trees of liberty, planted with much ceremony during the revolution’s early days, were now uprooted. Social life resumed, with elegant receptions for those in high society and crowded cafés along the boulevards for lesser mortals.

Louis-Napoleon, still a bachelor at forty, enjoyed his pleasures, and Lizzie Howard—the maȋtresse en titre, or official mistress, as some snidely called her—was only one of a bevy of women with whom he dallied. The Palais de l’Elysée, where he lived (making a point of not moving into the Tuileries, where his uncle Bonaparte had resided) now glittered with splendid balls and receptions. Louis-Napoleon was creating a court around him, and he was looking more and more like an emperor-in-waiting. He flooded army leaders with flattering attention, made regular appearances throughout the country (where he said the right things in the right places), and began to encourage revision of the constitution—in particular, that bothersome section limiting his presidency to one term.

Royalists as well as liberals became increasingly alarmed, especially when, in early 1851, Louis-Napoleon formally requested that the Assembly revise the constitution so he could be elected for another term—on the grounds that this was of the utmost importance, to allow him to continue his mission of doing good and improving the lot of the people. A constitutional revision needed a three-quarters majority to pass, and as Louis–Napoleon toured the provinces, trying to drum up support outside of Paris, Victor Hugo did his utmost to prevent passage, giving an especially thrilling July speech to the Assembly that introduced his famous slam: “Just because we had Napoléon le Grand,” he demanded, “do we have to have Napoléon le Petit?!”20

Hugo turned back the tide—Louis-Napoleon just missed getting the 75 percent vote he needed to change the constitution. Although the president could do nothing about Hugo, who as a legislator was legally immune, he could and did take other steps of petty revenge, going after Hugo’s son Charles, who edited the influential and by now strongly anti-Bonaparte newspaper, L’Evénement. Charles, although dramatically defended in court by his father, was convicted of contempt and sentenced to six months in the bleak Conciergerie. Soon after, Hugo’s other son, François-Victor, was sentenced to nine months for having urged the government (in L’Evénement) to extend political asylum to foreigners, and L’Evénement itself was shut down.

But Louis-Napoleon still did not have the constitutional amendment he wanted, and in lieu of this, he began to consider stronger measures. “The President wanted to suppress the Assemblée, the Assemblée to suppress the President,” wrote Maxime Du Camp. “No one knew when the crisis would occur, but all were sure that it was inevitable.”21 Rumors of conspiracy flooded Paris, even as Louis-Napoleon considered a September coup but was discouraged by advisers who reminded him that all the leftist representatives in the Assembly would be away from Paris at the time, having gone to their districts for their parliamentary recess. Wait, they advised him, until these representatives returned to Paris in November, so they could be more easily rounded up.

Louis-Napoleon, in his best friend-of-the-people mode, now proposed the repeal of the repressive May 1850 election law. The party of order was appalled, while the republicans were in a flurry, not knowing which way to turn. In the end, most on the left were persuaded that the principal danger remained with the party of order. As Victor Hugo observed in his notebook: “I am not particularly alarmed by the Elysée [Louis-Napoléon], but I am worried about the [conservative] majority.”22 The president’s proposal was roundly defeated, doing him no harm whatever but adding significantly to confusion and unrest among the legislators.

One night in late November, the Count de Morny invited Maxime Du Camp to show the president the photographs he had recently taken while in Egypt. Du Camp was an early and enthusiastic amateur photographer, and—as he put it—“at that time [my photographs] were an object of interest, for I was the first to reproduce in this manner the different architectural monuments of Cairo, the ruined temples on the banks of the Nile, the various points of view at Jerusalem.”23 At that time, the Count de Morny himself was also an object of considerable interest, being no less than Louis-Napoleon’s illegitimate half-brother.

De Morny, whose illegitimacy was both uncontested and unregretted, was the love child of Louis-Napoleon’s mother, Hortense, and the Count de Flahaut. He was three years younger than Louis-Napoleon, and the two had never met until 1849, although Louis-Napoleon learned of his half-brother’s existence soon after their mother’s death. Described as both “ruthless and charming,” de Morny had fought “with great distinction” in North Africa before exchanging his military career for an equally successful (and undeniably ruthless) one in business, making a huge fortune through a series of lucrative but arguably unscrupulous speculations. Although a loyal supporter of the former monarch, Louis-Philippe, Morny had never confused loyalty with his best interests, and after Louis-Philippe’s ouster, he quickly navigated to his half-brother’s side. Their first meeting was not warm, as the two brothers figuratively paced around one another, sizing each other up. But it ended with Louis-Napoleon observing, “You have a great future to play in the future of France. . . . I will have need of you.” Morny in turn declared his devotion, and the pact between them was sealed.24 Morny quickly became one of Louis-Napoleon’s closest advisers.

And so when the Count de Morny asked Maxime Du Camp to show his collection of photographs to the president, whom he thought they might interest, Du Camp promptly appeared on the agreed evening in late November at Morny’s Champs-Elysées residence. There, President Louis-Napoleon graciously received him and several others and questioned Du Camp knowledgably about the history surrounding some of the photographs. As the president was leaving, he told Du Camp: “I am at home always on Mondays; I shall hope to see you.”

Soon after, Du Camp dined in town with Morny and several others, and in the course of the evening, Morny asked him, “Shall you go to the Elysée on Monday?” Although flattered, Du Camp replied with some hesitation and a shrug. But Morny pressed him. “Do come,” he told him. “It will interest you.”

Accordingly, on Monday, December 1, 1851, Maxime Du Camp went to the Elysée Palace at about nine in the evening. Noting that there were not many present at the reception, he was interested to see one of Louis-Napoleon’s most loyal officers approach the president, who advanced toward him and held him by the button of his coat while speaking with him in low tones for nearly twenty minutes. When the officer left the room, someone joked that the fellow had gone out “as if he was the bearer of a State secret.”

As Du Camp soon realized, this was the absolute truth. Louis-Napoleon had confided his project to the man, “and that very night the blow was to be struck.”25