Léon Gambetta leaving Place Saint-Pierre, Montmartre, by hot-air balloon on 7 October 1870, during the siege of Paris. Painting by Jules Didier and Jacques Guiaud. © Musée de la Ville de Paris, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, France / G. Dagli Orti / De Agostini Picture Library / Bridgeman Images

An End and a Beginning

(1870–1871)

The morning after the Republic was declared, Victor Hugo appeared at the Brussels train station and requested a ticket to Paris. “I have been waiting for this moment for nineteen years,” he told the young journalist who was with him.1

He crossed the border into France at four o’clock in the afternoon, and that evening he arrived at the Gare du Nord, where he was greeted by a huge cheering crowd. Never one to shy from an audience, Hugo pushed his way into a café, where he spoke from a balcony. “Citizens,” he told them, “I have come to do my duty.” He had come, he added, “to defend Paris, to protect Paris”—a sacred trust. After that, he climbed into an open carriage, from where he spoke again to the fervent crowd before making his way to the house of a friend, near Place Pigalle.

There the young mayor of Montmartre, Georges Clemenceau, warmly welcomed him.

Filled with republican ideas and ideals, Clemenceau had returned a month earlier to Paris, where he immediately became immersed in politics, with special attention to the emergence of a Republic. Given his many friends in the new government, it perhaps was no surprise when Clemenceau was appointed mayor of Montmartre.

At that time, Montmartre consisted of its steep hill, or Butte, on the northern edge of Paris and was the second most populous arrondissement, or district, in the city. It also was the home for many of Paris’s poorest residents. Scarred by quarries on its southern slope and still open on top (this was before Sacré-Coeur), Montmartre in 1870 was steeply pitched and poverty-stricken, networked with unpaved narrow streets and a jumble of houses filled to brimming with many of those who had been expelled by Haussmann’s grands travaux from Paris’s center.

Clemenceau’s left-wing politics and devotion to his constituents would win him widespread support during the difficult months ahead—especially from Louise Michel, with whom he worked to help the most destitute of Montmartre’s residents. Together they organized distribution centers for food and medicine and started up free schools for the children.

He would soon open a dispensary where, for two days a week, he cared for Montmartre’s impoverished residents free of charge. But the appalling conditions he saw around him urged him to focus on his career in politics, where he thought he could bring about change. In time, his remarkable career as both a politician and journalist would culminate at the top, as prime minister of France, during the anguished years of yet another war with Germany.

Baron Haussmann’s career, on the other hand, was over. Recognizing the dangers of remaining in Paris, he had prudently left for Bordeaux as the empire collapsed, fleeing with other officials of the Second Empire. But when it appeared that even Bordeaux might not be safe, he crossed the border into Italy, using an assumed name and false passport. Haussmann would remain there, in exile, until it seemed safe to return.

Many others, including the Rothschilds, found their lives completely disrupted by the war and the collapse of empire. For the first time in their family history, the Rothschilds suffered a severe rupture: the Frankfurt branch wholeheartedly supported Prussia, while the Paris branch unequivocally defended the French, with two of its younger members serving in the Garde Mobile. This led to severe reprisals when the Prussians occupied the family château at Ferrières en route to Paris. Whether or not the Prussians actually looted and pillaged the place (this is in dispute), they certainly behaved badly, and Bismarck seems to have taken malicious pleasure in the fact that the château they occupied was Jewish-owned.

Another whose life was upended was Sarah Bernhardt, whose flourishing theater career came to an abrupt halt as theaters closed and actors left for military duty. When the German army began to close in on Paris, she decided against leaving, although she managed to get her mother, sisters, and son to Le Havre and safety. She then decided that since the actresses at the Comédie-Française had turned part of their theater into a hospital for the wounded, she could do the same at the Odéon.

Bernhardt pulled strings, got permission, and then hunted up supplies. Luckily, the handsome new prefect of police was charmed by her visit and was more than willing to round up the food and supplies she needed. Ten barrels of wine, thirty thousand eggs, and one hundred bags of coffee soon arrived at the Odéon, along with an unexpected five hundred pounds of chocolate, a gift from the Menier chocolate-makers. In response to her appeals, others presented her with a flood of supplies, including overcoats, slippers, and lint and linen for bandages.

The wounded began to flood in as well, forcing her to set up beds in the theater’s auditorium, dressing rooms, foyer, and even the bar. The wounded were never-ending, even as the weather became colder and food became scarce.

But the worst days were yet to come.

Edouard Manet was ecstatic about the end of the Second Empire, but he recognized the perils that lay ahead. Skeptical of the new government’s claims that the Prussians would grant an armistice to the new Republic, he and many others prepared for a siege. Remaining in Paris as a volunteer gunner in the National Guard, Manet nonetheless was not about to subject his family to the dangers and deprivation of staying. Instead, he promptly sent his wife, his mother, and his wife’s son to safety in the south of France.

Manet also sent his most precious pictures into hiding with his friend Théodore Duret, who had offered to keep them safe. These included Olympia, The Luncheon on the Grass, The Guitar Player, The Balcony, and others. Scrawled along the side of his note to Duret were the words: “In the event of my death, you can take your choice of Moonlight or Reader, or if you prefer, you can ask for the Boy with the soap bubbles.”2

Writing to Eva Gonzalès on September 10, Manet told her that many were hastily exiting the city. “It’s a debacle,” he wrote, “and people are storming the railway stations.” Writing to his wife on September 11, he reported, “We’re expecting the Prussians any day now.” He continued to write her almost daily, even when on guard duty at the fortifications (the massive Thiers fortifications surrounding Paris). On September 20, he wrote, “There’s fighting everywhere, all round Paris.” By September 21, Prussian troops had surrounded Paris; soon after, he told her that “Paris is determined to defend itself to the last.” On guard at the ramparts, “we heard the guns going all night long. We’re getting quite used to the noise.”3

Manet worried when he did not hear regularly from Suzanne and was “tormented by the thought that you’re without news of us”—a situation which became all the more common once the Prussians closed their siege around Paris. From then on, all communications in and out of the city had to be carried out by balloon and homing pigeon, a formidable task.

At the war’s onset, Nadar and two others had formed the No. 1 Compagnie des aérostiers (No. 1 Balloonists’ Company) and proposed that they make tethered ascents from Montmartre to provide reconnaissance for the military. After the empire’s fall and the continuation of the war, Nadar volunteered to assist his city during the siege. Without waiting for official sanction, he and his colleagues established a base on top of Montmartre and began their first tethered ascents before the Prussians completely encircled the city. Clemenceau, as mayor of Montmartre, at first objected, but then changed his mind and provided the balloonists with tents and straw to keep them warm at night.

The provisional government, which had escaped to Tours before the Prussian encirclement was complete, never read or acknowledged the observations Nadar and his colleagues made—marking French, Prussian, and unidentified troops on maps of the Paris region. But now, with Paris encircled, Nadar proposed that the balloons for the first time be untethered and float sacks of correspondence over the Prussian army toward Tours—in what amounted to the world’s first air mail.

His idea was accepted, and on September 23, Le Neptune took off from Montmartre with more than two hundred and fifty pounds of mail and dispatches. Not only was the flight risky—the balloons were fragile, and the Prussians could easily use them for target practice—but the question remained, how to get news back? It was impossible to steer a balloon accurately enough to make a pinpoint landing in a besieged city.

The answer was homing pigeons. Le Neptune and the balloons that followed carried caged birds that flew back to the capital. But how to manage the weight of mail they must carry? Here, an especially ingenious solution presented itself. An unidentified engineer approached Nadar with the proposal to gather the Paris-bound correspondence and photograph it, shrinking it and sending the film—an early version of microfilm—by pigeon. Microfilm had in fact been invented a decade before, and its inventor was willing to fly to Tours by balloon with the requisite equipment. Film rolled into goose-quill tubes then was tied by silk thread to the homing pigeons.

In all, sixty-six balloons flew out of Paris during the siege, including the one that brought Gambetta out of Paris, in a failed attempt to organize new armies to come to Paris’s rescue. Nearly one hundred thousand messages would make the return trips. Hundreds of pigeons gallantly served.

On September 25, Manet wrote Suzanne that a balloon carrying letters was due to leave the following day and that he had been promised that his to her would be on it. He sought to assure her that, although “it is still impossible to make firm predictions, . . . Paris is tremendously well defended. There are now four hundred thousand armed National Guardsmen, without counting the Garde mobile and the regiment. If the provinces came to our aid, I think we could get the better of the Prussians.”

He also assured her that he was in good health, although he could not deny that the siege was beginning to pinch. “It’s true that we can’t have milk with our coffee now; the butchers are only open three days a week; people queue up outside from four in the morning, and there’s nothing left for the latecomers.”4

That was September. By October, smallpox had broken out, and food shortages were becoming more severe. Edmond de Goncourt went to get a card for his meat ration and noted that “horse-meat is sneaking slyly into the diet of the people of Paris.” Milk was available only to children and the sick, and by November, Manet recorded that “horsemeat is a delicacy, donkey is exorbitantly expensive, [and] there are butchers’ shops for dogs, cats, and rats.” Later that month, Geneviève Bizet remarked that although she had “not yet eaten cat or dog or rat or mouse . . . I shall taste donkey for the first time today.” And late in the year, Goncourt visited Roos’s, the English butcher’s shop on Boulevard Haussmann, where he saw “all sorts of weird remains. On the wall, hung in a place of honor, was the skinned trunk of young Pollux, the elephant at the zoo; and in the midst of nameless meats and unusual horns a boy was offering some camel’s kidneys for sale.” The butcher, much to his own irritation, had gotten less meat out of Pollux than he had expected.5

Manet and his colleagues may have bravely put up with deprivation, but working-class anger was soon boiling over. News that the remaining portion of the French army (under Marshal Bazaine) had surrendered at Metz, along with rumors that the government was making peace overtures to Bismarck, erupted in late October when the working-class battalions of the National Guard stormed the Hôtel de Ville and set up an insurrectional Commune. Goncourt, who was present on the Rue de Rivoli near the Hôtel de Ville, observed that “on every face could be seen distress at Bazaine’s capitulation, . . . and at the same time an angry and rashly heroic determination not to make peace.”6 This insurrection did not last, and soon bourgeois elements of the National Guard put an end to this early version of the Commune. But tensions between the government and the working classes remained, only to erupt far more bloodily in the spring.

Perhaps unexpectedly, Berthe Morisot and her parents decided to remain in Paris during the siege. Writing to her sister Edma in Brittany, Morisot told her that she had made up her mind to stay “because neither father nor mother told me firmly to leave,” and she did not want to abandon them. And so she remained in besieged Paris, where life was dull if not at present dangerous, and with militia quartered in their studio, which prevented her from painting. The house, she wrote, was “dreary, empty, stripped bare.” News of Prussian atrocities upset her, and she was suffering from nightmares. Worst of all, she had heard nothing of their brother, Tiburce, who was fighting on the front. Yet by September 25, she wrote Edma, “Would you believe that I am becoming accustomed to the sound of the cannon? It seems to me that I am now absolutely inured to war and capable of enduring anything.”7

In mid-September, Edouard Manet and his brother Eugène paid the Morisots a visit, to see how they were faring. Both brothers clearly admired Berthe Morisot, but it was the unmarried brother, Eugène, who would soon begin a gentle courtship, which in time would lead to marriage. For now, he told Morisot very calmly “that he did not expect to come out of [the war] alive.”8

Early on, Edouard Manet’s friend Edgar Degas joined him in the artillery, where both served as volunteer gunners, while the other Manet brothers, Eugène and Gustave, along with the painter Antoine Guillemet, joined National Guard battle units and were waiting to go into action. But “a lot of cowards have left,” Manet reported, including Zola and Fantin-Latour. “I don’t think they’ll be very well received on their return,” he added.9 Zola, who married his mistress as war approached, had headed south to Marseilles with his wife and mother as the Prussians closed in.

Another who was avoiding military duty was Claude Monet, who hung around Le Havre until November, when it became obvious that he would be drafted if he didn’t get out of France. Sometime that month he took a boat for London, with his wife and son soon following. There he met up with Pissarro, whose house in Louveciennes had suffered greatly under Prussian occupation. Prussian soldiers had trashed the paintings that he and Monet had stored there, with Pissarro’s losses by far the heavier of the two.

This London stay proved valuable to Monet, for it was there that he made the acquaintance of art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel, who also had fled France to England to escape the war. Durand-Ruel expressed an interest in acquiring some of Monet’s paintings and soon would become a pivotal figure in Monet’s career.

While Monet remained in safety, on November 18, his friend and benefactor, Frédéric Bazille, was killed in action, leading an assault on a German position. He was twenty-eight years old.

By year’s end, suffering and deprivation within Paris had become unbearable. Edouard Manet, who by now had traded in his position as a gunner for that of a cavalry officer attached to the general staff, reported that there was little to eat and no more coal. Trees, house shutters, theater seats, and anything burnable were being chopped up for firewood, while the weather was growing increasingly frigid and smallpox was rapidly spreading. He wrote Suzanne, “I think of you all the time and have filled the bedroom with your portraits.” “Paris is deathly sad,” he wrote Eva Gonzalès that same day. “We have had more than enough.”10

That December 5, Alexandre Dumas père died in his son’s summerhouse in Normandy, surrounded by his son’s family. He died quietly, leading George Sand to write, “He was the genius of life; he has not felt death.” But Maxime Du Camp wrote, “He died during the war, clinging like so many others to illusive hopes, and believing that victory must revisit the French camp.” Du Camp added, “He did not see Paris capitulate, nor the Commune, for the Gods loved him.”11

Following a climactic pounding on Paris administered by Prussia’s long-range siege guns, the French shuddered and at long last capitulated on January 28, 1871. “There was no way we could have held out any longer,” Manet wrote his wife.12 Hastily called elections quickly followed, in compliance with Bismarck’s requirement for a legal authority to sign the peace. Thanks to France’s rural voters, who constituted a majority of the electorate, the election returned a government heavily tilted toward advocates of peace, law and order, and monarchy. Adolphe Thiers became chief executive of this French Republic, which had all the appearances of being temporary.

The peace treaty required France to hand over Alsace and Lorraine as well as pay a huge war indemnity, accompanied by German occupation until

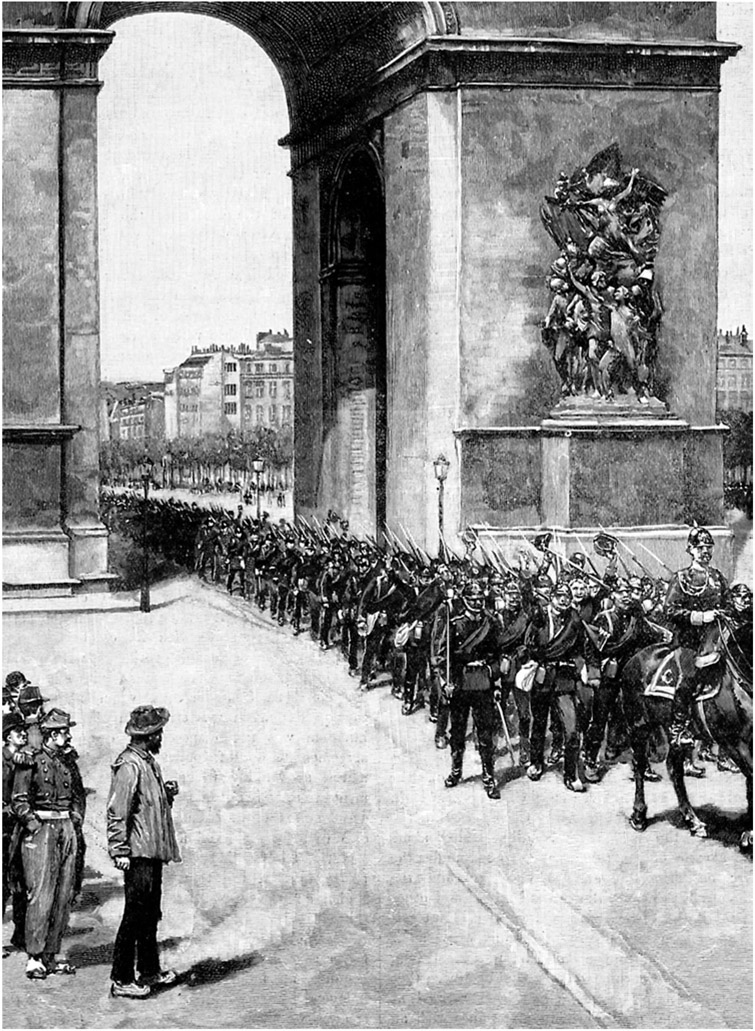

Prussian troops enter Paris through the Arc de Triomphe, 1871. © Lebrecht History / Bridgeman Images

the indemnity was paid in full. In addition, Bismarck insisted on a chest-thumping German victory march down the Champs-Elysées. But especially appalling to the French was Bismarck’s thumb-in-the-eye pageantry arranged for his king, Wilhelm of Prussia, who now arrived on the scene to declare the birth of a new German Empire—and his own imperial status—from the Hall of Mirrors of that most French of all palaces, Louis XIV’s Versailles. “This really marks the end of the greatness of France,” Edmond de Goncourt wrote sorrowfully, responding to news of the event.13

In the meantime, with the future of the new Republic in doubt, the poor of Paris—simmering under the humiliating capitulation to Prussia as well as the threatened return of monarchy—suddenly erupted. They had not done well under two decades of empire and the Haussmannization of Paris, and they were more than ready to take affairs into their own hands.

For the most extreme, this meant burning the house down, and before long, an array of Parisian structures—including, most symbolically, the Tuileries palace and the Hôtel de Ville—went up in smoke, even while members of a new Commune struggled to establish their own more equitable government. But Thiers, who quickly removed his government—and its army—to the safety of Versailles, now prepared to fight the Commune and Communards.

After a wrenching war with Germany, the French were now at war with each other.

Louis-Napoleon remained comfortably imprisoned for several months in King Wilhelm’s summer palace, where he—and Eugenie—negotiated until the last for a return to power. Yet having little to bargain with, he and his proposals barely warranted a shrug from either Bismarck or Wilhelm, while for their part, the French seemed little interested in having either of them back.

On March 1, the newly elected French assembly officially deposed Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte as emperor and declared him responsible for the nation’s ignominious defeat. A few observers, including Maxime Du Camp, begged to differ. “The nation,” he wrote, “had her fate in her own hands and this is what she has made of it.”14 But for the most part, Louis-Napoleon would go down in history, especially in French history, as the cause of France’s humiliating defeat to Prussia.

Released from captivity, the former emperor joined Eugenie in the Georgian country house near London that he had presciently bought several years earlier, presumably as a bolt-hole if escape proved necessary. Remembering his youth in the court of his uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, Louis-Napoleon had always mistrusted how long his glittering empire would last.

There he remained until his death two years later, following several operations. His son, the Imperial Prince, would die six years after that, as an officer in the British Army fighting in South Africa.

Eugenie lived to the age of ninety-four, spending much of her time at Cap Martin on the Mediterranean. Yet she sometimes returned to Paris where, strangely enough, she chose to stay at the Hôtel Continental, overlooking the Tuileries gardens. From her well-appointed rooms there, she could hardly avoid seeing the vast empty space where her palace, the Palais des Tuileries, once dominated the gardens’ eastern end. The palace had disappeared, burned and gutted during the Commune uprising of 1871 and swept away by the Third Republic, which wanted no imperial memories to contend with.

A crusty and energetic old lady, the former empress was as tough in old age as she had been in her youth. Instead of indulging in delicate wistfulness, she simply remarked to her interviewer, Maurice Paléologue: “Heavens! How dearly we paid for our grandeurs!”15

Yet those who paid the highest price for the empire’s grandeurs, and for their own dreams, were the poor of Paris, whose attempt to create an ideal Republic—the highly contentious but socially conscious Commune—came to a violent end that May.

Following the opening shots of revolt, members of the official French government, under Thiers, raced for the safety of Versailles, well beyond Paris’s massive walls. Thiers, who had been responsible for building these fortifications in the first place and well knew their strengths and weaknesses, proceeded deliberately. Finally, after a lengthy cannon bombardment of western Paris and the capture of several of the fortification’s nearby fortresses, government troops poured into the city.

Unquestionably, the Communards found it difficult to build and defend their barricades in the new Paris that Haussmann had created, with its wide and straight thoroughfares on which troops could march unimpeded. But one unforeseen consequence of Haussmann’s slum clearance was the removal of Paris’s poor from the center of town to its outskirts—to Montmartre, Belleville, and all those impoverished communities around Paris’s periphery. Here, in their home territory, the Communards put up a fierce fight.

During that terrible week in May since known as “Bloody Week,” reprisals triggered reprisals as fury and despair escalated. Seething at the brutality of Thiers’s troops, Communards destroyed his mansion on Place Saint-Georges (9th) and then set to work on other monuments linked with the ancien régime and both empires. Soon it seemed as if all Paris was burning, and the killing still went on. By the week’s end, only a few pockets of resistance remained—the largest being the famed cemetery of Père-Lachaise, in the twentieth arrondissement. Here, a macabre nighttime gun battle took place among the tombstones, until by morning the remaining Communards had been driven into the cemetery’s far southeastern corner. Lined up against the wall, all 147 were shot and buried in a communal grave. This site, now a place of pilgrimage, is marked only by a simple plaque dedicated “Aux Morts de la Commune, 21–28 Mai 1871.”

At least twenty thousand Communards and their supporters died—a figure that dwarfs not only the Communards’ own well-publicized executions but even the grisly body count of the Reign of Terror. This, and a Paris filled with smoking ruins, was the legacy of these terrible weeks and months.

Edouard Manet left Paris and rejoined his family soon after the capitulation but returned during the height of the Commune uprising, where he sketched some of the horrors he had witnessed: government soldiers firing at close range on a barricade (“The Barricade”) and a body lying at the foot of a toppled barricade (“Civil War”). Manet was quick to sympathize with human suffering but was no Communard. Instead, he was an ardent supporter of a liberal republic, who was appalled by the violence and repression practiced by the government troops but who was equally unnerved by the Commune.

Sarah Bernhardt was also sympathetic to the downtrodden of Paris (“This war,” she wrote afterward, “had hollowed out under their very feet a gulf of ruin and of mourning”) but termed the Commune “wretched.” She had nursed her wounded soldiers right through the Prussian bombardment but left immediately after the armistice, retrieving her mother and family from Germany (where they had inexplicably landed) and taking refuge just outside of Paris as it went up in flames. Venturing back after the Commune was crushed, she noted in her memoirs that everywhere one could smell the “bitter odor of smoke.” Even in her own home, everything she touched left an unpleasant residue on her fingers. “What blood and ashes!” she wrote. “What women in mourning! What ruins!”16

Victor Hugo, for his part, heartily approved of the Commune, at least in theory, but was leery of its extremism. Leaving Paris in a hurry just as the Commune burst into being, he fled to Brussels and then to Luxembourg, not returning to Paris until the worst was over.

Louise Michel, on the other hand, gloried in the Commune uprising, mobilizing the women, organizing day care for the children, and fighting on the barricades. After the last of the Communard resistance was shot down, Michel was arrested and brought to trial. There she defiantly dared the court to kill her. “Since it seems that any heart which beats for liberty has the right only to a small lump of lead,” she told the court, “I demand my share.”17 Instead of granting her wish, the court sentenced her to what it probably believed was a slower form of death—deportation to the harsh penal colony in France’s South Pacific islands of New Caledonia. There she remained, defiantly surviving. Paris had not seen the last of the woman whom her antagonists derisively called the “Red Virgin.”

Berthe Morisot remained in Paris until the outbreak of the Commune, when she joined her sisters in Cherbourg. There, Edouard Manet wrote her after his own return to Paris. “What terrible events,” he exclaimed, “and how are we going to come out of this? Each one lays the blame on his neighbor, but to tell the truth all of us are responsible for what has happened.”18

It was an unusually generous view, and one not shared by many at the time—certainly not by Georges Haussmann, who had watched with horror as much of the city he had transformed was reduced to ashes. His response was to try to bring back Napoleon III and the empire. But the Third Republic—despite its rocky early years—rejected Bonapartism, even while it continued with many of Haussmann’s plans for building and rebuilding Paris.

After some initial hesitation, the new republic finished the Opéra Garnier and the Avenue de l’Opéra leading to it; completed the Left Bank’s major east-west artery, the Boulevard Saint-Germain; and continued to expand on Haussmann and Belgrand’s revolutionary water and sewer system. At the same time, the new republic went to work to repair the damage inflicted during the Commune, most especially by rebuilding the burned-out Hôtel de Ville and the Palais de Justice.

France quickly paid off its war reparations, the German occupiers went home, and within a miraculously short time, Paris was back in business—ready to host a new epoch in creativity, the Belle Epoque. Out of the ashes of defeat would come Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Matisse, and Picasso, while composers such as Debussy, Ravel, and Stravinsky would rock the musical world. Zola would provide literary fireworks, and Proust would dip his pen into his delicate teacup of memories, while that magician of iron, Gustave Eiffel, would defy a host of naysayers to build a tower that would identify Paris for all time.

Instead of death, there now was dawn—along with another chance to define and redefine Paris, city of dreams.