4.

Backstage.

All about the back stage, down and down, ran Edith in her grey gown. I am Edith Theatre, I told myself. I know all monsters. I know the truth of goblins, I eat specters for dinner, I am fire and plague, I am the spell caster, the story maker. I am the spider, I am the fly. I am dark and deep and hell all over. Days go by and my hair is unbrushed. Where I go, I leave a trail of blood. I bite my nails. I am the playwright.

Yet no matter how I reassured myself, still I felt so uncertain. A new mother, a new mother and an Utting—what could that mean? Was I to be ignored or worried over? Unstitched or stitched up? How would Father behave toward me, with a new woman busying him? A woman from out there, from beyond the theatre. We never let people from out there come in here, not without permission. And yet, without my knowledge, permission had been granted.

I stood for a while at the stage door, looking out into Chantry Road as if it might provide some answers. Mr. Peat was in his little office, which guards the outside door. Mr. Peat is the Cerberus of the back stage. He always knows who is in and who is out. None may enter or exit, save through him. He swears like a sailor and smokes like a chimney and sits in his box with all his keys, watching all, coughing and swearing and tugging at his forelock, and though he insists the theatre is a childish business, still he loves it well, and guards it with great seriousness. Beyond him is the world.

Mr. Peat taught me all the worst words I know, schooled me in them as if they were precious: bugger and shiteabed and quim and gonads. He taught me, too, of Norfolk places, of the watery Broads and the long beach of Holkham, of the holy place of Great Walsingham, where long ago an Anglo-Saxon woman called Richeldis de Faverches dreamed that the Virgin Mary came to her and told her to build a replica of her holy house in Nazareth, and she did and somehow she knew exactly how it looked. It was a miracle. And there in Walsingham they also have a vial of the Virgin’s milk. It is an old story like the Norwich tale of Maw Meg. But Mr. Peat was not in the story vein that early afternoon.

“Should you be here alonga me, Edith Holler?”

“I may be if I choose it.”

“And not with your aunt in wardrobe?”

“I am getting ready for my play.”

“That’s not due yet. About yer play, Edith Holler, truly is it set in Norwich?” (Narridge, he says.)

“It is, Mr. Peat.”

“A play in Norwich! Never known the like. Is it right, do you think?”

“Nothing is righter!”

“Plays are on London, on Paris, on Italian foreign places. No play as ever I heard was set in Norwich.”

“Then it is high time.”

“Norwich. It don’t seem right. Makes me uncertain.”

“Father is to marry, I am told.”

“Heard the same myself. I am sorry, gearte.”

“Oh, Mr. Peat, have you seen this new woman?”

“Might of.”

“What’s she like?”

“You’ll larn soon, I reckon.”

“I’m that worried, Mr. Peat.”

“Run along to your aunt now. But here first, chidder, afore you go take this then. Have a coshie. Suck on that. Do you good, that will.” He gave me a piece of candy-striped Cromer rock, which he hands out now and then on special occasions. “You may, when she has taken her place, if you need it, come alonga me of an afternoon and sit here beside Old Peat and we’ll talk of things and that may be a help to you. In the coming times.”

“Oh, Mr. Peat.”

“Get you gone, gearte.”

I did not ascend to my aunt Nora, rather I went to the scenery dock, to visit a certain canvas. But there was no progress since I had last come, which was only the day before, still what a sight.

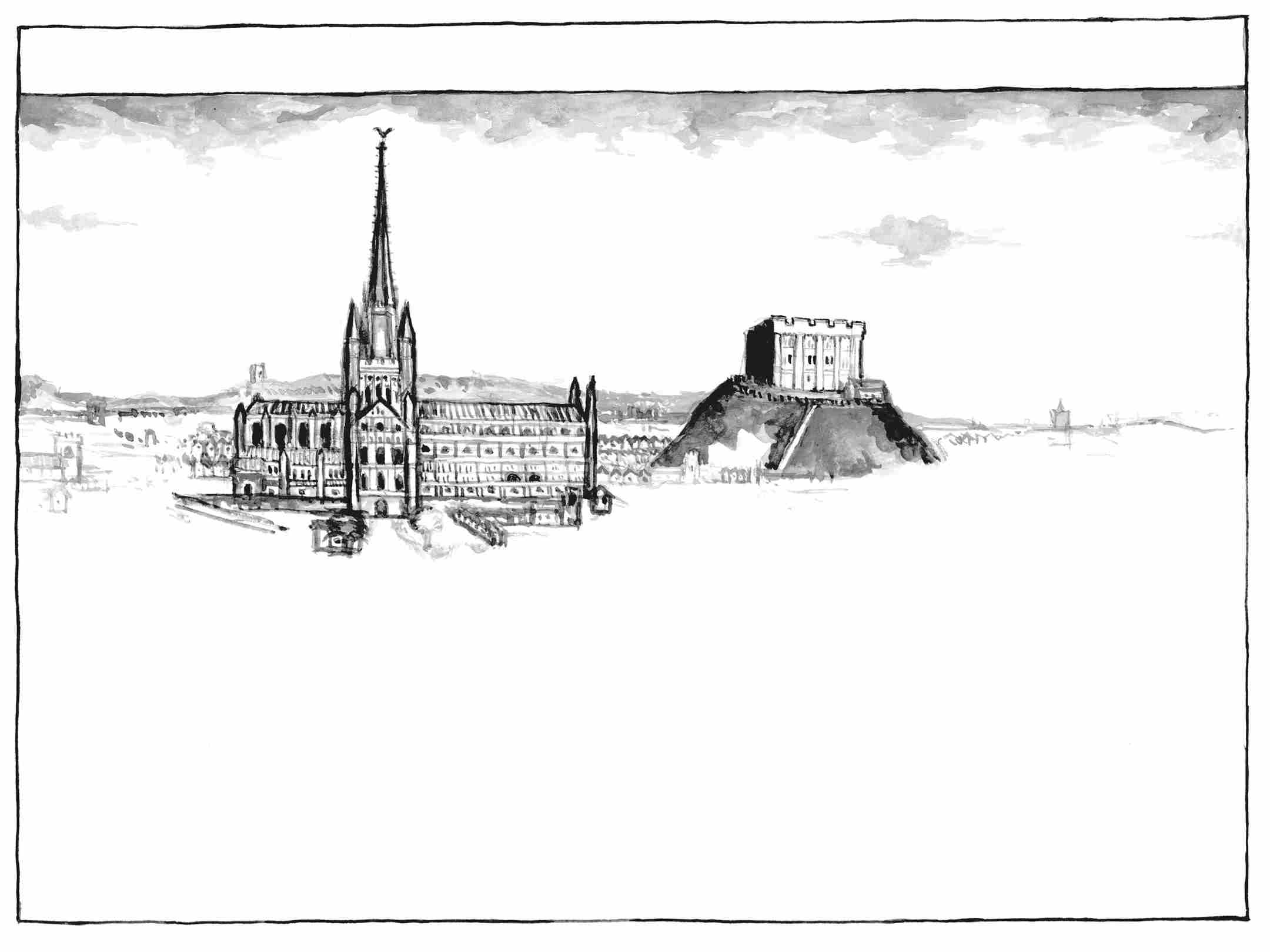

Here was Norwich, where we make our scene. Norwich in the fourteenth century. Gone are all the Georgian places, gone are the Victorian ones. No streetlamps and certainly no trams, nor any Beetle Spread factory neither. “We are going backward in time, pull up the ghosts, let the past leak out at last. And see that you are now upon ancient Norwich land.”

Look closer, though. You know this place. There is the castle and there the cathedral. You know your way around by those ancient beacons, though it is so very long ago.

On the back is painted Act 1, Sc. 1, True Hist M Meg.

And that is proof enough. It is a great good thing.

“Hello!” I called.

But no one was there. Where were they all gone? As if Norwich were deserted.

I felt as if I were saying good-bye. Good-bye to everyone. I ran all about, not settling in any one place, but in a fidget everyroom. Upsetting uncles and aunts and disturbing some acting cousins, who were practicing their fencing scenes with Mr. Atkins the fight master. I watched them awhile but ran along again. Ignoring their calls that Miss Edith must to the wardrobe.

I called in on Miss Tebby, who sat dependably in her room of paper. Miss Tebby is the theatre prompt, and her little office is a nest of playscripts. She has them all, and all are up to date.

“Miss Edith, up again!”

“Can I hide here?”

“Yes, my dear girl, come in. Make yourself at home.”

“I thank you!”

“In truth, I am glad you are here. I’ve been wanting to ask, is all well with your family?”

“Well enough I suppose, Miss Tebby.”

“And your father? I worry about him. I have of late had to feed him several lines, it’s not like him at all. Have you noticed anything different?”

“Yes Miss Tebby, he is to marry!”

“He is? Indeed! Ah well, perhaps that is his distraction then.” She knows the news well enough, I can tell. Miss Tebby is a terrible actress. “And you, are you well?” Her voice is ever quiet, always a whisper. Miss Tebby, of course, has never in life been heard to her raise her voice. She needs a quiet voice, so that when the actors forget their lines, she from her little trap at the front of the stage just behind the footlights may peek out and pass on to the actors the words they have temporarily misplaced, in a voice so perfectly quiet that the actors may hear it but the audience may not.

“Quite well, I thank you.”

“Why then do you shake so, girl?”

“In truth, dear Miss Tebby, I’m supposed to be being fitted for a dress to meet Father’s new wife, and I am afraid—for the woman is an Utting you see, Prompt.” Miss Tebby, owllike, prompts us all, if we call her, very quietly, by the name Prompt.

“I am a girl of twelve,” prompts the prompt, feeding me lines, brushing my hair. “I am not an adult yet, though sometimes I pretend to be. I am the sheltered daughter of a difficult man. I have no power here, and so I will do the best if I observe what small rules are given me. I should keep to my own floor and my own rooms—up where it is lighter and the air is better. I have written a play, a good play some say, especially for my age, drawing upon folklore and history. I am doing well and should walk carefully now. I am better again after a long decline. I should be good to the new mother, and give her every chance. Let us hope she will be a blessing to me and let me welcome her properly.”

“Who are you to tell me such things?”

“Prompt mistress.”

“You don’t have any lines at all.”

“I have all the lines, every single one of them. Now go as directed. Arrive at your station. Get back in the script. Where are you meant to be, Miss Edith?”

“In the wardrobe.”

“Then find your place.”

“I’m leaving.”

“Yet wait a little moment, my Edith child. May I tell you, though it is not proper for such as I to have opinions: I love the play. My favorite is the line: ‘You look at me, you people of Tombland, as if I had six legs, as if I scuttle in blackness, you see me not as the woman that I am, but as a shadow in rough human shape, a creature of darkness, yet I am a woman still, I am one of yours, though you shun me so!’ It makes me think of myself, of the actors when they take me for granted. Oh, Edith, that is very grand. It will be a big success, I think.”

“Oh thank you, Miss Tebby! I think so too.”

“To the wardrobe, then, clever Edith. Be strong.”

But I did not go to the wardrobe that uncertain afternoon. Instead, I found me wandering the dressing rooms, taking the east stairway down as the west stairway is currently forbidden on account of it not being safe. The dressing rooms were where all our bodies are wont to loll when they are not required upon the stage. Ah, I love them so—all the actors I mean, our people, who rush to pat Edith upon the head, to hug and stroke, to pet me and lift me up in a whirl, or to come straight out and kiss me hard upon the lips, to dandle and to fuss over me and also to chivvy me along. Such a tactile nation. All our people in their undergarments, slouchy and smoking, in their peace before performance time, before their hearts start beating faster. Yet how fast mine thrashed as I weaved myself in among the pretending people, all very busy with a costume call for Titus Andronicus, in and out of their dressing gowns, so free in their skins.

Aunt Agatha Wilson, in her own skin, came to me direct.

“Miss Edith, I have read the play, I think it quite beastly. Properly beastly, you understand me. I think, especially, that there is a part for me here. The one called Mawther Meg. I’ve been looking for a part like this. See me now, observe me, darling.” She stood up as tall as she might and put on a ghastly visage, and proclaimed: “ ‘Who is it that comes knocking at my door? Who is it that disturbs Lone Meg? No one visits me. I live in silence, yet is there a sound now? There it is again! The knocking! It is the noise of company!’ ”

She was quoting words by Edith Holler.

“It is lovely, Aunt Agatha. And well done. I must along now.”

“You will consider me,” she said, offended. “It’s all I ask.”

“Of course.”

“I’m glad to see you up again, my darling.”

I am so fond of Agatha, but I’m not certain she has that about her that says Maw Meg. She retreated to her dressing room, closing her door behind her.

I wandered the passageways and followed the noise of men talking loudly. My lesser acting uncles—that is, my actual uncles, who may as well be called Polonius or Albany, Trinculo, Lepidus, Hastings, or Leonato, but were christened Gregory and Thomas—were together in the greenroom, drinking. Father’s two acting brothers believe most of all in payday and beer and hot suppers.

“Edith, up again! Edith Holler the playwright!”

“I have read your play,” said Uncle Gregory. “Can’t say I understand it entirely. Is it right for a woman to be writing plays, and a child at that? It feels an indulgence. Edgar certainly has gone too far this time. Children missing, Edith? You’ll start a panic. And lord knows what Edgar’s new woman shall say! Quite the scandal.”

“By which he means, Edith, he doesn’t like his part.”

“I am an old building, wattle and daub!” said Gregory. “Seventeen lines. ‘I am thin timbers and leaking roof, holes there are in and out of my walls, by beetles have I been gnawed and gnawn.’ A building! A ruin!”

“I am quite happy with my role. Robert Baxter, the mayor of Norwich.”

“Thank you, Uncle Thomas.”

“There may be room, perhaps, for another scene between him and Mawther Meg. I can see it clearly. I wonder if you’ve quite considered all the possibilities of this part. A romance, or, alternatively, a murder. We could talk about it. Perhaps the mayor might disappear a child or two himself.”

“Oh, Edith,” said Uncle Gregory, lifting up my chin, “you look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

“Yes, Uncle.”

“And there are other looks to be had.”

“Yes, Uncle.”

“Edith, you know you must go to your cloth aunt,” said Gregory. My aunt Nora was his wife, but they were not on speaking terms, not since Gregory got too close to an actress from Bungay (Norfolk-Suffolk border) and was found in her dressing room without any cloth upon him. Ever since, my uncle Gregory seems to have come unstitched rather himself. Nora has forbidden him her presence, and how neglected his clothing is now, it droops and has patches, there are always loose threads. Even when some third party presents him with a new costume, it is always a disappointment, always shoddy and awkward. How threadbare his performances have been of late. His daughter, my cousin Claire—who might be called a very fine pair of scissors in her late twenties—keeps her father up to date. She snaps at him all the latest news from the wardrobe department.

“Go now, Edith. New days are coming.”

“Yes, Uncle, I have heard. What’s she like, Uncle?”

“You shall see quite soon enough. Time to grow up, Edith. Be a Holler, won’t you?”

“I try.”

“Up you go, then, don’t make a fuss.” Uncle Thomas pushed me gently from the greenroom and closed the door.

“Miss Edith!”—someone calling me along the passageway. I knew that voice and it signified misery for me. “Miss Edith! Miss Edith, dear Miss Edith out in the world!”

Mr. Mealing on the hunt. I called him Mealy on account of his skin like cold pork and all the small blasts of redness thereabout. He slinked and slurked about the theatre and made his small sounds. He called himself playwright, but what little dramas he wrote were all bland things about drawing rooms in London—though he had never been in such environs—and with not a hint of magic about them. I avoided him at all times. He liked me, Mr. Mealing did. He used to pinch my cheeks, but more recently he had taken to pinching my thigh. I detested the man and fled him always.

“Is it Miss Edith there? Holloah, Edith! Do come and read my new play, shan’t you? I have read your play, too, and I have some advice for you. Let me escort you to the wardrobe, shan’t you? You and I?”

No, I bloody shan’t. On I ran. And down, down and down, where there is ever less light.

There are so few private places in a theatre, when you think about it. You may say the dressing rooms, but they are mostly shared and a stage manager may burst in any moment without knocking and call it business. But I have a little place, down underneath the dressing rooms it is, in the quiet bowels of the theatre, a place I call my own.

Down I went—I held on to the rope banisters, down and down, into the bowels. A new sign there:

DANGER

no more than 2 persons

on the stairs at any time

It may be helpful, for those who are not acquainted with the theatre as I am, to think of the backstage side as a great ship. All that wood, all those ropes. And to think of the stage, ever scrubbed, as the deck, and below deck is the understage, which goes down many floors. Unlike the ship, however, there are no portholes, so all gets darker and darker the deeper you dare go.

To get to my private place I must first go to the furnace room, and within the furnace room is the backup furnace, which is never used and so is always private. It is there “just in case,” like an understudy, and it has laid cold ever since it was put in, so I have taken it for myself. I climb in there and close the metal door and light a candle and then I have my peace. No one knows I come here; Father would be horrified and forbid it. I can almost hear him: “Suppose it was lit, Edith. And you inside?”

Here I keep my own cardboard theatres; here I play God with the people of card. It is proper to call them toy theatres, but that never sounds right to me. They are more than toy, the word toy condemns them, it disapproves, it trivializes. They are very dear to me, they are essential.

No one else knows of my visits here, not anymore, not since my friend Elsie Mardle left us. I play here alone, when I am well enough, with all the card booklets I have, and Father often orders me new ones, which are sent all the way from London, from Pollock’s Toy Theatres Ltd., 11 Kendal Place, London W1. Though I am twelve, still I love them yet. Here is my great populace when the theatre above me is too busy. I have everyone here: I have witches and trolls and soldiers, I have even Napoleon (who was an emperor and died on an obscure island, though he was more famous than anyone in the world). Sometimes I go about with Napoleon in my pocket, and then I do feel a bit emperor myself.

But the playing no longer comes right since my friend Elsie Mardle left. Elsie worked with Aunt Bleachy and scrubbed herself raw, but at the end of the day we would find each other and then we were together and that was always enough for us. She had a short-tempered father who worked at Utting’s and a mother, quite stained red, who washed clothes in the Wensum, but was in with the gin to keep herself warm. I found her that first time, my Elsie girl, shivering by the working furnace, ill like me, and I gave her cake—pocket cake I call it, the food I stuff in my pockets when I set about exploring—and she took it and she ate it. And I kept finding her here and I kept getting her some food.

Most of all we would play for hours at my card theatres, right here in the second furnace, lolling together, our feet touching. There we would perform the whole of The Corsican Brothers or The Children in the Wood or else Daughter of the Regiment, also Harlequinade, all of these actual toy theatre plays with cardboard figures and changing scenery. We followed the instructions in the booklet and read the lines that were provided there and gave card much voice. How we have wept, we two, at the death of Louis de Franchi in The Corsican Brothers, though he was only ever a piece of colored card, and how we both agreed that the most moving of all the cardboard populace was the figure of the shade of Louis de Franchi, his face as white as paper and with a devastating red wound upon his chest. For to die in cardboard is still to die.

But one evening we lost time as we enacted the cardboard life of Blackbeard the Pirate, and by the time the dreadful end was reached and Blackbeard fell into the angry ocean, we opened the furnace door and heard that the evening’s business on the stage had begun, and it was much later than we thought. Elsie’s terror now was real as she went miserable into the night, and no matter that I put a sunny country landscape in the little theatre slot, outside it remained stubbornly dark.

She was so badly scolded for being home late that she missed two days of work and was nervous to play with me afterward, so bruised she was. “It goes different with me, Edith. You may have your tales but what use are they to me? Look what they done to me!”

A short time later, Elsie was taken from me. She was given new work in the Beetle Spread factory, and I must let her go. Will you write, Elsie?

“Surely, Edith. When I have the mind for it.”

I could not wait to get that letter. What a thing to have a letter.

Yet no letter came.

And that day I found that I had no patience for cardboard people, for they gave no hint at the new mother, nor did they show me my play which had grown greater than cardboard and was now canvas and would soon be made flesh. I put them down. I am different now. I have stood naked upon the stage. I am a new Edith without time for card. I am not flat, I am full and solid and real. I blew out the candle. Black went everything. And it was the end of the world and I was dead and buried. And yet. Breathe, Edith, breathe. Count to ten and open the latch. I did, so quietly. Back in the furnace room. Me and the warmth—but then the outside door opened and I wasn’t alone anymore.

“Miss Edith! Miss Edith, here you are at last. Whyever do you hide in such a sooty chamber?”

Mealy in my private place, spoiling everything.

“I must get out, you are in my way,” I cried.

“Miss Edith, Miss Edith,” he says to me coming very close indeed, he always makes the first vowel of my name very long, Eeeeeeeeeeeeeedif, he says, like he’s breathing all over me with it, or like he’s stroking it or taking possession.

“Yes, Mr. Mealing.”

“Do, dear Miss Edith, call me Oliver.”

I would rather die.

“You say nothing, Miss Edith.”

I did not indeed.

“Nothing will come of nothing, Miss Edith. You know that, I think.”

“Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave my heart into my mouth,” I said, my thanks to Cordelia.

“I do not want your heart in your mouth, Miss Edith. That would be a strange sight indeed. I want you, rather, in an elegant summer dress that I have seen in a shop on Rampant Horse Street. Very light material.”

Go away, go away, Mealing. I don’t want you here.

“Miss Edith? Miss Edith!” I heard Great-Aunt Flora calling me outside.

“I must go, you see.” And I shoved past him. Out into the understage. I shut the door on him, too.

A very short play

Enter Mealing.

Exit Mealing.

Finis.

“Miss Edith! There you are!” huffed Flora. “You run me ragged. Come here at last!”

Flora, it’s Flora. Ignore her, ignore her. Run, Edith. Run.

Across the understage to the puppet workshop and dear Mrs. Stead. Mrs. Stead would surely hide me.

“Miss Edith!” shouted Flora. “You only make it worse for yourself! You’ll do yourself an injury and I’ll be blamed for it! If you are sick tomorrow it’s hardly my fault.”

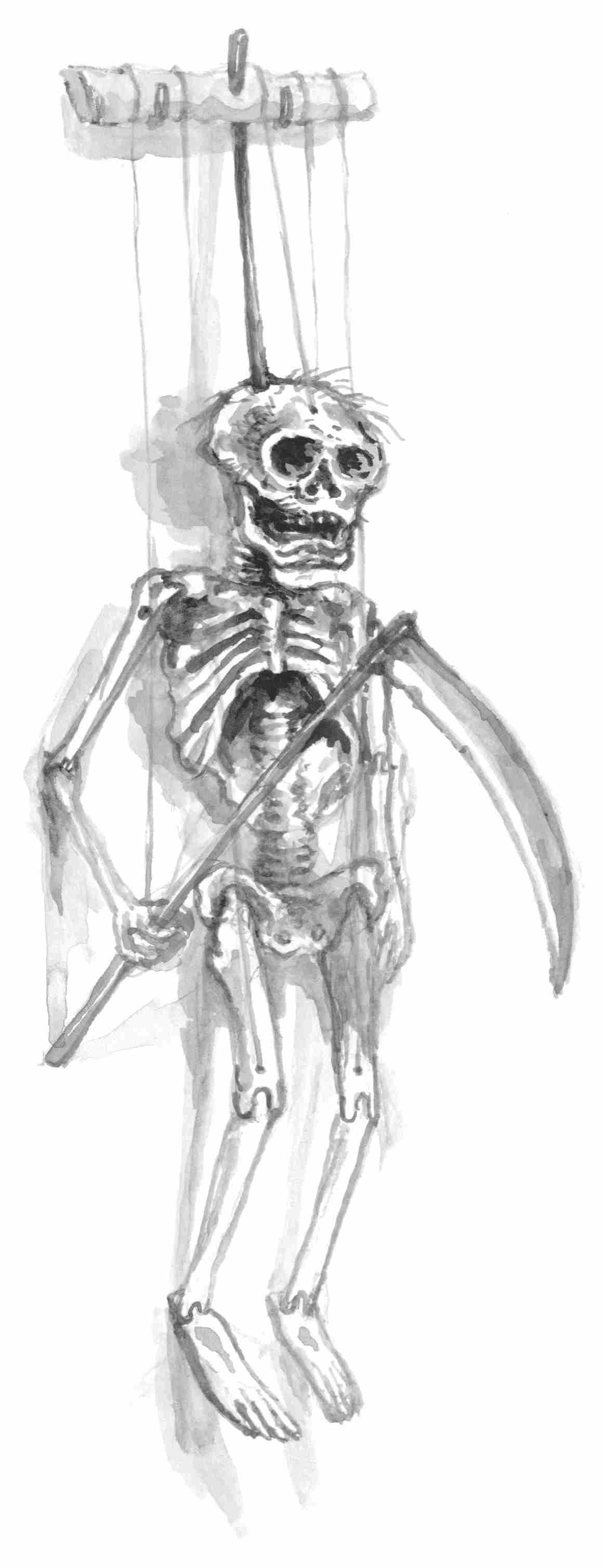

But there was a puppet hanging on the workshop door, and that puppet was Death, which meant that no one was to go in right then. I should have to wait until some other stringfellow was put up there, Pantalone, say, or Columbina or Mr. Punch, and only then could I make a cautious hallo, may I come by? Death means: keep out, Edith. And so I do.

“Miss Edith, come back.” Flora yet. “Where are you going? Don’t go down deep, I’ll not follow you there. You may not descend further. It is expressly against the law of theatre.”

Well, that was an idea then. I had no care for signs, had I? What could it matter a grey weight like me?

no entry, access forbidden

“No you don’t.” Mealy again. Mealy had sudden hold of me, just for a moment.

“Don’t touch!” I screamed. And pushed him away.

“Calm, Miss Edith. You must calm, none of your histrionics. There is nowhere for you to go, nowhere but Oliver Mealing.”

Yet there were other addresses, at least there was one close by. Inching away from Mealing, I hit against a wall, my back banged into a handle. A door handle. To the trap room. The trap room has two doors so that you may get from it right across the other side of backstage. The trap room is where the actors fall when the trapdoors in the stage are opened. It is a room of mattresses. A quiet place usually, but of a sudden its ceiling opens in certain places and people hurtle from the sky into it. That’s the place I went rushing into. I felt Mealy’s hand on me, but he was frightened, and he stumbled in the trap room’s darkness. Quickly I was behind one of the stacks of mattresses.

“Miss Edith? Miss Edith, where are you? Don’t be shy.”

Getting yet closer now. I changed my spot, hid behind the next stack.

“Meeees Eeeediiifff, ah you make it a game. I do seek you!” And the next.

“Meeees Eeediii . . . ah!”

Mealing had run into something, and that was what I needed. I’d worked my way round, and as quietly as I may, I was out again and on the other side of the understage. Left behind: Mealing, in the trap room, hurting.

strictly no entry

this area out of bounds

Now I could climb down farther yet, to the damp, dark land where the donkeys are kept and blind Mr. Leadham too. The donkeys pull the great wooden wheel that revolves the stage, or sometimes tugs great ships across it. I’d be safe in the deep dark so long as I was quiet. I could hear the donkeys, shifting in the ground, a little unsettled perhaps; no doubt they had heard me. I could barely see them in the deep distance, touched by the shyest puddle of light. Mr. Leadham keeps a lanthorn lit to calm the beasts, even though he cannot see himself. He gives them a little light from his particular small lanthorn, which always has a lucifer connected to it, attached by an old shoelace, so that he may never lose it.

“Who’s thar?” It was Mr. Leadham calling.

I kept very still.

“All right, my dickeys,” he said at last, “all right, Judy; down, Olive; steady, Old Alice. All is well, stop yer grizzling,” and the donkeys calmed.

I’d be good here, so long as I was still and quiet, so long as those upstairs ones didn’t come poking. I’d be fine now. Well done, Edith.

A flash of light, a match struck, and through darkness the face of Uncle Wilfred suddenly appeared before me, lighting his pipe. I let out a small scream. Uncle Wilfred is not generally to be screamed at; he is my practical uncle and since his childhood he has always been the maker of things. He has ever found a way of rendering Father’s ideas. If Father says a dragon, then Wilfred says twelve sheets of ply, some glass, dry ice, vermillion paint (at such a cost). He knows things better than anyone and can shape them into dreams.

“Who’s thar agin?” called Mr. Leadham.

“Is only me,” said Wilfred. “Me and Edgar Holler’s daughter.”

“Why’s the ickeny child down here? Not her place.”

“I shall see to it, old bor. Calm and quiet and all is well.”

Wilfred took me by the elbow and led me up the stairs.

“There’s going to be a new wife,” I said.

“I have heard but not seen.”

“How long have you known?”

“A week or two.”

“And you didn’t tell me.”

“Was asked to keep it dark. Besides which, I have not seen you.”

“She’s not from the theatre, she’s not one of us.”

“I do know it.”

“She’s an Utting!”

“I have heard that.”

“I should have been told. It’s not right.”

“You’ve been told now at least so be of good cheer. You’re to go along, Nora is waiting. Don’t cause grief. Is a celebration.”

“Is it?”

“It is and you have written a play, too, niece, and that is a celebration and all.”

“Did you like it, Uncle?”

“Not for me to say. But we shall do it, shan’t we.”

“Can I have everything that is in the script? Can I have all the ghosts?”

“You may have whatever you wish. Whatever is written, we’ll find a way.”

“How will you do them, Uncle Wilfred?”

“I was thinking, having read the pages, dirty clothes and rubbish. Can easily pick the clothes up from Norwich market, at the rag shop, tuppence a pound. Quite within budget. There, you see, is easily done. Is no great bother.”

“And they are very lonely, those orphaned clothes, and would not complain of the attention. They were hoping for a good home. Don’t you think so, Uncle?”

But he never answered, because a stagehand, a pleasant young fellow name of Hawthorne, came calling down the wooden stairs, not venturing deeper himself. “Mr. Wilfred, are you there below?”

“I am here, lad.”

“It’s Mr. Holler. He’s asking for you.”

“Thank you, Hawthorne.”

Wilfred obeyed Father’s call, he always did.

“Come on then, Edith. Up the stairs with you, hold on careful now. Watch your step, step over that one, that’s good. Do not come down here, Edith, it is not solid and you know it. And, Edith, good my niece, don’t cause strife.”

“Yes, Uncle.”

“Let me see you go along to Nora.”

There were the stairs up to the wardrobe, and there was the door with the baize over it to muffle the sounds. That is the door that leads onto the stage. I turned, I took the first two steps upward, but then I stopped. Wilfred went toward the stage and was gone. I took one more step, then turned and followed Wilfred through the door, and I was in the dark of the wings of backstage left. Slipping between the two giant barrels of stage blood, I banged into one and heard the deep liquid lapping inside. From there I could see Wilfred joining the actors. I could even see the vast back of Father. Normally I would run to him, though my uncles and aunts would try to prevent it. But not today, not with this news. Better to leave him. Better to consider the news all alone.

The door had shut silently behind me. Safe. Yet in a moment it opened again. There was Flora and Mealing beside her, and Miss Tebby. Mr. Collin there too.

“Miss Edith? Miss Edith? Have you got Edith Holler there onstage with you?”

“No, no, she’s not here.”

“She’s gone up to Nora,” said Uncle Wilfred.

“I’ve just come down from Nora,” said Mr. Collin. “She’s not there.”

“She’ll make herself sick again,” said Flora, “and it won’t be my fault.”

So then there was only one place left for me to go. To the other land of theatre. Every theatre is a house divided in two, the private side and the public side, and the two are separated by a great guillotine: The iron it is called, a thick iron curtain that closes the stage off from the public side. It is there for safety, to stop fire spreading. If there is a fire—and how awful a thing that would be—the whole of one side would burn to a crisp and yet the other would be safe, shielded by the fireproof iron. I often wondered how that would be, to be on the safe side but listening to the great burning of the other, the screams and the terror. I fear a fire most particularly, for if the theatre burns, what am I to do? I who must never leave the theatre or die of it.

The iron was down as I came trip-trap close to it.

I crept by the stage manager’s desk and through the pass door—and suddenly I was in a different land, with different rules.