If you do not make these payments as you are obliged by promises and pacts, you will have to excuse us that we also do not obey the pacts between ourselves and your commune.

JOHN THORNBURY TO THE CITIZENS OF SIENA, 1375

• • •

It is hardly unreasonable to expect to be paid, whatever sort of knight you are. Being a mercenary, however, is more than just a matter of taking pay. If you are willing to take money from any employer, and to change sides if the money is right, then you are a mercenary, and there are some good opportunities awaiting you. This is a career for professional soldiers, and you need to be aware that you are as likely to gain notoriety as fame. If you are a German knight, above all from Swabia or the Rhineland, then the temptation to go to fight as a mercenary in Italy is particularly strong.

You might expect the experts to regard this kind of career as the contradiction of all that is chivalric, but Geoffroi de Charny is far from hostile to it. He discusses knights who leave their homeland and go to Italy, and his conclusion is that they deserve considerable praise.

Through this they can see, learn and gain knowledge of much that is good through participating in war, for they may be in such lands or territories where they can witness and themselves achieve great feats of arms.

Geoffroi’s warning is that those who do take this course should not be tempted to give it up too soon, taking a quick profit. He says that even when the body can do no more, your heart and will should drive you on.

Origins

A career as a mercenary is particularly tempting if you are not quite from the top drawer. This is a route to take if you are looking to make your way in the world, and are prepared to take considerable risks. Few of the English mercenary captains had noble or knightly backgrounds. John Hawkwood’s origins lay in an Essex village; he was the second son of a minor landholder. Some of the Gascons come from minor noble families, as is also the case with many of the Germans. Werner of Urslingen was exceptional in being of high-born ancestry, for he was a younger son of Duke Conrad VI von Urslingen, and claimed the title of Duke of Spoleto. When they are in Italy, some Germans claim titles that they are not really entitled to, and many of them are knighted on campaign there. So do not worry that if you fight as a mercenary you will be lowered in status. The contrary is far more likely to be the case.

John Hawkwood, the most successful of the English mercenaries to fight in Italy. He served the city of Florence well, and is remembered there with this magnificent fresco in the Duomo.

Opportunities

Italy presents the richest pickings for you in your career as a mercenary. The rivalries between the cities of the north lead to much fighting, and these cities are so wealthy that they can afford to hire the best soldiers from Germany, England and elsewhere. Peace does not present much of a problem; there is always another conflict and another city ready to recruit you. Florence is always opposed to Siena; Milan has numerous enemies.

The companies

To be a successful mercenary you need to be a part of, or preferably lead, a company. The first of these in the 14th century was the Catalan Grand Company of Roger of Flor, formed in 1302 from veterans of the Aragonese army that had been fighting in Sicily. The Company began by serving the Byzantine emperor, but soon started to operate independently, causing chaos in Greece, capturing Athens, and setting an example of destructive behaviour for others to follow.

The Germans

Next came the Germans. When the German emperor Henry VII died in Italy in 1313, his army was dissolved, and many of his knights remained in Italy to seek their fortunes. Ludwig IV’s journey to Rome in 1327 took more knights there, and as Ludwig could not pay their wages, many did not return to Germany with him. The first really large mercenary band in Italy, the Company of St George, was founded in 1339, with a leading role taken by Werner of Urslingen. It was defeated by a Milanese army on a snow-covered battlefield at Parabiago, near Milan, but Werner formed a new Great Company in 1342, which ravaged its way through northern Italy until the Germans returned home, much the richer. Werner returned again in 1347, remaining until 1351. He wore black armour, on which his motto was inscribed: ‘Enemy of God, Pity and Mercy’.

The Great Company Werner founded had various leaders after him, first Montreal d’Albano, who came from Provence and was known as Fra Moriale, and then the German Conrad of Landau. By the mid-14th century there were at least 3,500 German mercenaries in Italy. Many Germans go to Italy for a single campaigning season; to go for more than three or four campaigns is rare. There are exceptions:

•Haneken Bongard spent a quarter of a century in Italy.

•Conrad count of Aichelberg spent 15 years there.

Swabians and Rhinelanders normally look to Milan and Tuscany for employment; Bavarians and Franconians gravitate towards Venice.

The English and Gascons

The treaty of 1360 that resolved, for a time, the war between England and France left large numbers of soldiers unemployed. For some the solution to this problem lay in forming free companies, bands known as routiers. The leaders of the new companies were mostly English or Gascon. One of the largest, the Great Company, took Pont-Saint-Esprit in the Rhone valley in 1360, using it as a base for launching devastating raids. In 1362 a routier force defeated a French royal army at Brignais. One of the most notable bands at this time was the White Company. It sprang from the Great Company and was initially led by a German, Albert Sterz; he was replaced by Hugh Mortimer of La Zouche, a kinsman of the king of England. The White Company was well organized, with a command structure of 12 corporals. It was invited to Italy by the marquis of Montferrat, and in 1363 defeated Conrad of Landau’s troops.

This is a world of fluctuating allegiances; you will find that you are playing politics as the companies disintegrate and reform.

•Sterz and his compatriot Haneken Bongard left the White Company and formed the Company of the Star in 1364.

•In 1365 the men of the Star defeated and destroyed the White Company, many of whose former members joined John Hawkwood in the Company of St George.

•Under Hawkwood, many of the English knights in Italy came together in a new company in the early 1370s. This was said to be 10 miles long as it ravaged its way through the Italian countryside.

The companies can present a serious problem; if the mercenaries are not employed by a city, perhaps during a period of truce, they act independently, extorting money where they can, and bringing terror to the land. Nowadays, however, the number of foreign mercenaries in Italy has declined. The glory days of the companies were in the 14th century. Nevertheless, there are many opportunities for you. The great Italian cities will always need to hire experienced mercenaries.

The Italians

You do not have to be a foreigner such as Hawkwood to succeed as a mercenary in Italy, though it may help. Recently Italians, notably Alberigo da Barbiano, who died in 1409, have come to take much more of a leading role in the mercenary companies, although there are still plenty of opportunities for foreign knights. There are earlier examples of important Italian mercenaries:

•Guidoriccio da Fogliano came from a noble family in Reggio Emilia. He led Siena’s army from 1327 to 1334, served the Della Scala family in Verona, and joined forces for a time with Werner of Urslingen. He has been made famous for posterity by a fresco in Siena.

•Ambrogio Visconti was another notable Italian mercenary. He was the bastard son of Bernabò Visconti of Milan, and as such could not hope to receive a worthwhile inheritance. He sought his fortune in war, founded a new Company of St George in 1365, and fought alongside John Hawkwood.

The Italian mercenary Guidoriccio da Fogliano commanding Siena’s army in 1328, painted by Simone Martini. His horse is shown pacing, a movement in which the legs on one side move forward together, followed by those on the other side. (Palazzo Pubblico, Siena)

OF CONDOTTIERI

Italian cities usually insist that musters are held monthly, to make sure that troop numbers are correct.

•

The Florentines define victory as defeating a force of at least 200 horsemen.

•

John Hawkwood used loud music to alarm townspeople during a siege.

•

The names of mercenary bands in Italy include the companies of St George, the Hat, the Rose, and the Star.

•

In Italy, English soldiers are said to shout louder than any others.

•

It is said that the Italian word, bistecca, derives from John Hawkwood’s habit of ordering beef steak in English.

Organization

You should make sure that the company you join is well organized. A typical company should have the following:

•A captain-general.

•A chancellor, normally Italian, to look after the legal affairs, such as negotiating contracts and drawing up documents.

•A treasurer to look after the finances.

•Marshals and constables to command the banners, which will normally consist of 15–20 men.

•Guastatori, the devastators, who do the job of ravaging the countryside.

•Women to do the laundry, grind corn with hand-mills, cook and provide other services.

Tactics

The methods of the English mercenaries are the best to follow. They have introduced new fighting techniques to Italy. The basic fighting unit employed by the Germans was the barbuta, composed of two men, a knight and a page (the latter in support). The English introduced the formation known as the lance to Italy; this has three men – knight, squire and page – and became the standard component by the end of the 14th century. The men of the celebrated English White Company fought on foot, two men holding a single lance, advancing carefully in small steps. Archers provided support to this solid formation. As important as these techniques is the ability to march long distances, often at night. The English troops would appear, apparently from nowhere, to launch surprise attacks on towns and castles using ingenious scaling ladders. Under Hawkwood’s command their operations were well planned and properly co-ordinated, as well as being based on sound intelligence; his is the model to follow.

The battle of Castagnaro in 1387 provides a good demonstration of how to fight. Hawkwood was serving the city of Padua, when his small army was pursued by a much larger army from Verona. He established a strong position, protected by ditches and marshes. He also took care to fill a ditch at a vital point, providing a route around the Veronese position. Most of his men-at-arms dismounted, and were drawn up in three lines; his archers were in support, and he kept a cavalry reserve. He countered a frontal attack by the Veronese by outflanking them, and attacked their rear with his mounted knights and men-at-arms. The similarity to the tactics used by the English in France is obvious, with parallels in particular to the battle of Poitiers.

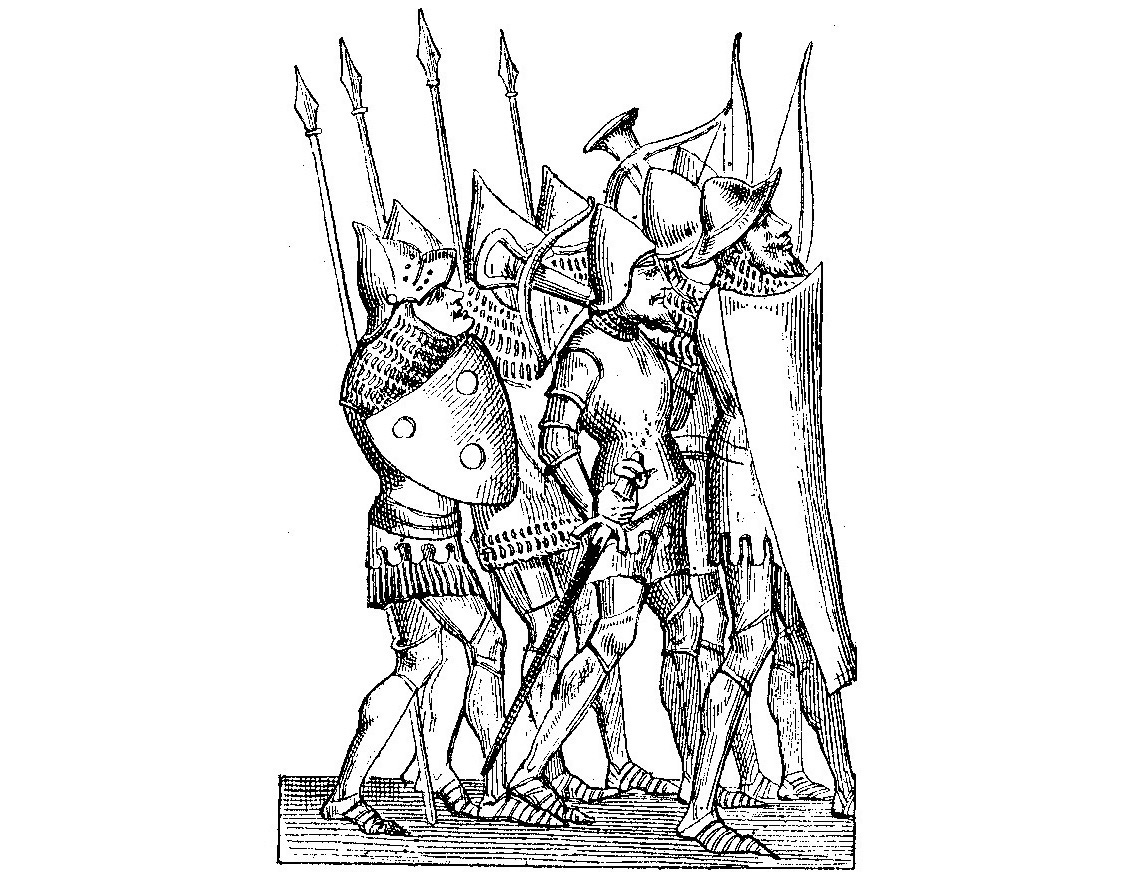

A group of dismounted men-at-arms, ready for battle. (From A. Parmentier, Album Historique, Paris 1895)

Language difficulties

You need to have some language skills if you are to succeed as a mercenary; it will not be enough to let your sword speak for you. Albert Sterz, originally from Germany, was fluent in English. Conrad of Landau, on the other hand, had problems. He was defeated in 1363, in part because he could not communicate properly with the Hungarians in his company. ‘Alt, alt’, he shouted at them, but they would not halt. Provided that you have some knowledge of French, you should be able to pick up Italian, something that the Germans find very hard. Ideally, you should know Latin, but John Hawkwood did not, and managed very well by using clerks and notaries.

Negotiations

A successful mercenary needs many skills; it is not enough just to be good at fighting. You will have to negotiate with your employers, and Italians are the best businessmen in the world, so it won’t be easy. It is probably fairly easy to agree on the rate of pay, but it is when it comes to the extras that it gets interesting. A good strategy is to insist that you are paid for non-existent soldiers – known as ‘dead lances’. As much as 10 per cent of your troop can consist of these ghostly warriors. It is probably a good idea to settle for a lump sum as compensation for lost horses; that way you will not have to prove that the horses really have been killed. In addition to these charges, you can usually extort bribes from cities anxious for your services. You need to watch your employer though; the Italians have a nasty habit of imposing taxes on your pay, and income after tax is rarely as much as you thought it was going to be.

Chivalry

It may seem that few of the knightly virtues are apparent in the attitude of the mercenaries. The German Conrad of Landau put it clearly:

It is our custom to rob, sack and kill he who resists. Our income is derived from the funds of the provinces we invade: he who values his life pays for peace and quiet from us a very steep price.

There is, however, much that is contradictory in the chivalric code, meaning that, conveniently, it can be used to justify the apparently unacceptable, such as:

•The ravaging of the countryside.

•The levying of protection money.

•The seizure of food supplies and the driving off of animals.

•The slaughter that follows the successful storming of a town.

These are common elements in warfare today, and are warranted by the laws of war. They do not necessarily stand in opposition to the ideas of chivalry, ideas which have a useful flexibility to them. The actions of a mercenary such as Hawkwood are not necessarily any less chivalrous than those of the Black Prince. The latter’s troops were responsible for massacring the inhabitants of Limoges in 1370; Hawkwood’s men were among those who took part in the killing at Cesena in 1377. It was, however, Cardinal Robert of Geneva, not Hawkwood, who demanded ‘blood and justice’ at Cesena. The horrific events there did not dent Hawkwood’s chivalric reputation.

If you display valour in fighting, show due loyalty by adhering to the terms of the contracts you make with your employers, and display generosity to your followers, you will be fulfilling your obligations as a knight. It is important that you should conduct yourself in accordance with the accepted laws of war; if you go against these conventions, you will find yourself deprived of such protection as those conventions offer. Hawkwood may not have done all that is expected of a chivalrous knight; he never, for example, went on crusade, and he fathered illegitimate children. He was, however, brave, loyal, and a superb soldier, and as a result has a fine reputation as a chivalric hero.