When we are in taverns, drinking strong wine, and the ladies are near, looking at us, drawing their kerchiefs round their smooth necks, their grey eyes smiling, resplendent with beauty, nature provokes us in our hearts to fight.

THE VOWS OF THE HERON, MID-14TH CENTURY

• • •

Chivalric culture makes much of women. They should be an inspiration for knights. They will be there to cheer you on in tournaments and jousts. Their encouragement will help to persuade you to go off to fight. Should you have doubts about why you are fighting, just think of your lady-love, and try to fulfil her dreams for you. Read Geoffroi de Charny, and he will tell you that you should love, protect and honour all women who inspire knights and men-at-arms to undertake worthy deeds. In reality it is, however, all rather more complicated than that.

Good or evil?

If you listen to some priests, you will gather that women are wicked creatures, who are just after one thing. The early Christian fathers provide good ammunition for such opinions, describing woman as ‘a temple built over a sewer’. According to this tradition women are imperfect beings as compared to men. Current medical opinion backs this up:

•Women have a different balance of the humours from men. They are colder and have more phlegm, and as a result are fickle and unreliable.

•Women are more sexually voracious than men.

•Female anatomy is strange, for women have a womb that wanders about the body. This can cause them considerable problems.

•Women have testicles, but in contrast to men’s, these are small, and hidden internally.

However, the cult of the Virgin Mary leads to very different conclusions about women, as do the ideas about courtly love that have been developing since the 12th century. Love in this tradition is a pure emotion; sex does not come into it.

•Women are to be adored, protected and honoured.

•Women are merciful; they intercede to seek pardons.

•They are pious and virtuous.

You will find a range of ideas about women in the stories that you read and hear, but you will normally find them depicted in ideal terms. The perfect woman has a white skin, golden hair, an elegant nose, a mouth well made for kissing, and a perfect figure. Even her toes will be just right.

A love poem about the fair maid of Ribblesdale provides a description of such a maiden:

Her eyes are large and grey, and she,

When darting lovely looks at me,

Arches her brows with light.

The moon that stands in heaven’s height

Sheds not such radiance at night.

The poem is, however, an elaborate joke, for it goes on to say that the maid also has an extraordinarily long neck, like a swan, over 9 inches long, and arms an ell in length, almost 4 feet. The message is clear; you should not take all these descriptions too seriously.

Respect and protect

Chivalric doctrine is clear about the fact that you must respect women. De Charny explains how important it is that you protect your lady-love’s honour. You should not boast of your love for her, or behave in such a way that it becomes public knowledge; otherwise you may embarrass her, causing trouble. When Boucicaut was at court, he was gracious, courteous and entirely proper in his demeanour; no one could even tell from his behaviour which lady was the one he loved. If you must kiss women, note the example of Henry of Grosmont, the duke of Lancaster. He found that beautiful ladies of rank disapproved of this, and so he gallantly directed his behaviour towards those of lower classes.

As a good knight, you should protect women from harm. Your concern will primarily be with women of your own social class; when Boucicaut created his order of the White Lady on a Green Shield, he was concerned only with ladies of noble lineage. You may well not worry too much about what happens to peasant women in war, but you should look after aristocratic ladies. There are examples to follow:

•John Hawkwood is said to have saved 1,000 women from a dreadful fate at the horrific massacre at Cesena in 1377.

•In 1358 the rebellious French peasants in the rising known as the Jacquerie were threatening a number of noblewomen who had taken refuge in the town of Meaux. The count of Foix and Jean de Grailly (known as the Captal de Buch) drove the peasants off and slaughtered them.

•At the taking of Caen in 1346, Thomas Holland and his companions are said to have saved many women and maidens from a dreadful fate; but unfortunately they were unable to do the same for the nuns of the abbey of the Trinity.

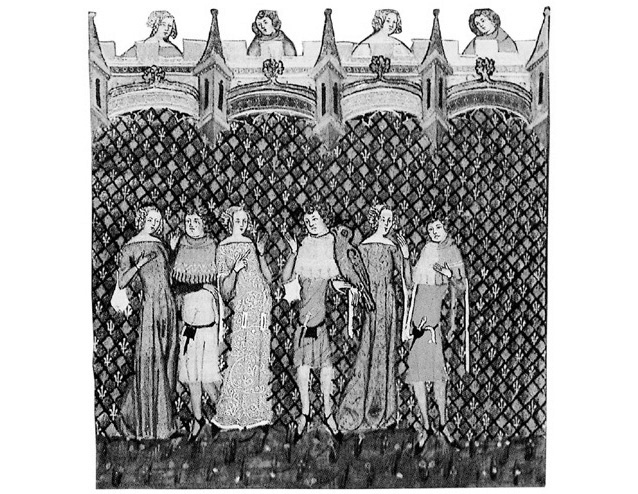

A group of knights and ladies in fashionable dress. The ladies wear long flowing gowns with a wide neckline. (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

It may seem obvious to you that women should be treated properly, but this has not always been the case. When Edward I captured Robert Bruce’s sister and the countess of Buchan in 1306 the two women were not sent off to nunneries in England as might have been expected. Instead, cages were constructed for them, and they were placed in full public view, one at Roxburgh, and one at Berwick. The fact that the cages were fitted with en-suite facilities hardly excuses Edward’s action, but curiously no one accused him of being unchivalrous. There is a tale doing the rounds about Edward III, king of England, who is said to have raped the countess of Salisbury. This, however, you should not believe; the names, dates and places simply do not add up. Edward was a chivalrous man.

Vows and tokens of affection

It is often their wives and girlfriends who persuade knights to make vows to perform valiant deeds in war. You may find that your loved one gives you a token, such as a detachable sleeve, for you to tie to your helmet or your lance; in return you will be expected to perform noble deeds in her name. William Marmion’s ladylove chose to give him a gilded crest for his helmet, and instructed him to make it famous in the most dangerous place in Britain. Marmion duly set off in an act of devotion, and was almost killed for his pains at the siege of Norham Castle.

Ladies sometimes use questionable methods of persuasion. When the Scots captured Douglas Castle early in the 14th century, they found a letter on the body of the constable, in which his girlfriend promised to surrender herself to him once he had managed to keep the castle secure for a year. If you are offered a bargain along such lines, ask yourself whether the lady really means it. She may just be looking for a way to get rid of an unwanted suitor, by sending you off into danger.

A Burgundian ceremonial shield, depicting a knight making a vow to his lady. The motto in a scroll reads ‘You or death’. A skeleton behind the knight suggests that death will be the outcome. (British Museum, London)

At the start of Edward III’s war with France, a great banquet was held, at which the centrepiece was a roast heron. According to a poem about the event, The Vows of the Heron, all present took vows to perform notable actions in the fighting that was to come. The beautiful daughter of the earl of Derby placed a finger over one of the earl of Salisbury’s eyes, and he swore not to open it again until he had set fire to the French countryside and fought against Philip VI’s army. The poem makes fun of the practice. Salisbury had already lost the sight in one eye, and was either agreeing to go to war blind, or making a meaningless vow. Although this is a satirical account, it is the case that a number of young men went to war in the late 1330s wearing eyepatches in fulfilment of promises they made. This was not sensible, and the girlfriends who persuaded them to do this should have known better.

You do not need to make impractical or dangerous vows, and you should ditch the object of your affection if she tries to get you to do so. You can find more sensible women. Elizabeth de Juliers, niece of the English queen Philippa and wealthy widow of the earl of Kent, fell in love with Eustace d’Auberchicourt. She took a wise view of what a knight needs, and provided practical help as well as symbols of devotion. While he was fighting in Champagne, ‘she sent him several hackneys and chargers, with love-letters and other tokens of great affection, by which the knight was inspired to still greater feats of bravery and accomplished such deeds that everyone talked of him.’

Tournaments

Women have a big part to play in all the events that surround tournaments, and you will have an enjoyable time playing court to them, flirting in, no doubt, the most proper way. The ladies lead the knights in processions, they fill the spectator stands, cheer their favourite champion, and enjoy the dinners and the dances. At the London event of 1390, there were even prizes for them, as the general invitation to the jousts explained:

And the lady or damsel who dances best or leads the most joyful life those three days aforesaid, that is to say Sunday, Monday and Tuesday, will be given a golden brooch by the knights. And the lady who dances and revels best after her, which is to say the second prize for those three days, will be given a ring of gold with a diamond.

The example of a German 13th-century tournament in Magdeburg, in which a woman was offered as the prize, is not one that should be followed. Beware, too, lest the excitements of the tournament lead women to go too far. There is a story of a group of eye-catching young ladies in England, some 40 or 50 in number, who took to dressing as men, and appearing on fine horses at tournaments. They also, to the disapproval of the chronicler Henry Knighton, but no doubt to the delight of the onlookers, ‘wantonly and licentiously displayed their bodies in a scurrilous manner’.

Marriage: a tale of two Constances

In planning your career, you should think hard about what sort of marriage you should enter into. The right wife will provide you with the support that you need in your military career. Marry wealth, and you will have the resources you need to meet all the costs involved in war. Marry unwisely, and you will face problems and distractions that you could do without.

Hugh Calveley provides a cautionary note. In 1368 he married Constança, daughter of a Sicilian noble and one of the queen of Aragon’s ladies. She brought a substantial dowry with her, but if she was initially pleased at the prospect of marriage to a hero of the Anglo-French war, her pleasure soon palled. The marriage was childless, and Constança refused to leave her estates in Valencia to join Calveley, becoming instead the mistress of Pedro IV’s son Juan.

In contrast, Calveley’s companion-in-arms Robert Knollys had a highly successful marriage. He did not seek a bride with a fortune, or an exotic foreign beauty. His Constance hailed from Yorkshire, and was a woman of character rather than wealth. She met Robert in Brittany, where she had been taking an active part in the war, even leading contingents of troops. She frequently accompanied her husband on his expeditions, taking their children with her. It is, one need hardly add, highly unusual for a woman to take part in war in this way.

The best advice is to pursue one of the following courses of action:

•Find a wife like Constance Knollys, who will share your experiences to the full.

•Follow the example of Eustace d’Auberchicourt, and find a wealthy widow who loves you.

•Marry someone capable of running your affairs; John Hawkwood’s Italian wife Donnina was highly literate and was a good businesswoman.

You ought to pay more attention to your lover than to your falcon. The German knight Konrad of Altstetten’s lady-love is shown in the early 14th century Codex Manesse trying to distract his attention while he feeds his bird. (From Codex Manesse, Zurich, c. 1310–40. University Library, Heidelberg)

OF LADIES

In 1338 Agnes, Countess of Dunbar, successfully defended her castle for 19 weeks.

•

The French doctor Henri de Mondeville suggests that if well-endowed young women are reluctant to undergo cosmetic surgery, they can wear shirts fitted with two appropriately shaped bags so as to provide support.

•

The English knight Thomas Murdak was murdered by his wife in 1316; she and her associates chopped him in half.

•

Some of Richard II of England’s knights were accused of paying too much attention to women, ‘showing more prowess in the bedroom than on the field of battle, defending themselves more with their tongue than with their lance.’

•

In 1386 the Paduan army captured 211 prostitutes when they defeated an army from Verona. They were treated very honourably, and dined with the lord of Padua.

Trouble

It may be the case, as de Charny and others would argue, that devotion to a lady inspires you to do great things on campaign and on the battlefield. However, you should sometimes take a reality check on these romantic ideals; women may cause you problems. Take the case of William Gold, who served in Italy alongside John Hawkwood. Gold acquired a French mistress, called Janet, who failed to tell him that she already had a husband. She ran off, taking some of his money. William was heartbroken, and wrote about it in dramatic terms:

Love overcometh all things, since it prostrates even the stout, making them impatient, taking all heart from them, even casting down into the depths the summit of tall towers, suggesting strife, so that it drags them into deadly duel, as has happened to and befallen me for the sake of this Janet, my heart yearning so towards her.

All the efforts he made to get Janet back distracted Gold from the business of war, rather than inspiring him to perform great deeds of valour. Eventually he forgot Janet, and without womanly distractions served the city of Venice so well that he was made a citizen.

You will find nothing in the pages of Geoffroi de Charny’s work to suggest that your lady-love will be anything other than loyal and devoted. Do not believe all that you read. You may well be worried about what she is doing in your absence, and you could be right to be concerned. In 1303 William Latimer, one of Edward I’s household knights, went to the king when they were campaigning in Scotland to complain that he had heard that his wife had been abducted, and that she had gone willingly. The king was furious, and demanded that some legal remedy be worked out. Latimer was eventually given full powers to arrest his wife and get her back, but by then she was safely ensconced as the mistress of another knight, Nicholas Meinill, and though in time she would leave him too, she never returned to Latimer.

The chronicler Froissart was told a story about two brothers-in-arms, Louis Raimbaut and Limousin. Raimbaut had a mistress of whom he was inordinately fond, and when he was away campaigning, he entrusted her to Limousin. However, he did rather more than look after her, and the gossip duly reached Raimbaut, who had Limousin stripped near naked, marched through the town and publicly beaten. Raimbaut was later captured, to be taunted by Limousin: ‘One woman might have served two brothers-in-arms, such as we were then.’ That is not a good idea for you to follow up.

Boucicaut never allowed his eyes to stray, but it may be too much to hope that you will be able to follow his example of chivalric morality. What should you do with the outcome of illicit liaisons? Walter Mauny had two illegitimate daughters, Maloisel and Malplesant, and packed them off to a nunnery. When John de Warenne, earl of Surrey, discarded his mistress, he sent his two sons by her away to become knights of the Hospital. In contrast, John Hawkwood looked after his illegitimate children. His son Thomas became a soldier, and distinguished himself in the Anglo-French war, while Hawkwood used his influence with the Papacy to secure a career in the church for another son, John. This is surely the example to follow.