Introduction

Books about war were written to be read by God A’mighty, because no one but God ever saw it that way. A book about war, to be read by men, ought to tell what each of the twelve of us saw in our own little corner. Then it would be the way it was — not to God but to us.

In The Soldiers’ Tale, Samuel Hynes characterizes the war narrative as “something like travel writing, something like autobiography, something like history,” yet something not quite belonging to any of those genres. Hynes concludes that “war is more than actions; it is a culture.”1 Military units have their own culture, too, and we would argue that military ranks have a kind of culture as well. This book is about five army lieutenants of the 1st Battalion, 64th Armor Regiment, 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized) during Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm — five young men just out of school and leading soldiers for the first time. It is about leadership at the platoon level, about the men and women we led as well as the officers who commanded us. It is about the family and friends we left behind.

The Iraqi army invaded Kuwait on 2 August 1990. A light infantry brigade from the 82d Airborne Division deployed within days to establish and secure the airfield at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, and to signal the United States’s commitment to the region. The 82d Airborne, the 101st Air Assault, and our 24th Infantry belonged to the Eighteenth Airborne Corps, the army unit designated to deploy rapidly abroad. Elements of the Eighteenth had carried out the 1980s’ operations in Grenada and Panama. As the corps’s heavy component, however, the 24th had not participated in those missions. With its 1,600 armored vehicles, 3,500 wheeled vehicles, and 90 helicopters, the division depended on ships, rather than airplanes, to deliver its equipment to distant battlefields. But unlike the opposition in Grenada and Panama, the Iraqis had the fourth-largest army in the world, with an estimated tank fleet of over five thousand. The defense of Saudi Arabia required a sizeable armored ground force, and the 24th Infantry was the first armored division — the first full division of any kind — to arrive in country. The original mission, the defense of Saudi Arabia, was dubbed Operation Desert Shield.

Based at Fort Stewart, Georgia, the 24th loaded its vehicles and equipment on ships at the Savannah port and flew the bulk of its personnel to Saudi Arabia on civilian aircraft. Ship transit time from Savannah to Saudi Arabia ranged from fifteen to twenty-five days, so air transport was timed to get units in country a day or two ahead of their vehicles. Hussein’s decision not to push into Saudi Arabia gave the soldiers of the Eighteenth Airborne Corps six months to acclimate themselves to the desert, establish a logistics system, and plan and train for combat as the rest of the coalition forces poured into the theater.

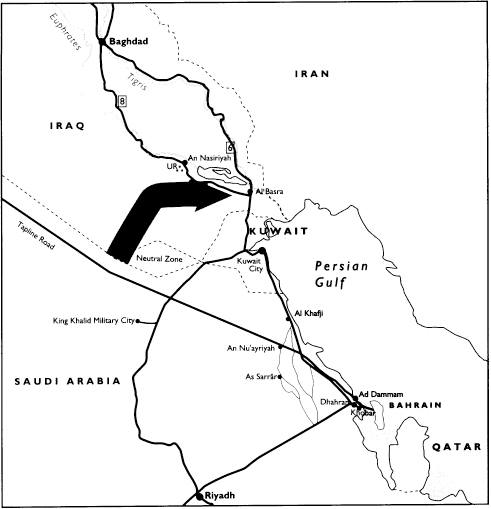

Operation Desert Storm commenced with an intensive air phase on 17 January 1991, two days after the United Nations’ deadline for Iraqi withdrawal had passed. During the air campaign, the Eighteenth Airborne moved to an attack position over three hundred miles to the west. We traveled along Tapline Road, a single two-lane paved road paralleling the Saudi-Iraq border and stretching across the Arabian peninsula. The move, which had to be conducted across the Iraqis’ front without their knowledge, was successful thanks to corps planners, the incompetence of Iraqi military intelligence, and most especially the coalition’s total air supremacy. When the ground phase of Desert Storm began on 24 February 1991, we found ourselves deep in the desert along the border, on the west side of the diamond-shaped neutral zone between the two countries.

The attack launched into a sandstorm that blinded both the enemy and us. While the marines and Arab forces hit Kuwait from the south, and the American Seventh Corps broke around the end of Hussein’s line and into Kuwait from the west, the Eighteenth Airborne swept through Iraq well to the west, then drove east through the Euphrates River Valley to complete the encircling of Iraqi forces in Kuwait. All in one hundred hours. The coalition military force’s commander in chief, Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, referred to the corps’s attack as a “Hail Mary” play and considers the commander of the 24th Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Barry McCaffrey — a Vietnam veteran with two Distinguished Service Crosses, two Silver Stars, and three Purple Hearts — his “most aggressive and successful ground commander of the war.”2 Joe Galloway, one of America’s best war correspondents, describes our division’s portion of the attack thusly: “In four days, the 16,530-man 24th Mech had conducted what one American officer called ‘the greatest cavalry charge in history.’ It had charged all the way around Hussein’s Army, almost 250 miles from the barren Saudi Arabian border to the gates of Basra — farther and with more firepower than General George S. Patton’s entire 3rd Army had hauled across France.” By war’s end, the division had disabled two infantry divisions, four Republican Guard divisions, and the 26th Commando Brigade. It had destroyed 363 armored vehicles and captured over five thousand prisoners.3

Casualties suffered by the 24th during the war were amazingly light, eight killed and thirty-six wounded. The number killed in this last campaign before the division’s deactivation coincidentally matches the number killed in its first battle, shortly after activation, when its soldiers scrambled out of their barracks to defend Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and brought down five Japanese aircraft. “First to fight” — in World War II, and then again in Korea — the phrase is the division’s motto. (Again answering the division’s Pearl Harbor ghosts, the 24th in Desert Storm destroyed twenty-five high-performance fighter aircraft and helicopters.) The Desert Storm casualty rate speaks volumes for American tactics, equipment, training, and leadership. But we executed neither Desert Shield nor Desert Storm flawlessly. Another eight division soldiers died during Desert Shield,4 and this book touches on a number of problems encountered while preparing for and fighting in combat, including the distressing issue of casualties from friendly fire. “This thing was risky as hell,” Major General McCaffrey reminded an army historian the day of the cease-fire, “and we’re going to forget that very quickly.”5 America’s postwar knowledge of the operation’s speed and relative bloodlessness should not be allowed to erase the memory of the risks and fears we faced.

The 24th Infantry Division’s “Hail Mary” Attack, 24–28 February 1991

■Writing a book with five narrators poses its own challenges, and we have done our best to create a cohesive narrative. Limiting the authors to lieutenants from the same armor battalion helps unify the book, but confusions and conflicts among our voices and with other accounts and records were bound to emerge, and difficult to avoid. In his history of the Irish Guards, Rudyard Kipling writes that

a battalion’s field is bounded by its own vision. Even within these limits, there is large room for error. Witnesses to phases of fights die and are dispersed; the ground over which they fought is battered out of recognition in a few hours; survivors confuse dates, places and personalities, and in the trenches, the monotony of the waiting days and the repetitious work of repairs breeds false mistakes and false judgments. Men grow doubtful or oversure, and, in all good faith, give directly opposed versions…. The shock of an exploded dump, shaking down a firmament upon the landscape, dislocates memory through half a battalion…. When to this are added the personal prejudices and misunderstandings of men under heavy strain, carrying clouded memories of orders half given or half heard, amid scenes that pass like nightmares, the only wonder to the compiler of these records has been that any sure fact whatever should be retrieved out of the whirlpools of war.6

For us, the speed of our offensive blurred our memory, though our accounts do not diverge as drastically as those collected by Kipling. Doubtless, other members of the 24th during Desert Shield and Desert Storm have still different perspectives and remembrances. Inconsistencies become an accuracy of sorts.

Four of us received our commissions from the U.S. Military Academy; the fifth came from ROTC out of the University of Nebraska-Kearney. We four from West Point had been commissioned in the army slightly over a year and had been with the 24th Infantry a matter of months. We were still learning our jobs, getting to know our soldiers, and trying to become proficient in our profession. Two of us were married. We were all in our early twenties.

| Neal Creighton Jr., Chicago, Ill. | Alex Vernon, Chapel Hill, N.C. |