3

Desert Storm: The Air War

17 January through 23 February 1991

Iraq will take a terrible pounding during the air campaign. Will absorb more bombs in the first 24 hours of the war than was dropped on North Vietnam.

17 January-21 February 1991

According to the Eighteenth Airborne Corps chronology, OPLAN Desert Storm was put into effect at 0152 hours on 17 January with the launching of one hundred Tomahawk cruise missiles from U.S. Navy ships in the Gulf.

Hundreds of miles away, in Task Force 3–15’s temporary staging position, I was curled asleep in my customary position on the blow-out panels behind my hatch. Months before I had figured out how to sleep on the three rectangular panels by wedging my hipbone in the crevice between the center panel and one of the others, and my shoulder and outstretched arm in the other crevice. At 0300 Sergeant Dock was on guard, and he had turned on his contraband radio when he saw an unusual amount of traffic in the sky. He woke me and set the radio by my head. “Sir, it’s started. Listen to this.”

I heard Marlin Fitzwater, the White House spokesman, make the announcement. “The liberation of Kuwait has begun.” This may have been the first time I learned the operation’s name: Desert Storm. Before hitting the sack the previous evening I had received the latest installment of articles from the journal Parabola, sent to me by my oldest brother, Walt. The theme of the issue from which these articles came was “Liberation.”

Neal calls Orion the Warrior “God’s eternal monument to soldiers.” The poet and mythologist Robert Graves — also a veteran of the war to end all wars — calls him the Hunter. But to me he is the Liberator: For a beautiful woman’s hand, Orion liberated her father’s island kingdom of the monstrous creatures that had overrun it. Orion then boasted he would liberate the world of all its monstrous creatures, and his constellation preserves his fatal combat with one of those, a giant, carapace-armored desert scorpion.

I lay awake watching the sky. Watching the blinking lights of warplanes.

S.Sgt. Lester Deem woke Greg Downey at 0400. “Sir, I think the shit’s about to hit the fan.” Greg looked up: “The dark sky was filled with an armada of blinking lights, and the desert night was roaring. The reality of combat is both frightening and exhilarating. I sat in awe watching the coalition air power operate above. I could not take my eyes off the dozens of fighter aircraft flying over us, circling in the air behind the larger KC-135 refueling planes, topping off their fuel tanks for another run. I felt I was in a dream, knowing that history was unfolding before my eyes and that everyone around me would be playing a part.”

Rob Holmes too was asleep on his usual turret-top position. He had gone to bed at midnight, knowing “that something had to happen soon. My men were beat up from the conditions and worn out from the stress of our six-month sentence in Saudi. We were ready to go home regardless of what we had to do to get there. Tensions ran high.” His company commander’s gunner, Sgt. Tom Wanna-maker, climbed aboard the tank, woke him, and whispered, “Sir, I’ve got a message from the commander. Desert Storm has been executed.” Wannamaker paused. “Do you know what that means?”

Rob pulled out a beat-up old radio he had gotten in a trade to an Arab for a case of chem lights: “Hell, yes, I knew what that meant. The BBC commentators were chattering away, detailing the Americans’ start of the air war. Desert Shield was over. Desert Storm had begun. I lay back down and listened to the BBC as I watched the planes overhead. Every so often the horizon would light up, and thunder would roll across the desert a few seconds later. We were really bombing Iraq. At some point it would be the army’s turn. I didn’t sleep the rest of the night, but I was relaxed and calm as I watched the planes fly above, about like I had spent countless nights in the desert watching shooting stars. Even doing the play-by-play for a war, the unflappable British accent on the radio I found rather soothing.

“Most of my soldiers were awake, watching and listening. We had all heard exploding ammunition before. This sounded different. A gunnery range is a hodgepodge of distractions, frustrations, of hurry up and wait, the rounds firing fitfully. But this was almost like a concert, a symphony, its rhythm pulsing across the desert.

“I knew we would be going home soon, but our path would be through Iraq. No one bothered me the rest of the night. I just lay there listening to the rumble and watching the flashes on the horizon. It was an awesome night.”

Neal Creighton was sleeping on the back deck of Wild Thing when Spc. Gullet woke him. “Sir, the commander wants to see you.”

“All right,” Neal replied. He crawled out of his sleeping bag, pulled on his desert parka, and groggily dismounted the tank. As he approached Captain Schwartz at his Humvee, he could hear the AM radio.

“Neal, we are bombing Iraq. I just wanted to let you know it has started.”

But Neal didn’t need to be told: “I knew. We were quiet for awhile. Eventually I found something to say. ‘I guess we weren’t kidding about the UN’s deadline.’ I went back to my tank and as the sun rose, I could see planes heading north.

“That morning, I told the platoon we were at war. We listened for the early damage reports on the Voice of America and the BBC. The news was good. As we were listening, one of my sergeants asked me the same old question: ‘When do you think we are going to get home, LT?’

“‘You know how I usually answer that question, Sergeant Davis — I don’t have a clue. I’ll tell you what. I’ll take a wild-ass guess and say we will stomp the Iraqis and be home by March twentieth.’

“The sergeant pulled out his calendar and wrote a cluster of stars in the box for the twentieth of March. ‘See these stars, LT? These are the stars you are going to see if we don’t get home by March twentieth. If we do get home by then, I owe you a case of beer.’

“‘It’s a deal.’ I laughed. Then I turned from him to search for pen and paper. The reality had finally hit me. We were going to war, and my platoon was in the front. If the enemy was as good as we were, my chance of survival was not high. I began to write a letter to my daughter:

Dear Katherine,

When you get this letter, you will be learning how to walk and it will be years before you understand what I have written. I am writing at a moment when our country is at war. Right now your father feels tired, but my morale remains high.

I do not know if I will survive this conflict. I want you to know in my own words who I am and how much I will always love you. During my short life, I have had both setbacks and victories, but I always tried to do my very best. I was born into a military family. My father was a career officer, but despite his busy life, he always made time for his children. I think I was my mother’s favorite just like you will always be mine.

During my school years, I lived all over the world and made many friends and saw many places. I was a good athlete and participated in football, wrestling, and tennis throughout high school. After high school, I enlisted in the army and later received an appointment to West Point. I went through Airborne, Ranger, and SERE courses. Ranger School caused a lot of strife in my life, but I’m proud to say that I wear the Ranger Tab.

Right now, I am the lead platoon leader for a 750-soldier task force. We may soon fight, and your father will be in front. Everyone knows fear, and I am afraid that I may not come back. I know my platoon will do well, and I hope very much to return home soon.

Take care of your pretty mother. She has made a lot of sacrifices for our family and she loves you very much. You are the joy in my heart. I will always love you.

Dad

Reading Neal’s letter, I can’t help but recall that early fall day in 1989 at Fort Knox when I learned of Mary’s pregnancy, when I learned how truly surprising it was to them, because they had been told they could not have children.

■With the sunrise on the seventeenth came a SCUD missile warning. Gas masks were donned, then doffed some twenty minutes later. Otherwise, a surprising mood of jubilation carried the soldiers. People smiled and joked at breakfast. From the relief I supposed. It was finally happening. From the relief, and the knowledge that the beginning of the war took us one step closer to home. I had felt it twice before: first when we arrived at Hunter Army Airfield to wait on our flight, finally putting to rest the initial tension and questions of the deployment, and played Frisbee and paddleball; then when we landed in Saudi Arabia, stepping out of the plane past the crying stewardesses.

For Greg Downey, “it all seemed so sterile at first. Our air power ruled the skies, and we were not being subjected to the same bombardment that the Iraqi army was receiving. Our mood was high. Everyone wanted to get into the fight. The harsh reality of combat did not hit me until I saw one of the first casualties of the air war. One of the coalition planes screamed one hundred feet overhead, the pilot doing his best to nurse a severely damaged fighter jet back to an airfield farther south. I wondered if he’d make it back. I still do.”

On the eighteenth, the hair clippers sang and danced again. Some of my guys shaved their heads except for a one-inch Mohawk strip. They ran about laughing and taking pictures. It reminded me of the surfer hitting the waves after a battle in Apocalypse Now. The clowning ended, and the Mohawks came off.

Sfc. Freight continued to be a problem for me. I asked Swisher to ask Lieutenant Colonel Gordon if I could gain an audience with him to plead my case. I asked Captain Baillergeon to ask the same of Lieutenant Colonel Barrett. And I told Greg Jackson that I was about to fire my platoon sergeant myself, without endorsement from my chain of command. Order him off his tank and out of the platoon, order him to report to the first sergeant, order him publicly and loudly so the entire company sitting in our tight line would hear. Order Rivera to become the platoon sergeant again. Dare Swisher to countermand me, or fire me, publicly and loudly, so the entire company sitting in our tight line would hear. Greg again attempted to dissuade me. He implied that I could get myself in serious trouble — neither of us thought Swisher would court-martial me, but he could have, and in either case I was jeopardizing my career. And how would it stand the platoon if I were fired and did not lead them into battle?

Once again I did not have the audacity, the whatever, to act my conscience. I wonder how intent I was, how much of my plan was less plan than outburst of frustration and indignation.

The big event on the twenty-second was Lieutenant Colonel Barrett’s briefing of the concept of the ground war plan. I had already learned something about it the first week of January; my letters first refer to it anyway on the fourth: “Greg [Jackson] and I avoided Swisher today together for a half hour and talked about things, our situation and our feelings. We have a good idea of our role (as a division) in an offensive. We have no idea when. Greg mentioned something about Baker and Aziz meeting in Geneva.” This was right after we had drawn the new tanks, just before the task force obstacle breach when I would dream about Maria being pregnant, and see the sheep giving birth and the breast-feeding Badawiyah. Swisher must have sketched the plan for his lieutenants, though I don’t believe he had been allowed to know at that point either. Flash Gordon has since informed me that he and his fellow battalion and task force commanders “were not allowed to brief the plan until near execution date. I did not agree, but that was the guidance. I did brief the company commanders early because we needed their planning input.” I presume either Barrett had similarly briefed Swisher and his other company commanders, or Swisher learned from Gordon.

For Barrett’s official unveiling of the plan on the twenty-second, all of Task Force 3–15’s officers and first sergeants crowded into a GP Small tent. Armed guards outside the tent checked our IDs while Captain Swisher verified our identity for them. The guards collected our personal weapons; the infantry lieutenants carrying M-16s had to stack arms, leaning their rifles against one another in teepee clusters, so that the several stacks outside the GP Small looked like a diorama of a Native American campground. We were prohibited from writing home about the plan and ordered not to reveal it to our soldiers, so as to prevent the possibility of an intelligence leak. We were also not allowed to take notes during the briefing.

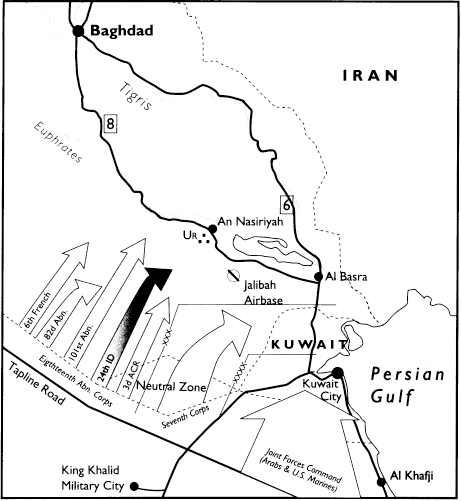

Our Eighteenth Airborne Corps would over the upcoming weeks make an enormous tactical displacement nearly five hundred kilometers northwest to attack positions along the Saudi Arabia-Iraq border. From those positions, we would launch our attack deep into Iraq and around Kuwait. The French Sixth Light Armored Division would be on the corps’s left flank; the U.S. 3d ACR would be on the right. Our mission was to sever the routes and communication lines into and out of Kuwait, encircling, enveloping, and trapping Hussein’s occupying army between us and Seventh Corps. The U.S. Seventh Corps (still arriving in Saudi Arabia from Germany),1 the marines, and all coalition forces except the French would attack into Kuwait. As Greg describes the plan, “Seventh Corps would be the hammer and we would be the anvil.” If I remember correctly, at the time of this initial concept briefing, the plan called for the 24th to spearhead the attack hours, perhaps an entire day, before all other units. This running start would ensure we had time to cover the distance and be in position north of Kuwait to block retreating or reinforcing Iraqi forces. If noticed by Iraq, our movement might also startle them enough to the advantage of the allied forces attacking into the heavily fortified and expectant Iraqi positions in Kuwait. Any Iraqi attention shifted our way, any adjustment or movement to deal with us, could only upset its main Kuwait defensive plans. And it appears that my memory is not far off the mark: The division’s Desert Storm Operations Plan of 15 January indicates that the 24th was to attack with the rest of the Eighteenth Airborne Corps on G-Day, H-Hour, about twenty-four hours prior to the Seventh Corps’s main attack.”

We would fight during the day. This afforded enormous advantages. Imagine the impossibility, in the case that we received artillery with or without chemical agents, of maneuvering at night buttoned-up, peering into the darkness through the periscoping vision blocks that surrounded the tank commander’s cupola, each vision block all of about one inch tall and four inches wide. I don’t think our night vision goggles would have done much good through the vision blocks. Those difficulties aside, Iraq most likely expected us to hit them at night. From whenever our senior leadership had made the decision, the media coverage of our night-fighting capabilities did not abate. A day attack would be a surprise. And finally, night maneuvers increased tremendously the danger we presented to ourselves. So many armored vehicles, of different makes and silhouettes, feeling their way through the featureless and unfamiliar desert in the dark, and gunners inside with fingers on triggers, gunners who have never been in combat, waiting to meet the enemy, to shoot him before he shoots you. Slight deviations in routes or pacing could place friendly units in one another’s path. Unit identification symbols would not be visible, nor would the bright orange VS-17 floppy nylon panels we tied to the top of our tanks so the air force jets providing close air support could discern us from the other sand-colored moving blurbs on the ground2 (after the war I heard that Lieutenant Colonel Gordon had decided not to use close air support at all during combat to avoid the possibility of air-to-ground fratricide).

Ground Attack, Operation Desert Storm 24–28 February 1991

To close the briefing, Lieutenant Colonel Barrett repeated his stock heroic phrases: “high adventure,” “a night to remember,” “Lawrence of Arabia stuff.” I could hardly wait.

I didn’t know until researching for this book that the division’s planning for the offensive to liberate Kuwait from Iraq had begun the last days of August 1990, while well over half of 24th Infantry was still deploying to the Dammam port. Major General McCaffrey initiated this planning effort less than four days in country, as described by his division chief of plans, Maj. David R. Apt: “We were sitting at the port and had about half a dozen tanks on the ground…. We went up into a warehouse in an air-conditioned room because it was 120 degrees. We sat down and [McCaffrey] gave us his intent and [we] started planning from there.”3

At the battalion level, Lieutenant Colonel Gordon and his staff by late October independently “had the attack plan figured out, but did not anticipate the Seventh Corps deployment. That was my only real surprise. Mostly because I could not see why we needed them.” Nor did McCaffrey: “I thought in September or October the initial force could have recaptured Kuwait. I thought there was a degree of risk involved with it at the time, but I felt strong.”4

The one-corps plan devised by Schwarzkopf’s own planning team had not satisfied him, Gen. Colin Powell, Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney, or President Bush. Even with a two-week air prep, the one-corps option risked an unacceptable number of American casualties. It would surely succeed, only at too large a cost. By 15 October, Schwarzkopf directed his team to plan for a two-corps attack. On 8 November, the president announced the deployment of the Seventh Corps.5

The issue of an additional corps notwithstanding, our division leadership had foresight in spades. And I for one am thankful those other soldiers joined us.

The same day Task Force 3–15’s leadership received the briefing, Task Force 1–64’s operations officer, Maj. Jim Diehl, presented the plan at that task force’s staging area to the assembled commanders, platoon leaders, and first sergeants. Rob Holmes remembers maps posted all around the tent. As the leaders filed in, Diehl stood commanding the center of the tent, hands on hip, war face on, “in no joking mood.”

Rob relives his train of thought: “Second Brigade would lead the division. Wonderful. Task Force 1–64 would lead the brigade. Great. Delta Tank would lead the task force. Terrific. Second Platoon would lead the company. All eyes in the tent fell on me. My platoon had just been tapped to blaze the trail for the entire division.

“The news needed to be digested. The cliches raced through my head: No big deal. I’ll do the best I can. I’m just proud to help the team and serve my country. Why the hell me? also tore through my head. Being chosen was a compliment; though it could also mean that I was expendable. No. Captain Hubner and Lieutenant Colonel Gordon trusted me. Our country invests a lot of money and confidence in West Point officers. They don’t do it so that when we go to war, Academy graduates are two hundred kilometers south counting MREs and sorting mail. My new mission to lead the task force was what should be expected of me and those like me.

“I took a deep breath and, for the rest of the time I was in that crazy world, put on my game face. My responsibilities were never more clear.”

Greg Downey felt no small amount of relief that day in the briefing tent: “I had spent months watching our task force intelligence section plot the Iraqi army’s complex obstacle network on the southern border of Kuwait — three successive belts of mines, wire, and tank ditches. Some had speculated that the ditches were filled with gas to be ignited when we tried to cross. I had assumed we would attack through this nightmarish barrier into the jaws of the Iraqi army. Thankfully, we weren’t going near it.

“In my fledgling army career, I had grown accustomed to grandiose operations orders and graphics, with task force OPORDs reaching forty pages. Such tomes provided information about everything from where to be on the battlefield at a certain time to where to pick up logistics at what times. The Desert Storm OPORD was instead a seven-page list of Grid Index Reference System points. A GIRS point was nothing more than a map coordinate with an associated name, like ‘V25,’ which we would plot on our maps. With GIRS we could control unit maneuver and fire, quickly changing our plans and reorienting the force as new situations presented themselves.

“The simplicity of the OPORD attack plan made it easy to grasp at all levels. The mission statement from Lieutenant Colonel Gordon was as basic as possible: Task Force 1–64 Armor will conduct a movement to contact using the battalion diamond formation and conduct battle drills to defeat the enemy when encountered. Technology may have taken huge bounds from earlier wars, yet the human dimension of war fighting still thrived on simplicity. The soldiers may be smarter, but the simple plan is always the best plan when it is time to execute.

“The only question left was when.

“Walking back to the scout platoon after receiving the attack plan, I met Capt. Steve Winkler, my company commander.

“‘Hey Scout, I’ve got a new body for you. Meet S.Sgt. Hightower, fresh from Fort Benning. Been in Saudi for three days.’

“This was not what I wanted to hear. Since this guy was a staff sergeant, I would have to assign him as a Bradley commander and move one of my other BCs to a gunner’s seat. I had spent the last five months training my BCs, all of us coming together as a team, knowing how one another thinks. I rearranged my platoon to make room for Hightower, and had no sooner finished my first crash-tutoring session of my new BC when Winkler returned with four more soldiers.

“‘Jesus Christ, sir, why now?’ I fumed.

“‘These are combat engineers sent down from brigade to give us some engineer expertise in the scout platoon.’

“My scout platoon was rapidly growing at the worst time. I was not only concerned about getting unfamiliar soldiers into the platoon, but I was also trying to figure out how to fit their bodies and gear into the cramped vehicles, already overloaded from extra ammunition, extra scouts, and extra rations. I assigned one engineer to each of my three scout sections. I told my Bradley commanders to stow the new guys’ gear wherever they could. ‘Teach them the vehicle, how to fire the twenty-five mike-mike [25 mm], and as much about how we do things as possible. Then introduce these new guys to the rest of the platoon.’

“The battalion chaplain, Capt. Tim Bedsole, had been standing behind me when I used the Lord’s name in vain talking to Winkler. He always made me feel guilty about using foul language.

“‘Chaplain, I need a miracle,’ I stated.

“‘Maybe if you would pray to Jesus Christ instead of condemning Him for your struggles, He would answer,’ Chaplain Bedsole preached, in his slow, Southern Baptist drawl.

“‘Hell, Chaplain, I do pray … every goddamned day,’” I said, echoing my favorite line from the movie Patton.

“Bedsole laughed and asked if he could do anything for the platoon.

“‘I need you to help me with two things, Chaplain. One you can handle yourself, the other you’ll need the Big Guy’s help with. First, I’d like you to bless the scout platoon and the vehicles. We’ll need all the help we can get to survive this thing. We can’t do it on our own.

“‘The other thing is out of your hands, but I would appreciate it if you spent some prayer time on it. I want you to pray for guidance on the battlefield for my Bradley commanders, so they don’t get lost.’ I knew the chaplain didn’t understand my concerns about navigating in the featureless desert. He never had to deal with it.

“‘Lord,’ he began his blessing, ‘we stand here today facing the unknown, thinking about what our fate might be, what Your plan for us is. We ask that You provide protection for these young warriors, for they are being asked to give up their lives so that others may live, just as You had Your only Son give His life so we could live.’

“I looked into the eyes of my soldiers, seeing tears well up in many of them, feeling my throat tighten as I listened to the chaplain pray for us with every ounce of faith in his soul.

“‘And Lord, we ask that You guide these vehicles. Even though they are weapons of war, use them as instruments of peace, that they will bring this conflict to a quick end with as little destruction and death as possible. Look over these scouts, for they are the angels of the battalion, providing protection for over seven hundred other warriors. In Your name, we pray. Amen.’

“I tried to dry my eyes before looking up. The chaplain had finished the last precombat check I had on my list. I was thanking him for his prayers when I heard the voice that struck fear in most of the task force’s officers.

“‘Scout, Merry fucking Christmas,’ Lieutenant Colonel Gordon announced. He had a box under each arm. He looked at the chaplain. If Flash Gordon believed in God, he’d never let on.

“‘Now you don’t have an excuse about being lost. I hope you know how to use them,’ he said. He always laced his conversation with sarcasm.

I opened up the one of the boxes. Inside was a Trimpack GPS navigational device. The GPS calculates its position on the ground by signals received from orbiting satellites. Truly a gift from Heaven, and the answer to my prayers. Well, to somebody’s prayers.

“‘Damn, you work fast, Chaplain,’ I said.

“‘The Lord works in mysterious ways, scout,’ preached Chaplain Bedsole, grinning beneath his slight mustache.”

The next day, Rob Holmes happened to be at Task Force 1–64’s TOC when a contingency of replacement soldiers arrived, among them a group of officers. “I remember when the Humvee dropped them off — three second lieutenants and a captain. The captain, as friendly as he could be, shook my hand. One of the lieutenants asked if there was a chance for them to get a platoon. ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘if one of us dies.’ Their faces dropped. I don’t think it was from disappointment because they weren’t going to walk into a platoon. They realized we could die.”

Rob was right, of course. The new junior officers were there in case anything happened to any among the current set. Platoon leaders historically suffer more casualties than other soldiers since they lead the way. To position his replacement platoon leaders as near as possible to the platoons they might “get,” Gordon assigned two of the lieutenants as track commanders in the Tactical Assault Command, the handful of task force command vehicles that traveled in formation with the line companies. The third rode in a fuel truck with the support platoon. And he asked the new captain to volunteer to be the loader on his own tank, where he was as close as he could be to any company he might be called on to command.

I didn’t meet any of these men until after the war. I wasn’t even aware of their arrival, much less the purpose of their presence. Knowing my imagination, it was probably best that way.

■The week between the start of the air campaign and the western displacement to our attack position along the Saudi-Iraqi border was, except for the initial concept briefing, fairly uneventful for our two task forces. The war taking shape around us touched us only indirectly. In our daily updates, passed from commander to commanders to platoon leaders to soldiers, we received word of some of the events happening elsewhere in theater, mostly SCUD missiles fired at Dhahran, Riyadh, King Khalid Military City, and Israel; and limited ground action. One report from the Eighteenth Airborne chronology reads familiar, reads like I might have heard it before. It is the oddity of it: “Two unidentified individuals in SCUBA equipment are observed in the water near Warehouse #20 in the Port of Dammam; they disappear after being engaged by military police.”

Bravo Tank loaded its vehicles onto American HETs the afternoon of the twenty-fifth; as I vaguely recollect, we were one of the last companies in the brigade to make the move. The night before my company moved to the HET upload site, queues formed for the last sit-down latrines we would experience for an unknown period of time.

The loading area was a patch of desert off Tapline Road. The HET National Guard transportation unit hailed from my home state of Kansas. Their platoon leader, a woman lieutenant, found me after one of my soldiers told her I was from Kansas as well. I remember spying peripherally some of my guys, above and behind her on the tanks, making goo-goo eyes and obscene gestures while she and I made small talk. I remember finding her far too excited about the whole venture. More than likely she had not been living on her Humvee in the desert for the past five months; more than likely she would not soon be attacking Iraq. Maybe her giddiness was simple delight in meeting another Kansan halfway around the world. What were the odds?

Just as we had covered our vehicles’ identification markings before loading them on the ships (to hamper enemy intelligence) we covered the bumper numbers again for the move west.

We left at 1730. Near-freezing temperatures and rain for much of the night. We rode in the tanks on top of the HETs. I remember we had been briefed on the threat from enemy air: all those defenseless tanks arranged in rows for easy picking. So we had to ride in the tanks on top of the HETs, ready for the HETs to pull off the road and the tanks to come down. The two machine guns on top of the turret were locked and loaded, and one soldier per tank, an air guard, had to stay awake at any given time. When I wasn’t air guard, I passed the hours shifting around in my seat in a daze between sleep and consciousness. Before sinking into my daze, I chuckled to myself listening to the National Guard lieutenant on the radio. She was obviously a newcomer to the army radio net. She sounded like all of us did our first time in the field, articulating everything, not using voice recognition after the initial identification, not using radio shorthand, keeping the conversation going much longer than necessary. Such protractions fill the airspace and give the enemy the opportunity to track the signal.

We arrived at our download site at 0900 on the twenty-sixth. I was fortunate to have traveled for only fifteen and a half hours; Neal Creighton’s journey lasted nearly twenty-four. Back at the upload site, Dave Trybula’s company was just getting under way. Dave’s HET trip took a little longer than most: “My HET made it approximately halfway before too many of its tires gave out. We had to off-load the tank somewhere along Tapline Road. The HET went back for repairs, promising to send another to pick us up. So my crew and I sat. Out of radio range, we couldn’t inform the commander of our situation. We didn’t know where the company was, much less when we would meet back up with it. Late in the afternoon on the twenty-seventh, an Arab civilian stopped and asked if we were going to be there for another hour. I told him I expected so. He left and returned an hour later with a gigantic platter of chicken and rice. He said that this was his way of showing appreciation. My crew thanked him between gobbles of the steaming hot food. Late that night another HET finally picked us up, delivering us to the company’s laager early on the twenty-eighth. That morning was our first desert frost. The weather had indeed changed.”

The terrain at our download site, roughly 480 kilometers inland in the vicinity of the town of Nisab, stretched much more flatly than had our more coastal desert. The wind swept unimpeded; the weather was much colder. According to Greg Downey, we were some forty kilometers shy of the Iraqi border.

It rained incessantly the day my company arrived and throughout the night.

The next morning I spent huddled behind Greg Jackson’s tank against the cold, asserting to him that large, armored battles between armies belonged in history books. They had no place in the present.

The company spent the rest of the day bearing the wet cold, waiting to move.

As soon as his Bradley Cavalry Fighting Vehicles backed down off the HETs, Greg Downey’s scout platoon was ordered north to conduct a relief-in-place mission with a unit from the 3d Armored Cavalry Regiment screening the Iraqi-Saudi Arabia border. He had received reports that the 3d ACR had had sporadic direct fire contact with the Iraqis, most likely the platoon-on-platoon firefight the evening of the twenty-second recorded in the Eighteenth Airborne chronology, in which two or three 3d ACR soldiers were wounded and six Iraqis captured.

“I knew my FM radios would not be able to transmit back to the task force TOC, which would be over thirty-five kilometers away. Battalion told me to move out anyway, knowing that I could not both carry out my screening mission and keep the TOC informed. Battalion leadership fully understood the situation, yet failed to provide me any additional support.

“Once again I found myself caught in the army’s just-get-it-done mentality, which ignores the difficulties of the assigned task for the sake of getting started. I was just as often guilty of it myself, not wanting to hear why my intent couldn’t be done, instead just wanting to know when it was done. It feels worse when you’re on the receiving end of it.

“The scout platoon moved north until we arrived at the designated screen line. I was very confident in the navigation skills of each scout section now, as my section leaders had learned how to use the newly acquired GPSs. We occupied our screen during daylight, allowing us to find good observation locations that provided defensible terrain. I attempted to make contact with battalion throughout the night, but as predicted my radio transmissions could not reach the TOC. I even moved my vehicle south to reestablish communications, finally opting to abandon the idea and return to the screen line with my scouts where I belonged.

“At about 0300 hours, two Humvees arrived at my location. For the next fifteen minutes, I was on the receiving end of a one-way conversation with Major Diehl. We both knew the cause of the communications problem, but I did not want to argue and he did not want to listen.

“The battalion moved north the next day and joined us on the border. The task force staff developed a defensive plan for the slight chance that the Iraqi army would attack into our area. We would spend the next weeks conducting rehearsals, precombat inspections, and maintenance.”

■Late in the afternoon on the twenty-seventh we moved north to occupy our attack position. The brigade sat just south of the western edge of the neutral zone. Task Force 3–15 occupied the brigade’s and the division’s eastern flank, tying in with the westernmost unit of the 3d ACR, and formed a conventional horseshoe task force defensive position around an engagement area. Three kilometers north of Delta Mech’s position was the edge of the neutral zone. Eight kilometers farther, a long, manmade berm stretched along the actual “de facto” boundary between Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

The days seemed to be growing longer. Days of the week meant nothing. Dates meant little as well. Our sense of time stretched in both directions from H-Hour on G-Day, the time and date the ground attack would commence. Days leading up to G-Day became, say, G minus 3 (G-3), and subsequent days became, say, G plus 2 (G + 2). Not that we knew the scheduled G-Day date.

The evening of the twenty-seventh, I drew a sand table on the ground beside my tank and briefed the larger plan as I knew it to my soldiers. This was, as far as I knew, a violation of orders. They were not yet allowed to know.6 I felt I could not withhold any longer. The ground offensive loomed more likely with each passing hour, and they deserved to know the plan on which their lives depended. The knowledge appeared to comfort them.

We did not discuss the chemical or fratricide threats. The one didn’t need to be mentioned as it had been festering in everyone’s minds for the past six months, and the other, despite some training snafus, remained fairly inconceivable. That a friendly could shoot us meant that any of us could shoot a friendly, meant that we and our technology were fallible, and that we were far more vulnerable than we cared to admit.

The next afternoon, the platoon mounted up for our short trip to link with Delta Mech. As I led the platoon away from Bravo Tank, I radioed back to the XO. When you enter a unit’s assigned radio frequency, you must request permission. When you leave, you announce the fact.

“Black Five, White One.” Then Greg Jackson in that soothing, parade-announcing voice:

“White One, Black Five.”

“This is White One, leaving this net, over.”

“This is Black Five, roger, out.”

My stomach dropped. I flipped the radio switch to Delta Mech’s frequency and adjusted myself to my new call sign. Gold Six. The radio dials whirred into position, the antenna clacked to its proper, new setting.

Dave Trybula retells a story originally told to him by his commander, a story about our growing paranoia: “Division had discovered a series of fifty-five-gallon drums on a north-south trail right at the Saudi-Iraqi border, and suspecting that the Iraqis might have filled them with nerve agents or foo gas, sent a team to check them out. Dressed in MOPP IV — chemical suits, masks, and black rubber boots and gloves — the team sent one man to the nearest drum while the others watched. He kicked the first drum and ran back to the others. He made his way back and kicked a second drum; then a third. A Saudi border patrol had been watching them and drove up. The team from division tried to wave the approaching Saudis away, to protect them from the danger. The Saudis didn’t understand. They pulled up to the team. When a member of the team explained the situation and asked the border patrol to remove themselves to a safe distance, the border patrol laughed. Saudi Arabia had set up the drums years ago to stop people from inadvertently crossing the international border. The drums were full of sand.”

According to my letters, I finished Henry James’s The Americans the afternoon of 29 January. Of the several books I read in the desert, The Americans is one of the most discussed in my letters. It is also the only book I had entirely forgotten having read until I reread my letters for the first time since the war, writing this book. As for my present memory of the novel, of plot, of characters: nothing. After finishing it, I dropped the novel into the bury pit beside my tank.

I did not feel the boredom as severely as my soldiers did. In addition to my escapist reading and letter writing, I had leadership duties. I met at least daily with Captain Baillergeon and the other lieutenants. I also had maps to assemble. So many maps. Whereas at the NTC in the California desert, where we conducted our most expansive maneuver training, we dealt with at most four map-sheets for our run across the Arabian peninsula we had over thirty sheets to manage.7 Connecting eight of these three-foot-square mapsheets as required would have made a six-by-twelve-foot monstrosity. I instead grouped my maps only one sheet high, enabling easy accordion unfolding and refolding. The entire bunch, once assembled and marked with operational graphics, I stuffed in marching order in my map satchel, which rode in the sponson box beside my hatch. As we attacked I would swap the map group in my hand with the next one in the satchel. In addition to the thirty-some 1:50,000 maps, we also carried a set of 1:250,000 maps showing the entire division maneuver plan. At the battalion and lower levels, we were accustomed to the 1:50,000 and the even more detailed 1:25,000 scale. The world of the small unit leader is the world of individual draws, spurs, wadis, berms, creeks, powerlines, and the subtlest of elevation changes. The more details, the better. But even on a 1:50,000 map, a blank expanse could be a mess of berms, gradients, and depressions, difficult to navigate and easy hiding for the enemy.8

The map satchel bulged with its cargo. The roll of some 250 remaining map sheets I stored in a tank main gun round shipping tube tied outside the bustle rack on the turret rear. We would need these maps in case our battle plans changed.

The sound of firing artillery rounds interrupted my map making on 30 January. Rounds leaving tubes: a dull hollow sound, the successive distant thuds forming a single rumble. It must have been the first ground war action I experienced. I am remembering the sound came from behind us, possibly from 3d ACR; I do not know.

To my west, in 1–64’s tactical assembly area, Dave Trybula was penning a letter to his girlfriend Jill: “I have been keeping very busy trying to make sure we’re ready for anything. This is the only thing that scares me — that I will send men to their death because of a mistake I will make or because I forgot to train them in some way. This is something that will always remain in the back of my mind.”

Before the arty salvo, I watched a butterfly alight upon the ground between me and a showering Sergeant Dock. After the artillery another gorgeous sunset capped my day. The sun left vibrant peach-pink airbrushed clouds in its wake.

That evening’s intelligence update dashed the calm. The night before, Iraq had conducted preemptive ground incursions out of Kuwait into Saudi, in the Marine Corps sector on the coast. One part of the attack involved a tank battal ion; one (it may have been the tanks) penetrated the border and seized a Saudi coastal town, Ra’s al Khafji, located about ten kilometers from Kuwait, before being repelled. I noticed more air sorties than usual that night. We received a warning order for an on-order mission to displace south one kilometer, to allow an MLRS unit to move forward to fire its missiles deep into Iraq. The move would remove us from the MLRS danger area.

The on-order displacement mission did not come.

Intelligence update about the assault on Khafji came the next day: American A-10s and B-52S had hit a seventeen-kilometer-long Iraqi column moving south, destroying two hundred tanks. We would not learn until 10 February that during the fight for Khafji, a U.S. Air Force air-to-ground missile may have destroyed a Marine Light Armored Vehicle, killing seven.9

The soldiers can take the unrelieved tension and the unrelieved boredom only so much. Then they outburst. On 3 February, it was my driver, Pfc. Reynolds. He clambered out of and off the tank, where he had been hiding from the wind, and onto a small pile of rocks, where he shouted “Bullshit!” at the top of his lungs. He returned tankside, under the bustle rack, out of the wind and sun, and sat next to me on a grease can. “Waiting is bullshit.”

I tried to explain my position, how waiting increased our chance of living.

“Waiting is bullshit, sir. We should have attacked back in October. Gotten it over with. Surprised him.”

I explained that in October, we had had one mechanized division on the ground. Ours. I reminded him of the state of our old M1IP tanks we had brought from Stewart, of our operational readiness, in October. Attacking, I felt, would have amounted to suicide.

“So? We’d be home one way or another by now.”

“Doesn’t it matter that you go home alive?” I asked.

“As long as I go home.”

“Then if you’re tired of waiting, and if life means nothing to you,” I challenged, “why don’t you just put your .45 to your head and blow it off?”

Just then Sergeant Dock emerged from the tank. With blue ink he had scrawled “FUCK” on his forehead and “IT” on his chin. He paraded himself around to the other tanks, giggling to himself. Sergeant Dock, my gunner, the NCO in charge of my tank, for that instant no icon of small-unit leadership but a living monument of the soldiers’ frustration.

I suspect my soldiers sensed my fears about battle. Maybe my evident terror was counterbalanced by my continued presence, my willingness, and my surface equanimity, the whole effect serving to mollify their own fears. A case of unintended leadership by example: Look at the lieutenant, he’s scared too, and he’s okay. Maybe not.

Pvt. Doug Powers caused one of my most troubling moments during the final weeks preceding the ground war. He came to me one day because he was scared. Powers loaded for Sfc. Freight. He didn’t trust Freight. “Sir, he doesn’t know what he’s doing. Sergeant Wingate does half Freight’s job for him, and Wingate is frustrated because he’s been a tank commander before, he knows he’s better than Freight, yet he can’t command the tank from his gunner’s chair, and I know he worries that Freight will get us killed.” The respectful private would not explicitly label his platoon sergeant a moron or idiot; he approached me with his own problems, not Freight’s. He was the most professional nineteen year old I’ve ever met. A few days earlier he had restored the morale of Sergeant Boss, a pissed and despondent NCO who had refused to leave his gunner’s position for three days, not speaking to a soul. I left him alone, in the hope that his hibernation was gestating an improved psyche. Boss emerged when Private Powers asked for help writing a letter. In the “To Any Soldier” letter lottery, Powers had won. He corresponded with several pretty girls, one gorgeously cute Texas blonde, the twenty-year-old Miss Melissa, who promised to take him to dinner when he got home. Powers was from Texas, too. From his first letter to these girls, Powers had entreated Boss’s assistance, which the latter confidently provided. As I write, I wonder if Powers really needed Boss for a letter that day, or if the young man knew better than I did what Boss needed: a gesture of respect from a subordinate, an invitation for Boss to assert himself in both a manly and sensitive way. After the letter, the sergeant was his old self.

I did my best to assure Powers that his life hardly depended on Sfc. Freight. He had three other tanks in the platoon looking after his, and ten other Bradleys in the company. His tank would never be alone against the Iraqis; his tank would never be without the rest of Second Platoon. I don’t know how much comfort I afforded Powers. I liked and respected him — he was the most able, mature, and amiable of my enlisted men. Facing him then deluged me with feelings of sympathy and helplessness and fear and outrage, and left me numb.

My personal campaign to relieve Freight persisted until G-Day, if my efforts had waned for want of response. On one of those final February countdown days, Freight boasted to me about the gang rape of a young woman soldier he had orchestrated in the backwoods of Fort Knox. I think he said she was the training battalion colonel’s Humvee driver, with whom she had been having an affair. “She was a real tease, sir, to the rest of us; she deserved what she got. I had her drive me out to where the road ends in the middle of nowhere one night, told her to put out or get out. Had her drop her pants, bend over and lean up against the vehicle, and took her that-a-way. From behind, know what I mean? Meanwhile, what she didn’t know, I had me a bunch of my buddies follow us, and as soon as I finished with her they had their turn. Learned that girl a lesson, and she liked it, too. Yes sir, she sure did like it.”

I did not believe him for a second. Freight lied to impress. During our month with the Cav, my tank crew and I overheard him telling Delta Mech’s 1st Sergeant Burns that, like Burns, he had been in Vietnam. Freight had never mentioned this to anyone before. Nor did he wear a combat patch on his right shoulder for the unit in which he claimed to have fought. Burns asked him his Vietnam unit. Freight scratched his head. He’d forgotten. Burns asked for the nearest village to Freight’s unit’s base camp. Freight stroked his chin. He’d forgotten that as well. As if a combat veteran still in possession of his mind could ever forget his wartime unit or the ground he’d fought over. I have never seen a person’s mouth as wide open in disbelief and hilarity as Pfc. Vanderwerker’s as we eavesdropped. McBryde sat on the turret top giggling through his Cheshire grin. Between his own suppressed outbursts, Sergeant Dock called Freight a “stupid fuck.” All three watched me as they listened and held back, quietly ferreting my response.

Four months later, newly armed with a rape confession, I reported to Captain Baillergeon. “The UCMJ statute of limitations for a felony is five years, right, sir? I’d like to court-martial him.” I did not expect Baillergeon to take me seriously. It gave him and the other officers a good laugh while giving me the opportunity to broach the tired subject again. Baillergeon agreed to mention it to Lieutenant Colonel Barrett once more. I had no reason to be hopeful.

■My letters of late January and February talk more and more of my homecoming. One to my Philadelphia belle lists my repatriation plans in ironic imitation of our offensive operations order: Repatriation Day (R-Day), fly to Kansas City. Buy convertible; drink with friends. On R+5, the fifth day after repatriation, Maria flies to Kansas City. R+7, drive with Maria to Philadelphia. Et cetera. Another chats on the new clothes I would need to buy those first days back. I wrote about graduate school. I drool for school. I spent more time thinking about my homecoming and postwar life than I did about the war. I still find myself fighting my position and circumstances, I wrote on 27 January. I do not want to lead men into battle. I want nothing to do with the things leaders do. I must change my state. I must plan, and assemble maps, and consider.

Letter of 12 February: We hear and feel the bombing occurring fifteen miles to our northeast, in another unit’s sector. At night we see the flashes.

At least once a day a pair of helicopters buzzed overhead on their way north.

Always in the back of my mind were the news articles and radio stories, and letters from home about articles and radio and TV stories, in which “our pundits” predicted that the upcoming ground war “will be the bloodiest battle since Normandy,… akin to the battle of Verdun, fighting through the fire trenches, on and on.” That’s how Major General McCaffrey summarized them.10 He and others may have known better, but we did not. We could not. Any reassurance our leadership might have given us — I remember nothing specific — would have felt like exactly that: mere reassurance from our leaders. A pep talk about a plan we weren’t supposed to know.

Rob Holmes and his fellow Delta Tank platoon leader, Jeff White, paid me a surprise visit the next day. They drove their commander’s Humvee, having just come from visiting Neal Creighton in Alpha Tank. Rob made that trek, he writes, because he “had recently learned about leading the task force, and to be completely candid, I was a little nervous. To this day I maintain that I never once thought I would leave the Middle East with so much as a scratch on me. I don’t say that with bravado. My father was raised Southern Baptist, my mother Lutheran, and I went to an Episcopalian elementary school and a Catholic high school, and as a Presbyterian I believe in a sense of purpose and destiny. This all can’t be an accident. Whatever my purpose is, it wasn’t to die in that damn desert. I was, however, absolutely terrified of getting one of my guys hurt. I couldn’t bear the thought. I guess that’s why I was a little bit nervous before we attacked, so I wanted to see Al and Neal. I didn’t know if they were nervous also, but I figured it would help me if I could shake their hands before we launched, and maybe it would help them as well. It wouldn’t have been in my character to have told them at the time why I came calling, but that’s the reason. Confidence is contagious, and there is strength in numbers. I knew they were on my flank, and that made me feel better; I guess I just wanted to make sure by actually seeing them before we attacked.”

BBC report on the radio, 16 February: Hussein offered to follow UN proscriptions, and Bush restated his position to continue bombing until Hussein begins to withdraw or unconditionally surrenders. Two days later, Tariq Aziz (ironically enough a Christian), given Hussein’s calls for a jihad against the largely non-Muslim forces gathering against him,11 met with Mikhail Gorbachev, the latter trying to convince Iraq to quit the field. We heard about the meeting at a commander’s update the following day. Aziz and Gorbachev met several more times until the start of the ground war, teasing me, stringing me along. I don’t remember when I resigned myself to the war’s inexorability.

Some time during or just before the air war, I heard that a group of American citizens threatened to form a human shield between Kuwait and Saudi Arabia to try to stop the war. Our commanders’ response: The desert is a big place; we’ll try not to run anybody over.

Prior to the air war, Dave Trybula had received two reports that bolstered his confidence and his soldiers’ morale.

“First, we were told that the Iraqi front-line tanks carried the same basic load of ammunition as they had at the end of the Iran-Iraq war. This meant that most of their tank rounds were antipersonnel and not antitank, since the Iranians had few tanks and had relied heavily upon human assault waves. In other words, these battle-proven warriors with these awesome tanks were handicapping themselves by basing their ammunition loads on their experience against Iranian infantry rather than on intelligence of our armor. Second, we were informed that while Iraq bought their tanks from the Soviet bloc, they made their own ammunition to save money, and tests done on it showed it to be so substandard that it would require an extremely close shot, and a lot of luck, to damage our tanks. It didn’t seem to matter anymore that their tanks outnumbered ours two or three to one. This great news increased everyone’s desire to get across the border and finish the job we had come here to do.”

Two different pieces of information assuaged my own fatalistic mood those final days before the ground attack. Captain Baillergeon shared classified information with me, assuring me of the Abrams’s superiority over the T-72, Iraq’s most modern tank. “You don’t have anything to worry about.” He had the information firsthand — that was all he could tell me. And a BBC report estimated 30 percent of Iraqi tanks and 40 percent of Iraqi artillery had been destroyed during the allied air campaign. I swore I’d buy a drink for every air force pilot I ever met.

We were briefed once, at our final assault position in front of the berm, on possible enemy locations along our route. At Task Force 3–15’s TOC, the task force leaders walked through our actions on meeting the enemy at each of these locations on a sand table. Lieutenant Colonel Gordon conducted a similar session over in Task Force 1–64. According to Greg Downey, this “battle-drill rehearsal ensured everyone in the task force knew, in detail, how he fit into a battle. All vehicle commanders, both tracked and wheeled, and gunners, drivers, and battalion staff participated. The terrain board was the largest I had ever seen, covering one full square kilometer. With each vehicle’s crew walking the terrain board, every formation was rehearsed, every battle drill executed, every contingency exercised. The battle drill, the most basic and essential form of fighting, was validated in the minds of every soldier there.” After 3–15’s sand table walkthrough, the air force air liaison officer (ALO) assigned to the task force passed out copies of leaflets being dropped on the Iraqis. After dropping a five hundred-pound bomb inside a crate floating down on a parachute, we dropped an identical crate-parachute configuration, which upon bursting rained leaflets down on the shocked, cowering troops. (An army guy joshed the ALO: “M113S don’t have ejection seats, captain.” A mild titter went a long way in the desert.)

In that final week, Captain Baillergeon distributed to his platoon leaders a number of photocopied sketches. Most of these consisted of task force positioning at various objectives along the route. One of them depicted our entire route, the known Iraqi units to our east, their estimated strengths, and the approximate time it would take them to reach us. The closest, the 26th Division, had all of thirty-five T-55 tanks, the oldest brand in Iraq’s — in anybody’s — inventory. Task Force 3–15 alone had twenty-eight M1A1s. Most of the sketched units fell into Seventh Corps’s avenue of advance. I was more concerned with our destination north of Kuwait, when we would find ourselves sandwiched between Iraqi forces in Kuwait, both those in defensive reserve and those retreating, and Iraqi reserve forces in Iraq. Hussein held his elite divisions, his Republican Guard, as his reserve force. Rob Holmes shared my concerns, as did I imagine nearly every soldier in the 24th: “If we did not make it to the Euphrates River before the Iraqi army, we could wind up chasing the Republican Guard to Baghdad. And if the American and coalition forces to our east were not effective pushing the Iraqis out of Kuwait, we would be deep in enemy territory, tethered to a long and vulnerable supply line.”

Task Force 3–15 practiced crossing the border the evening of the eighteenth. We did this by literally rotating the graphics one hundred eighty degrees on our maps in order to execute the practice mission to our rear in the south. All the Bradleys and tanks, and a representative portion of the battalion train vehicles, participated. The mission took place at night and was a fiasco. It ended after the task force failed to regroup on the other side of the make-believe berm and when, cruising through a flat tract of desert with half the task force behind me, I lifted my PVS-7 night vision goggles and an American attack helicopter filled my view. I hollered at my driver to make a hard right; we dodged the thing, then we stopped. I look around with the PVS-7S — we were surrounded by attack helicopters. I did not want any of our tanks or Bradleys to smash an Apache days before the ground war. Captain Baillergeon agreed. We abandoned the mission. It was 0200.

The next morning, winding our way out of the area, we passed a support unit. They had themselves a regular camp: vans, tents, showers. All the luxuries we had left behind, and here they were just kilometers south of our position. The support soldiers, dressed in T-shirts and baseball caps, waved to us. Not a weapon, helmet, or flak jacket in sight. I cursed them to my crew over the intercom: “You should see these fucking REMFs.”

Greg Downey could feel the tension mounting in his scouts as the days ticked down to war. “Everyone had been ‘leaning forward in the saddle’ for an extended period of time, waiting for the big moment. A person can only take so much before lashing out. Perhaps it had more to do with impatience of getting this over and going home than anything else, but I began to truly and deeply hate the enemy. We had been in Saudi Arabia over six months, enduring the austere conditions, waiting for something to happen to justify our presence. Seeing pictures of the Iraqi soldiers demonstrating, and burning American flags, really fueled my fire. If Iraq withdrew from Kuwait now, it would be a bittersweet victory.”

It rained fiercely over the night of the nineteenth. I initially mistook the thunder for artillery. We slept in fetal curls inside the tank. When we emerged the next morning, we found our tank sitting in a small lake. Brian Luke, Delta Mech’s first Platoon Leader, who had slept in his customary manner underneath his Bradley, woke spitting up water and had to swim out from under his Bradley. He and I talked as his troops used the heat from our engine exhaust to dry their gear. Despite the wet, we were somewhat thankful for the rain. Rain sucks for the soldier, but it also refreshes him. It always changes his spirits; afterward, he always smiles broadly. We were also thankful because G-Day approached, and a thorough soaking of the ground would help keep the dust down, out of our faces, out of our gun sights.

Gorbachev and Aziz resumed talks on the twentieth. Knowing the ground war imminent, Gorbachev desperately wanted a cease-fire. Bush and Italy’s president urged Russia and Iraq to hasten their process. Ground forces were awaiting Bush’s order.

The next day Rob, Jeff White, and their company’s artillery fire support officer, Mike Francombe, visited again. All three were excited by the Gorbachev-Aziz peace prospects. Flash, they claimed, no longer believed we were going to war. Was he disappointed? So many girls had called Rob’s parents about him that his mother had to take notes to keep track of them all. Rob had written me a letter on the eleventh, which I did not receive until after this second visit. If we did not attack until March or April, he reported in his letter, there was some talk of my becoming his company’s executive officer. That would make me the company’s second in command, over Rob and the other platoon leaders, and the acting company commander if something happened to the captain. He also wrote about how we might be out of the army in time for graduate school in the fall of 1992, which meant we’d have to start taking exams and applying in the summer of 1991. “That’s as soon as we get home! We’ll have to sober up pretty quickly after our homecoming because we have work to do…. Well, Al, it looks like we’re going to war. God be with you…. When it comes down to it, West Point exists to produce young men to lead such missions. We’ll be fine. See: II Timothy 1:7, Romans 8:29–38. Take Care. Rob.”12

Cross-Border Operations: 21–24 February 1991

CBS had a segment on about the nucleus of our war machine. In case you have had the impression that none of us know what you are going through, the network special was about you. They talked about the 23-year-old M1A1 commander and the necessity for the effort of that young man, and his ability to think quickly and correctly. They called you the “most vital link” in the weapons system. Must give you an awesome sense of power to know that you are that important.

On 21 January, the Eighteenth Airborne Corps directed its major subordinate commanders to plan deep operations in preparation for the ground offensive. The 24th Infantry Division’s plans for these cross-border operations — what The Victory Book calls “intrusive reconnaissance operations” — command an entire section of the Historical Reference Book’s five sections. It is easy to forget that the ground forces were at war prior to G-Day on the twenty-fourth. Forget is not the right word. Those of us on the ground lived largely unaware of the action taking place on the ground around us and elsewhere in the theater. Though the Eighteenth Airborne Corps’s chronology has significant omissions, it nonetheless portrays a busier and more dangerous pre-G-Day period for coalition ground forces than I had believed. This action intensified on 15 February, when the corps commenced its cross-border operations: attack helicopter raids, air assault raids, A-10 air strikes, psychological operations, artillery missions, Special Forces and LRSD insertions, and mounted armored incursions, all to gain intelligence and to eliminate any resistance on the other side of the border that might slow our attack.

Neal Creighton participated in an artillery mission against a border post in the first hours of 21 February. Neal’s fire support officer targeted the building for a single 155-mm copperhead round. “I will always remember how accurately the copperhead struck the building. Dead center.” A dismounted patrol from Neal’s company cleared the site. “All that was found in the rubble,” reports Neal, “was a pair of scorched boots.”13

Around 2000 that evening, Captain Baillergeon called the company to REDCON 2; our scouts had spotted enemy vehicles and possible artillery pieces in our sector. We put our sleeping gear away and moved to our crew positions. A little later, Baillergeon reported that four SCUD missiles had impacted to our east. At 2400 we returned to REDCON 3. The sleeping bags came back out. As I went to bed I heard a series of four bomb rumblings.

Meanwhile, Greg Downey was on the first of his two cross-border operations. “The three scout platoons in 2d Brigade would conduct zone recons from the Line of Departure to Phase Line Opus, about twenty kilometers north of the border. The purpose of this zone recon was to identify any enemy positions and gather information on the terrain. First we conducted a dismounted recon of the berm along the border to determine a suitable crossing site. Just after darkness fell, we crossed into Iraq.

“As my CFV drove over the berm, my driver Specialist West reported over the intercom that the engine was running hot. A few seconds later flames shot out of the engine access panels and for a split-second engulfed West. After stopping to extinguish the oil fire with handheld fire extinguishers, we determined the fan tower had seized up. I transferred over to my wingman’s vehicle, moving its commander to the gunner’s seat. I sent my own Bradley back over the berm. My first combat mission was getting off to a rough start.

“The zone recon was very controlled. The brigade headquarters coordinated the movement of all three battalion scout platoons to ensure we stayed on line as we moved north. Because the whole task force was listening to our radio transmissions, we tried to give a good picture of the terrain and any other intelligence we could gather.

“Even though we had been at the border for weeks and not seen any enemy activity, I had an eerie feeling running through my body. We were on the bad guy’s turf now, waiting for him to see us, waiting for him to start a fight. The terrain took on a life of its own: Rocks looked to be moving, vehicle tracks looked recently drawn, dust clouds seemed to be fresh. My eyes strained as I peered into the darkness, looking for any indication of movement. Every muscle in my body was flexing, anticipating a sudden encounter with the enemy.

“‘Sir, I’ve got a moving target… range two thousand meters,’ Staff Sergeant Hightower called from his gunner’s seat.

“My stomach moved into my throat. As I crouched down into the turret to look through my thermal sight, I radioed my platoon to take cover behind available terrain and occupy a hasty defensive position. I then called the report to Lieutenant Colonel Gordon. The vehicle put off a heat signature like a BMP-1, a very common vehicle in the Iraqi army. Every gunner in the platoon had his finger on the trigger. Since I wasn’t sure if it was friendly or enemy, I instructed the platoon that only my vehicle would fire. I received ‘affirmatives’ from Red and Blue section leaders.

“The lone vehicle was traveling straight south at a high rate of speed. We soon clearly identified it as an M3 Scout Bradley. The thermal sights in the M1 tank and M3 Bradleys convert heat from the source into a visual image with amazing details. The closer you are to the source, the more vivid the image. I alerted brigade, who reported that all friendly scout vehicles were accounted for. I knew better. This CFV was heading directly through my zone and threatened to cause an engagement between two friendly forces. I had my platoon back down into hide positions, totally masking their vehicles behind terrain, and let the vehicle drive by. The lost Bradley CFV sped right past my vehicle and a near disaster had been avoided. Thirty minutes later it crossed back into Saudi Arabia in my task force’s zone. I later learned that when the Bradley’s commander realized he had been separated from his own scout platoon, he shot an azimuth straight south and raced back to the border.

“We continued to Phase Line Opus and set our screen. The scouts were pumped. Without a word from me the platoon established local security, wired hot loop communication between section vehicles, and checked vehicle maintenance. We screened until 0430 hours, then returned south before the sun rose. After debriefing the brigade staff, we returned to the border.”

■Sergeant Dock and I were warming ourselves behind the tank just after stand-to on the twenty-second when we heard thuds to our north and east — very close, closer than anything previously, anyway. Then we saw to our front the flashes of rounds landing, maybe ten miles north. But this was difficult to know given how sound and light travel across the desert. The barrage continued about forty minutes, thuds on the right and up front, the quick successive thuds of intense bombing. And the light — at first single flashes, then flickering as if we were watching a fire through a screen. This all in conjunction with the rising sun. The thuds petered out in pairs.

Sometime during the course of morning I learned the date set for G-Day: 24 February. In two days. I presumably also knew by this time that the plan had changed, and the division was not scheduled to LD until the following day, G+1, on the twenty-fifth. Rivera reported the news of widespread disease and misery among Iraqi citizens and soldiers — he had his news from his contraband radio. Hussein had agreed to Gorbachev’s withdrawal plan and terms, and though these did not include all twelve conditions in the UN Resolution, Iraq would return all POWs immediately. The decision fell to President Bush.

That night my company, Delta Mech, executed a cross-border operation mech pure — without my tank platoon, that is. Bradleys only. My tanks were attached to Bravo Mech, in an overwatch position, platoons on line, in sight of the berm that demarcated the border, in case Delta Mech needed us.

Shortly after Delta Mech crossed the berm I saw Bradley 25-mm tracers zip across and ricochet off the struck object into the air. A second burst followed, and then nothing. I hooted, beat my hands on the tank. The adrenaline flooded me. I wanted to get the call, I wanted to fire up my tanks and charge through the breach. The way a humid summer day swells and swells and swells until at last it breaks, and the rain pours — that was how I felt, after the months of Desert Shield, the swelling pressure, and then to finally fire on the enemy.

Mixed reports followed. The firing gunners swear they saw troops in a truck and had actually waited to fire so that one of them could finish urinating and return to the truck. Others on the mission saw nothing. No evidence of enemy vehicles in the area was found.

I didn’t know that other units were also operating across the border that night. Greg Downey’s scout platoon was conducting another zone recon to Phase Line Opus to set up a screen for the night while Alpha Mech established a hasty defensive position three kilometers to his south. According to Greg, “the brigade’s other two battalions, Task Force 3–69 Armor on our left and Task Force 3–15 Infantry on our right, would also be sending units to Phase Line Opus; only 3–15 was sending an M2 Bradley infantry company without its scout platoon.

“My scouts crossed the border at 2000 hours. My CFV had been repaired that day, so I had my crew back. We had moved about two kilometers into Iraq when Red Section, my right flank scout section, came under direct fire. I saw the rounds before Staff Sergeant Deem, my Red Section leader, contacted me. The fires were coming from the right rear of the section. I saw the familiar red tracer rounds impacting as I had seen on so many gunnery ranges. We were being engaged by friendly units. The Iraqis used green tracers.

“Deem stayed pretty calm as he maneuvered for cover. Wiggins, Deem’s wingman, panicked. ‘Black One, this is Red Three … I’m pinned! I’m pinned!’ He was terrified. I was already on task force command frequency telling the TOC to tell 3–15 to stop shooting us up.

“‘Jesus Christ, sir, we’re taking fire!’ screamed my driver, already trying to pull down into the low ground. I had just completed the transmission when my own section started receiving fire. Rounds were impacting around my CFV, kicking up dust and flying above my turret. I wanted to move forward to low ground, but a 25-mm round skipped off the front deck of my vehicle, making a zinging noise and sending sparks jumping into the air.

“‘Get us down low,’ I told West.

“‘I can’t see over this ditch — it looks like it’s deep,’ West spat back.

“‘I don’t give a shit how deep it is, get down into it!’ I yelled, ducking my head low into the turret.

“My vehicle felt like it fell off the face of the earth as it poured over the edge. It crashed to a sudden halt when it reached the bottom of the ravine. Not a very graceful landing, but a safer place compared to where we had been. Once my CFV stopped, I tried to piece everything together. I got Lieutenant Colonel Gordon back on the net. He confirmed that a 3–15 infantry Bradley platoon had acquired and pinned two-thirds of my platoon down. It took five minutes before 3–15 got the Bradley platoon under control.

“I was more angry than scared. My biggest fear had always been not being killed by the enemy but being killed by our own people. It’s probably the biggest concern for all scouts, knowing that the likelihood of being shot from behind by a friendly unit is better than being engaged from the front by the opponent.

“Task Force 3–15 was claiming that their infantry platoon had fired on a truck, but the only thing at that location was my scout CFVs. A big contributor to this near-fratricide was the fact that 3–15’s scout platoon sat out the mission, so that a combat unit had been allowed across the border with no recon assets. Evidently, some nervous gunner or Bradley commander saw us moving and was not clear about the missions of flank units.

“Wiggins regained his composure. I was still fuming about the whole incident but pressed on with the mission. Alpha Mech had been crossing the border when my platoon had been engaged. It took a few minutes to get everyone focused again before we moved north to PL Opus.

“We returned south and back across the border early in the morning on 23 February. Once again, we debriefed the brigade staff. Col. Paul Kern, the brigade commander, was not happy about the friendly fire incident. He made himself very clear: It would not happen again.”

The first time I read Greg’s account, my stomach turned over, and my skin turned cold. What I had been so ecstatically cheering could have been his death.

■President Bush had given Hussein until Saturday the twenty-third to pull his army out of Kuwait. I wrote only a brief note to Maria that day. Believing that we would not LD until the twenty-fifth, at G+1, I concluded: Like the rest of the world, we go to work early Monday morning. But Greg still had one more cross-border mission, this one with Rob Holmes’s Delta Tank.

“Lieutenant Colonel Gordon visited me a few hours before the next mission. I was dumbfounded by his behavior. He was very complimentary, almost friendly, showing a side of himself that I had never seen or knew he was capable of.

“‘This is the best scout platoon I’ve ever worked with. Your maneuver and control is great. Keep up the good work.’

“I was speechless. I think he was finally at peace with himself, knowing that he would be going into battle.

“I went over the details of the 23 February mission with Capt. Dave Hubner. Since his Delta Tank would be the most forward company in the task force formation during the attack, I had worked closely with him throughout Desert Shield. Hubner intrigued me. On the outside he looked like a big lug, the guy you see at a party carrying the beer keg on his shoulders and drinking straight from the tap. But he proved sharp as a tack, extremely intelligent, and quite knowledgeable.

“I was starting to feel the lack of sleep from the past three days. Little rest goes hand in hand with being a scout, but anything less than four hours a day over an extended period of time invites trouble. Captain Hubner’s tank company was very well trained, making me more confident that no mistakes would occur. The mission was the same, a zone recon to Phase Line Opus, where we would establish a screen. But this time we would not return south. We would occupy Opus until the rest of the task force joined us on the twenty-fifth for the attack.

“The zone recon to Opus was uneventful. No surprises. Though after getting shot at the night before, I kept thinking about the tankers behind us seeing my scout vehicles in their thermal sights. A very uncomfortable feeling I had better get used to.

“As the sun started to rise over the horizon, I looked out across the desert. This was the first time I had seen this area in the sunlight, even though I had spent the last three nights here. It didn’t look as dangerous or eerie as it did in the dark.”

Rob Holmes led Delta Tank’s move across the berm. Delta Tank had an infantry platoon from one of the Mech companies attached to it for the night. It was 1900 hours when he received the call from Captain Hubner. Rob replied in kind:

“‘Black Six, this is White One. Sabers ready, over.’ My voice broke the silent night as I radioed Hubner to let him know my platoon was ready to roll.

“‘This is Black Six, roger. Execute.’

“With this brief transmission, my M1 moved forward from our attack position and approached the berm. Tanks don’t like crossing over hills because it exposes the soft underbelly, so our engineers had blown a hole in the berm that we could pass through. My other three tanks followed and formed a wedge behind me. Captain Hubner followed my platoon, and the rest of the company trailed him. Radios were silent. I searched for the military police escort that was to lead us through the friendly reconnaissance units in front of us and to the breach in the berm. This drill is called a passage of lines and was particularly dangerous because as we passed through friendly units everyone was trigger-happy and tense. Coordination and communication had to be perfect. Before mounting up, I had tried to joke a bit with my tank commanders to loosen them up. Now that we had to be quiet on the radio, there wasn’t a whole lot I could say to keep people calm. I had to rely on our training to give my men the confidence to do their jobs.

“I looked forward to crossing the berm if for no other reason than because once we were on the other side, anything that turned up ‘hot’ in our sights was enemy.