IT WAS THE month of October 1922, at about five o’clock in the afternoon. The principal square of Clochemerle-en-Beaujolais was shady with its great chestnuts, in the center of which stood a magnificent lime tree said to have been planted in 1518 to celebrate the arrival of Anne de Beaujeu in those parts. Two men were strolling up and down together with the unhurried gait of country people who seem to have unlimited time to give to everything. There was such emphatic precision in all that they were saying to each other that they spoke only after long intervals of preparation—barely one sentence for every twenty steps. Frequently a single word, or an exclamation, served for a whole sentence; but these exclamations conveyed shades of meaning that were full of significance for two speakers who were very old acquaintances united in the pursuit of common aims and in laying the foundations of a cherished scheme. At that moment they were exercised in mind over worries of municipal origin, in which they were having to contend with opposition. And this it was that made them so solemn and so discreet.

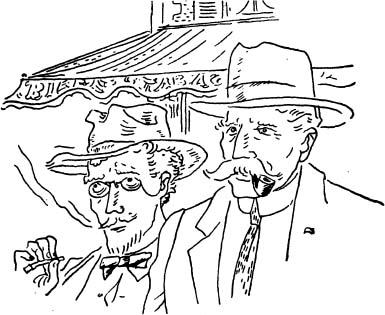

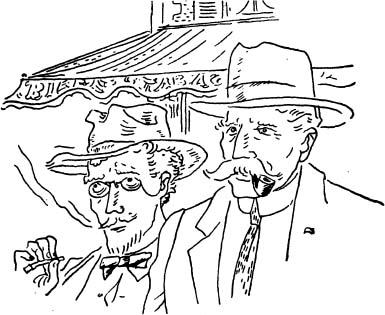

One of these men, past fifty years of age, tall, fair-haired, of sanguine complexion, could have been taken for a typical descendant of the Burgundians who formerly inhabited the Department of the Rhône. His face, the skin of which was indented by exposure to sun and wind, owed its expression almost entirely to his small, light gray eyes, which were surrounded by tiny wrinkles, and which he was perpetually blinking; this gave him an air of roguishness, harsh at times and at others friendly. His mouth, which might have given indications of character that could not be read in his eyes, was entirely hidden by his drooping mustache, beneath which was thrust the stem of a short black pipe, smelling of a mixture of tobacco and of dried grapeskins, which he chewed at rather than smoked. Thin and gaunt, with long, straight legs, and a slight paunch which was more the outcome of lack of exercise than a genuine stoutness, the man gave an impression of a powerful physique. Although carelessly dressed, from his comfortable, well-polished shoes, the good quality of the cloth of his coat, and the collar which he wore with natural ease on a weekday, you guessed that he was respected and well-to-do. His voice and his sparing use of gesture were those of a man accustomed to rule.

His name was Barthélemy Piéchut. He was mayor of the town of Clochemerle, where he was the principal vinegrower, owning the best slopes with southwesterly aspect, those which produce the richest wines. In addition to this, he was president of the agricultural syndicate and a departmental councilor, which made him an important personage over a district of several square miles, at Salles, Odénas, Arbuissons, Vaux and Perréon. He was commonly supposed to have other political aims not yet revealed. People envied him, but his influential position was gratifying to the countryside. On his head he wore only the peasant’s felt hat, tilted back, with the crown dented inwards and the wide brim trimmed with braid. His hands clutched the inside of his waistcoat and his head was bent forward. This was his customary attitude when deciding difficult questions, and much impressed the inhabitants. “He’s thinking hard, old Piéchut!” they would say.

His interlocutor, on the other hand, was a puny individual, whose age it would have been impossible to guess. His goatee beard concealed a notably receding chin, while over an imposing cartilage serving as an armored protection for a pair of resonant tubes which imparted a nasal intonation to all his remarks, he wore old-fashioned spectacles with unplated frames, kept in place by a small chain attached to his ear. Behind these glasses, which his short sight demanded, the glint of his sea-green eyes was of the kind that denotes a mind given over to wild fancies and occupied in dreaming of the ways and means to an unattainable ideal. His bony head was adorned with a Panama hat, which, as the result of exposure to the sun for several summers and storage in a cupboard in winter, had acquired the tint and the crackly nature of those sheaves of Indian corn which, hanging to dry, are a common sight in the Bresse country under the projecting roofs of the farms. His shoes, on which the exercise of the shoemaker’s skill was only too conspicuous, were reaching the period of their final resoling, for it was becoming unlikely that a new piece would rescue the uppers, now definitely breathing their last. The man was sucking at a very meager cigarette, richer in paper than tobacco, and clumsily rolled. This other personage was Ernest Tafardel, schoolmaster, town clerk, and consequently right-hand man to Barthélemy Piéchut, his confidant at certain seasons, but to a limited extent only (for the mayor never went far in his confidences, and never farther than he had decided to go); and lastly, his adviser in the case of administrative correspondence of a complicated nature.

For the smaller details of material existence, the schoolmaster displayed the lofty detachment of the true intellectual. “A fine intelligence,” he would say, “can dispense with polished shoes.” By this metaphor he intended to convey that splendor in dress, or mediocrity, can neither add to nor detract from a man’s intelligence. And further, that at Clochemerle there was to be found at least one fine intelligence—unhappily confined to a subordinate rôle—the possessor of which could be recognized by shabby shoes. For Ernest Tafardel was vain enough to regard himself as a profound thinker, a sort of rustic philosopher, ascetic and misunderstood. Every utterance of his had a pedagogic, sententious twist, and was punctuated at frequent intervals by the gesture which, in pictures that used to be sold to the populace, was assigned to members of the teaching body—a forefinger held vertically above the closed fist raised to the level of the face. Whenever he made a statement, Ernest Tafardel would press his forefinger to his nose with such force as to displace the point of it. It was, therefore, hardly surprising that after twenty years of a profession in which affirmative statements are constantly required, his nose had become slightly deflected to the left. To complete this portrait, it must be added that the schoolmaster’s fine maxims were spoiled by the quality of his breath, with the result that the people of Clochemerle fought shy of his wise utterances at too close quarters. As he was the only person throughout the countryside to be unconscious of this unpleasant defect, the haste with which the inhabitants of Clochemerle would flee from him, and above all their eagerness to cut short every confidential conversation or impassioned dispute, was attributed by him to ignorance and base materialism on their part. When people simply gave way to him and fled without further argument, Tafardel suspected them of despising him. Thus his feeling of persecution rested upon a misunderstanding. Nevertheless, it caused him real suffering, for, being naturally prolix, as a well-informed man he would have liked to make a display of his learning. He concluded from this isolation of his that the race of mountain winegrowers had, as the result of fifteen centuries of religious and feudal oppression, grown addlepated. He revenged himself by the keen hatred he bore towards Ponosse, the parish priest—a hatred which, however, was platonic and based on purely doctrinal grounds.

A follower of Epictetus and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the schoolmaster led a blameless life, devoting his whole leisure to municipal correspondence and to drawing up statements which he sent to the Vintners’ Gazette of Belleville-sur-Saone. Though he had lost his wife many years previously, his morals remained above suspicion. A native of Lozère, a district noted for its austenity, Tafardel had been unable to accustom himself to the coarse jesting of winebibbers. These barbarians, he thought, were flouting science and progress in his own person. For these reasons he felt the more gratitude and devotion to Barthélemy Piéchut, whose attitude towards him was one of sympathy and trust.

But the mayor was a clever fellow, who knew how to turn everything and everybody to good account. Whenever he was to have a serious conversation with the schoolmaster, he would take him out for a walk; by this means, he always got him in profile. It must also be remembered that the distance which separates a schoolmaster from a large landed proprietor placed between them a trench, dug by deference, which put the mayor beyond reach of those emanations which Tafardel bestowed so freely when directly facing people of lesser importance. Lastly, like the good politician that he was, Piéchut turned to his own advantage his secretary’s pestiferous exhalations. If, in some troublesome matter, he wished to obtain the approval of certain municipal councilors of the opposition, the notary Girodot, or the wine-growers Lamolire and Maniguant, he pretended to be indisposed and sent Tafardel, with his papers and his odorous eloquence, to their respective houses. To close the schoolmaster’s mouth, they gave their consent.

The unfortunate Tafardel imagined himself endowed with quite exceptional powers of argument—a conviction which consoled him for his social setbacks, which he attributed to the envy aroused in the hearts of mediocre persons by contact with superior ability. It was a very proud man that returned from these missions. Barthélemy Piéchut smiled unobtrusively and rubbing the red nape of his neck, a sign with him either of deep reflection or of great joy, he would say to the schoolmaster:

“You would have made a fine diplomat, Tafardel. You’ve only to open your mouth and everyone agrees with you.”

“Monsieur le Maire,” Tafardel would reply, “that is the advantage of learning. There is a way of putting a case which is beyond the capacity of the ignorant, but which always succeeds in winning them over.”

At the moment when this history opens, Barthélemy Piéchut was making this pronouncement:

“We must think of something, Tafardel, which will be a shining example of the superiority of a progressive town council.”

“I entirely agree with you, Monsieur Piéchut. But I must point out that there is already the war memorial.”

“There will soon be one in every town, whatever sort of council it may have. We must find something more original, more in keeping with the party program. Don’t you agree?”

“Of course, of course, Monsieur Piéchut. We have got to bring progress into the country districts and wage war unceasingly on obscurantism. That is the great task for all us men of the Left.”

They ceased speaking and made their way across the square, a distance of about eighty yards, halting where it ended in a terrace and commanded a view over the first valley. Behind lay a confused mass of other valleys formed by the slopes of rounded hills that fell away to the level of the plain of the Saone, which could be seen in a blue haze in the far distance. The heat of that month of October gave more body to the odor of new wine that floated over the whole countryside. The mayor asked:

“Have you an idea, Tafardel?”

“Well, Monsieur Piéchut . . . there is a matter that occurred to me the other day. I was intending to speak to you about it. The cemetery belongs, I take it, to the town? It is, in fact, a public monument?”

“Certainly, Tafardel.”

“In that case, why is it the only public monument in Clochemerle which does not bear the Republican motto—‘Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity’? Is that not an oversight which plays into the hands of the reactionaries and the curé? Does it not look like an admission on the part of the Republic that its supervision comes to an end at the threshold of eternity? Does it not amount to a confession that the dead escape from the jurisdiction of the parties of the Left? The strength of priests, Monsieur Piéchut, lies in their monopoly of the dead. It is of the greatest importance to show that we, too, hold rights over them.”

These words were followed by a momentous silence, devoted to an examination of this suggestion. Then the mayor replied, in a brisk, friendly tone:

“Do you want to know what I think, Tafardel? The dead are the dead. Let us leave them in peace.”

“There is no question of disturbing them, but only of protecting them against the abuses of reaction. For after all, the separation of Church and State—”

“It’s no use, Tafardel! No. We should only be saddling ourselves with a troublesome business that interests nobody, and would have a bad effect. You can’t stop the curé from going into the cemetery, can you? Or from doing it more often than other people? And then the dead, Tafardel—they belong to the past. It is the future that we have to think of. It’s some plan for the future that I am asking you for.”

“In that case, Monsieur Piéchut, I return to my proposal for a municipal library, where we should have a choice of books capable of enlarging the people’s minds and of dealing a final blow at past fanaticisms.”

“Don’t let us waste our time over this library business. I have already told you—the people of Clochemerle won’t read those books of yours. The newspaper is ample for their needs. Do you suppose that I read much? Your scheme would give us a great deal of trouble without doing us much good. What we need is something that will make a greater effect, and be in keeping with a time of progress like the present. Then you can think of absolutely nothing?”

“I shall give my mind to it, Monsieur le Maire. Should I be indiscreet in asking whether you yourself—”

“Yes, Tafardel, I have an idea. I’ve been thinking it over for a long time.”

“Ah, good, good!” the schoolmaster replied.

But he asked no question. For there is nothing else which destroys so effectively, in a native of Clochemerle, all inclination to speak. Tafardel did not even betray any curiosity. He contented himself with merely showing confident approval:

“If you have an idea, there is no need to inquire any further!”

Thereupon Barthélemy Piéchut halted in the middle of the square, near the lime tree, while he glanced towards the main street in order to make sure that no one was coming in their direction. Then he placed his hand on the nape of his neck and moved it upwards until his hat became tilted forward over his eyes. There he remained, staring at the ground, and gently rubbing the back of his head. Finally, he made up his mind:

“I am going to tell you what my idea is, Tafardel. I want to put up a building at the town’s expense.”

“At the town’s expense?” the schoolmaster repeated in astonishment, knowing what a source of unpopularity a raid on the common fund derived from taxes can be.

But he made no inquiry as to the kind of building, nor what sum would have to be spent. He knew the mayor for a man of great common sense, cautious, and very shrewd. And it was the mayor himself who, of his own accord, proceeded to clear the matter up:

“Yes, a building—and a useful one, too, from the point of view of the public health as well as public morals. Now let us see if you are clever, Tafardel. Have a guess. . . .”

Ernest Tafardel moved his arms in a gesture indicating how vast was the sphere of conjecture, and that it would be folly to embark on it. Piéchut gave a final tilt to his hat, which threw his face completely into shadow, blinked his eyes—the right one a little more than the left—to get a clear conception of the impression that his idea would make on his hearer, and then laid the whole matter bare:

“I want to build a urinal, Tafardel.”

“A urinal?” the schoolmaster cried out, startled and impressed. The matter, he saw at once, was obviously of extreme importance.

“Yes, a public convenience,” said the mayor.

Now when a matter of such consequence is revealed to you suddenly and without warning, you cannot produce a ready-made opinion regarding it. And at Clochemerle, precipitancy detracts from the value of a judgment. As though for the purpose of seeing clearly into his own mind, with a lively jerk Tafardel unsaddled his large equine nose and held his spectacles to his mouth, where he imbued them with fetid moisture, and then, rubbing them with his handkerchief, gave them a new transparence. Having assured himself that no further specks of dust remained on the glasses, he replaced them with a solemnity that denoted the exceptional importance of the interview. These precautions delighted Piéchut; they showed him that his confidences were producing an effect on his hearer. Twice or thrice more there came a Hum! from Tafardel from behind his thin, ink-stained hand, while he stroked his old nanny-goat beard. Then he said:

“A really fine idea, Monsieur le Maire! An idea worthy of a good Republican, and altogether in keeping with the spirit of the party. Equalitarian in every sense, and hygienic, too, as you so justly pointed out. And when one thinks that the great nobles under Louis the Fourteenth used to relieve themselves on the palace staircases! A fine thing to happen in the times of the monarchy, you may well say! A urinal, and one of Ponosse’s processions—from the point of view of public welfare you simply could not compare them.”

“And how about Girodot,” the mayor asked, “and Lamolire, and Maniguant, the whole gang in fact—do you think they will be bowled over?”

Thereupon was heard the little grating noise that was the schoolmaster’s substitute for laughter; it was a rare manifestation with this sad, misunderstood personage whose joy in life was so tainted, and was reserved exclusively for good objects and great occasions, the winning of victories over the distressing obscurantism with which the French countryside is even now infected. And such victories are rare.

“No doubt of it, no doubt of it, Monsieur Piéchut. Your plan will do them an immense amount of damage in the eyes of the public.”

“And what of Saint-Choul? And Baroness Courtebiche?”

“It may well be the deathblow to the little that remains of the prestige of the nobility! It will be a splendid democratic victory, a fresh affirmation of immortal principles. Have you spoken of it to the Committee?”

“Not yet . . . there are jealousies there. . . . I am rather counting on your eloquence, Tafardel, to explain the matter and carry it through. You’re such an expert at shutting up bellyachers!”

“You may rely on me, Monsieur le Maire.”

“Well, then, that’s settled. We will choose a day. For the moment, not a word! I think we are going to have an amusing time!”

“I think so, too, Monsieur Piéchut!”

In his contentment, the mayor kept turning his hat around on his head in every direction. Still greedy for compliments, to extract fresh ones he made little exclamations to the schoolmaster, such as “Well?” “Now just tell me!” in the sly, cunning manner of the peasant, while he continually rubbed the nape of his neck, which appeared to be the seat of his mental activity. Each exclamation was answered by Tafardel with some fresh eulogy.

It was the loveliest moment of the day, an autumn evening of rare beauty. The air was filled with the shrill cries of birds returning to roost, while an all-pervading calm was shed upon the earth from the heavens above, where a tender blue was gently turning to the rose-pink which heralds a splendid twilight. The sun was disappearing behind the mountains of Azergues, and its light now fell only upon a few peaks which still emerged from the surrounding ocean of gentle calm and rural peace, and upon scattered points in the crowded plain of the Saone, where its last rays formed pools of light. The harvest had been a good one, the wine promised to be of excellent quality. There was cause for rejoicing in that corner of Beaujolais. Clochemerle re-echoed with the noise of the shifting of casks. Puffs of cool air from the stillrooms, bearing a slightly acid smell, cut across the warm atmosphere of the square when the chestnuts were rustling in the northeasterly breeze. Everywhere stains from the wine press were to be seen and already the brandy was in the process of being distilled.

Standing at the edge of the terrace, the two men were gazing at the peaceful decline of day. This apotheosis of the dying summer season appeared to them in the light of a happy omen. Suddenly, with a touch of pomposity, Tafardel asked:

“By the way, Monsieur le Maire, where are we going to place our little edifice? Have you thought of that?”

A rich smile, in which every wrinkle on his face was involved, overspread the mayor’s countenance. All the same his jovial expression was somehow menacing. It was a smile that afforded an admirable illustration of the famous political maxim—“To govern is to foresee.” In that smile of Barthélemy Piéchut’s could be read the satisfaction he felt in his consciousness of power, in the fear he inspired, and in his ownership of lovely sun-warmed vineyards and of cellars which housed the best of the wines grown on the slopes that lay between the mountain passes of the west and the low ground of Brouilly. With this smile, the natural accompaniment of a successful life, he enveloped the excitable, highly strung Tafardel—a poor devil who had not a patch of ground or a strip of vineyard to his name—with the pity felt by men of action for poor feeble scribblers who waste their time over vaporous nonsense.

“Come and let us see the place, Tafardel!” he said simply, making his way towards the main street.

A great utterance. The utterance of a man who has made every decision in advance. An utterance comparable with Napoleon’s when crossing the fields of Austerlitz: “Here, I shall give battle.”