AN OBSERVATION. ACCORDING to certain capable historians of manners and customs the earliest names which appeared in France round about the eleventh century had their origin in some physical or moral peculiarity of the individual, and, more frequently still, were suggested by his trade. This theory would be confirmed by the names which we find at Clochemerle. In 1922, the baker’s name was Farinard, the tailor’s Futaine, the butcher’s Frissure, the pork butcher’s Lardon, the wheelwright’s Bafère, the carpenter’s Billebois, and the cooper’s Boitavin. These names are evidence of the strength of tradition at Clochemerle, and show that the different trades have been handed down from father to son in the same families for several centuries. Such remarkable persistence implies a good dose of stubbornness and a tenacious habit of pursuing both good and evil to their final extremity.

A second observation. Nearly all the well-to-do inhabitants of Clochemerle are to be found in the upper portion of the town, above the church. To say of anyone at Clochemerle, “he’s a lower-town man,” implies that he is in humble circumstances. “A lower Clochemerlian,” or, more curtly still, “bottom of the hill,” is a form of insult. As may be expected, it is in the higher portion of the town that Barthélemy Piéchut, Poilphard, the chemist, and Mouraille, the doctor, live. A little consideration will make this clear. Exactly the same thing happened at Clochemerle as takes place in large cities which are in process of extension. The bolder spirits, of acquisitive disposition, made for the vacant spaces where they could exploit their newly made fortunes, while the more timorous people, doomed to stagnation, continued to herd together in the dwellings which already existed and made no effort to extend the area in which they lived. For these reasons the upper town, between the church and the big turning, is the home of the powerful and the strong.

Lastly. Apart from the tradespeople, the artisans, the town officials, the police commanded by the noncommissioned officer Cudoine, and about thirty ne’er-do-wells employed for the more unsavory jobs, all the inhabitants are vinegrowers, the majority themselves proprietors or descendants of dispossessed proprietors, these latter working on behalf of Baroness Courtebiche, the notary Girodot, and a few landowners in the neighborhood of Clochemerle. Thus it is that the inhabitants of Clochemerle are a proud people, not easily deceived, with a taste for independence.

Before leaving the church, we must say a few words on the subject of the Curé Ponosse, whom we shall note as being to a certain extent the cause of the troubles at Clochemerle—unintentionally, it is true; for this priest, with his peaceful disposition, and at an age when his ministry is carried on as though he were already in retirement, shuns more than ever those contests which are gall and wormwood to the soul and a questionable sacrifice to the glory of God.

Thirty years ago, when the Curé Ponosse took up his abode in the town of Clochemerle, he had come from a somewhat unpleasant parish in the Ardèche. His period of probation as an assistant priest had done nothing to educate him in the ways of the world. He was conscious of his peasant origin, and still retained the blushing awkwardness of a seminarist at odds with the humiliating discomforts of puberty. The confessions of the women of Clochemerle, a place where the men are not inactive, brought him revelations which filled him with embarrassment. As his personal experience in these matters was of short duration, by clumsily conceived questions he embarked on a course of study in carnal iniquity. The horrid visions which he retained as the result of these interviews made his times of solitude, when he was haunted by lewd and satanic pictures, a heavy burden. The full-blooded temperament of Augustin Ponosse was by no means conducive to the mysticism prevalent among those who are racked by mental suffering, which itself usually accompanies physical ill health. On the contrary, all his bodily functions were in splendid order; he had an excellent appetite; and his constitution made calls upon him which his clerical garb modestly, if incompletely, concealed.

On his arrival at Clochemerle in all the vigor of youth, to take the place of a priest who had been carried off at the age of forty-two by an attack of influenza followed by a chill, Augustin Ponosse had the good fortune to find at the presbytery Honorine, an ideal specimen of a curé’s servant. She shed many tears for her late master—evidence this of a respectable and reverent attachment to him. But the vigorous and good-natured appearance of the new arrival seemed to bring her speedy consolation. Honorine was an old maid for whom the good administration of a priest’s home held no secrets, an experienced housekeeper who made ruthless inspections of her master’s clothes and reproached him for the unworthy state of his linen: “You poor wretched man,” she said, “they did look after you badly!” She recommended him to wear short drawers and alpaca trousers in summer, as these prevent excessive perspiration beneath the cassock, made him buy flannel underclothing, and told him how to make himself comfortable with very few clothes when he stayed at home.

The Curé Ponosse enjoyed this soothing kindliness, this watchful care, and rendered thanks to Heaven. But he felt sad, tormented by hallucinations which left him no peace and against which he fought like St. Anthony in the desert. It was not long before Honorine began to realize the cause of these torments. It was she who first alluded to it, one evening when the Curé Ponosse, having finished his meal, was gloomily filling his pipe.

“Poor young man,” she said, “you must find it very hard at your age, always being alone. It’s not human, that sort of thing. After all, you are a man!”

“Oh dear, oh dear, Honorine!” the Curé Ponosse answered with a sigh, turning crimson, and suddenly attacked by guilty inclinations.

“It’ll end by driving you silly, you may depend on it! There have been people who’ve gone off their heads from that.”

“In my profession, one must mortify oneself, Honorine!” the unhappy man replied, feebly.

But the faithful servant treated him like an unruly child:

“You’re not going to ruin your health, are you? And what use will it be to God if you get a bad illness?”

With eyes cast down, the Curé Ponosse made a vague gesture implying that the question was beyond him, and that if he must go mad from excess of chastity, and such were God’s will, he would resign himself accordingly. That is, if his strength held out, which was doubtful. Thereupon Honorine drew nearer to him and said in an encouraging tone:

“Me and the other poor gentleman—such a saintly man he was, too—we fixed it up together. . . .”

This announcement brought peace and balm to the heart of the Curé Ponosse. Slightly raising his eyes, he looked discreetly at Honorine, with completely new ideas in his mind. The servant was indeed far from beautiful, but nevertheless she bore—though reduced to their simplest expression and consequently but little suggestive—the hospitable feminine protuberances. Dismal though these bodily oases might be, their surroundings unflowered and bleak, they were none the less oases of salvation, placed there by Providence in the burning desert in which the Curé Ponosse felt as though he were on the point of losing his reason. A flash of enlightenment came to him. Was it not a seemly act, an act of humility, to yield, seeing that a priest of great experience, mourned by the whole of Clochemerle, had shown him the way? He had only to abandon false pride and follow in the footsteps of that saintly man. And this was made all the easier by the fact that Honorine’s rugged form made it possible to concede to Nature only a necessary minimum, without taking any real delight in such frolics or lingering over those insidious joys wherein lies the gravity of the sin.

The Curé Ponosse, having mechanically uttered a prayer of thanksgiving, allowed himself to be led away by his servant, who took pity on her young master’s shyness. Rapidly and in complete obscurity came the climax, while the Curé Ponosse kept his thoughts far, far away, deploring and bewailing what he did. But he spent later so peaceful a night, and awoke so alert and cheerful, that he felt convinced that it would be a good thing to have occasional recourse to this expedient—even in the interests of his ministry. As regards frequency, he decided to adhere to the procedure laid down by his predecessor; and in this, Honorine would be able to instruct him.

However, be that as it might, sinning he undoubtedly was, and confession became a necessity. Happily, after making inquiries, he learned that at the village of Valsonnas, twenty kilometers distant, lived the Abbé Jouffe, an old theological college chum of his. The Curé Ponosse felt that it would be better to make confession of his delinquencies to a genuine friend. On the following day, therefore, he tucked the end of his cassock into his belt and mounted his priest’s bicycle (a legacy from the departed) and by a hilly route, and with much labor, he reached Valsonnas.

For some little time the two priests were entirely absorbed by their pleasure at meeting again. But the Curé of Clochemerle could not indefinitely postpone his confession of the object of his visit. Covered with confusion, he told his colleague how he had been treating Honorine. Having given him absolution, the Abbé Jouffe informed him that he himself had been behaving in a similar manner towards his servant, Josépha, for several years past. The visitor then remembered that the door had, in fact, been opened by a dark-haired person who, though she squinted, had a nice, fresh appearance and a pleasant sort of dumpiness. He felt that his friend Jouffe had done better than himself in that respect, for, so far as his own taste was concerned, he could have wished that Honorine were less skimpy. (When Satan sent him voluptuous visions, it was always in the form of ladies with milk-white skins, of liberal charms, and limbs of splendidly generous proportions.) But he banished this envious thought, stained as it was with concupiscence and lacking in charity, in order to listen to what Jouffe was explaining to him. This is what he was saying:

“My dear Ponosse, as we cannot entirely detach ourselves from matter, a favor which has been granted only to certain saints, it is fortunate that we both have in our own homes the means of making an indispensable concession to it secretly, without causing scandal or disturbing the peace of souls. Let us rejoice in the fact that our troubles do no injury to the Church’s good name.”

“Yes,” answered Ponosse, “and moreover, is it not useful that we should have some competency in all matters, seeing that we are often called upon to give decisions and advice?”

“Indeed I think so, my good friend, to judge by cases of conscience that have been laid before me here. It is certain that without personal experience I should have stumbled over them. The sixth commandment is the occasion of much disputation and strife. If our knowledge on this point were not, I will not say profound, at least sufficient, we should find ourselves directing some of the souls under our care into a wrong path. Between ourselves, we can say this—complete continence warps judgment.”

“It strangles the intelligence!” said Ponosse, remembering his sufferings.

As they drank the wine of Valsonnas, which is inferior to that of Clochemerle (in this respect Ponosse was better off than Jouffe), the two priests felt that an unforeseen similarity in their respective problems could only strengthen the bonds of a friendship which dated from their early youth. They then decided upon certain convenient arrangements, as, for example, to make their confessions to each other in future. In order to spare themselves numerous and fatiguing journeys, they agreed to synchronize their carnal lapses. They allowed themselves, as a general principle, the Monday and Tuesday of each week, as being unoccupied days following the long Sunday services, and chose the Thursday for their confessions. They agreed further to take equal shares in the trouble involved. One week the Abbé Jouffe was to come to Clochemerle to make his own confession and receive that of Ponosse, and the following week it would be the Curé Ponosse’s turn to visit his friend Jouffe at Valsonnas for the purpose of their mutual confession and absolution.

These ingenious arrangements proved completely satisfactory for a period of twenty-three years. Their restricted employment of Honorine and Josépha, together with a fortnightly ride of forty kilometers, kept the two priests in excellent health, and this in turn procured them a breadth of view and a spirit of charity which had the very best effects, at Clochemerle as at Valsonnas. Throughout this long period there was no accident of any kind.

It was in 1897, in the course of a very severe winter. One Thursday morning the Curé Ponosse awoke with the firm intention of making the journey to Valsonnas to obtain his absolution. Unfortunately there had been a heavy fall of snow during the night, which made the roads impassable. The Curé of Clochemerle was anxious to start off in spite of this, and refused to listen to his servant’s crier and reproaches; he considered himself to be in a state of mortal sin, having taken undue advantage of Honorine for some days past as the result of idleness during the long winter evenings. In spite of his courage and two falls, the Curé Ponosse could not cover more than four kilometers. He returned on foot, painfully, and reached home with chattering teeth. Honorine had to put him to bed and make him perspire. The wretched man became delirious on account of his mortal sin, a condition in which he felt it impossible to remain. In the meantime the Abbé Jouffe, looking out in vain for Ponosse, was in a state of deadly anxiety. He had High Mass the following day and was wondering whether he would be able to celebrate it. Happily, the Abbé of Valsonnas was a man of resource. He sent Josépha to the post with a reply-paid telegram addressed to Ponosse: Same as usual. Miserere mei by return. Jouffe. The Curé of Clochemerle replied immediately: Absolvo te. Five paters five aves. Same as usual plus three. Deep repentance. Miserere urgent. Ponosse. The absolution reached him by telegram five hours later, with “one rosary” as a penance.

The two priests were so delighted with this expeditious device that they considered the possibility of using it constantly. But a scruple held them back: it meant giving too much facility for sin. Further, the dogma of confession, down to its smallest details, goes back to a time when the invention of the telegraph was not even a matter of conjecture. The use they had just made of it raised a point of canon law which would have needed elucidation by an assembly of theologians. They feared heresy, and decided to use the telegraph only in cases of absolute necessity, which arose on three occasions in all.

Twenty-three years after Ponosse’s first visit to his friend, the Abbé Jouffe had the misfortune to lose Josépha, then sixty-two years of age. She had kept herself until the end in a good state of bodily preservation, even though her stoutness had increased her weight to over twelve stone, a great one for a person whose height did not exceed five feet two inches. The necessity of dragging about this massive frame had caused her legs to swell, and the growth of fat over her heart prevented that organ from functioning freely. She died of a species of angina pectoris. The Abbé Jouffe did not replace her. To mold a new servant to his habits appeared to him a task beyond his strength. Arrival at an age well past fifty brought peace and calm in its train. He contented himself with a charwoman who came to tidy up the vicarage and prepare his midday meal. In the evening some soup and a piece of cheese were all that he needed. No longer requiring absolution for sins that were hard to confess, he refrained from coming to Clochemerle. This abstention brought disorder into the life of the Curé Ponosse.

Ponosse was now approaching the age of fifty. For a long time past he could quite comfortably have dispensed with Honorine. The faithful servant had reached an age when she might well have retired from service. Unlike Josépha, she had grown continually leaner until she was as thin as a rake. But the Curé Ponosse, always a shy man, was afraid of offending the poor woman by putting an end to relations which he no longer felt to be an overmastering necessity. The example given him by Jouffe decided him. And there was this too—that the journey to Valsonnas was a prolonged agony for the Curé of Clochemerle, who had become very stout and suffered from emphysema. He had to dismount at the bottom of each hill, and the descents made him giddy. So long as his colleague returned his visits he did not lose heart. But when he saw himself condemned to bear alone the burden of all those journeys, he said to himself that the remnants of a former Honorine were not worth all those hours of superhuman effort. He told his servant of his difficulties. She took it very badly, and thought that she had been insulted; which was what the Curé Ponosse had feared. She hissed at him:

“I suppose you’ll be wanting young girls now, Monsieur Augustin?”

She called him “Monsieur Augustin” in times of crises. Ponosse set out to calm her.

“As for young girls,” he said, “Solomon and David needed them. But the matter is a simpler one for me. I need nothing more, my good Honorine. After all, we are now of an age to lead peaceful lives, to live, in fact, without sin.”

“Speak for yourself,” Honorine retorted sharply; “I’ve never sinned.”

In the mind of the faithful servant, that was the truth. She had always considered as a kind of sacrament anything that her curés had thought fit to administer to her. She continued in a tyrannical tone of voice that made the good priest tremble:

“Do you think I did that because I was a wicked woman, like some low creatures I know at Clochemerle might have done? Like the Putet kind of women with their nasty hanging around? You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Monsieur Augustin, and I don’t mind telling you so even if I am a poor nobody. I did it for your health . . . for your health, you understand, Monsieur Augustin?”

“Yes, I know, my good Honorine,” the curé answered, falteringly. “Heaven will reward you for it.”

For the Curé of Clochemerle that day was a difficult one, and it was followed by weeks during which he lived in a state of persecution and surrounded by suspicion. At last, when she had become satisfied that her privilege was not being taken from her in order to be bestowed elsewhere, Honorine grew calm. In 1923 the relations between the Curé of Clochemerle and his servant had been irreproachable for a period of ten years.

Every age makes its own demands, has its own joys. For the past ten years, the Curé Ponosse had found solace in his pipe, and above all in wine, the excellent wine of Clochemerle, which he had learned how to use to advantage. This knowledge had gradually come to serve as a reward for his apostolic devotion. Let us explain.

On his arrival at Clochemerle thirty years before, the young priest Augustin Ponosse found a church well attended by women, but with rare exceptions deserted by men. Burning with youthful zeal, and very anxious to please the Archbishop, the new priest, thinking to improve on his predecessor (that eternal presumption of youth), began a campaign of recruitment and conversion. But he soon realized that he would have no influence over the men so long as he was not a good judge of wine, that being the overwhelming interest at Clochemerle. There the delicacy of the palate is the test of intelligence. A man who, after three gulps and turning the wine several times round in his mouth, cannot say whether it is Brouilly, Fleurie, Morgon, or Juliénas, is looked upon by these ardent winegrowers as an imbecile. Augustin Ponosse was no judge of wine at all. He had drunk nothing all his life but the unspeakable concoctions of the seminary, or else, in Ardèche, very thin, inferior wine which you would swallow without noticing it. For some time after his arrival, the strength and richness of the Beaujolais wine completely overcame him. It was neither a gentle potion suggesting a baptismal font, nor a soft drink for dyspeptic sermonmongers.

The sentiment of duty sustained the Curé Ponosse. Defeated so far as actual competence was concerned, he swore that his drinking capacity should astonish the natives of Clochemerle. Filled with the fervor of the evangelist, he became a frequent visitor at the Torbayon Inn, where he hobnobbed with all and sundry, capping their stories with others of his own; and there were often spicy ones about the behavior of the priestly fraternity.

The Curé Ponosse took it all in good part, and Torbayon’s customers never ceased filling his glass. They had made a vow to see him take his departure some day “completely bottled.” But Ponosse’s guardian angel watched over him so that he might retain a spark of decent sanity and a deportment consistent with ecclesiastical dignity. This guardian angel was assisted in his task by Honorine who, whenever she had missed her master for some time, left the presbytery, which was just opposite, crossed the street, and planted herself at the entrance to the inn, a stern figure suggestive of Remorse.

“Monsieur le Curé,” she would say, “you are wanted at the church. Come along now!” Ponosse would finish his drink and get up immediately. Letting him go ahead, Honorine then closed the door, casting a look of thunder at the loafers and tipplers who were corrupting her master and taking advantage of his credulous and gentle nature.

These methods did not win over a single soul to God. But Ponosse acquired a genuine competence in the matter of wines, and thus won the esteem of the vinegrowers of Clochemerle, who spoke of him as a man who didn’t give himself airs, was not a half-baked sermonizer, and was always ready for a good honest drink. Within the space of fifteen years Ponosse’s nose blossomed superbly; it became a real Beaujolais nose, huge, with a tint that hovered between the Canon’s violet and the Cardinal’s purple. It was a nose that inspired the whole region with confidence.

No one can acquire competence in anything unless he has a taste for it, and taste induces need. This is exactly what happened to Ponosse. His daily consumption reached about three and a half pints, deprivation of which would have caused him suffering. This large quantity of wine never affected his head, but it kept him in a state of somewhat artificial beatitude which became more and more necessary to him for the endurance of the vexations of his ministry, to which were added domestic worries caused by Honorine.

Advancing years had greatly altered the servant. And this is a curious fact—at the time when the Curé Ponosse was leading a strictly celibate life, Honorine no longer gave him the same attention and respect, and her feelings of piety appeared suddenly to leave her. Instead of saying her prayers she took to snuff, which seemed to procure her a deeper satisfaction. A little later on, taking advantage of reserves of old bottles of wine, a priceless possession resulting from gifts of the faithful, which had accumulated in the cellar, she began helping herself, and helping herself with such entire lack of discrimination that she might sometimes be found tippling out of her own pans. She became cross-grained and peevish, her work was neglected, and her sight deteriorated. In the solitude of her kitchen, whither Ponosse no longer ventured, she gave vent to strange mutterings with a vague menace about them. The priest’s cassocks were spotted, his linen lacked buttons, his bands were badly ironed. He lived in a state of fear. If in the past Honorinc had given him satisfaction and served him well, it is certain that in later life she caused him great trouble and vexation. That the precious flavor of a rare vintage should have become more than ever an indispensable consolation for the Curé of Clochemerle will be easily understood.

Other forms of consolation, too, he found through the medium of Baroness Courtebiche, after she took up permanent residence at Clochemerle in 1917. At least twice each month he dined at the château, at the Baroness’ table, where the consideration shown to him was given less on personal grounds than on account of the institution of which he was merely a rustic representative (“rather an oaf,” the great lady used to say of him behind his back). But he was unconscious of this subtle distinction, and attentions bestowed on him with a brusqueness due to a lordly desire to keep everyone in his right place nevertheless entirely won his heart.

In his declining years, and at a time when he no longer looked for any new source of pleasure, he enjoyed a revelation of all that is implied by the choicest food and drink served by well-trained footmen amidst a gorgeous display of table linen, glass, and emblazoned silver, the use of which embarrassed but also enraptured him. Thus the Curé Ponosse, at about the age of fifty-five, made acquaintance with the pomp and circumstance of that social sphere which he had humbly served by his teaching of the Christian virtue of resignation—a virtue which so favors the growth of great fortunes.

At his first visit to the château, he felt he had a clear intuition of the celestial joys which will in due time be the heritage of the righteous. Unable to conceive of heavenly bliss unless he clothed it with material equivalents borrowed from the realities of this world below, the Curé Ponosse had vaguely imagined that time in Paradise would be spent in perpetually drinking Clochemerle wine and (sin having been abolished) in taking lawful pleasure with fair ladies, whose coloring and figure it would be possible to vary according to one’s taste. (His exclusive—and dull—relations with Honorine had filled him with a great desire for change, and made him interested in fantasy and strange experiences.) These imaginings lay dormant in a corner of his brain which was rarely awake. If he wanted to enjoy them he resorted to a subterfuge. He said to himself, “Supposing I were in Heaven, and that nothing were forbidden.” The sky thereupon became peopled with forms of surpassing sweetness wherein could be recognized detached portions of his prettiest parishioners—in a magnified form brought about by privations extending over a lifetime, and enlarged a hundredfold in a kind of superhuman mirage. Without evil intent, and protected by his mental reservation, he refreshed himself with these imagined pictures. These nebulous beauties procured him a form of bliss that was independent of matter and unrelated to any of his former earthly desires. Thus it was that, as he approached his sixtieth year, he could indulge without danger in these visions of Eden at times when he had exhausted the resources of his breviary. But he did not resort to them too freely, for they left him in a state of depression, and of amazement at the realization of what unsettling aspirations may haunt the recesses of a pious mind.

Since the Curé Ponosse had become one of the Baroness’ regular guests, his idea of Heaven had increased in grandeur. He conceived it as being furnished and decorated ad infinitum in the same manner as the château of the Courtebiche family, the most splendid residence he knew. The joys of eternity remained unaltered, but henceforth they assumed a matchless quality derived from the beauty of the setting, the distinction of the surroundings, and the large staff of mute, angelic servants which ministered to them. As for the fair ladies for recreation, they were no longer of common stock, but marchionesses or princesses, with subtle charms, and skilled in following up the pleasures of witty conversation with seraphic but amorous overtures to the blessed, who in their turn need feel no shame or place restraint on their delights. The fullness of complete self-abandonment was a thing that the Curé Ponosse had never known on earth, held back as he ever was by scruple and by the questionable charm of the object of his affections, who smelled rather of floor polish than of the perfumes of the boudoir.

Such, morally and physically, was the Curé Ponosse in the year 1922. The passage of time had brought him wisdom and calm, and had also decreased his height, which was formerly five feet six inches, but now two and a half inches less. His diameter at the waist, however, had increased twofold. His health was good except for breathlessness, occasional bleeding at the nose, attacks of rheumatism in winter, and (at all times of the year) irritating discomfort in the region of the liver. The worthy man bore these troubles patiently, offering them to God by way of expiation, and entered on a peaceful old age, sheltered by a blameless reputation unclouded by the least breath of scandal.

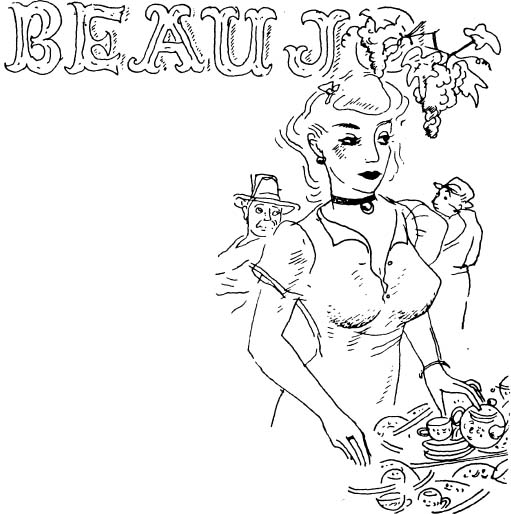

Let us now continue our walk, turning to the right as we come out of the church. The first house we meet, which is at a corner of Monks’ Alley, is the Beaujolais Stores, the principal shop in Clochemerle. Linen drapery, textiles, hats, ready-made clothes, haberdashery, hosiery, grocery, Liqueurs of superior quality, toys, and household utensils are to be found there. Any kind of goods not ordinarily supplied by the other shops in the town is readily available. At that time the attractions of this fine establishment, and its prosperity, were due to a single individual.

Near the entrance of the Beaujolais Stores, Judith Toumignon could be seen and admired, a veritable daughter of fire, with her flamboyant shock of hair, flaming tresses that might have been stolen from the sun. The common herd, impervious to fine distinctions, spoke of her merely as “red-haired,” or spitefully as “ginger.” But there are differences to note. Red hair in women may be lusterless or brick-colored, a dull unattractive red. But Judith Toumignon’s hair was not like that; on the contrary, it was of reddish gold, the tint of mirabelle plums ripened in the sun. This beautiful woman was, in fact, a triumph of blonde beauty, a dazzling apotheosis of the warm tints which constitute the Venetian type. The heavy, glowing turban which adorned her head, only to vanish at the nape of her neck in rapturous sweetness, compelled the gaze of one and all, which lingered over her from head to foot in fascination and delight, finding at all points occasion for extraordinary gratification. The men relished her charm in secret, but could not always hide what they felt from their wives, whose misgivings, profound enough to affect them physically, endowed them with some sort of second sight revealing clearly who the insolent usurper was.

There are times when Nature’s whim, in defiance of circumstances of rank, education, or means, produces a masterpiece. This creation of her sovereign fancy she places where she will. It may be a shepherdess, it may be a circus girl. By these challenges to probability she gives a new and furious impetus to social displacements, and paves the way for new combinations, social graftings, and bargainings between sensual appetite and the desire for gain. Judith Toumignon was an incarnation of one of these masterpieces of Nature, the complete success of which is rarely seen. A perverse and prankish destiny had placed her in the center of the town, where she was engaged in receiving customers at a shop. But a picture of her thus occupied would be incomplete, for her principle role, unseen but profoundly human, was that of inciting to the raptures of love. Though on her own account she was not inactive in this matter, and practiced no niggardly restraint therein, her participation in the sum total of Clochemerle’s embraces should be regarded as trifling in comparison with the function of suggestion that she exercised, and the allegorical position she occupied, throughout the district. This radiant, flaming creature was a torch, a Vestal richly endowed, entrusted by some pagan goddess with the task of keeping alight at Clochemerle the fires of passion.

As applied to Judith Toumignon, the word masterpiece may be used without hesitation. Her face beneath its fascinating fringe was a trifle wide. Its outline was graceful in the extreme, with its firm jaw, the faultless teeth of a woman with good appetite and juicy lips continually moistened by her tongue, and enlivened by a pair of black eyes which still further accentuated its brilliance. One cannot enter into details where her too intoxicating form is concerned. Its lovely curves were so designed that your gaze was held fast until you had taken them all in. It seemed as though Phidias, Raphael, and Rubens had worked together to produce it, with such complete mastery had the modeling of the prominent points been carried out, eschewing scantiness in every way, and dexterously insisting upon amplitude and fullness in such manner as to provide the eyes of desire with conspicuous landmarks on which to rest. Her breasts were two lovely promontories. Wherever one looked, one discovered soft open spaces, alluring estuaries, pleasant glades, hillocks, mounds, where pilgrims could have lingered in prayer. But without a passport—and such was rarely given—this rich territory was forbidden ground. A glance might skim its surface, might detect some shady spot, might linger on some peak. But none might venture farther, none might touch. So milk-white was her flesh, so silky its texture, that at sight of it the men of Clochemerle grew hoarse of speech and were overcome by feelings of recklessness and desperation.

Ruthlessly intent on finding in her some blemish or defect, the women broke tooth and nail on that armor of faultless beauty. It made of Judith Toumignon a being under special protection, whose overflowing kindliness appeared on her lovely lips in calm and generous smiles. It pierced like daggers the flesh of her jealous but uncourted rivals.

The women of Clochemerle—those at least who were still in the running in the race for love—secretly hated Judith Toumignon. This hatred was, however, as ungrateful as it was unjust. There was not one of those discomfited women who, thanks to the darkness which lends itself to such forms of substitution, was not indebted to her for attentions which, deprived of their ideal object, still strove to attain it by such means as were available at the moment.

The Beaujolais Stores were so situated, at the center of the town, that the men of Clochemerle passed by the shop nearly every day. Nearly every day, openly or stealthily, cynically or hypocritically, according to their character, their reputation, or their occupation, they gazed at the Olympian goddess. Seized with hunger at the sight of this sumptuous banquet, they returned home with an increased supply of the courage required for consuming the savorless wish-wash of legitimate repasts. In the nocturnal sky of Clochemerle, her glowing brilliance formed a constellation of Venus, a guiding polestar for poor hapless devils lost in the wilderness with inert and lifeless shrews as their night companions, and for youths athirst in the stifling solitudes of shyness. From the evening angelus till that of morning, all Clochemerle rested, dreamed, and loved under the star of Judith, of that smiling goddess of satisfying caresses and duties well fulfilled, of that dispenser of happy illusions to men of courage and good will. Thanks to this miraculous priestess, no man in Clochemerle was left idle or unemployed. The warmth of this overwhelming creature was felt even by old men asleep. Hiding from them none of the abundant treasures of her lovely form, like generous-hearted Ruth, bending over a quavering and toothless Boaz, she could induce in them still a few slight thrills, which gave them a little joy before they passed into the chill of the tomb.

A still better picture can be given of this lovely daughter of commerce, at the moment when she was at the zenith of her power and splendor. Listen to the account of her given by the rural constable, Cyprien Beausoleil, who has always paid special attention to the women of Clochemerle—for professional reasons, so he says. “When the women keep quiet, everything goes all right. But to get ’em like that, the men have got to keep up to the mark.” Now there arc people who declare that in this respect Beausoleil was a friend in need, sympathetic and understanding, and always ready to lend a helping hand to those men of Clochemerle whose strength had been undermined and whose wives had taken to scolding and had got altogether above themselves. (It should be mentioned that the constable kept secret these little services rendered to his friends.) Let us hear his simple tale:

“That Judith Toumignon, sir, whenever she laughed you could see all inside her mouth—wet it was, too—and all her teeth, not one missing, and her lovely big tongue right in the middle of ’em; it made you feel greedy, it did. Yes, it gave you something to think about. And that wasn’t all, neither. There were things you couldn’t see that—well, they weren’t likely to disappoint you. That confounded woman, sir, I can tell you, she made every man in Clochemerle ill!”

“Ill, Monsieur Beausoleil?”

“Yes, sir, downright ill they were. And for why? Holding themselves back from trying to touch her. Yes, she was just made for it, that woman. I’ve never seen anything like it. The times I’ve called her a bitch to myself—just letting off steam, as you might say, by cursing her, because I couldn’t stop thinking about her. And to stop thinking about her after you’d seen her—well, you just couldn’t. It was more than flesh and blood could stand, all that spread out before you, as though she wasn’t showing you anything at all, with that behind of hers under the tight-fitting stuff of her dress, and her round bosom shoved under your nose, just because her silly fool of a husband was there and you couldn’t even say a nice word to her! Just like a starving man you were, sir, when Judith came near you, and you got a sniff of that lovely soft white skin of hers, and it was a case of hands off, the devil take her!

“The end of it was, I stopped going there. It upset me too much, seeing that woman. I got waves of giddiness, just like that time I nearly had a sunstroke. That was the year of the war when it was so hot. When you get those heat waves, like it happens in dry years, if you have to go out right into the sun you mustn’t drink wine stronger than ten per cent. And that day, at Lamolire’s . . .”

But it is time to return to Judith Toumignon, reigning sovereign of Clochemerle, to whom all the men paid their tribute of desire, and all the women their secret tribute of hate, hoping each day that ulcers and peeling skin might come to disfigure that insolent body of hers.

The most relentless of Judith Toumignon’s calumniators was Justine Putet, her immediate neighbor, chief among Clochemerle’s virtuous women, who overlooked from her window the back premises of the Beaujolais Stores. Of all the different hatreds to which Judith Toumignon was exposed, that of the old maid proved to be the most tenacious and the most effective, being immensely reënforced by her piety, and doubtless also by an incurable virginity which was an added jewel in the Church’s crown. Entrenched within the citadel of her unassailable virtue, this Justine Putet was a rigid censor of the town’s morals, with special reference to those of Judith Toumignon. Judith’s general fascination and her joyful and melodious outbursts of laughter became for Justine a daily insult of the most painful nature. The lovely tradeswoman was happy and showed it—a hard thing to forgive.

The position of official and legitimate owner of the beautiful Judith was held by François Toumignon, her husband. But the actual possessor of her person and her affections was Hippolyte Foncimagne, Clerk to the Justices of the Peace, a tall, dark, handsome fellow. He had a fine head of hair with a slight wave in it, and even during the week he wore cuffs and ties of unusual excellence—for Clochemerle, that is. Being a bachelor, he lodged at the Torbayon Inn.

Guilty though it was, Judith found in this love affair frequent and passionate delight, which proved as beneficial to her complexion as it was to her temper. In this last respect, it was François Toumignon, blissfully ignorant, who reaped the benefit, and who thus unconsciously had his own dishonor to thank for the enviable peace and quiet which he enjoyed at home. In the disorder of human affairs these immoral situations are, alas, only too frequent.

Of obscure origin, Judith had to earn her own living at an early age. For a beautiful girl with all her wits about her this presented no difficulties. At the age of sixteen she left Clochemerle for Villefranche, where she lodged with an aunt, and worked at various jobs in succession, in cafés, hotels, or shops. Wherever she went she made a deep impression and indeed caused such disturbance that most of her employers offered to leave their wives and their businesses and take her, and all the money they possessed, away with them. The offers of these important but deplorably obese gentlemen she haughtily refused, being enamored of love for its own sake, as typified by a handsome young man, and uncontaminated by considerations of money, with which she was physically unable to associate love. Her distaste for them dictated her conduct: passion was what she demanded, not paternal embraces or sentimental nonsense. She was subject to overwhelming impulses, and often preferred to bury in complete oblivion what had been a case of genuine surrender. Every day of her life some new joy was her portion, though it ended always in harrowing distress. At that time she had had some lovers and several passing fancies.

In 1913, at the age of twenty-two, when her beauty was in full bloom, she reappeared in the district and made a general sensation. One in particular of Clochemerle’s inhabitants fell madly in love with her, François Toumignon, the “son of the Beaujolais Stores,” certain to inherit a fine commercial property. He was on the eve of becoming engaged to Adèle Machicourt, another beautiful girl. He left her and began harassing and entreating Judith. She, still under the smart of a disappointment, and smiling perhaps at the idea of getting the young man away from a rival, or wishing maybe to settle down once for all, allowed herself to be married to him. This was an insult that Adèle Machicourt, who ten months later had become Adèle Torbayon, was destined never to forgive. Not that the jilted woman regretted the loss of her first fiancé, for Arthur Torbayon was unquestionably a handsomer man than François Toumignon. But the affront was one of those that a woman who is at all worthy of the name never forgets, and which in the country may occupy the leisure of a whole lifetime.

The proximity of the inn and the Beaujolais Stores, situated as they were on opposite sides of the street, fanned the flame of her resentment. Several times daily, from their doorsteps, these ladies observed each other. Each one eagerly surveyed the other’s beauty in the hope of finding some defect therein. To Adèle’s rancor, contempt on Judith’s part was a necessary reply. During this mutual observation the two women would assume an air of great happiness, very flattering to their husbands.

In the year of Judith’s marriage, Toumignon’s mother having died, she found herself in full possession of the Beaujolais Stores. Having a natural aptitude for commerce, she expanded the business of the shop. She had plenty of time to give to it, being but little concerned with François Toumignon, who had proved deplorably weak in every way. Judith acquired the habit of going once a week either to Villefranche or to Lyons—on business, so she said. The war put the finishing touch to Toumignon’s debility, and made him a drunkard as well.

At the end of the year 1919, Hippolyte Foncimagne appeared at Clochemerle, took up his abode at the inn, and immediately set about taking steps to supply himself with a number of household necessities which the suspicious watchfulness of Arthur Torbayon precluded him from obtaining from his hostess, as it would have been a simple matter for him to do. He visited the Beaujolais Stores to make trifling purchases, and did this so constantly that it became a kind of legend. Proceeding piecemeal, he provided himself with eighteen self-fixing buttons, articles which are very popular among bachelors who have nobody to look after these matters. The eyes of the handsome legal assistant had an Oriental languor about them. They made a lively impression on Judith, and gave her back all the impetuous ardor of her youth, now enriched and re-enforced by the experience that only maturity can bring.

It was soon observed that on Thursdays, the day on which Judith took the motor omnibus to Villefranche, Foncimagne invariably went off on his motor bicycle and was absent for the whole day. It was further noticed that the fair Judith began to make considerable use of her bicycle, for reasons of health according to her own account. But these same reasons always took her along the road which leads directly to Moss Wood, in which the loving couples of Clochemerle are wont to take shelter. It was Justine Putet who disclosed the fact that the young Clerk of the Court was in the habit of creeping into Monks’ Alley at nightfall and entering the little door which opens into the courtyard of the Beaujolais Stores, while Toumignon was still hanging about at the café. Lastly, people declared that they had met Foncimagne and Judith in a certain street in Lyons which is full of hotels. From that time onwards Toumignon’s dishonorable fate left no further room for doubt.

By the year 1922, when this intrigue had been proceeding with shameless openness for three years, all interest in it had come to an end. For a long time past, a scandal, perhaps even a tragedy, had been generally expected. Subsequently, when the guilty couple were seen to be firmly established in their irregular union, with no thought of concealment, they ceased to attract attention. The only person along the entire valley who was ignorant of the whole business was Toumignon himself. He had treated Foncimagne as his greatest friend, and was constantly bringing him to the house, proud to show off Judith to him. This he did to such an extent that she herself thought it necessary to intervene, saying that the young man was seen there too often and that it would end by making people gossip.

“Gossip about who? Gossip about what?” Toumignon asked.

“Me and this Foncimagne. Can’t you see what people will be saying?”

This idea struck Toumignon as being irresistibly funny, but he gave vent to his wrath against the mischievous gossips.

“If ever you catch anyone saying anything wrong, you just send him along to me. You understand? And won’t I give him an earful!”

As luck would have it, just at that moment Foncimagne came in. Toumignon gave him an enthusiastic welcome.

“Listen, Hippolyte, here’s a good yarn. You’re supposed to be carrying on with Judith!”

“I . . . I . . .” Foncimagne stammered out, conscious that he was beginning to blush.

“François, François, come now, don’t talk nonsense!” Judith cried out hastily, blushing too, as though her modesty were offended, and anxious also to correct the misunderstanding.

“Let me finish, for the Lord’s sake!” Toumignon answered. “It isn’t so often you hear a joke in these parts, where most of ’em are fools. Well, it seems people are saying that you play about with Judith. You don’t think that funny?”

“François, shut up!” the unfaithful wife repeated.

But there was no holding him back. He was completely unrestrained.

“Look here, Hippolyte, she’s a beautiful woman, Judith, don’t you think? Very well, then, I tell you she’s not a woman, she’s an icicle! And if ever you can get her to thaw, I’ll stand you any number of drinks! Make yourself at home. I’ve got to go along to Piéchut. Make hay while the sun shines, Hippolyte. Let’s see if you arc cleverer than me.”

After the following final injunction, he closed the shop door behind him.

“When you catch anyone talking, Judith, you send him along to me. Understand?”

Never before had the handsome Clerk of the Court been so ardently beloved by the beautiful daughter of commerce, and this carefree arrangement meant lasting happiness for three different people.