THE CURÉ HAD taken off his chasuble and wearing only his surplice over his cassock, he had just mounted to the pulpit with much difficulty and labor. His first words were “Dear brethren, let us pray.” He began with prayers for the dead and for the benefactors of the parish, and this allowed him to recover his breath. He made special intercession for all the inhabitants of Clochemerle who had died since the famous epidemic of 1431. When the prayers were ended the Curé Ponosse read out the announcements for the week and the banns of marriage. Finally, he read the Gospel for the Sunday, which he was to take as the theme of his address. His address that day had to be of a very special character, and so designed as to make a profound impression; it caused him a certain amount of anxiety. He read out the following passage:

“And when he was come near, he beheld the city, and wept over it, saying, If thou hadst known, even thou, at least in this thy day, the things which belong unto thy peace! but now they are hid from thine eyes. For the days shall come upon thee, that thine enemies shall cast a trench about thee, and keep thee in on every side, and shall lay thee even with the ground, and thy children within thee; and they shall not leave in thee one stone upon another; because thou knewest not the time of thy visitation.”

Then, after a moment of silent prayer, the Curé Ponosse made the sign of the Cross, with a wide gesture, slowly and majestically, in a manner intended to convey an unaccustomed solemnity, together with a suggestion of menace; for it was indeed a tiresome and worrying task that he had undertaken. So keenly did he feel this that the odd stateliness of his sign of the Cross, which he himself believed to be impressive, merely gave him an appearance of being slightly indisposed. He began somewhat as follows:

“You have just heard, my dear brethren, the words spoken by Jesus when He beheld Jerusalem: ‘If thou hadst known, at least in this thy day, the things which belong unto thy peace!’ My dear brethren, let us meditate within ourselves, let us ponder a moment. Would not Jesus, had He wandered in our lovely, fertile Beaujolais and perceived from afar, from the summit of some lofty hill, our splendid town of Clochemerle—would not Jesus have had occasion to speak the same words which the spectacle of a disunited Jerusalem constrained Him to utter? My dear brethren, does peace reign in our midst? Does charity—that love for one’s neighbor which the Son of God had so supremely that He died for us on the Cross?”

It is unnecessary to quote in full Ponosse’s development of his theme. It was not a brilliant performance. Alas, for the space of fully twenty minutes the worthy man was in somewhat of a tangle. This was due to the fact that he was making a new departure. Thirty years previously, with the help of his friend the Abbé Jouffe, he had composed some fifty sermons which should have met all the requirements of a ministry exercised in an atmosphere of calm and peace. Ever since that time, the Curé of Clochemerle had remained content with this pious repertory, which amply fulfilled the spiritual needs of the inhabitants, who would doubtless have been disconcerted by too varied expositions of doctrine. And now suddenly, in 1923, the Curé Ponosse found himself obliged to resort to improvisation in order to slip in some allusions in his sermon to the fateful urinal. These allusions, given out with the authority of the pulpit behind them, and on the very day of the annual festival of the countryside, would rally all the Christian elements in the town to the Church’s defense, and by their sheer unexpectedness would spread confusion and dismay in the ranks of the opposite party, which included people largely indifferent to religion, and others who never went to church, but very few genuine atheists.

Twice already the curé had taken out his watch. His eloquence was becoming more and more entangled in a labyrinth of phrases from which there appeared to be no way out. He had continually to make fresh starts, with many a h’m . . . and an er . . . er . . . and an increasing accumulation of “My dear brethren’s in order to gain time for thought. He must get through with it at all costs. The Curé of Clochemerle offered up a prayer of entreaty to Heaven: “O Lord, grant me courage, give me inspiration!” He flung himself boldly into the breach:

“And Jesus said, as He drove out those who were thronging the temple: ‘My house is the house of prayer: but ye have made it a den of thieves.’ Yes, my dear brethren, we will take Jesus’ firmness as an example for ourselves to follow. We also, we Christians of Clochemerle, shall not shrink from the task of driving out all those who have brought impurity to the very doors of our beloved church! On this monument of infamy, on this accursed slate, let us wield the pickax of deliverance! My brethren, my dear brethren, our watchword shall be—demolition!”

This declaration, so little in the usual manner of the Curé of Clochemerle, was followed by a silence that was almost startling. Then, in the midst of this silence, from the back of the church a drunken voice rang out:

“All right, you just try and knock it down! You’ll see what’ll happen to you! Has God ever told a man he mustn’t piss?”

François Toumignon had won his bet.

These incredible words, which left all who heard them in a state of. helpless amazement, had hardly died away when Nicolas the beadle was seen approaching with great strides. A sudden hastiness was observed in his footsteps that was quite incompatible with the dignified gait associated with his office, ordinarily accompanied by the discreet but firm tap-tap of his halberd on the flagstones. This reassuring sound gave the faithful a comfortable feeling, that they could say their prayers in peace under the protection of this tower of strength which watched over them, with its fine mustaches and its solid foundations, a pair of calves whose muscular equipment and elegant contours would have been an ornament to the main aisle of a cathedral.

On reaching François Toumignon, he addressed a few sharp words to him, in which there was a suspicion of good-natured chaff despite the fact that an outrage had been committed on the sanctity of the church, the like of which no beadle in Clochemerle had ever known or heard of. It was, in fact, the very enormity of the crime which precluded Nicolas from forming a true estimate of it. The motive which had formerly prompted him to aspire to the honorable position of beadle at Clochemerle was not so much a taste for prestige of the kind associated with a post in the constabulary, as a complete physical suitability, for which he was indebted to the mysterious workings of Nature in his lower limbs. His thighs were of fine proportions and outline, fleshy, hard, and with a faultless outward curve in the upper portion, and thus perfectly adapted for molding in purple breeches which attracted all eyes to this example of anatomical perfection. As for Nicolas’ calves, finer far than those of a Claudius Brodequin, they owed nothing to artifice. All that bulge in his white stockings was due to muscle, and to muscle alone; a splendid pair they were, like heads of oxen beneath the yoke, enabling him at each step forward to make a majestic effort which swelled and shifted their noble substance. From the groin to the tips of his toes, Nicolas could have borne comparison with the Farnese Hercules. These fine physical endowments inclined him far more to displays of his legs than to disciplinary interventions. Thus it was that, taken aback by the novelty of this form of sacrilege, all he could find to say to the culprit was:

“Shut your mouth and clear out at once, François!”

This was indeed the language of restraint, lenient, kindly words to which François Toumignon would assuredly have yielded, had it not been a day which followed a night of carousal during which he had drunk an imprudent quantity of the best Clochemerle wine. There was another circumstance which made the matter still worse, that near the font were standing his witnesses, Torbayon, Laroudelle, Poipanel, and others, watching attentively and silently jeering at him. Nominally partisans of Toumignon, they could not believe that their man, an unkempt untidy fellow, unaccustomed to wearing a collar, unshaven, with crooked tie and rumpled hair, and a wife whose notorious infidelity was a source of amusement in the town, could offer any serious resistance to the massive Nicolas, with all his prestige as a beadle, wearing his crossbelt, his two-cornered hat with plumes, a sword at his side, and carrying his fringed halberd with its studded handle. Toumignon was conscious of this lack of confidence in him, which was giving the beadle the upper hand from the start. This had the effect of steadying him, and he continued stubbornly to grin in the direction of the Curé Ponosse, a silent figure in the pulpit. Nicolas thereupon resumed his efforts, slightly raising his voice:

“Don’t be a fool, François! Get out, clear off, and double-quick, too!”

His tone was threatening, and his words were followed by smiles among the spectators, somewhat half-hearted perhaps, but an indication of a firm intention on their part to side with authority. These smiles only served to increase Toumignon’s exasperation at the consciousness of his own weakness, in face of the immobility and glamour of Nicolas’ bulky form. He replied:

“I’m not going to be turned out by you, with all your fancy dress!”

It may well be supposed that Toumignon thought by these words to disguise his defeat and follow it up promptly by an honorable retreat. With such words as these a proud man may still preserve his self-respect. But at this moment an incident occurred which put the finishing touch to the general consternation. In the midst of the group of pious women and Children of Mary assembled near the harmonium, a salver placed there for the collection suddenly fell with a loud clatter. It spread over the floor a regular hail of two-franc pieces, every one of which had been provided by the Curé Ponosse himself, who made use of this innocent stratagem to incite his flock to greater liberality, for they were far too inclined to resort to copper coin for the purpose of their offerings. At the idea of so many good two-franc pieces becoming lost, stolen, or strayed in every corner of the church, within reach of a lot of wretched vulgar gossips whose avarice far exceeded their piety, those pure and saintly maidens, completely losing their heads, squatted down to search for the coins amid the din and clatter of chairs pushed aside or turned topsy-turvy. All the while they shouted out one to another their estimates of a total haul which was continually increasing. Drowning this tumultuous chorus of silvery voices, another voice, shrill and piercing, was heard to utter this cry, which settled the matter once and for all:

“Get thee behind me, Satan!”

It was the voice of Justine Putet—always to the fore when there was a good fight on hand—who was stepping into the breach which the Curé Ponosse had failed to hold. The latter, as we have seen, was a feeble orator who, on an occasion when he was precluded from preaching an ordinary sermon in which there was no need for inventiveness, hadn’t an idea in his head. Utterly overwhelmed by the scandalous outbreak, he besought Heaven for some kind of inspiration which would enable him to restore peace and order and secure a victory for the cause of right and justice. Alas, at that hour no angel of light was hovering over the region of Clochemerle. The Curé Ponosse was at his wit’s end; he had grown too accustomed to count upon the indulgence of Heaven for the unraveling of human entanglements.

But Justine Putet’s cry had made the beadle’s duty plain. Going up threateningly to Toumignon, he apostrophized him in a vigorous outburst heard all over the church:

“Once again I’m telling you to get out of that door immediately, or I’ll kick your behind for you, François!”

At this point, from confused and beclouded brains, a whirlwind of pent-up passions broke loose, with such violence that each and all forgot themselves, forgot the majesty of that holy place, and cared not how loud they spoke. Words came rushing to the tongue, recklessly and at random, and were hurled from the mouth with diabolical violence, propelled by the awful forces of mental agitation and tumult. The situation should be clearly understood. Stirred by two hostile enthusiasms, religious and Republican, Nicolas and Toumignon were preparing to raise their voices to such an extent that the whole church could follow the details of their quarrel; and these would inevitably be repeated by those there assembled to the whole of Clochemerle. Their vanity was too deeply involved, their principles too much endangered, for either adversary to be able to give way. There would be insults from both men, blows given and received. The same insults, the same blows would be placed at the service of the good cause as of the bad; and indeed neither cause would be distinguishable from the other, so confused would be the conflict, so deplorable the abuse on either side.

Nicolas’ insulting threat is parried by Toumignon, who has taken up a safe position behind a barrier of chairs:

“Come on and do it, then, you good-for-nothing idle dog!”

“I’ll do it before you know where you are, you wretched little pygmy!” Nicolas replies.

Any reference to his unfortunate physique drives Toumignon into a frenzy. He shouts out:

You may be a beadle in full dress and, as such, in a position to disregard insinuations of any kind. But there are nevertheless certain words which constitute an irreparable outrage on your manly self-respect. Nicolas completely loses all self-control.

“Coward yourself, you wretched cuckold!”

At this direct hit Toumignon turns pale, takes two steps forward, and plants himself aggressively under the beadle’s very nose:

“Say that again, you curé’s lap dog!”

“Cuckold, then, for the second time! And let me add, a woman’s good-for-nothing!”

“Some men’s wives couldn’t go wrong if they wanted to, you lousy swine! That yellow hide of hers won’t get your wife many customers. You’ve been hanging round Judith, haven’t you?”

“I’ve been hanging round her? I have? Don’t you dare say such a thing to me!”

“Yes, you swine, you have. But what did she do? She just kicked you out. She sent you away with a flea in your ear, she did, you church dummy!”

It will be seen from the foregoing that no power on earth can now restrain these two men, whose honor, with the subject of their wives dragged into the dispute, has been publicly assailed. It so happens that Mme. Nicolas is seated in the nave. She is a woman of faded appearance, regarded by none other as a rival, but Nicolas’ calves have brought her many secret enemies. Many eyes are turned in her direction. It is true she has a yellow skin! But more than all else the quarrel has brought to mind a picture of Judith Toumignon, in all her splendor, with the rich abundance of her lovely milk-white flesh, her bold sweeping contours, her magnificent projections of poop and prow. A mental image of the lovely Judith invades and fills the holy place and reigns supreme, a frightful incarnation of lewdness, a satanic vision, convulsed and writhing in the shameful pleasures of guilty love. It makes the chorus of pious women shudder in terror and disgust. From this forlorn group there mounts upwards a sound of wailing and lamentation, muffled and long-drawn-out, like that of Holy Week. One woman, shocked and revolted, falls in a swoon on the harmonium, which gives out a sound as of distant thunder as though a herald of the wrath to come. The Curé Ponosse is bathed in perspiration. Disorder and confusion have reached their utmost limit. Shouts and cries, now uttered in fury, are still resounding everywhere, bursting like bombs beneath the low-vaulted roof, whence they rebound and strike the figures of horror-stricken saints.

“Coward!”

“Cuckold!”

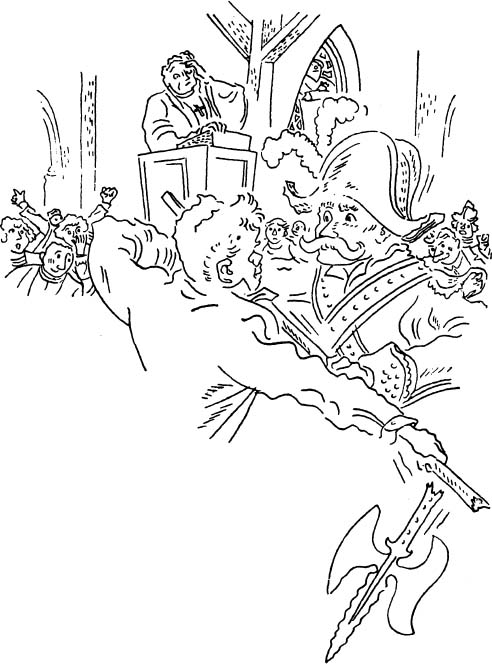

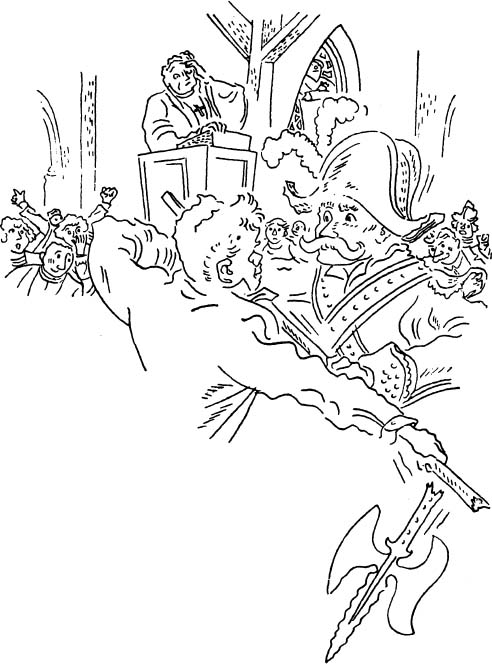

There is now pandemonium, utter and complete, blasphemous, infernal. Which of the two moved first, which struck the first blow, none can tell. But Nicolas has raised his halberd like a bludgeon. He brings it down with full force on Toumignon’s head. The halberd is a weapon intended rather for ornamental purposes than for active use, and the staff has gradually become worm-eaten as the result of prolonged sojourn in a cupboard in the vestry. This staff breaks, and the best portion of it, that which bears the spearhead, rolls on the ground. Toumignon hurls himself upon the shaft, which Nicolas is still holding, seizes it with both hands, and, with this fragment of wood between himself and the beadle, aims a series of treacherous kicks at the base of his stomach. This attack being concentrated upon attributes of his ecclesiastical functions, that is, his thighs and purple breeches, Nicolas thereupon gives a display of crushing and destructive vigor, by which Toumignon is hurled backwards, thereby throwing a whole row of chairs into confusion. Feeling that victory is already within his grasp, the beadle dashes forward. Thereupon a chair, held by the back, is brandished aloft by someone, with the intention of hurling it through the air in a devastating flight which would doubtless be brought to a full stop with shattering force on someone’s head—Nicolas’ for choicer But that flight never takes place. The chair has come into violent contact with the beautiful colored plaster statue of Saint Roch, the patron saint of Clochemerle, the gift of no less a person that Baroness Alphonsine de Courtebiche. Saint Roch receives the blow on his side, he reels, sways a little on the edge of his pedestal, and finally collapses into the font which stands just beneath him, where, alas, he is guillotined on the sharp edge of the stone. His haloed head rolls away to join Nicolas’ halberd on the flagstones, and his nose is broken, which straightway deprives the saint of all appearance of a personage rejoicing in eternal bliss and a protector from plague. The catastrophe is followed by inexpressible confusion.

In their consternation and dismay, a long-drawn-out groan of horror escapes from the group of pious women. Timidly they make the sign of the Cross in face of these first fruits of the Apocalypse which are being unveiled before their eyes at the back of the church. There is now a ceaseless booming roar of sound arising from the abominable sorceries of the Evil One, embodied in the sallow unwholesome figure of Toumignon, known for a drunken dissolute person, who in addition has just revealed himself as a savage iconoclast, a man who would trample on anything, a man ready to defy Heaven and earth. These pious women, gripped by the fear of divine wrath, are awaiting the thunderous sound of an elemental clash of the stars in Heaven. They expect a rain of ashes to fall over Clochemerle, singled out like some new Gomorrah by the powers of vengeance because of the shameless use which Judith Toumignon, the Scarlet Woman, has made of her evil beauty. Moments of unspeakable terror are these. The pious women utter bleating cries of fear, while they press to their insignificant bosoms scapularies shriveled by their sweat. The Children of Mary are transformed into swooning maidens convinced of pursuit by hordes of demons with monstrous attributes, whose obscene and burning tracks they feel upon the trembling flesh of their virgin bodies. An overwhelming sense of the approaching end of all things, mingled with odors of death and of carnal love, sweeps through the church of Clochemerle. It was at this moment that Justine Putet, with undaunted heart and stirred by the hatred of men with which an enforced virginity has filled her, gives indication of her strength. This skinny form, the color of an old quince, has dreadful growths of superfluous hair, and its withered skin falls into creases at points where, in other women, it is a covering for a gentle rich abundance beneath. This scraggy form, this unremitting Fury, is hoisted on to a prie-dieu and from there, with a look of defiance at the incompetent Ponosse, points out to him, in a blaze of warlike passion, the road to martyrdom by intoning an ecstatic miserere of exorcism.

Alas, not a soul will follow her example! The other women, creatures with no backbone, who can only stand and moan, good enough for housework or nursing children but mere ninnies and simpletons for the most part, congenitally disposed to give way on every occasion in accordance with the tradition of woman in subjection—all these women stand gaping open-mouthed. With their hearts melting within them, a sinking in the pits of their stomachs, and their legs giving way beneath them, they wait for the heavens to rain fire or the angels of extermination to come rushing upon them like squads of rural constables.

In the meantime, the fight has begun again at the back of the church with renewed intensity. No one knows whether the beadle is now attempting to avenge Saint Roch, martyred in effigy, or the insults to Mme. Nicolas and the Curé Ponosse. Probably no distinction is made between either duty in the unsubtle beadle’s mind, for his head is better adapted for wearing ceremonial plumes than for carrying ideas. However that may be, Nicolas charges down like a bull in blind rage upon Toumignon, who is crouching back against a pillar with a face that shows a crafty expression and a greenish pallor, like that of a hunted criminal waiting for an opportunity to plunge his knife. Nicolas’ broad hairy hands swoop down on the little man and clasp him with the strength of a gorilla. But in Toumignon’s puny frame there is stored up a reserve of power, born of rage and fury, that is quite beyond the ordinary. He has an ingenuity for causing pain; which enormously increases the effectiveness of the weapons he uses, his nails, his teeth, his elbows, and his knees. Giving up all hope of being able to tackle a massive frame encased in gilt ornaments and buttons, Toumignon makes a treacherous and violent attack with his feet, aimed at the most vulnerable portions of Nicolas’ anatomy. Then, taking advantage of a momentary lack of concentration on his adversary’s part, with a violent tug he loosens the lobe of his left ear. Blood makes its appearance. The bystanders think that the time has come to intervene.

“Oh, but you don’t want to fight!” So say these good hypocrites, rejoicing at the bottom of their hearts over this incident, which will make a priceless subject for discussion during the long winter evenings.

They throw their arms tightly around the combatants’ shoulders, trying to reconcile them. But, in so doing, they themselves become involved with the distorted limbs of two men mad with rage and fury. Several of these half-hearted peacemakers, their balance upset by shoves and pushes which spin them around like tops, are sent flying and collapse onto piles of chairs which are dispersed in all directions with a resounding clatter. On this confused heap, studded with a few treacherous nails and numerous projecting wooden pegs, Jules Laroudelle impales himself with a cry of pain, while Benoît Ploquin tears his Sunday trousers with a despairing “Good God!”

So violent is the uproar at this moment that it has just aroused the sexton Coiffenave from the semisomnolent state into which his deafness habitually plunges him. This individual spends his time in a small dark side chapel where, thanks to his dull colorless skin, he stays unnoticed, while with secret enjoyment, he occupies himself in spying on people in the church. With his hearing miraculously restored by a confused uproar, excessively unusual in a building normally devoted to prayer and silence, he cannot believe his ears. He has long ceased to call upon them for the empty purpose of enabling him to participate in the vain unrest and fruitless tumult of his fellow men. See him, then, stealing to the edge of the main aisle, where he throws a glance of amazement at this gathering of the faithful, all of whom have turned their backs to the altar and are now facing the door. Towards them he now makes his way, jogging along in a pair of floppy loosely fitting slippers. He emerges in the thick of the fray, and at a moment so ill chosen that Nicolas’ big hobnailed boot crushes several of his toes. The sharp pain of this gives the sexton a sense of unaccustomed pressing danger, constituting a grave threat to the interests of religion, a source from which he derives certain small remunerations. In this lonely man’s mind there is one thought which stands out above all others—his bell, which is his pride and also his friend, the only friend whose voice he can clearly hear. Without a moment’s further thought he springs to the big rope and hangs upon it with a fierce energy which gives the old monastery bell, the “blackbirds’ bell,” such momentum that he is dragged aloft to truly impressive heights. To see him thus, swinging to and fro and rushing skywards, creates an illusion of some heavenly being, spending his leisure in playing a practical joke, holding suspended in mid-air, at the end of an india-rubber band, a grinning goblin chiefly noteworthy for the large patch on the seat of his ample breeches. Coiffenave launches a formidable tocsin which makes the beams of the belfry creak and groan.

At Clochemerle the tocsin had not been heard since 1914. It is not hard to realize the effect of these alarming sounds on the morning of the annual fête, a morning of such lovely sunshine that all windows are wide open. Within a few seconds every living being throughout the town who is not at Mass is to be found in the main street. The most determined tipplers leave their glasses half empty. Even Tafardel tears himself away from his papers, looks around hurriedly for his panama, and goes down the hill from the town hall with all the speed he can muster, wiping his spectacles and saying over and over again: rerum cognoscere causas. For in the course of his reading he has picked up a selection of Latin maxims which he has copied into a notebook; and this assures him of superiority over the vulgar products of elementary schools.

Within a few moments a large crowd has collected in front of the church. Their eyes arc met by our two combatants, Nicolas and François Toumignon, bursting through the door, desperately locked together in a pugilist’s embrace, dragging the whole bunch of peacemakers at their heels, both of them panting, bleeding, and in an altogether lamentable condition. At last they are separated, still exchanging gross and violent insults, issuing fresh challenges, and swearing to meet again shortly and show each other no mercy. In the meantime each is congratulating himself on having given the other a damned good hiding.

The next to appear are the pious women. They are a picture of pathos, with downcast eyes, uttering no word, and rendered precious as sacred vessels with the scandalous secrets of which they have now become the repositories. Soon they will be seen mixing with the various groups, where they will sow the fruitful seed of gossip, swelling these prodigious happenings to legendary proportions and paving the way for endless discord and irrefutable slander. These forlorn women now have an exceptional opportunity for appearing important. It will make up to them for the insults which men have heaped upon them. By means of this exceptional opportunity, through Toumignon, they can hurl Judith from the pedestal she has too long occupied, that woman whose triumphs of concupiscence have brought upon them a long-drawn-out and wicked martyrdom. This opportunity these pious women will never allow to escape them, not even at the cost of a civil war. And civil war will be its outcome. These charitably minded ladies, whose spotless persons form a rampart for the protection of virtue against which no man of Clochemerle has ever dreamed of launching an attack, will assuredly have done nothing to allay its outbreak. But at this stage, with different versions still prevailing, they avoid all definite statement and are content to do no more than prophesy that the insult to Saint Roch will result in a second outbreak of plague at Clochemerle—or at the very least phylloxera, the scourge of vineyards.

Like a captain leaving his ship in distress, with his biretta tilted back and his bands in disorder, the last to come out is the Curé Ponosse, with Justine Putet at his elbow, holding in her arms the mutilated head of Saint Roch. She looks for all the world like those dauntless women who in days gone by used to go to the Place de Grève to gather up their lovers’ severed heads. Over this saintly relic, swollen by the water of the font like the corpse of a drowned man, she has just sworn an oath of vengeance. In a state of sublime exaltation. like some new Jeanne Hachette, and fully prepared for the noble task of a Charlotte Corday, for the first time in her life the old maid feels coursing through her lean flanks, which have never known a caress, intense spasmodic thrills which she has never felt before. Close alongside the Curé Ponosse, she struggles to put some determination into him, and to bring him around to a policy of violence which shall link up with the traditions of the great epochs of the Church’s history, the epochs of conquest.

But the Curé Ponosse is endowed with the obstinacy of feeble natures, capable of great efforts to prevent any disturbance of a peaceful existence. Justine Putet finds herself confronted by a listless unresponsive apathy, in face of which all her hopes are dissolved into thin air. As he walks along he listens to her with an air of concentration which appears like acquiescence. By taking advantage of a momentary silence on her part, he remarks:

“My dear lady, God will be grateful to you for your courageous conduct. But we must leave it to Him to settle difficulties which are beyond the scope of our poor human intelligence.”

This the old maid, whose fighting spirit demands active measures, regards as merely ludicrous. She is about to protest. But the Curé Ponosse adds:

“I can decide nothing until I have seen the Baroness, who is president of our congregations and benefactress of our beautiful parish of Clochemerle.”

No words could have been better chosen for stirring up bitterness and venom in Justine Putet’s heart. She feels that her path will always be blocked by that arrogant Courtebiche woman, who in her youth has followed the primrose path and is now posing as a model of virtue in order to secure an esteem which depravity of morals can no longer afford her! Here is an opportunity to score off this Baroness with her lurid past. Justine Putet has certain knowledge which is doubtless not available to the curé. The feelings of the Baroness need no longer be considered. Justine Putet decides to make a complete revelation.

They arrive at the presbytery, where the old maid wishes to gain entrance. But the Curé Ponosse waves her aside.

“Monsieur le Curé,” she insists, “I should like to speak to you confidentially.”

“Let us leave it for the moment.”

“And supposing I asked you to take my confession?”

“My dear lady, this is not the time for it. And besides, I received your confession two days ago. If the sacraments are to retain their proper solemnity, we must not be continually having recourse to them for comparatively trivial reasons.”

Once again Justine Putet has failed. With a frightful grimace she drinks the hemlock. Then a grating sound is heard, half chuckle, half sneer:

“It’s a pity I’m not one of those lewd creatures with dirty stories to tell you! They are so much more interesting to listen to!”

“Let us beware of judging others,” the Curé Ponosse replies, in a smooth dispassionate tone of voice. “The seats at God’s right hand are few in number, and they are reserved for those who have shown charity towards their neighbor. I give you temporary absolution. Go in peace, dear lady.”

And the Curé of Clochemerle closes the door in her face.