Chapter 6: The modern OED

So that was it, the world now had a complete dictionary of English based on historical records including etymologies, orthographies and quotations. But, once again, was it complete? A-Ant was printed in 1884, forty-six years before the first edition was published. Had any more words in that range been added to the language during those forty-six years? Of course they had (aeroplane and appendicitis are just two important examples), and yet more words would have been discovered by the readers. Assembling this Dictionary is like hill climbing, as you rise to a peak another one rises behind it, and that next peak had already been growing. It consisted of a pile of slips which, for whatever reason had missed the first edition, plus all of the new words that had emerged during the many years spent assembling it. Craigie, Onions and the team returned to their lexicographical labours producing the first supplement to the Dictionary in 1933, and in that same year the Dictionary itself was reprinted as twelve volumes plus an important title change: this was the first version to be officially named The Oxford English Dictionary.

Was this change of name justified? Of course it was. Despite all of the ups and downs of Murray’s early years and through a growing awareness that the project swallowed up money with no foreseeable return, the Oxford University Press continued to support this ‘greatest enterprise of its kind in history’. And there was a return, not financial perhaps and undoubtedly not measurable: kudos. There is little doubt that the reputation of the Press and the University has been enhanced enormously by its investment in the OED and that Oxford has established itself as the undisputed guardian of the English language, a language which during the 20th century became the most important world tongue.

The supplement extended the Dictionary by 867 pages (an increase of roughly five percent) containing many new words plus new senses and amplifications of existing ones. It was given free to those who had splashed out fifty-five pounds on the 1928 version: some compensation for the fact that the 1933 printing, with the supplement included, could be purchased for a mere twenty-one pounds!

What next? Well, not a lot, at least not for a while. The remaining slips were stored away or given to other projects, the Dictionary team was disbanded, and the reading programme shut down. And that should have been the end of the line. But of course there was a rebirth. In 1957 work started on a further supplement under the editorship of Robert Burchfield, a New Zealander and then a member of St Peter’s College, Oxford. Burchfield had been recommended by an old warrior of the OED, Charles Onions who himself worked on the new supplement until the mid-sixties. Burchfield reinstated the reading programme, pulled the old slips from the thirties out of store and set up shop in accommodation near to the OUP building in Walton Crescent. His supplement was issued in four volumes between 1972 and 1986. It incorporated much of the 1933 supplement and many new words, some defined by their inventors (e.g. hobbit by one J R R Tolkien). The four volumes defined over 50,000 words including many new scientific and technical words.

And as the OED modernised so too did its means of production, the second supplement was printed by lithography rather than letterpress. The technology of microfiche and microtext had also come into its own so, in the year before the appearance of the second supplement, the entire first edition of the OED had been reduced to two volumes sold together with an essential magnifying glass. Though Burchfield expanded the Dictionary through the introduction of his supplement, he also gained a reputation as a word dropper. He excised a significant number of words inherited from the first supplement, many of which had only a single recorded usage. Some argued that this was against the OED spirit.

Of course, Burchfield, as Murray before him, relied heavily on the volunteer readers and one of these stands head and shoulders above the others. Her name was Marghanita Laski, a graduate of Somerville College, Oxford, a journalist, novelist, panellist on the BBC’s ‘Any Questions’ and known 'for her beauty, her forceful personality, and her obsession with religious and secular beliefs'. She contributed a whopping 250,000 quotations to the Dictionary.

The first edition still existed in its 1933 form and the second supplement (which incorporated the first, mostly) had a separate existence. This was not good. If you could not find a word in the first you had to consult the second. Clearly the two needed to be integrated and yet more new words added – and the technology was now available to do this electronically. IBM donated both the computer and the staff to take on this massive task: an army of 120 keyboard operators typed the entire sixty million words of the combined Dictionary into an IBM 4351 mainframe computer where clever software merged the two parts. This second edition was completed under the editorship of John Simpson and Edmund Weiner and added approximately 5,000 new words to the Dictionary.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Computerising the Dictionary in the late 1980s cost $13.5 million spent over a period of five years

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

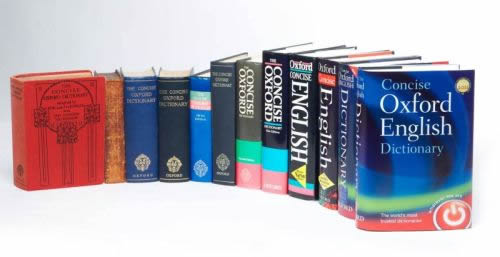

Digitising the OED was an immense technical and lexicographic task which was completed in 1989 with the issue of edition two as a twenty volume set containing over half a million words and nearly two and half million quotations. The page count had now risen to nearly 22,000. The price for this edition in 2015 was £750. And of course the big dictionary has spawned many smaller variants: Little, Pocket, Concise, Shorter, Compact and so on. Then there are the specialised dictionaries: for schools, for advance learners and more. So many streams of income yet still no profit?

Some of the dictionaries spawned by the OED

So, what next for the OED? A truly digital version of course: the CD version of the second edition was made available in 1992. Then, in 1993 and 1997, three volumes of additions were printed and added to the CD version. Following that came the obvious next step, in the year 2000 the updated version of the Dictionary was made available online together with search tools which were superior to those available with the CD versions.

This second version of the Dictionary was good, but by no means perfect. The first had been absorbed into it virtually unchanged except for the correction of obvious errors. Naturally the quality and coverage of some definitions it listed had declined with the passage of time: some of them were more than a century old. So, what’s happening to the OED nowadays and into the future?

In 1993 John Simpson became the editor of an entirely updated edition of the Dictionary. The third edition is probably the last because there are no plans to print it – it will grow as the language grows in a way that a print edition can never do. Solely online at present this version entails a complete and rolling revision of the previous editions now incorporated into it, plus the addition of new words, definitions and source quotations as they arrive from the lexicographic team and its modern-day volunteers. It is almost a living thing, growing with the language. It has a team of 120 scholars, research assistants, systems engineers, and project managers in Oxford and New York, backed by 200 or so consultants and readers generating some 17,000 quotations per month. First made available online in the year 2000 alongside the digitised second edition, it has rapidly diverged from its predecessor as three monthly updates have been released. In the relaunch of 2010 many improvements were made including full integration of the historical thesaurus and online access to a version of the second edition was dropped.

Over one third of the previous edition had been revised and updated by 2015 and even when this mammoth task is completed the work will go on as new words are added and alternative examples of the use of old words are discovered. A personal subscription to the service, accessed via the Web of course, costs about £250 per year. New words added in June of 2015 totalled just over three hundred and included: e-cigarette, vaping and retweet. Even ‘unfriend’ is listed. What a ghastly modern word! Not really, the OED includes a quoted use of it dating back to 1659! And so the language rolls on. Is it good? It just is.

Dictionary growth through the ages