One morning in April, in the year when the old history of the Kurelu came to an end, a man named Weaklekek started down the mountain from the hill village of Lokoparek. He did not go by the straight path, which descends through a tangle of pandanus and bamboo onto the open hillsides, but instead went west, through the forest beneath the cliff. The cliff was a sheer face of yellow limestone black-smeared with green algae, and the tree line of its crest wavered in mist. With the sun rising behind it, the mist appeared illumined from within.

One morning in April, in the year when the old history of the Kurelu came to an end, a man named Weaklekek started down the mountain from the hill village of Lokoparek. He did not go by the straight path, which descends through a tangle of pandanus and bamboo onto the open hillsides, but instead went west, through the forest beneath the cliff. The cliff was a sheer face of yellow limestone black-smeared with green algae, and the tree line of its crest wavered in mist. With the sun rising behind it, the mist appeared illumined from within.

The rains of April had been heavy, and the path was a glutinous mire pocked by the hooves of pigs; he walked it swiftly, his bare feet feeling cleverly for the root or rock that would give them purchase, and at the stream he ran across the log. The path climbed steeply to a grove of tropical chestnuts, tall, with small leaves of green-bronze, and there he paused a moment to peer out through the forest shades. Though he could not see it, the sun had mounted from behind the cliff. Below, the valley floor and its far wall steamed in an early light, but the forest would stay dank and somber until the cloud above his head had burned away.

Weaklekek moved on to a point where the wood ended in a clearing between great boulders; the wood edge leapt with plants of light and shade, the most striking of which was a great rhododendron, its white blossoms broader than his hand. In the shadows and clefts of the boulders, wood ferns in wild variety uncurled from among the liverworts and lichens, the mosses and silver fungi. The ferns were the triumphant plant of the high forest, with species numbering in the hundreds, but Weaklekek was oblivious of the ferns, of all the details of his world which could not immediately be put to use. The ferns, like the mist hung on the cliffs, the squall of parrots echoing on the walls, the sun, the distant river, were part of him as he was part of them: they were inside him, behind the shadows of his brown eyes, and not before him. He would see a certain fern when he needed it for dressing pig, and another from which pith was taken to roll thread, but the rest withdrew into the landscape.

The experience of his eye was not his own. It was thousands of years old, immutable, passed along as certainly and inevitably as his dark skin, the cast of his quick face. These characters were more variable than experience, for experience was static in the valley; it was older than time itself, for time was a thing of but two generations, dated by moons and ending with the day in which he found himself. Before the father of Weaklekek’s father was the ancestor of the people: his name was Nopu, and he came from the high mountains with a wife and a great bundle of living things. Nopu’s children were the founders of the clans, with names like Haiman, Alua, Kosi, Wilil, and they had opened the life bundle against Nopu’s will, releasing the mosquitoes and the snakes upon all the people, the akuni, who came after.

Nopu was the common ancestor, but perhaps he was also that first Papuan who, one hour in the long infinity of days, from the forest of the mountain passes, saw the green valley of the Baliem River far below him in the sunny haze. How many years, or centuries of years, this man had wandered out of Africa and Asia may never be known, for he traveled lightly, and he left no trail.

Before the coming of Nopu, in the millenniums of silence, the greatest of the valley’s creatures was a bird, the cassowary. Birds of paradise, red, emerald, golden, and night-blue, fluttered, huffed, and screeched among the fern and orchid gardens of the higher limbs. Hawks and swiftlets coursed the torpid airs, and the common sandpiper of Africa and Eurasia flew south like a messenger from another earth to teeter on the margins of its streams. In stands of great evergreen araucaria, in oak-chestnut forest and river jungle, a primitive fauna of small marsupials, with a few bats and rodents, prospered in habitats long since pre-empted, elsewhere on the earth, by the cats and weasels, dogs, bears, hoofed animals, and apes: the marsupials, stranded on these mountain outposts of the Australian continental shelf by the wax and wane of ice-age seas, became carnivores and insectivores and, in the wallabies and kangaroos, strange herbivores of the high grasslands.

Then that first man—perhaps Nopu, perhaps another—reached the coast, and eventually the inner mountains; he occupied the valley, with his women and children, his bow, bamboo knife, and stone adze. Like the mountain wallaby, the cuscus, and the phalanger, he had cut himself off from a world which rolled on without him. The food in the valley forests was plentiful, and he had brought with him—or there came soon after—the sweet potato, dog, and pig. The jungle and mountain, the wall of clouds, the centuries, secured him from the navigators and explorers who touched the coasts and went away again; he remained in his stone culture. In the last corners of the valley, he remains there still, under the mountain wall. His name is not Nopu, for he is the son of Nopu’s son, but he is the same man.

So now he paused to take in his surroundings, standing gracefully, his weight balanced on his right leg and upright spear. His right hand, holding the spear, was at the level of his chin, and the spear itself, sixteen feet long, rose to a point which drew taut, as he stood there, the stillness of the forest. The spear was carved from the red wood of the yoli myrtle, and a pale yoli, its smooth bark scaling like reptilian skin, stood like the leg of a great dinosaur behind him.

Weaklekek was darker than most Dani, a dark brown which looked black, and the blackness of his naked body was set off by the white symmetries of his snail-shell bib. He looked taller than his five feet and a half, lean and cat-muscled, with narrow shoulders and flat narrow hips. At rest on the long spear, he gave an impression of indolent grace, a grace by no means gentle but rather a kind of coiling which permitted him to move quickly from a still position.

He stood there watching, watching. The landscape as it was, had always been, his eye shut out. The stir of change, the detail out of place, was what he hunted: a distant movement, a stray smoke, a silence where a honey eater sang, a whoop of warning. Across the valley other men stood watching at this moment, under the long spear, for today there would be war.

From where he stood, still as a snake, the southern territories of Kurelu’s Land spread before him. The narrow gully of the upper Aike dropped away on his left hand, the hill brush of its edges giving way as the land leveled to a riverain forest ruled by casuarina. Before him rose the smoke of morning fires, though the villages themselves—Abukumo, Homaklep, and Wuperainma—were not visible. On his right hand the cliff curved outward from the valley rim; it declined rapidly to a rocky hill, and finally a steep grassy slope, which plummeted for several hundred feet into a stand of giant araucarias at its foot. The three villages lay in a kind of pocket in the mountain flank, between the steep hill and the Aike River.

The araucarias were straight and tall, well over one hundred feet, with tiers of branches curving upward, and needles clustered in great balls, like ornaments. The araucaria was an ancient tree, disappearing from the valley, from the world; each needle of this tree grew very old, refracting the sparkle of the dew for forty years and more.

Directly below Wuperainma a small wood surrounded lowland brooks. The far part of the wood could be seen from where he stood, and beyond it a fringe of long-grass savanna, scattered with bushes, sloped to the bottom lands and drainage ditches of the sweet-potato fields. The bed of purple, veined by silver water, spread unbroken for a mile, ending at a far line of trees. Beyond the trees a marshy swale marked the frontier; it continued into no man’s land, surrounding a low rocky rise, the Waraba, and the near face of a pyramidal hill, the Siobara. The Siobara stood in Wittaia territory, and Wittaia fields and villages lay to both sides of it. Behind the Siobara a hairy spine of casuarina marked the course of the Baliem along the valley floor, and beyond the river a subsidiary valley mounted steeply to the cloud forest beneath the western walls.

The trail wound down the slopes toward Wuperainma, passing alternately through low woodland and open brush; the bare feet of many years had beaten away the grass and the thin topsoil, laying bare the chalky white of a fine quartzitic sand. When dry, this sand was as soft as powder, but in the rain it glazed to a smooth hardness. The white sand erupted in great spots across the valley, and from where Weaklekek walked three patches of it could be seen, like snowfields, at the base of the Siobara and on the farther hills to the southwest.

The limestone soil supported many plants in various stages of new flowering. Flowering and fading occurred in the same plant at once, the blossoms and burning leaves, for there was no autumn in the valley. The leaves died one by one and were replaced, so that the foliage of each plant was brilliant red and green against the hillside. The equatorial monsoons which brought a rainy season to the coasts had small effect here in the highlands; from moon to moon, the rainfall varied little. Winter, summer, autumn, spring were involuted, turning in upon themselves, a slow circling of time.

Weaklekek moved swiftly down the mountain. At a certain point he paused and called out toward the cliff—We-AK-le-kek! And when the voice returned to him, AK-le-kek,-le-kek, he grinned uneasily, for this was the voice of his own spirit. On the lower slopes the pigeon, yoroick, called its own name dolefully, and from far below, where the sun was shining, the bird was answered by the high voice of a boy.

At dawn that morning the enemy began chanting, and the chant, hoo, hoo, hoo, ua, ua, rolled across the fields toward the mountains. The fields were tattered still with mist, and a cloud hung on the valley floor, submerging the line of trees at the frontier. A man ran past the wood of araucaria, called Homuak after the spring which, rising silently from among the bony roots, flows out and dies in the savanna; Homuak lies at the foot of the steep hill near Wuperainma. He cried out urgently, his voice a solitary echo of the wail from behind the mist. The call was taken up on the far side of the hill and trailed off northward to the villages of Kurelu.

At dawn that morning the enemy began chanting, and the chant, hoo, hoo, hoo, ua, ua, rolled across the fields toward the mountains. The fields were tattered still with mist, and a cloud hung on the valley floor, submerging the line of trees at the frontier. A man ran past the wood of araucaria, called Homuak after the spring which, rising silently from among the bony roots, flows out and dies in the savanna; Homuak lies at the foot of the steep hill near Wuperainma. He cried out urgently, his voice a solitary echo of the wail from behind the mist. The call was taken up on the far side of the hill and trailed off northward to the villages of Kurelu.

The wood of Homuak was strangely empty. The black robin chat and a yellow whistler sang in the evergreens, in the rich voice of new nesting, and the night’s rain fell in soft drops from the needles. High behind the still village of Wuperainma the sun rolled up onto the rim, and the mists creeping on the fields slowly dispersed. Still the Wittaia chanted, and the answer grew in all the villages.

A puna lizard, two feet long, with dinosaur spines and heavy head, crept out along a branch of araucaria, seeking the sun; its long whip tail, trailing behind, slid silently on the rough bark.

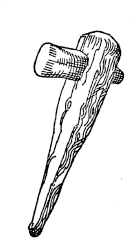

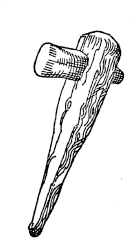

Small bands of warriors were moving out toward the frontier. The men carried their spears and bows and arrows, and the boys ran behind them. A figure climbed slowly to the top of a kaio, one of the many lookout towers visible from the wood; the kaio is built of tall young saplings bound into a column by liana thongs, and rises to a stick platform some twenty-five feet above the ground. The kaios, erected in defense against raids upon the gardens, march across the distances like black lonely trees. At the base of each kaio is a thatched shelter, and here the warriors assembled, leaning their spears against the roof.

Beyond the kaios and gardens lies a thin woodland, then a swale of cane and sedge, and at the far edge of the swale a solitary conifer. The tree marks the edge of the Tokolik, a grassy fairway nearly two miles long, paralleling the frontier. The Tokolik is the high ground of the swamp of no man’s land; on its far side a brushy bog occurs, scattered with dark tannin pools and reeds and sphagnum. The bog extends to the base of a low ridge, the Waraba, and beyond the ridge is the sudden pyramid, the Siobara, like a great fore bulwark of the enemy. In the middle of the Tokolik, just southward of the tree, lies a shallow grassy pool. Small streams have been diked to form the several pools on the frontier; black ducks with striped cinnamon heads frequent the pools, and the people know that the clamor of their flight might betray a raiding party of the enemy.

From the foothills at the south end of the fairway the smoke of a Wittaia fire curled, to lose itself at last against the roll of cloud which cut the valley floor from the dark rim. Near the fire Wittaia warriors were ranked, their spear tips clean as lances on the sky. A larger group, convening on the Tokolik itself, raised a new howling, broken by rhythmic barks. Before the sun had warmed the air, three hundred or more Wittaia had appeared.

At the north end of the Tokolik there is an open meadow. Here the main body of the Kurelu were gathering. Over one hundred had now appeared, and at a signal a group of these ran down the field to the reedy pool. On the far bank a party of Wittaia danced and called. The enemies shouted insults at each other and brandished spears, but no arrows flew, and shortly both sides retired to their rear positions. Because the war was to be fought on their common frontier, the majority of the Kurelu were Kosi-Alua and Wilihiman-Walalua—the southern Kurelu. The northern warriors were not obliged to fight, but the best men of even the most distant villages would appear.

The sun had climbed over the valley, and its light flashed on breastplates of white shells, on white headdresses, on ivory boars’ tusks inserted through nostrils, on wands of white egret feathers twirled like batons. The alarums and excursions fluttered and died while warriors came in across the fields. The shouted war was increasing in ferocity, and several men from each side would dance out and feign attacks, whirling and prancing to display their splendor. They were jeered and admired by both sides and were not shot at, for display and panoply were part of war, which was less war than ceremonial sport, a wild, fierce festival. Territorial conquest was unknown to the akuni; there was land enough for all, and at the end of the day the warriors would go home across the fields to supper. Should rain come to chill them, spoil their feathers, both sides would retire. A day of war was dangerous and splendid, regardless of its outcome; it was a war of individuals and gallantry, quite innocent of tactics and cold slaughter. A single death on either side would mean victory or defeat And yet that death—or two or three—was the end purpose of the war, and the Kurelu, in April, were enraged. Two moons before, three wives of the Haiman kain Maitmo, with another woman and a man, had gone off to a pig feast held by clansmen in a nearby tribe; on their way they had been killed by the Wittaia, and though the Kurelu had come off best in the wars since, the score was not yet evened.

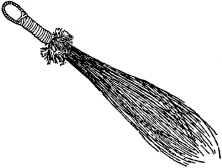

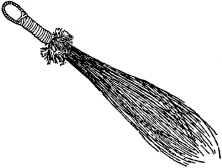

Toward midmorning a flurry of arrows was exchanged, and the armies, each three or four hundred strong, withdrew once more. But soon a great shout rose up out of the distance, and the Kurelu answered it exultantly, hoo-ah-h, hoo-ah-h, hua, hua, hua, like a pack cry of wild dogs. From the base of the tree the advance parties ran to the hillock at the edge of the reed pool, mustered so close that the spears clashed. More companies came swiftly from the rear positions, bare feet drumming on the grass. Here and there flashed egret wands, or a ceremonial whisk; the whisk was made of the great airy feathers of the cassowary bound tight by yellow fiber of an orchid. The wands and whisks were waved in the left hand, while the spears were borne at shoulder level in the right. Four men had black plumes of the saber-tailed bird-of-paradise curling two feet or more above their heads; at the bases of these plumes shone feathers of parrots and other brilliant birds, carmine and emerald and yellow-gold, fixed to a high crown of fur and fiber.

All wore headdresses of war. There were thin white fiber bands, and broad pandanus bands with the brown, gray, or yellow fur of cuscus, opossum, and tree kangaroo. There were crowns of flowers and crowns of feathers, hawk, egret, parrot, parakeet, and lory. Feather bands were stuck upon the forehead, black and shiny with smoke and grease, and matched pairs of large black or white feathers shot straight forward above the ears. Most common of all was a white solitary plume, bound to the forehead by its quill.

On the black breasts lay bibs made up of the white faces of minute snail shells: the largest bibs contained hundreds of snails. Most of these were fastened to the throat by a collar of white cowrie shells, and some of the men wore, in addition, a section of the huge baler shell, called mikak; this spoon-shaped piece, eight inches long or more, was worn with its white concave surface upward, just beneath the chin. Over the centuries, the shells had come up from the coast on the obscure mountain trade routes; they were the prevailing currency of the valley, and a single mikak would purchase a large pig.

Few of the men were entirely without decoration. Even the youngest warriors, the long-legged elege of fourteen to eighteen, wore strings of snails, or a lone feather in the dense wool of their hair. But here and there were naked men—naked, that is, but for the basic dress of every day, worn by all warriors in addition to the shells and fur and feathers: the tight armlets of the pith of bracken fern, braided beautifully upon the wrist or just above the elbow; black fiber strings, one or more, worn at the throat; and the horim, an elongated gourd worn by all but the smallest boys upon the penis. The horim is tied in an erect position by a fine thread of twig fiber secured around the chest; a second thread is looped through a small hole in the horim and down around the scrotum. The horim is often long enough to extend past its owner’s nipples, and is sometimes curled smartly at the tip; many are decorated with a dangling hank of fur.

The advance warriors swept forward past the pool, reflections writhing on the windless water. The clamor increased as the Wittaia came on to meet them, led by a figure whose paradise plumes swayed violently above a head from which white feathers sprayed; he wore a boar’s tusk through his nostrils, hanging down like a white mustache. Both mikak and shell bib gleamed upon his breast, and staring white circles were painted around his eyes.

Two armies of four to five hundred each were now opposed, most of the advance warriors armed with bows, a few with spears. They crouched and feinted, and the first arrows sailed high and lazily against the sky, increasing in speed as they whistled down and spiked the earth. Shrieks burst from the Wittaia, and a wounded Kurelu was carried back, an arrow through his thigh; he stared fearfully, both hands clenched upon a sapling, as two older men worked at the arrow and cut it out. Soon a second man returned, astride the shoulders of a comrade, for this is the way those wounded badly are taken from the field. The battle waned, renewed, and waned again; the fighting was desultory. The day was hot and humid, and as war demands a great amount of heroic leaping and running the warriors very much dislike the heat. But soon the Wittaia began a chanting, heightened by shrill special wails used little by the Kurelu—

dtchyuh, dtchyuh, dtchyuh—woo-ap, woo-ap

woo-r-d-a, woo-r-d-a—

and the Kurelu ran down the Tokolik to battle, in a flying avalanche of feet, spears balanced at the right shoulder, tips angled down. Fighting broke out in the swampy brush toward the Waraba, and, as the line swayed back and forth, the bush fighters remained where they were, crouched down in ambush. A Wittaia low behind a bush, thinking himself unseen, leapt high with a screech as a long spear arched through the bush and caromed off him; he darted away, too shaken to retrieve it, for it had nearly run him through.

Now a shout of derision burst from the Kurelu. On the crest of the Waraba, two hundred yards away, above the battle ground, thirty-odd warriors stood in silhouette. These were men of the Huwikiak clans, from a country two hours distant, on the far side of the Baliem. The territory of the Wittaia borders on the river, and the Huwikiak are Wittaia allies. These men had walked far for the fighting. They streamed down the bank into the swamp to join the battle.

In the early afternoon there came a prolonged lull. The number of warriors was still increasing on both sides, and massed legions were spaced back along the Tokolik for nearly a mile in both directions. Rainstorms, like dirty smoke, filled the high mountain passes, but the clouds hung back along the walls. At the edge of the field a young warrior sighed in agony as an arrow with a long, toothed tip was worked from his forearm with a bamboo sliver.

A wind sprang forward from the east, and the sky darkened. As if caught by the suspense before a rain, the warriors by the pool grew tense, and a Wittaia whoop, breaking the silence, was hurled back on waves of sound. A harrier hawk with a black head, coursing the battleground, flared off and away.

The men assembled in their war parties, and the rear groups closed behind them. A warrior passing the wounded boy seized the bloody arrow as it was twisted free and ran with it toward the front: ordinarily the arrow is kept by the wounded man, and the old man who had removed it shook his head, as if shocked by this breach of custom, moving off toward the rear. The boy, deserted, stood up shakily, staring at the blood running away between his fingers. At the same time, he was proud, and the pride showed.

A man without valor is kepu—a worthless man, a man-who-has-not-killed. The kepu men go to the war field with the rest, but they remain well to the rear. Some howl insults and brandish weapons from afar, but most are quiet and in-obtrusive, content to lend the deadwood of their weapons to the ranks. The kepu men are never jeered or driven into battle—no one must fight who does not choose to—but their position in the tribe may be determined by their comportment on the field. Unless they have strong friends or family, any wives or pigs they may obtain will be taken from them by other men, in the confidence that they will not resist; few kepu men have more than a single wife, and many of them have none.

A kain with long hair in twisted cordy strings stalked forward, followed by another whose shoulders were daubed with yellow clay. U-mue came, in his huge mikak and tall paradise headdress, black grease gleaming in the hollows of his collarbones: the miraculous pig grease, blackened by the ash of grasses, is applied by all warriors whenever it is available, for it is sanctified by ceremony and contributes to morale and health as well as good appearance. It is worn by most men in their hair and on their foreheads, and sometimes in a broad bold band across the cheekbones and the nose, but U-mue smears it all over his head and shoulders, producing a black demonic sheen. He moved separately from the rest, for he claims to be a solitary fighter, with a taste for the treacherous warfare of the underbrush. In truth, he is rarely seen in action, and his claim to five kills is treated with more courtesy than respect. Among the warriors the numbers of kills are well established and are an important measure of degree of kainship.

Despite his claims, U-mue is not thought of as a war kain: he is the village kain of Wuperainma and the political kain of the clan Wilil in the southern Kurelu. The positions of war, village, and political kain are quite separate, though all may be combined in the same man: Wereklowe, the village kain of Abulopak, is also political and war kain of the clan Alua, and one of the most powerful men in all the tribe. Above the kains of all the clans is the great kain Kurelu, and below them are the lesser and younger men with varying degrees of kainship, based on property as well as valor, family as well as worth. U-mue, with four wives and eleven pigs, is a rich man, and his wealth, in company with his ambition and a rare gift for intrigue, has brought him power.

The fighting was closer and more vicious than that of the early skirmishes. More than a hundred men were actually in combat, as opposed to the twenty or thirty who had previously run out in the brief forays: the cries resounded to a strange, monotonous rhythm of twanged rattan bowstrings. The lines remained some fifty feet apart, but a few warriors moved out on the middle ground, crouched low, or down into the brushy swamp, stalking with spears. This is the dangerous fighting, for few men are killed by the thin bamboo arrows. Some may die afterward, but it is the spear which usually accounts for the rare kills made on the battlefield itself. The spear fighters in the brush beneath the Waraba kept low, for an arrow sailed at every upraised head. On the Tokolik, the battle line wavered back and forth, and at one point the Kurelu were swept back to the pool. Kurelu himself came forward then, and his men rallied. When the former line had been restored, the old man returned to the rear companies.

Seated among the taller kains, Kurelu looks shrunken and obscure. The scars of an ancient fire burn have pinched his chest, and his dress is old and brown and simple. His face is intelligent and reflective, almost shy, and its power is not readily perceived. But Kurelu’s gentle smile is private, and his eyes are cold and deep, like small holes leading to infinity.

Each little while a wounded man was carried back. One of these was Ekitamalek of the Kosi-Alua, with an arrow in the breast. Ekitamalek would die. The battle flew back and forth until, toward midafternoon, another long lull occurred. An hour passed, and the warriors of the far villages started off in single file for home. But on an instant fighting broke out again. It was led this time by Weaklekek, who was a war kain of the clan Alua and one of the great warriors: Weaklekek, with his broad brow and mighty grin, was presently in mild disgrace, having missed a fine chance in the last war to kill a Wittaia with his spear. As it was, he had found himself cut off and was saved at the last moment only by a wild foray and flurry of arrows shot by two of his men.

A number of warriors had now been wounded, but no one had been killed on either side, and the fighting continued until dusk. The warriors whooped and ducked and came up grinning in an access of nervous ferocity, much like the boys with their grass spears on the homeward paths of twilight.

The four wives owned by U-mue do not all live in Wuperainma, partly because one or more must tend his pigs up on the mountain, and partly because Hugunaro and Ekapuwe fill the village with their fighting. In consequence, Ekapuwe, who is pregnant, has been sent to the pig village of Lokoparek, while the other three work in their husband’s fields.

The four wives owned by U-mue do not all live in Wuperainma, partly because one or more must tend his pigs up on the mountain, and partly because Hugunaro and Ekapuwe fill the village with their fighting. In consequence, Ekapuwe, who is pregnant, has been sent to the pig village of Lokoparek, while the other three work in their husband’s fields.

U-mue’s wives and their small children share two conical huts called ebeais. The ebeai, or woman’s round house, is perhaps ten feet in diameter and eight feet high. The lower floor is built a foot or so above the ground, and the sleeping loft about four feet above that: the loft is entered through a square hole in the ceiling. Both floors are carpeted with grass straw but are otherwise unfurnished. In the center of the ground floor is a hearth, which is delimited by four wood uprights at its corners. The uprights, which help support the ceiling, also prevent people from rolling into the fire: this a common accident among small children, and many akuni bear the scars of it, including Kurelu himself. The smoke of the fire must escape through a small doorway giving on the yard; outside the doorway, under the hanging fringe of the thatch roof, is a small area where two people, one on each side, may squat out of the rain.

The ebeais of U-mue’s wives are two of five in the long yard: two others belong to Loliluk, and one to Ekali. Across from the row of ebeais is the communal cooking house, an airy rectangular shed with a peaked roof of thatch and several doorways; though only six feet wide, it is over sixty feet in length, with three supporting posts from ground to ridgepole. The smoke escapes it through doorways, walls, and roof, rising with the steam of the wet thatch to mingle with the ground clouds of early morning.

Hugunaro crossed from her hut at daylight to prepare her fires. Morning hiperi—hiperi, or sweet potato, is the basic food, so much so that hiperi nan, the “hiperi-eating,” is synonymous with “meal”—are roasted at the fire’s edge, and the children are sent with them eventually to the men’s pilai, a communal hut like a very large ebeai which stands at the head of the yard, opposite the entrance: the men ordinarily rise later than the women and remain in the pilai by the hearth until the sun is well up from behind the cliff and the dank morning chill abated.

Their meal finished, Hugunaro sent her daughter with the other children to tend the pigs, which dwell in low sheds divided into separate stalls: the pig sheds may open into the rear wall of an ebeai, with the nearest stall reserved for piglets or sick animals in need of special care, but in U-mue’s yard the two sheds are separate structures in protected corners, with one end of each facing directly on the yard. Each yard normally contains one pilai and one cooking shed, five or six ebeais, and one or more pig sheds, depending on the prosperity of the inhabitants, all of these facing on a common ground and surrounded by a fence of palings; the village fences, as well as those surrounding outer gardens, are crested invariably with straw, designed to protect the raw fence wood from rot. Small plots or borders of tobacco, sugar cane, gourds, ginger, and other special plants are kept within the fence, where they may be guarded.

The entire enclosure, with its own entrance from outside, is called a sili. Sometimes an entrance is boarded up and the fencing between two silis taken down, establishing a common yard; in this case there are usually two pilais and two cooking sheds, with a corresponding increase in the dwellings of pigs and women. A village may be composed of one or more silis, depending on its age and its importance, though there are rarely more than three. Wuperainma, an important village, can boast four, but one of these is presently abandoned. As is often the case, the fence of the abandoned sili has been maintained, and the grounds have been turned to small garden plots as well as a grove of banana trees. Bananas are also grown, sometimes in company with pandanus, in weedy corners between silis, which tend to be erratic in their alignment. The warm green of the great banana fronds, wavering on the colder greens of the mid-mountain landscape, may signal the presence of a village even when the gold thatching of the roofs is quite obscured.

The sun had burned away the mists, and the men had left for the lookout towers to mount guard; Hugunaro, with the other women living in the sili, went out into the fields. Aneake, the birdy old mother of U-mue and Yeke Asuk, usually goes also, but today she remained about the cooking shed, tending the piglets and the smallest children. Frequently these children accompany their mothers: they sit astride the women’s shoulders, clinging to their hair. Infants are always borne this way, while new babies are carried in the bottoms of the nets extending down the mothers’ backs: here in the dark folds, except when taken to the breast, they ruminate all day.

The nets are a series of overlapping bags, woven from brown fiber of an aquilaria bush, and decorated usually, though not always, with V patterns of dark red and purple dyes. They are attached by a headband at the forehead, and swing freely down the back, over the hips; a full load may and often does include a cargo of vegetables at the shoulder blades, a small pig upside down toward the middle of the back, and a small baby in the deepest net, jouncing along on the behind.

Empty or full, the nets are worn at all times by the women, though they are not an article of dress. The women’s clothing is a sort of skirt of fiber coils which circles the body well below the waist; it passes under the bare buttocks, sweeps upward to cross the hipbones, and dips down again under the belly in a kind of scanty pelvic apron. The coils are slung loosely except at the hipbones, where they are tightly bound together; it is the pressure here which just maintains an otherwise precarious arrangement. The new coils may be very pretty, for a gray base of palm fiber is overlaid with the hard shiny inner bark of two woody ground orchids, one with red blossoms and red fiber and the other with purple blossoms and a fiber of bright yellow. The women’s skirts are woven by the men, who are the artisans of the akuni.

In the morning the nets are empty, swaying gracefully on the women’s backs.

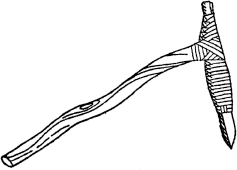

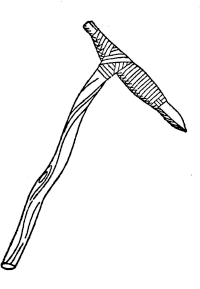

Hugunaro and the others walked in single file down through a wood of small trees and across the brook and out through the savanna to the ditches and the sweet-potato fields. A fairy-wren, a tiny scrap of black with bright white shoulders, chased another through yellow pastels of rhododendron. Each woman carried her digging stick across her shoulders and behind her neck, both hands raised to clutch it. The digging stick—the large oarlike stick used by the men and the smaller pointed one used by the women—is the only garden tool of the akuni.

U-mue’s fields are far away toward the Tokolik, and the file of women angled back and forth along the path, which zigzags out among the ditches; the drainage ditches, which are crossed by bridges in the form of slim poles, serve also to deter the pigs from ravaging the gardens. Hugunaro carried a tight bundle of grass thatch containing fire: the fires are used throughout the day to burn dried garden trash. Arriving, she laid this on the ground and built it up with dry weeds and vegetable detritus. Each woman then took fire to the area which she was working.

Hugunaro began immediately, using her digging stick with sharp backhand strokes, like paddling, to slash the weeds; later she would break the ground in the same way. Her digging stick is about five feet long, pointed sharply at both ends; it is known as the hiperi spear, for it must serve also as a weapon in the event that the women are attacked. Though their spears would be no match for those of Wittaia raiders, the women in concert might defend themselves just long enough for help to reach them from the kaios.

The smoke rose slowly from the fires, and all across the gardens, on both sides, small white plumes broke the dark patterns of the fields. It was midmorning. In midafternoon the men would take up their spears and move back toward the villages, and the women would go too. There were only two meals in the day, in the morning and the evening, and the hiperi must now be cooked, for dark would come in a few hours. The women would take the vegetables harvested that day and load them into their nets, so that, trudging homeward, they looked twice the bulk of the skinny creatures who had gone out in the morning.

Hugunaro’s figure is typical of the women, who, except when pregnant, are little fatter than the men. She is perhaps five feet tall, with small shoulders and full breasts, small hips, and short, thin, childish legs: these legs, which are characteristic, seem curiously out of place on female bodies otherwise well made. She is a pretty woman, with bright brown eyes and a quick mouth and a wry, strident manner; in her stridence and quick temper she resembles the pregnant wife, Ekapuwe, which accounts in part for their mutual ill feeling.

Koalaro is older than the other wives and without fire: she is of the mood and color of bare earth. The young wife, Yuli, has no child as yet, though she looks strong and willing. She is taller than the rest, high in the breasts and heavy in the legs and hips, for her labors have not shrunk her to muscle. Yuli has tight little eyes in a large and stupid face, and her loose smile is playful. She looks as if she had a secret, and indeed she may: not long ago she was seized while in the fields and taken away to their own village by some men of the Kosi-Alua. After three days she came back of her own accord, and while it is assumed that she was not raped, and even that no intercourse took place, U-mue is nonetheless very angry with the Kosi-Alua and plans revenge.

In the evening fields below the grove of araucaria, a man with a black dog was hunting a tiny quail. The dog, sharp-eared and bushy-tailed, was quick and small; it came with the akuni long ago and is peculiar to the highlands.

In the evening fields below the grove of araucaria, a man with a black dog was hunting a tiny quail. The dog, sharp-eared and bushy-tailed, was quick and small; it came with the akuni long ago and is peculiar to the highlands.

The man, carrying a throwing stick, followed the dog. His arm was cocked. There were four boys with him, the fleet yegerek of seven to fourteen, not yet warriors and no longer children, the scouts and messengers, the swineherds and the carriers of weapons; the yegerek were armed with short sticks of their own. The dog pounced, and a quail flew. The place was surrounded, and two more quail flew out, the low sun gleaming through their wings as they whirred down the savanna. None were struck down, and the group trotted onward.

The boys soon tired of the hunt. They broke off small spears of a firm grass and staged a war, dancing and feinting with the spears, and whooping, before darting forward to throw, wrists quick as snakes. In the dusk their thin bodies were no more than silhouettes, outlined against the distant hill called Siobara.

The warrior Yeke Asuk of Wuperainma got his name when still a boy. Yeke Asuk means “Dog Ear” and refers to a gift for overhearing word of any activity which might lead to trouble, such as raid or pig-theft, and tagging along behind. Yeke Asuk, volatile and hot-tempered and a sulker, has not lost his taste for trouble and is often, these days, at the root of it. But, as U-mue’s younger brother, he has influence, and he is brave.

The warrior Yeke Asuk of Wuperainma got his name when still a boy. Yeke Asuk means “Dog Ear” and refers to a gift for overhearing word of any activity which might lead to trouble, such as raid or pig-theft, and tagging along behind. Yeke Asuk, volatile and hot-tempered and a sulker, has not lost his taste for trouble and is often, these days, at the root of it. But, as U-mue’s younger brother, he has influence, and he is brave.

Two days before, on the Tokolik, Yeke Asuk had received a scalp wound from an arrow. The wound was superficial and no longer bothered him, and he sat with the other men around the hearth in U-mue’s pilai until the sun was high over the cliff behind the village. U-mue himself had been absent since the night before, on a visit to his pregnant wife up in the mountains.

Each morning, when their sweet potatoes had been eaten, the men smoked and talked in the dense warmth of the hut, and performed slow, peaceful work of manufacture and repair. Several worked together in repairing a shell bib: the shell strings lay coiled on a large leaf, and next to the leaf lay a supply of fiber from the spiny bamboo as well as some soft aquilaria. The aquilaria was woven across strands of bamboo to make the tough bands on which the rows of snail shells would be sewn.

In the sleeping loft above, Ekali turned softly. The ceiling of thin bamboo shafts supported by crossbeams of wood creaked vaguely with his movements. Soon a leg appeared out of the ceiling hole; it probed blindly for the wooden step which, polished with long use of callused feet, gleamed in the pale light through the doorway.

Ekali took a place behind the other men, who squatted near the door to use the light. At the hearth, as well as in the loft above, one is closer to the front according to one’s status—in a crowded hut, the kepu men and younger boys move to the rear. A tall, smiling man with a confident air, Ekali is kepu, but the others greeted him politely, their soft voices passing around the circle. Ekali, narak-a-laok, they said, taking his hand. Narak, narak. From the shed adjoining came the bumping of U-mue’s pigs, the consternation of each morning’s meeting with the children.

Yonokma is an older boy, an elege, sixteen or seventeen; he took from the wall an arrow shaft of cane and fitted it with a long tip, but the binding of vine needed repair, and Yonokma, with the shiftlessness of his age, replaced the arrow without really working on it. As the young brother of U-mue’s wife Koalaro, Yonokma stays frequently in this pilai. Because his movements are indefinite—he stays as often at his father’s pilai in Abulopak—his name signifies “the Wanderer.”

Yonokma’s friend Siloba began to sing. Siloba comes from the village of Mapiatma, on the far side of the wood, but he usually sleeps in Wuperainma, for U-mue is his nami. All akuni have namis, or men favorably disposed toward them in a protective and generous way; the nami is most often the child’s maternal uncle, though the relationship is not automatic, and a boy may have more namis than one. The nami relationship is the warmest of all family ties. A child will also have ceremonial fathers—the brothers, often, of his real father. Such a father would claim Siloba—An-meke, he would say, Mine, grasping his horim—with as much authority as Siloba’s own parent, and, in fact, the distinction between true and ceremonial is thought quite unimportant—in a sense, the head of the clan is the father of all in it. The ceremonial father, like the real one, is apt to be remote and strict, while the nami is indulgent.

As a house of warriors—in addition to Yeke Asuk, there are Hanumoak and Loliluk, and the boy Yonokma is already a fierce fighter—the pilai is stocked heavily with arrows and bows, with an arsenal of spare bowstrings, bindings, and new arrow points. The latter objects are wrapped in neat packets of straw or banana leaves and stored in the rafters or hung along the walls. Bundles of feathers, packets of fibers, a gourd calabash containing small fetish objects, a net bag of tobacco, some stone adzes, a bird-of-paradise headdress belonging to Hanumoak, some spare horims, and a men’s digging stick are stacked or hung against the walls toward the rear. Attached to the fire frame, near the ceiling, are a set of boar’s tusks for the nostrils, a boar’s-tusk knife, a cane mouth harp, and Yeke Asuk’s armlets of brown dog fur. By the side of the fire, which was now reduced to embers, lay long bamboo holders for the tobacco, and a small wooden tongs. The tobacco, wrapped and smoked in a coarse leaf, is called hanum; Hanumoak, “Tobacco Bone,” is named after the holder.

The sun had pierced the mist at last and gleamed in the puddles in the yard. One by one, the men left the dense warmth of the hut. Taking their spears—the spears are too long to be brought into the pilai, and are kept outside—they wandered toward the entrance of the sili.

U-mue’s wife Hugunaro, squatting in a doorway of the cooking shed, watched the departure without interest, for she watched it every morning of her life. As Siloba slipped past her, Hugunaro hissed at him. Siloba, she said softly. She beckoned him with the characteristic gesture, arm extended, palm down, folding her fingers down and back, down and back. E-me, eme. Come. She handed him a blackened hiperi. Siloba smiled, a quick, shy smile of thanks.

The warriors went down through the wood and out across the fields toward U-mue’s kaio. The path angled back and forth among the dark green leaves and violet trumpet flowers of the sweet potatoes. Every little while it crossed one of the drainage ditches, from which a coarse calla lily erected its large stalks; the corm of this lily supplies the vegetable of Oceania known as taro. Beside the taro plant floated leaves of its wild relative, a small water lily. Orange dragonflies zipped up and down the ditches, clashing in mid-air with a small dry, harsh electric sound, or poising suddenly on a leaf, their long transparent wings cocked forward. Like the drab mountain swiftlet which coursed the air above them, they were hunting insects.

U-mue had come down from the mountains and was already at the kaio. He wore a new crown of white feathers, taken from the wing linings of the black duck; the quills had been punched through a strip of papery pandanus bark to form a crown. Ordinarily the men do not wear such decorations to the kaio, but the crown was a new one and U-mue is vain. To go with the crown, he wore his large mikak and fine shell bib, with a string of cowries hanging down his back. A fresh band of black grease was drawn across his face, and his brow was also greased and shiny. Otherwise his dark skin was clean; he habitually looks cleaner than the other men, who do not always remove the fine gray scale of their own grime, nor the mud flecks on their lower legs. With U-mue was Apeore of Lokoparek, a taut-faced warrior with cold browless eyes.

The men crept beneath the shelter and hunched around the fire. On most days they would have rested here all morning, but today there was men’s garden work: though the women tend the gardens, the men do all the heavy work of creating and rebuilding fields and ditches.

Soon all but U-mue left the shelter. They had on the short horims worn at work, and the few wearing shell bibs turned these around so that they hung down behind. In a ditch a hundred yards away other men had already collected, standing in water over their knees. They reached down and dug double handfuls of mud and threw these up upon the banks, where older men packed the mud around each hiperi plant. Soon nearly twenty were splashing in the ditch, heaving and sweating. Hanumoak, who is quick-witted and handsome, paused for a while to daub some gray clay on his shoulders; he craned his head around, taking pleasure in his own appearance. The lame man Aloro came along after a while: he planted his spear butt in the earth and, sidling clumsily, joined the others in the ditch. Aloro was greeted with deference, for despite his twisted leg he is a fanatic warrior; it was Aloro who, with Yeke Asuk, saved the life of the war kain Weaklekek when the latter was cut off by the enemy. Though both Aloro and Yeke Asuk are young warriors, they have each killed two.

Beyond the men rose a pall of women’s fires. This morning the women had avoided the garden where the men labored, for though a man works sometimes with his wives, the two sexes never mix in larger groups. Once in a while the women, in apparent approval of the spectacle in the ditch, would laugh loudly among themselves, for in their cheerful way they are in league against the men.

U-mue climbed slowly and sedately to the top of the kaio tower and sat himself upon the platform, his feathers gleaming as he turned his head against the sky. U-mue was worried about his new crown, for though many of the people broke the taboo, the use of the wild duck in any way was considered wisa. Certain plants, animals, acts, localities, and other phenomena were wisa—invested, that is, with supernatural power. A wisa thing was not necessarily good or bad, but neither was it to be trifled with without due ceremony.

U-mue knew that the great kain Wereklowe, for one, had been angered by his use of duck feathers. A man who touched this bird, according to Wereklowe, lost much of the keenness of his sight and would thus be unable to spy out a raiding party of the enemy.

Just south of the village of Homaklep a small spur of the mountain, in the form of a low wooded ridge, slides out onto the valley floor and disappears. The village of Abukumo, half deserted now, lies on this ridge, and below Abukumo is a small wood. The wood gives on a grassy knoll, with a small grove of trees shading gray boulders; the knoll is called Anelarok. Below the south flank of Anelarok flows a small brushy stream, the Tabara, and to the west lie the open grasslands and the gardens.

Just south of the village of Homaklep a small spur of the mountain, in the form of a low wooded ridge, slides out onto the valley floor and disappears. The village of Abukumo, half deserted now, lies on this ridge, and below Abukumo is a small wood. The wood gives on a grassy knoll, with a small grove of trees shading gray boulders; the knoll is called Anelarok. Below the south flank of Anelarok flows a small brushy stream, the Tabara, and to the west lie the open grasslands and the gardens.

Anelarok lies at a crossing of the paths, and because it commands a fine view of the valley there are often people, and a fire. The paths lead from the villages to the Aike, and from the fields into the mountains; the least-used is the one which plunges down into the undergrowth of the Tabara, crosses the stream on large flat stones, and climbs again on a steep slope toward the land of the Siep-Kosi. This path was used one afternoon to take a wounded Siep-Kosi home to his own country.

In former times the Siep peoples fought separately with both Wittaia and Kurelu, and though this practice proved too costly, their warriors still wished to go to war. The tribe divided into factions, one of which—the Siep-Elortak—fought henceforth at the side of the Wittaia, and the other—the Siep-Kosi—at the side of the Kurelu. This warrior had been wounded in the upper chest, fighting on the Tokolik. Too seriously hurt to be carried across the hills, he had lain for many days in Mapiatma. Then one day his people came for him and took him home.

Two poles were lashed parallel with vines, and the man was slung between them, supported under the arms and knees. His body was swathed in leaves and lashed securely; even his head was covered, leaving him just air enough to breathe. He was borne by seven men across the fields in front of Homuak, down through the woods, and up over the knoll of Anelarok. The journey homeward was a long one, but the men did not pause at Anelarok to smoke. Some Kurelu were there, and a fire burning, but the Siep-Kosi passed through quickly. The Kurelu and the Siep-Kosi, enemies in the past, could readily become enemies again.

The stretcher jolted down across the Tabara and climbed again on the far side. The paths were steep and rocky and slippery with the rains, and the seven bearers struggled with their load. The man sat still as a green mummy, as if he were long dead. Only once, when the caravan faltered, high on the far slope, did a slow hand rise toward the green head, hover a moment, and drop away again. The bearers moved onward, picking their way toward a sky gray with coming rain, until the figures were as small as ants hauling a dead cricket.

The journey was watched from the kaios of the Kurelu. The men at the kaios knew about the journey, as the akuni know of all things in their world. An event in the lives of the Kurelu is known as fast as a boy can run the ditch logs with the news, but no boy is ever sent. The word bounds straight across the fields like the flight of the brown finches, from village to path to garden—the men’s heads turn in the shadow of the shelters, the women straighten to rest a moment on their sticks—in a series of small whoops as pure and unmistakable as the flight signals of the birds. The people know the course of things, for the course of things may be thousands of years old, and all they really need to hear is the one word which changes; the event does not. The man’s name is called, with the high whoop which relays it onward.

The wounded man had come of his own accord because he wished to fight, and he was wounded because he was too brave or too careless, or because the power held in the holy stones of his people had not worked for him. This too was in the course of things. The Kurelu would be sorry if he died, and they would weep because weeping was expected, but a large part of the sorrow would be brought about by the satisfaction given the Wittaia. The Wittaia knew about this warrior, in the same way that they knew about each enemy struck in the body: they knew his name and village and his clan, and they hoped that he would die. But it now seemed that he was going to live, and in a short time they would know this too.

In the morning, when the sun appeared over the valley, the warriors trotted along beneath the mountain, bound for the northern wars. Among those who did not go was Yeke Asuk. He was not quite recovered from the head wound suffered on the Tokolik, and he had private business to attend to.

In the morning, when the sun appeared over the valley, the warriors trotted along beneath the mountain, bound for the northern wars. Among those who did not go was Yeke Asuk. He was not quite recovered from the head wound suffered on the Tokolik, and he had private business to attend to.

Some time ago a man from a village in the northern Kurelu had trespassed in his gardens. This is a most serious offense, and Yeke Asuk had stolen three of the man’s pigs in compensation. Two of the pigs had been speedily consumed, but recently the third had been restolen by its owner.

To redress this outrage, Yeke Asuk traveled to the village to demand the pig’s return. He was accompanied by his friend Tegearek, a violent man who shares with the lame man Aloro the war leadership of the clan Wilil. The color of both Yeke Asuk and Tegearek is golden-brown, markedly lighter than the average though by no means unique, and as both are also very short and powerful, they made, as they set off, a distinctive pair.

Yeke Asuk, less than five feet, is probably the shortest of male akuni. Limo, a kain man of the Kosi-Alua, is among the tallest. Limo is probably five feet nine, but his small shoulders and lithe body, more typical than the stumpy shape of Yeke Asuk and Tegearek, make him appear well over six feet tall. Many other warriors seem taller than their height: this is especially true when they are holding, as they often are, spears three times their own length.

The pig was not returned to Yeke Asuk, and, as circumstances did not encourage either seizure or re-theft, he and Tegearek went home. The complaint had been registered, to justify in advance any action that might be taken afterward. There was, in the valley, all the world and time.

Uwar and Aku came down along the wooded ridges, carrying on their heads bundles of fagots for the sili fires. When the steep slope fell away toward Wuperainma, they rolled the fagots down the hill, and the bundles leapt and sprang through the green hill shrub, starting the yellow white-eyes and quick wrens from their low shade.

Uwar and Aku came down along the wooded ridges, carrying on their heads bundles of fagots for the sili fires. When the steep slope fell away toward Wuperainma, they rolled the fagots down the hill, and the bundles leapt and sprang through the green hill shrub, starting the yellow white-eyes and quick wrens from their low shade.

The children, black motes on the white cumulus, strayed on the afternoon’s high horizon, sad to descend out of the sky. From where they stood their whole world and their whole life lay before them, all the northeast corner of the valley. The Elokera slid away beneath their feet, forsaking the mountain near the village of Takulovok, which lay invisible under the crest. The river entered a woodland of albizzia and emerged a slow brown grassland stream, unwinding along the mountain wall. Then it curled off westward, through the Kosi-Alua and the Wittaia, to come to an end in the smoke-misted distance, the Baliem.

The Baliem lay in the countries of the enemy, and though it was less than four miles distant, at the far end of the Siobara, the children would never know more of it than the fringe of casuarina which hid its waters from their sight.

Above the children’s heads three brown hawks circled, shrieking in tight, ratchety vexation in the high blue day. Other birds came rarely to the crest, which was no more than a jagged outcropping of limestone karst, heaved up out of the sea in other ages. Lichen and bracken ferns clung to sparse soil, with dwarf shrubbery in the niches, but songbirds rarely paused there; the insects were scarce, and the dry lizards stayed away. Only the hawks came, riding the updrafts from the valley warmth, and the fierce blue-gray hunter of all continents, the peregrine: the falcon dove down the steep hill like a shard of falling sky, its passage booming a half-mile away.

Below the hill, on the south side, was their own village of Wuperainma: Uwar is the son of Loliluk and Aku the daughter of U-mue. The children could spy down on the silis and watch Aku’s grandmother, Aneake, pick her way along the cooking shed. This was the still time of the afternoon, when all the people were in the fields; Aneake was too old to work steadily in the fields and rarely left the village now except to hunch in the near weeds or gather twigs.

They came down slowly, caught in the grave immobility of time, the sun and grass; the crests of the araucarias which shaded the spring of Homuak were still far beneath their feet. Now they could see Abulopak, the bare yards gleaming through the pale green of banana trees, backed up against the hill’s northwestern flank. Between the children and the villages, the slope was broken by round limestone sinkholes, and in one of the holes the wall sheltered a grotto; there was a fireplace, and long ago, before the children had first gone there, akuni had drawn pictures on the wall. Almost everywhere that people had sheltered beneath a rock and built a fire, such drawings had been made. They were made still, with charcoal sticks, for no other purpose than the amusement of the artist, for there was no language of symbol. There were men and women on the soft, pale stone, and a large crayfish, and some lizards.

The children sprang down the grassy hillside, quick as black dancers. Their voices called out to the people passing on the trails below, but the voices came from another world and went unanswered. Uwar sang vaguely, sadly, without sadness, and the song wandered on the airs of afternoon.

Early in the morning, when the pigs of U-mue’s sili are herded out into the fields, they are apt to consort briefly with a herd from the sili adjoining. The animals of U-mue’s sili are tended in rotation by the numerous children, while those of the sili of Asok-meke are tended invariably by Asok-meke’s stepson, Tukum.

Early in the morning, when the pigs of U-mue’s sili are herded out into the fields, they are apt to consort briefly with a herd from the sili adjoining. The animals of U-mue’s sili are tended in rotation by the numerous children, while those of the sili of Asok-meke are tended invariably by Asok-meke’s stepson, Tukum.

Like all the swineherds in the Kurelu, Tukum conducts his pigs each morning to a predetermined pasture, usually a sweet-potato field gone fallow. Here the pigs eat greens and the stray vegetables which have escaped the harvest, and root for grubs and mice and frogs and the small skinks along old ditches. In the afternoon he escorts them back to village pens, where they are fed hiperi skins and other offal from the fires. Each pig is marked almost from birth for a certain fate—a ceremony, a marriage gift, the payment of a debt—but until the day of its demise it leads an orderly and pleasant life, prized and honored on all sides.

Despite the great worth of the pigs and the prestige they bear, little husbandry is practiced, though piglets, very small or ailing, are usually carried in the women’s nets and receive special attention. Should a sow reach breeding age, she may be escorted to a noted boar, lest one of her own scraggy kin should work his way with her. The daytime haunts of these illustrious boars, like the haunts of every animal in the villages, are common knowledge, and, while permission may sometimes be asked of the boar’s owner, the decision is more often left to the stern animal itself.

As Tukum is thought of as incompetent, even for a child of seven, such a delicate matter as sow-breeding would probably be left to his mother. Tukum’s mother is a shrill, cheerful woman, the gap-toothed bane of her young son’s existence, who, with her infernal pigs and her incessant shouting, reduces Tukum almost daily to bitter tears. Not only is Tukum smaller than the children of U-mue’s sili but his pigs are larger. The pigs take advantage of Tukum’s forgetful nature by losing themselves in the low wood or barging into gardens where they do not belong, and as they are far stronger, better coordinated, more numerous, and more intent than he, they make of his days a series of small emergencies. His only weapon is an extraordinary voice, both loud and gruff, and hoarse with use, which signals the presence of Tukum and his charges from great distances away.

Ekapuwe lives presently in the hill village of Lokoparek because she cannot abide Hugunaro. According to Ekapuwe, her rivalry with and dislike for Hugunaro was born of U-mue’s insane love for Ekapuwe, on the one hand, and Hugunaro’s disgusting jealousy on the other.

Ekapuwe lives presently in the hill village of Lokoparek because she cannot abide Hugunaro. According to Ekapuwe, her rivalry with and dislike for Hugunaro was born of U-mue’s insane love for Ekapuwe, on the one hand, and Hugunaro’s disgusting jealousy on the other.

Ekapuwe is a Wittaia woman, married formerly to a Wittaia. In those days, perhaps seven years ago, the Kurelu were at war not only with the Wittaia but with those Siep-Kosi who are their neighbors to the southeast; the region of the upper slopes where Lokoparek now lies was then wild forest, a part of the frontier no man’s land.

One day Ekapuwe and her husband came to the forest to gather fiber, and there the beautiful Ekapuwe was spied by U-mue. It came to U-mue on that instant that he must have this woman above all things in life; at the same time, he was not prepared to attack her husband single-handed. The love-stricken man ran down the mountain to summon reinforcements, and returned not long thereafter with a well-armed band. Ekapuwe’s husband was driven off, and Ekapuwe herself became the prize of U-mue.

The romantic tale of Ekapuwe and U-mue is anathema to Hugunaro. Her terrible jealousy, in Ekapuwe’s opinion, makes the idea that U-mue should sleep with other women unbearable to Hugunaro, and it is for this reason that she resorts to an abortionist, for otherwise U-mue might neglect her in time of pregnancy. Hugunaro has made a habit of having herself aborted, four or five times, it is said. The abortion is effected by certain skillful women using techniques of pummeling and massage; the fetus is dropped in a special pool in the small stream called Tabara. Among noted abortionists is Asok-meke’s wife, mother of Tukum the swineherd. While abortion is more or less accepted among unmarried girls—as most girls are wed within a year or so of puberty, the event is rare—it is frowned upon when practiced by married women, and the likelihood is that U-mue and Hugunaro have quarreled on this account. On the other hand, the husbands are rather ignorant about abortions; there is a song of the akuni in which the women gloat over their husbands’ innocence,—but we, the women, know the truth! Many women dislike having children, and abortion is quite common.

It was the passionate Hugunaro who gave her husband the mildly derisive name that he now bears—the name U-mue means “the Anxious One.” With his intrigues and maneuverings, U-mue has every reason to be anxious, and a group of wives which includes, besides the rivals, a big, sleepy girl like Yuli cannot add very much to the Anxious One’s peace of mind.

When a man enters a sili which is not his own, his spear is left against a tree outside; otherwise, he rarely goes without it. The cheerfulness, even gaiety, of the people is the more remarkable for the fact that never in the whole course of their lives can they be certain that death does not await them down the path; after each peril, like the small mice which dart or flatten in the grass at a hawk’s passage, they continue as though nothing had occurred. Nevertheless, a man travels armed, not only in the vicinity of the frontiers but on his home trails; quite apart from the enemy, he may need his spear in the disputes which occur constantly within the tribe itself.

When a man enters a sili which is not his own, his spear is left against a tree outside; otherwise, he rarely goes without it. The cheerfulness, even gaiety, of the people is the more remarkable for the fact that never in the whole course of their lives can they be certain that death does not await them down the path; after each peril, like the small mice which dart or flatten in the grass at a hawk’s passage, they continue as though nothing had occurred. Nevertheless, a man travels armed, not only in the vicinity of the frontiers but on his home trails; quite apart from the enemy, he may need his spear in the disputes which occur constantly within the tribe itself.

One fine day, down by the river, a man of the Kosi-Alua was badly injured, in part because he had left his spear at home. The wife of this man had left him for a man of the Siep-Kosi, and he had reason to believe that her flight had been assisted by Tegearek of Wuperainma. He came to question Tegearek, who denied all part in it, and when he came several times again, suggesting by his insistence that Tegearek had not told him the truth, the latter became woefully annoyed: whether or not the man’s suspicion was well founded, Tegearek felt himself insulted.

One morning the man came to the Aike, accompanied by several tribesmen; they were bound not for Wuperainma but for the lands of the Siep-Kosi, to inquire after the missing wife. The husband, foolishly unarmed, had wandered from his friends, and near the river he encountered Tegearek.

Tegearek is the young war kain of the Wilil, an innocent man of violence: his name derives from tege warek, or “Spear Death.” He is strong and stocky, with two black front teeth and the wistful expression of a man easily confused. He is hot-tempered in the way confused people often are, and he had with him Yeke Asuk, whose hot temper is more complex. These factors, in combination with the fact that his tormentor was alone and unarmed, persuaded Tegearek that an attack was timely and, after a brief and violent exchange, he launched it. No cowardice on Tegearek’s part was involved in this, for according to Dani codes a man who so forgets himself as to run afoul of an antagonist while unarmed and alone deserves no mercy and receives none.

Tegearek did not intend to kill the man but simply to punish him a little. To this end he jabbed him twice, once in the thigh and a second time in the head. His victim seized hold of the spear and tried to wrest it from Tegearek; when he managed to turn it in Tegearek’s direction, he was speared in the stomach by Yeke Asuk. Yeke Asuk did not wish to kill him either, and the spear was withdrawn after having penetrated two or three inches. The two friends left the man where he lay, not knowing how many Kosi-Alua might be along, or when they might appear.

The group of Kosi-Alua appeared soon after. They carried their friend home across the open fields, avoiding the brushy trails under the mountain. The wounded man sat astride the shoulders of each friend in turn, supported by two others at the arms. He was slumped, head hanging, and his head had been bandaged in vegetable leaves; in the sun, his back glistened with heavy sweat. The women straightened, watching in silence as the group made its way across the fields; it entered the brushland west of the dancing-field called Liberek and disappeared.

Since this episode Tegearek and Yeke Asuk have moved with caution, for they expect reprisal.

One morning on the way to his kaio, Weaklekek, the great warrior of the clan Alua, startled a large bird from the base of a rhododendron. The bird flew to the low limb of a chestnut tree overlooking the lower Tabara. Weaklekek took a hunting arrow from the bundle he carried with him and laid the rest in the grass; he ran silently down a slope on the far side of the tree, beyond the bird, and crept up on it through the bushes. The bird sat uneasily on the limb, a soft, rufous brown bird with a very long, wide tail. It was a mountain pigeon, the call of which, hoo-oik, hoo-oik, hollow and mournful, is imitated by the warriors in time of war. Weaklekek crept up too close, as he did not wish to waste his arrow. The bird flew as he raised his bow, and the arrow skittered across the empty branch.

One morning on the way to his kaio, Weaklekek, the great warrior of the clan Alua, startled a large bird from the base of a rhododendron. The bird flew to the low limb of a chestnut tree overlooking the lower Tabara. Weaklekek took a hunting arrow from the bundle he carried with him and laid the rest in the grass; he ran silently down a slope on the far side of the tree, beyond the bird, and crept up on it through the bushes. The bird sat uneasily on the limb, a soft, rufous brown bird with a very long, wide tail. It was a mountain pigeon, the call of which, hoo-oik, hoo-oik, hollow and mournful, is imitated by the warriors in time of war. Weaklekek crept up too close, as he did not wish to waste his arrow. The bird flew as he raised his bow, and the arrow skittered across the empty branch.

A man’s voice called to him, We-AK-le-kek, a-oo.

Weaklekek went on down toward the Aike, stepping over a tribe of biting ants which, oblivious of his feet, dragged a dazed grasshopper across his path and into the grass jungle. He was the first man at the kaio. Other men, bearing their spears, arrived in a few minutes, and Weaklekek left his kaio and went down into the gardens. His wife Lakaloklek and their daughter Eken were breaking up stale earth, turning and splitting the old lumps with hiperi spears. Weaklekek had the men’s digging stick, and he set rapidly to work, panting rhythmically and hoarsely from the start. Behind him the girl, whose name means “Seed” or “Flower,” burned the dried weeds, and a light air out of the east carried the smoke toward Weaklekek and shrouded him. With Lakaloklek, he surged and vanished in the fumes. Feet planted in the black-brown earth, the man and woman were the exact color of the soil, as if they had sprung out of the smoke and earth, like trolls. Weaklekek’s great strength and energy were of the earth, infusing him, as if one day he might leap free and climb the sky.

Except when in the act of love, in wayside grass or the night darkness of an ebeai, a man and wife are entirely undemonstrative; this is prudishness, not lack of warmth. Weaklekek and Lakaloklek are no exception. Nevertheless, and despite the fact that Weaklekek has other wives, he is plainly closest to Lakaloklek. Lakaloklek herself, a slim, spirited woman with a pretty, elfin face, took upon herself the disapproval of the community by rushing to Weaklekek immediately after the death of her first husband: her name means “She Who Would Not Wait.” More than any other man and wife in the southern Kurelu, they seem a pair. There is an air of strong communion when they are together, of wild and unarticulated tenderness.

Weaklekek worked relentlessly, his dark body gleaming in the pall. The dirt flew, tumbling in clods. From one clod wriggled a bronze ground lizard; it writhed down to the water of the ditch.

Weaklekek cried gleefully at the sight of it, for the fact of it. Some water spiders flew before the falling clods, and he called out softly, Pilili, pilili—Be quick, be quick. Behind him, Lakaloklek laughed, as affectionately as wives of the akuni ever laugh, but she did not cease working. She turned the earth slowly and steadily, bent over her stick, breasts swaying.

When Weaklekek first came to live in the southern Kurelu, he was called simply We-AK, which means “the Bad One.” He brought this name with him from the northern countries, where he had had a wife. One day, not long before he came to Homaklep, this wife told him that she had been raped by men of a near village, and Weaklekek went immediately to confront them. The men were absent, and Weaklekek, as was his right, seized a number of their pigs and took them back to his own sili.

The next day his wife confessed to him that she had not been raped at all; apparently she had lied to him in the simple hope of making trouble. Weaklekek has a dark temper, and he became enraged. Nevertheless, he retired into his pilai, attempting to control himself. Some hours later he emerged and, finding his wife before him in the yard, struck her a terrible blow along the jaw. She dropped senseless to the ground, and before the next morning she was dead.

Weaklekek was grief-stricken, for he had loved this wife; certainly he had not meant to kill her. He could not forgive himself for what he had done, and meanwhile his own life was in danger. Custom demanded that she be cremated, but her kinsmen were infuriated by her death and swore that they would kill Weaklekek; he could scarcely invite them to the funeral. Furthermore, he had no support from his own people, who were shocked by his act and would not go near him; they referred to him from that time forward as the Bad One.

It was characteristic of Weaklekek that he made no attempt to excuse himself, to mollify the akuni by inviting them to feed upon his pigs. On the morning following the death, when the funeral would ordinarily have occurred, Weaklekek went out into his yard. In a passion of grief and anger and remorse, he tore down the fences of his sili. All alone he hurled the laths together in a mighty pyre, and all alone he carried forward the body of his wife and laid it on the flames.

When this stark funeral was finished, Weaklekek left his village and walked off to the southward. There was no life left for him where he had lived, and he knew that sooner or later the kinsmen of his wife would try to kill him. He went to the village of Homaklep, on the far southern frontier, bringing with him a heavy heart and a bad name. Homaklep lay in the shadow of the enemy, and its people were glad to have a man such as Weaklekek, even though he was an outcast.

Not long thereafter his wife’s kinsmen ambushed Weaklekek along a trail. He killed one of her brothers with an arrow, fighting furiously—so furiously that the attack was never again repeated—but in doing so he worsened his own reputation. Nevertheless, in his new village he worked hard, earning respect, and became one of the great warriors of the region. Over the years, the name We-ak was lengthened to Weaklekek, to wipe away the sense of it, though the killing of his wife and her brother have maintained his reputation for violence.

The akuni still fear Weaklekek on those rare occasions when he loses his temper, and Weaklekek himself, despite his generosity and kindness, gives frequent sign that he is a burdened man. Always solitary, he retreats at times into a somber silence, as if in dread of his own strength. His broad back to the world, he hunches over a long shell belt, weaving, weaving.

Not long ago both wives of a man named Werene were raped in the fields by men of the Kosi-Alua. Werene stole two of their pigs, the normal compensation, and gave them to Weaklekek for safe keeping. But the Kosi men did not recognize his right, having small respect for Werene. They came to Homaklep and, failing to find the two animals in question, made off with Werene’s entire herd.

Not long ago both wives of a man named Werene were raped in the fields by men of the Kosi-Alua. Werene stole two of their pigs, the normal compensation, and gave them to Weaklekek for safe keeping. But the Kosi men did not recognize his right, having small respect for Werene. They came to Homaklep and, failing to find the two animals in question, made off with Werene’s entire herd.

A man suffers offenses according to his inability to defend himself, and Werene suffered both of the most common ones, which are pig-theft and wife-rape. In principle the offender is paid back in kind. Should he be found out—and as these acts are usually an expression of power, he is almost invariably found out—and should he accept the theft of his own pigs or the rape of his own wife, the matter is then closed. But more often the victim of the offense is chosen in advance for qualities of cowardice or impotence and suffers his injury to go unpunished.

The great kains, though wealthy in both pigs and women, are not often sinned against, for it is one of their prerogatives to kill a man, or his subordinates or children, when he has done them harm; indeed, the demonstrated willingness, and even eagerness, to take life is an important asset in establishing a great kainship in the first place. But a man who is totally kepu soon loses to stronger men any pigs he may have acquired, and his wives, when not raped, are taken outright. This is the law, and, should he resist it, he may die or be cast out.