ALICE WATCHED THE SKYLINE DARKEN in the distance. She kept her engine running. The engine was a next-gen hybrid and barely purred, mostly drawing juice at a low idle rather than torque from a loud engine. Still, the vehicle’s little sounds were a comfort, making her feel like she could floor it and be gone in a shot if she needed to.

The thought itself was tinged with liberal guilt. Alice had parked on a slight rise, in what passed for a low-rent park, and the surrounding area was mostly clear in all directions. Nobody — and nothing — could come for her without being seen, and that was doubly true because Alice had parked under a large halogen streetlight. Still, the idea that she’d taken precautions (the open parking spot, the light, the running engine) felt wrong. Alice Frank was supposed to be a crusader for human rights — even if the definition of human had changed in recent years. She was supposed to be fighting for the little guys on the bottom rung, casting a skeptical eye at the big boys. Alice had covered little other than Hemisphere since the first big outbreaks, since Bakersfield, since Rip Daddy had mutated into the far more troublesome Sherman Pope. That was supposed to make disenfranchised people of all stripes (but especially necrotics) her peeps. And, in theory, she should be their peeps, too.

And yet here she was, in the most densely necrotic part of town, her windows up, doors locked, engine running, jittering like a scared little white girl in the middle of the inner city.

She forced herself to lower her window. She’d see anyone before they could do anything to her anyway, and if she was politically incorrectly frightened of necrotic criminals, she had even less to worry about. In this part of town, victims often had real advantages over gunmen. It was hard for all but the newest necrotics to use firearms at all, they weren’t usually fast, and you couldn’t understand them anyway when they said, Gif me aww jor muddy, or I’ll thute.

The thought made Alice give a shameful, nervous laugh. The park was deserted, and her own snicker seemed to echo back as if off the wall of a handball court. Hearing it, thinking of necrotics playing handball, Alice laughed again. The new laugh echoed back harder in the twilight, and finally her bones seemed to chill. She pressed her lips tight.

Headlights appeared in the distance. Alice swallowed, gripped her steering wheel despite that ever-present guilt, and steeled herself. As the sky darkened and the sounds of night in the so-called Skin District started to chatter, an empty park wasn’t a place a healthy lady wanted to be alone. She’d flee if this wasn’t the person she’d come here to meet.

She couldn’t see the car’s cab until the headlights were eclipsed by her own car’s body. But then she saw the face inside and relaxed: a man in his thirties, face stubbled, hair combed in a way that was perhaps overly neat. He had bright-blue eyes just like the few photos she’d found online, and despite the circumstances, he managed a small, attractive smile in greeting.

His window went down. The two cars paused side by side with their fronts in opposite directions, open windows lined up.

“Did you have any trouble finding the place?” Alice asked.

Ian shook his head. “No. It came up in my GPS. I saw your headlights when I came in on the main service road. The gate was closed, but there was room to drive around on the grass.”

Alice nodded. “I didn’t know they closed it. I’ve only been here in the daytime.”

He swallowed. His Adam’s apple bobbed as Alice watched his profile. He didn’t want to say it any more than Alice had wanted to admit it to herself, but he was scared shitless. Maybe even more frightened than he’d sounded on the phone when he, for a change, had dialed her number.

“What made you call me?” she asked. He’d been so guarded on the line. Alice felt the same most of the time, but it was strange to see paranoia from someone who lived in Lion’s Gate. Ian wore suits to work and probably pulled in around a half-million dollars a year. Alice was used to speaking like her phones were bugged because they probably were. But Ian worked for Hemisphere. Strange that he’d suddenly become afraid they’d overhear him.

“Something is going on. I don’t know what it is, but it’s something.”

Alice wanted to make a sarcastic remark, but now wasn’t the time. He was here. He’d made contact. For now, she’d handle him with kid gloves if it kept him talking, grateful that her absurdly priced scrambler would destroy the dialogue for anyone who might be listening in.

“Did you learn something that … that changed your mind about talking to me?”

“Someone’s watching my house. I’ve been … called in.”

“When we were talking earlier. It sounded like someone grabbed you.”

Ian nodded.

“Why? Where did they take you?”

Ian’s eyes flicked around the park. “Not here.”

“Why not?” Alice looked toward the road, the direction Ian had come from. “Were you followed?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never been followed before. This isn’t something I’m used to. It’s not something I goddamn deserve!”

Alice let it go. She could see fear, frustration, anger. Ian wasn’t acting like a normal source. He was acting reluctant, as if he’d been dragged here. As if he didn’t particularly want to talk but found her to be the least of his pressing evils.

“It’s safe here. Nobody can hear.”

“It looks bad. What would I be doing in this part of town?”

“Checking in on all the good Hemisphere is doing.”

Ian shot her a look.

“Sorry. I make jokes when I’m nervous. You want to go somewhere else, we’ll go somewhere else. No problem.”

Ian was still looking around. In the distance was a playground that looked a bit sad in the daylight but managed to look menacing in the dark. It was all plastic, all padded, all totally necrotic safe for the little dead children. The city had erected the park two years ago as a grand gesture then forgotten it. Locals had taken it over, some good, some bad. This section had grown decrepit in just two years but was the safest of the lot. There were hideaways among the wooded sections where people traded lost body parts. Not for use. Just for fun.

“No. It’s fine. I’m just … I don’t like any of this. I didn’t ask for it.”

“You’re doing the right thing.”

Ian’s eyes became momentarily hard, shadowed under the reflected glow from the overhead light. “I’m doing the only thing I can. I’m not trying to be noble. To be honest, I’m not convinced you’re not behind more of it than you’re admitting.”

Alice decided her best chance was to attack the accusation head on. “Understandable. But you called. You came. So you must believe me on some level. What changed your mind?”

“I saw that it wasn’t you staking out my house. It was men. Two of them.”

“Maybe they’re my cohorts.”

“They have Panacea plates.”

“Panacea?”

“You know who else has Panacea plates, just for the permissions?”

“You think the people outside your house are Hemisphere?”

“One or the other. But not just anyone at Hemisphere. I have normal North Carolina plates. But I’ve seen the lines blur before.”

Alice had heard rumors that confirmed what Ian was implying — that Hemisphere and Panacea worked together more closely than was commonly accepted — but it seemed too early in their relationship to be too bold.

“Why do you think they’re watching you?”

Ian half scowled. “I don’t know.” Then he told her a story very like her own: an anonymous source who gave hints but never any real information, nudges from this direction and that without any real help, even a response from Archibald Burgess himself that made Ian’s paranoia about being stalked feel valid. To Alice, Ian sounded like a pawn. He seemed to be suspecting Hemisphere plenty, but ironically the company seemed to have caused his suspicions itself. The Ian Keys she’d researched and tried to call earlier had sounded like a Boy Scout, loyal to the end. Now he sounded like a jilted lover. Someone whose dutiful affections had been upended one too many times.

“I think the same person has been leading me,” Alice said then gave him her own history, from the anonymous packet at her door to the way her phone had rung, finding herself voice to voice with Ian as if she’d placed the call herself.

But that reminded her of something, too.

“BioFuse,” Alice said.

Ian’s head flicked toward her.

“I got a message while we were talking. It said, ‘Ask him about BioFuse.’”

Ian’s eyebrows scrunched together. “What about it?”

“I don’t know. I got a pamphlet. A product brochure. And I looked it up online. Seems like it was one of Hemisphere’s earliest drugs, discontinued around the time Sherman Pope hit. Does that ring any bells?”

Ian shrugged. “It’s like you said. It was one of the lines Archibald believed in most. If not for the outbreak, we’d probably be in the BioFuse business today.”

“Curing Alzheimer’s,” said Alice. She’d had a grandmother who’d died mostly demented, unable to remember her own husband. Nana had gone before BioFuse would have hit prime time, but it felt like a worthy line of research to Alice, for other people’s sake. Maybe designer Necrophage (and international distribution of base Necrophage, just in case) was more lucrative than their dropped line, but letting it go felt almost offensive.

“It was one of a suite of drugs. Alzheimer’s, yes. But there were others.”

“Were the others discontinued?” Alice asked.

“I don’t know. I’d have to check.”

“Why was BioFuse discontinued?”

“I don’t know. It’s a company legend, but I don’t know the details.”

“Was it distributed? Did people take it, I mean?”

“Oh, sure. A lot of people, I think.”

“Wasn’t it profitable?”

“I assume it was, but again, I’d need to ask.”

“But other drugs like it remain in production?”

Ian nodded.

“Why just cut the one?”

“I don’t know a lot of details.”

“How did it work. Do you know? Was it a … ” Alice fluttered, wondering why she’d asked. She didn’t know the types of pharmaceuticals or what to do with any information he gave her. She was recording on the sly via the digital recorder in her pocket and could analyze anything said afterward (all of this was off the record anyway), but asking-wise, she was at a total loss. “A beta-blocker or something?” she finished, wondering why it could possibly matter. “What did it do to help Alzheimer’s patients?”

“I don’t know. I’m not a chemist.”

“You must know something.”

“I’m an executive. I work in an office. When I ask too many science questions, people look at me funny.”

“You’ve asked?”

Ian looked caught. But what the hell; he’d come here to talk of his own free will.

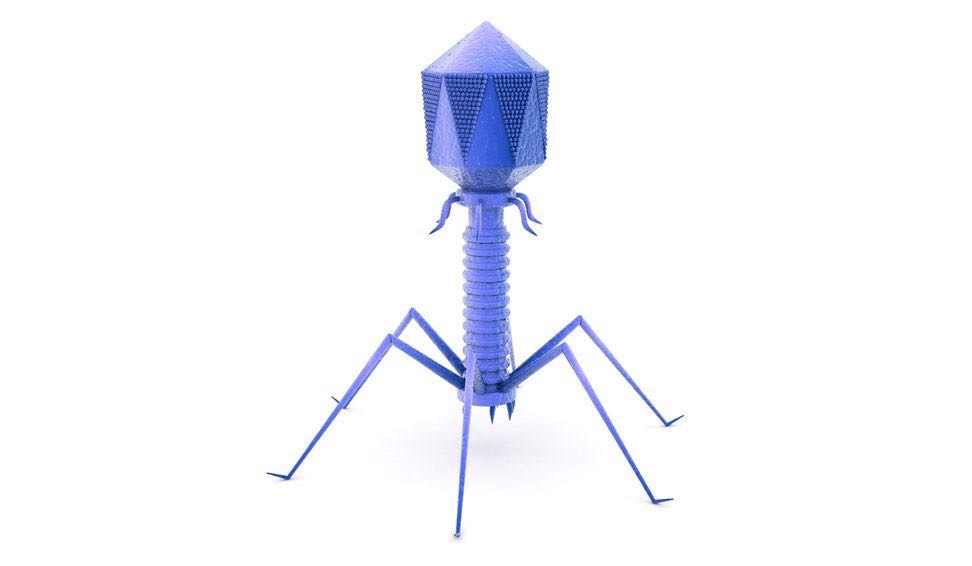

“One of the bits my anonymous tipster was pushing at me had to do with viruses. So yes, I asked.”

“What did you find out?”

“Nothing.”

“You must have learned something.”

“No, nothing!” Ian tipped his head back and peered at the ceiling, looking for all the world like a man resisting an outburst of temper. He looked back over. “I didn’t even know what to ask — virology was all I had. Shit, I don’t know about any of this. I was just sitting in my office, and someone started pushing shit at me. Stuff I didn’t understand. Told me to copy it, so I did. Told me to read it, so I did that, too. But none of it made sense. The stuff I could understand was all basic company information. Not even confidential.”

That sounded familiar. Whoever was playing Deep Throat for them both was inexplicably cagey. He or she seemed unwilling to come out and say what the hell either of them needed to know. Instead, they were being led on scavenger hunts that seemed to be on a collision course … with no useful results.

“All of it? It was all public?”

“What I could understand, yes.”

“What about the stuff you couldn’t understand?”

Ian looked back at Alice, seeming ready to shout and drive away. “I couldn’t understand it,” he said slowly, as if she were a late-stage necrotic, barely able to tie her shoes.

“Was it about BioFuse?”

“I don’t know. Some was about Sherman Pope. Studies on its structure.”

“Its structure is established, I thought,” Alice said.

“Right. So why give it to me?”

“Maybe someone’s trying to get us to connect the dots.”

“Well, are your dots connecting at all?” Ian spat.

Alice paused, feeling stung, knowing Ian’s anger wasn’t really for her. And even if it was, she was used to being yelled at, and could take it.

“Okay,” Alice said carefully. “I’ve got the public platform. You have the access. Forget trying to figure out why Deep Throat won’t get to the point for a minute, and forget about why he didn’t come to me. That itself feels like an incomplete puzzle, if it’s a puzzle. I feel like I’m being led to BioFuse. You can’t tell me about BioFuse, but you could find out. You could ask.”

“Ask whom? And what the hell am I supposed to do with whatever long-winded bullshit I hear that I won’t be able to make sense of even if I get it without raising a ton of suspicion … when, I’ll remind you, I’ve already been warned? Burgess sounded like he was making a threat. He had two goddamned goons drag me into his office for a lecture on evolution and mission and purpose. Now my wife tells me we’re getting strange calls, and there are people watching my house. My family. I’m not here because I’m a fan of your work or want to expose the truth, as you seem so eager to do. I’m here because I didn’t start any of this, and this feels like the most likely way to make it stop.”

Alice thought. Ian was being driven by fear. Alice was responsible for a few of those hang-up calls to Mrs. Keys, but the rest sounded like threats, sure and true. Fear for himself and his family would motivate him, but altruism wouldn’t. If she wanted Ian’s help, the right levers would need to be applied.

“We need someone who can make sense of whatever you find,” Alice said. “The missing piece of this puzzle, between the mouthpiece and the guy with access.”

“What are you talking about?” Ian asked.

Alice told him.