THE MOMENT WAS SURREAL. IT was dark through the large windows with their fine but anonymous view of the city below. Ian was watching a comedy flick with a name he hadn’t caught and a plot he hadn’t been remotely paying attention to. To one side, on a plush couch, was the actress Holly Gaynor — who, it turned out, must only put on her famous necrotic accent because she had none of it in person. To the other side was Bobby Baltimore, famous deadhead hunter.

He’d heard August Maughan was connected, with a roster of A-list longevity clients. But he hadn’t expected a Who’s Who to be here tonight, nearing ten o’clock, while Ian feared for his family — and, honestly, feared his wife a bit, too.

He checked his phone. Still no returned text from Bridget or missed call. No new voicemails. Or emails.

He could try again. Maybe he even should try again; incessant, never-give-up attempts to contact someone stopped being stalking and became proper when trying to heal an argument with your wife. But Ian didn’t, partly because he’d need to do it on the sly. He might even need to leave the room, in case Bridget miraculously answered.

But mainly he didn’t try again because he knew she wouldn’t take his call. She wouldn’t respond to a text. She’d keep ignoring him, as she’d been doing since he’d left home hours ago to meet August.

Unless Bridget was dead, of course. Bridget and Ana both.

Ian felt restless. He couldn’t get comfortable. There was no proper answer. August would only talk to Ian in person, and their talk had been revealing … to the scientist, anyway. But that had been a while ago now, all four of them pow-wowing to reach conclusions that only August, with his insider knowledge of Archibald Burgess, already knew. He’d gone into his ad-hoc lab. To his computer, with all of the information from the thumb drive, public and general consumption as it seemed to be.

Ian could probably have left after that. He wanted to, but he also felt sure he shouldn’t. This was bigger than his family. This might be the whole world.

He stood. Bobby’s eyes followed.

“They’ll be fine,” Bobby said.

“You don’t know that. Hemisphere doesn’t want me talking, and sicced three ferals on my wife today to prove it. And now that I’m here, they — ”

“Are still being watched by my buddies.”

Ian sighed.

“Do you want me to text them?”

“No. It’s fine.”

“I’ll text them.” Bobby’s phone appeared, and he dictated a message. The response was immediate. Bobby held the screen toward Ian, who of course couldn’t read it from where he was sitting.

“She went to bed ten minutes ago. Nobody’s come knocking.”

Ian closed his eyes and breathed deeply. He didn’t love the idea of Bobby’s hunter friends staking out his house and watching the windows. Seeing Bridget’s light go off as she went to bed alone, far earlier than usual. She was probably lying under the covers, watching TV, feeling nervous and betrayed, with no husband to hold her in the aftermath of her harrowing day.

Ian was about to make an announcement — perhaps that he was leaving and would return in the morning — when August emerged from the kitchen, where he’d set up his lab near the closest water supply.

“I’ve got a Play-Doh Fun Factory in there and need proper equipment to be sure,” he said, removing his little glasses and rubbing his eyes, “but what I’m seeing fits what you told me, Ian.”

Ian looked at Bobby and Holly. Had he missed something while he’d been busy missing every word of the movie?

“I didn’t tell you anything.”

“The files you gave me did. Plus what Alice led me to, the stuff she was given by your tipster.”

“There was nothing in them,” Ian said. “Same for what he gave Alice.”

“I understand why you’d think that,” August said. “But all those public studies and reports on the drive had information hidden in the metadata.”

“I didn’t know that,” Ian said, wondering why anyone would do something so obtuse. “How would you even know to look?”

“It’s something we used to do when I was at Hemisphere. Archibald is paranoid. It’s not enough to obscure information. He was always hiding it in plain sight. Like this.”

“You’re saying those files contained Hemisphere secrets from years ago that they forgot to — ”

“No,” August said, cutting him off. “Archibald is both paranoid and wicked smart. He wouldn’t be that sloppy. What was on those files was put there by your source.”

“What the hell would make him think I’d even find it?”

“I don’t think you were supposed to. He hid what we needed in the metadata then sent it through you because you have access inside the Hemisphere firewall. But what was in there was, I think, always meant for me.”

Ian blinked around at the others, but this part of the discussion meant nothing to Holly and Bobby.

“If this guy wanted to talk to you, why didn’t he just contact you and leave me out of it?” The question made Ian resentful. He hadn’t asked for any of this and didn’t deserve any involvement in this mission of espionage.

“If I had to guess, it’s because your access is needed. You and Alice were both nudged toward me.”

“But nothing direct. Of course.”

“I suspect this is the work of an insider at Hemisphere, like you. Maybe he saw something but didn’t know what it was, and can’t investigate because he fears for his safety.”

Ian huffed. Fuck his safety. What about Ian’s safety?

Bobby was watching August. There was much they’d discussed earlier, before August had disappeared into the kitchen, about Yosemite. About evolution. About things Bobby may have seen — things, as it turned out, that had been bothering Bobby for a while about the aged deadhead population: a population that refused to die, and became harder to kill the older it got.

“What did you find, August?” Bobby asked. “You found something, didn’t you?”

August nodded.

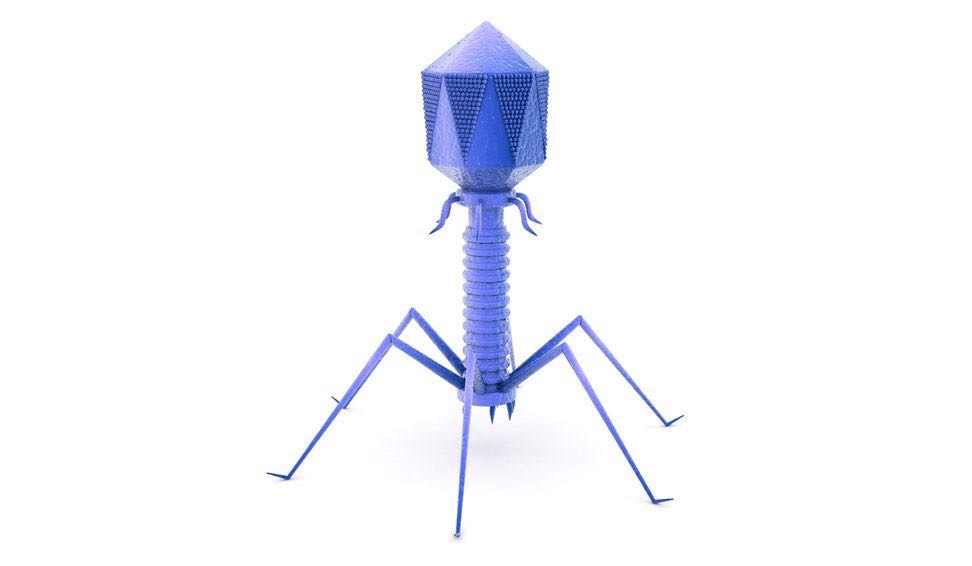

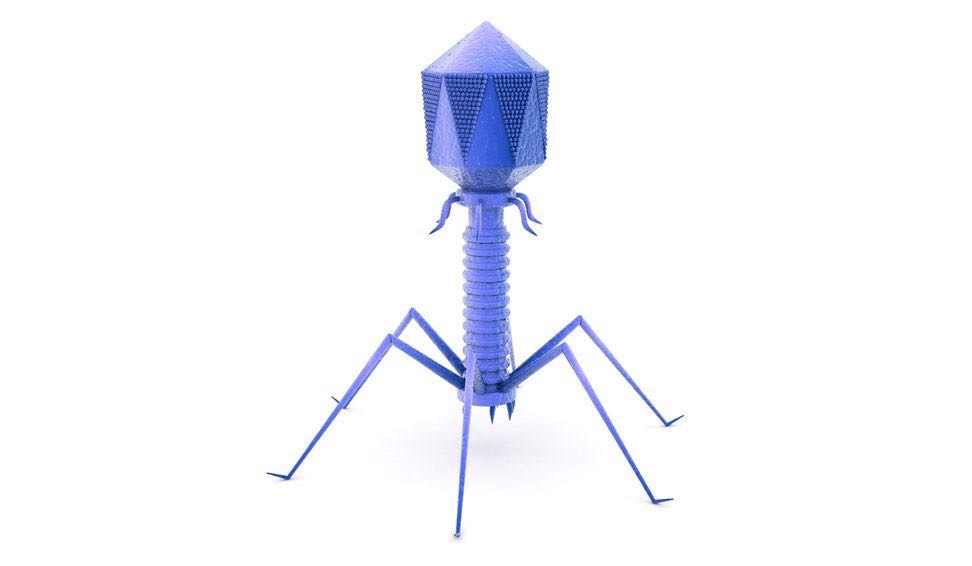

“Sherman Pope appears to be a modified version of a Hemisphere gene therapy virus called BioFuse,” he said.

Ian sat up.

“Hemisphere had the cure,” August went on, “because Hemisphere caused the plague.”