INGREDIENTS

EXCEPT FOR WINES AND SPIRITS, and possibly foie gras and truffles, all the ingredients called for in this book are available in the average American grocery store. The following list is an explanation of the use of some items:

BACON, lard de poitrine fumé The kind of bacon used in French recipes is fresh, unsalted, and unsmoked, lard de poitrine frais. As this is difficult to find in America, we have specified smoked bacon; its taste is usually fresher than that of salt pork. It is always blanched in simmering water to remove its smoky taste. If this were not done, the whole dish would taste of bacon.

Blanched Bacon

Place the bacon strips in a pan of cold water, about 1 quart for each 4 ounces. Bring to the simmer and simmer 10 minutes. Drain the bacon and rinse it thoroughly in fresh cold water, then dry it on paper towels.

BUTTER, beurre French butter is made from matured cream rather than from sweet cream, is unsalted, and has a special almost nutty flavor. Except for cake frostings and certain desserts for which we have specified unsalted butter, American salted butter and French butter are interchangeable in cooking. (Note: It has recently become a habit in America to call unsalted butter, “sweet butter”; there is an attractive ring to it. But technically any butter, salted or not, which is made from sweet, unmatured cream is sweet butter.)

Clarified Butter, beurre clarifié

When ordinary butter is heated until it liquefies, a milky residue sinks to the bottom of the saucepan. The clear, yellow liquid above it is clarified butter. It burns less easily than ordinary butter, as it is the milky particles in ordinary butter which blacken first when butter is heated. Clarified butter is used for sautéing the rounds of white bread used for canapés, or such delicate items as boned and skinned chicken breasts. It is also the base for brown butter sauce, and is used rather than fat in the brown roux for particularly fine brown sauces. To clarify butter, cut it into pieces and place it in a saucepan over moderate heat. When the butter has melted, skim off the foam, and strain the clear yellow liquid into a bowl, leaving the milky residue in the bottom of the pan. The residue may be stirred into soups and sauces to serve as an enrichment.

Butter Temperatures, Butter Foam

Whenever you are heating butter for an omelette or butter and oil for a sauté your recipe will direct you to wait until the butter foam looks a certain way. This is because the condition of the foam is a sure indication of how hot the butter is. As it begins to melt, the butter will foam hardly at all, and is not hot enough to brown anything. But as the heat increases, the liquids in the butter evaporate and cause the butter to foam up. During this full-foaming period the butter is still not very hot, only around 212 degrees. When the liquids have almost evaporated, you can see the foam subsiding. And when you see practically no foam, you will also observe the butter begin to turn light brown, then dark brown, and finally a burnt black. Butter fortified with oil will heat to a higher temperature before browning and burning than will plain butter, but the observable signs are the same. Thus the point at which you add your eggs to the omelette pan or your meat to the skillet is when the butter is very hot but not browning, and that is easy to see when you look at the butter. If it is still foaming up, wait a few seconds; when you see the foam begin to subside, the butter is hot enough for you to begin.

CHEESE, fromage The two cheeses most commonly used in French cooking are Swiss and Parmesan. Imported Swiss cheese is of two types, either of which may be used: the true Gruyère with small holes, and the Emmenthal which is fatter, less salty, and has large holes. Wisconsin “Swiss” may be substituted for imported Swiss. Petit suisse, a cream cheese that is sometimes called for in French recipes, is analogous to Philadelphia cream cheese.

CREAM, crème fraîche, crème double French cream is matured cream, that is, lactic acids and natural ferments have been allowed to work in it until the cream has thickened and taken on a nutty flavor. It is not sour. Commercially made sour cream with a butterfat content of only 18 to 20 per cent is no substitute; furthermore, it cannot be boiled without curdling. French cream has a butterfat content of at least 30 per cent. American whipping cream with its comparable butterfat content may be used in any French recipe calling for crème fraîche. If it is allowed to thicken with a little buttermilk, it will taste quite a bit like French cream, can be boiled without curdling, and will keep for 10 days or more under refrigeration; use it on fruits or desserts, or in cooking.

1 tsp commercial buttermilk

1 cup whipping cream

Stir the buttermilk into the cream and heat to luke-warm—not over 85 degrees. Pour the mixture into a loosely covered jar and let it stand at a temperature of not over 85 degrees nor under 60 degrees until it has thickened. This will take 5 to 8 hours on a hot day, 24 to 36 hours at a low temperature. Stir, cover, and refrigerate.

[NOTE: French unmatured or sweet cream is called fleurette]

FLOUR, farine Regular French household flour is made from soft wheat, while most American flour is made from hard wheat; in addition, French flour is usually unbleached. This makes a difference in cooking quality, especially when you are translating French recipes for yeast doughs and pastries. We have found that a reasonable approximation of French flour, if you need one, is 3 parts American all-purpose unbleached flour to 1 part plain bleached cake flour.

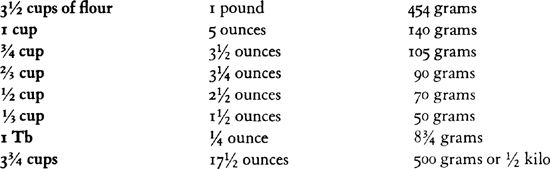

Be accurate when you measure flour or you will run into cake and pastry problems. Although a scale is ideal, and essential when you are cooking in large quantities, cups and spoons are accurate enough for home cooking when you use the scoop-and-level system illustrated here.

For all flour measurements in this volume, scoop the dry-measure cup directly into your flour container and fill the cup to overflowing (A); do not shake the cup or pack down the flour. Sweep off excess so that flour is even with the lip of the cup, using a straight edge of some sort (B). Sift only after measuring.

In first edition copies of this volume all flour had to be sifted, and we advised that our flour be sifted directly into the cup; cake flour weighed less per cup than all-purpose flour, and it was a cumbersome system all around. The scoop-and-level is far easier, and just as reliable. See next page for a chart of weights and measures for flour measured this way.

FLOUR WEIGHTS: Approximate Equivalents (scoop-and-level method)

NOTE: 1 cuillère de farine in a French recipe usually means 1 heaping French tablespoon, or 15 to 20 grams—the equivalent of 2 level American Tb.

GLACÉED FRUITS, CANDIED FRUITS, fruits confits These are fruits such as cherries, orange peel, citron, apricots, and angelica, which have undergone a preserving process in sugar. They are sometimes coated with sugar so they are not sticky; at other times they are sticky, depending on the specific process they have been through. Glacéed fruits are called for in a number of the dessert recipes; most groceries carry selections or mixtures in jars or packages.

HERBS, herbes Classical French cooking uses far fewer herbs than most Americans would suspect. Parsley, thyme, bay, and tarragon are the stand-bys, plus fresh chives and chervil in season. A mixture of fresh parsley, chives, tarragon, and chervil is called fines herbes. Mediterranean France adds to the general list basil, fennel, oregano, sage, and saffron. The French feeling about herbs is that they should be an accent and a complement, but never a domination over the essential flavors of the main ingredients. Fresh herbs are, of course, ideal; and some varieties of herbs freeze well. Excellent also are most of the dried herbs now available. Be sure any dried or frozen herbs you use retain most of their original taste and fragrance.

A Note on Bay Leaves

American bay is stronger and a bit different in taste than European bay. We suggest you buy imported bay leaves; they are bottled by several of the well-known American spice firms.

HERB BOUQUET, bouquet garni This term means a combination of parsley, thyme, and bay leaf for flavoring soups, stews, sauces, and braised meat and vegetables. If the herbs are fresh and in sprigs or leaf, the parsley is folded around them and they are tied together with string. If the herbs are dried, they are wrapped in a piece of washed cheesecloth and tied. A bundle is made so the herbs will not disperse themselves into the liquid or be skimmed off it, and so that they can be removed easily. Celery, garlic, fennel, or other items may be included in the packet, but are always specifically mentioned, such as “a medium herb bouquet with celery stalk.” A small herb bouquet should contain 2 parsley sprigs, ⅓ of a bay leaf, and 1 sprig or ⅛ teaspoon of thyme.

MARROW, moelle The fatty filling of beef leg-bones, marrow is poached and used in sauces, garnitures, and on canapés. It is prepared as follows:

A beef marrowbone about 5 inches long

Stand the bone on one end and split it with a cleaver. Remove the marrow in one piece if possible. Slice or dice it with a knife dipped in hot water.

Boiling bouillon or boiling salted water

Shortly before using, drop the marrow into the hot liquid. Set aside for 3 to 5 minutes until the marrow has softened. Drain, and it is ready to use.

OIL, huile Classical French cooking uses almost exclusively odorless, tasteless vegetable oils for cooking and salads. These are made from peanuts, corn, cottonseed, sesame seed, poppy seed, or other analogous ingredients. Olive oil, which dominates Mediterranean cooking, has too much character for the subtle flavors of a delicate dish. In recipes where it makes no difference which you use, we have just specified “oil.”

SHALLOTS, échalotes Shallots with their delicate flavor and slightest hint of garlic are small members of the onion family. They are used in sauces, stuffings, and general cooking to give a mild onion taste. The minced white part of green onions (spring onions, scallions, ciboules) may take the place of shallots. If you can find neither, substitute very finely minced onion dropped for one minute in boiling water, rinsed, and drained. Or omit them altogether.

TRUFFLES, truffes Truffles are round, pungent, wrinkled, black fungi usually an inch or two in diameter which are dug up in certain regions of France and Italy from about the first of December to the end of January. They are always expensive. If you have ever been in France during this season, you will never forget the exciting smell of fresh truffles. Canned truffles, good as they are, give only a suggestion of their original glory. But their flavor can be much enhanced if a spoonful or two of Madeira is poured into the can half an hour before the truffles are to be employed. Truffles are used in decorations, with scrambled eggs and omelettes, in meat stuffings and pâtés, and in sauces. The juice from the can is added to sauces and stuffings for additional truffle flavor. A partially used can of truffles may be frozen.