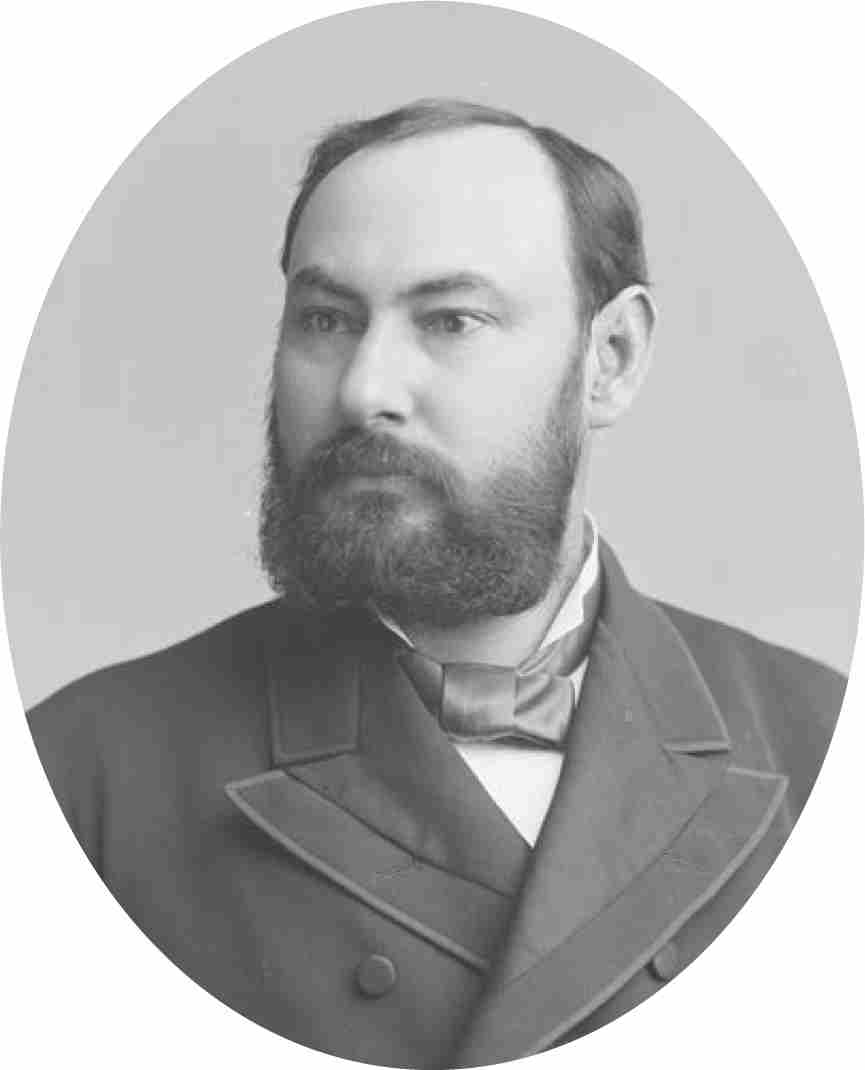

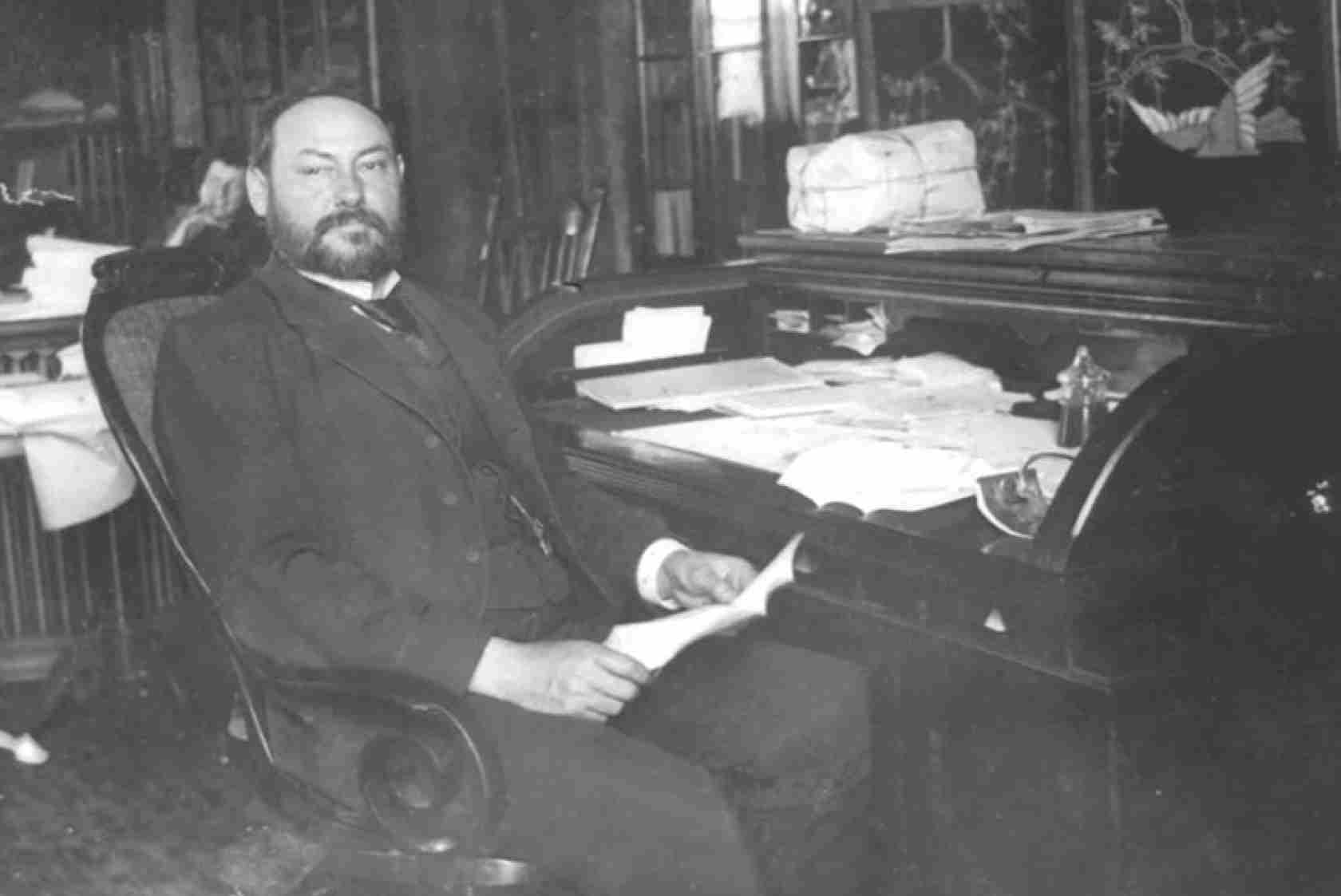

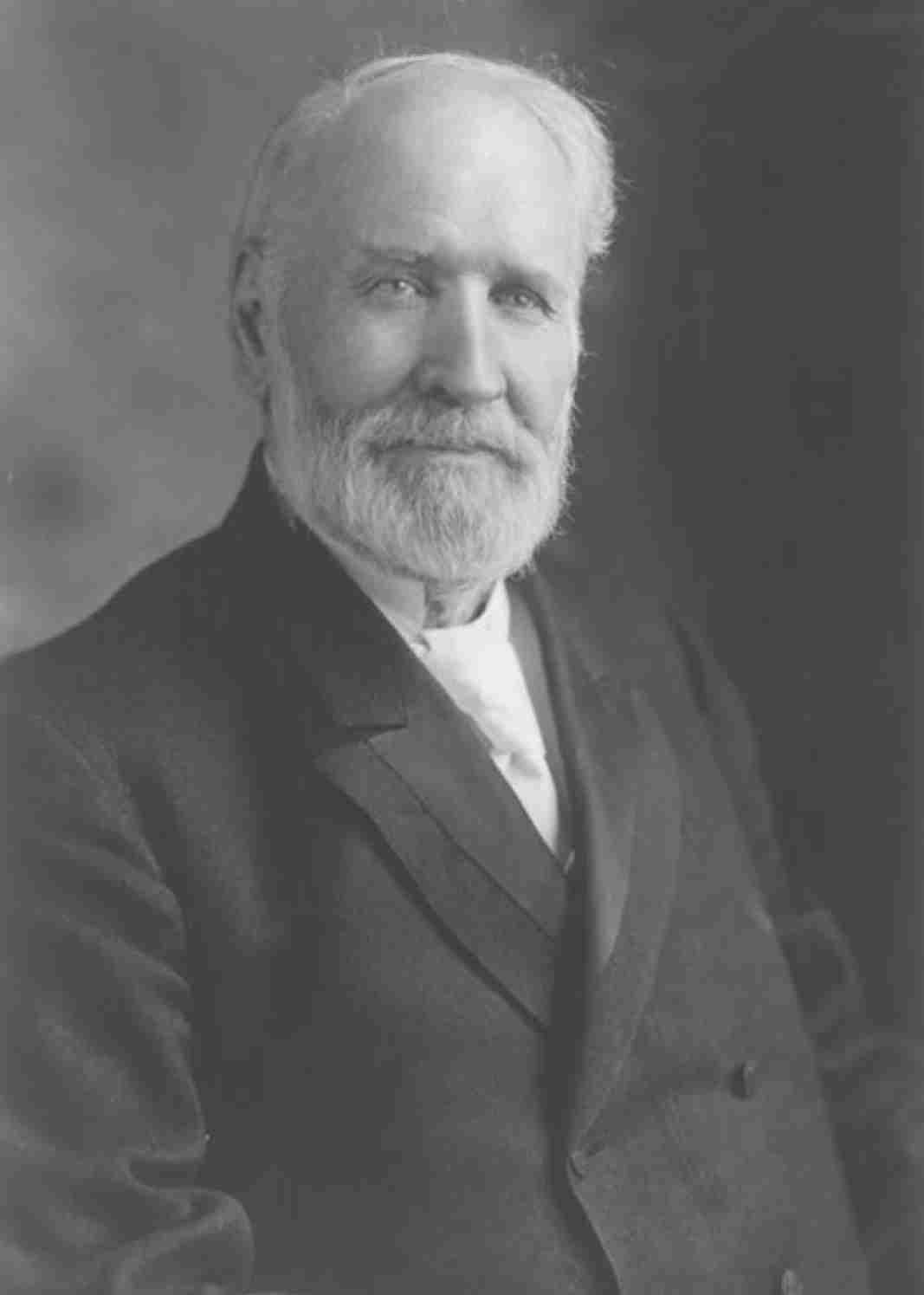

Wiley posed for this portrait around the time he moved to Washington. He was a large man for his day, standing just over six feet and weighing more than two hundred pounds.

“Poisonous adulterations…have, in many cases, not only impaired the health of the consumer, but frequently caused death.”

—Alex. J. Wedderburn

Unlike other instructors at Purdue University, Wiley was young, unmarried, and friendly with his students. He realized that he didn’t fit the professor mold. One day in 1880, he found out that the university’s administration felt the same way.

Wiley was summoned to a meeting of Purdue’s board of trustees. When he arrived, one of them announced, “We have been greatly pleased with the excellence of his instruction.”

Wiley hoped they were about to give him a raise as reward for his effective teaching.

The trustee went on, “We are deeply grieved, however, at his conduct.” He explained that Wiley spent too much time with students outside of class—playing baseball. It was undignified.

“But the most grave offense of all has lately come to our attention,” continued the trustee. “Professor Wiley has bought a bicycle…It is with the greatest pain that I feel it my duty to make these statements in his presence and before this board.”

Well, that was going too far! Wiley’s bicycle, with its large front wheel and small back one, proved to be his undoing.

“Gentlemen, I am extremely sorry that my conduct has met with your disapproval,”

Wiley told the group. “I desire to relieve you of all embarrassment on these points.” He submitted his resignation on the spot.

The board of trustees refused to accept it. After all, Wiley was a highly capable professor. So he stayed, though he bristled under the administration’s strictness.

THE DOC GOES TO DC

Wiley’s sugar research caught the attention of other chemists, including those in Washington, DC. In 1883, he was offered a job in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Division of Chemistry.

Considering the awkward situation at Purdue, he didn’t hesitate. In April, Harvey Washington Wiley took the oath as the Division’s chief chemist.

The chemistry division developed and tested better farming methods, crops, and fertilizers. It also helped protect farmers from food deceptions, such as the substitution of glucose for natural sugars and syrups.

Wiley was part of rural, farming America. But he was part of the world of chemistry and medicine, too. He knew how science could be used to fool a customer.

Wiley posed for this portrait around the time he moved to Washington. He was a large man for his day, standing just over six feet and weighing more than two hundred pounds.

DEATH BY PICKLE

For centuries, unscrupulous people had been making money by tampering with food and beverages. They added cheaper materials or disguised rotten ingredients to appear fresh. These deceptions are called adulteration.

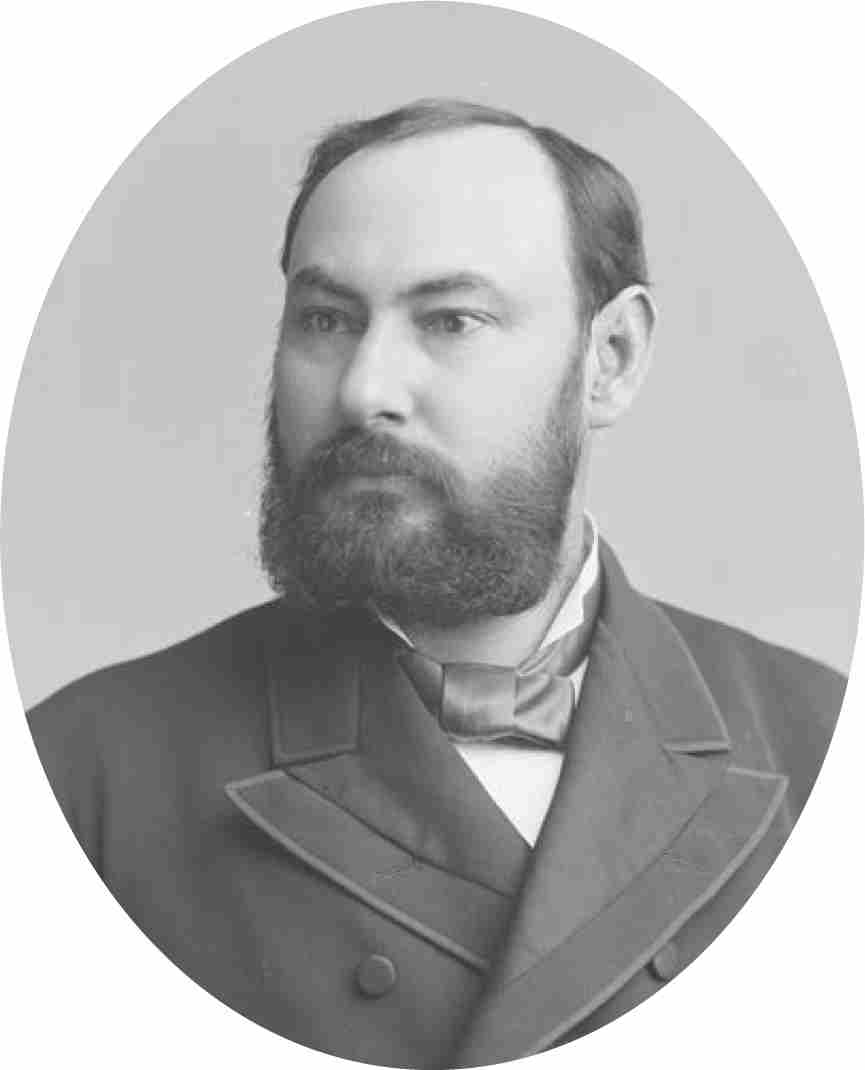

A cartoon appearing in Puck magazine in 1884 shows a chemist testing foods for adulteration. When Wiley took over the Division of Chemistry, concerns were rising about deceptive and dangerous foods.

In 1820, chemist Fredrick Accum (1769–1838) published a book in London detailing the ways dishonest merchants adulterated food, beverages, and drugs.

Accum described how lead was added to cheap white wine to make it clear and seem like better quality. Even then, physicians knew that lead accumulated in the body over time and could cause death.

To look more appetizing, pickles were prepared by soaking the cucumber-vinegar mixture in copper pans. Copper leached into the pickles, turning them greener. Unfortunately, the amount of copper was enough to cause stomach pain, vomiting, or even death in a few pickle-eaters.

Bakers cheated customers by replacing wheat flour with inexpensive ground beans, peas, and chalk as a whitener. Some substituted sawdust for flour in bread.

By the second half of the nineteenth century, the business of adulteration had boomed. So had America.

After the Civil War, the United States changed dramatically. The railroad system expanded at a dizzying pace, connecting cities and towns and allowing people to travel to more places. Steamboats were speedier, making ocean travel easier and bringing more people to American shores. Cities swelled with European immigrants. Though the majority of Americans lived in rural areas, the urban population was rapidly increasing.

Daily life for the average person had changed, too. During Wiley’s youth, most families produced their own food. If they didn’t have a certain item, they bought it from a neighbor. When someone sold poor-quality food, word spread in the small communities. People avoided buying from him again.

But by the 1870s, more and more Americans were living in towns and cities, where many worked at factory jobs. They no longer raised their own food or bought it from a friend. Instead, they shopped in stores stocked with cans of fruits, vegetables, and meats, not knowing where the food came from or who produced it.

CAN IT!

Delivering food to the public became a big business. Food manufacturers supplied stores across the country, shipping products hundreds of miles by railroad. Transporting food long distances took time. That meant the food had to be preserved so that it didn’t spoil before customers received it. Cold temperatures prevent or slow down decay. Refrigeration was still being developed, however, and wasn’t widely available for moving food.

Canning was the solution.

People liked using canned food. It needed less cooking and was quicker to prepare than fresh. A family could get even seasonal foods, like fruits and vegetables, in a can whenever they wanted and at reasonable prices.

There were problems, though. Unlike homegrown food, canned products were touched by many dirty hands between the farm and the processing factory. The foods often weren’t fresh or clean when they were put into containers.

If bacteria are not destroyed during canning or bottling, usually by heat, they have time to multiply before reaching the kitchen table. The food inside the container decomposes, and it can sicken the diner.

Wiley (fourth from left) and several chemists and laboratory assistants take a break outside the Division of Chemistry’s headquarters in 1885. The division’s small staff worked on food and agriculture research in labs in the basement of the Department of Agriculture building.

Decaying food smells and tastes foul, a warning that stops people from swallowing it…but only if they can detect it. Food manufacturers masked those odors and tastes by adding other substances. For example, sugar was used to hide the sour taste of spoiled corn.

During the late nineteenth century, new chemicals were developed that stopped the growth of microbes and slowed down decay. Many canners and food processors rushed to use these preservatives. No one knew what effect the chemicals might have on the human body, particularly in large quantities over a long period.

TURNIPS, PARAFFIN, AND CHARCOAL

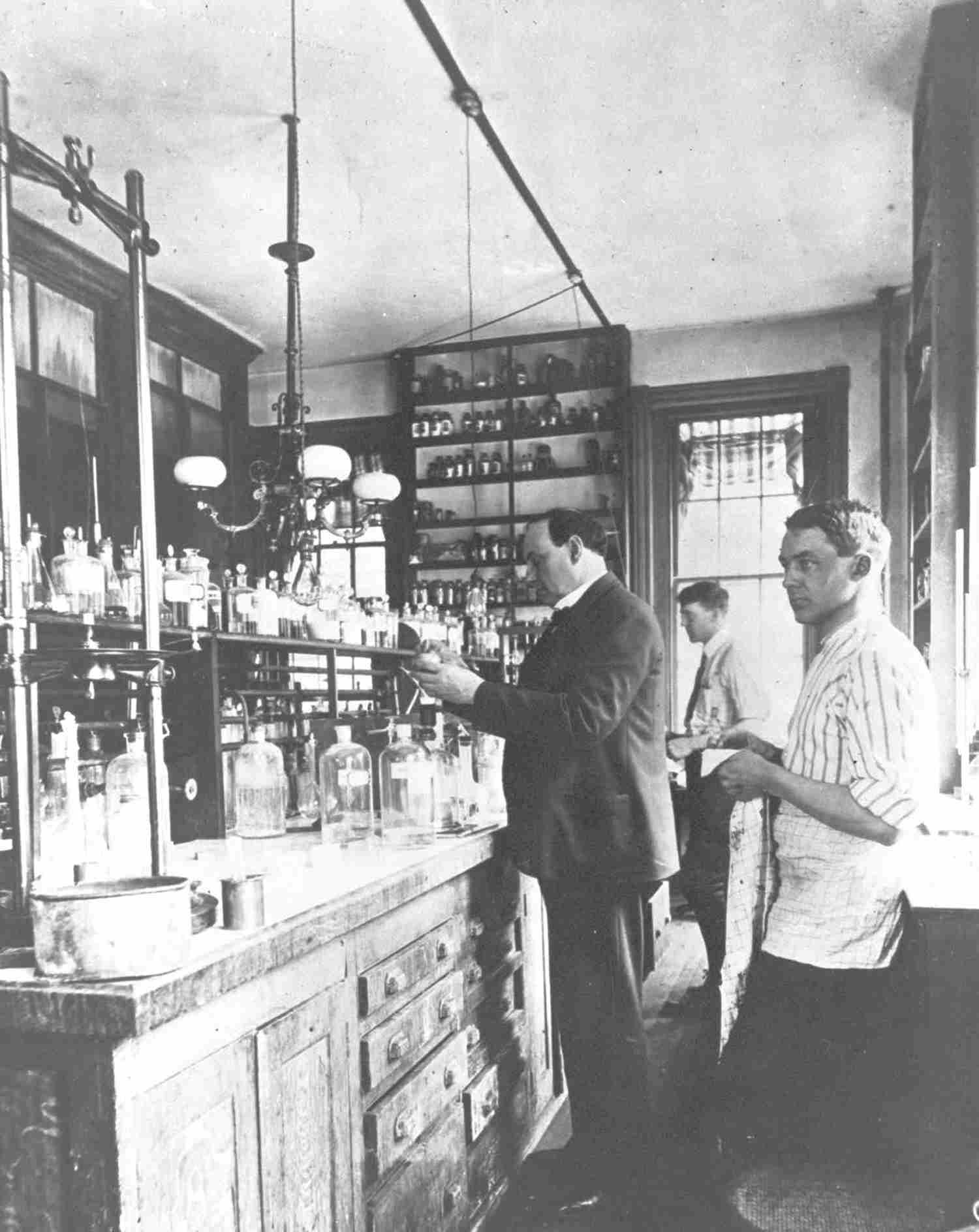

When Wiley arrived at the Department of Agriculture in 1883, the Division of Chemistry had already been studying harmful and deceptive foods. He expanded the research. The chemists became detectives, exposing the true contents of foods and beverages.

Had the canner added a substance to preserve the food or to disguise decay? Had the food manufacturer substituted cheap filler, such as glucose? Under the microscope, cells look distinctive, making it easy to spot ground peas instead of coffee beans or to see mold contamination.

The Division published the results of its scientific tests, showing that nearly every type of food had been adulterated by at least one company. The report listed products that were ripping off or endangering consumers—often both at the same time. Wiley estimated that about fifteen percent of food and beverages on the shelves had been tampered with.

In 1890, Wiley and his staff moved to this brick building across the street from the Department of Agriculture. The tracks embedded in the cobblestone are for streetcars.

Oleomargarine—made from vegetable oil, beef fat, lard, and yellow coloring—was being sold as genuine butter. Dairy farmers, who produced butter from milk, lost business.

Horseradishes sold in stores turned out to be less expensive turnips.

Sausages were made of ground decayed meat. The rotten food was disguised with coloring and spices.

To make rice look whiter and protect it from insects, manufacturers coated the kernels with glucose, talc, and paraffin. Talc is a mineral used in paint and powder. Candles are made from paraffin. The human body can’t digest either one.

In 1893, workers at Armour’s Chicago meatpacking plant use presses to extract oil from beef fat. The oil was turned into oleomargarine, a butter substitute. To deceive the customer, oleomargarine was sometimes colored yellow to look like butter.

Candy contained ground marble to increase its weight. Customers who thought they were buying a pound of pure sweet confection were paying for stone bits, too.

Wiley and his team analyzed pepper samples that were composed mainly of ground corn, cracker crumbs, and charcoal…with scant amounts of real pepper.

Orange juice tested by one chemist was actually sweetened water with citric acid and extract of orange added for flavor. The manufacturer charged customers fifteen times what it cost to produce.

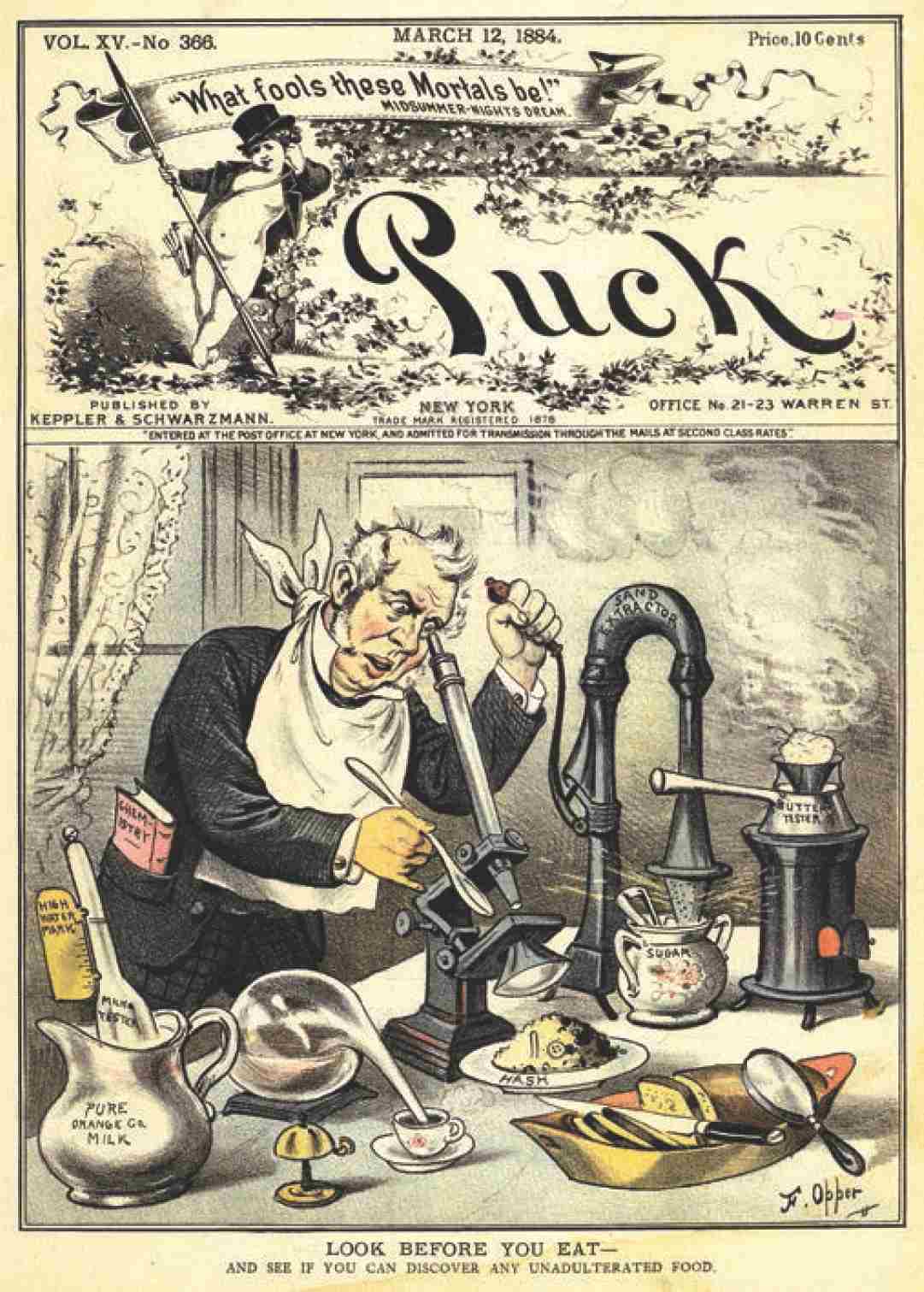

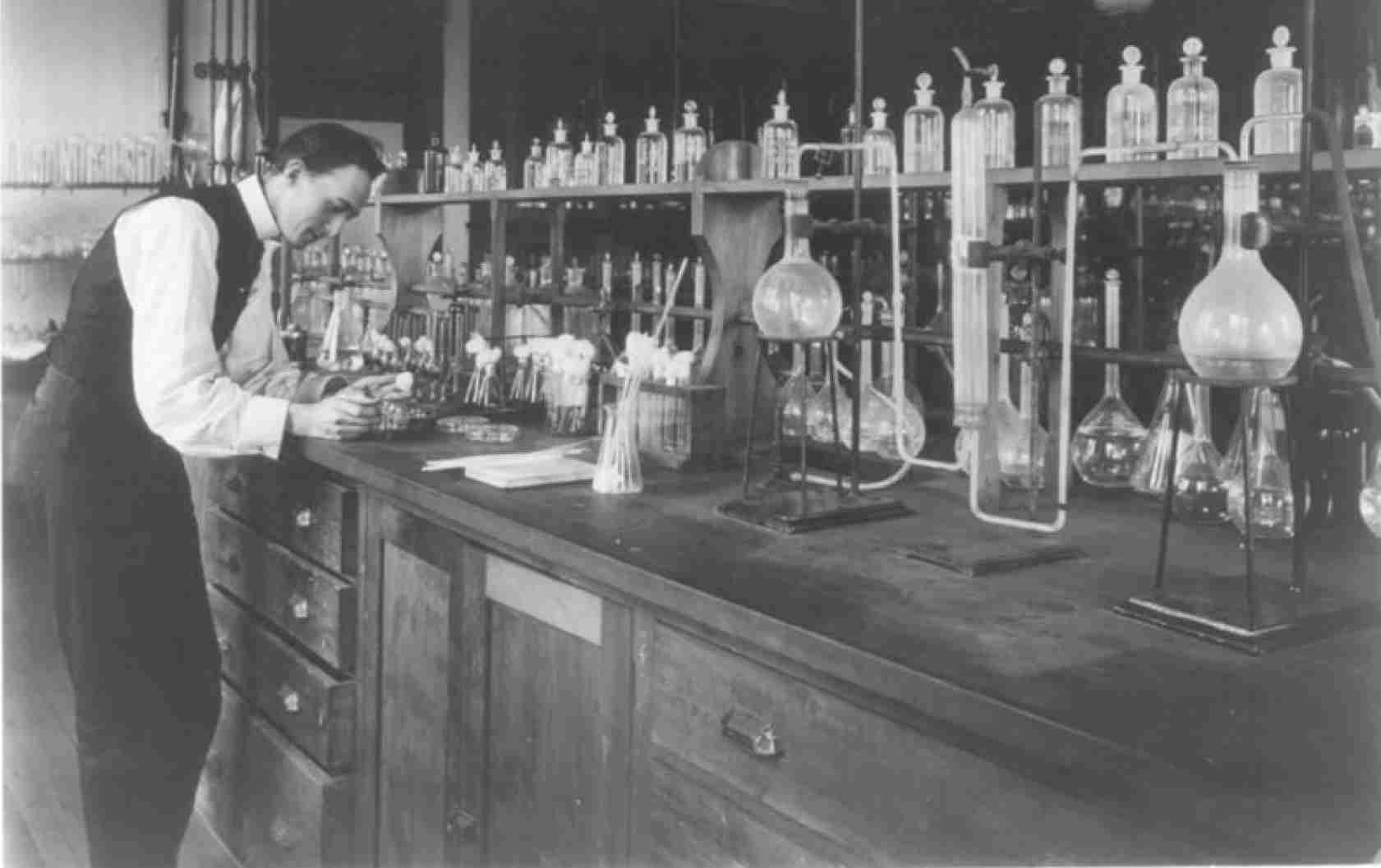

A scientist on Wiley’s staff uses a microscope to analyze the makeup of a food sample. The equipment behind him produced highly magnified photographs.

POISON COLORS

Substituting turnips for horseradishes cheated the buyer without injuring the body. But other adulterations involved substances that might cause physical damage.

Wiley was suspicious of chemical preservatives. Traditional preservatives such as salt, sugar, and spices were known to be harmless. They had obvious tastes so that a diner could tell when food had been preserved. But the new chemical additives had no taste or smell, especially in small amounts. A person was unaware of ingesting them. Wiley wasn’t convinced they were safe.

Borax and boric acid sprinkled on meat and broken eggs stopped bacteria growth and covered up the smell of decay.

Saltpeter (potassium nitrate) was used to preserve meats. It held the red color so that the consumer thought the meat was fresher than it was.

Salicylic acid and sodium benzoate were added to bottled ketchup and canned tomatoes to stop overripe tomatoes from decomposing.

Wiley’s bicycle got him into trouble at Purdue University. In Washington, he bought a car and ran into trouble there, too. He and his steam-run 1900 Mobile were involved in one of the city’s first car accidents. The distracted driver of a horse-drawn delivery wagon rammed into the side of Wiley’s car. The horses and wagon were unscathed, and the driver sped away without stopping to see if Wiley was hurt. The car was badly damaged, but Wiley was only bruised.

Wiley considered the common preservative formaldehyde a risky chemical to eat or drink. Even worse, when formaldehyde was put in milk, it destroyed the bacteria that turned milk sour. Without the warning signs of foul smell and taste, a person couldn’t detect the milk’s age. But because formaldehyde didn’t kill all the harmful bacteria in spoiled milk, the unsuspecting consumer became ill.

By adding preservatives, manufacturers got away with using rotting foods and unsanitary canning methods. Wiley argued that if companies used fresher ingredients and proper sterilization, they wouldn’t need chemicals.

He distrusted food coloring, too. The first chemically produced food dyes were created in 1856. They were cheaper for manufacturers to use than natural plant dyes like paprika red. Because these new dyes were made from processed coal, they were called coal-tar colors. Wiley believed most were “highly poisonous and injurious” and dangerous for children.

Other food colors were made with mercury, a chemical that damages the brain and nervous system. The Division of Chemistry found arsenic in the red coloring used in meat and candy. One yellow dye contained lead and caused convulsions and death in dozens of people who ate cake colored with it.

“The practice of artificial coloring,” said Wiley, “is reprehensible.”

It bothered him that the poor suffered most from adulteration. They could only afford the cheapest food, which was usually the lowest quality, least nutritious, and most hazardous. “The poor man,” he wrote, “while entitled to get a cheaper article, is likewise entitled, as well as the rich man, to protection against deleterious substances.”

Something had to be done. His father had often told him: “Be sure you are right and then go ahead.” Now Wiley was sure. The United States needed a law to keep its food pure and safe.

WOMEN RISE UP

Harvey Wiley wasn’t alone in his concerns. A few European governments wouldn’t allow certain American products to be sold in their countries. That hurt U.S. farmers.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union warned against alcohol and other drugs in bitters, which were sold as health-boosters for children and adults. Brown’s Iron Bitters contained cocaine.

To protect their farmers’ business and their citizens’ health, several state legislatures passed laws during the 1880s and 1890s to stop food fraud. But each state had its own rules. Even food manufacturers who used high-quality ingredients and no chemical preservatives had trouble complying with so many different state regulations. These companies preferred one federal law that applied to all states.

American women were keenly aware of the changes in food, too. While some—mainly unmarried women—had paying jobs, the majority worked within their home, managing the household, caring for family, and preparing meals. They knew that products on store shelves were inferior to foods grown and preserved at home.

Several groups of women spoke out about dangerous food. They were outraged that watered-down and contaminated milk was cheating children of nutrients and making them sick. Babies had died from bad milk. When government leaders failed to do enough about the situation, women mobilized.

The General Federation of Women’s Clubs rallied their members to pressure the U.S. Congress for a national pure-food law. The women wrote letters to elected officials and influenced the male voters in their families.

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union backed a pure-food law that included controls on quack medicines. The WCTU believed people ingested high levels of alcohol, often unwittingly, because these products did not label it as an ingredient. Hostetter’s Bitters, for one, was sold as an herbal tonic to cure whatever ailed you, from stomachache to diarrhea. It contained as much alcohol as whiskey, gin, rum, or any hard liquor served at a saloon or bar.

Eventually, more than one million women joined the pure-food movement. They held meetings, invited speakers, and passed out pamphlets to publicize their cause. Professional women, including schoolteachers, doctors, and nurses, wrote articles for newspapers and presented public lectures. One of them was Dr. Elizabeth Wiley Corbett, Harvey Wiley’s physician sister.

Besides women’s groups, a pure-food law had the support of farmers, fruit growers, grocers, and companies that didn’t adulterate their products. The demands for action grew louder.

CONGRESS CONSIDERS

A few politicians heard. These congressmen and senators introduced dozens of pure-food bills in the U.S. Congress, beginning in the 1880s. Wiley watched as, year after year, Congress let them die. Most were defeated in a committee and never made it to a debate and vote by the entire House of Representatives or Senate.

Harvey Wiley sits at his desk in the Division of Chemistry, June 1893. He signed Division documents as “Chief.”

The Capitol, where the U.S. Congress meets

HOW A BILL BECOMES LAW: THE BASICS

A member of Congress (either a representative or senator) introduces the bill.

A member of Congress (either a representative or senator) introduces the bill.

A committee of the congressional chamber where the bill was introduced (House of Representatives or Senate) considers it. The committee holds hearings, often asking experts to provide information and opinions.

A committee of the congressional chamber where the bill was introduced (House of Representatives or Senate) considers it. The committee holds hearings, often asking experts to provide information and opinions.

The committee debates and votes on the bill.

Based on the committee’s decision, the bill may move to the full House or Senate for debate and vote.

Based on the committee’s decision, the bill may move to the full House or Senate for debate and vote.

If that chamber votes in favor of the bill, it is sent to the other chamber for consideration.

If that chamber votes in favor of the bill, it is sent to the other chamber for consideration.

Both chambers must approve the bill before it can be presented to the president.

Both chambers must approve the bill before it can be presented to the president.

If the president approves and signs the bill, it becomes law.

If the president approves and signs the bill, it becomes law.

For more details of this complicated process, see the U.S. Congress video at Congress.gov/legislative-process.

The White House, home of the president

SECRETARY OF AGRICULTURE JAMES WILSON (1835–1920)

When he was about sixteen, Wilson immigrated to the United States from Scotland with his family, who were farmers. Settling in Iowa, Wilson bought his own farm and became active in Iowa’s Republican politics. He was first elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1872 and served three terms. Wilson was a professor of agriculture at Iowa Agricultural College (now Iowa State University) when President McKinley appointed him Secretary of Agriculture in 1897. Wilson held the post until 1913 under four presidents from William McKinley to Woodrow Wilson. No other Cabinet member has served that long.

Meat-packers, canners, beverage companies, and some food manufacturers convinced members of Congress to oppose every bill. They claimed that their products were perfectly safe and that the quantities of additives were too small to cause health problems. In their view, a pure-food law amounted to unnecessary meddling in their businesses.

Wiley realized that compromises were needed to sway enough legislators to pass a bill. He hoped that a new law would, at least, slap punishments on cheaters. If a food or beverage contained preservatives, colorings, and flavors, he wanted the manufacturer to prove they were safe and to truthfully list the additives on a label. Then, he said, “the consumer will get what he wants, what he asks for, and what he pays for.”

As the pure-food effort stalled in Congress, Wiley tried not to get discouraged. He felt more optimistic after William McKinley became president in 1897 and appointed James Wilson as agriculture secretary.

The new secretary encouraged research by Wiley and his chemists. Under Secretary Wilson, the Division of Chemistry’s responsibilities expanded and more laboratories were set up. In 1901, it officially became the Bureau of Chemistry, and Wiley was its chief.

With the Department of Agriculture in support, Wiley used his position to push harder for the pure-food bill. He cultivated friendships on Capitol Hill. He gathered scientific evidence from his laboratory that congressmen and senators could use in persuading colleagues to vote for the bill. The lawmakers frequently called Wiley to testify before congressional committees as a science expert.

Wiley wasn’t content to fight his battles in Washington. He traveled around the country giving public lectures to church groups, scientists, colleges, and farmers.

Despite his college debate experience and years as a teacher, Wiley had had a “terror of speaking in public” until he was thirty. But the more he faced audiences, the easier it became. As time went on, he learned to give a speech without the aid of a written version. “I never write out an after dinner speech,” he told a Scranton, Pennsylvania, newspaper editor before one of his talks, “since I depend largely upon the local happenings of the dinner for what I have to say.”

When Wiley gave a talk about pure food to a women’s group, he often wore his top hat and tails. He dressed up to show them that their organizations were important. During such a speech in New Jersey, Wiley recruited one of his most effective and energetic allies.

Wiley and his staff on the steps of the Division of Chemistry building, around 1900. He often wore tails and a top hat to work when he was scheduled to give a luncheon speech to a women’s group. Wiley was known as an entertaining and persuasive speaker.

THE “RUDE AWAKENING”

Alice Lakey first became interested in the pure-food movement in the late 1890s while caring for her father in Cranford, New Jersey. By 1903, she was in her midforties and a leader in its local organization. When Wiley spoke in Cranford in November of that year, Lakey introduced herself. Fired up by his speech, she joined the national fight.

ALICE LAKEY (1857–1935) abandoned her dream of becoming a concert singer when she experienced poor health. She later taught voice lessons. As a leader in the pure-food movement, Lakey rallied other women. Although women could not vote in most states, they vigorously lobbied Congress to pass a safe food law.

Lakey was connected to several women’s groups, including the New Jersey State Federation of Women’s Clubs and its national organization. A member of the National Consumers’ League, Lakey formed a committee to study food adulteration. She brought other women’s associations to the movement, including the National Congress of Mothers.

To raise awareness, Lakey wrote articles for the newsletters of these organizations. She gave talks all over the country, sharing information that Wiley sent her.

In one speech, Lakey told a gathering in New York City about coffee containing clay and “the sweepings of the bake shops.” She informed the shocked women, “Much of our grape jelly is made of apple waste, glucose, and coal tar dye.” She talked about a Boston baker who “used 1,000 pounds of bad eggs a day. These were deodorized with formaldehyde.”

Lakey was confident that the pure-food movement would succeed. “A rude awakening,” she wrote, “convinced [the average woman] that what she was feeding her family did not meet the standards of human decency.”

A research chemist in a Bureau of Chemistry laboratory

Yet Wiley’s speeches and the lobbying by women’s groups and other organizations weren’t enough. The opponents’ voices were louder and more persuasive. Congress continued to vote down every pure-food bill that was introduced.

Wiley knew that without more support from the public, Congress would never pass a pure-food law. He believed that most Americans were still in the dark about the dangers in their food. There had to be some way to grab their attention.

Although Chief Wiley spent much of his time as an administrator, he enjoyed getting into the laboratory.