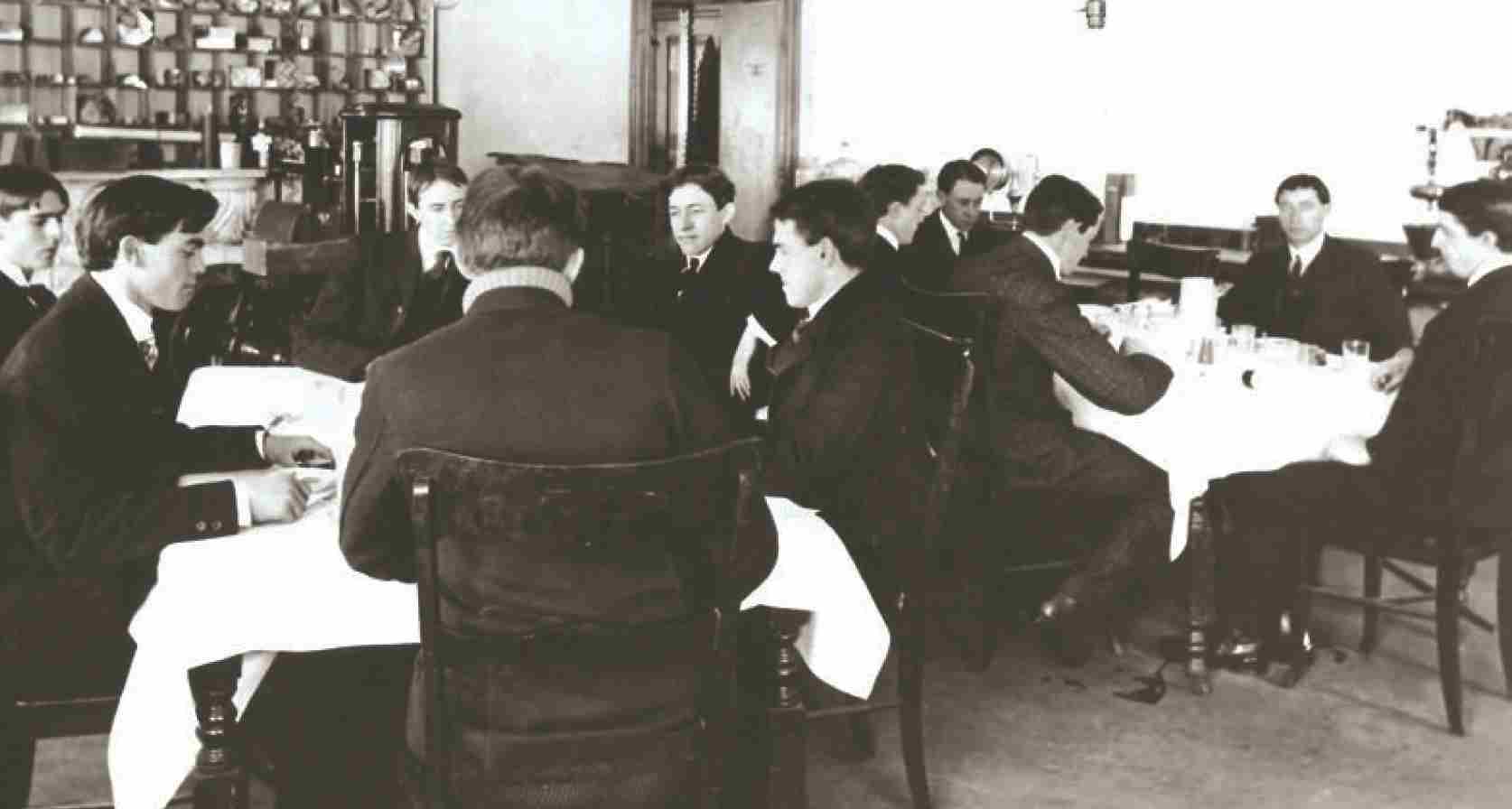

Wiley and ten of the first dozen guinea pigs

“We told them that they might receive some injury from it.”

—Harvey Wiley

Wiley had been critical of food preservatives for nearly twenty years. He and other scientists suspected that the chemicals might disrupt normal digestion. Because a preservative slowed the breakdown of food outside the body, they reasoned, it could slow the breakdown inside the body, too. That would interfere with the release of food nutrients, compromising health.

Other food researchers said the opposite: the preservatives sped up digestion.

Wiley decided it was time to investigate exactly how the human body reacted to these chemicals.

SETTING UP THE EXPERIMENT

As a chemist, Wiley was accustomed to testing his hypotheses in the laboratory. “I arrive at my conclusions by experimentation, when experimentation can be used at all,” he said. In 1902, he persuaded Congress to fund a study by the Bureau of Chemistry.

The questions he hoped to answer were: Do preservatives, colorings, and other food additives affect health? And if so, what quantities—if any—are safe?

He started with borax and its close relative boric acid. Food manufacturers added both preservatives to meats, butter, and milk to stop the growth of microbes. Dishonest companies also used them to disguise old foods as fresh ones.

Germany had banned American food containing borax based on an earlier experiment with two men. After eating various amounts of the chemical, the two suffered stomach irritation and diarrhea. Wiley believed that if his study found no danger, it would counteract the German research. But if borax proved harmful, it might convince manufacturers to stop using it and perhaps even rally the public and Congress behind a pure-food bill.

NONE BUT THE BRAVE

Wiley didn’t think he could get worthwhile results from test animals because their digestive systems differed from humans. He needed human guinea pigs, preferably strong, healthy males. Wiley figured that a young man’s body could better withstand the chemicals’ possible ill effects. If those men were sickened by a preservative, then it “would naturally follow that children and older persons, more susceptible than they, would be greater sufferers.”

He put out the call for young male volunteers within the Department of Agriculture. As part of the experiment, Wiley announced, they would be fed nourishing meals containing an addition of “ordinary preservatives and coloring matters used in foods.” In return, all meals would be free, prepared and served in the basement of the Bureau of Chemistry building. For a young man living on a limited budget, that sounded like a good deal.

The volunteers were allowed to live in their homes and keep their regular jobs. Those who didn’t work for the Department of Agriculture were paid five dollars a month so that they could be legally considered employees. A few applicants were medical students or had jobs in other government departments.

Of the men who put in their names, Wiley chose only those who were free of disease and illness during the previous year. He sought subjects who didn’t use tobacco or alcohol regularly, but he couldn’t find enough of them. He had to settle for including those who smoked, though they were required to record their tobacco use. He rejected anyone who consumed alcoholic drinks. Alcohol contains calories, which would complicate the experiment.

Twelve men made the cut. Most were in their twenties. Wiley later explained to a congressional committee, “We told them, of course, that there was no danger by poisons, but that there might be some disturbance to their systems.”

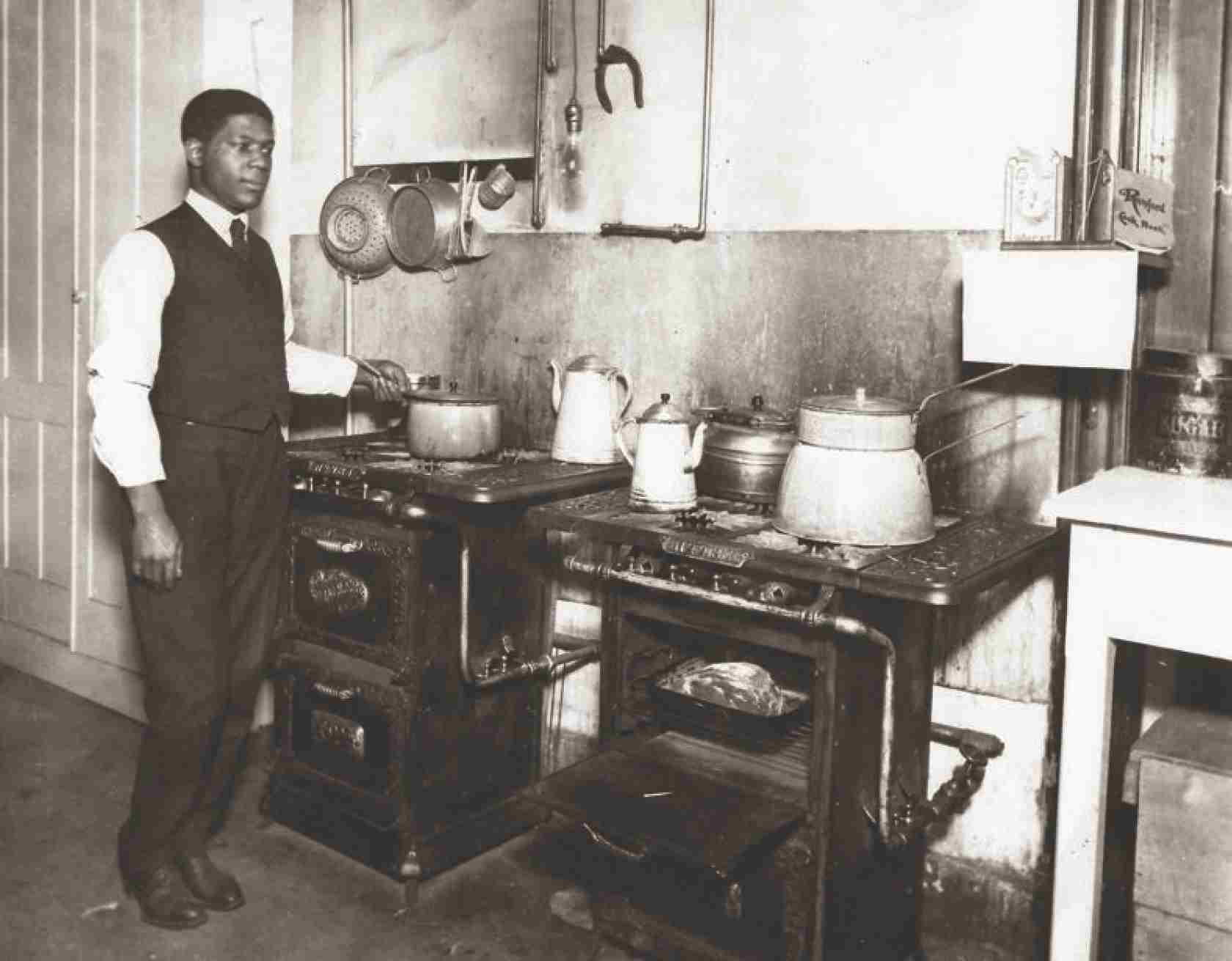

Wiley and ten of the first dozen guinea pigs

William Carter started out as waiter for the Hygienic Tables in 1902. He later took over as cook for most of the investigations.

The men had to commit to the experiment for at least six months and agree not to hold the government responsible if they became sick from the diet.

DIG IN

Once Wiley had his initial group of twelve subjects, he and his staff gathered preliminary information. One effect of the chemical additives might be weight loss. So they first determined the amount of food each man needed to maintain his normal weight.

For ten days at the beginning of the study, all the men were fed a healthy diet without preservatives. Each was weighed daily, and his food portions were adjusted to keep his weight steady.

The borax experiment began in December 1902. A cook prepared three meals a day. The menu rotated on a seven-day cycle and included a variety of meats, fruits, vegetables, and bread. A waiter served the volunteers at oak tables covered with white cloth. Wiley called them the Hygienic Tables.

All twelve men received the same foods. They had to eat everything they were served, “whether they wanted it or not.” If a volunteer didn’t eat his assigned portion, Wiley wouldn’t be able to tell whether his weight change was due to the added chemical or to his food intake.

Wiley added a small amount of the chemical to butter, and then to milk and coffee. Although borax and boric acid are tasteless, the men soon realized where the preservative was hidden. They balked at eating that food, wrecking the experiment.

To guarantee that the volunteers ingested the measured amount of test chemical, Wiley put it in capsules, which the men swallowed with their meals. He thought the chemicals would mix with food in the stomach so that using capsules wouldn’t affect the study.

At first, the dose of added preservative matched the amount typically found in butter and meat. Gradually, Wiley increased the quantity to find how much each man could tolerate.

COLLECT AND MEASURE

Bureau chemists assigned to the feeding study measured the weight and volume of everything the men ate or drank. They analyzed the food for water, fat, calories, and various chemicals.

For the human guinea pigs, though, the experiment wasn’t quite as easy as simply eating. Each man had to fill out daily forms with his weight, pulse rate, and body temperature before and after meals. He recorded everything he consumed. He could eat only what he received at the Hygienic Table. If he was thirsty and drank water between meals, he had to measure and report the amount.

Chemists analyzed the volunteers’ food and waste. This photo was taken in a Bureau of Chemistry laboratory.

That wasn’t the worst part. In order to find out if the test chemical interfered with digestion and if it passed out of the body, all the men’s waste was measured and analyzed. The volunteers collected their urine in bottles and their feces in cans. Each day, they turned the excretions over to Wiley’s lab staff.

A doctor from the U.S. Public Health Service examined the volunteers regularly, noting whether anyone showed symptoms from downing the preservatives. When someone felt too ill to continue, he was taken off the chemical and fed the same menu without it. Wiley’s goal was to learn how much preservative created discomfort, not to overload or permanently damage the men’s bodies.

Wiley assumed that any physical reaction was likely caused by the added chemical because that was the one thing that changed. If the ill man recovered after being off the test diet, Wiley considered it further proof that the preservative was the culprit.

The volunteers weren’t sure how they would react to their new diet, and they adopted this slogan.

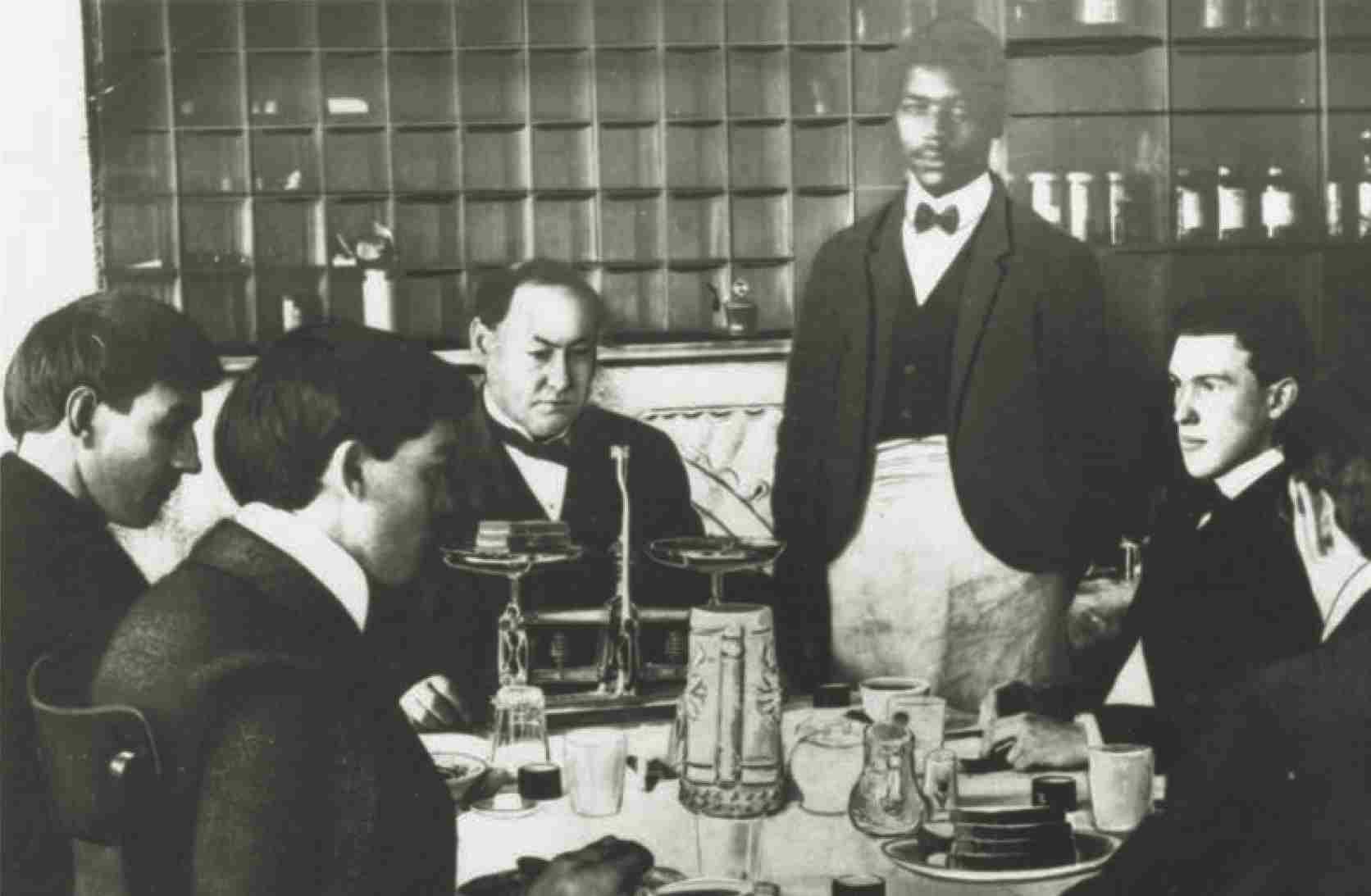

Wiley (third from left) liked to eat with the volunteers. In front of him is a scale for weighing the served bread. The waiter (standing) brought food from the kitchen.

Although he had many responsibilities as head of the Bureau, Wiley kept a close eye on the investigations. Early each morning, he walked two miles from his house to the basement kitchen. Arriving by seven, he often helped weigh the volunteers’ portions. Then he sat down to eat breakfast with them. He ate lunch and dinner at the Hygienic Tables, too—without the borax or boric acid. When Wiley was away from Washington, his assistant W. D. Bigelow supervised the experiment.

THE FAMOUS BOARDING HOUSE

When word of Wiley’s investigation leaked out, a young Washington Post reporter, George Rothwell Brown, jumped on the story. Throughout the beginning months of the experiment, he visited the dining room regularly and wrote articles detailing the study’s progress.

Brown even named some of the volunteers, called boarders in his articles. Though Wiley had kept their identities secret, Brown found out, probably by talking to the volunteers themselves.

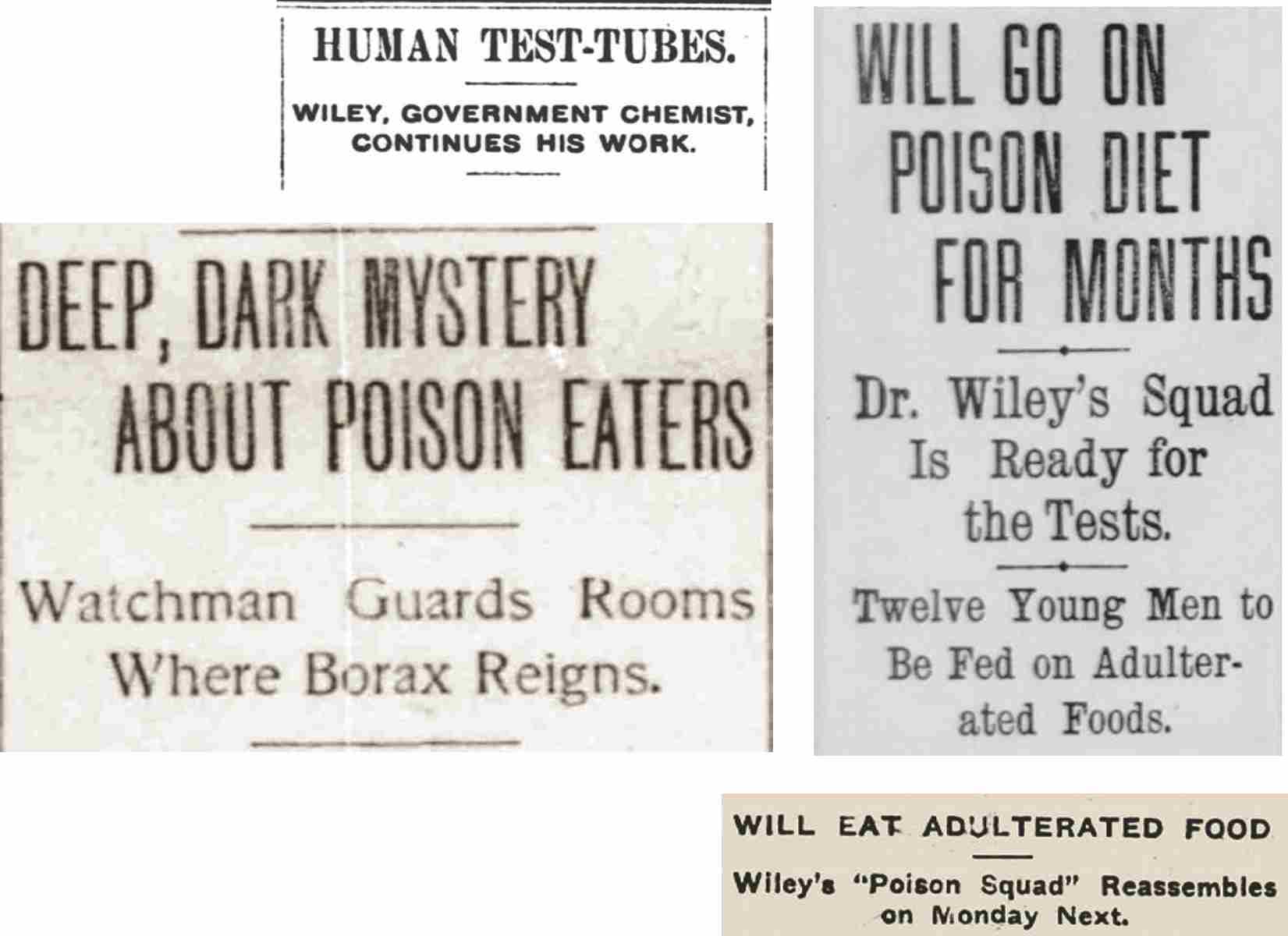

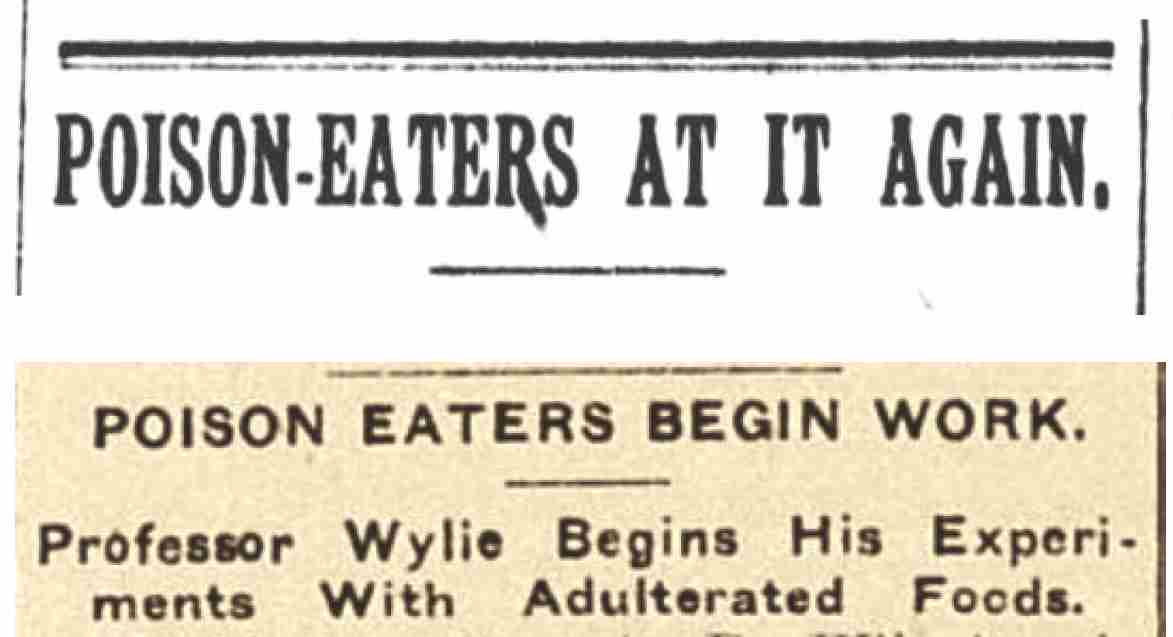

George Rothwell Brown’s articles in the Washington Post brought nationwide attention to the Poison Squad experiments. These headlines are from newspapers that picked up the story: the Washington Standard [Olympia, WA], March 31, 1905 (top left); the Washington [DC] Times, December 29, 1902 (bottom left); the San Francisco Call, October 12, 1903 (top right); and the Bemidji [MN] Daily Pioneer, January 7, 1905 (bottom right).

Headlines like “Second Day and No Fatality” and “Gloomy Christmas Dinner” grabbed newspaper readers’ attention. Many of Brown’s articles were total fiction, meant to be humorous. One mentioned that eating borax gave a pink tinge to the boarders’ faces. Women wrote Wiley letters asking for more information about the new beauty aid.

Wiley was not pleased that Brown invented false details in order to tell an interesting story. He instructed his volunteers to stop talking to the reporter about the experiments.

But Brown continued to write his articles, and other newspapers picked them up. Soon, people across the country were reading about “poison eaters,” “ ‘poison’ capsules,” and the “poison squad.”

Wiley didn’t like the use of “poison.” That made it sound as if he had already decided that the tested chemicals were harmful before conducting the experiment. Besides, the preservatives were not poison, a term that means toxic—causing serious harm or death, even in minute amounts.

He complained to the Post about the misleading articles and received a response from editor Scott Bone in late December 1902. “Our young man has not intended to be fanciful, but has aimed to make his stories readable, and in this he has succeeded.” Bone referred Wiley’s complaint to the city editor who, Bone promised, “no doubt…will respect your wishes.”

Yet Wiley eventually saw the benefit of Brown’s articles. News stories about the Poison Eaters reached millions of readers nationwide. Wiley had wanted the public to take notice of the chemicals in their food. Now they had. Dr. Wiley’s Poison Squad became famous, and he started to use the nickname himself. He called his Hygienic Tables “the most widely advertised boarding house in the world.”

Brown’s articles put a human face on the issue of preservatives and pure food. Many people were interested in the volunteers who bravely agreed to test the chemicals, though others criticized Wiley for exposing the young men to risk.

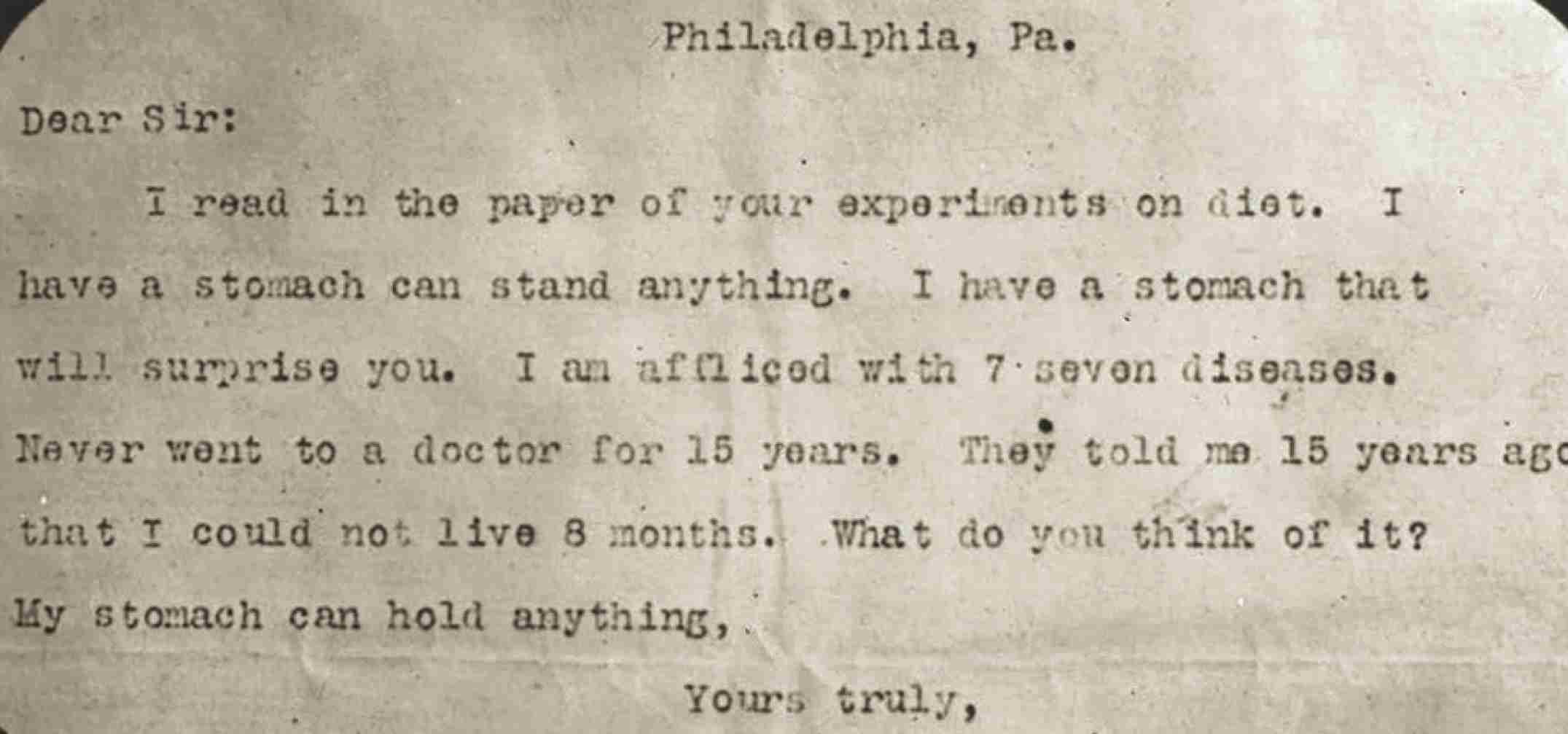

Despite its nickname, the Poison Squad didn’t scare off the volunteer who sent Wiley this letter. The man wasn’t hired.

Newspapers called Wiley “Old Borax,” and some made fun of his Poison Squad. One writer penned a song about it:

If ever you should visit the Smithsonian Institute,

Look out that Professor Wiley doesn’t make you a recruit.

He’s got a lot of fellows there that tell him how they feel,

They take a batch of poison every time they eat a meal.

For breakfast they get cyanide of liver, coffin shaped,

For dinner, undertaker’s pie, all trimmed with crepe;

For supper, arsenic fritters, fried in appetizing shade,

And late at night they get a prussic acid lemonade.

They may get over it, but they’ll never look the same.

That kind of a bill of fare would drive most men insane.

Next week he’ll give them moth balls, a la Newburgh, or else plain.

They may get over it, but they’ll never look the same.

THE VERDICT IS IN

Newspapers across the nation announced the beginning of Wiley’s second series of experiments, on salicylic acid: the New York Sun, October 13, 1903 (top) and the Evening Times-Republican [Marshalltown, IA], September 17, 1903.

The borax/boric acid experiment went on through five separate test periods until June 1903. In each period, the volunteers swallowed chemical capsules for about a month, then went back to eating the menu without preservatives.

After those tests, Wiley and his staff continued the same experiments on different groups of volunteers using other food additives. For five years, until 1907, the Bureau of Chemistry tested sodium benzoate and the related benzoic acid, salicylic acid, sulfurous acid and sulfites, formaldehyde, copper sulfate, and saltpeter.

By the second year, more than two dozen Bureau employees—besides the preservative-eating volunteers—were assigned to work on the studies. That included eight chemists and their lab assistants, as well as five or six people who did the mathematical computing.

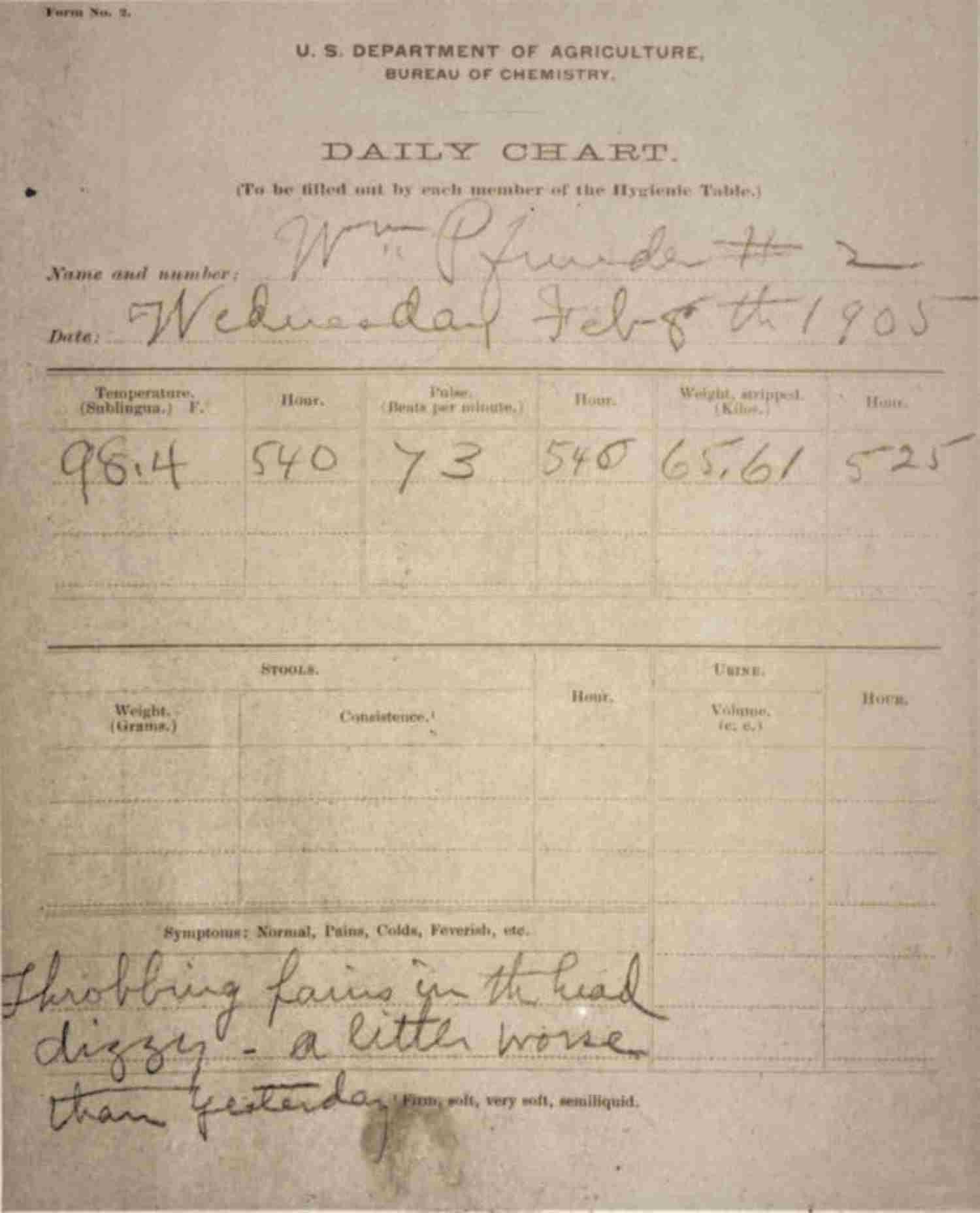

Squad members filled out daily charts about their health. This volunteer’s February 1905 report was from one of the unpublished investigations, either copper sulfate or saltpeter.

The volunteers reacted to high doses of the chemicals with stomach and intestinal pain, loss of appetite, headaches, and nausea. One young man recorded his physical symptoms on his daily chart: “Throbbing pains in the head; dizzy—a little worse than yesterday.” The side effects lingered in some Squad members for several months until they regained normal appetite.

After the Bureau analyzed the experiments’ results, Wiley concluded that the chemicals might not be dangerous in slight amounts. But he thought they could accumulate in the body, causing “disturbance to digestion and health.” While a vigorous young person could tolerate high doses, Wiley feared that the sick and frail might not.

In what amounts could a preservative prevent food spoilage without harming diners? Wiley decided, “There can never be any agreement among experts or others respecting the magnitude of the small quantity.” These chemicals shouldn’t be used “where it can possibly be avoided.” They never should be added, he argued, just because it was easier and cheaper for the food manufacturer. If a preservative did harm, it should be banned.

“I say, as a plain business proposition,” Wiley reported to Congress early in 1906, “that the men who put preservatives in foods had better stop it for their good and for the good of their business.”

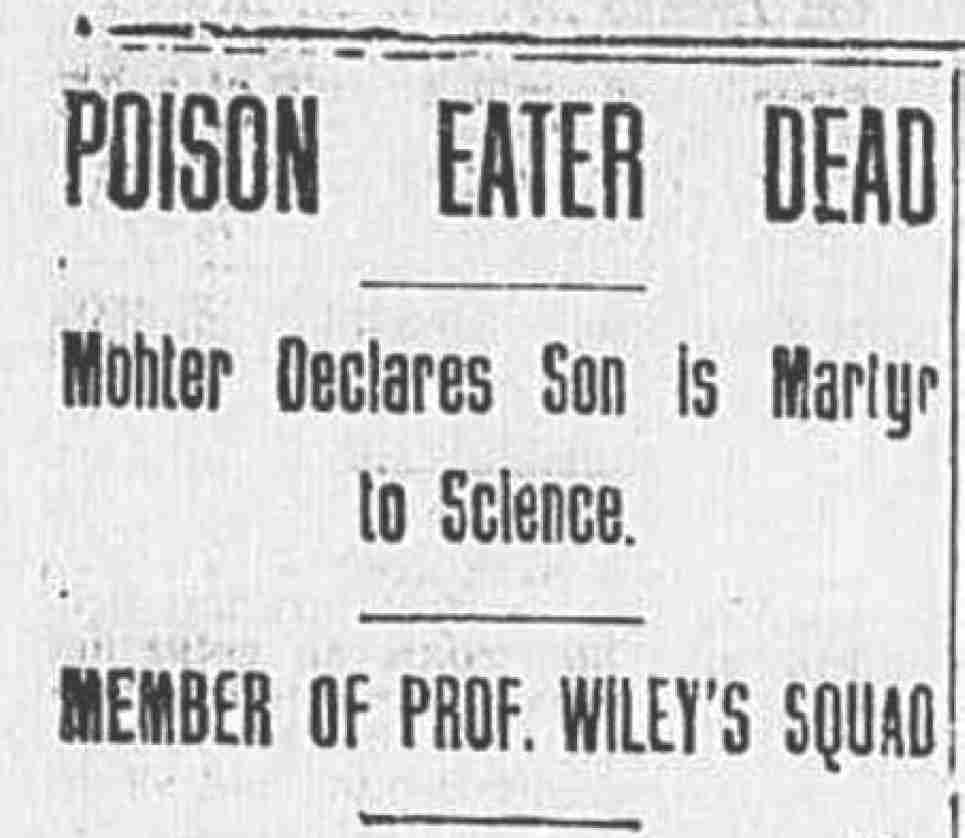

Robert Freeman’s death was widely reported. This headline appeared in the Daily Press [Newport News, VA], November 23, 1906.

A CASUALTY?

In November 1906, twenty-three-year-old Robert Freeman died of tuberculosis in Washington. He had been in the first group of Poison Squad members from 1902 to 1903, and his shattered mother blamed her son’s death on the experiment.

She claimed that Robert had been strong and healthy until joining the borax test. He developed tuberculosis soon after leaving the Squad, she said, likely because his body had been weakened by the “poisonous adulterants” in his food. She told a newspaper “that the Government or Dr. Wiley should pay damages for the death of her son.”

When questioned by the press, Wiley denied that the Poison Squad had any connection to Freeman’s illness. The young man had developed breathing trouble in January 1903, Wiley explained. When he didn’t recover, he was dropped from the experiments that spring. At that time, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death in the United States, with its victims often younger than thirty.

Through January 1907, the Freeman story appeared on the front pages of Washington newspapers and some national ones, too. In one article, a newspaper reported on several congressmen who commented that “it is a bad practice to allow the lives of the citizens of the United States to be imperiled in any degree by any experiments with poisoned food.”

Freeman’s mother never filed a lawsuit, and nothing ever came of the accusation in Congress. His death apparently was a tragic coincidence. As far as history shows, none of the Poison Squad members suffered lasting effects from the experiment. At least one man lived to be ninety-four.

CRITICS SPEAK OUT

Wiley believed his tests showed that food preservatives could cause harm. But his experiments didn’t impress everyone. Critics found many flaws.

One was the lack of a control group. If Wiley had stuck to his original plan, the twelve men would have been eating the same food at the same time in the same place. Six would have received the preservative with their food. The other six—the controls—would not. A volunteer wouldn’t have known which group he was in. The physical complaints of the test group could have been compared to the controls. That would have indicated whether the chemicals caused the reactions.

But Wiley abandoned the initial procedure because it was less convenient than feeding all twelve men the preservative at the same time. That eliminated the control group. Volunteers knew when they were being served the chemical additive. So did the people who served them; the doctors who examined them; the chemists who analyzed their waste; and Wiley, who ate with them. This might have influenced the experiment’s results. Did the Squad members report dizziness or nausea because they knew they had ingested the chemical?

The volunteers gather for a meal in the basement dining room at the Bureau of Chemistry.

When Wiley started using capsules instead of mixing the chemical into food, he might have avoided this bias. He could have given out the capsules all the time to all the volunteers, even when they were getting chemical-free meals. The capsules could have been filled either with the preservative or with a harmless substance. The volunteers wouldn’t have known which.

Another complaint about the experiments was that the analysis of the men’s metabolism and body chemistry showed little change after they received a preservative. Did their nausea or stomach pain depend on the food they ate with the capsule, or the chemical itself?

In one test, Wiley reported that volunteers had headaches, sore throats, achy muscles, and losses of appetite. A critic pointed out that flu was common in Washington during that period and might have been the cause of these ailments. He charged that Wiley hadn’t adequately controlled for outside illnesses.

The Bureaus number crunchers computed experimental data with a Thacher Calculating Instrument. Patented in 1881, the device was used by scientists and engineers. The cylindrical slide rule was about eighteen inches long.

UNCONVINCING

Skeptics also said the Poison Squad members weren’t average consumers. Maybe women or children or older people would have responded to the chemicals differently.

A related objection was that Wiley used too few subjects. He responded that he would have preferred several dozen in each experiment, but he didn’t have enough staff to handle the analysis of that much data. In his words, it was a “great mathematical labor of tabulating, computing, averaging, and studying the data for a period covering seven months.”

Some detractors claimed that Wiley couldn’t be certain his volunteers ate and drank only at the Hygienic Tables. Wiley argued that his chemists could detect an extra snack by analyzing the men’s feces and urine. His critics weren’t convinced.

Wiley expected criticisms from scientists working for the food preservative industry. But he received negative comments from fellow chemists, too.

When he gave a speech at the Chemists’ Club in New York City in early April 1905, a Columbia University professor confronted him. The experiments didn’t provide enough results to make conclusions, the man declared. Plus, they weren’t ethical.

A Chicago chemist agreed: “Dr. Wiley is doing the best he can to frighten the public.”

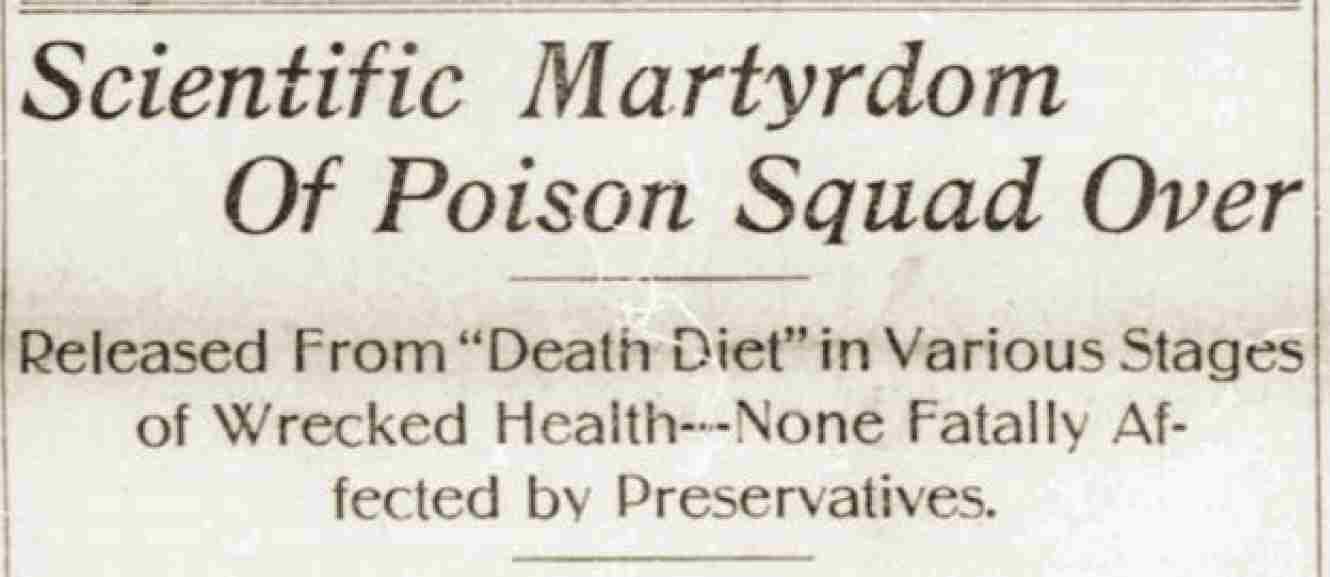

This headline appeared in the Washington [DC] Times, May 21, 1904, at the completion of the sodium benzoate study.

Another audience member warned that a pure-food law should not be based on Wiley’s Poison Squad tests. “You could take any ten men,” he said, “give them something once a day for fifty days, and tell them that they were eating poison and at the end of that time they would all have lost flesh.”

Wiley had never shied away from attacks. “I’ve been roasted before,” he replied. “I’m perfectly willing to be here.” Even though all food adulterations weren’t harmful, he told the audience, it was morally wrong for manufacturers to slip them in. “If any American citizen wants a food product containing any preservative he ought to be allowed to have it, but I say that those who don’t want such a product ought not to be deceived and compelled to take it.”

Ordinary Americans didn’t notice the flaws in Wiley’s experiments…or care. They were disgusted and unnerved by the idea of chemicals in their food. The famous Poison Eaters had given the pure-food movement the boost it needed.

QUACK MEDICINES

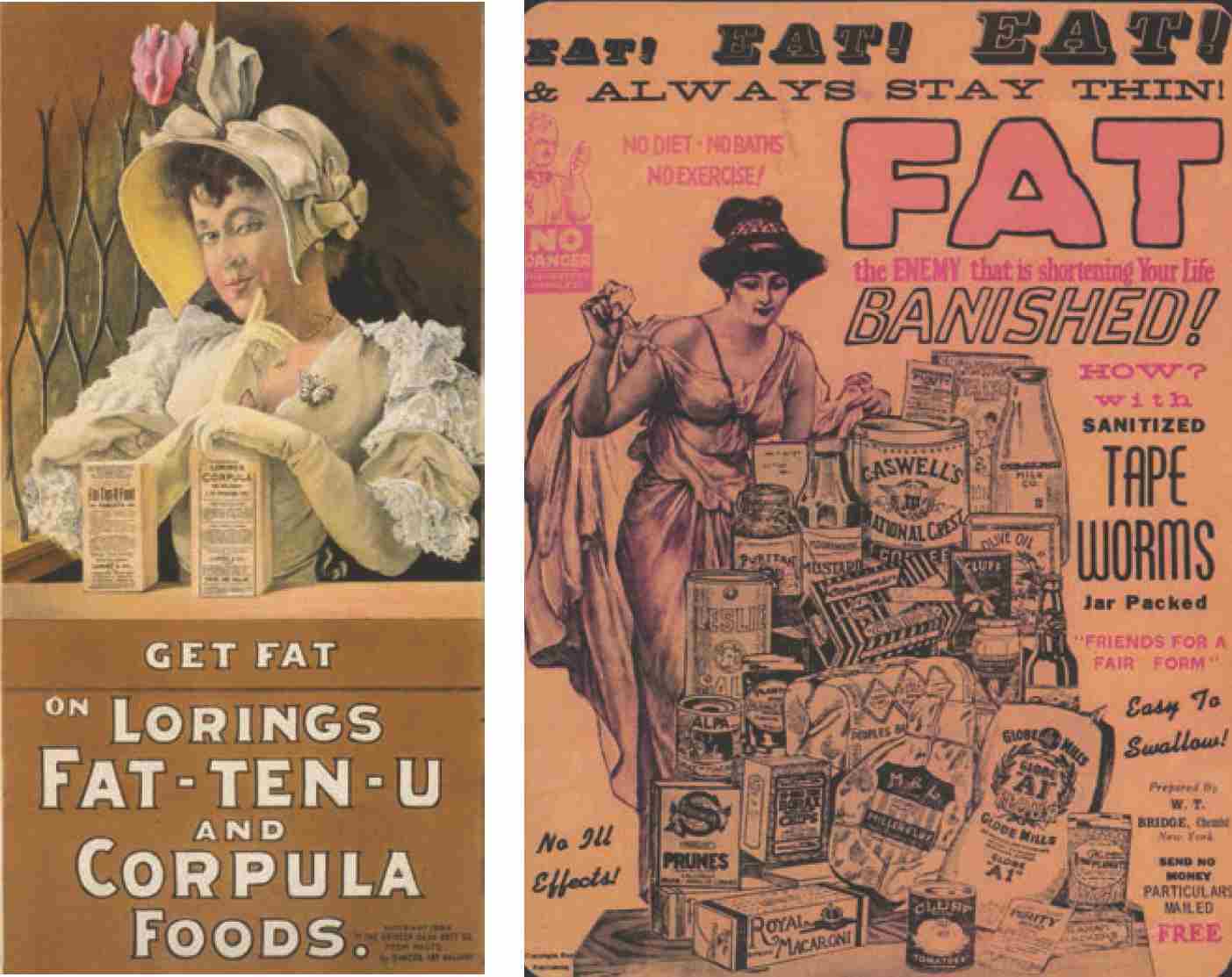

Being fat was considered a sign of good health in the late 1800s. This 1895 ad (left) promoted fat as beautiful. The tablets and packaged food helped put on those attractive pounds.

But in the early twentieth century, being overweight was no longer stylish. The products changed to weight-loss nostrums. This one (right) promoted sanitized, jar-packed tapeworms to banish fat.

Harvey Wiley’s research and speeches focused primarily on food dangers. But as a trained doctor and chemist, he had strong opinions about quack medicines, too.

Newspapers, magazines, and even medical journals carried advertisements for nostrums to treat any ailment. Thousands of pills, syrups, and other remedies were available. Customers could buy them at a drugstore or through the mail, no prescription needed.

Sellers of quack medicines preyed on people with serious diseases, such as tuberculosis and cancer, which had no cures in the early 1900s. The drugs were cheaper than a doctor’s visit, and the advertising made them sound effective and safe.

According to the 1889 advertisement, Dr. D. Jayne’s Tonic Vermifuge cured everything from asthma to worms.

Children often fell ill with potentially fatal illnesses including measles, scarlet fever, and whooping cough. Anxious parents were willing to try any treatment that sounded promising. Fraudsters were glad to provide a tonic, pill, or elixir.

Most of the nostrums didn’t cure or treat any disease. Many were addictive and downright harmful. The labels rarely stated what ingredients the user was swallowing.

“Poor mothers doped their babies into insensibility at night with soothing syrups containing opium or morphine,” Wiley wrote. Some babies became addicted or died. He was frustrated that the public was not more concerned about “these glaring evils.”

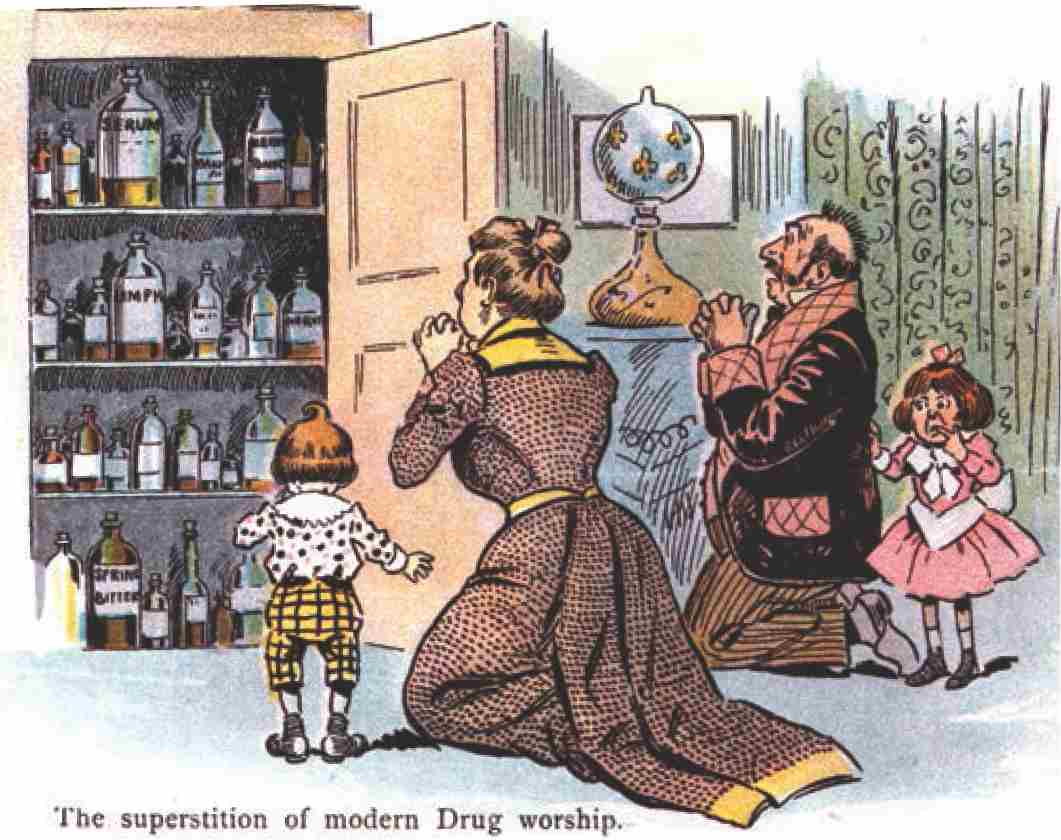

This 1901 Puck magazine cartoon pokes fun at Americans’ belief that proprietary medicines will cure them of every ailment.

Physician and pharmacist organizations, as well as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, urged Congress to add drugs to the proposed pure-food law. Wiley joined the call to require content labels on proprietary medicines. The consumer, he wrote, “should know the exact character of the product he buys.”

Before the Civil War broke out in 1861, sales of proprietary, or patent, medicines in the United States had been $3.5 million. By 1904, the business had exploded by twenty times to more than $70 million. With people buying so many quack medicines, Wiley set up a drug laboratory at the Bureau of Chemistry in 1903. The lab exposed the secret ingredients of numerous nostrums.

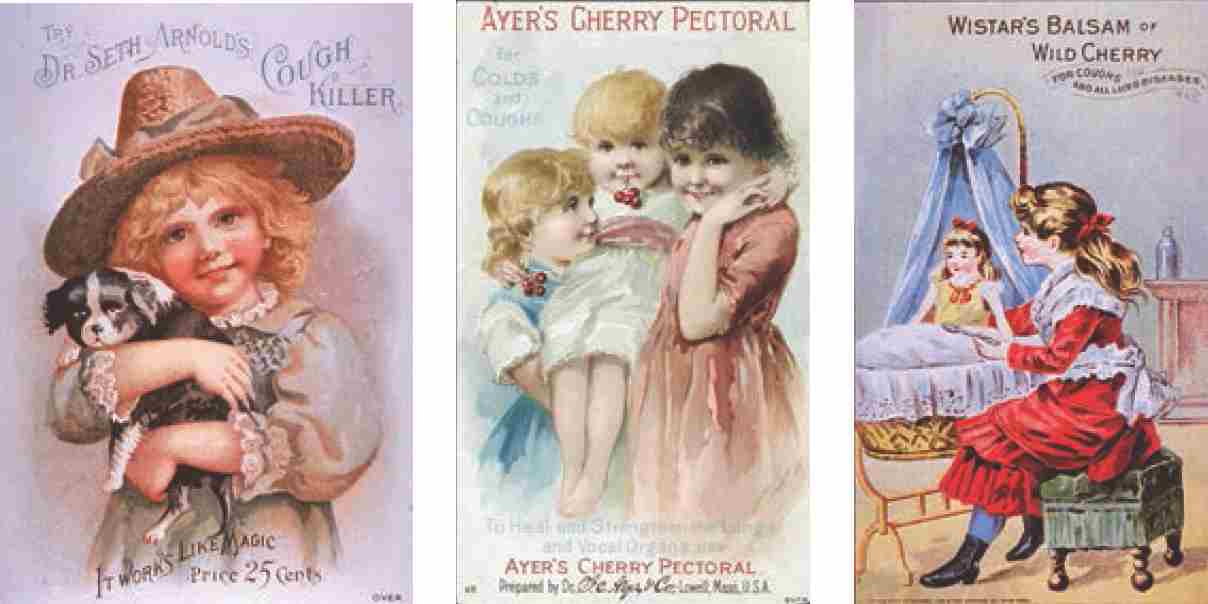

In the 1880s and 1890s, colorful advertisements appeared on posters, in magazines, and on collectible trading cards. To catch the attention of concerned parents, the ads often featured children. This trading card for Dr. Seth Arnold’s Cough Killer doesn’t mention that the medicine contains morphine, a dangerous narcotic. Ayer’s Pectoral (a medicine for respiratory ills) claimed to have been prepared by Dr. Ayer of Lowell, Massachusetts. Attaching a doctor’s name to a quack drug convinced many buyers that it was safe and effective. Wistar’s cough medicine, despite looking safe enough for children, contained alcohol and narcotics.