Three

THE LOSS OF INNOCENCE

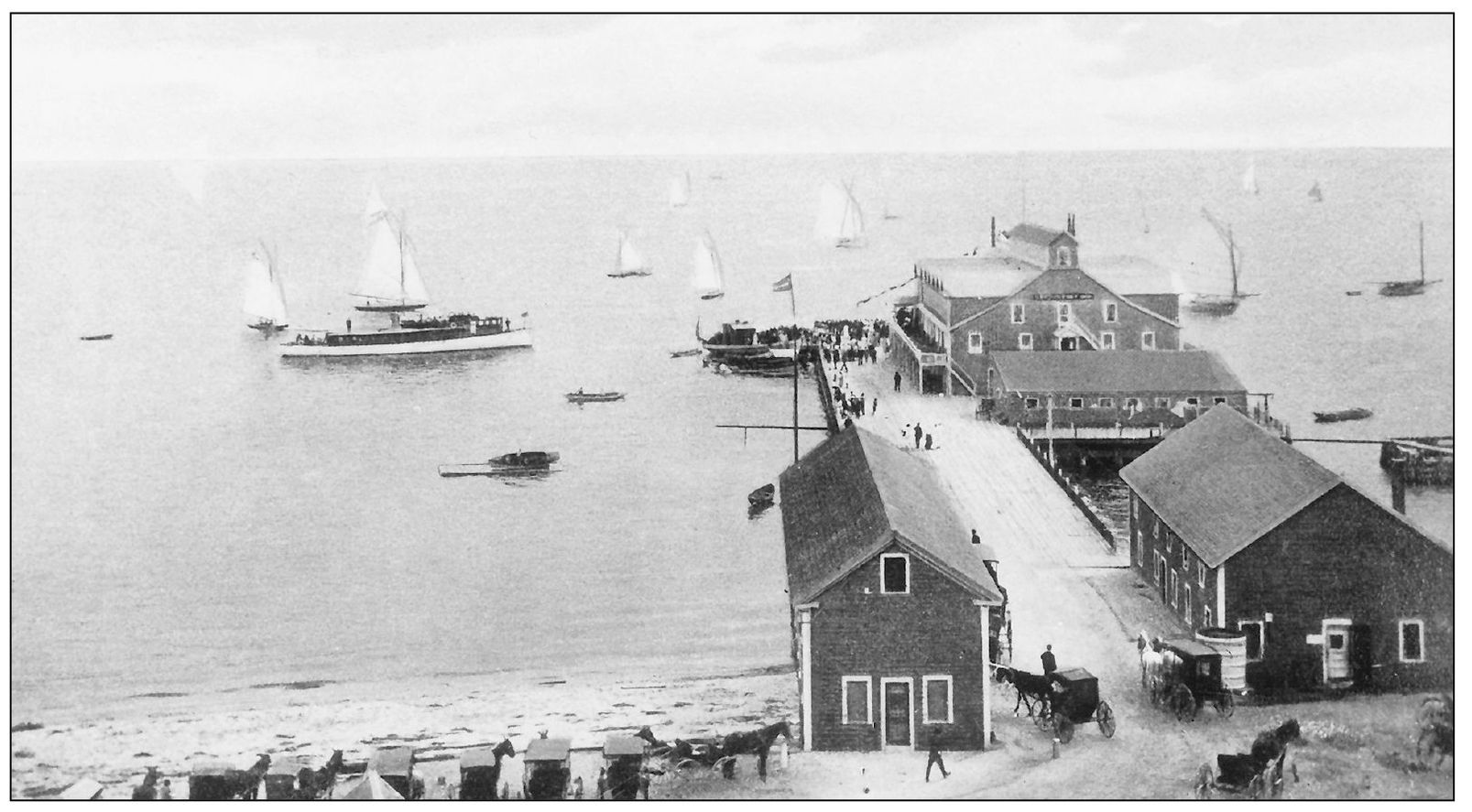

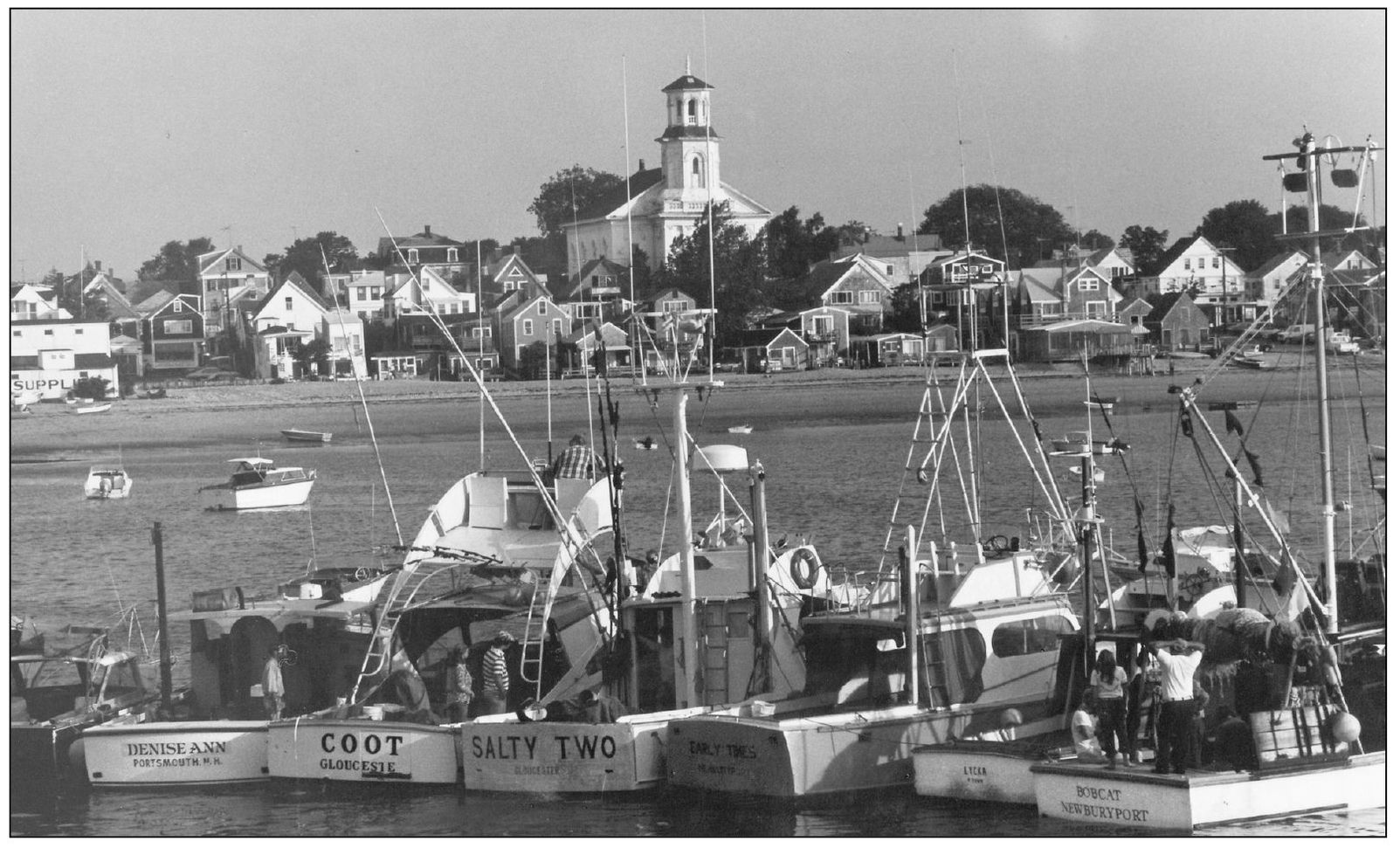

Passion for the romantic narrative of Cape Cod can be traced back at least as far as 1873, when the railroad reached Provincetown. As the country turned from fishing and farming to industry, more families could afford escapes to the sea. The overfishing and deforestation of the first 200 years was followed by the first Resort Era, from the 1870s to the 1930s. Pleasure boats and summer resorts, like the Chequessett Inn (above) at Wellfleet, shared the same shores as the houses and weathered boats of the fishermen.

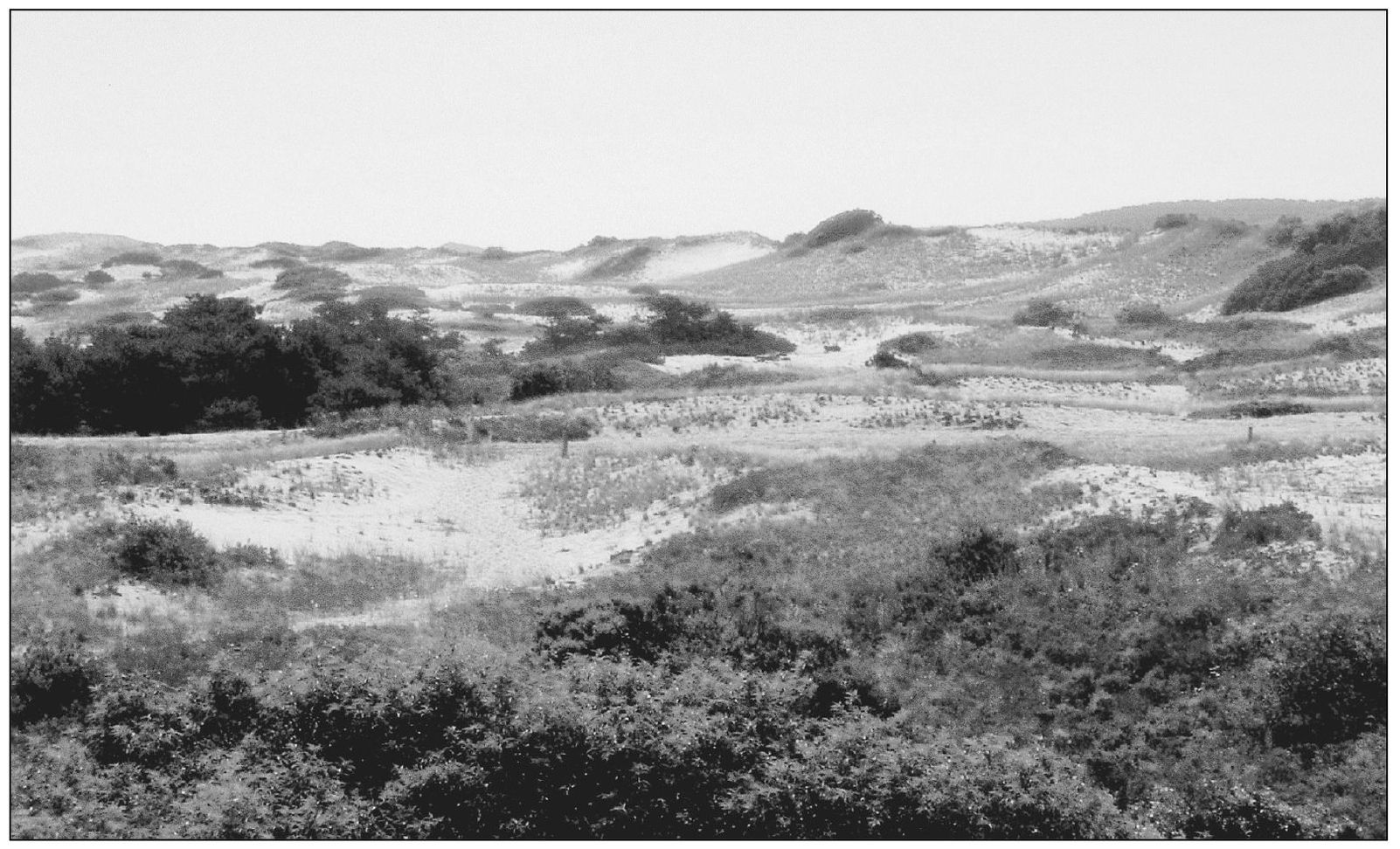

The original pine-oak forests were almost totally gone by the 20th century. European settlers had been cutting forests for fuel and house and boatbuilding from 1650 to 1900. The threat was recognized early. In 1696, the proprietors of what is now Truro ordered “that henceforth there would be no cordwood or timber cut upon any of the common or undivided land.” Such orders barely slowed the destruction. For example, Great Island and the surrounding area had been stripped of wood by 1711.

Fear that sand blowing from deforested Provincetown would fill the harbor there led, in 1714, to the Massachusetts General Court proclaiming “an Act for preserving the Harbor . . . and Regulating the Inhabitants and Sojourners there.” The act created the “Province Lands,” still a protected part of the national seashore. Over the past 100 years, much of the upland forest on the Cape has grown back, especially on national seashore lands, which are protected from housing development.

When the mosquito population threatened the growth of tourism, many of the Cape’s marshes were diked. In 1907, the Boston Herald announced that “Wellfleet, one of the prettiest towns on Cape Cod, is ‘stung.’” Wellfleet’s Herring River was diked to control mosquitoes in 1908. Today the estuary is being restored. Cape Cod National Seashore includes over 2,500 acres of historically diked salt marshes. Work continues to restore these degraded estuaries.

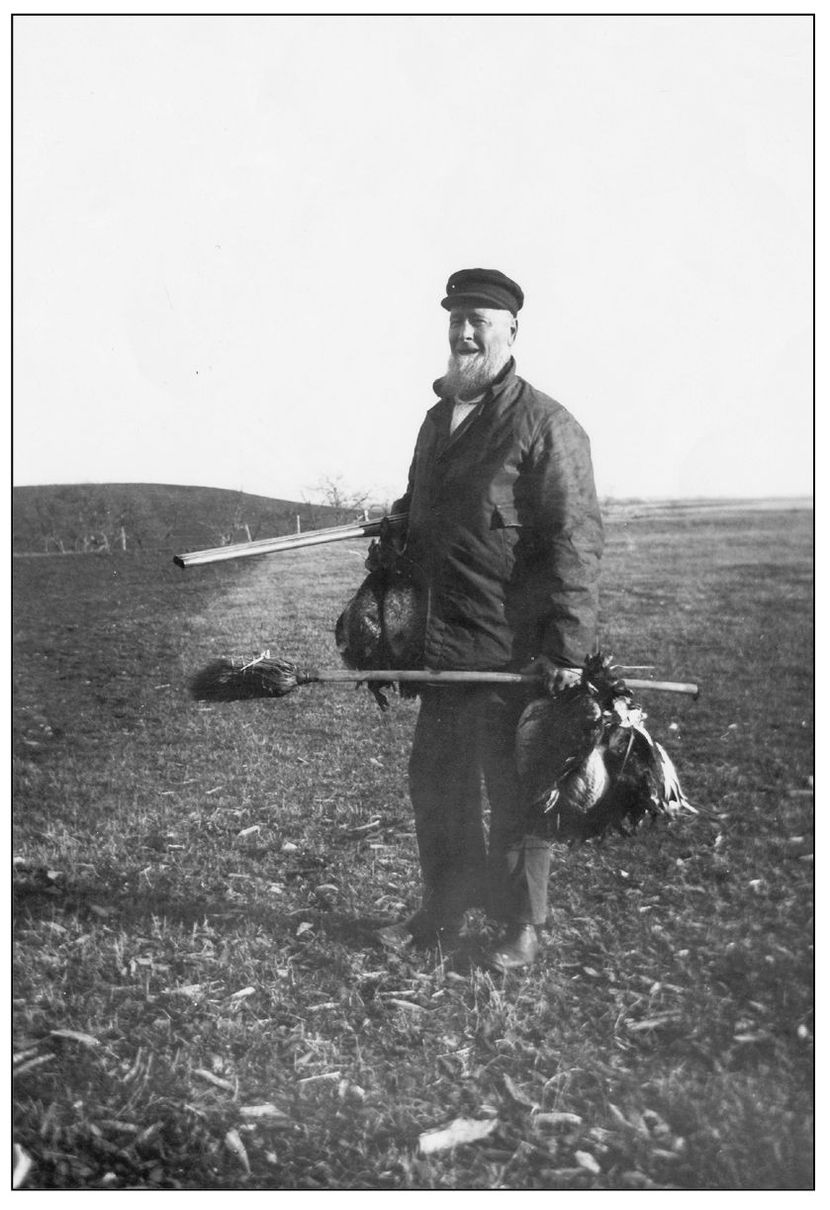

Bird shooting clubs developed along with commercial hunting of waterfowl and shorebirds. One report counted 8,000 golden plovers and curlews shot in one day on the Cape. In addition, the draining of salt marshes took their toll on bird habitats. Both the Federal Migratory Bird Treaties of 1916 and the creation of Cape Cod National Seashore have gone a long way to restore the Cape’s rich bird populations.

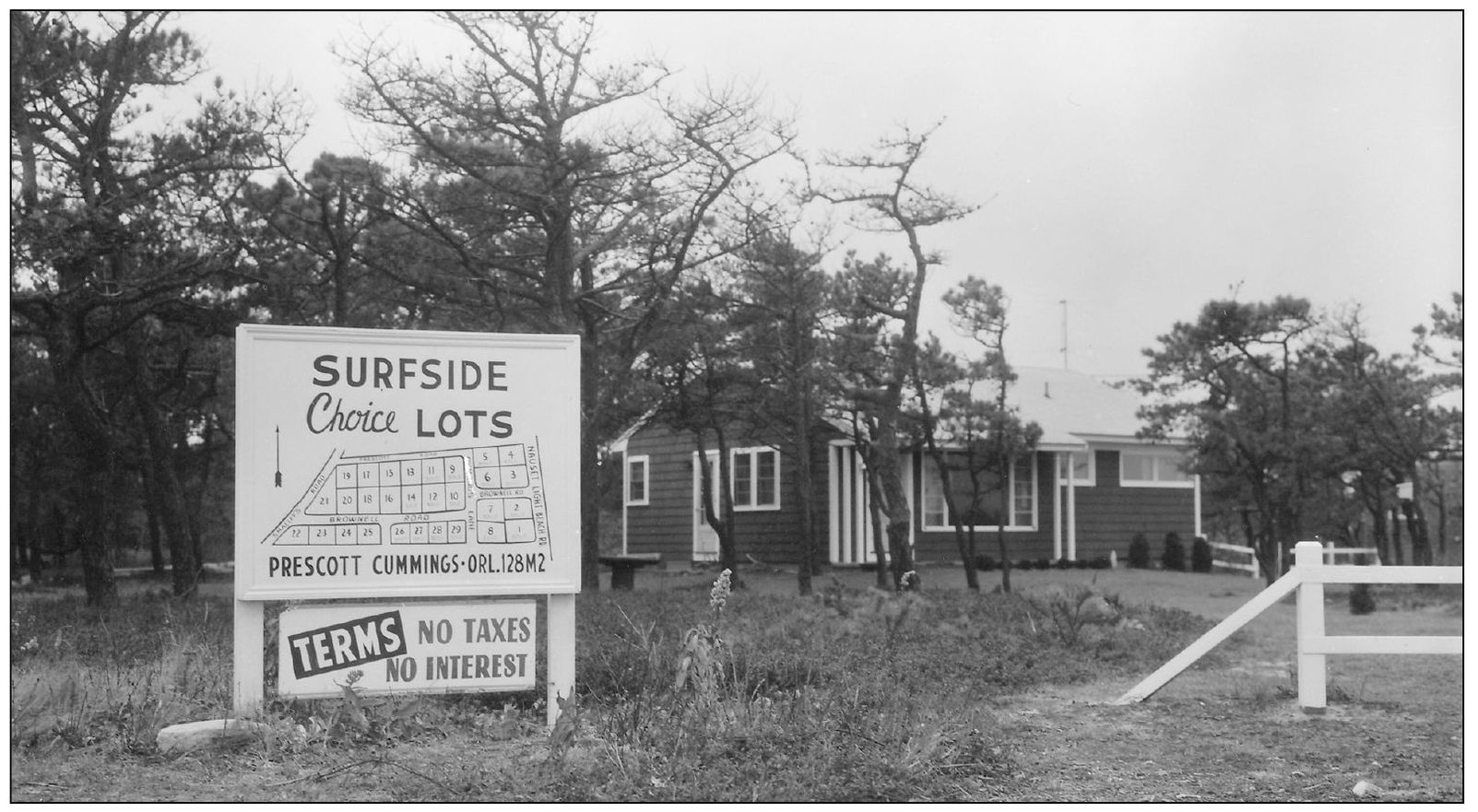

As America prospered after World War II, seaside vacations became within reach of millions. In 1955, the New York Times announced the completion of Route 6: “Speedway to the Tip of Cape Cod—Super Highway Opens Up.” In 1959, the U.S. Department of the Interior published Cape Cod National Seashore: A Proposal. “Without immediate preservation of the Cape’s natural features . . . there is great danger that the . . . qualities which have drawn increasing numbers to the Cape each year will soon be lost for all time, consumed by commercialization and real estate subdivisions.”

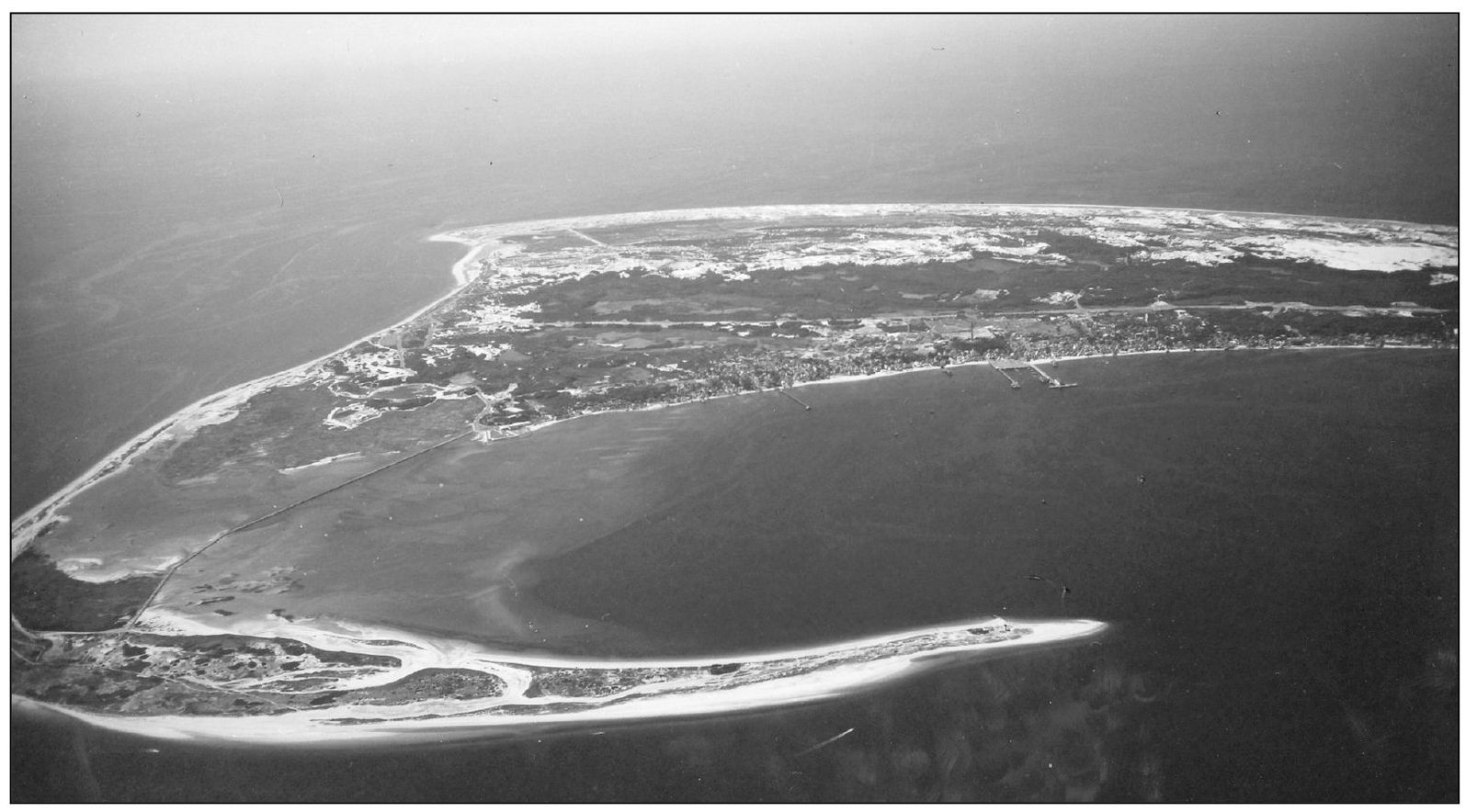

Some Cape Cod towns made detailed plans for expansion. In 1959, Provincetown officials hoped to set aside acreage for development in the West End. Town manager Walter Lawrence organized a master plan for the town. The plan called for filling in marshlands, building a golf course, and high-rise apartments. In opposition, the Emergency Committee for the Province Lands was formed. The proposed master plan never made it to town meeting.

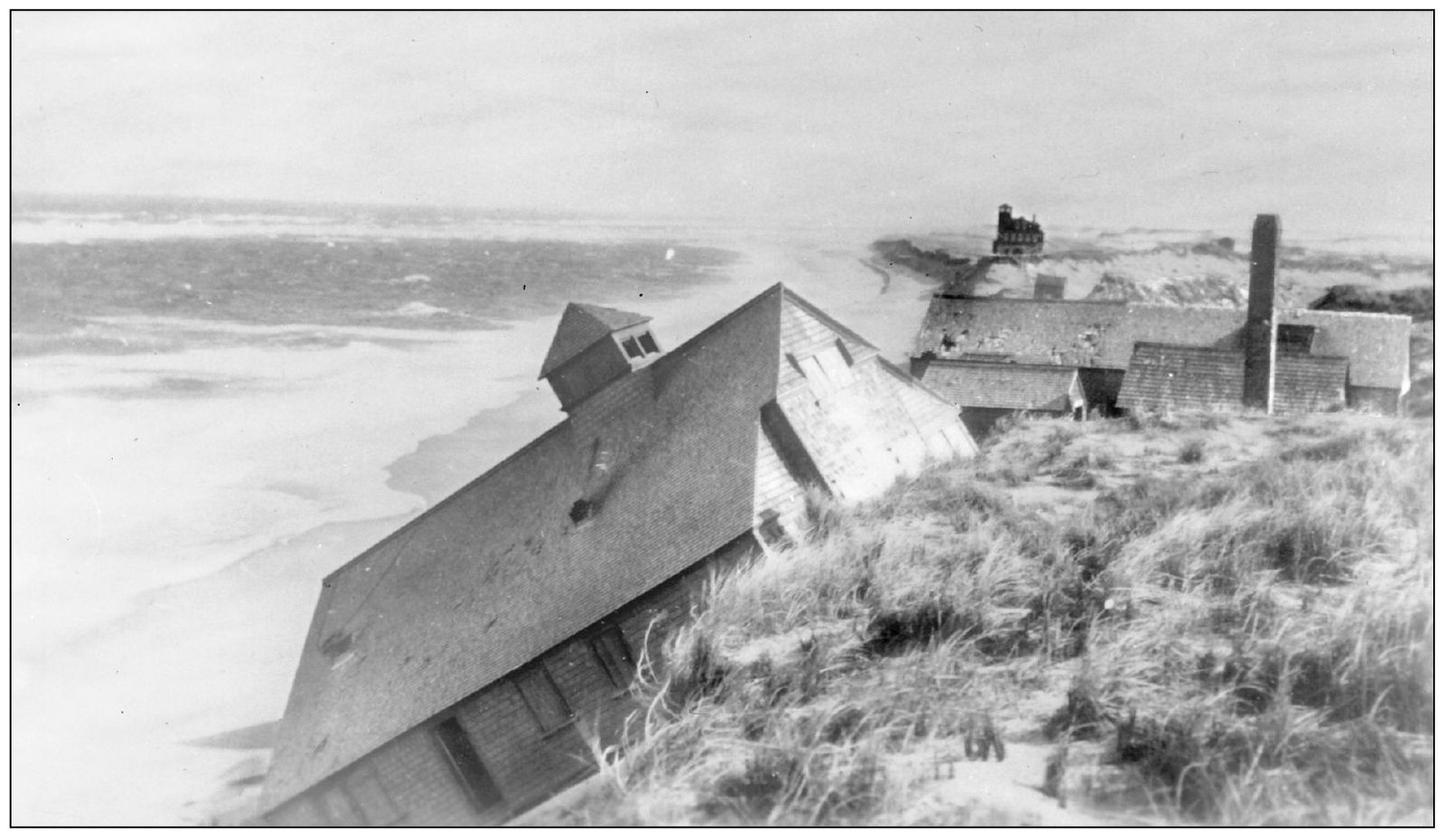

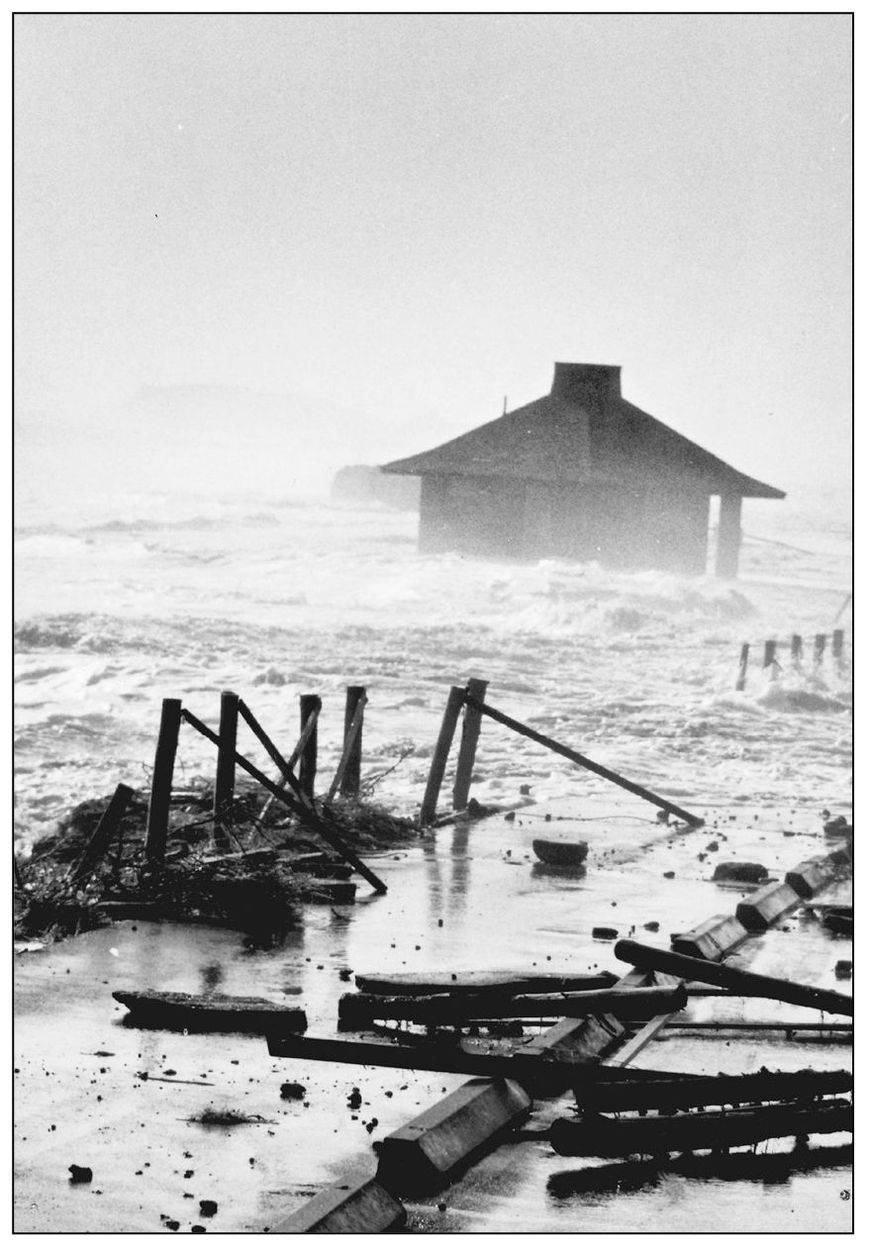

Since the creation of this magnificent peninsula, nature has lashed, blown, and scraped away at it. Major storms can destroy islands (like Wellfleet’s Billingsgate Island) and create or destroy sandbars and dunes. The cape continually changes, despite people’s best efforts to control it. In 1931, a storm weakened the old Peaked Hill Bars Coast Guard Station, where playwright Eugene O’Neill had once lived. The following year the building, pictured above, tumbled into the ocean.

The Great Blizzard of 1978 destroyed both the parking lot and the bathhouse at Coast Guard Beach. On February 6–7, hurricane-force winds and tides 15 feet high slammed Cape Cod. Most of the cottages and 90 percent of the dunes at Coast Guard Beach were washed to sea, and Monomoy Island was severed in two.

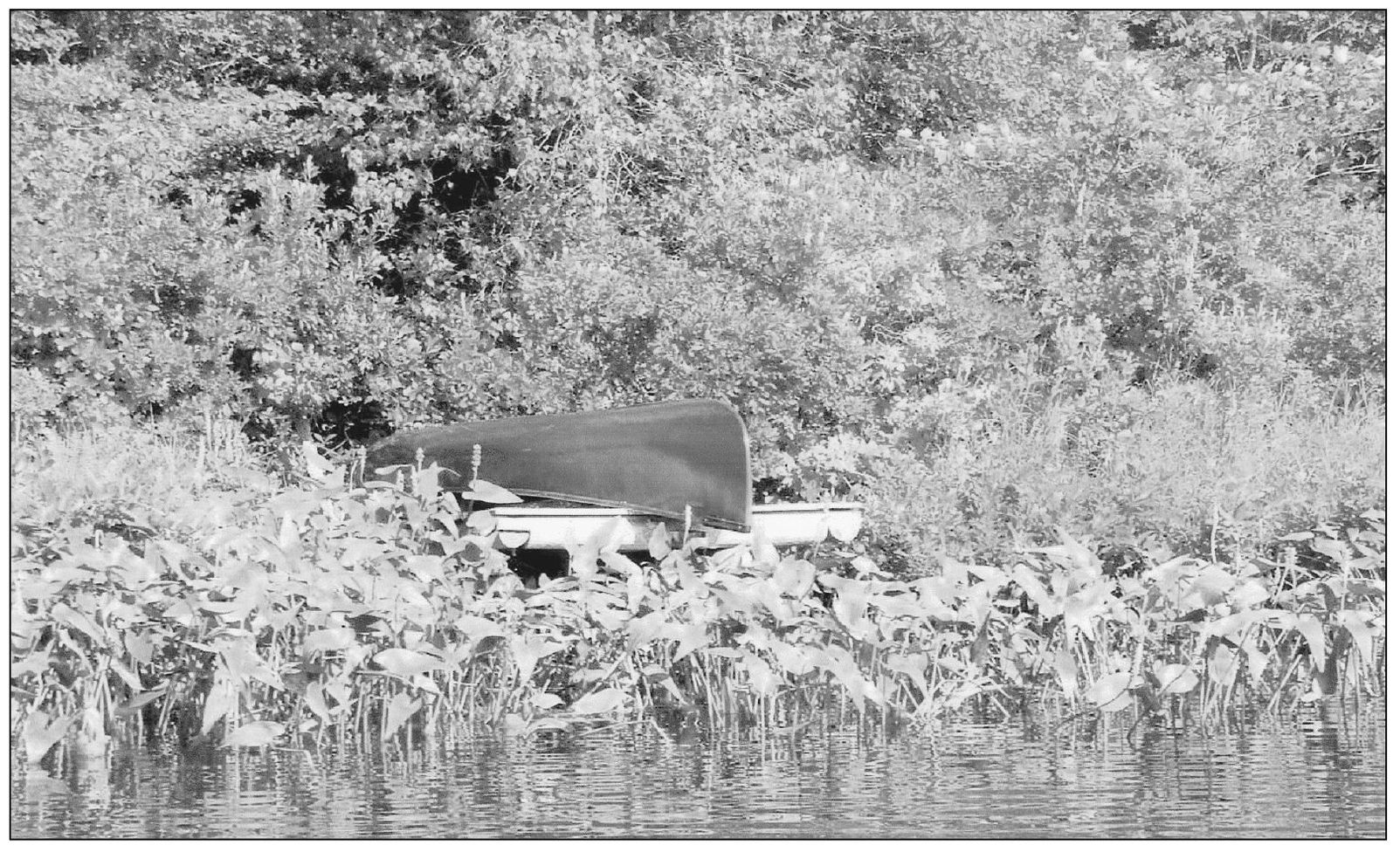

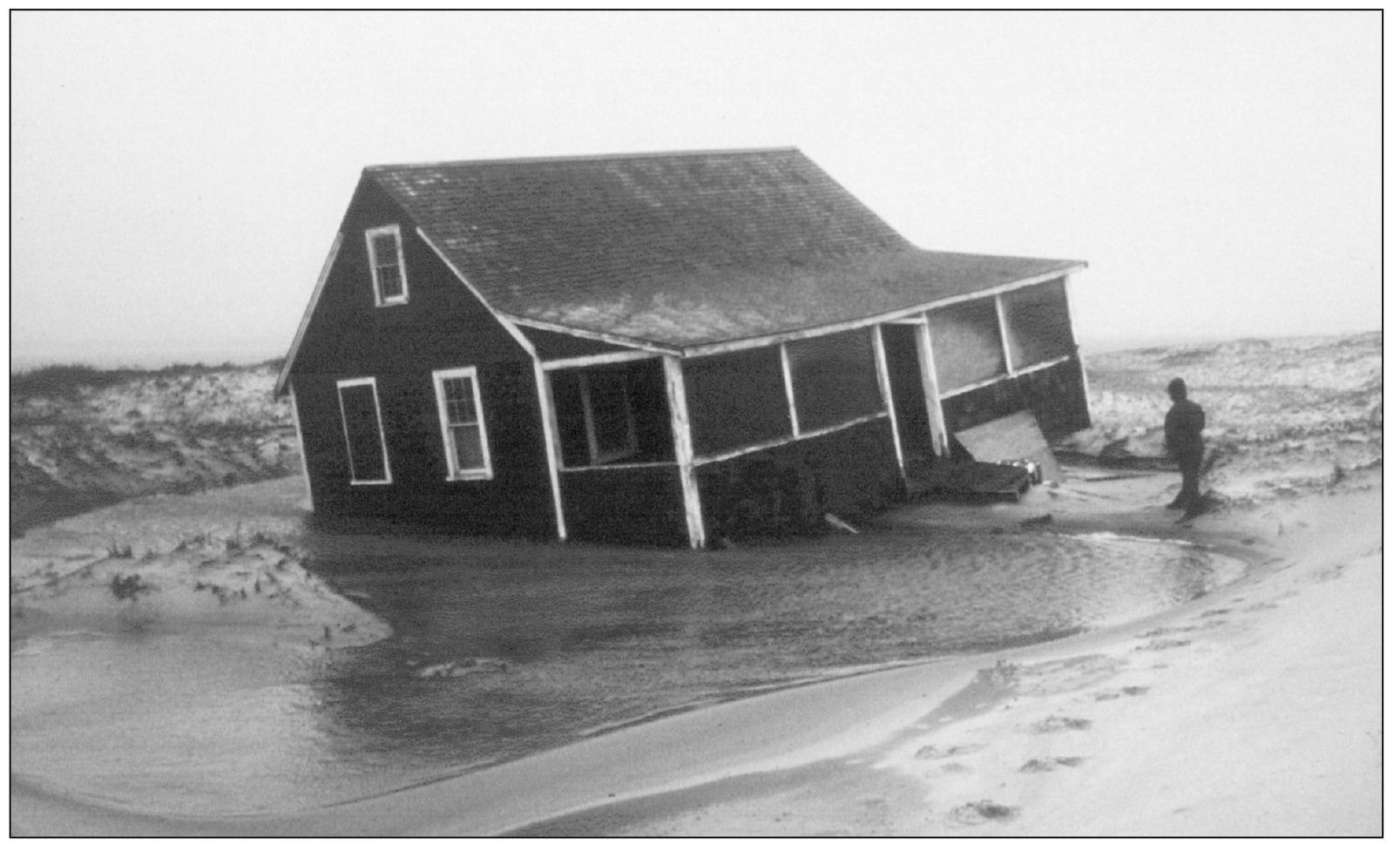

Above is one of the many cottages washed offshore in the blizzard of 1978. Over 10,000 people were evacuated from the New England coast. The five-man crew of a North Shore pilot boat vanished, and the Gloucester boat Can Do lost its navigation equipment in 30-foot waves. The bodies of the crew washed up on the beaches. A Coast Guard helicopter evacuated the 32-man crew of the tanker Global Hope off Salem.

Like this cottage, Henry Beston’s Outermost House was lost in the blizzard. Wallace Bailey, director of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, said of the house, “Strongly built and sturdy to the end, it quit its foundation posts and floated into the marsh. People watching through the fog from Fort Hill could see it, gable-deep but upright in the churning inland sea.”